Dear Friends,

Alastair: After all the travelling to Durham, York, and London, we have passed a less eventful fortnight, spending most of our time in Stoke-on-Trent.

Davenant’s Michaelmas Term is nearly over, with only marking remaining. The final Theopolis podcasts of 2023 are recorded and the last Pesher session of the Fellows Program happened about a week ago. The concluding recording session of my series on Revelation with the God’s Story Podcast was also a few days ago. I’ve submitted several articles, am starting to get on top of a backlog of correspondence, and am hoping to finish some larger writing projects. It is a pleasant shift in pace and focus.

Christmas is also rapidly approaching. Most of our presents have been purchased. My brother and his family are coming over from Germany in under a week’s time. Susannah is making lots of gingerbread and cookies.

Susannah: And other things, though not to the degree of last year’s mad gilding fest. It would be so good if there were like two months of the year that were bracketed out for making and sending gifts, and two months’ worth of income that could be spent on them and on postage. My ambitions always exceed my grasp Christmaswise.

Susannah went down to Darvell, the Bruderhof community in East Sussex, last Saturday. Unfortunately, I was unable to join her, as I had classes to teach. However, we met up on Sunday afternoon in Oxford.

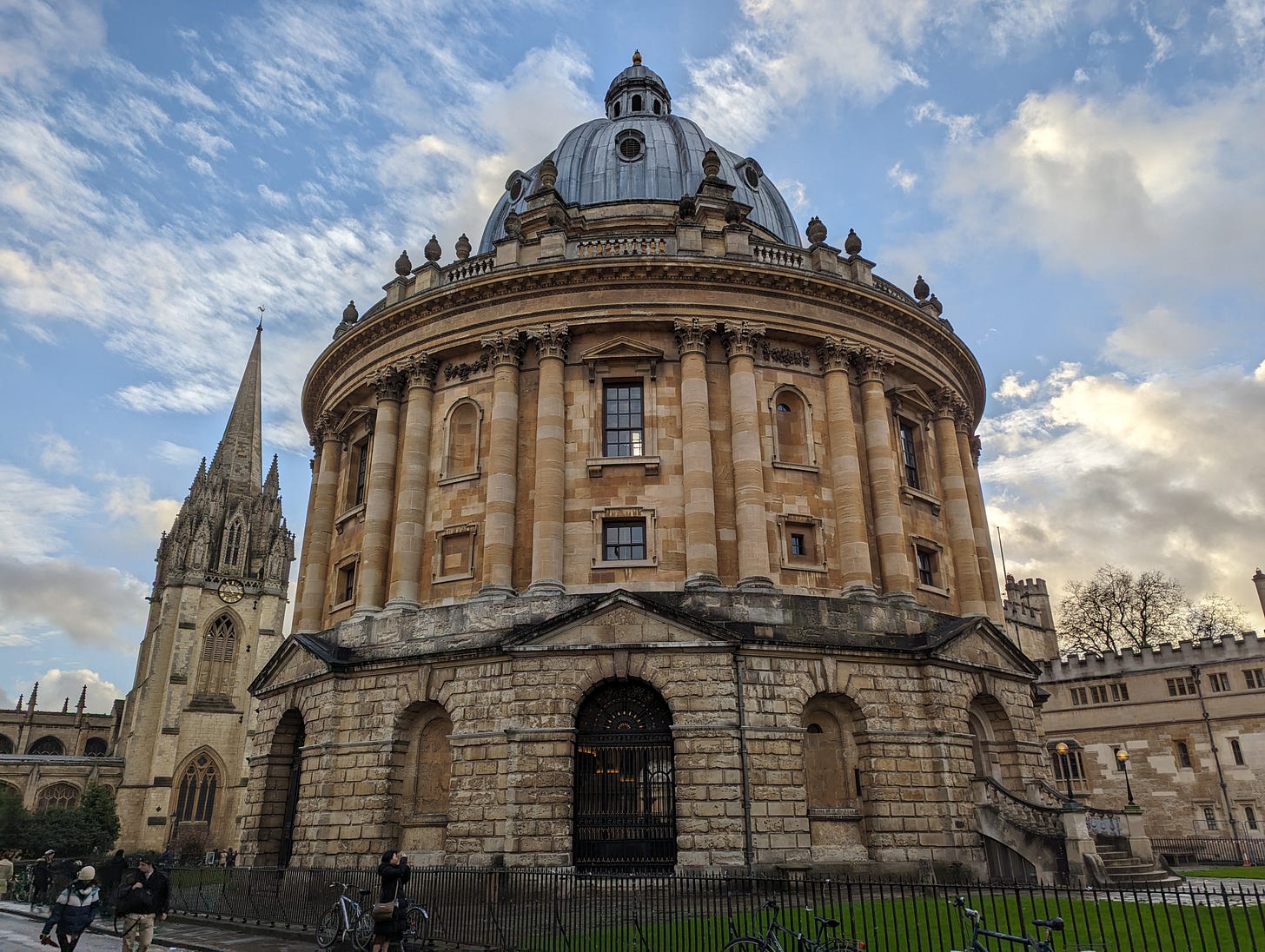

We both love Oxford. The city has a personal significance for us, as it was where we decided to become a couple back in March of 2020 (in the station, just as Susannah was about to leave!). However, even without such a personal significance, we would still love the place. It an entrancing city, both beautiful and inspiring.

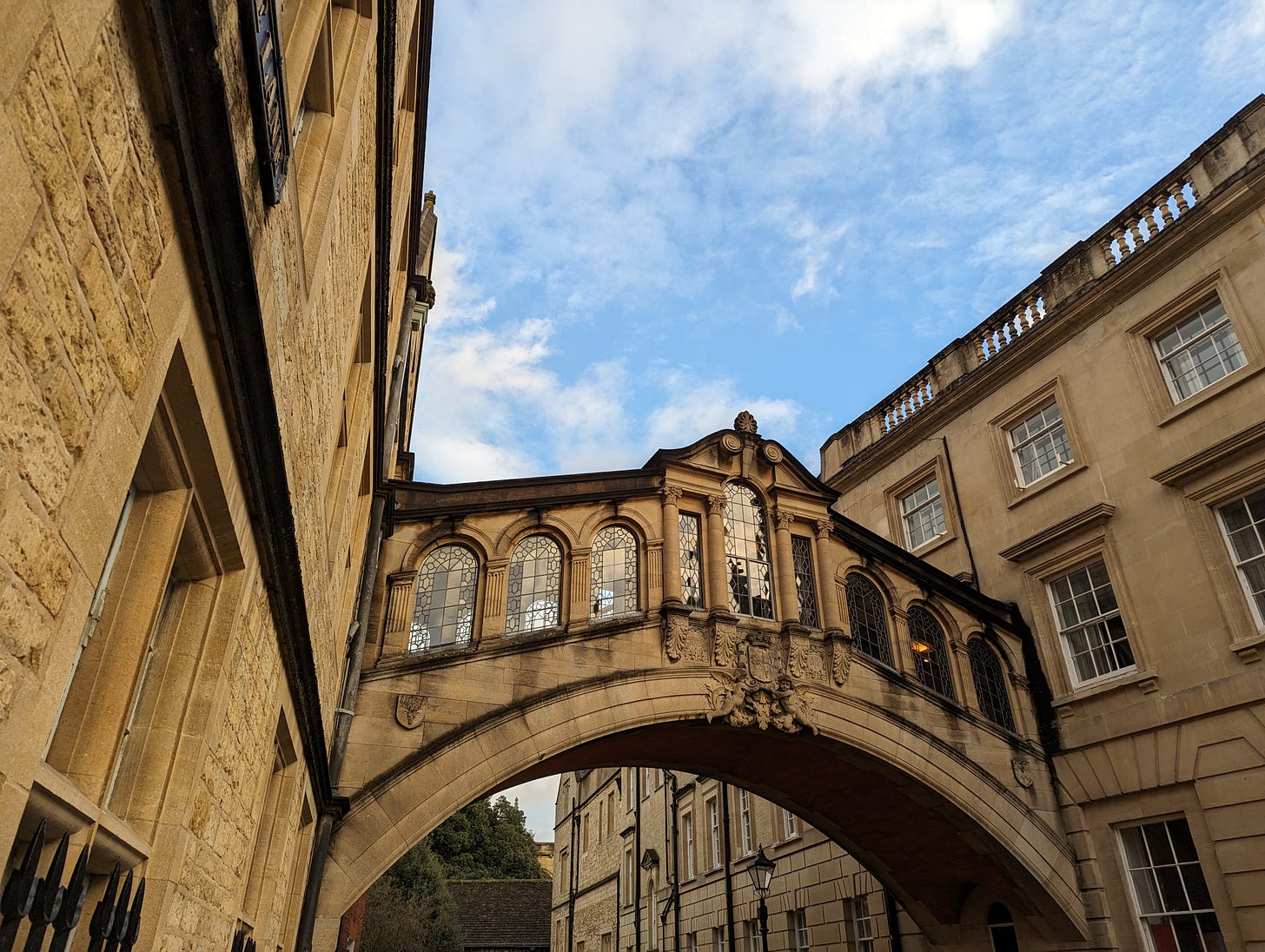

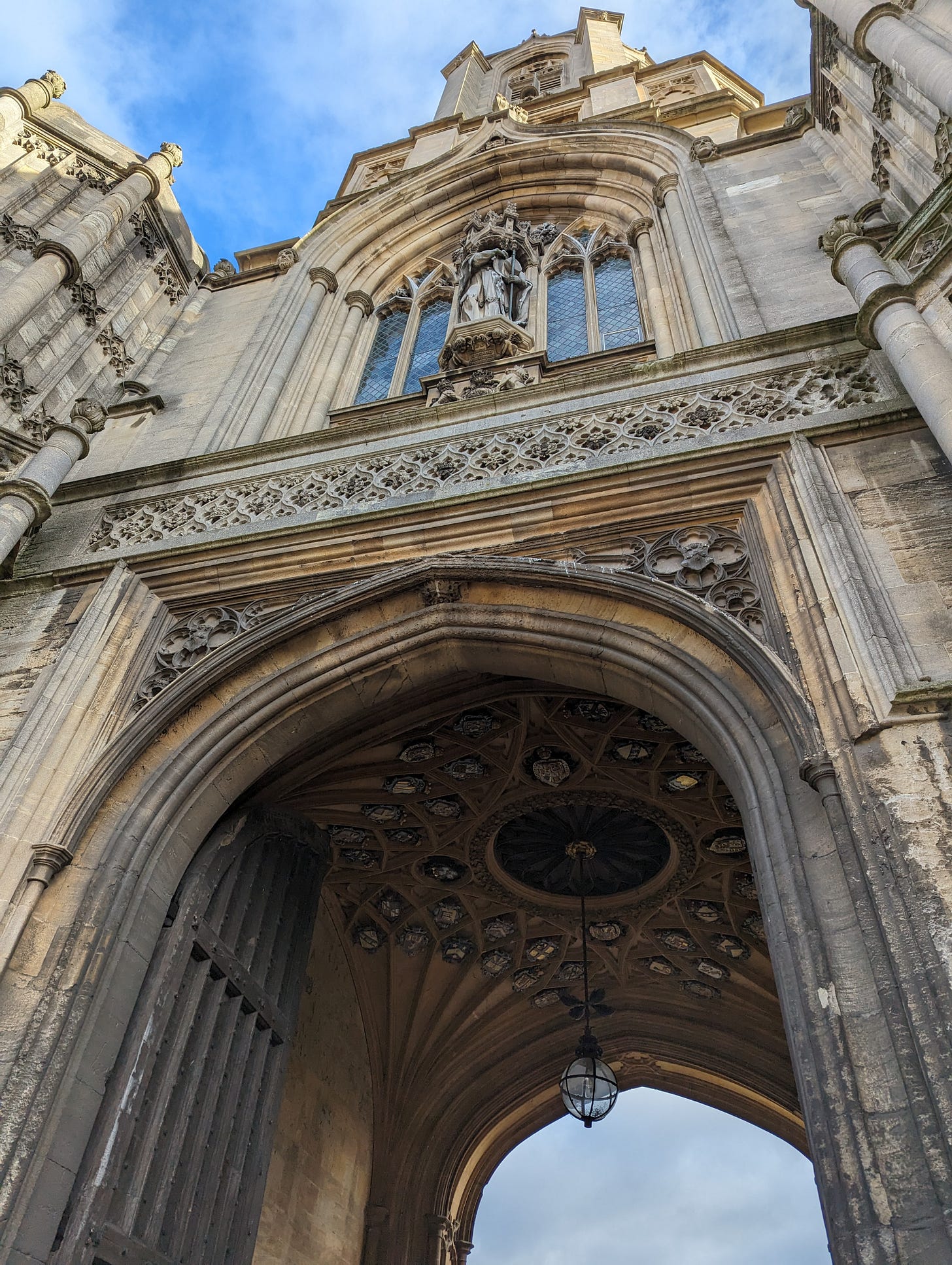

I arrived in the middle of the afternoon and, while Susannah was being delayed by the chaos and disorder of the British rail network, wandered through Oxford and took in some of the sights. There are few cities that are as dense with architectural wonders as Oxford and one can ever only see a few of them on any given visit, not least because many of them are not accessible to the general public and you need to have friends with time and the necessary privileges.

An online friend from Australia was spending a few weeks in Oxford with his family. We very happily talked theology for a couple of hours, before joining his family—and Susannah, who had just arrived—for a pub meal. They will actually be in New York City in the early new year, where Susannah will likely spend time with them again.

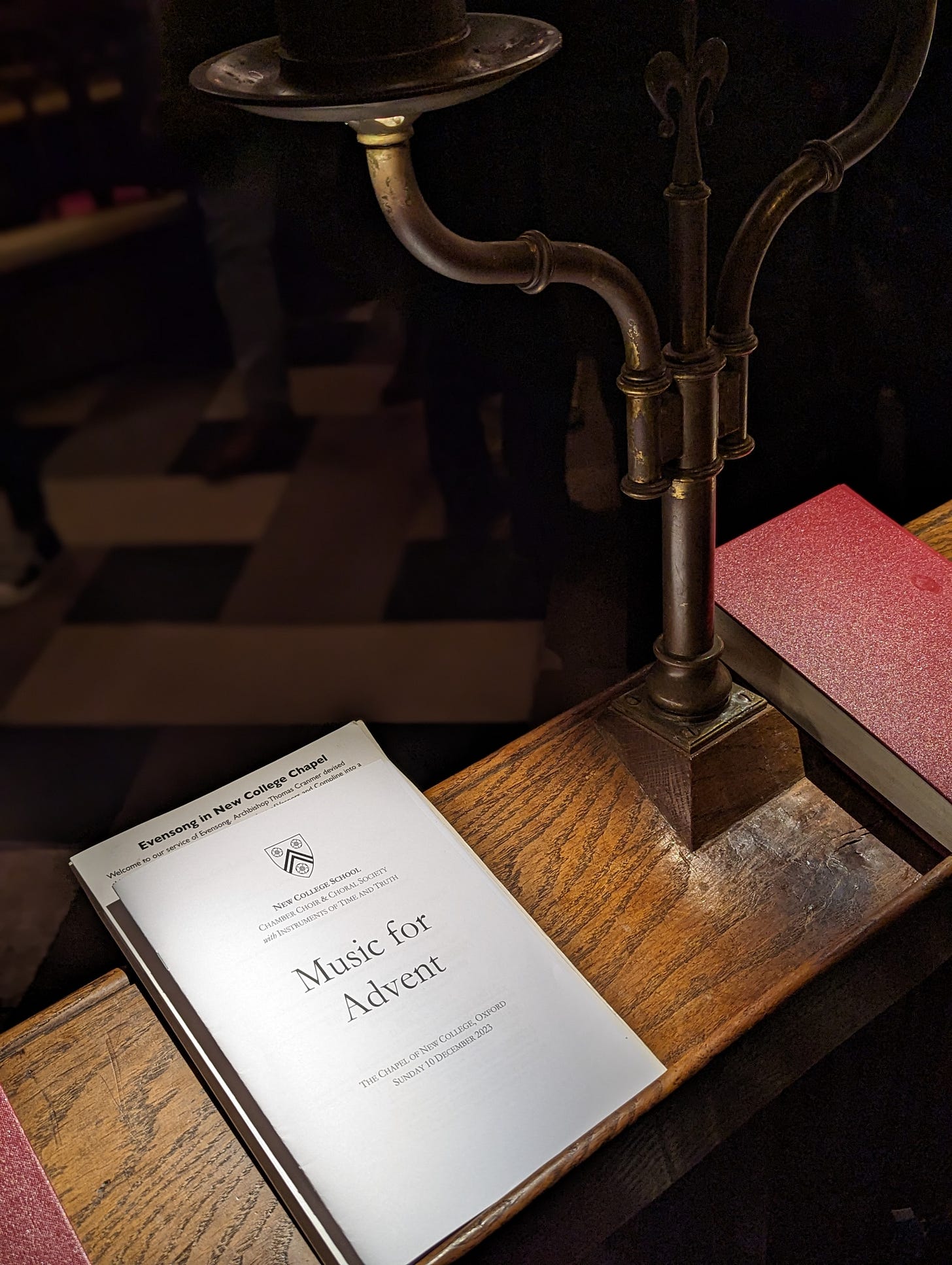

I had bought tickets to a performance of Advent music that evening at New College: Bach’s Cantata Wachet Auf! along with Haydn’s Missa Sancti Nicolai and Symphony No. 11 in E flat. As one would expect from such a context, the music was glorious. Wachet Auf! weaves together scriptural themes from Matthew, Isaiah, the Song of Songs, Revelation, and elsewhere in Scripture (you can read a translation here). Listening to the remarkable performance of the piece, while meditating on the text, has been the most powerful evocation of an Advent mood for me so far this season.

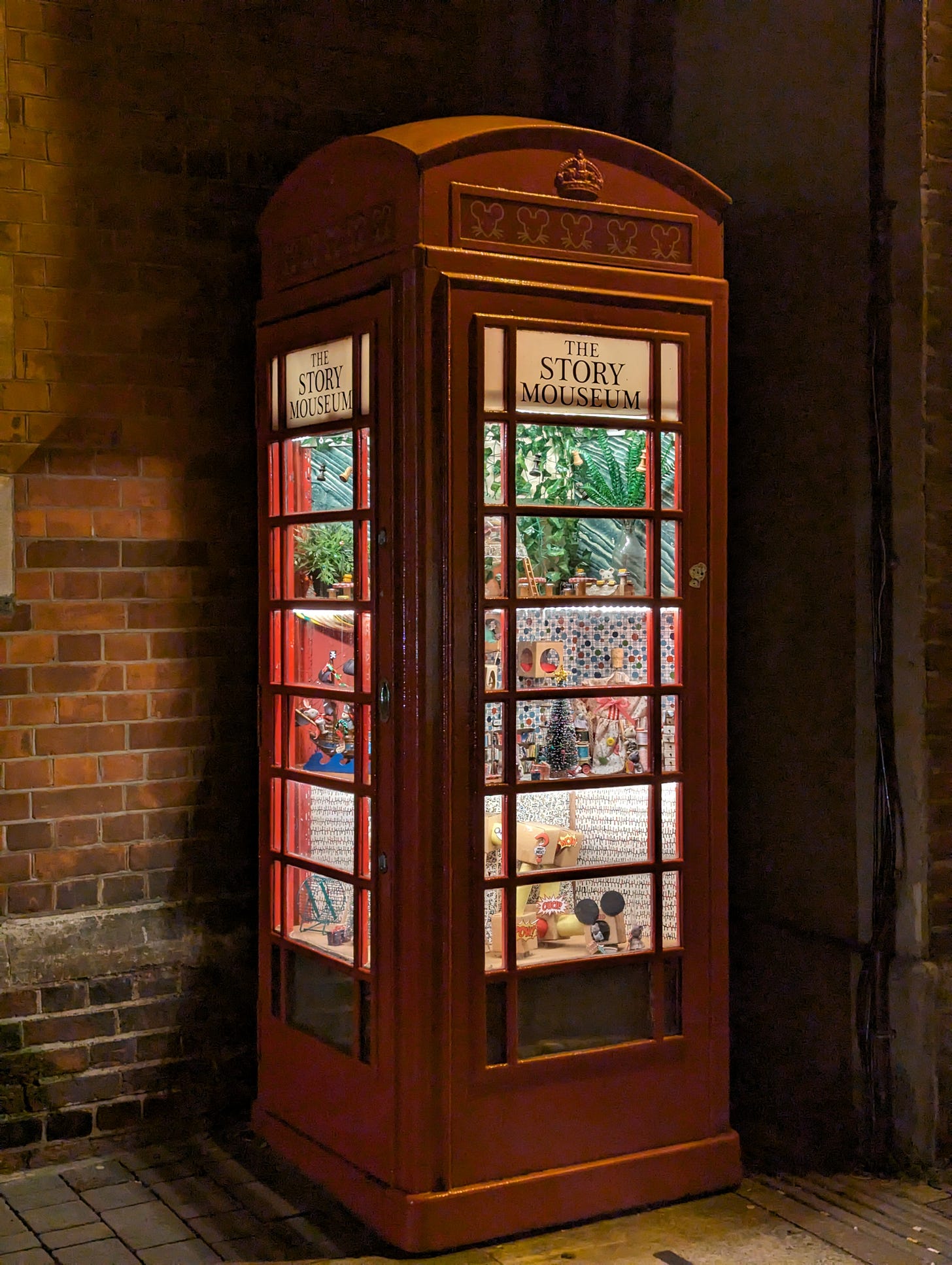

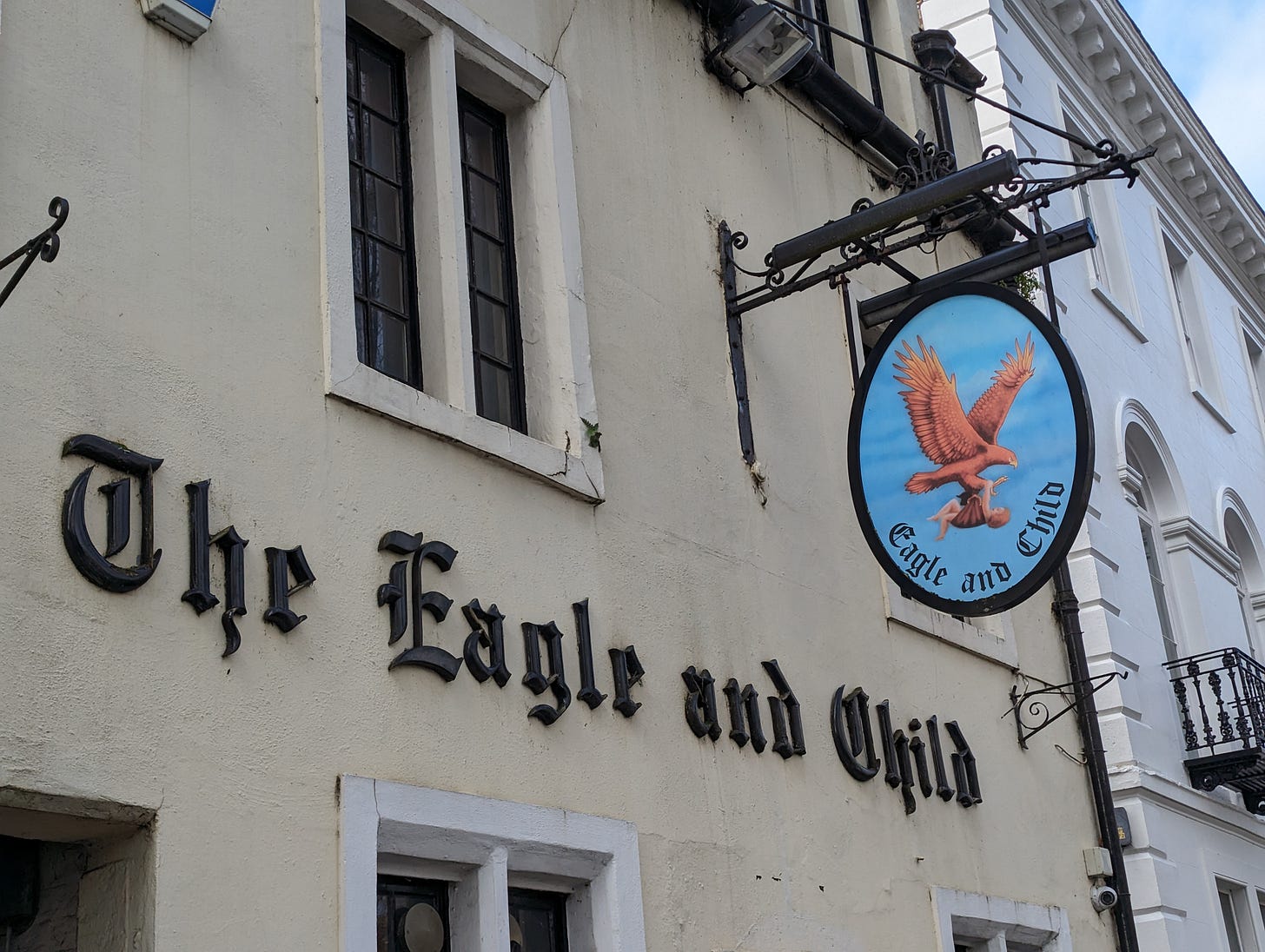

Monday morning we made a visit to St Philip’s Books, one of one favourite bookstores, and also took the opportunity to look around the city and do some Christmas shopping. We also visited The Eagle and Child pub, famously associated with the Inklings; sadly, it is still closed and it is far from clear to me that Tolkien and Lewis would be sympathetic to the technology-focused vision of the new owners.

Every time that we visit a city like Oxford we have several friends, acquaintances, and contacts who want to meet up with us, and there are always at least a few friends with whom we do not get to spend any time at all. We largely spent the afternoon meeting up with some online acquaintances, with whom we enjoyed some very stimulating and exciting conversations.

An important element of my work has always been travelling and connecting with people—the number of people whom I have met in person after first getting to know them online is probably well north of three hundred at this point, possibly even nearer to five hundred. However, since marrying Susannah, I have travelled and connected with people more extensively than I had previously. While this has definitely reduced my work on some fronts—and pushed me well beyond my temperamental preference for solitude, quietness, familiarity, and settled routine—it has expanded, altered, and invigorated it on others.

Connecting with people, exchanging ideas, and getting to know their projects has been a source of countless serendipitous interactions, which have catalysed ideas and ventures for us and for our friends both old and new. Reading through the book of Acts, I have often considered the extreme importance of a relatively small class of early Christians who travelled frequently and extensively, serving thereby as connective tissue for the growing early Church, encouraging the crosspollination of ideas and the sharing of ministries and resources, and enabling a consciousness of united identity and interests to arise through the communication of news, prayers, and teaching. While Susannah and I have very deep roots on both sides of the Atlantic (we live in the apartment where Susannah spent the first few years of her life in NYC and fifteen minutes’ walk from my parents’ house while we are in the UK, where I lived since I was a teenager), we also have lives and vocations that take us to dozens of cities and countries every year.

After a meal, we travelled back to Stoke, where we will largely be until the end of the Christmas period.

On Friday, I decided that, as it is only fifteen minutes’ drive away from us and as neither of us had seen it before, we should take a couple of hours to visit Little Moreton Hall. Little Moreton Hall is a delightfully eccentric example of Tudor architecture, mostly built in the mid-1500s. It is surrounded by an attractive yet modest moat, which could never have served much of a defensive purpose, but which is doubtless appreciated by the ducks.

If I have ever seen a comparably peculiar building, it is not coming to mind. There is probably not a single level floor or ceiling, or a straight wall in the entire building. It is a warren of rooms, with little apparent logic to many of them.

The most impressive room of all is the Long Gallery, with a plaster image of Fortune on the tympanum on one end and an image of Destiny on the other. With its oak beams, the design of its windows, and the rolling unevenness of its floors, walking through the house one can occasionally imagine oneself at sea in a Tudor warship. There are various charming carved figures on headboards, gables, and at the porches.

The building is currently hosting a Christmas through the ages exhibition, but the interior of the house is fascinating enough with the need for any added features. One of the more surprising things within was a series of paintings of the Apocryphal story of Susanna and the Elders.

Yesterday, we had a visit from relatives—an uncle, aunt, and one of my cousins—and we spent a very pleasant afternoon with my parents and my brother and sister-in-law.

Susannah: As Alastair mentioned, I spent a night at the Darvell Bruderhof community in Sussex - we had a UK Plough Christmas party, featuring the traditional feuerzangenbowle. This is an Austro-Hungarian imperial cavalry Christmas tradition which has been adopted by the Bruderhof, involving balancing a sugar cone over a bowl of wine, soaking the cone in rum, and setting it on fire; the sugar melts and drops into the wine, mulling it; originally the cone was balanced on a pair of crossed cavalry sabres, though that has been modified for contemporary households which have less reliable access to such things. We also engaged in the somewhat less traditional Shane McGowan tribute listen-through to the Pogues’ Fairy Tale of New York.

I was honored to be asked to speak at the Bruderhof Sunday meeting about Plough, my work for it, and what it is that we’re getting up to at this magazine that is the community’s main public outreach. This is what I said:

When I was in the process of conversion, it was, as it often is, terrifying. One of the things that was terrifying was that there was so much that I loved about being human—good fiction and music and intellectual adventures and experiencing nature and careful thinking—and I didn’t know how of all those human things would look in light of the Gospel, with all its urgency.

Plough demonstrates, with each issue, what I found out gradually in the process of conversion and the rebuilding of life on the new foundation of Christ that you do after you are converted.

Plough presents a picture of a complete human life—one where, having been redeemed by Christ, we are set free to actually be human well.

So we have stories, poetry, art; essays that contain some of the best thinking and writing on pressing issues of the day as well as evergreen questions; theological and biblical essays; interviews, and profiles of “doers,” people who are living out the life of the sermon on the mount, creatively, every day. We also have sketches of Bruderhof life, and beginning with the coming issue, we will have more profiles of community life and Bruderhof members, to show readers one way of living out Christ’s call, that I’ll be for the most part writing.

Eberhard Arnold wrote in 1920 of Plough that

With breadth of vision and energetic daring, our publishing house must steer its course right into the torrent of contemporary thought. Its work in fields that are apparently religiously neutral will lead to new relationships that open new doors for our life’s most important tasks.

The magazine is still doing this work, which is new every year and every generation.

The N.I.C.E. Has Bought The Eagle and Child, Apparently

From the Department of Distressing Developments: When we were in Oxford, we went on pilgrimage to the pub where Tolkien, Lewis, Williams and Barfield habitually met: The Eagle and Child, known to the Inklings as The Bird and Baby, carries special memories for us as well, as we went there on our first trip back to Oxford as a couple. The pub closed during Covid, and I’d vaguely heard of various groups aiming to buy the building and re-open it as a pub.

Apparently, that’s off the table, at least for the moment. The building has been bought or leased by a group called The Polaris Fellowship, a nine-month long part-time fellowship aimed supporting young people, mostly graduates of Oxford, Cambridge, and Imperial College London.

One hates to judge a book by its cover or a fellowship by its logo and the text of a vague one-sheet pasted up outside its future home. When I saw this, however, I thought “Oh they’re Thiel people. The N.I.C.E. has bought The Bird and Baby.”

One hates to make hasty judgments. And so one does research.

Polaris is a program of Entrepreneur First. Its aim is to identify and create a community of young people it expects to become, essentially, the next generation of tech gurus. Polaris does not directly aim at helping these men and women found companies, although that’s the purpose of EF. Instead, it aims to help them become founders in spirit: it educates them in the catechesis of Silicon Valley founderism and encourages them to propose their own roles or projects within the world that is the intersection of high finance and high tech.

EF was founded in 2011 and is, like YCombinator, a Silicon Valley culture influenced startup incubator. It is larger than YCombinator, though not nearly as well known. It is… very large. As of 2022, EF has had more than 3,000 people go through its program; they have founded more than 300 companies collectively worth over $10 billion. And while YCombinator invests in companies, EF invests primarily in people: it focuses on identifying very young people, often in or just out of college, who it aims to shape into the next generation of “founders.” From its own website:

EF is funded and backed by some of the world's best tech founders and company builders, including Patrick and John Collison (Stripe); Reid Hoffman (LinkedIn), Tom Blomfield (GoCardless and Monzo), Sara Clemens (Pandora and Twitch); Nat Friedman (GitHub); and Matt Mullenweg (Wordpress).

And what does Polaris aim to do?

“We give you,” says the website, “the freedom, resources, and privacy to pursue mastery of the established and the discovery of the heretical.” The program talks about the importance of knowing about movements that have in the past brought the kind of drastic cultural change that it aims at: the three movements it cites as historical inspirations are the Enlightenment, the Counterculture, and Cyberculture.

Ved Nathwani, one of the first cohort, describes his experience of his cohort, meeting together in London, as

a little haven of thought machines whirring away at times, questioning the world around us, human nature, and fundamental aspects of how we live and how society shapes us. Diving into all sorts of weird and wonderful topics from examining how movements are formed and anarchism to Brain-Computer Interface (BCI). It sounds pretty rogue, for a fellowship which was essentially an initiative of Europe’s most successful tech incubator.

He was surprised by “how STEM-heavy the cohort was. There were more Imperial PhDs than social science and humanities students/grads alone, and I found huge value in being in a peer group with such a diverse makeup.” These future founders included “AI safety experts, and PhDs in VR and techbio, intelligence, space and EdTech enthusiasts.”

He talks about an afternoon, late in the fellowship, when he met up with one of his fellow members:

[We] were both questioning what Polaris had done to our thinking, how existential we felt, and how so much of what we thought was ‘real’ was actually, just a construct of the environments and people who we surrounded ourselves with.

Our cohort WhatsApp chat might be called “Our Cult,” but at different points in history, many viewed what today we see to be societal movements, as cults.

The rhetoric is very familiar to those who have been immersed in Silicon Valley “founderism”: “Few things matter more,” says EF’s web copy,

than what the world’s most talented individuals do with their lives.

As a founder you have the opportunity to shape mankind’s future in profound ways.

We identify and invest in exceptional individuals. People with enormous potential, insatiable curiosity, and an impatience for impact. We amplify the exceptional.

Our programs liberate you from artificial limits, backing you to become the founder of a company no one else could build.

And are they Thiel people?

Of course they are. Nathwani describes a curriculum ranging “from Zero to One by Peter Thiel, to the Bible, from John Stuart Mill to books on Counterculture and CyberCulture.” Thiel is also probably the most-quoted source in articles discussing Polaris and Entrepreneur First.

I am going to make a prediction. That prediction is this: the sections of the Bible assigned included the Tower of Babel, reinterpreted, and the Aqedah—the Binding of Isaac—and perhaps sections of the passion narratives, along with a Rene Girard text as commentary.

Tara Isabella Burton, in her recent Self-Made: Creating Our Identities from Da Vinci to the Kardashians, has the best discussion I know of of the development of the vision expressed by this fellowship and its associated organizations, which one might call the Silicon Valley Sublime. She examines “founder culture” as an outgrowth of the work of such people as Buckminster Fuller and Stewart Brand, the founder of the Whole Earth Catalogue whose career has bridged hippiedom and libertarian cyberculture, but whose motto (“We are as gods and we might as well get good at it”) has remained the same. “Of course,” writes Burton,

Brand had a very particular kind of human-god in mind: one that looked and sounded a lot like Stewart Brand. The ideal reader of the Whole Earth Catalog was a “Thing Maker,” a “Tool Freak,” a “Prototyper.” He was a committed autodidact, suspicious of social norms, fervent in the pursuit of his own self-fulfillment. He was a modern-day swashbuckling entrepreneur with a talent for programming. He was simultaneously part of a new community— that of his fellow commune members, who had, like him, opted out of society at large—and more independent than ever before. He was untethered by the obligations and expectations in to which he had been born.

This vision is the one picked up by Thiel and his co-author, onetime Senate candidate Blake Masters, in Zero to One, and it is very much the vision of Polaris. “The book’s title,” explains Burton,

doubles as a paean to human ingenuity: to go from zero to one is to create something ex nihilo, the prerogative of geniuses rather than ordinary men. Zero to One sees the start-up founder as the ultimate creator, a secular inheritor to both the Renaissance genius and the mature Enlightenment man, cutting himself off from custom’s leading strings.

Thiel is very well known as an avatar of this world, Brand less so. Perhaps even less recognized is Max More, whose Extropian movement was, ironically enough, founded in Oxford.

Extropianism is more or less synonymous with today’s Transhumanism—it is perhaps a brand of Transhumanism, as Kleenex is a brand of tissue.

“We will ignore,” More wrote in 1990,

the biological fundamentalists who will invoke ‘God’s plan,’ or ‘the natural order of things,’ in an effort to imprison us at the human level… To fully flower, self-transformation requires a rebellion against humanity.

As Burton describes this move,

The idea already implicit in so much of the post-Enlightenment narrative of self-creation—that to become your truest and best self, you had to cut yourself off from society at large—had here become explicit. Nature, custom, society—all of these phenomena paled in comparison to what individual human beings could do to rewrite the story of humanity itself.

Quoting heavily from Nietzsche, More argued that self-transcendence was a moral responsibility and, furthermore, the very foundation of the human condition. “Self transformation,” he wrote, “is a virtue because it promotes our survival, our efficacy, and our well-being. As a dynamic process of self-overcoming, an internally generated drive to grow and thrive, it is the very essence and highest expression of life.” That self-overcoming could mean life extension. It could mean the abolition of aging, sickness, depression, and other physical ailments. Or it could mean getting rid of the human body altogether, instead adopting “the creation of faces and voices as synthetic means of expression.” It could mean “transhumanism”: transcending the human condition by transforming the body into equal parts flesh and machine.

This new Internet-infused culture would draw on both the aristocratic tradition of Nietzschean self-making—with its obsession with powerful individuals whose desire for power would allow them to reshape a fundamentally meaningless world—and the democratic, capitalist American obsession with self-optimization as a moral calling.

It is this world, this vision, that Polaris belongs to. It resembles nothing so much as a libertarian-inflected version of what Lewis in the third of his Space Trilogy called the N.I.C.E., the National Institute of Coordinated Experiments. Lewis dramatized in that novel the insight that he explained straightforwardly in his essay The Abolition of Man: “What we call Man's power over Nature turns out to be a power exercised by some men over other men with Nature as its instrument.”

Several months ago, I recorded a podcast examining the parallels between Silicon Valley transhumanist founder culture and That Hideous Strength, along with my Plough colleagues Marianne Wright and Peter Mommsen. We discussed these ideas extensively: the N.I.C.E. is, I said (sorry for quoting myself, very tacky)

a vision of technological society that is seeking to do what technological society, starting with the Tower of Babel, has always done, which is to reach heaven on our own terms without being subject to God’s rule and to make ourselves gods.

It is rare that an intellectual or cultural movement declares itself entirely openly. Often one has to read between the lines. That is not the case here. I can think of few cultures more opposed to the embodied Christian humanism of the Inklings than the Silicon Valley Sublime of Polaris.

Still… the one thing one can say about this sort of thing is that it won’t last. Tech startups, and their associated programs, are always popping up with blueprints, or at least napkin sketches, for a brand new millennium. Oxford will last. The pub building will last, too. And the imaginative world at the back of The Eagle and Child will be around long after its current leaseholders have gone on to other things. Polaris’ tenancy will then become part of the story of the place, the fact of its absurd Sauron-like pride something to wonder at in future Oxford December evenings when the pub has been turned back into a pub, and the old sign hung again.

The good thing about finding oneself temperamentally opposed to a culture that urges its adherents to “move fast and break things” is that if one moves slowly and repairs things, one tends to turn out well.

Stewart Brand himself knew this, describing it in his 1995 book How Buildings Learn, a synthetic work that describes the way that buildings adapt as they are “constantly refined and reshaped by their occupants,” claiming that “architects can mature from being artists of space to becoming artists of time… More than any other human artifacts, buildings improve with time—if they're allowed to. How Buildings Learn shows how to work with time rather than against it.”

The Bird and Baby will learn.

Good Samaritan Politics

In his 2017 book, The Political Samaritan: How Power Hijacked a Parable, Nick Spencer examines various ways that the ‘Parable of the Good Samaritan’ has been deployed in British political discourse. Especially for generations that grew up with a basic biblical literacy, the Parable of the Good Samaritan is a morally resonant part of a shared cultural canon, while not being explicitly connected with Christianity’s more particularist features.

Spencer considers some of the contrasting ways the parable has been directly referenced and subtly alluded to in British political speech over the past fifty years. For Margaret Thatcher, he argues, the Good Samaritan illustrated her claim that you need to ‘have in order to give’ or perhaps that you need to ‘give from yourself and don’t ask the state to give anything’ (The Political Samaritan, 159). New Labourites advanced different readings. For many of them, the point was to ‘do something’, not to ‘pass by on the other side of the road’. If the Thatcherite reading emphasized the importance of the private prosperity and self-sufficiency encouraged by capitalist free enterprise, and the moral dangers of dependence upon government, the New Labour reading served to justify a range of interventionist and activist policies, from increased social welfare to military action against ISIS.

Terms and expressions drawn from the parable and its retellings—especially ‘good samaritan’ or ‘pass by on the other side’—have been absorbed into popular parlance. People speak of a ‘good samaritan’ as an individual who acts selflessly on behalf of a stranger, while ‘passing by on the other side’ refers to morally culpable indifference to visible need, when we would be able to assist. Yet, as Spencer suggests, the Good Samaritan might appear to be ‘a half-dead metaphor, lying on the edge of our linguistic highway’, its biblical source forgotten. As the parable has been forgotten and as expressions and images drawn from it have become familiar, they have lost much of their arresting power and, in their more clichéd uses, can even serve to dull our thinking with their platitudinous quality.

The familiarity of the expressions drawn from the parable imply a simple reading of it that essentially renders it a fable, for whose ‘moral’ they are shorthand. Read in such a manner, the parable is a general story about taking concern and action for strangers in need whom we encounter (occasionally with the added suggestion that this should be done even for those who are outsiders or from undesirable classes of persons). Abstracted even further, it can become a story about the morally obligatory character of interventionist action and policy. The generality and abstractness of the ‘moral’ of the story so construed allows it to serve as something of a wax nose justification for a wide variety of different and sometimes even contradictory positions.

Within its biblical context, the so-called Parable of the Good Samaritan, as Spencer notes, is little over one hundred words in Greek. Its import, however, is not so readily abstracted from its textual and cultural context, as that of a moral fable might be. Rather, it is dense with intertextual allusion and association, with significant historical and geographical reference, and with symbolic features. It also assumes and operates upon an extensive body of cultural and religious beliefs, values, and understanding in its primary hearers.

While some might suppose that the value of such a parable in our contexts requires that it be able to slip its original cultural moorings, this is misguided. Rather, revisiting and reconsidering the Parable in its historical, cultural, and textual context might help contemporary readers to discover new areas of political salience that it might have in their own worlds. While we need not censure all abstraction of general ‘morals’ from specific biblical narratives, this is not the most fruitful or faithful route to discover illuminating biblical perspectives upon our issues. We will be much more benefited in our study of Scripture when we diligently seek to hear it on its own terms and, having attended to the fulness of its voices, bring them into conversation with those concerns and issues that are native to our own contexts.

In Luke’s gospel, the only gospel within which it appears (Luke 10:25-37), the Parable of the Good Samaritan is part of a longer conversation with a lawyer, someone skilled in the interpretation and teaching of the Mosaic Torah. This individual, seeking to test Jesus, asks him what he should do to inherit eternal life (verse 25). In response, Jesus asks him what is written in the Law and what his interpretation of it is (verse 26). The lawyer’s answer is a model one (verse 27); indeed, with its reference to the first and second great commandments—given in Deuteronomy 6:5 and Leviticus 19:18—it anticipates the answer that Jesus himself gives later in his ministry (Matthew 22:35-40).

Jesus approves the lawyer’s answer, telling him “You have answered correctly; do this, and you will live” (Luke 10:28). The lawyer, however, seeking to ‘justify himself’ (verse 29) asks a further question: “And who is my neighbor?”. Contrary to much popular Protestant exegesis of this and other such passages over the centuries, we should not read into this exchange theological convictions about the impossibility of law-keeping: no evidence of such reasoning is to be found here. While the lawyer’s response might reasonably be interpreted as intended to absolve himself from onerous moral duty and to present himself as being in the right and in good covenant standing, the impossibility of the moral duty is nowhere suggested. It is in response to the lawyer’s follow-up question that Jesus tells the parable.

That the parable is framed by a conversation about the keeping of the Torah, rather than being a standalone moral fable, is far from unimportant. Indeed, it is a key to discerning much of the parable’s meaning. The question of true law-keeping is a dominant one in much of Jesus’s teaching, as it also is in his controversies with the religious leaders of the day. It appears in disputes about Sabbath healings, in his teaching concerning the fulfilment of the Law in the Sermon on the Mount and elsewhere, and in various other halakhic debates during Jesus’s earthly ministry. The Law, we should recall, was the charter of Israel’s existence, given at Sinai after their deliverance from slavery in Egypt. In observing the Law, Israel lived out its freedom and identity and enjoyed the right-standing into which God has brought them.

Alert to this framing, our ears might begin to hear certain key undertones of the parable. Although the questions of ceremonial purity may not be quite as prominent as some have suggested, in the figures of the priest and the Levite we might recognize a form of religion that is narrowly focused on ritual purity to the neglect of compassion. Perhaps they fear that contact with a body that is either dead or near death might render them impure and thereby temporarily disqualified from discharging their religious vocations.

In his Sabbath healings, Jesus emphasized both the priority of compassionate action over narrow halakhic concerns for purity and ritual observance, and the fact that the Torah was chiefly fulfilled in transforming loving initiative. Without opposing ritual observance, purity concerns, and scrupulous attention to the minutiae of the Torah, Jesus made clear that these are ordered and subservient to higher ends. Something similar is evident in the teaching of the Sermon on the Mount, where a loving moral initiative and pursuit of righteousness is the fulfilment of the Law that the Lord desires, not merely a superficial avoidance of sin in which the heart is uninvolved.

The lawyer’s question concerning the identity of his neighbour is one that might be indicative of a desire narrowly to circumscribe the scope of his moral obligations. Rather than taking the sort of loving moral initiative that Christ exemplifies and to which he calls his disciples—the sort of creative and re-creative initiative characteristic of the kingdom of God, transforming, restoring, and forging shalom—the lawyer is seeking a sort of sterile moral purity and standing. Like the priest and the Levite in the parable, the lawyer is preoccupied with his legal and ritual standing in a manner that makes him averse to loving initiative. Rather than seeking to form and extend relations with neighbours as an expression of love and compassion, he perceives such relations as liabilities.

Here it is important to note that the conversation of Luke 10 has several parallels with a conversation that we find later in the central section of the gospel, one which Hobert Farrell has suggested is chiastically paired with it. Luke 18:18-23—

And a ruler asked him, “Good Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?” And Jesus said to him, “Why do you call me good? No one is good except God alone. You know the commandments: ‘Do not commit adultery, Do not murder, Do not steal, Do not bear false witness, Honor your father and mother.’” And he said, “All these I have kept from my youth.” When Jesus heard this, he said to him, “One thing you still lack. Sell all that you have and distribute to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, follow me.” But when he heard these things, he became very sad, for he was extremely rich.

Once again, the question of inheriting—note, not ‘earning’—eternal life is raised and the law is summarized in response (here by Jesus, rather than by his interlocutor). The underlying point is not that law-keeping is impossible, nor that something else overrides it, but that the law is fulfilled in love for God and neighbour. Recognition of the importance of the theme of true law-keeping and the nature of the fulfilment of the Torah in the gospels will greatly colour our reading of the Parable.

The attentive hearer might also discern echoes of certain Old Testament narratives. Peter Williams, in his recent The Surprising Genius of Jesus, suggests the possibility of a subtle allusion back to Genesis 42:18 in Jesus’s statement “do this, and you will live.” In Genesis, Joseph speaks these words to his brothers, who had earlier stripped him and left him half-dead.

There is a further Old Testament narrative that many commentators have heard in the background of Jesus’s parable, a narrative whose importance for our interpretation might be suggested by specific details which it shares with the parable. In 2 Chronicles 28, the southern kingdom of Judah, the capital of which was Jerusalem, suffered a devastating defeat at the hands of the northern kingdom of Israel and their Syrian allies. The men of Israel took captive 200,000 Judahites and were bringing them to Samaria. However, while doing so they were confronted by a prophet, Oded, who warned them that they were calling down judgment upon themselves by taking these captives. The captives, Oded stressed, were their own relatives and, like their brethren from the southern kingdom, Israel too faced divine wrath for their unfaithfulness.

In verse 15 of the chapter, the ears of anyone familiar with the Parable of the Good Samaritan should start tingling:

And the men who have been mentioned by name rose and took the captives, and with the spoil they clothed all who were naked among them. They clothed them, gave them sandals, provided them with food and drink, and anointed them, and carrying all the feeble among them on donkeys, they brought them to their kinsfolk at Jericho, the city of palm trees. Then they returned to Samaria.

The parallels should readily be apparent. Men coming up from Jerusalem had been taken by opponents, beaten and stripped. Men of Samaria, obedient to the word of the Lord, recognized the beaten Jews as their brothers and showed compassion to them, in a manner closely resembling the compassion shown by the Samaritan in Jesus’s parable. Later the men of Judah were brought back to Jericho (the man caught among thieves was on the road from Jerusalem to Jericho).

In discussing the parable, many have considered the Samaritan as a paradigmatic marginalized, distrusted, or even hated outsider. Tensions between Jews and Samaritans are implied at various points in the gospels, not least in the preceding chapter of Luke, where a Samaritan village would not receive Jesus, because he was bound for Jerusalem (9:52-53). I believe that the parallels with 2 Chronicles 28 might suggest a greater degree of significance to the Samaritan’s identity.

The Samaritans were not merely foreigners who lived near to Judea; they were also claimants to Israelite identity and heritage, with their own form of worship and religion that contrasted with that of the Judeans. As Jason Staples points out, they were regarded by many as ‘Hebrews’ and could claim to ‘Israelite’ heritage but were not ‘Jews’, ‘Jew’ being narrower terminology focused on Judeans, whose origins were in the southern kingdom (The Idea of Israel in Second Temple Judaism, 58-83).

The Samaritans were people largely descended from remnants of the ten tribes of the northern kingdom of Israel that were defeated by the Assyrians and admixed with various other peoples (see 2 Kings 17). Luke mentions Samaritans on several occasions in his gospel. However, the most notable appearances of Samaritans in Luke’s writings are in Acts. In Acts 1:8, Jesus declares, “But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you, and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth.” The movement of the gospel mission is from Jerusalem to the wider province of Judea, then to Samaria, and then to all the Gentile nations. Samaria is not here treated as one of the Gentile nations. Indeed, the mission to the Samaritans in Acts 8 receives its own treatment and precedes the gospel going to the Gentiles. Implicit in Luke’s account, I believe, is a theology of the restoration of Israel, of the reunification and regathering of a divided and scattered people. The Samaritans are a key element of this greater picture.

In 2 Chronicles 28, unbeknownst to the men of Samaria, Israel was only a couple of decades away from devastation. In the events of that chapter, Israel was called back to itself, reminded of their covenant kinship with their brethren from Judah, with whom they had been at war. For one fleeting moment, in the Samaritans’ act of compassion to the people of Judah, that kinship was seen in action and the hearer might perceive a glimmer in the gloaming of Israel’s history, a possibility that was never truly realized.

The Parable of the Good Samaritan, with its allusion to 2 Chronicles 28 and its focus on the figure of the Samaritan, is, among other things, a parable about the restoration of Israel. Questions of observance and fulfilment of the Torah were bound up with questions of Israelite identity and destiny. In the Parable, there is a recollection of that brief appearance of Israelite brotherhood in the final years of the northern kingdom. The lawyer’s question—“Who is my neighbour?”—is reframed by another event of compassion in which the joining of divided people is seen.

In the message of Oded in 2 Chronicles 28, the way of compassion for brothers in need stands as the alternative to the broken ‘brotherhood’ of kingdoms alienated from each other and standing alike under divine wrath. As, following the message of Oded, the men of Samaria practice brotherhood towards their relatives from the southern kingdom, there is a brief flickering hope of national restoration in humble repentance, faithfulness, and love.

The good Samaritan presents a similar vision, one with resonance that is not merely about private morality. In the good Samaritan’s act of compassion, we see a small image of a people restored through the loving initiative by which the Law is truly fulfilled, a people who find their identity in the receiving and the showing of mercy and grace. To refuse the way of compassion is to exclude oneself from the great work of national restoration that God is performing. The kingdom of God is characterized, not by people who justify themselves, but by helpless recipients of mercy who will show mercy in their turn.

Jesus turns the question of the lawyer on its head. Questions about neighbours are most typically considered in the context of settled life. However, Jesus situates the question in the context of the road, a place where the existing bonds of community are weakened or absent and where people chiefly engage with strangers. For the lawyer, it was the status of potential ‘neighbours’ that was in question; Jesus turns the question against him, essentially asking the lawyer whether he was a neighbour. Jesus also takes a question focused on stable relations and presents an alternative ethic that focuses on creative action and the dynamic formation of new neighbour bonds through love: the Samaritan was not a neighbour but became a neighbour through his compassionate action.

A Christological reading of the figure of the Good Samaritan—one appreciated by many earlier Church readers of the parable—is strengthened by recognition of the chiastic symmetry of the central section of Luke. At the end of Luke 18, Jesus is walking on the road from Jericho to Jerusalem—the reversal of the direction of travel on the same road strengthens the chiastic relation. There is a blind man calling out by the side of the road. While the crowd is passing, those going before Jesus rebuke the blind man and instruct him to be silent. However, Jesus does not ‘pass by on the other side’: he brings the man to him and heals him.

The shape of the parable of the Good Samaritan is, of course, the shape of the story of the gospel: we are those helpless and left for dead by the side of the road and Christ is the one who becomes a neighbour to us in our distress, committing himself to our healing.

In such a Christological reading, other aspects of the parable might appear more piquant. For instance, the figure of the innkeeper, who plays a key role at the conclusion of the parable (Luke 10:35) might stick out to us. The innkeeper is given money and entrusted with a task until the one who gave him the money would return to inspect his work and reward him. The figure of the innkeeper might remind us of the Parable of the Ten Minas in chapter 19. In him we might see an image of the Church, as a minister of the compassion of Christ to whose care Christ has committed recipients of his grace.

Considering the parable in its own world, it should soon become apparent that political meaning was always integral to it. The question of the identity of our neighbour is one that will always be entangled with political considerations for us, and, if anything, it was even more so in Jesus’s day. And in Jesus’s answer, the politically freighted character of the lawyer’s question became far more overt.

Part of the challenge of Jesus’s parable is the judgment that it implies: the priest and the Levite did not prove to be neighbours. In the final assessment, those whose standing in Jewish community might be considered the most secure might find themselves outside of the restored Israel, while Samaritans and abandoned members of the Jewish community might find themselves within.

The Parable of the Good Samaritan has often been understood to teach that everyone is our neighbour. While such a reading might capture something of the parable’s import, it greatly oversimplifies it. The parable presents us with surprising new neighbour bonds formed and sustained in the receiving and giving of mercy, and with parties who, perhaps preoccupied with sacrifice over mercy, have tragically excluded themselves from this new solidarity.

This new solidarity, it seems to me, is most manifest in the Church. The Church is formed by the receipt of God’s mercy in Christ’s and the extension of this mercy to others. The Church is chiefly formed of half-dead recipients of mercy, of those who follow the example of the Samaritan, and of those who minister the mercy of the archetypal Samaritan, Jesus himself, to others in the ‘inn’ of the Church. This solidarity trespasses the bounds of our old solidarities of flesh, cutting across family, ethnic, or national ties. It is a solidarity ‘of the way’, a dynamic solidarity epitomized in loving initiative taken in chance encounters. It is a solidarity in which the intent of the Law is fulfilled in mercy and grace shown to others on our path, beyond existing ties.

This new solidarity does not disband the old solidarities of flesh and blood. However, it consistently unsettles and cuts across them. In this new solidarity—which, as followers of our ‘Samaritan’ Lord, we are actively to advance—we are called to make neighbours of enemies, of outsiders, and of strangers. And these new bonds of the solidarity of the Way will inescapably colour and transform our perception and practice of the settled and given bonds of the flesh, those bonds of family, of kin, of people, and of nation.

Oliver O’Donovan (The Ways of Judgment, 184) expresses well the challenge we must all face:

To each particular identity, then, is put the question: how can the defense of this common good, focussed around this common identity at this time and in this way, be brought to serve that common good which belongs to the all-embracing identity, individual and collective, of God’s kingdom?

Christmas is the time when we celebrate the compassion of Christ, who crossed over from the ‘other side’ of heaven to meet and aid us in our distress. In God’s gracious coming to us in Christ, the pattern of God’s kingdom is revealed: we must ‘go, and do likewise.’ We have been thrown into community with each other within the Church, like a motley group of travellers in an inn. Like the innkeeper, Christ entrusts the Church with the care of new neighbours. At Advent, reflecting upon Christ’s promised return, we are also recalled to our duty to extend and minister the ‘Samaritan’ compassion of Christ to others, as those who will one day give account.

Recent Work

Alastair

❧ Christopher Watkin recently won the Book of the Year award in Christianity Today’s 2024 Book Awards for his Biblical Critical Theory: How the Bible’s Unfolding Story Makes Sense of Modern Life and Culture. Matt and I discussed it with him on Mere Fidelity. Matt, Derek, and I also had a conversation about reputation.

❧ The Theopolis Podcast’s series on Deuteronomy continues with episodes on Deuteronomy 21: Wives of War and Inheritance Rights and Deuteronomy 21-22: A Rebellious Son.

❧ Over the summer, I recorded a series of videos with Joseph Minich. Those videos, along with my series of lectures on wisdom and much more, are available to members of the Davenant Institute. You can become a member here. There is currently a special Christmas offer for a free month of membership, so, if you are interested, now is the time!

❧ If you’ve read my reflection on the Parable of the Good Samaritan in this Substack post, you have been given a small flavour of the sort of thing that I will be tackling in my forthcoming Davenant Hall course on The Bible and Politics. I say a bit more about the course in this video.

❧ As it is Advent season, our minds appropriately return to the issue of eschatology and our Lord’s return. I recently recorded some thoughts on the subject of postmillennialism, partially in response to an article by Jeremy Sexton. I also produced a transcript of the recording.

The question of the theological label that is put on someone’s position might emphasize people’s preferred camps, sides, or tribes. It is like the question of whether you are ‘American’ or ‘Canadian’. And these things can arise more from sociological, ecclesiastical, political, temperamental, confessional, or other such factors. When you remove from the circulation of the conversation those terms that are more about naming camps of theology or opposing ecclesiastical, confessional, or theological groups and focus more upon absolute positions than those diagnostic questions that help to identify them, a very different sort of map can emerge and a very different sense of where people stand relative to each other. Now you are focusing less upon the question of, as it were, what national borders someone lies within than the question of their precise GPS coordinates.

Read or listen to the whole thing here.

Upcoming Events

❧ The third UK Davenant Convivium will be on the 20th January, with Oliver O’Donovan as the keynote speaker.

❧ Alastair’s Hilary Term Davenant Hall course, starting in early January, will be on ‘The Bible and Politics’:

The words and teachings of the Bible are frequently deployed and appealed to in our political discourses. Yet such engagement with the Bible is typically superficial and merely rhetorical; while the Bible affords shallow prooftexts and resonant turns of phrase, it is seldom serving as a deep and guiding source of wisdom in our political thinking. In recent decades, after a long period of neglect, the importance of the Bible’s influence in historic political reflection has received growing attention. In addition to considering such retrievals of the Bible’s significance as a political text for historic thinkers, this course will seek to discover more of the Bible’s enduring insight and generative potential for political reflection. We will investigate some of the variegated ways that the Bible encourages, serves, and directs our political reflection and consider how we can engage with its voice most responsibly and profitably.

You can register for the course here.

❧ The Davenant Institute was recently awarded a prestigious Lilly Endowment grant, which will enable us to establish a project designed to equip Christians for living in the digital age. Alastair will likely be doing a lot of work on this front in the next few years.

❧ Most of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Susannah and Alastair

Susannah- totally feel like you could do a podcast a la Matt Fradds one except for Protestants! It would be so good!

Thanks for the newsletter! It was an especially good one this week.