Alastair: Although most of our posts have been lengthy, our activity here over the summer has been irregular and infrequent. I am hoping we can get back into a better rhythm of regular—and perhaps somewhat shorter posts—over the next few months. However, life continues to be eventful and we have many thoughts we want to share on various topics, so we may not achieve this. Worth a try, though!

While in Stoke-on-Trent, we visit Trentham Gardens very regularly: it is nearby, we are members, and it is a remarkably beautiful place. Trentham, like several parts of Stoke-on-Trent, dates back before the Norman Conquest and is mentioned in the Domesday Book. Originally a royal manor with an attached Augustinian priory, the Trentham Estate was later the site of the grand Trentham Hall. Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, the famous landscape architect, designed the large park that surrounded the Hall. The Hall was so palatial that the Shah of Persia remarked to the then Prince of Wales that it was ‘too grand for a subject,’ suggesting that, when the prince became king, he would have to remove its owner’s head!

During the Victorian era, many hundreds of grand houses were built or expanded in the British countryside, as fortunes were made through industry and empire. These houses were typically surrounded with many acres of land worked by tenant farmers; with the various estate-workers, the farming of the lands of such estates and the upkeep and service of their palatial houses could provide employment for large communities. Trentham Hall was built for the Duke of Sutherland, then Britain’s largest landowner.

From the end of the nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century, the great estates came under rising financial, social, and political pressures that led to their general collapse and the sale or demolition of many of the great houses. The old palatial properties and the social order they represented simply no longer sustainable. After the First World War, a land price boom led many landowners to sell off large amounts of their land, to former tenants and others. In the new order that was emerging, the squire no longer enjoyed the same centrality in the rural economy and the skilled workers and servants who would formerly have found work on the estates were drawn into more lucrative and freer forms of employment. The cost of domestic staff increased to the point that the old country houses could only be sustained by the exceedingly rich. The disruption caused by two world wars, during which great houses were sometimes requisitioned by the government and many of the menfolk of both the families of the owners and their staff were killed was also considerable. The extension of the franchise had diminished the extensive political power formerly enjoyed by the nobility and public opinion was not favourable to the interests of the landed aristocracy.

So-called ‘death duties’, an inheritance tax initially set at 8% on estates of over £1 million in value in 1894, climbed to 40% on estates of over £2 million in 1919, and eventually hit a ruinous 65% in 1940. The upheaval was immense: vast amounts of land changed hands (the scale of this is only comparable to that following the dissolution of the monasteries), over one thousand great houses were demolished (in 1955, one such house was demolished every five days), and almost all that remained were greatly diminished from their former splendour, selling off much of their land, art, demolishing parts of their properties, passing ownership to the National Trust, or surrendering them to dereliction.

It was not really until the 1970s that public opinion and the law finally staunched the destruction of the old estates and started to reverse the situation as their value as national heritage sites came to be appreciated. This was too late for Trentham Hall, however, which had been one of the earliest and most notable victims in 1912-13. The Duke of Sutherland no longer used the house as a residence, partly because the River Trent that ran through the estate was so badly polluted. The pollution and the large maintenance costs of the Hall discouraged both Staffordshire County Council and the newly-formed Stoke-on-Trent Corporation from accepting the Duke’s offer of the property, leading him to demolish it.

Over the last couple of decades, the Trentham Estate has become something of a destination, with the UK’s largest garden centre, a classy shopping village, and its renowned Gardens. In all the time we have been together in Stoke, however, I had never taken Susannah to Trentham Monkey Forest, which covers a sizeable part of the estate. Two weeks ago, while wandering through Trentham Gardens, I finally persuaded an initially resistant Susannah that we should visit it. Stoke-on-Trent is perhaps the place you would least expect to encounter a colony of one hundred and forty Barbary macaques roaming wild through Capability Brown landscaped woods, but it is a city full of surprises!

There is a central clearing, where the macaques are generally fed, surrounded by beautiful woodland, through which there are a few footpaths. The entire Monkey Forest is surrounded by a high fence; within it the macaques live much as they would in the wild. In the central clearing, there were several keepers, who gave us an introductory talk and answered lots of our questions. As they explained all the complicated relational dynamics, the Monkey Forest sounded like a soap opera with numerous complex subplots. For instance, after two high-ranking females had fallen out, the group had split into two, with a splinter group moving deeper into the woods.

There were several baby macaques in the Monkey Forest, of which we saw a couple. One was especially adorable, climbing around on the backs of various of the adults of the colony and generally being a handful. It had been over a decade since I last visited the Monkey Forest, but we now have an annual membership, so will almost certainly return regularly over the year.

In my final news update in our previous Substack I mentioned that we had some friends visiting from New York. They were exploring the North East of England for most of the week, but stayed overnight with us on the Thursday and Friday evenings. Over the times they were with us, we were able to introduce them to Staffordshire oatcakes and to a little of our local area.

The Saturday before last, Susannah and I travelled down to London. The plan was to meet up with our friends at church on Sunday morning and then explore and enjoy London with them until Tuesday morning. Susannah and I both had work that we needed to do, so we did that for a few hours in a café, before going on to Churchill’s War Rooms, which neither of us had visited before.

Churchill’s War Rooms (now one of the Imperial War Museums) were set up underground beneath the Treasury building in Whitehall just before the outbreak of the Second World War. It is a warren of corridors and small rooms, which housed, among other things, a wartime government command centre, with a cabinet room for government meetings, BBC broadcasting room, switchboard room, a map room for strategic planning, a top-top secret telephone room, with a door disguised as that of a WC, fitted out with a special encrypted telephone line called SIGSALY, which Churchill used exclusively to communicate with FDR, and bedrooms for Churchill and other key staff. The War Rooms now also contain a modern museum dedicated to the life of Winston Churchill.

After a few hours exploring the War Rooms, we went to the friends with whom we were staying that evening. They prepared the most incredible meal for us and we enjoyed a few hours of stimulating theological conversation!

The next morning Susannah and I went to Emmanuel North London Church, which is always a delight to visit. After their morning service—and a superb sermon from Steve Hayhow on Acts 19 and the riot in Ephesus—they have a coffee time, followed by smaller group discussions of themes from the sermon in a forum, and then they eat a meal together. The church is extremely friendly and the organization of their meeting, with the extensive time of fellowship afterwards, allows for very natural conversations about themes arising from the sermon to continue for over an hour, without it being overly weighted towards speech from the front.

After church, where we met up with our friends again, we went to the British Museum. Several of the exhibits we had hoped to show our friends were temporarily closed—most particularly the Assyria exhibits and the Elgin Marbles. However, the British Museum has the largest collection of any museum in the world, so there was little chance of us being without things to see!

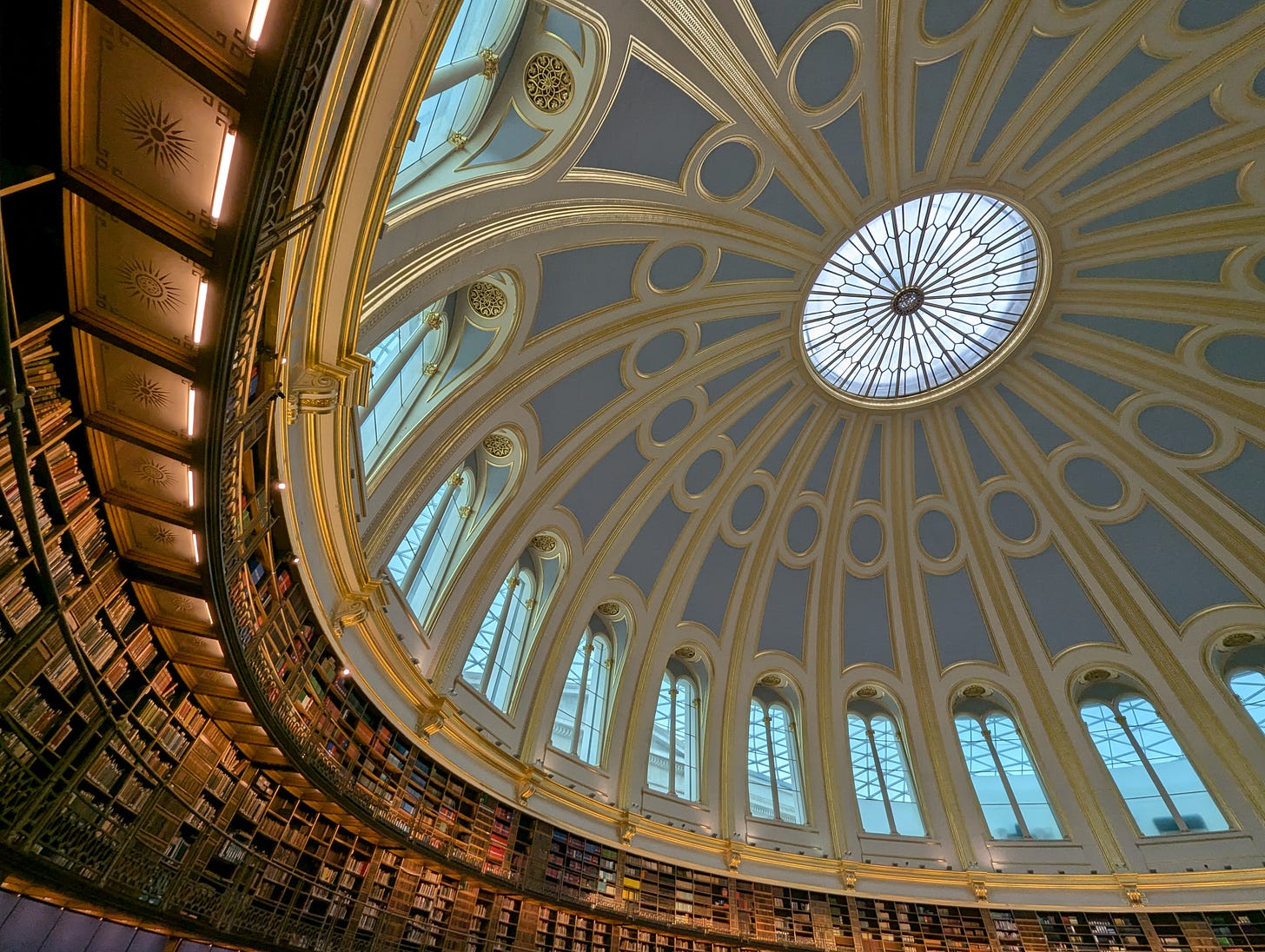

I was especially keen to see the recently reopened Reading Room, which I had not seen before. As our route to the Assyria exhibit took us by it, we went there first. The Reading Room, in the centre of the Great Court of the Museum, has a glorious domed roof, inspired by the Parthenon in Rome, of over forty metres in diameter. The Reading Room has been used by a who’s who of famous—and infamous—figures: Gandhi, Marx, Wilde, Orwell, Lenin, Conan Doyle, Twain, Kipling, and countless others. It is no longer the main reading room of the British Library, which moved to a location in St. Pancras in 1997.

After seeing the Reading Room, we went on a whistlestop tour of the Museum, taking in many key sights in Egypt, Greece, Rome, and early Britain exhibits, before it closed.

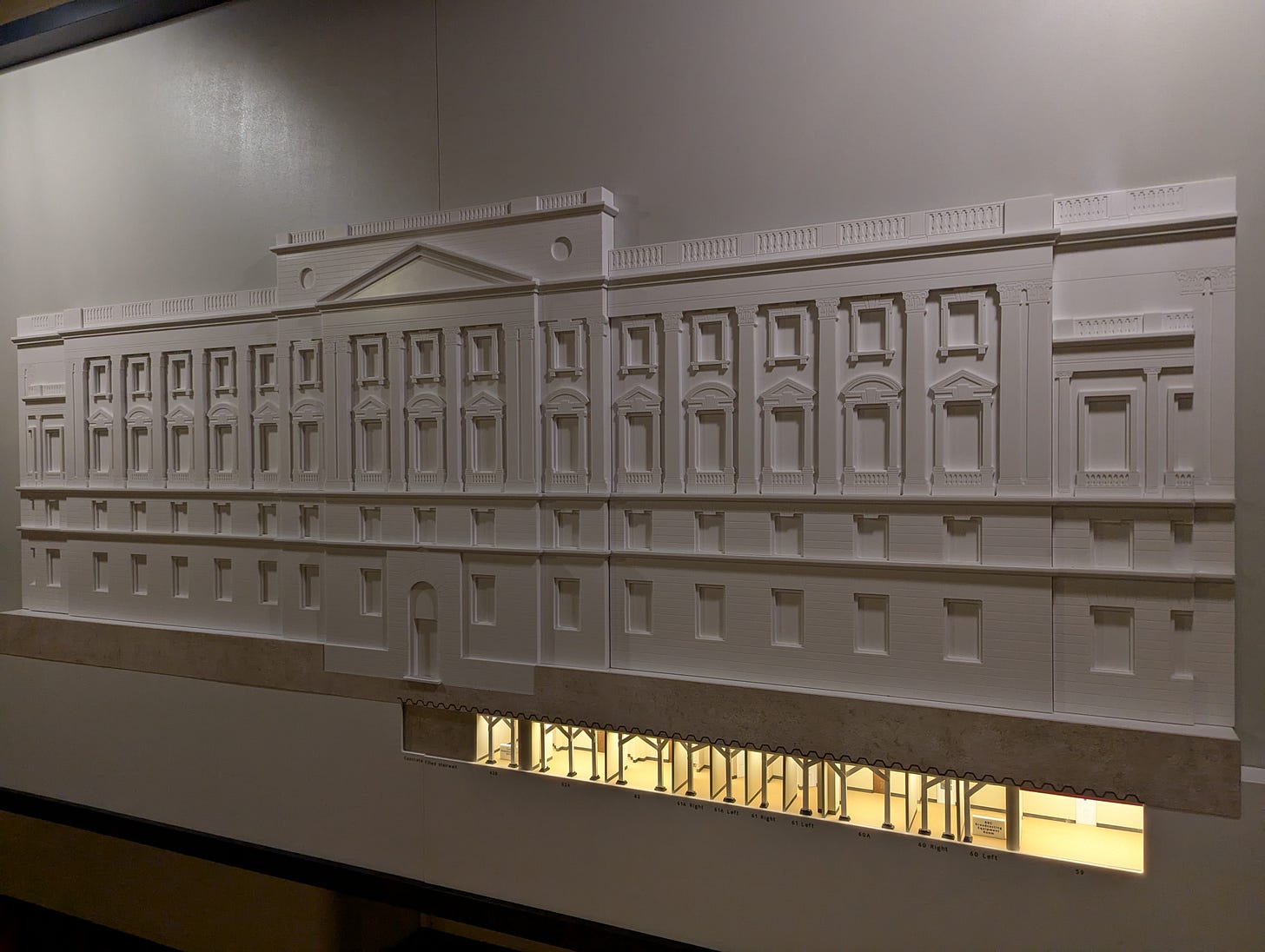

From the Museum, we walked around London, briefly showing our friends Fortnum and Mason, before going to Buckingham Palace.

We ended the evening with a pleasant pub meal near our AirBnb accommodation.

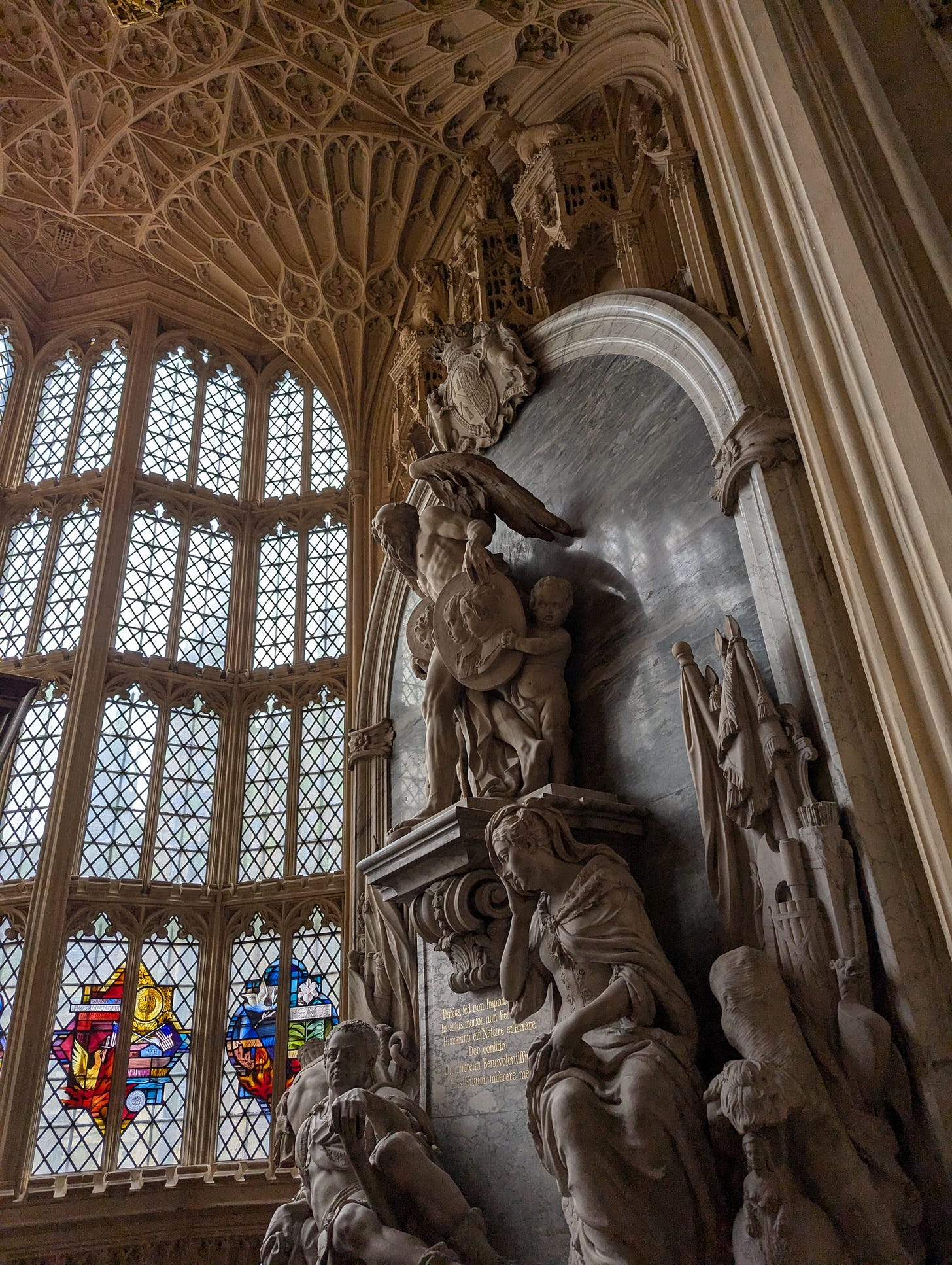

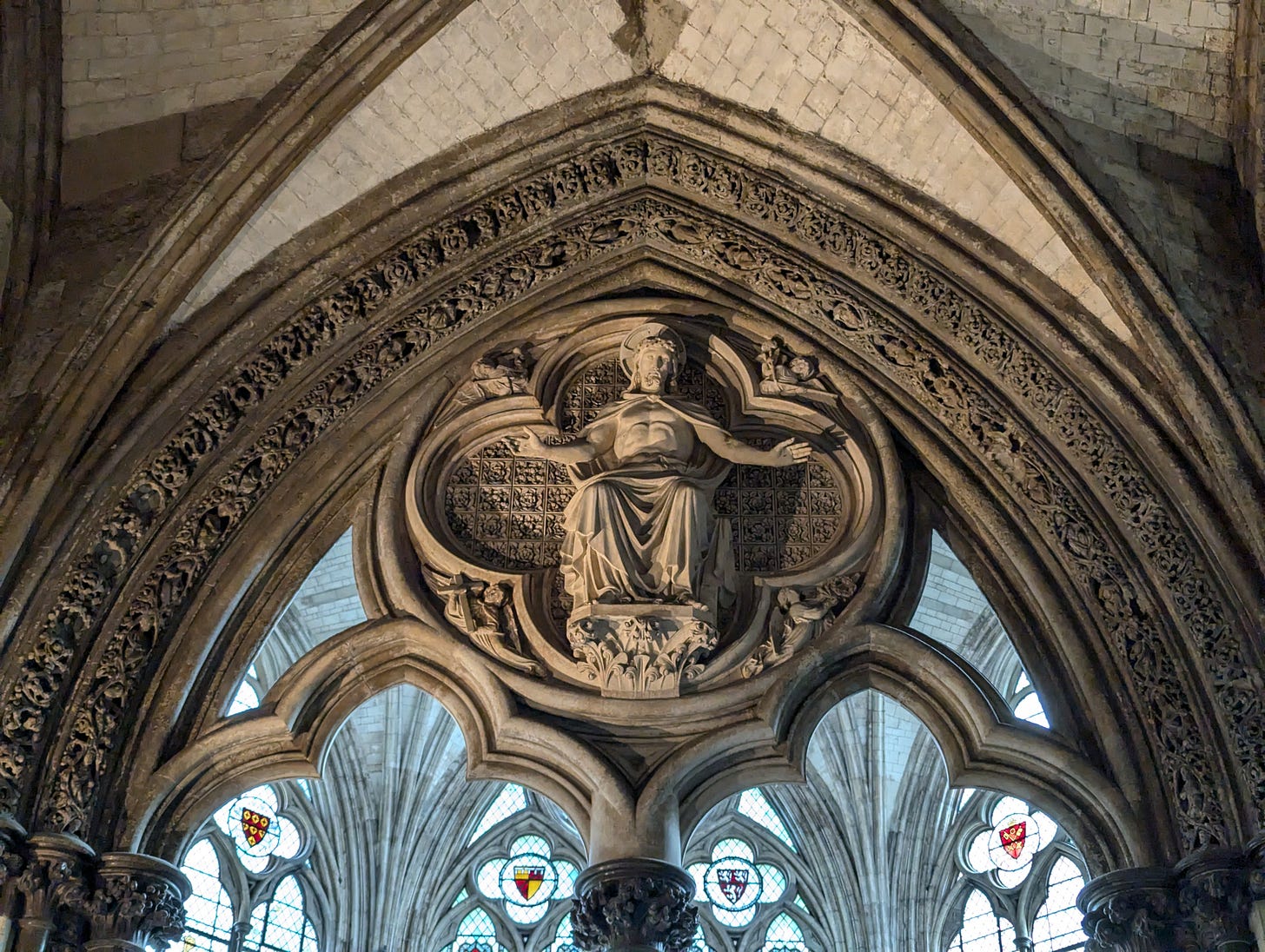

The next morning we began the day with a full English breakfast, our friends’ first experience of such a breakfast. While Susannah got some work done, the rest of us spent the morning exploring Westminster Abbey.

I have written at length about Westminster Abbey on this Substack before. The building is magnificent and overwhelming; there are also few buildings that make me think as much as it does. Besides its arresting splendour, it is a sort of political theology in stone and raises countless challenging and thought-provoking questions about the relationship between Christian faith and national identity and history.

We had about three hours to spend there, but ended up moving faster than I had expected, as there was simply so much to see. I had not seen the gardens of the Abbey before, for instance, so we spent a short time there.

From the Abbey we went to a hotel, where we had booked afternoon tea. We wanted our friends to experience some true British cultural and culinary experiences and, partly due to Susannah’s firm resistance to the idea of eating jellied eels again, we decided to treat them to an afternoon tea. We had shared such a tea earlier in our relationship, so the place held very fond memories for us.

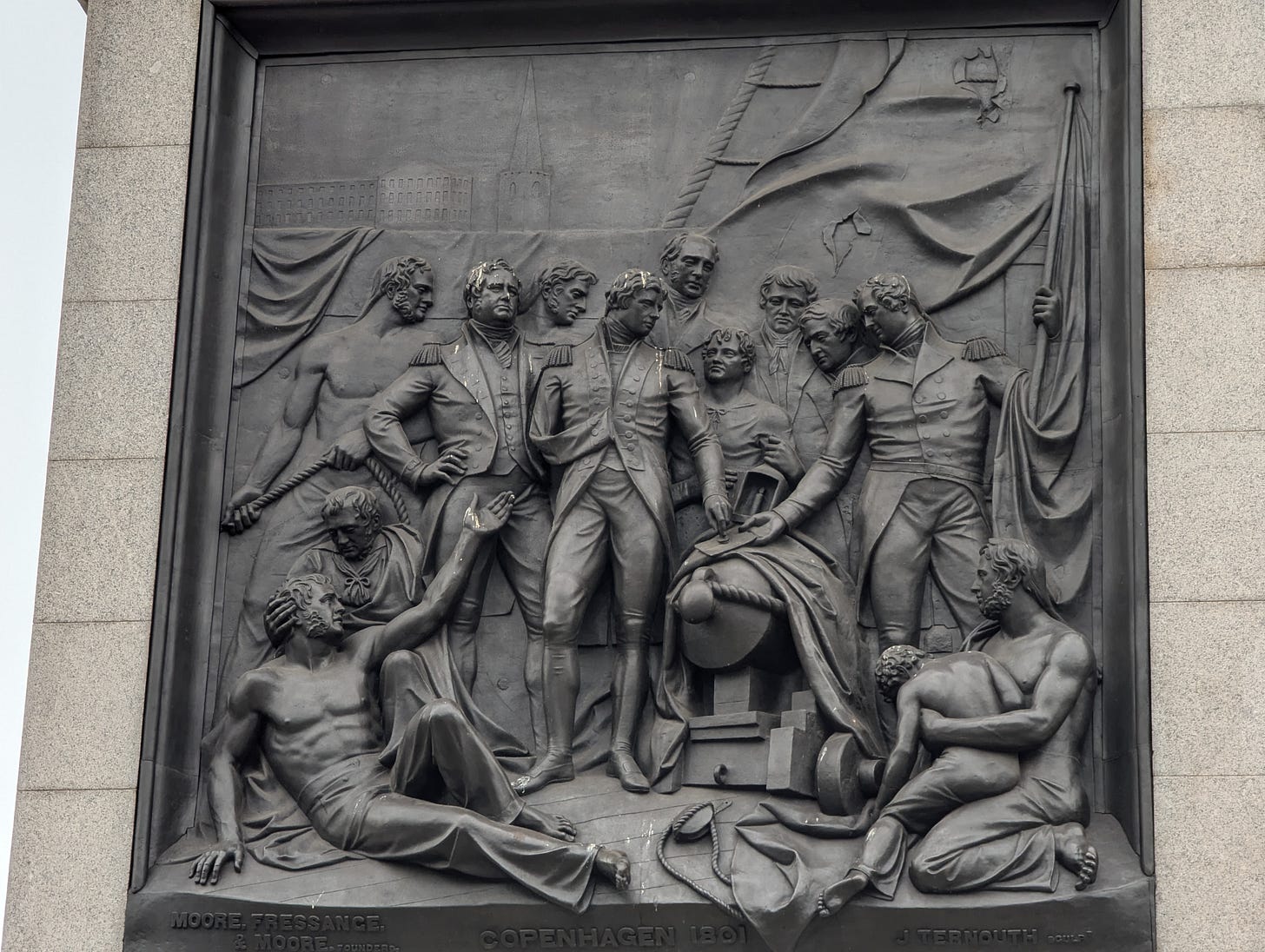

Susannah, as anyone who follows this Substack should know, is an avid sailor. Knowing her love of sailing and of tall ships, I have kept an eye out for opportunities to see tall ships. Recently a news item came up in one of my feeds, mentioning a replica late sixteenth century Spanish galleon, the Andalucía, visiting London. I was especially excited to hear that the galleon would be passing through Tower Bridge. [Susannah: I would call this burying the lede. It was an absolutely incredible sight]/ The fact that the galleon’s visit coincided with our London trip was a wonderful surprise, so our plan was to go from our afternoon tea to see the galleon pass through the bridge at 4pm. However, reports of the time the galleon was arriving were mixed and it was not in fact coming until 5:30pm. We wandered across Tower Bridge, by the Tower of London, and worked in a Starbucks until the time it was due to arrive.

About five minutes before the galleon was due to pass through, the bridge started to raise. People were gathered along the sides of the Thames to watch. I had found the stump of a tree, situated a little way back from the railings; standing upon it, I was afforded a wonderful unobstructed view.

Seeing the galleon pass through the bridge was truly exhilarating. The thrill of excitement in the crowd, witnessing such a vessel and such a moment, was palpable. Having passed through, it turned around in front of us before passing back through the bridge again, a half hour later. It was then brought into St Katherine’s Dock, where it was moored.

From the galleon, we walked along the river to the Globe Theatre, where our friends were going to see a performance of The Taming of the Shrew. Susannah and I went back to our accommodation and watched Kiss Me, Kate together.

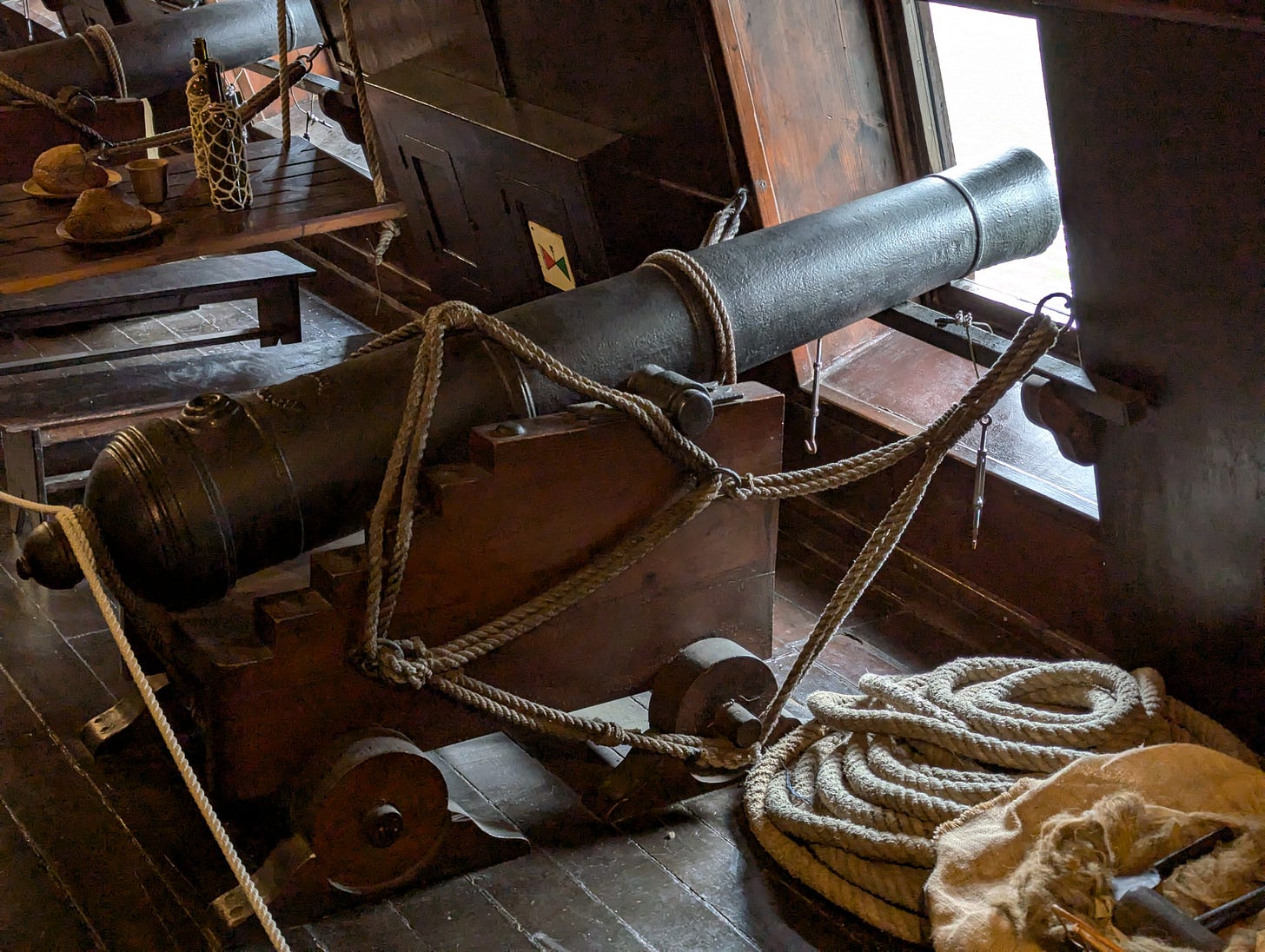

Hearing that the galleon was visiting London, I had booked tickets to see on board the vessel at the first opportunity and a while in advance. The galleon opened to visitors at a delayed 10:30am on Tuesday. There were several visitors alongside us, but we were surprised by how few there were. Hearing from visitors who went later in the week, they described it being packed. The people running the galleon had not expected such interest to build, but several news outlets reported its visit (and I had over eleven million impressions on a post sharing a video of it online!). [Susannah: he also became briefly very popular with Spanish Nerd Trad Twitter, members of which kept reposting the video with a meme of Philip II grinning and text implying that Spain had been playing the long game.]

The galleon is a stunning reconstruction and can sail or operate with an engine. Much of the area below decks has been converted to serve as a museum of life onboard such a vessel. Considering the historical importance of such vessels, especially in the Spanish Armada, certainly added to the experience. I found myself wondering just how greatly history would have changed had the Armada succeeded. The galleon will be in London until October the 6th.

From the galleon we made our way back to Liverpool Street to see our friends off to the airport. We then made our way back to Stoke-on-Trent.

The week since our return from London has been relatively quiet and pleasantly routine. I have taught several hours of classes, recorded a few podcasts, had a number of meetings, prepared and preached a sermon, wrote a couple of articles, read a few books, and lots of other usual things. My parents also joined us for a meal on Sunday.

On Wednesday, we joined my parents to visit the Brampton Museum, a museum in Newcastle-under-Lyme, very near to us (Newcastle-under-Lyme is a market town adjacent to Stoke-on-Trent, within easy walking distance of our house). Despite being in Stoke for much of my life, I had never visited the museum.

We were blessed with beautiful weather and spent a few minutes exploring the sensory garden next to the museum. They also had the base of some old pottery kilns on the site.

The museum, though small, is quite impressive. On the ground floor they had several rooms with objects of local interest, including a large model of the centre of the town in pottery. They also had reconstructions of old family rooms.

Upstairs, however, was the highlight. From a room filled with childhood books and toys of various periods, you move into an area with a series of dark narrow passageways between Victorian shop windows, through which you can peer into bright rooms filled with fascinating displays of items from the period. There is a chemist, a doctor’s surgery, a general store, among others. For a local museum I had never heard of, it truly was a surprise.

Outside they had an aviary, and some war memorial statues. After looking around outside, we joined my parents for a meal in their apartment.

Susannah is about to return to the US and we will be apart for around a month and a half; it is the longest that we have been away from each other so far, as I have events coming up in the UK and will also be in France to celebrate my brother’s fortieth birthday, Susannah has a family event in the US, and flights are too expensive for her to travel back for a relatively short period.

As Thursday was our last full day together, we decided to take two hours out in the early afternoon. It had been over two decades since I last visited Ford Green Hall, a nearby timber-framed farmhouse. This year is the four hundredth anniversary of its construction. As it would not take long to visit, and we knew we would be pressed for time, we thought we would make a brief trip there with a friend.

Ford Green Hall (you can see a virtual tour here) may be of modest size relative to other buildings of the period in our area—it is much smaller than Little Moreton Hall, for instance—yet it is a wonderful and eccentric building. There was a welcoming atmosphere and the house seemed to be well set up for younger visitors too.

Downstairs there is a main hall, a parlour, and a kitchen, among other rooms (one of which now houses a small tea room and shop).

Upstairs there are bedrooms, with various displays within them.

Behind the house is a small herb garden, delightfully divided into sections labeled ‘magical’, ‘medicinal’, ‘domestic’, ‘textile’, ‘culinary’, and ‘cosmetic’. To the side of the house is a dovecote. We ended our visit to the house with a drink in the tea room.

Beyond the property is a small nature reserve, which, after walking around the outside of the house once more, we wandered into, walking around the lake before catching an Uber home.

On Friday morning, I saw Susannah off at Stoke station. It will be a long month or so before we next see each other!

Walking

Susannah: I write on the plane, heading back to New York, but I’m already missing Stoke. The latest innovation in the West Midlands lifestyle is something I truly was not aware of, but it’s been a revelation. Here’s what I’ve found out: It turns out that if you put on some comfortable shoes and open your front door and walk outside and then keep walking in most directions, you will eventually get to what I can only describe as “countryside.” Green parts, with paths through them, fences, stiles to climb over, hills to climb up. Often there are cows or horses or sheep, and if you use your eyes you can see blackberries in the hedgerows absolutely everywhere, and you may see a fox.

Anyway I know that’s probably not news to most of you but let me tell you to me it was a revelation. There’s so MUCH of it! And it’s green, and pleasant! Except when it’s raining, which is frequently but not as frequently as one might fear.

All my life I’ve had people tell me “Oh I couldn’t possibly live in New York City, I need to be able to get out into Nature.” This has always baffled me: why? Of course Nature is a nice place to visit, but you wouldn’t want to live there. Plus it’s quite vague and hard to picture: are we talking mountains? Jungle exploration? Something about tide pools? I do love a good tide pool. Isn’t Central Park nature?

I’m still, I must admit, confused on the “Nature” front. But “Countryside” is something different. I feel like it may be possible that we simply don’t have a similar phenomenon in the US: we have plenty of woods, and national parks, and people’s land, but you can’t walk on other people’s land, and hiking in a national or state park, or walking down a random road in Upstate New York or New England, isn’t quite the same thing. In the UK—and apparently much more so in Scotland—they have what are called Rambler’s Rights, which means something like (am unclear on this) you can just leg it across other people’s fields as long as you don’t bother their horses. At least, this is what I understand to be the case. There are specific rights of way that (I think) you’re meant to stick to, which I have discerned mostly by vibes. And countryside, if you just go into it—like if you find a green splotch on a map—there are all these things in it.

Not marked trails. This is why Rambling is very different from and far superior to Hiking. But little paths that lead to hills and streams with belts of trees lining them, and then knots of trees that make up a couple of acres of woodland at a time, and foundations of old—this being England, in some cases very old—houses, and at one memorable time, a stone circle, which disappointingly turned out not to have been four thousand years old but instead to have been built as a sort of Year 2K let’s-honor-the-druids project.

Beginning in the early 1800s, the area around Stoke on Trent, which was originally England’s Green and Pleasant Land, began to start feeling the results of the massive coal and flint mining, iron mining, smelting, clay (?) mining? Or something? and above all the coal-burning of the furnaces of the old potteries. The descriptions aren’t far off of Mordor. No one born there ever really saw the sun, or the sky, or took a clean breath of air. They just didn’t. It was dark satanic mills for five generations or more.

Beginning in the 1970s, various aggressive clean water and clean air bills, and massive investment in landscape rehabilitation, and above all the end of the ongoing poisoning of earth, air and water, began to have their own effects. The landscape—with all its bitterns and chaffinches and moles and voles and probably vales and hedgerows and so on—reasserted itself. The sense you get in walking in the Staffordshire countryside is the sense of the Hopkins poem that His Majesty King Charles read and tweeted out (he probably didn’t tweet it personally) the other day.

For all this, nature is never spent.

Now, the countryside I walk out into is far closer to the countryside as it was before the Industrial Revolution—much more built up, of course, but not nearly all built up, not even close. There are canals—those remnants of industry are its most permanent legacy on the landscape—but they, given rest from the sludge that had been dumped in them and given loving attention, have become an interlacing of nature preserve throughout the whole country, combined with a bikable transportation network. People fish in them, now. Egrets fish in them too. Ducks and geese and swans swim in them, and the geese in particular have taken to them with a kind of Teens Hanging Out on Streetcorners menace. I always feel, walking towards a flock of geese, that they might beat me up because I'm not one of the cool kids.

You can get to two different canals easily from our house, and they’ll take you off into the countryside. Let me explain again that this is all walkable from our front door. You walk for about half an hour to 40 minutes in most directions and you’re out of town. I did this once as an experiment in one direction, towards one green swath on the map, and it worked beyond my wildest dreams. The second time I brought Alastair and this neighbor girl who has become a good friend. And even with a whole afternoon worth of rambling, we only got a little ways into the green bit to the North-East of our house.

The phenomenon of getting our bikes and figuring out the canal network and the rest of the UK cycling network is an aspect of this too—but walking—rambling—is perhaps even more powerful than cycling because you can do it on any surface, not just roads or tracks, and you can climb over things and up things easily, and you don’t have to worry about remembering how to get back to your bike if you lock it up and leave it somewhere. It’s a bit the way I’ve always felt much more independent in a city with a public transportation system and no car: if you have to leave your car somewhere you always have to figure out how to get back to it; it’s a sort of psychic drag on any flânerie you might want to do. (Also I am a very very bad driver).

The most similarly powerful transformation of being in the world I’ve ever experienced was the first time I climbed over the fence on the harbor-wall down by Pier 17 to get onto the schooner I deckhanded on for a couple of years: maritime perception of the world felt like unlocking something like a new physical skill. All the water you see around a city on an Island like Manhattan becomes not a pretty background to a selfie but something to be interacted with.

I imagine birds must perceive the air in much more highly agentic ways than we do. Like, it’s not just… air. There are currents, there are updrafts, there are things you can DO with and in this, with your body. I believe the term is affordances. That is how I felt about New York Harbor when I started sailing. And now it’s how I feel about the Countryside.

The other aspect of this newly discovered way of being in the world is that you can essentially count on there being a pub not too far from wherever you finally find your way back onto a paved road.

Now, however, I am flying (not by myself, I am not a bird, but in an airplane) (It’s just occurred to me that airplane pilots also probably feel agentic about the air, but I think it must be different because they are physically enclosed, unlike on a sailboat or on a bike or on foot). I am flying back to NYC. I know the kind of freedom and affordances I feel walking its streets. But I may have to try to figure out whether there is any Countryside in America that I can get to.

The Red Heifer and the Coherence of Numbers

To many of its readers, the book of Numbers might feel like rummaging around in the attic of the Pentateuch, filled with assorted odds and ends that did not fit in elsewhere. Law, narrative, ritual, texts about the division of the land and much else are jumbled up together and it is difficult to discern any unifying themes or logical coherence.

In this case, initial appearances can be misleading: closer examination reveals rich thematic unity in the book, and textual connective tissue where most presume that it is absent. I recently interviewed Michael Morales about his wonderful new commentary on the book, within which he explores many of these commonly neglected features. Morales suggests that an overarching theme of the book is the camp.

The book of Exodus concluded with the construction of the tabernacle and the descent of the Lord’s glory upon it, establishing the tent as the Lord’s dwelling. However, it is in the book of Leviticus that we see the tent of dwelling become the tent of meeting, as the Lord establishes the sacrifices and the work of the priesthood. Numbers takes things a step further, ordering the rest of the people in a war camp arrayed around the tabernacle.

The children of Israel are a people defined by the fact that the Lord dwells in their midst. However, this proves to be less pleasant than it sounds. Due to their unfaithfulness, the Lord strikes them with plagues, his anger breaks out against them, the earth swallows up rebels. By the end of Numbers 17, the people don’t know what to do:

And the people of Israel said to Moses, “Behold, we perish, we are undone, we are all undone. Everyone who comes near, who comes near to the tabernacle of the Lord, shall die. Are we all to perish?” Numbers 17:12-13

Yet one would think that the camp of the Lord is where you would want to be! God is the God of life and holiness and life in his camp is defined by these things. The problem seemed to be that the Israelites Moses was leading were a people touched by death and characterized by unfaithfulness and the closer they came to the Lord, the more the volatile incompatibility of death and wickedness and life and holiness became clear. You want to be in the realm of life and holiness, yet what if you are sinful and polluted by death?

Behind this, Morales and others suggest that we can hear the narratives of Genesis 2-4. The camp is like the Garden, where the Lord walks in the midst and man enjoys fellowship with him. Outside is the realm of banishment, where man—like Adam and Eve, and later Cain—is judged, excluded from the source of life, returning to the dust in death. To be sinful and touched by death in the presence of God is to be liable to judgment.

Recognizing the thematic unity that the camp gives to the book in general is very illuminating. However, there are also threads that bind seemingly disparate sections together. One example of this is the tassels law in Numbers 15:37-41—

The Lord said to Moses, “Speak to the people of Israel, and tell them to make tassels on the corners of their garments throughout their generations, and to put a cord of blue on the tassel of each corner. And it shall be a tassel for you to look at and remember all the commandments of the Lord, to do them, not to follow after your own heart and your own eyes, which you are inclined to whore after. So you shall remember and do all my commandments, and be holy to your God. I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt to be your God: I am the Lord your God.”

At first glance, the tassels law seems to be randomly situated. However, to those who read more carefully, it is immensely important and ties up with much in the context: to the failure to enter into the land, to the looming question of Israel’s fate, and the passages that follow.

The tassels law alludes to the rebellion of chapters 13 and 14: they are not to ‘spy out’ (rendered as ‘follow’ in the ESV quoted above) after their own heart (verse 39). This is a key word of chapters 13 and 14. The tassels recall the rebellion at Paran, where Israel heeded the unfaithful spies and failed to enter the land. Among other things, the tassels function as a cautionary memorial of it.

Its allusion to ‘whoring’ after their heart and eyes also recalls things such as the law of the adulteress in chapter 5. They must be (re)dedicated to the Lord, like the Nazirite of chapter 6 who contracted uncleanness from a dead body, learning the lesson of the adulteress and holding fast to their holy status.

The tassels that mark Israelites out as holy connect them with the garments of the high priest. There is a wordplay between the word for the plate (צִיץ tzitz) on the high priest’s forehead (which reads ‘Holy to the Lord’) and the tassels (צִיצִת tzitzit) on the corners of the Israelite’s garments. The cord of blue also evokes the garments of the high priest in Exodus 28 and the sanctuary items that were covered in blue cloth in Numbers 4.

The implication that every Israelite is holy also leads naturally into the accusation of the rebellious Korah in 16:3: “You have gone too far! For all in the congregation are holy, every one of them, and the Lord is among them. Why then do you exalt yourselves above the assembly of the Lord?” The tassels law thus segues between the rebellion at Paran and that of Korah.

Wordplay between tzitzit and tzitz also connects the tassels law with the demonstration of Aaron’s authority with the blossoming rod in Numbers 17: the blossoms of the rod, like the plate on the high priest’s forehead, is referred to using the term tzitz. The connection between the almond blossoms and the plate on the forehead of the high priest also highlights the symbolic association between the high priest and the lampstand.

With the tassels, the blossoming of Aaron’s rod frames the rebellion of Korah. The holiness of all the people is asserted, while responding to Korah’s protest. The tassels law thus allows for a very fluid movement from the failure to enter the land to the resolution of Korah’s rebellion.

Furthermore, the placing of the tassels law—also when we consider its juxtaposition with the execution of the Sabbathbreaker that precedes it—is noteworthy due to its implicit narrative location, following the great rebellion in refusing to enter the land. In its narrative situation, it serves to reaffirm Israel’s holy status: despite their failure, the Lord has not rejected his people. They can recall and reject their past rebellion against him and cleave to his covenant. They are still a holy people, dedicated to the Lord.

Here I would like to consider another example of a strange law or ritual that accomplishes an important purpose in its situation in the text of Numbers: the ritual of the red heifer.

I have already noted the importance that Morales gives to the theme of the camp in the book of Numbers, something which assists us in interpreting the red heifer ritual, which is about re-entering the camp after corpse pollution. Besides this broader theme in the book, there is the more immediate context provided by the aftermath of the rebellion of Korah, most notably the fear of the people on account of the holy presence of the Lord in the tabernacle at the end of chapter 17.

Pollution by contact with a corpse, a situation for which the red heifer ritual is designed, is mentioned previously in the context of the law of the Nazirite. The Nazirite vowed himself to the Lord, but the text describes something going awry: someone died near to him and the Nazirite had to undergo a purification ritual and begin his vow again. This, in miniature is the story of Numbers as a whole: Israel vowed themselves to the Lord as his holy army. However, they were polluted by death and had to undergo a period of exclusion, before being cleansed and starting again.

We are not used to rituals and sacrifices. They seem bizarre and foreign to us. There are, however, worse ways to think of them than as effective enacted prayers (I have discussed the sacrificial system in more depth here). The sacrifice acts out through symbols the spiritual reality of what is happening and, through a faithful acting out, the prayer is answered. As the New Testament makes clear, there is nothing about the symbols in themselves that made them effective—it is not that the blood of bulls and goats can take away sin—but God who promised to answer such enacted prayers.

In Numbers 19, the ritual of the red heifer is instituted. This is easily one of the strangest of all the rituals of the law. Besides several strange features of the rite itself we might well wonder what it is doing in its current position. One of the questions that is presented to us by this ritual is whether it should be understood as a sacrifice. While Gordon Wenham argues that it is not a sacrifice, Jacob Milgrom argues that it is. In verse 9, it is described as a purification offering. Yet in contrast to typical purification offerings none of the animal seems to be burnt up upon the altar. The part that is burned is incinerated outside of the camp in a clean place.

Nevertheless, there are important similarities with the logic of the purification offering. We find the relevant law of the purification offering in Leviticus 4:4-12.

He shall bring the bull to the entrance of the tent of meeting before the Lord and lay his hand on the head of the bull and kill the bull before the Lord. And the anointed priest shall take some of the blood of the bull and bring it into the tent of meeting, and the priest shall dip his finger in the blood and sprinkle part of the blood seven times before the Lord in front of the veil of the sanctuary. And the priest shall put some of the blood on the horns of the altar of fragrant incense before the Lord that is in the tent of meeting, and all the rest of the blood of the bull he shall pour out at the base of the altar of burnt offering that is at the entrance of the tent of meeting. And all the fat of the bull of the sin offering he shall remove from it, the fat that covers the entrails and all the fat that is on the entrails and the two kidneys with the fat that is on them at the loins and the long lobe of the liver that he shall remove with the kidneys (just as these are taken from the ox of the sacrifice of the peace offerings); and the priest shall burn them on the altar of burnt offering. But the skin of the bull and all its flesh, with its head, its legs, its entrails, and its dung—all the rest of the bull—he shall carry outside the camp to a clean place, to the ash heap, and shall burn it up on a fire of wood. On the ash heap it shall be burned up.

In the case of the regular sin or purification offerings for the people, the priest can consume the sacrifice. The priest’s holiness trumps the uncleanness, as it were. This does not, however, apply in the case of the sacrifice of purification for the priests themselves, which besides the portions presented on the altar and the blood, must be incinerated outside of the camp. The blood of the red heifer is not offered on the altar because it is an ongoing purification as Milgrom observes. The purification offering can defile those who handle it.

And this is similar to what we see in Leviticus 16:23-28. The purification sacrifice absorbs the impurity that it purifies and must therefore be eliminated. While these things purify, those who handle them are in danger of contracting impurity from those things that purify, because purification offerings bear the impurity that they remove from people.

Something of this logic can be seen in Leviticus 6:24-30.

The Lord spoke to Moses, saying, “Speak to Aaron and his sons, saying, This is the law of the sin offering. In the place where the burnt offering is killed shall the sin offering be killed before the Lord; it is most holy. The priest who offers it for sin shall eat it. In a holy place it shall be eaten, in the court of the tent of meeting. Whatever touches its flesh shall be holy, and when any of its blood is splashed on a garment, you shall wash that on which it was splashed in a holy place. And the earthenware vessel in which it is boiled shall be broken. But if it is boiled in a bronze vessel, that shall be scoured and rinsed in water. Every male among the priests may eat of it; it is most holy. But no sin offering shall be eaten from which any blood is brought into the tent of meeting to make atonement in the Holy Place; it shall be burned up with fire.

In consuming the sin offering, in Leviticus 10:17, the priests are said to bear the iniquity of the congregation. They are able to absorb in some sense that impurity and to overwhelm it on account of their holiness. However, the impurity contracted by something that is used to make atonement for the Holy Place is too great and so cannot be consumed without contracting an overwhelming impurity.

Perhaps the best way to understand the red heifer ritual is as a portable purification offering. The application of the water for impurity does not need to be performed by a priest or Levite. The presentation of the blood of the animal and the preparation of the ashes needs to be performed by the priest, but this creates the materials that can be applied by an Israelite lay person at some later point. This would also serve the practical purpose of allowing for someone excluded from the camp to participate in a sacrificial ritual.

Why is a red heifer used for this ritual? The red heifer would be the largest female animal within the sacrificial system. The ashes that it produced would be able to function for much of the population. Within the laws of the sin or purification offering, the bull represents the priest and the whole congregation. Using a red heifer would distinguish this purification from that purification sacrifice. Female animals were used as the purification sacrifices for lay persons and this was one such sacrifice.

The redness of the heifer seems to strengthen the connection with blood, as does the use of red cedar wood and scarlet yarn. The word used for red (אֲדֻמָּה adumah) also likely puns upon other Hebrew words. It puns upon the word for blood (דָּם dam) and also the words for man (אָדָם adam) and earth (אֲדָמָה adamah), all things with which other associations could be made.

These connections are likely significant. Before the animal is burned, some of its blood is taken by the priest and sprinkled seven times towards the tabernacle. The seven-fold sprinkling of the blood is similar to other blood rituals. For instance, the blood is sprinkled with the priest’s finger seven times before the Lord, in front of the veil of the sanctuary, in the purification offering for the priest or for the whole congregation in Leviticus 4. Blood is also sprinkled seven times in a similar manner on the day of atonement, and also as part of the ritual for the cleansing of lepers and for leprous houses. The blood of the animal is not brought inside the tabernacle, perhaps because the impurity in such a case does not extend as far into the tent as it would in the case of an impure priest.

The parts of the animal that are incinerated to obtain the ashes are the same parts of the animal that are burned of the purification offering in Leviticus 4, Nothing here is said about the parts of the animal that would typically have been offered to the Lord. To the parts of the animal that were incinerated, the priest had to add cedarwood, hyssop, and scarlet yarn, elements that recall the ritual for the cleansing of lepers in Leviticus 14:3-7.

Then, if the case of leprous disease is healed in the leprous person, the priest shall command them to take for him who is to be cleansed two live clean birds and cedarwood and scarlet yarn and hyssop. And the priest shall command them to kill one of the birds in an earthenware vessel over fresh water. He shall take the live bird with the cedarwood and the scarlet yarn and the hyssop, and dip them and the live bird in the blood of the bird that was killed over the fresh water. And he shall sprinkle it seven times on him who is to be cleansed of the leprous disease. Then he shall pronounce him clean and shall let the living bird go into the open field.

The leper has something of the character of a living corpse, so it should not surprise us that there are similarities between the process for the cleansing of the corpse-defiled person and the cleansing of the leper. The items added to the burning red heifer also recall, like the elements of the ritual for the cleansing of the leper, the Passover: cedarwood recalls the doorposts, the scarlet yarn recalls the blood on the doorposts, and the hyssop, the hyssop with which the blood was sprinkled upon them.

The account of the Passover in Exodus 12, the ritual for the cleansing of the leper in Leviticus 14, and the ritual of the red heifer in Numbers 19 are the only three occasions where hyssop is mentioned in the Pentateuch. In the ritual of the red heifer, as in the ritual for the cleansing of the leper, the blood is applied not to the objects of the tabernacle but to persons. We should bear in mind that the objects of the tabernacle often symbolize persons in some way, so the application of blood to tabernacle items could be seen as the symbolic application of the blood to persons.

Why these three cases? Perhaps because each of them involves a sort of movement from death to life. The Passover is deliverance from the death of Egypt into new life as the people of God. The ritual for leprosy cleanses someone from the death of exclusion from the camp and the impurity of a skin condition that has death-like characteristics. And the law of the red heifer cleanses someone from corpse pollution and exclusion, bringing them back into the life of the camp.

Blood was not usually applied directly to individuals, merely to objects representing them. However, there were various exceptional occasions where blood was applied directly to individuals. In the initial establishment of the covenant in Exodus 24:8, Moses cast blood on the people. In the priestly ordination ritual, blood was applied to the extremities of the priest’s bodies. A similar application of blood occurred in the ritual for the cleansing of the leper.

The ritual of the red heifer has, as Milgrom notes, similarities to the ritual of the Day of Atonement, which was, with the two goats, an intensified form of the purification sacrifice. It also has similarities to the ritual for the cleansing of lepers. However, in contrast to both of those rituals, there is no dispatching of one animal into the wilderness or open field. The application of blood to the bodies of persons should also be considered in light of the different foci of impurity. Many of the purification rites are principally dealing with ways that the sanctuary and its objects have been rendered impure as a consequence of the people’s behaviour, not so much the impurity of the people themselves.

The impurity of the leper, the corpse-defiled person, or the person with a bodily omission is an impurity of their own bodies, not an impurity of the tabernacle caused by their actions. Consequently, some form of purification needs to occur on their own bodies, not just on the tabernacle objects. The deep strangeness of this ritual suggests the possibility that there is deeper symbolic import to what is taking place, perhaps that like the ritual of jealousy, it relates to events in Israel’s history.

Animals in the sacrificial system have their particular type stipulated. They must be of the herd or the flock, or goat or sheep. Often the sex of the animal is stipulated. It must be a male of the herd or a female of the flock. Not infrequently, we also see the stipulation of the age of the animal, of the first year, or perhaps a mature animal. The red heifer is exceptional in being an animal whose colour is stipulated, and as we’ve already noted, besides the colour associated with blood, the word has connotations.

The cluster of associations I mentioned above between the redness of the heifer, the earth, man, and blood might bring us back into the world of Genesis 2-4. Adam, the man, is created out of the adamah, the earth. In chapter 4, Cain’s shedding of his brother’s blood leads to banishment. In the ritual of the red heifer, we have allusions back to the exile of man from the realm of God, from the garden, to the defiling character of blood as we see in chapter 4 in the story of Cain, and to the way in which man returns to the dust and to ashes.

As human beings, we are but dust and ashes. When we die, we are reduced to those elements. In this chapter, the ashes of the red heifer are referred to both as ashes and also as dust in verse 17. In being associated with blood and with dust and ashes, in an especially pronounced manner, the red heifer ashes could be regarded as a sort of symbolic distillation of death.

Recognizing such associations, Joel Humann argues that there is an analogy between the tabernacle and the garden of Eden. Both are sanctuaries of the Lord’s dwelling. Banishment from Eden in Genesis placed man in the realm of death. Banishment from the camp or the Promised Land involves a similar sort of death and alienation. The story of the beginning of Genesis might also be recalled in the emphasis upon the third and the seventh day. The third day recalls the third day of the creation, where the land is brought up out of the waters, and the seventh day recalls the Sabbath, the rest, and the completion of the creation.

Reflecting upon these connections further, we should consider the way that chapter 19 is situated within the larger book of Numbers. Why is the institution of the ritual placed here? The answer to this question, as Humann argues, will be found by considering the narrative context. He writes,

But intentional juxtaposition is the key to its placement—the Red Heifer itself thematises the narrative at this point. The wilderness is “preeminently a place of death for Israel, which must die to be reborn.” The heifer, as a symbol of the old generation Israel, is reduced to dust in the wilderness; by means of the ashes of the heifer and living water the one contaminated by death is restored to a living relationship with God, even as the new generation is transferred from the wilderness to the land of promise. The heifer immediately foreshadows the impending final elimination of the old generation, and symbolises the promise given to the new. “Future life in the land will replace the pervasiveness of death in the wilderness.”

Humann’s argument can also help us to understand this chapter as filling the great gap in the book of Numbers, a jump from the second year of the Exodus to the conclusion of the forty-year period of the wilderness wanderings. The ritual of the Red Heifer is a symbolic representation of this entire period. The dying off of the old generation, connected with symbols of the initial Exodus and Passover, will lead to the cleansing of a new generation and the entrance into the land.

In the next chapter of the book of Numbers, the key figures of Miriam and Aaron die and the imminent death of Moses is also declared. After their deaths and the dissolution of the whole original Exodus generation, the people will finally be prepared to enter the Promised Land. The death of Miriam, and its connection with the miraculous provision of water that follows (Numbers 20 contains the first such provision of water mentioned since Exodus 17, which answers a water crisis that seems to arise directly at the death of Miriam) might suggest further associations. Perhaps Miriam should be associated with the red heifer, her death providing a sort of atonement. This might also be related to the way the death of the high priest ended the banishment of the manslayer (Numbers 35:25-34).

Morales suggests the possibility that there might be allusions to the ritual of the red heifer in places like Ezekiel 36-37, where sprinkling the purifying water of the Spirit is followed by the raising of the people’s bones. The ritual of the red heifer is also mentioned in Hebrews 9:11-14, where the efficacy of the blood of Christ is compared to the much lesser efficacy of the ashes of the red heifer:

But when Christ appeared as a high priest of the good things that have come, then through the greater and more perfect tent (not made with hands, that is, not of this creation) he entered once for all into the holy places, not by means of the blood of goats and calves but by means of his own blood, thus securing an eternal redemption. For if the blood of goats and bulls, and the sprinkling of defiled persons with the ashes of a heifer, sanctify for the purification of the flesh, how much more will the blood of Christ, who through the eternal Spirit offered himself without blemish to God, purify our conscience from dead works to serve the living God.

The blood of Christ does not merely overcome banishment from the camp as the red heifer does, but opens up a ‘new and living way’ into heaven itself. However, there is another twist in the way that Hebrews presents Christ as the fulfilment of the purification offerings. In Hebrews 13:10-14 we are told:

We have an altar from which those who serve the tent have no right to eat. For the bodies of those animals whose blood is brought into the holy places by the high priest as a sacrifice for sin are burned outside the camp. So Jesus also suffered outside the gate in order to sanctify the people through his own blood. Therefore let us go to him outside the camp and bear the reproach he endured. For here we have no lasting city, but we seek the city that is to come.

If entrance into heaven comes through the provision of purification and the overcoming of death in resurrection life, the movement out of the camp suggests a different direction of movement, a movement out into death and banishment. In Hebrews, Christ does not die so that we might not have to, but in order that we might participate in his once-for-all efficacious death, dying with him and rising to eternal life. The movement out of the camp is our dying with Christ. Those who undertake this movement are assured of its associated movement, into heaven itself.

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ On Mere Fidelity, Derek, Matt, and I discuss some recent controversial remarks by N.T. Wright. Matt and I also talked with Ephraim Radner about his recent book, Mortal Goods.

❧ The Theopolis Podcast’s Deuteronomy series continues, with episodes on Deuteronomy 31: The Looming Death of Moses, Deuteronomy 32: The Song of Moses: Part 1, and Deuteronomy 32: The Song of Moses: Part 2.

❧ My series of videos for Theopolis on a Pentecostal politics continues with an episode on Pentecost, Political Power, and Persuasion.

And another on Political Community and Unity in the Spirit.

❧ I was invited onto the Expositors Collective podcast to discuss sermon length, and why there might be some benefits to shorter sermons.

❧ L. Michael Morales is the author of a new two-volume commentary on the book of Numbers in the Apollos Old Testament Commentary series (Numbers 1-19 is already released and Numbers 20-36 is forthcoming). He has fascinating insights on the war camp of Israel, described in the opening chapters of Numbers, and joins me to discuss some of them.

❧ I recorded a version of my reflection on Good Samaritan Politics, which I first wrote for the Anchored Argosy back in 2023.

Upcoming Events

❧ Alastair has several smaller events coming up. He will be speaking and preaching at a couple of churches in the Stockport area in just over a month’s time.

❧ The next session of Theopolis’s Civitas group starts on the 14th November.

❧ Alastair will be participating in the next session of Davenant’s ongoing Lilly Grant-funded program working on congregational life in a digital age.

❧ Much of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Alastair and Susannah

I enjoyed the vicarious rambling. Here is a fun and informative piece about the birth of the movement in England:

https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/right-to-roam/

America is a patchwork when it comes to walking the country. Of course, in the West, public land abounds, and is abutted by towns and cities, so something like an English walking experience can be had; in the East, not so much, with the much more restrictive property boundaries.

Transforming from landlubber to tar is a heady experience. The water not only becomes a new entity in its romanticism, but after a scrape or two, you realize that it can now also kill you... which somehow only adds to the romanticism. We channel the spirit of our risk-taking forebears in a modern world where life-and-limb risk now seems rare.

Hopkins' invocation of Psalm 2 in connection with the landscape of industry is classic English pastoral. Will Christ really judge the industrial revolution with his rod? I have my quibbles, but there's no debating that those landscapes are hellish in our imagination. Both seafaring men, and grimy coal miners, are icons of the great enrichment which took place during that time, but in our minds we connect the mill towns with hell, and the sea with heaven. I'd wager many more sailors died than miners.

It's a blessing that we now live on the far side of the great enrichment and have been able to clean up our wetlands, channels, hillsides so spectacularly in the developed world. And enjoy rambling through the landscapes. Repairing our damaged world is like bringing in the new heavens and earth. Well, probably not "like", more like "is".

Yet, where there are no oxen, the manger is clean...

I think businesses had to learn the hard way how to price in cleaning. It's much the same in households. Every time me, the wife, and kids start a project, we never budget the time or money for tidying up.

"God's Grandeur" is hard to beat... for my money, only "Kingfishers" edges it out, for beauty and pith.

Here's Richard Burton reading a long one.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WhQwFf6Qb9U

I feel the same way about walking - I just spent three days walking from Ribblehead to Bowness and the fact that you can walk for days in the countryside (and sleep in B&Bs and pubs) is really special.