Alastair [Sunday, September 8th]: The weeks since our previous Substack post have been spent settling back into the routines of our life in Stoke-on-Trent. We have continued our blackberry foraging, have taken some long cycle rides, and walked a lot. We have started compiling a long list of places in our area that we need to visit, some in walking distance, others a cycle ride away, and others longer outings by train or car. The weather is predictably changeable now, so when we have a nice day, we try to take advantage of it in some way.

Cycling along the canal is one of the most pleasant and relaxing ways to explore. You never exceed a leisurely pace and do not have to worry about navigating traffic. Stoke has two canals running through it—the Trent and Mersey and the Caldon canals. These canals meet in Etruria, a former site of Wedgwood pottery. Not far north of the city, the Trent and Mersey connects with the Macclesfield Canal.

Three weeks ago, Susannah expressed a desire to see some of the countryside surrounding Stoke. The idea of striking out from our house on foot or bicycle and getting into open fields or woods greatly appealed to her, so we took an afternoon and cycled along the Trent and Mersey until the southern entrance of Harecastle Tunnel. At the Harecastle Tunnel we joined the road and cycled from Tunstall to Kidsgrove, where the canal emerges from the northern entrance.

We cycled a few miles further along the canal on the further side, before returning the way that we came. On the way back we dropped by my parents’ house, spending a short time with them before heading home.

On Friday 23rd, we decided to visit Alsager Book Emporium again. We had a local friend with us who had never visited the bookstore, so we wanted to introduce her. As the weather was glorious, I suggested that we visit Mow Cop first. Mow Cop is a village on the border between Staffordshire (our county) and Cheshire. It was the birthplace of the Primitive Methodist movement in 1800 and Mow Cop became famous for huge camp meetings.

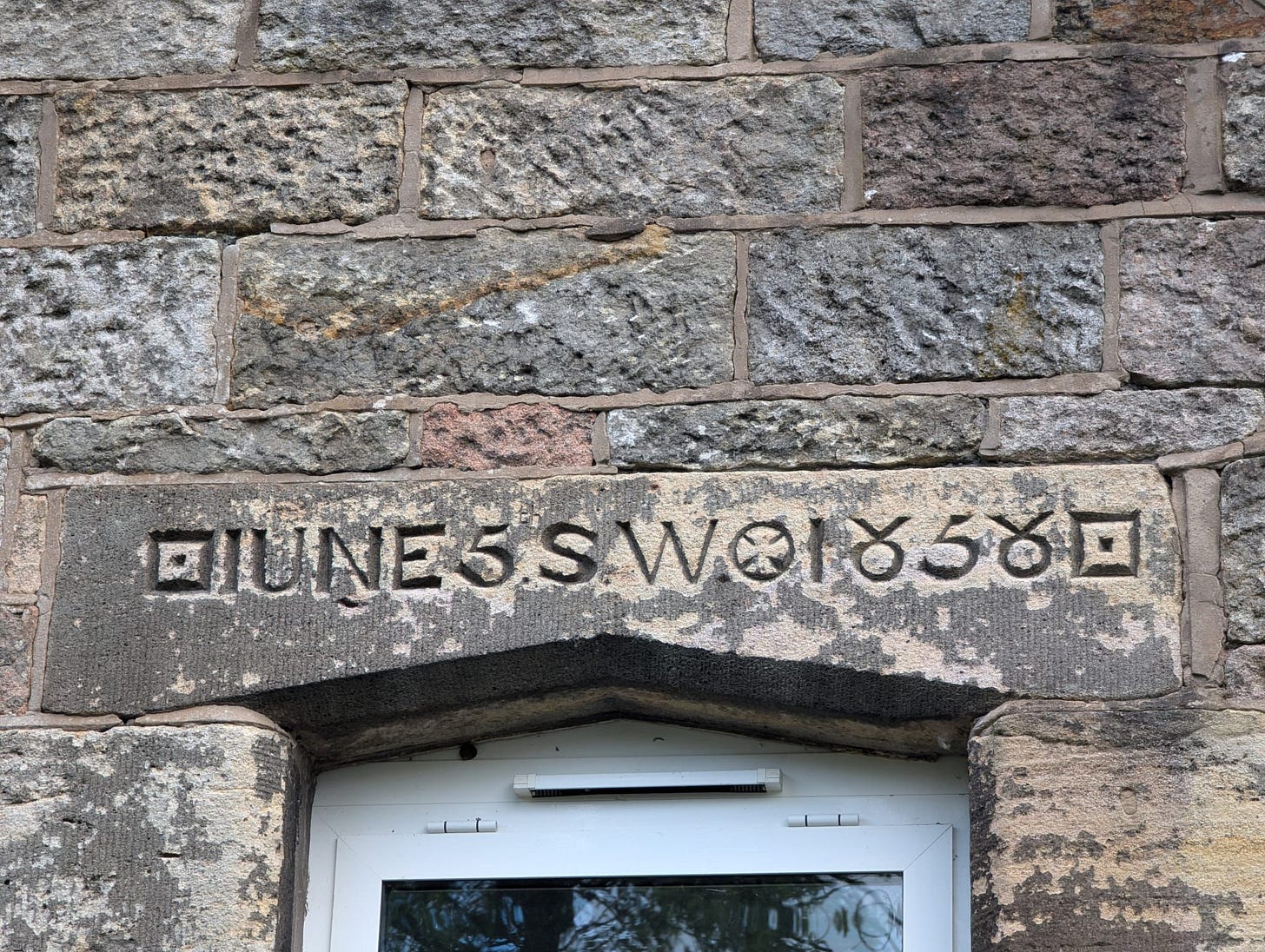

The village is situated on a steep hill, near the start of the Pennines and the views from the summit are spectacular. On the ascent, we noticed several straw people, apparently part of the Mow Cop Scarecrow Festival, an event of recent vintage. [Susannah: He says that, but does he really know? At the time we were basically certain that we had run into a village which had never fully let go of paganism and the straw figures had some ritual significance. We spent a lot of time attempting to figure out what this might be. We also came across this inscription, which did little to discourage the notion that the people of Mow Cop Village are up to something eldritch.]

Alastair: The route up to the summit of the hill is famous among local runners and cyclists as the Killer Mile.

At the summit of the hill stands Mow Cop Castle, a picturesque folly, dating from the mid-eighteenth century. It was Susannah’s first time seeing it, and it could not have been a better day. It was exceedingly windy at the summit of Mow Cop, as it has been on almost every occasion I have visited. However, the gentle fields, villages, and towns of Cheshire and Staffordshire that stretched out to the horizon on all sides were bathed in sunshine. Standing on some of the rocks against the wind and looking out over the vista was invigorating and exhilarating.

We had hoped to get an Uber from Mow Cop to the bookstore, but mobile connection was patchy and Uber service was limited. After one Uber fell through, Susannah suggested that we walk towards the bookstore for a while instead. Walking down the steep Mow Cop streets and out into the countryside was a pleasant prospect, so we did so. We ended up walking for over an hour, before we stopped at a pub for drinks near Kidsgrove and ordered an Uber for the rest of the distance.

The next day, Susannah and I walked from our house, through Hanley Park, along the Caldon Canal, and out to some fields fairly nearby. Susannah’s discovery that we can walk out our front door and, within under an hour, be standing in open fields has give her a new sense of power! [Susannah: This is so condescending.]

The Wednesday before last, we went over to my parents’ for a meal. Having them so close really is a great blessing.

One of the elders in our church is retiring, having served for over twenty years in the role, for much of it during my father’s ministry as pastor of the church. He invited Susannah and me to join him and his wife for a walk in Biddulph Grange Garden, which we had visited for the first time earlier this year.

It was an opportunity, among other things, to see the garden’s Dahlia Walk in its full splendour. Once again, we had marvellous weather, and were able to see the garden in a different season.

We ended the visit with drinks and cake from the tearoom, followed by some time in the second-hand bookstore, where I picked up some fantastic books at a bargain price.

Our godson was on a trip with his scouting group in Ireland, so his mother needed to collect him and some others from his troop from the ferry in Holyhead. As the drive from Durham to Holyhead is a long one, we invited them to split the journey in Stoke, staying with us overnight.

After they arrived, we walked along the canal and had a carvery meal, a new cultural experience for Susannah. A carvery is typically a restaurant which offers large Sunday roast style meals in a buffet form at a (generally very cheap) fixed price. Susannah also tasted sticky toffee pudding for the first time.

The next day we drove to Llandudno, a north Welsh seaside town, sharing the trip with my favourite spaniel, who was very excited to see me again. I used to walk him several times a week, and we both miss each other a lot. The day was overcast and we started by walking along the promenade, before driving up to the top of the Great Orme, the headland that overlooks the town.

[Susannah: Llandudno has, among other things, a restaurant advertising a “supper club,” and a “discotheque” - it is a place that is aggressively resisting any attempt to pull it out of 1973, and I respect that. It also has a Punch and Judy show.]

Both trams and a cable car run to the top of the Orme, which, when the weather is good, affords stunning views over Llandudno and the other nearby coastal towns. Unfortunately, although the rain held off for a while, enabling us to have a short walk, the heavens soon opened and we had to return to take shelter in the summit building. The short walk we enjoyed, however, did give us time to see the famous Llandudno Kashmiri goats, even if the inclement weather did limit the views.

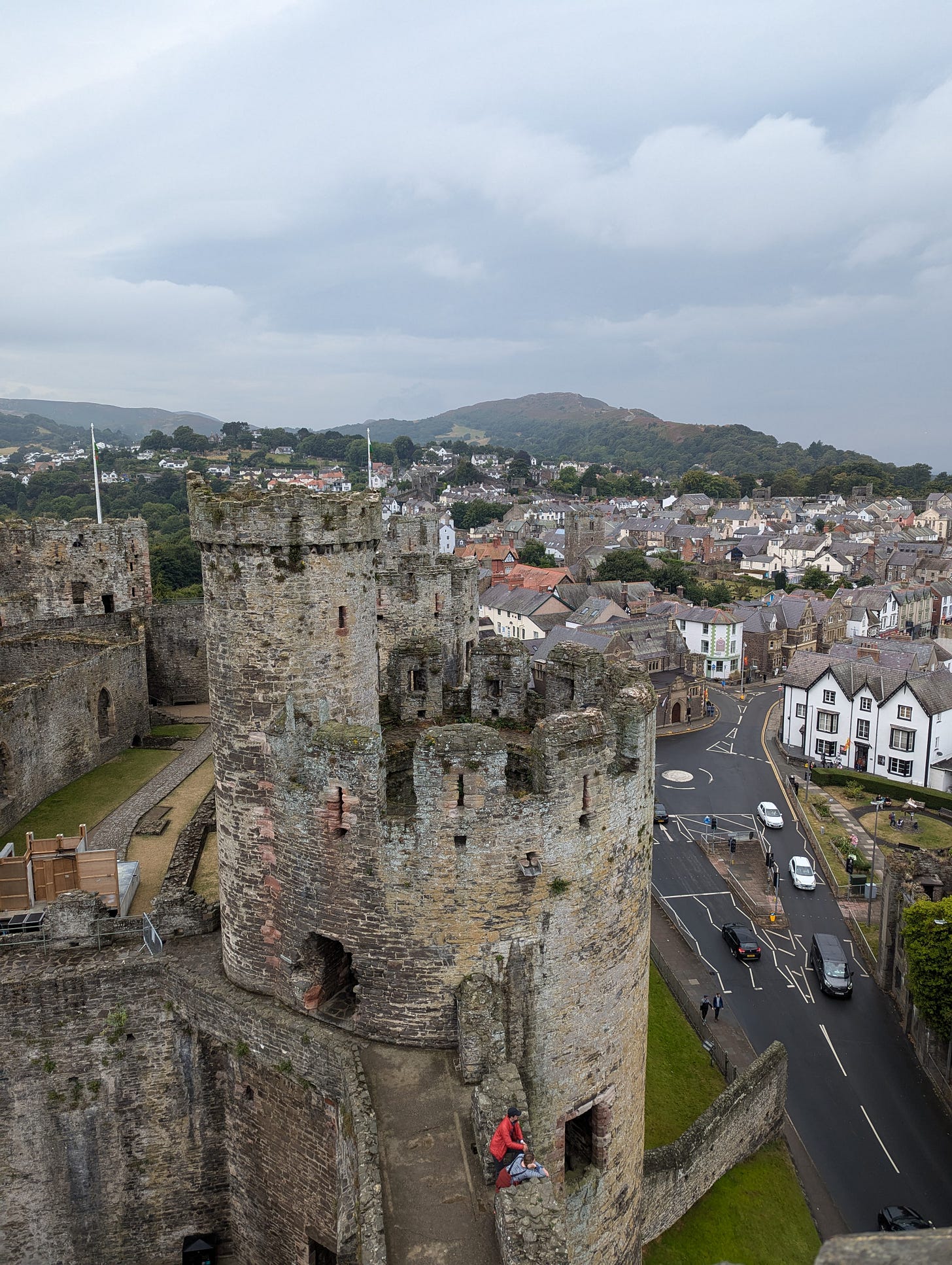

From Llandudno we drove to Conwy, on the other side of the headland. Although I had visited Conwy and its castle with my brother and his family in December, Susannah had not been able to join us on that occasion, and was bitterly disappointed when she saw what she had missed out on.

We had a meal together in a pub and, because the dog was not allowed into the castle, [Susannah: This seems disgraceful to me. What’s a castle without a dog?] Susannah and I went in by ourselves. Although it remained overcast, the rain had largely stopped and we were able to see much of the castle together, climbing a couple of the towers, from which we were able to look out over the bay.

The castle, along with all the fortifications of the walled town of Conwy, was built by Edward I between 1283 and 1287, a truly remarkable achievement, although probably benefiting from laxer planning regulations. The castle saw combat at several points in its history, even being occupied by Owain Glyndŵr’s forces for several months in 1401.

Susannah was overwhelmed by the castle, its scale, and its setting, with its commanding views of the bay. Our time was limited, as we needed to meet up with our friends again, but we were able to see most of the castle.

Our friends were going to travel on to Holyhead, but they dropped us off at the station at Colwyn Bay before continuing their journey. Our train journey back was a rather lengthy one, involving changes at Chester and Crewe, where we were supposed to catch a rail replacement bus. While on the train, I suggested to Susannah that we take advantage of our open tickets from Chester and spend an hour in the city.

[Susannah: Please note the Victorian medievalist guild socialism implied by the mottoes below.]

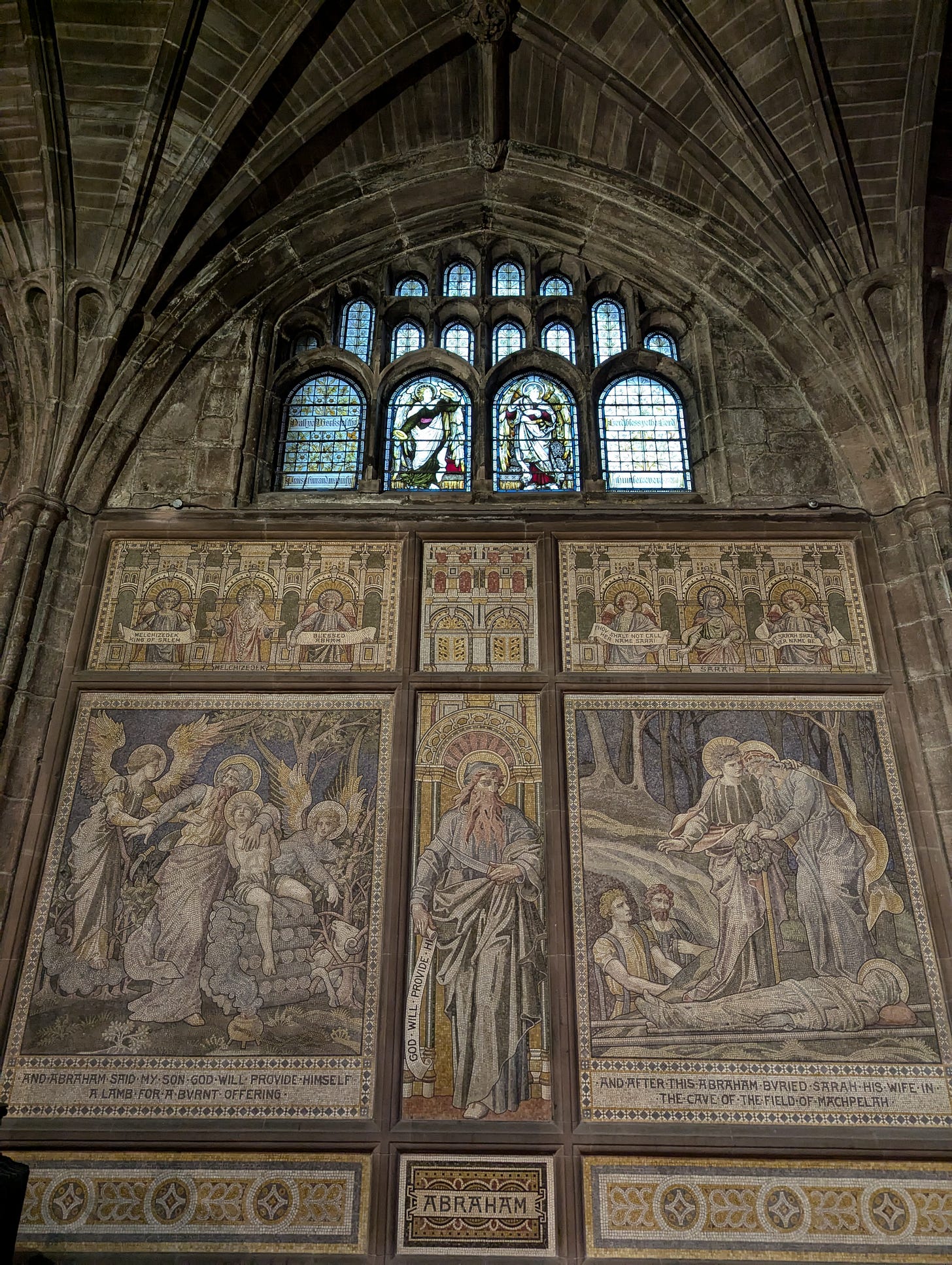

I had not visited Chester for a few years and Susannah had never seen it. It is a charming city, with a modest cathedral and some charming Tudor-style architecture, much of it Victorian in origin.

From the train station we walked to the cathedral, arriving at the end of a service, before wandering back. We saw the famous Eastgate clock and Susannah was able to get a sense of the city, whetting her appetite to visit it again. It is only an hour away, so doubtless we will do so soon.

We have done quite a lot of walking over the past week in our area. Susannah recently discovered some fields behind Fenton Park and we walked out there on Friday, spending a couple of hours exploring.

As a polycentric city, Stoke-on-Trent is quite unusual. It is composed of six towns that were federated into the city in the early 1900s; listed from north to south, the six towns are Tunstall, Burslem, Hanley, Stoke-upon-Trent, Fenton, and Longton. Throughout the city are scattered suburbs, districts, and villages, many of them with their own very distinctive character and history (in some cases dating back over a millennium), places like Etruria, Trentham, and Middleport, among several others. The novelist Arnold Bennett set many of his novels and short stories—most famously, Anna of the Five Towns—in a fictionalized version of Stoke-on-Trent, from which he excluded Fenton.

While Hanley is typically regarded as the principal hub of the city, we seldom have occasion to go into it. There are also several nearby towns that merge into Stoke as part of a larger conurbation. Some of these have come up in this and previous posts, places like Biddulph, Alsager, and Kidsgrove.

It is currently Heritage Open Days in England, a festival of culture and history, during which many events and attractions have free entry to visitors. We decided to take advantage of the opportunity yesterday and saw three different places: Gladstone Pottery Museum, Etruria Bone and Flint Mill, and Our Lady of the Angels and St Peter in Chains church.

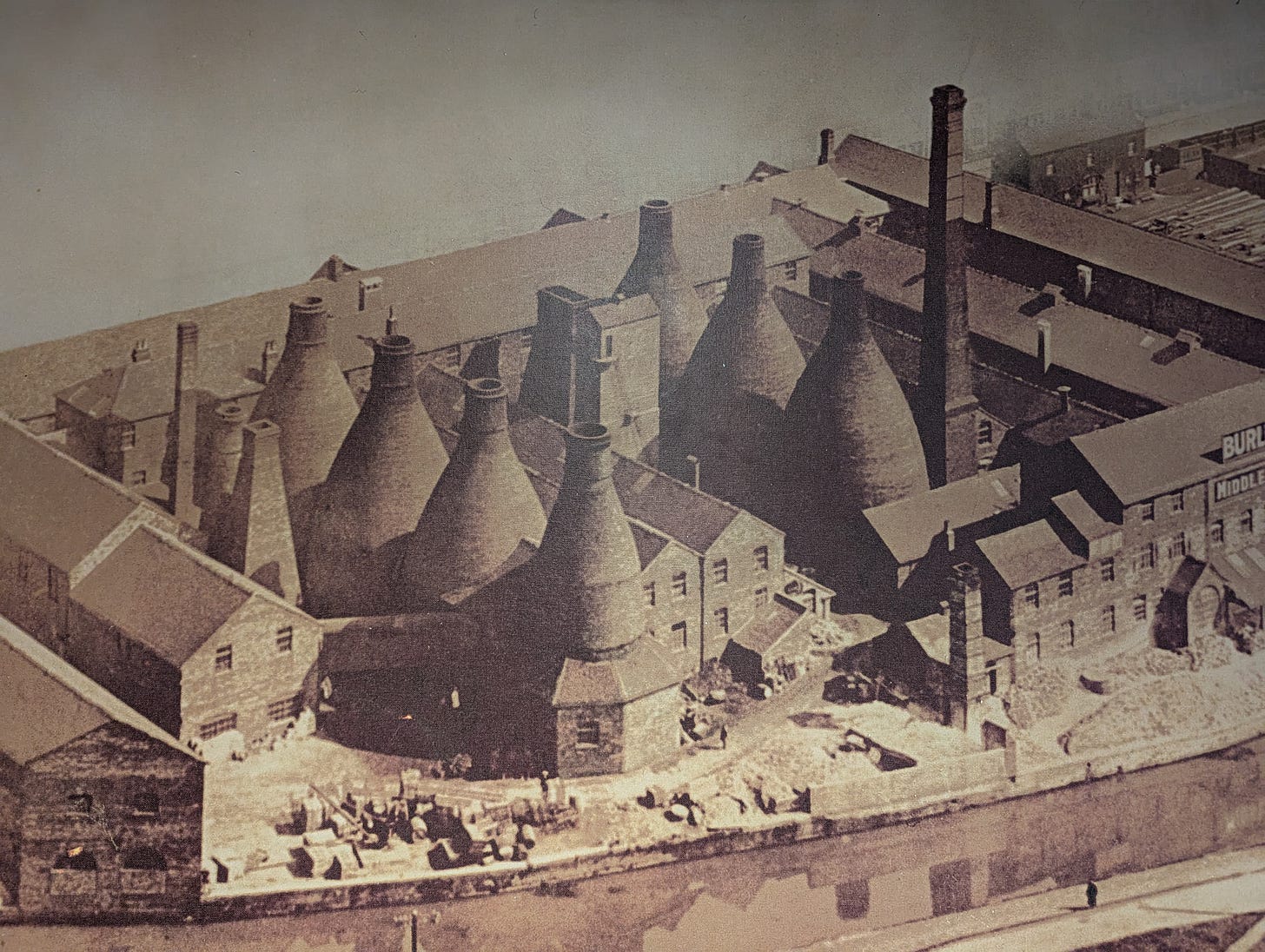

Gladstone Pottery Museum is a small former pottery, dating back to the late eighteenth century. It received a last minute reprieve from demolition in 1970, being transformed into a heritage museum. Although not famous like larger Stoke-on-Trent pottery manufacturers such as Wedgwood, Royal Doulton, Spode, or Minton, Gladstone is one of the only surviving examples of the potteries that used to fill Stoke-on-Trent. There used to be over four thousand bottle kilns in Stoke in the heyday of the local pottery industry, yet under fifty remain.

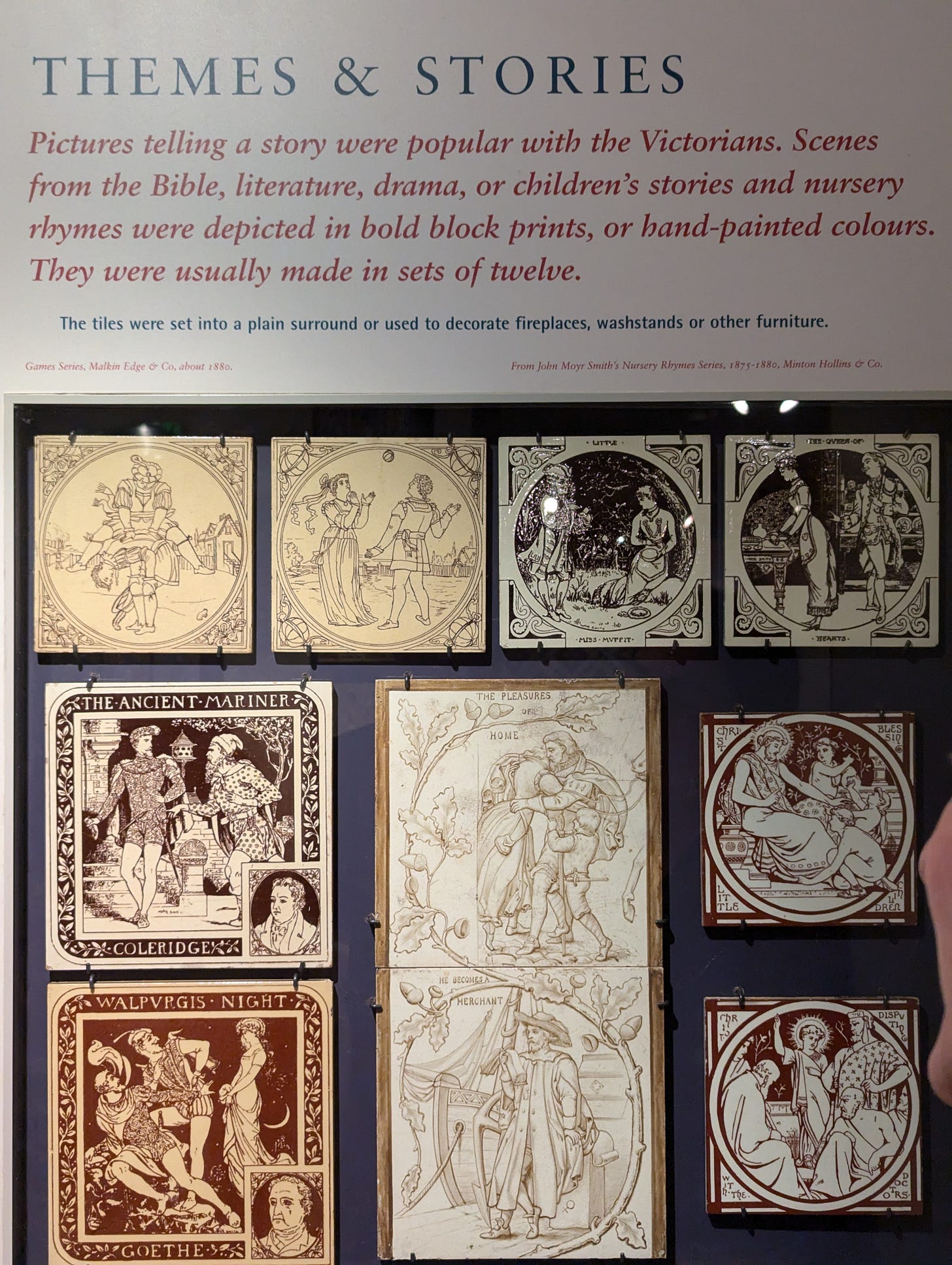

The museum guides you through the entire production process, it has exhibits devoted to aspects of the life of the pottery workers, and sections devoted to the history of tile design and of toilets. As a centre of the ceramics industry, the Potteries—and notable figures like Henry Doulton—were also pioneering developers of the toilets, sinks, and pipes that propelled the sanitary revolution.

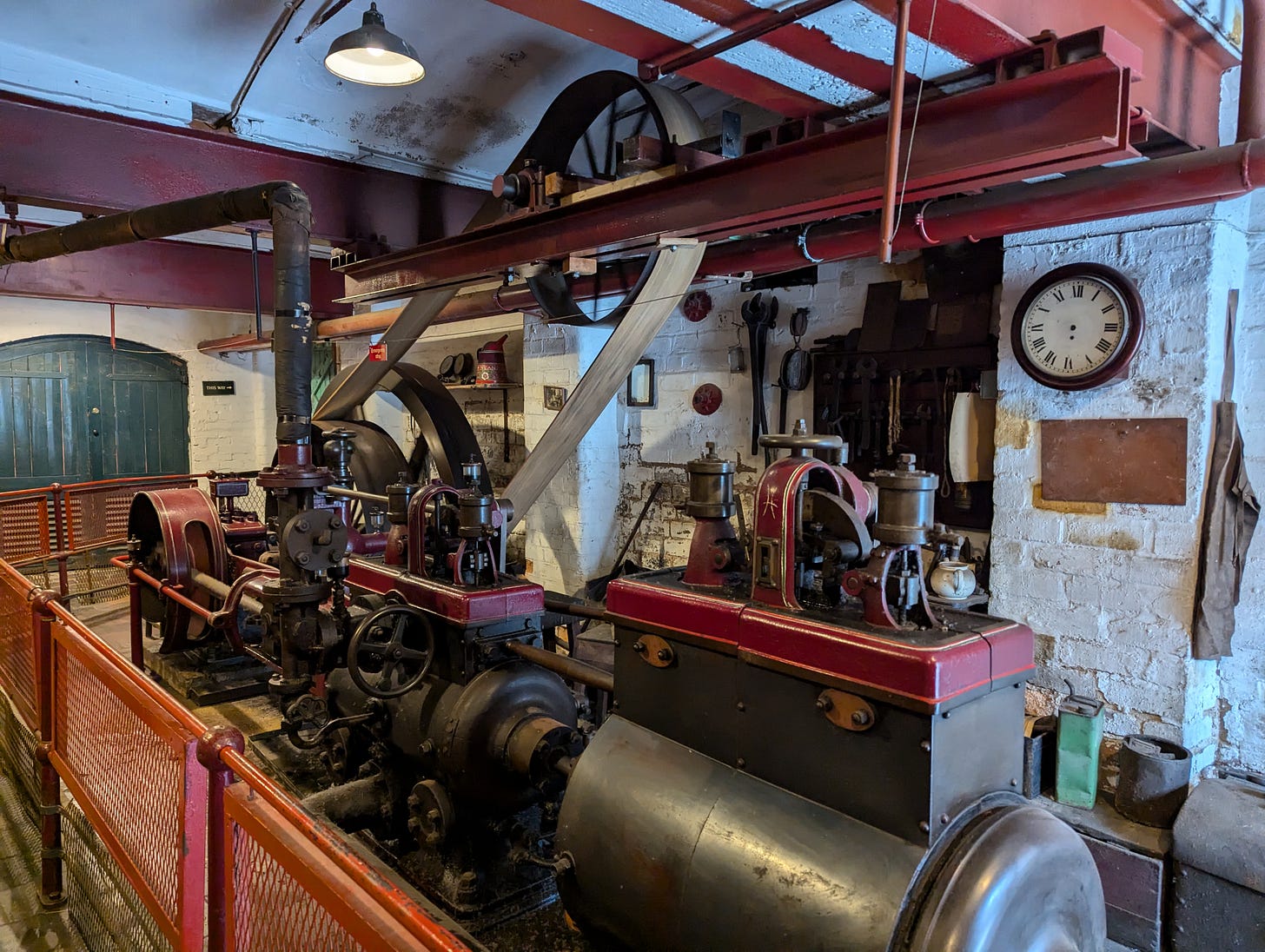

From Gladstone we went to the Etruria Bone and Flint Mill, which we frequently pass when walking or cycling along the canal, but had never visited. The mill used a steam engine to power machines to grind flint and bone for use in pottery manufacture—the flint for strengthening the pottery and the bone for the making of bone china. The mill, which was in continuous use from the 1850s until the early 1970s, has since been restored and is operated by volunteers, who demonstrate the machines to visitors.

The gear room

The pan room

The engine room

Outside the museum, alongside the canal, they had an exhibition of historic engines, and a demonstration of blacksmithing in the old Etruria forge. Etruria was the world’s first industrial village, the site of the old Wedgwood works, and of Thomas Wedgwood’s innovations in early photography.

We concluded the afternoon by visiting Our Lady of the Angels and St Peter in Chains church.

Alastair [Wednesday, September 18th]: This Substack post is quite overdue, but we continue to have very full lives! The highlight of the past week was a visit from some dear friends from Long Island over the weekend. We were able to introduce them to Stoke-on-Trent. We will be spending time with them again this weekend down in London.

They arrived in the mid-afternoon on Saturday, so we were limited in the time we had. We took an Uber out to World of Wedgwood, where we looked around its superb museum and then walked along the canal to the Plume of Feathers pub, where we shared a meal. The stretch of canal beyond Wedgwood is one of my favourites, especially in the low light of the early evening.

On Sunday, after church we visited Middleport Pottery, which was also free for Heritage Open Days. Middleport offers another window into what life and work in the Potteries was in the nineteenth century. Burleigh pottery is also some of the finest.

Middleport Pottery has a huge collection of plaster moulds and also a recreation of much of the interior of a house from the 1950s, an extension of the Heritage Trail in Harper Street.

The weather was inclement, but we went from there to Little Moreton Hall (which Susannah and I had visited in better weather in December). Little Moreton Hall is a completely chaotic yet charming Tudor building.

As the weather is colder and wetter now, we have been making more of an effort to take advantage of it when it is pleasant. On Monday, we were blessed with some glorious sunshine in the afternoon, so we decided to take an exploratory excursion further along the Caldon Canal, well beyond the place where we had left it on our previous visit.

We joined the canal at Hanley Park and followed it from there. Hanley Park is another beautiful spot near to us in Stoke.

The Caldon Canal is much quieter than the Trent and Mersey—we only saw a couple of barges on our trip. The canal is also narrower and the borders of the towpath more often overgrown. We did encounter a number of cyclists and pedestrians, though, so it is by no means unused.

We went out beyond Abbey Hulton, before returning by the same route, following the canal to Etruria, where it connects with the Trent and Mersey.

Life with a regular work routine, punctuated by walking and cycling along the extensive inland waterways of the West Midlands, is delightful. We feel enormously blessed to live here.

Keeping Faith In and Out of Politics

Few things can be more fraught and complicated than questions relating to the appropriate involvement of pastors, theologians, apologists, and other Christian scholars, journalists, and commentators in political action and discourse. Much of the complexity arises from the fact that so many applaud—or are, at the very least, highly indulgent of—strong appeals to the authority of Scripture and Christian principle on politically controverted issues, claims of ethical duty to specific political actions, policies, and voting decisions, condemnation of the evils of particular parties, politicians, and policies, and explicit or implicit party alignment or support for specific political candidates, provided that these come from pastors, theologians, and other Christian commentators who share their political priors and advance their political agendas.

Reliable principles are hard to come by in such a context, where most people have some interest in gerrymandering principles that legitimate their own political stances, policies, involvement, and associations, while delegitimating those of their opponents. Indeed, to many minds, such ‘principles’ are distractions and deflections from what really matters; the true issue is which side is advantaged. Appeals to ‘principles’ can provide a convenient mask of supposed objectivity and neutrality upon highly partial approaches. Deployed inconsistently, or with a lot of complicated qualifications, the smart casuist can use them to justify any approach they desire. Consequently, some can regard supposed ‘principled’ people with greater suspicion, preferring to deal with the open partisan, who is at least open in their prejudices and interests. Principles can seem much less important than the question of the side in whose favour they are being wielded.

Where such mistrust exists, a more consistent hermeneutic of suspicion may soon emerge, something to which the immediacy of online social media lends itself. Rather than expressing principle with candour, all speech impinging upon the realm of politics is judged and measured purely as political speech act, with the decisive criterion being cui bono?—which party in society benefits most from the speech acts in question? In such a context appeals to supposedly arbitrating principles are presumed to be cynical and dishonest. The actual, though typically dissembled, interests of the speaker are revealed as we strip away claims to objectivity, neutrality, impartiality, and truth, focusing upon where they are punching and where they are coddling—left or right? Where there is such an assumption that people are speaking and acting in bad faith, discourse will break down and mutual suspicion will take over. Importantly, the possibility that there might be motives beyond or exceeding merely partisan political ones is not truly accounted for.

The following are some initial and non-comprehensive considerations concerning the relationship between pastors (and, to a lesser extent, Christians in other vocations) and political speech.

At the outset, there are many senses in which we may speak of some action or statement being ‘political’; if we do not make some distinctions, overextension and equivocation in our use of the term may mean that we obscure more than we reveal. The failure to draw such distinctions flattens out forms of political action and engagement, causing problems in different directions. For instance, on the one hand, it can suggest that all political speech is similarly invested and entangled in the messy world of partisan politics, and that any appeals to principles that supposedly stand over this are cynical, deceptive, or naïve. This can produce an impatience with and resistance to moral criticism. On the other hand, where it insists on the existence of higher principles to which politics is accountable, it can leave little room for the difficult prudential deliberations and decisions of practical politics, reducing it to a sort of screen for sanctimonious morality plays, in which opposing attempts to signal the virtue of our own sides, beliefs, and motives and to demonize our rivals’ overwhelm everything else.

Peter Leithart and other self-styled ‘ecclesiocentrists’ have argued that the Church is the true polis, the ‘archetypal political community’, a model of how things really ought to be, a vision of how things really are, and a foretaste of how things are going to be. Churches, and the Church more generally, are a form of social organization that, in their very nature, cannot merely be consigned to the realm of private voluntary associations. However, Christians neither relate to the polities of this present age as revolutionaries nor as quietists who withdraw from engagement in their societies and governments. The message of the gospel is a message that is political in character—‘Jesus is Lord’—and calls for recognition and obedience from the rulers of this age, even though this definitely does not entail rule by the Church, nor clerics exercising a meddlesome role in practical government, nor the kind of theocracy that some might imagine.

Understood in this sense, the Christian message is inescapably ‘political’, even if this politics is not politics as we typically know it (which is not to say that it is ‘apolitical’ as we know that). While the Church and its message are not in direct competition with the rulers of this age, they present an unavoidable challenge and proclamation to which the rulers must respond. The preaching of the gospel must be ‘political’, and not merely by virtue of secondary ‘application’. Such ‘political’ speech from the pulpit, however, is not going to be as objectionable as straightforwardly partisan political speech—speech that aligns with a particular party against another on converted questions of government and policy—will be.

The equation of ‘politics’ with oppositional partisan politics—especially in polities like America, where politics is overwhelmingly partisan in form—might also obscure several of the ways that churches and ministers of the gospel might have a non-partisan involvement or investment in wider affairs of society and the ordering of its common life. Practically speaking, such non-partisan involvement and investment might include hosting public or national events, civic occasions, and activities relating to the common life of the polity, such as serving as a polling station, operating as a national church for occasions such as a coronation, hosting civic celebrations, or functioning as chaplains for political agencies.

In many contexts, both local and national, churches are deep and important elements and recognized trustees of aspects of the social fabric, perhaps expected to speak and act in a less partisan manner for the common good, for those most vulnerable in the case of its loss, such as the poor or homeless, and as voices of moral conscience in the society’s wider political deliberations. In rare cases, churches and their leaders may even have established representation in political bodies, as the Lords Spiritual do in the House of Lords. The latter is an instance of another sense ‘political’ involvement might have in some contexts: as direct speech to questions of government, even if not from a position aligned with any specific political party. For instance, the Lords Spiritual have previously spoken against and helped to defeat bills on assisted dying.

We could consider the possibility that the more complicated political agency of the Church might in certain limited respects be analogized to that of the king in British constitutional monarchy. The king is expected to be both politically neutral—neither publicly taking any partisan political stance nor voting—and politically active—not least in being consulted and providing counsel in a private weekly audience with the Prime Minister. Beyond the question of such activity, the king also serves as the symbol of British sovereignty, the elected government serving in his name, the currency bearing his image, the judiciary swearing allegiance to him, etc. Nevertheless, the exercise of government is the preserve of elected officials, not the monarch. The king also cannot merely represent one constituency of people within the nation, but must represent everyone, and the nation to them.

As an analogy for the role of ministers of the gospel, for instance, this might be a limited one, yet it does illustrate the existence of more complex forms of political agency (and even more so when one considers the role that the Church plays relative to the monarch and his authority). It also might serve to illustrate the way in which certain forms of authority can be jeopardized by partisan alignment, excessive attempts to influence government, or meddlesome involvement in questions of policy. Where the authority of the gospel gets aligned with the sectional interests that predominate among Christians in some context—treating ministers of the gospel as if they were chiefly representatives of some religious constituency or lobby—or with the interests of a specific party, or where ministers routinely wade into prudential policy questions or telling congregants how to vote, the proper authority of the Church can easily be compromised.

There are several other senses in which people might speak of churches or ministers being ‘political’. Pastors might highlight the vices and sins of prominent political figures, parties, or voters, in ways that seem more heavily to censure the behaviour of one ‘side’, leading them to be accused of being partisans of an opposing side, especially by those who do not recognize concerns that exceed the prevailing partisan politics. Typically, people are far more sensitive when it is their side being challenged, and ministers who routinely flatter the political prejudices of their congregants may face little criticism. As people might feel that things only really ‘get political’ when views that challenge the prevailing beliefs of their group are pressed or a position on a highly controverted question is taken, ministers are much more likely to be accused of being inappropriately political when countervailing some social or political consensus shared by their congregants then when reinforcing them.

[It should be noted that I am chiefly speaking about Christian ministers, although theirs is but one of several Christian vocations about which questions of appropriate political involvement might be asked, and to which differing answers ought to be given. Similar questions could be asked about theologians, Christian ethicists, Christian journalists and commentators, those involved in Christian charities, among others. From another angle, we can ask questions about the bearing of their faith and church membership upon the political activity of Christians involved in politics, from regular voters, to political theorists, to politicians, etc.]

Here it is important to consider diverse forms and contexts of speech and capacities in which people can speak. Not all pastoral speech, for instance, occurs from the pulpit, nor should it. While pastors should be extremely wary of venturing into prudential questions of government and policy, telling their hearers how to vote, aligning more broadly with one partisan camp, or speaking and acting in ways calculated to underwrite some class, ethnic, or tribal interests, such deliberative matters are important ones for which Christians need to be equipped.

The principles typically will not be abstract nor directly prescriptive, but are values, norms, and processes that enable and inform thoughtful, faithful, and imaginative concrete exercise of our political agency. Ideally, ministers should be able to teach congregants something about what responsible Christian deliberation about such matters looks like and some of the principles that have bearing upon it, while making clear that their teaching in such prudential matters is much more limited, fallible, and advisory in character, subject to many considerations beyond their competence, and certainly does not come with the force of a ‘thus saith the Lord’.

The teaching more especially entrusted to ministers also has considerable bearing upon the political action of their congregants, and pastors really need to provide guidance for congregants in societies where politics and its passions are so pervasive and powerful, with many being poisoned by them. However, such guidance will mostly be driving home basics that should ground and shape everything we do: pray for, honour, and submit to authorities, love our neighbours and even our enemies, guard our hearts, seek peace, etc., etc. Pastors also need to teach congregants to put politics in its proper place, recognizing a peoplehood, solidarity, kingdom, and authority that exceeds and relativizes all temporal ones.

They are not there loyally to represent a congregation’s perceived interests, but as guardians of their souls.

Pastors are ministers of Jesus Christ, charged to present his rule and truth. They must beware of aligning with partisans of left or right. They have a particular responsibility to address inconvenient realities to their audience. They are not there to underwrite the political and sociocultural prejudices and identities of their hearers and fulminate against the evils of their adversaries, bolstering their audiences in self-righteousness, but to call them to the humility of repentance and faith. They must love and humbly minister to their congregations, but they are not mere servants of and advocates for those congregations, but servants of Christ to them—Christ is their Master, not their congregants. They are not there loyally to represent a congregation’s perceived interests, but as guardians of their souls.

There is a kind of prophetic character to such ministry, chiefly challenging rather than flattering its primary hearers, neither aligning with them nor presenting God as a partisan for their causes and sides (nor as an opposing partisan), but graciously exhorting them to align with God and his word. Such ministry does not speak into a ‘metacontext’ of society at large, but to defined and bounded congregations. If a congregation is largely politically right-leaning, for instance, the ministry may need to focus more on the sins of the right. It preaches to those in its pews.

This said, the concerns of a faithful pastor really cannot be adequately understood within a left-right framing and, in tackling the sins characteristic of a particular political leaning, a faithful pastor should seldom merely be pressing the interests and concerns of the opposing side. Such a pastor is not responsible to advance the interests of the political right or left, nor to establish some supposed balance or mediating path between them, but to establish and maintain the spiritual integrity of a congregation firmly grounded in God’s truth. Faced with the crosswinds of partisan politics, the appropriate response is not reactive or corrective movements to right or left against prevailing pressures, but the deeper rootedness in God’s truth that will enable people to resist them.

For instance, pastors must protect their congregations from evils on both right and left and so ‘No Enemies on the Right/Left’ approaches must be resisted. In some respects, the most important ‘political’ message pastors might bring to many of their congregants concerns the existence of realities of ultimate concern beyond and above the frame of temporal politics with which they are so often excessively preoccupied. Such an ‘apophatic’ message concerning the realm of politics should not deny the value or importance of political activity, nor overstretch the authority proper to ministers, but keep politics in its proper place.

For those who think in terms of total and pervasive conflict between right and left, criticizing or cramping the style of either side is apt to get one accused of siding with the other. Yet to uphold the well-being of the Church and to declare God’s truth with candour will frequently make its ministers inconvenient and unwelcome to partisans who would far prefer ministers restrict themselves to exposing the many faults of their political opponents. The task of speaking with candour about spiritual dangers for the sake of the well-being of the Church, the integrity of its message, and the protection of the souls of its members is, however, one easily undermined or waylaid if pastors become overly preoccupied with speaking to matters of their society’s politics.

There are huge spiritual dangers in politics, yet it is also an important area where Christians should be active as Christians. With few exceptions, pastors are not equipped to speak authoritatively to broader political questions, and in almost all cases such speech falls outside the remit of their ministerial vocation. This does not mean their voices are not necessary. The dismissal of the voices of pastors by some has allowed for vicious and divisive political movements to develop in various Christian contexts. However, where pastors have spoken beyond their expertise, competence, and calling they have weakened or squandered an authority that is much needed.

James Eglinton recently remarked upon the dangers that scholarship faces when it adopts the partisanship of activism. He argues that we need to move beyond ‘the binary of “every single thing an academic does is politics” vs “scholarship is neutral and apolitical.”’ Something similar needs to be said about Christian ministry: it must be able to avoid both being assimilated or submerged into politics, or being utterly abstracted and detached from it. To return to a point made earlier in this discussion, Christian ministry must not allow itself to be narrowly framed by politics, its sides, and its concerns, but must be able to bring concerns to bear upon our political endeavours that will often exceed and frustrate them. Of course, Eglinton’s points about scholarship and activism very much apply to the task of theologians and Christian ethicists.

For instance, it is easy to make idols of our causes, sides, parties, and tribes. A task of faithful ministers is to ensure this does not happen, always bringing us and our causes back before the bar of God’s truth. Our highest loyalty and service belongs to him alone. A good indication that a cause has become an idol is when loyalty to, alignment with, service of, and advocacy for it becomes a principal test of faithfulness, mark of membership, and ground of unity, and when no questioning, challenging, or counteracting of it is tolerated.

There are various ways in which the authority of Christian teaching might be brought to bear upon politics. Sometimes the authority of the word of God itself is being more directly ministered, binding and loosing, or the ‘thus saith the Lord’ has clear and manifest bearing upon matters of the day. On other occasions, in the work of theologians or ethicists, for instance, the authoritative bearing of the word of God on some matter is being elucidated, even if the theologian is not speaking with ministerial authority and the bearing is less immediately apparent. Often theologians and ethicists must exercise an advisory role, bringing theological and moral concerns to bear upon political questions and deliberations, without those concerns being sufficient to settle the issues under debate. The ‘authority’ involved in such cases might also include the recognized expertise, rigour, and knowledge of scholars.

An important situation for us to consider relates to the task of Christian ministers as those who often exercise a leading role in administrating practical matters of their congregations’ lives. This became especially challenging during COVID, when government bodies made often unpopular policies, and church leaders needed to decide whether and how to implement these in their churches, especially when many of their congregants were fiercely opposed. Pastors had little choice but to take positions on these divisive matters, even when their prudential decisions on such matters—which ultimately depended on epidemiological and policy judgments well beyond their competence—were being treated as shibboleths by many people in their churches.

In these circumstances, several important Christian commitments and values started to be placed in various degrees of tension, among them the maintenance of the ordinary ministry of the word and sacraments, pastors’ proper commitment to and concern for their congregants, Christian honouring of and submission to civil authorities, the prerogative of civil and church authorities to rule on adiaphora and the duty of people to submit, the honouring of conscience and persuasion over coercion, the duty of Christians to honour their church leaders, the importance of pastors trying to remain within their area of competence, our duty to love and seek peace with our neighbours within and without the Church, the importance of seeking to preserve and practice unity in the Church, and a very high threshold of proof for placing the church in the political position of acting and advocating against the authorities and their policies (and even more so for gainsaying medical experts informing government policy). Many pastors might have considered upholding government guidelines and requirements and encouraging congregants to observe them as appropriate submission to authorities, not usurping the task of government or getting political. However to many in the pews, such behaviour was perceived as a betrayal of their interests, ‘getting political’ precisely in pushing a divisive issue.

Feelings ran high among many supporters of COVID policies—from lockdowns, to social distancing measures, to vaccination—and they made grossly immoderate claims. Rather than merely handling the issue in terms of appropriate honouring of and submission to fallible yet lawful authorities in adiaphora, with clear recognition of the importance of freedom to differ in opinion, to voice such opinions, and to seek to change policies, some (idolatrously) raised COVID policies to the level of conscience-binding shibboleths and, rather than working to preserve what unity (of spirit and of fellowship) could be preserved across differences of opinion, weaponized them in ways that could practically excommunicate others. Yes, opponents of COVID policies had far-reaching faults, but their faults were more typically expressed in divisive and uncharitable rejections of authority than in wrongful exercises of it, which is the issue under consideration here.

In navigating such issues, churches need to avoid unnecessary division. Secondary issues (such as support for or opposition to COVID measures) should not be made primary, nor treated as shibboleths or tests of fellowship. Tribal or partisan matters should not be elevated. In its practical effectiveness, much pastoral authority operates, not as a coercive or punitive authority, but through appeal and persuasion. Consequently, pastors will rightly seek to minimize unnecessary division and polarization, and to maintain trust and good will with their congregants. For their part, lay people have a responsibility of being tractable to and honouring their leaders—healthy authority is collaborative in ways that people seldom consider.

Pastors and Christian teachers need to be clear—in their own minds, and with their hearers—about the forms of authority they are exercising. In speaking to their congregations from the pulpit, they may often be speaking with the force of a conscience-binding ‘thus saith the Lord’, declaring God’s authoritative word as its ministers. In other cases, they may speak with the ‘authority’ of the scholar, who has expertise they have devoted to the exploration of a matter. On some occasions they may be bringing general moral principles to bear upon specific prudential circumstances, hopefully mediating through wise yet non-binding counsel insight into what a person ought to do. In yet others, they are figures with some prerogative to determine church policies, to which others must submit. In less common situations, they might be advocates for recognition of and submission to other fallible yet lawful authorities. Differentiating between these is essential.

Pastors can inappropriately bind consciences on issues beyond their competence, such as how people ought to vote. While it is not inappropriate for them to give counsel or to express opinions on such prudential matters, making stronger claims than this for their speech in such matters is likely an abuse of their proper authority. Nevertheless, without binding consciences, pastors do need to excite and inform people’s consciences on prudential questions, including that of how they ought to vote. Such questions may be matters of wisdom, but this does not mean that there are not ethical duties pertaining to them nor scriptural teaching that has bearing upon them.

In some situations, overreaching of pastoral authority may be appreciated, sometimes because it underwrites people’s existing beliefs, but sometimes because people have a desire for the (false) certainty and the social consensus such claims can offer. Yet it is also the case that, where people perceive their pastors to be speaking regularly with an unwarranted authority to matters beyond their competence, they may soon find that even the authority that is proper to them is dismissed. Showing due honour to the authority, government, and expertise of others can strengthen people’s regard for one’s own. This also applies to our relation with rulers in our wider contexts.

Even where appropriate distinctions are drawn, pastors (and others) need to be good stewards of the authority entrusted to them. They should beware of squandering authority for matters of lesser importance; they should pick their battles. They should seek to establish and maintain a good reputation with people, so that, when they need to speak with some authority to them, their words may be more heeded, and heard in the right way. They should be very alert to the danger of excessive participation in discourse in places like the Internet, where the field is flattened out and authority is ineffective and corroded. Likewise, persisting in speaking to non-receptive hearers can devalue one’s words.

Churches, ministers, and other Christian teachers engaging in political speech have great reason for care and caution. There is a political character to the essential Christian message, yet this political character is often more apophatically related to the political structures of the present age. Christian ethics and teaching can have weighty bearing upon many political questions, and upon our relationship to politics more broadly, even when they may not be dispositive. And, even in cases where they might be, the deliberative processes by which what is entailed by such bearing could be determined with clarity are complex and those engaging in the deliberation quite fallible.

Characteristics of Dysfunctional Communities

I have commented on some contemporary uses of the work of Edwin Friedman on this Substack before. In my previous discussion, I noted the way that Friedman’s analysis had been heavily gendered by some subsequent interpreters, in ways that it was not in Friedman’s own work. Admittedly, this later gendering should not be entirely surprising given the prominence of the term of ‘empathy’ in parts of Friedman’s account.

While the term ‘empathy’ might have the effect of foregrounding more commonly feminine relational impulses, Friedman’s analysis of dysfunctional communities clearly also applies to dynamics more typical of male-dominated groups. Consequently, if we allow the gendered weighting of the term ‘empathy’ to direct our attention too much, we can miss much of the application of his work. Indeed, in some respects we may even become more susceptible to some of the problems he identifies.

Friedman explores the way in which dysfunctional communities can come to order themselves around their most disruptive, demanding, immature, and un-self-regulated members, as leaders lack the nerve, will, character, support, or capacity effectively to stand up to them. In such situations the expectation can be that the family, group, or society bend over backwards to appease, accommodate, avoid offending, or coddle the dysfunctional member or members. It is easier to expect everyone to change around the disruptive persons than to confront them and provoke their displeasure.

In many places and institutions within our society, as well as in many churches and Christian organizations, this dysfunctional herding dynamic is typically encountered in more feminine modes. However, it can be no less operative in more masculine-coded forms and contexts. While feminine groups may be more susceptible to such herding dynamics that depend upon appeals to empathy, there are several other ways that they can operate.

It can, for instance, take the form of appeasement strategies designed to avoid confrontation, insistence upon unity in response to bad behaviour being challenged, pressure upon and blaming of those who expose or challenge it, and lots of effort being expended to justify, minimize, or excuse it. Rather than appealing to empathy, the disruptive person might get their way through intimidation and violence, through creating a scene or throwing a tantrum, by making life deeply unpleasant and tense for everyone around them when opposed, through constant taking of umbrage and offence, through spreading complaints and bitterness, through spreading distrust and accusations about leaders, or through exciting division and conflict in the ranks in other ways. Faced with such people in a society, organization, church, or family, the easiest course will often seem to be that of giving them their way, making excuses for them, and resisting anyone who would unsettle the situation by standing up to the disruptors. Anyone who challenges the most immature and dysfunctional group members can be characterized as divisive; it is easier to silence such voices than to put the dysfunctional and immature parties in their place, which could easily result in elevated internal conflict.

The tensions created by such a situation will typically be displaced onto others. There will be those who constantly must try to defuse tensions through humour. Others will make sophisticated excuses and rationalizations for the disruptors. Others may attack any who challenge the disruptors and shift the blame for any unpleasantness caused by the disruptors onto them. Many will be walking on eggshells around the disruptive figures or flattering them in various ways. So much of this results from conflict-avoidant desire for in-group unity (often accompanied by raised external conflict to channel internal tensions), association of apology with weakness, and urge to appease and cover for dysfunctional and restive group members and elements.

Groups that adopt such an approach often have genuinely mature and gifted people within them, yet their incapacity to exercise decisive self-regulation and policing means that they will consistently be waylaid by their loud and immature elements. One of the effects and symptoms of such a regressive dynamic is that entire families, institutions, movements, groups, churches, denominations, societies, etc. become ordered around and known for their most immature and dysfunctional members, behaviours, and actions. As such groups continue to accommodate and adapt themselves to the disruptors in various ways, their entire character will gradually become coloured by those of their immature and disruptive members.

In such settings, people who could be smart, respected, and good leaders within well-regulated organizations and societies can end up devoting their reputational capital, time, and energies to providing intellectual cover and excuses for fools and for foolish actions and statements that people lack the maturity to retract.

Recognizing this, it might be diagnostically helpful to ask which figures are most dominant in our own group’s public profiles, what sides of them are most prominently displayed, and what and who our public discourse most amplifies. If the most dominant figures are fools, provocateurs, and even vicious people and our groups are constantly rallying to provide intellectual cover and excuses for dumb incendiary statements, imprudent or sinful actions, and immature or bad persons, it is a strong indication that we have a serious problem.

Internal criticism, retraction of bad statements, apology for wrong or imprudent actions, discipline for unruly parties, etc. are all ways that we can protect ourselves from becoming tethered to folly and evil, enabling us and our communities to put our best feet forward.

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ The latest episodes of Mere Fidelity are on The Tribe of Levi and Women’s Ordination, Put Social Media in Its Place, for which we were joined by Andy Crouch, Spiritual-Not-Religious: Orphic Mysteries and Modern Attitudes, with Dr. Michael Horton, and Fishy Numbers in the Bible, in which we discuss odd and symbolic numbers in Scripture and the challenge of historicity.

❧ The Theopolis Podcast’s Deuteronomy series continues, with episodes on Deuteronomy 29: Secret Things Belong to the Lord, Deuteronomy 30: The Choice of Life and Death, and Deuteronomy 31: Joshua Commissioned to Lead Israel.

❧ My twenty-hour-long Theopolis Exodus course is available to those who have signed up for the Theopolis App.

❧ The first of a series of videos on the subject of Pentecostal politics has just been published.

❧ I recorded a version of a recent Substack post on the deception of Isaac.

Upcoming Events

❧ Much of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Alastair and Susannah

We had a lovely dinner in the Cotswolds this past summer. We finished it with our first taste of sticky toffee pudding. That is pretty decent stuff!