Dear all,

A blessed Pentecost! We’re back in the US - more about that below. And we’ve been very busy.

The Gilded Age

Susannah: “We are as gods. We may as well get good at it.” That’s the tagline of Whole Earth Catalog hippy ideological entrepreneur-turned-Silicon Valley cybernaut-turned-hyper-long-term thinking plus transhumanism influencer Stuart Brand. Discovering the roots of today’s culture of hyper-online self-creation, this world where we cultivate ourselves through online presence and contemplate uploading our brains, is the job that Tara Isabella Burton has set herself in her latest nonfiction book.

It’s called SELF MADE: CREATING OUR IDENTITIES FROM DA VINCI TO THE KARDASHIANS, though Tara had originally wanted the subtitle to be “How We Became Gods.” And you should pre-order it here: it’s coming out in like three weeks, and pre-orders are profoundly influential market signals in publishing and far be it from me to deny the market its signals.

It’s a dizzying tour of the practice of self-creation, beginning with Renaissance artists and courtiers like Albrecht Durer and Castiglione, then picking up the history of the Dandy from Beau Brummell through Oscar Wilde, and the history of the American self-made man from Frederick Douglass to Andrew Carnegie, and then contemplating the cult of celebrity in the 20th century, from 1920s “IT” girls to Andy Warhol’s Factory, before ending up in our freakish online techno-influencer culture.

One of the most intriguing chapters is the one on American Gilded Age capitalism as a version of the impulse towards becoming godlike. Basically, this is a story about an amazingly powerful memory-holed cultural consensus which prevailed from c. 1870-1920 in the United States. And it was TERRIBLE. Like, based on the standards of orthodox Christian ethics and/or contemporary progressive liberalism, it was I would say significantly worse than anything that has arrived since.

Here’s what it was: Imagine if Bronze Age Pervert and all our contemporary social darwinist post-alt-right vitalists were not anon shitposters but were in fact simply common sense, and normal, and bourgeois, and at the heads of all institutions. This was the worldview of Social Darwinism. As Tara writes,

For English philosopher and biologist Herbert Spencer, the man who coined the phrase, the “survival of the fittest” wasn’t just a scientific fact about animal evolution. It was also, more pressingly, an immutable law about human societies. Spencer was the father of the set of theories known as social Darwinism, a rather simplistic understanding of Darwinian evolution that held, essentially, that all of human life was in competition for scarce resources. Those more capable of amassing wealth—and defeating their fellow man in the process—would live to pass on their genes to their ever more successful children. This was ultimately part of a wider arc of history that would end in humans evolving into their optimal selves. “Evolution,” Spencer insisted, “can end only in the establishment of the greatest perfection and the most complete happiness.

That “happiness” Spencer envisioned, however, wasn’t for everybody. He had nothing but contempt for those he saw as unfit: nature’s rejects, who were either too sick or too stupid or too lazy to attain the success he saw as the powerful man’s due. Ultimately, Spencer predicted, the poor would die out— whether of illness or malnutrition or crime, he didn’t much care—clearing the way for their genetically superior successors. “The whole effort of nature,” Spencer wrote, was to “get rid of” the poor, “to clear the world of them and make room for better.”

Some social progressives of the Victorian era, conscious of the wealth gap that marked nineteenth-century London, advocated for social reform to ameliorate the wretched conditions of the poor. But Spencer rejected such calls as not only unnecessary but actively wicked, an attempt to stem the tide of natural law itself. To keep the poor or sick alive, Spencer insisted, was to keep humanity in an artificial state of inferiority. Rather, “if they are sufficiently complete to live . . . it is well that they should live. If they are not sufficiently complete to live, they die, and it is best they should die.”

Spencer’s view of the world was both scientific (or at least pseudoscientific) and spiritual. His understanding of the divine—he referred to it by the elliptical phrase “the Unknowable”—was certainly not orthodox, but it nevertheless gave a kind of moral valence to the natural order whose principles he so vigorously upheld. If the laws of nature declared survival of the fittest to be the fundamental human condition, then it was morally wrong to interfere. Whatever morality or rightness there existed in the world had to rest in allowing the plan of nature, or the Unknowable, to unfold.

This plan, in Spencer’s understanding, would culminate in humanity reaching its fullest potential. There was no contrast between “nature” and “civilization,” such as we find in, say, the Enlightenment accounts of Locke or Rousseau. Rather, nature and civilization were one and the same. Human social life derived directly from natural law.

Is and ought were identical, but in a way that St. Thomas (and Kant) had never envisioned. Between 1870 and 1920 in the US and, to a lesser degree, in the UK, Social Darwinism was accepted tout court, as an absolutely necessary implication of Darwinism itself (this is what the Scopes trial was about, and the Social Darwinists won the culture, if not the trial). EVERYBODY was into Herbert Spencer. His ideas seemed inevitable, modern, scientific.

Virtually the only holdouts were fundamentalists and Catholics (and shoutout to the Anglo-Catholics! They were big in NYC; Tractarianism had a foothold.) But seriously you didn't have to be particularly liberal or conservative to believe this.

Many, maybe most, mainline protestants were into this. It was the sensible scientific and cultural consensus that trumped more traditional Christian ideas about the good of caring for widows and orphans. It was what non-crazy people believed.

What Nick Land and his Neoreactionaries of a couple of years ago called “gnon” - an inversion of natural law where natural law is understood as the “just” rule of the stronger – was, during that time, simply what science taught and what was true, and was how civilization should be ordered.

More from Tara:

Here we find a somewhat curious reimagining of the medieval view of the role of custom in the social hierarchy. Our Enlightenment authors had rejected custom entirely, and with it the idea that there was anything natural or fixed about one’s social position. But the social Darwinists, and the prophets of Gilded Age capitalism more broadly, renewed the link between the law of nature (a concept that occupied an uneasy middle ground between the explicitly theological “natural law” of Thomas Aquinas and scientific descriptivism) and human social outcomes. There was something running through human life that ensured that the deserving and hardworking achieved economic success and the lazy and indolent remained in poverty. That something, furthermore, had a moral and eschatological purpose: a progressive vision of human life in which each individual was just a link in a much longer chain. Spencer likens civilization to “the development of an embryo or the unfolding of the flower.” It is, in other words, something that has a purpose.

Spencer’s theories were already popular in England. Between the 1860s and the early twentieth century, his books would sell nearly four hundred thousand copies. “Probably no other philosopher,” one contemporary remarked, “ever had such a vogue as Spencer had from about 1870 to 1890.”

Even Darwin himself was astonished—and more than a little horrified—by the public reaction to Spencer’s interpretation of his work. Darwin ironically remarked on how he’d seen in one Manchester newspaper an article “showing that I have proved ‘might is right’ and therefore that Napoleon is right and every cheating tradesman is also right.”

Reading this stuff, it's almost as though the idea of might being for right, and the idea that the weak should be taken care of, that there is a transcendent value in human life, was swept away in a generation – someone born in, say, 1830 and raised in a vaguely Protestant home where you had the idea that you should be kind to the poor, would find himself at age 55 among young people who had simply rejected that whole way of operating.

In its place was the idea of success as the arbiter of natural goodness: success was the metric of justice. And success was measured primarily by wealth. From Tara:

American writers soon took up the drumbeat of social Darwinism, seeing in it a handy way of explaining away Gilded Age social inequality. Among the most influential of these advocates was William Graham Sumner, a Yale political scientist whose 1881 essay “Sociology” used the idea of social Darwinism in support of unfettered, dog-eat-dog capitalism. Economic competition—no less than the competition for food or water or territory among nonhuman creatures—was one of the ways that nature selected for the fittest. The only moral law, Sumner went on to say, was the law of harnessing nature itself, pursuing evolutionary self-interest to its natural conclusion. He rejected the idea that nature demanded any moral quality from human beings other than hard work. Instead, Sumner insisted—in language that echoed Machiavelli’s sexually charged account more than three hundred years earlier—“nature is entirely neutral. She submits to him who most energetically and resolutely assails her. Nature could be harnessed and was malleable. She grants her rewards to the fittest, therefore, without regard to other considerations of any kind.”

Those rewards? Cold, hard cash. Money, for Sumner, was the divine energy of the universe converted into clearly quantifiable capital. “Millionaires,” Sumner elsewhere insisted, “are a product of natural selection.” Any kind of aid to the poor, conversely, was an unnatural “survival of the unfittest.”

Not only was it ethical to seek personal enrichment, Sumner argued, but it was necessary. Amassing money was how you knew you were in sync with natural law in the first place. “It would not be amiss,” Sumner reflected, for children to hear “a sermon once in a while to reassure them, setting forth that it is not wicked to be rich, nay even, that it is not wicked to be richer than your neighbor.”

For their part, millionaires were happy to take this new religion of prosperity as, well, gospel. Plenty of the Gilded Age’s robber barons spoke glowingly of this modern revelation. John D. Rockefeller, at one time the country’s richest man, was also a regular churchgoer and Sunday school teacher at the Erie Street Baptist Mission Church, where he frequently sought to justify his own wealth on religious grounds. In one Sunday school address, Rockefeller summarily informed his young and impressionable listeners that “the growth of a large business is merely the survival of the fittest” and thus a fully appropriate subject to discuss before church.

The Christian squeamishness about the less fortunate had to be squashed. After all, he insisted, “the American Beauty rose can be produced in the splendor and fragrance which bring cheer to its beholder only by sacrificing the early buds which grow up around it.” This wasn’t, he hastened to add, an “evil tendency” but rather “the working out of a law of Nature and a law of God.”

Likewise, another of the Gilded Age’s most successful self-made men, Andrew Carnegie, understood his dizzying wealth as the justified reward of following natural law. In his autobiography, Carnegie describes the first time he read Herbert Spencer on social Darwinism in language that sounds uncannily like a religious conversion.

“Light came in as a flood,” Carnegie recalled, “and all was clear. Not only had I got rid of theology and the supernatural, but I have found the truth of evolution.” That truth was that human beings like Carnegie were supposed to be rich. “Man was not created with an instinct for his own degradation,” Carnegie rhapsodized, “nor is there any conceivable end to his march to perfection. His face is turned towards the light.”

Tara doesn't go into the links of this idea to legal and Comtean positivism, but there's a whole other story there. Suffice it to say, that compared with this wasteland, the early 21st century seems like a paradise of moral reenchantment, positively 13th century in its regard for humans as made in the image of God and the impoverished or weak as deserving special care.

At the very least we do, in our civilization, care for the weak. Perhaps we go overboard in inhumane and irrational directions in this and are too easily bullied by claims of victimhood - yes, that is bad.

But the Gilded Age was, at least in America and somewhat in England, something of an imaginative desert, where the ideas of a good that was not simply success, of a justice that was beyond the rule of the strong, found very little nourishment indeed. A desert of gold dust, parched, inhabited by eugenicists.

That wasn't all it was. Everything is complicated. But I think our visions of progress or decline, whether we are liberal or conservative, must take into account that region in that time.

Our new desert - the one that allows for the growth of euthanasia in its various forms - is somehow linked to that one. I think we need to figure out how.

I should be clear: I’m being very moralistic here, and Tara is not moralistic at all in her book. She’s writing as a scholar and a popular historian; the book contains huge quantities of original research and it isn’t just a popularization of two or three academic Big Books. You should read it because it is extremely interesting and cool and well-written, not for a moral or a takeaway. Nevertheless, this is my substack and therefore I am giving myself permission to be moralistic, and I think Herbert Spencer was a terrible person. Here again is the link to the book.

Happenings and Doings

Alastair: It feels like an age since our last Substack post, although it was only a fortnight ago. The last couple of weeks have been packed, among other things with a great deal of travel. We are now back on in Forest Hills, New York, but about to leave for Davenant House for a few weeks.

Before we left Stoke, we had a delightful visit from our good friend Hannah Long and her parents, who were on a holiday in England. On Saturday 13th, we visited a couple of our favourite places in Stoke-on-Trent with them—Trentham Gardens and the World of Wedgwood—and walked along the canal for a few miles. After church on Sunday we went to Lyme Park, enjoying a spectacular drive through some beautiful parts of the countryside around the Peak District.

Lyme Park is perhaps most popularly known as the setting of Darcy’s estate of Pemberley in the 1995 BBC version of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. Surrounded by a deer park (we saw several deer on our drive in) and stunning formal gardens, Lyme is a glorious place.

We explored the interior of the imposing mansion house, with its grand and sometimes even palatial rooms. The house is filled with fascinating objects, such as the Lyme Caxton Missal, an early printed book of William Caxton’s. On the ceilings of several of the rooms one can also see a dismembered arm holding a cross of St George, commemorating the heroic deeds of Sir Thomas Danyers, who retrieved the Black Prince’s captured standard by cutting off a French knight’s arm. After looking through the house, we walked in the gardens and wider grounds, before having a meal in Disley.

Sunday was also our first wedding anniversary. We never expected that, a year to the moment that we walked down the aisle, we would be standing in front of the setting of Pemberley! The last year has been eventful and joyful, even if not as productive as we might have hoped. We could not feel more blessed with each other or more delighted by the prospect of many further years together.

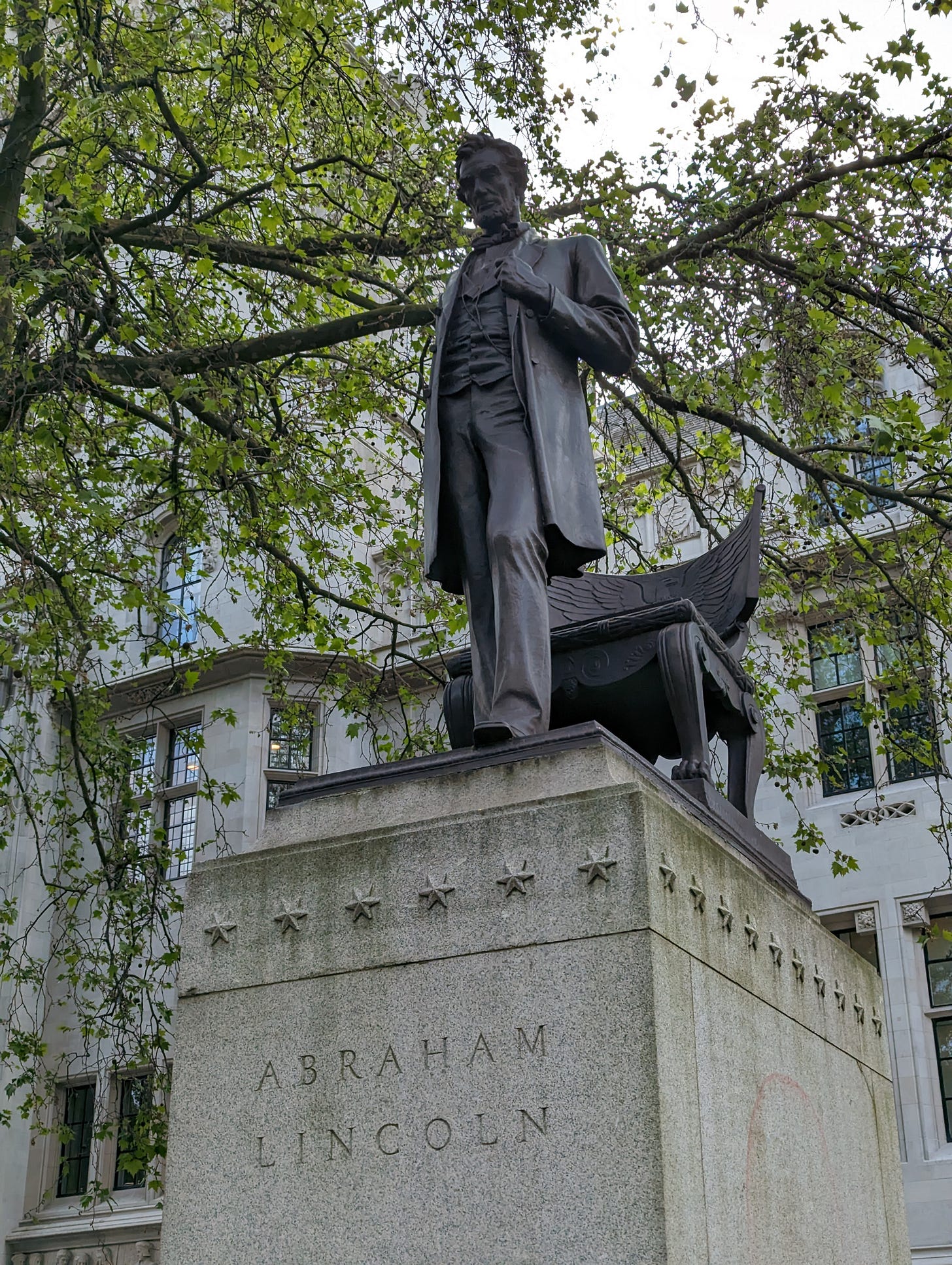

On Monday afternoon, we travelled down to London—our second visit in two weeks—where we stayed until we flew out on Friday. While there, we had the opportunity to catch up with several friends in a few different events and meet-ups. We set Thursday—Ascension Day—aside as a day to enjoy together. We spent much of it walking around London and enjoying the sunshine, visiting a variety of different places.

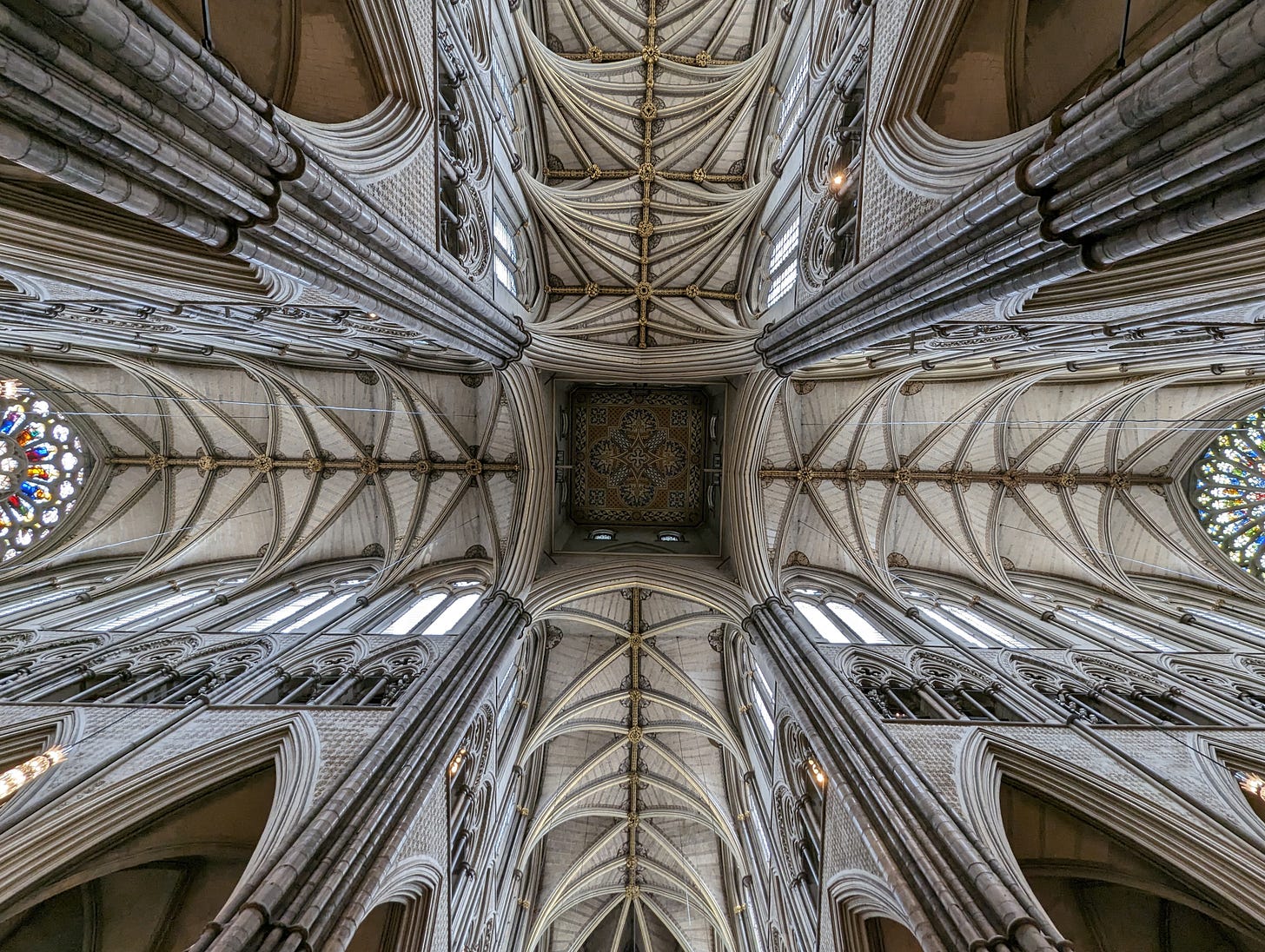

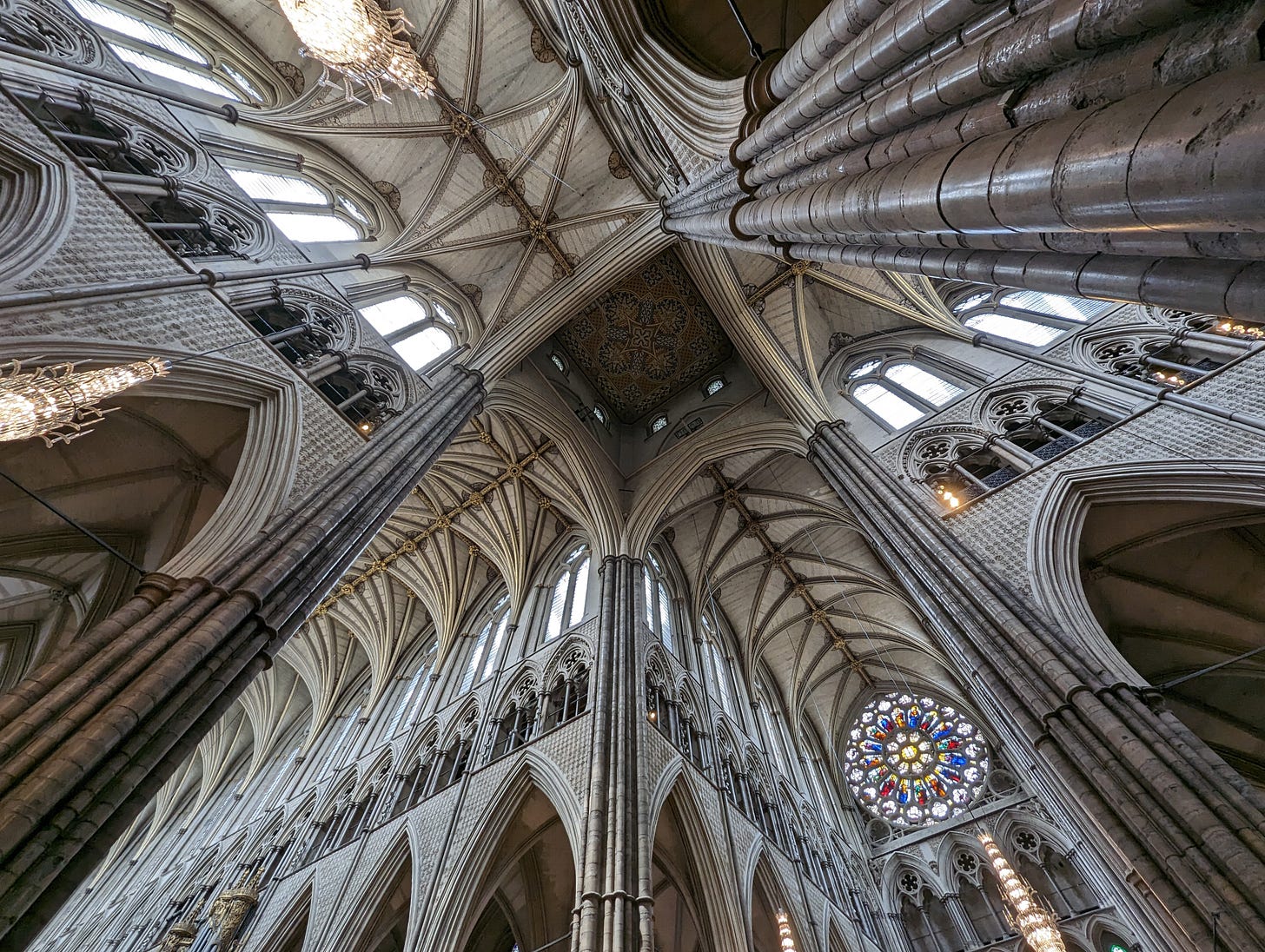

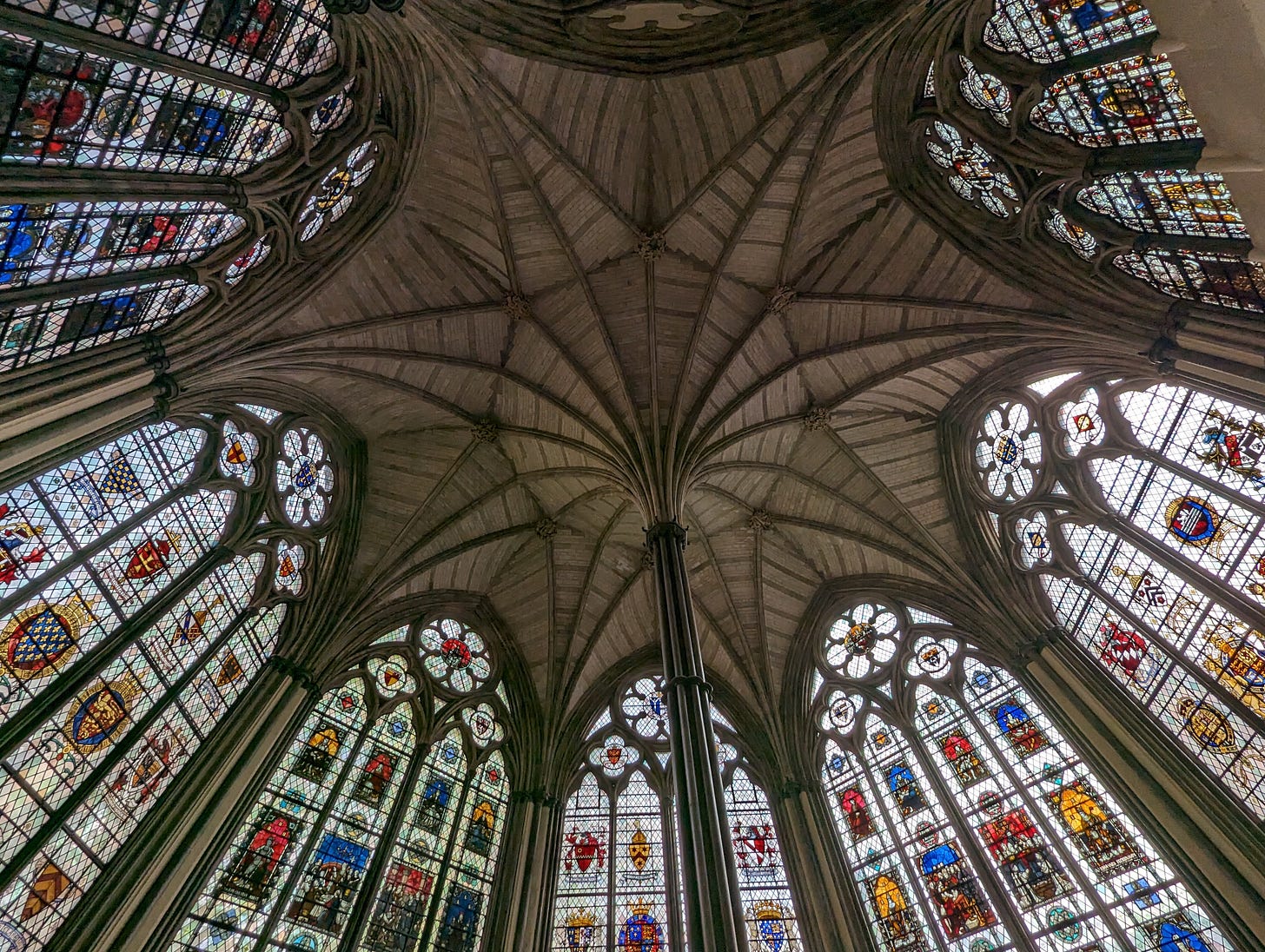

The most memorable part of the day was visiting Westminster Abbey, where we attended a communion service. We have some more thoughts on that experience below. We both had work to do, so we had to stop in the mid-afternoon and work for the rest of the day, but it was a glorious way to pass our last day of this stint in the UK.

After flying back to New York, we had to hit the ground running. The last few days have also been full of lots of work, events, meetings, and other things. Everyone seems to be getting married now: it is very exciting! We have had two engagement parties this week and have three weddings in the next several months, with a fourth that Susannah will be attending on both our behalves in October.

As we are on the road so much nowadays, we must also make the most of the brief windows of time that we have to reconnect as much as possible with our friends, family, colleagues, collaborators, and church. On top of our work, this means we have a lot of social activities and events during our shorter time in New York on this trip. Susannah is enjoying this. Alastair is managing.

While in New York City, we attend Emmanuel Anglican Church. We were married by the rector of the church last year. Alastair became a member of the church this morning.

Our Forest Hills house, a house that has belonged to Susannah’s family for four generations now, has sadly been sold by the family, so we are also needing to move our New York home over the next month. The family value of the home on account of its long history is considerable and it is a wrench to leave it, but we are excited to settle in at our new place on the Upper West Side, a short walk from Central Park. This puts considerable extra pressure on Susannah over the next few weeks, as Alastair will be away at Davenant House for most of June and she will have to organize much of the move without him. Please pray that the move goes smoothly and isn’t too stressful.

Living Words in a Nation’s Tomb

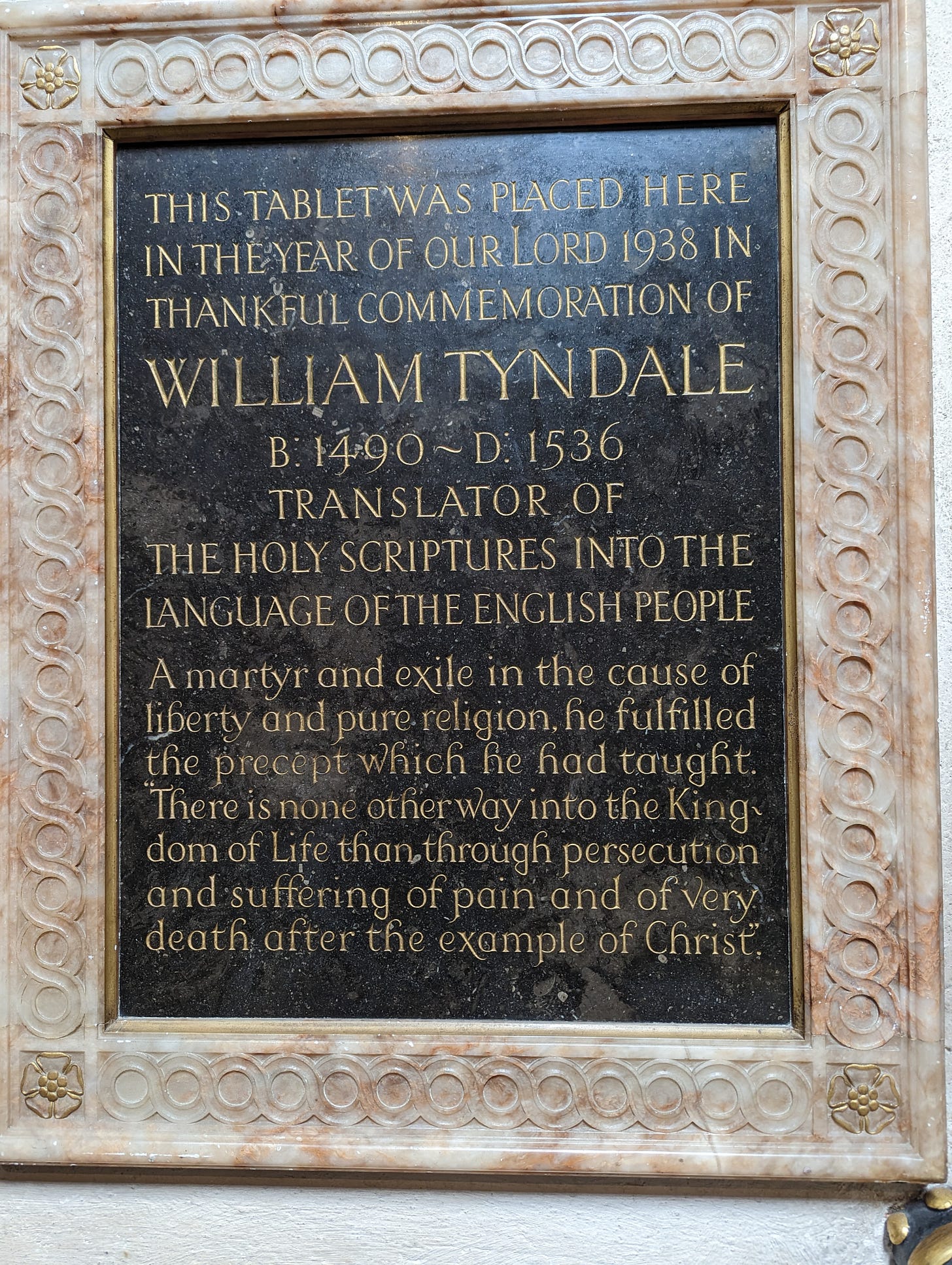

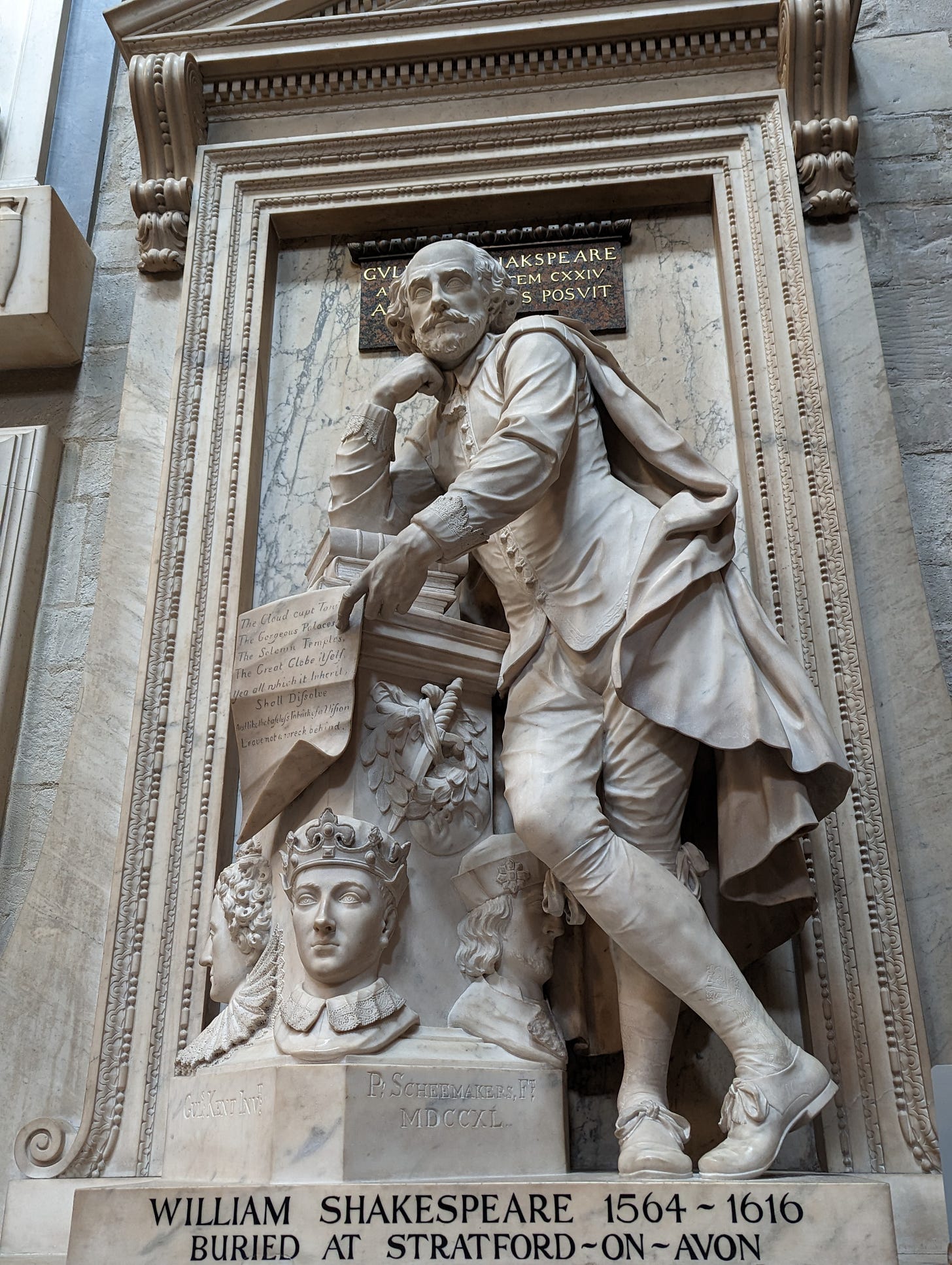

The controversial English historian David Starkey recently suggested that Anglicanism was a sort of British Shinto, in which the English worship themselves, a worthy object of such reverence in his estimation as a nationalistic atheist. Touring Westminster Abbey, as we did on Ascension Day, one could certainly see how someone might get such an impression.

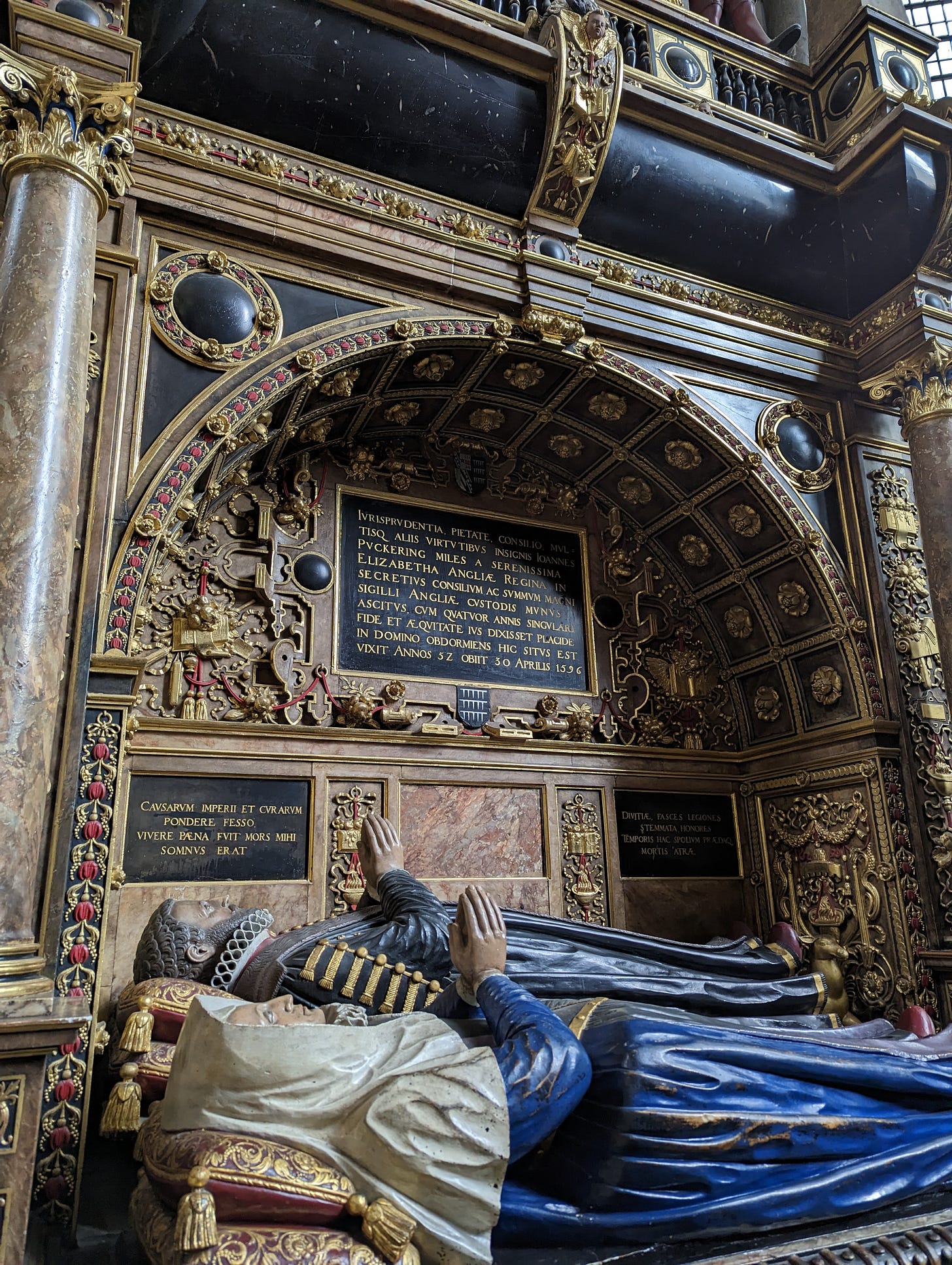

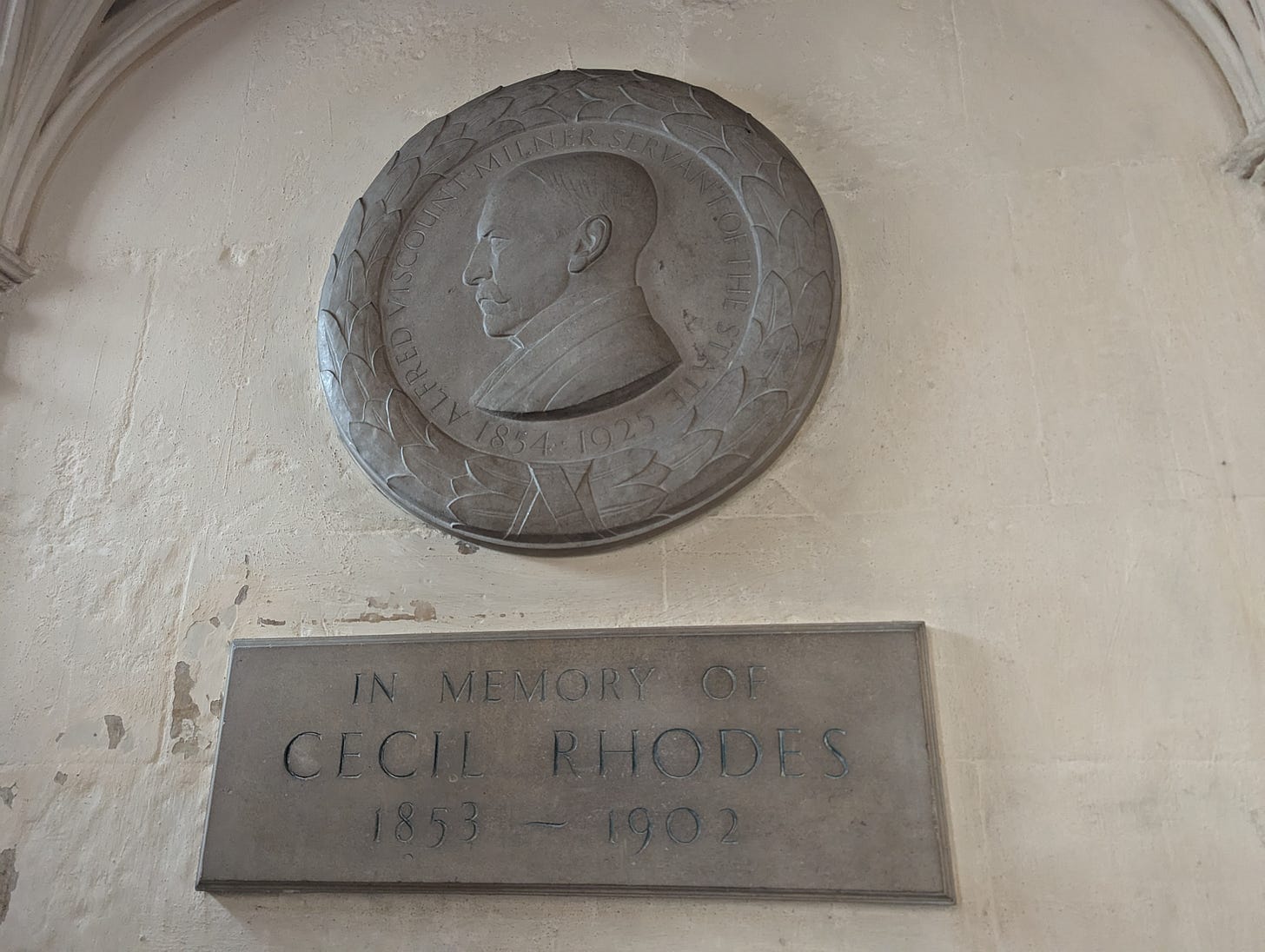

The Abbey, architecturally glorious and filled with magnificent memorials to the luminaries of numerous fields of endeavour in British history, can easily seem like a nationalist pantheon, elevation to which has always depended chiefly upon and served the burnishing of the nation’s glory, rather than God’s. Indeed, many of those memorialized within it are now more infamous than honoured, having once attained to power and prominence, yet known for their shameful deeds.

We should not miss the degree to which the Abbey opens itself up to and even invites such an interpretation. A church so wedded to the nation and its cause is always in danger of becoming the centre of an idolatrous cult of nationalism, reducing the Triune God to some tribal deity. So it has often been in the Church of England, perhaps most notably in our capital’s royal church.

Such a danger, however, existed even in the Temple which the Lord himself appointed. The Lord did in fact ‘wed’ himself to Israel. Nevertheless, the Scriptures, especially the prophetic books, make evident that this did not have the effect of reducing the Lord to a tribal deity, nor exempt Israel from judgment. Quite the opposite!

As we reflected upon all this while touring the Abbey, and catalysed by the Feast of the Ascension, a different perspective opened up to us.

People tend to consider Christianity’s place in a nation in more ideological categories: at some point in England’s past, for instance, most of the population believed, or were at least nominally committed to, the Christian faith. However, this can neglect the role that the Christian faith played at the foundation of the nation’s material existence and how central it has been to the national imaginary, preparing and producing the soil from which our focal symbols, stories, institutions, customs, laws, values, etc. have grown. Our very language would not be what it is were it not for the Scriptures.

As one example of the part that the Christian faith played in producing our material existence as a nation, the church played a critical role in marrying the British peoples to their land. Without minster communities, pilgrim ways, parishes and dioceses, parish churches as local landmarks, grand cathedrals that serve as the focal buildings of our cities (historically, city status depended upon diocesan cathedrals), churchyards connecting us with our forebears, the marriage of the English and the land of England would be quite different.

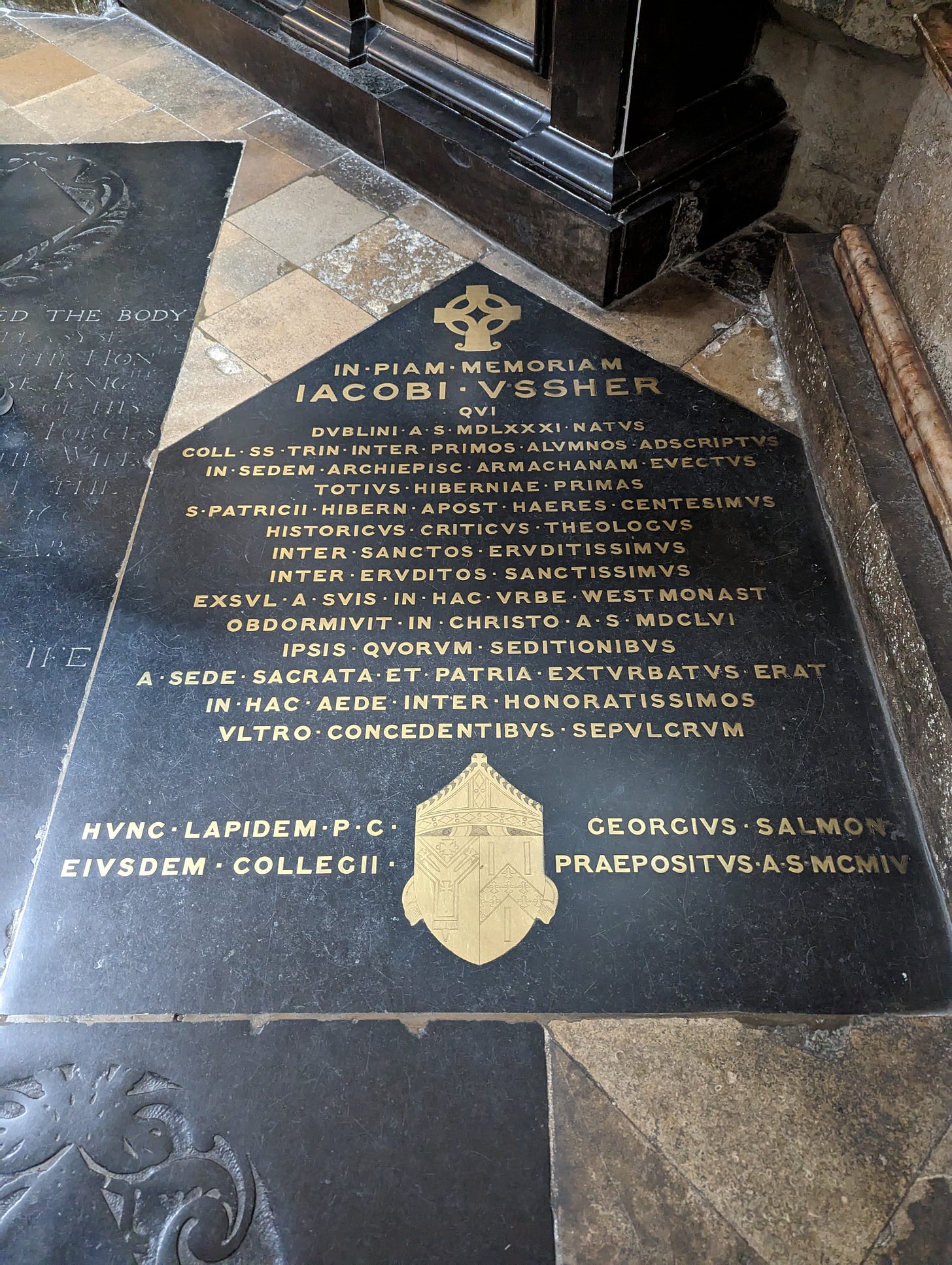

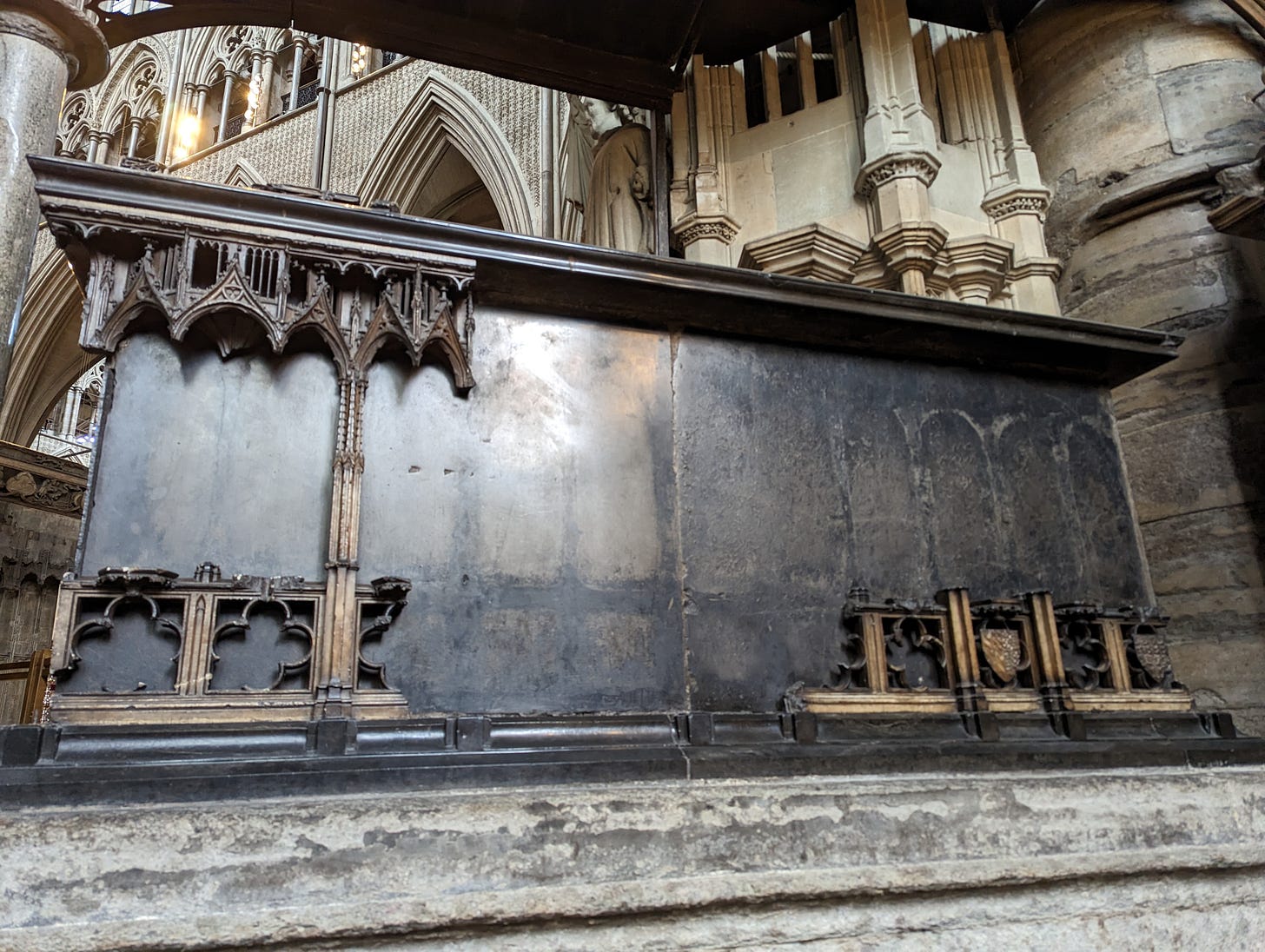

As moderns, we tend to think of our nations in abstract political and ideological terms. We talk about ‘the right’ and ‘the left’, about ‘democracy’, ‘freedom’, ‘sovereignty’, and the like. We can easily be dulled to the deeper material, imaginary, and mythic dimensions of nationhood. Yet in a building like Westminster Abbey, these dimensions of the nation’s existence are quite tangible. While village churchyards may contain the weather-worn graves of long forgotten individuals, Westminster Abbey is filled with memorials and tombs of the most famous figures of British history. Walking through it, it felt like the nation’s tomb, the bones and memories of the heroes (and not a few villains) of many past generations surrounding us.

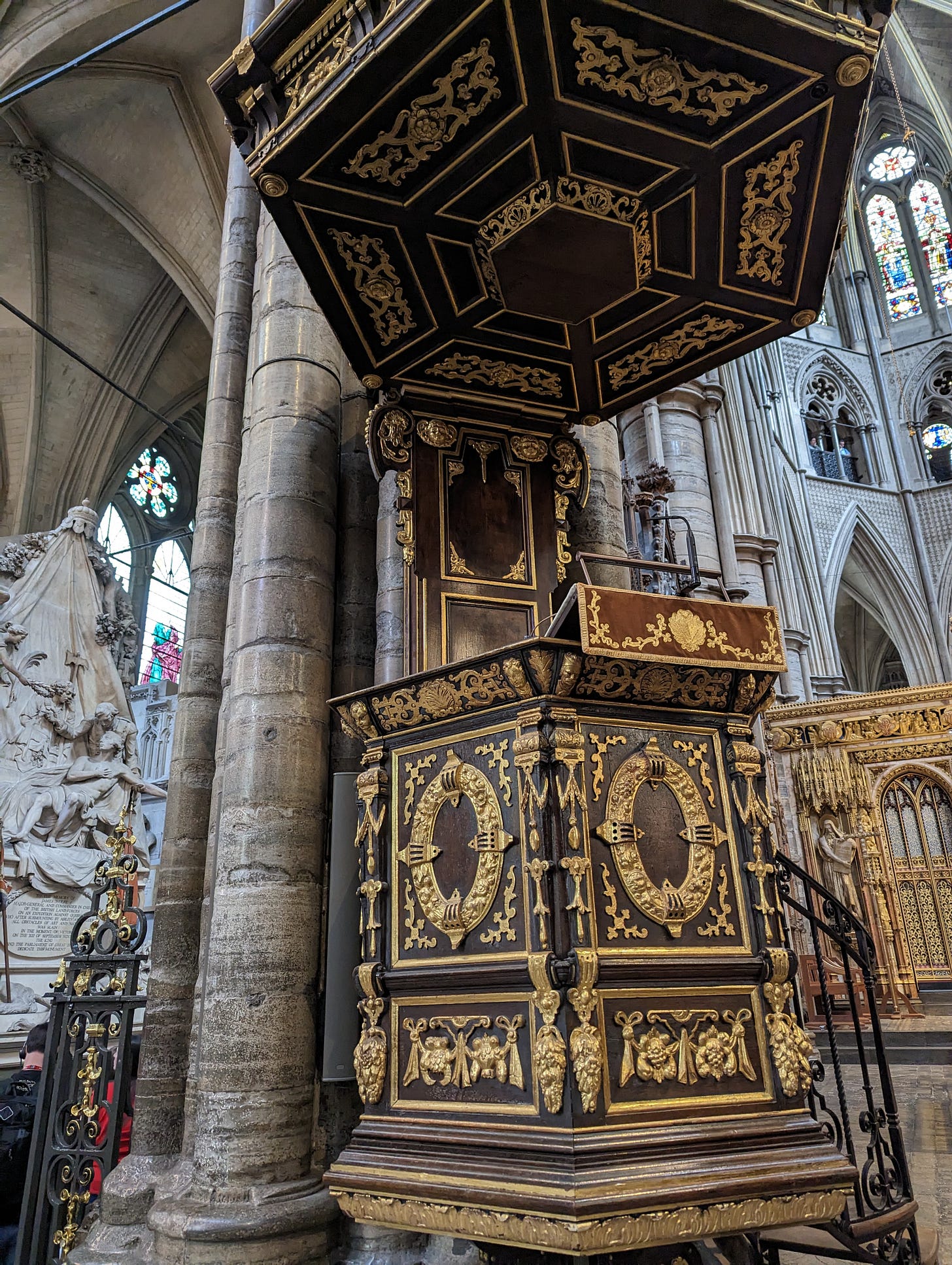

And it was through this recognition that the different perspective I mentioned above started to come into focus. The church is described as a building formed of people in several places in the New Testament. It is ‘built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets’ (Ephesians 2:20), the names of the apostles being written on its foundations (Revelation 21:14). Christians are described as ‘living stones’ within this building (1 Peter 2:4-5). In 1 Corinthians 3, the Apostle Paul speaks of the church as ‘God’s building’ (verse 9), going on to describe our labours as various forms of construction upon the foundation laid in Christ. All such construction will be tested and its character made manifest on the Day of Judgment—‘revealed by fire’ (verses 10-15). Considered from such a perspective, Westminster Abbey is a physical manifestation of Britain as a nation that has professed to be Christian.

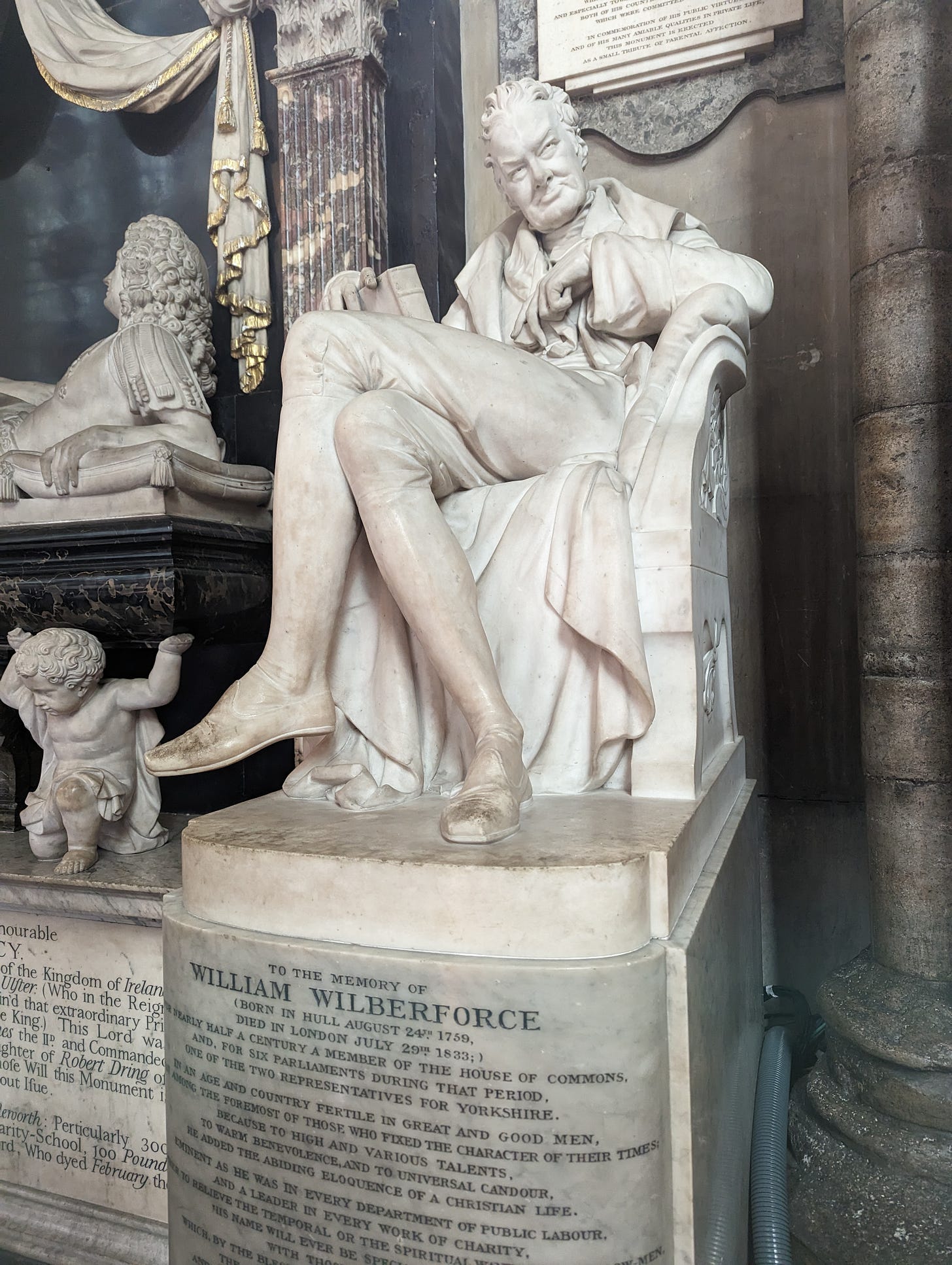

As a building full of tombs and memorials, in the Abbey it is the presence of the great gathered dead of the British peoples that one experiences. They have been stripped of their strength, authority, and glory. Kings and queens, warriors, poets, geniuses, explorers now lie in solemn rest, awaiting the Final Assize. And in the context of its life as a place of worship—and especially keenly on Ascension Day—one senses that our once glorious dead that have been buried and memorialized in this great royal church are thereby entrusted to the judgment of a higher King.

St Paul’s illustration of the great building to be revealed by fire comes to mind. Westminster Abbey is the edifice of the nation herself in architectural form, her dead heroes and her greatest children now encased in its stones, awaiting that final assessment. Walking through the Abbey, one feels the sobering weight of this. Doubtless much will be raised in glory—‘well done, good and faithful servant!’—but there will also be much weeping and gnashing of teeth—‘depart from me, I never knew you.’ The works of some may endure eternal, while the deeds of others will be consumed in a world-cleansing fire.

In Ecclesiastes 7:1-2 we read:

A good name is better than precious ointment, and the day of death than the day of birth. It is better to go to the house of mourning than to go to the house of feasting, for this is the end of all mankind, and the living will lay it to heart.

The Abbey is a such a place, where the nation is considered from the vantage point of its end. Within it we reflect upon what great persons have left behind, upon names and reputations, upon what has been lost and what has remained. Within it we reflect upon our own mortality and upon the legacy that we want to leave. Within it we feel the weight of brief lives in the face of eternity. Within it the bones of Britain rest, in hope of the final resurrection and placed under the holy judgment of a higher and undying Kingdom. Seen in such a way, the building discloses the truth of all our grand human endeavours. This is a truth not seen chiefly in the spectacles of our living pomp and power, but to be revealed in the awaited sentence of our Creator, to whose life-giving hands we must humbly entrust ourselves and all our works.

Worshipping in Westminster on Ascension Day, one feels more keenly the fact that the meaning of the place is discovered in the juxtaposition it physically sustains between its entombed monarchs and the continuing worship of the Lord and Giver of Life, the eternal King of kings. Death and life, mortal and immortal, temporary and eternal, earthly and heavenly: the Abbey holds together these realities, inviting us to discover the truth of our lives and nation in the Christian relationship between them.

Christians still worship in this church, serving the risen and ascended Lord. The Christian faith that played such a crucial role in forming the nation is still a living presence within it. The prophet Ezekiel, in a passage often read at Pentecost, describes a vision of the lifeless remains of his conquered nation, dry and sun-bleached bones littering a wilderness valley. God instructs the prophet to prophesy to the bones and the breath of the Spirit enters the bones and causes them to rise as a great army. In Westminster Abbey, the life-giving words of the ascended Lord are declared amidst the nation’s dead bones. The Spirit of Pentecost might enter them still.

Recent Work

Alastair

❧ A piece of mine was published in the latest edition of Plough: ‘In Praise of Costly Magnificence’. Within the article, I consider the significance of Mary of Bethany’s anointing of Jesus and some of what it might have to teach us about our relationship to wealth.

Jesus’ celebration of Mary’s act might puzzle us. Putting to one side his motives as a thief, surely Judas’ protest was justified: Mary’s anointing of Jesus with the costly perfume was a wasteful act, imprudent, extravagant, even luxurious. The money should have been given to the poor instead. This, however, is to miss the animating heart of Jesus’ teaching, which was never chiefly the negative character of wealth, the injustice of economic inequality, our need to divest ourselves of our wealth, and to redistribute to the poor. Such beliefs can all too easily be driven by a spirit of envy and ressentiment, no less under the thrall of money and its kingdom of values. Judas had never escaped this, as his judgment of Mary’s action reveals.

What Mary sees, that Judas and the disciples miss, is that our attitude to money must be guided by – simply is shaped by, if we are perceiving the world aright – love’s recognition of the all-surpassing worth of the kingdom of God, and the One in whom it is present in person. The danger of money lies in the ways love of it can seduce our hearts from the One who exceeds all else in value. Recognizing this, much of the New Testament teaching concerning money should fall into place.

Read the whole piece here.

❧ My friend Joseph Minich is the author of a recently published book, Bulwarks of Unbelief: Atheism and Divine Absence in a Secular Age. I wrote a blurb for the book, which I have raved about to many, describing it as ‘a wonderfully scintillating treatment of the spiritual condition of modernity, culturally perceptive and psychologically astute.’ Joseph joined me for a discussion of the book in a recent podcast. Our discussion ranged from the subject of Thomas Aquinas’s Five Ways to the spiritual threat of AI.

❧ Hans Boersma, author of the recent Lexham Press book Pierced by Love: Divine Reading with the Christian Tradition, joined Derek, Matt, and me on Mere Fidelity to discuss the historic Christian practice of lectio divina. You can listen to the episode here.

❧ Although I had to miss one of the recording sessions during my travels last week, the Theopolis Podcast series on Deuteronomy continues. I participated in the episode on the Greatest Commandment (5:22—6:25) and, in my absence, the guys recorded two episodes on chapter 7 with Ralph Smith as a guest (A Chosen People and The Lord Will Repay).

Upcoming Events

❧ We will be travelling to Davenant House in South Carolina this Tuesday and Wednesday. Alastair will be there for most of June.

❧ Most of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Susannah and Alastair

Really appreciate these reflections, Alastair and Susannah. They encompass and refine a lot of the questions that my students raise as we study British history and literature,; 'm going to be referring back to these thoughts in the future.

Susannah, I see what you did there (abandoning the NRx acronym and spelling out "Neoreactionaries").

BTW, you should read this related post by the music critic Ted Gioia (also here on Substack) concerning Alvin Toffler's "Future Shock", though that particular historical folly happened in the 1970's, not the 1870's... https://tedgioia.substack.com/p/in-1970-alvin-toffler-predicted-the