№ 31: Breakfast and Move Things

And some Purim thoughts on why Mordecai did not bow to Haman

Dear friends,

Susannah: We’ve spent the last three weeks or so, since our return from Venice, in a massive house move, which went far more smoothly than we had anticipated. Alastair’s father has Parkinson’s, which has meant that he and Alastair’s mum have moved into an assisted living flat just a few miles from their big old three story house; we have been incredibly blessed by their generosity in giving us that house. So we’ve moved from our tiny busting-at-the-seams house to this lovely home; the next step is to put our former house on the market.

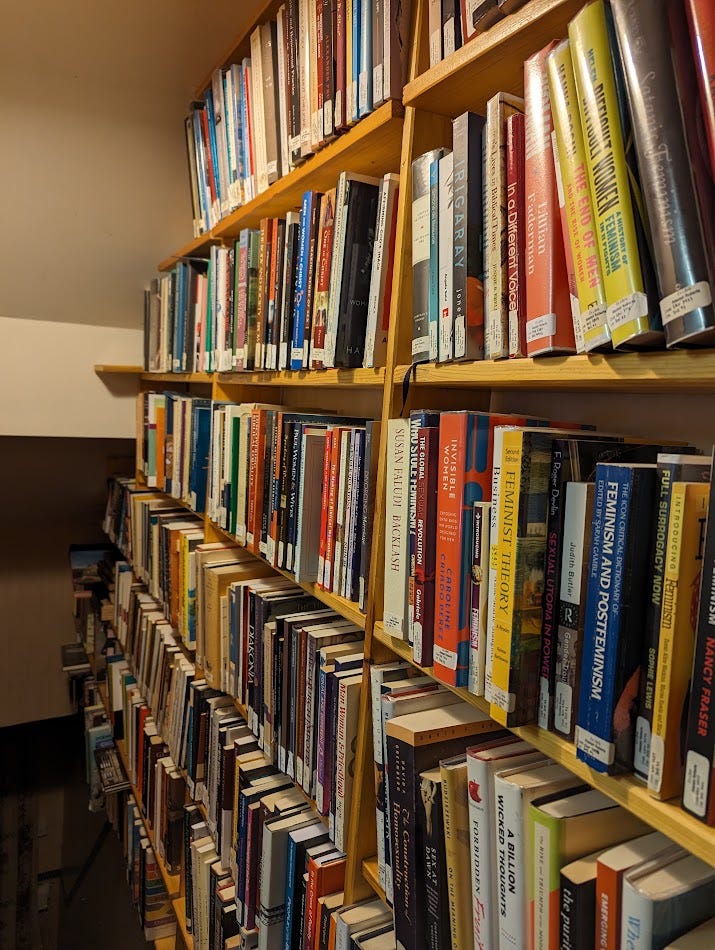

I’ve had an enormous amount of fun sorting out housewares and decor—lots more to do, but the new place very much begins to feel like ours, and Alastair’s parents have let us keep many of the special pieces of furniture and decoration; it feels very graciously like a blend of two generations. And I’m absolutely in love with my office, a big sunny corner room at the front of the house which I’ve lined with bookshelves. For possibly the first time in my life… I have enough bookshelves. There are EMPTY BOOKSHELVES IN MY OFFICE. Wild stuff, man. As Alastair’s mum points out, it is unlikely that the situation will last, however.

We’ve been slightly obsessively going to the antique store right down the road from us to stalk various pieces of furniture; it’s probably the best antique store I’ve ever been in, absolutely jammed with beautiful, well-preserved 19th and early 20th c furniture, as well as miscellaneous taxidermied stoats and signal lamps and suits of armor and so on. (The suit of armor is nearly £700, otherwise we would be very very tempted.)

Alastair wanted to get me a housewarming gift, so I chose a gorgeous Edwardian mahogany desk. (And then we went into another local antique store/junk shop and found a perfectly preserved 100-year-old Singer sewing machine in working order for £30 so he got that for me too—every Carnevale I get inspired to learn to sew; I now have a sewing machine on both sides of the Atlantic and no excuse.)

It’s all just lovely. I’m very happy here.

But… I am extremely excited to be heading back to NYC, in less than a week.

Alastair: I ended my update in our previous Substack post with a request for prayer, as we faced an intense next few weeks of moving. It is now three weeks later, and not more than ten minutes ago we moved the last residual boxes of our items out of our old house and into the new.

Our house is not entirely ‘new’: I lived here from the age of sixteen and my parents have been here for a quarter of a century. In both New York and in Stoke-on-Trent, we now live in childhood and family homes. While we travel frequently and extensively, we have deep roots in our places.

The prospect of the move was extremely daunting. My parents needed to be moved out of the house and into their apartment, while we had to move out of our old house and move in, so there were essentially two moves to accomplish.

It is difficult to imagine how the move could have been achieved had it not been for my brother Jonathan, who came over from Germany for a week to assist with the process. Jonathan stayed with us and headed over to the house every morning to help my parents, with a full carload of our boxes. Jonathan’s work and the help given by my other two brothers, Peter and Mark (who had come over from France to spend a few days with my parents before the move), was a powerful reminder of the blessing of a close-knit family.

Jonathan usually visits with his family, but this time was by himself, which gave us more uninterrupted time with him. In his free time, Susannah and I were also able to watch Dune: Part Two with him, which we thoroughly enjoyed.

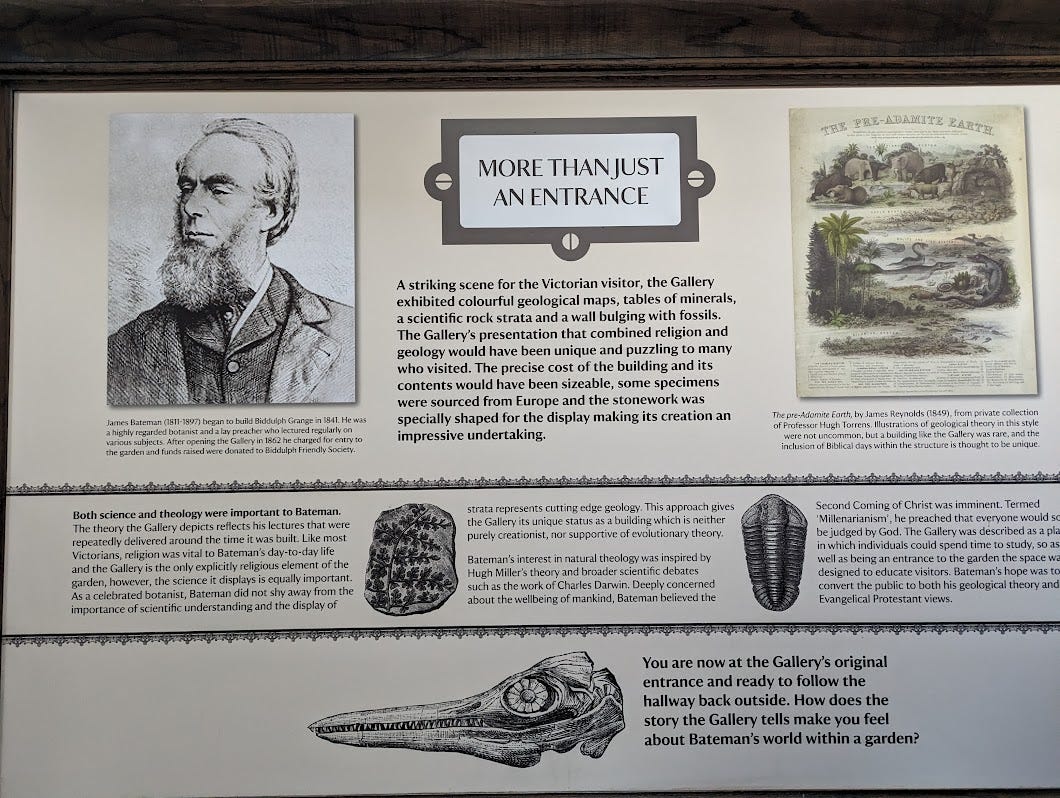

Although it is on our doorstep, I have never previously visited Biddulph Grange Garden. It turns out that it is a beautiful National Trust property. We passed a pleasant early afternoon looking around with Jonathan. For all the negative press Stoke-on-Trent gets, I never cease to be amazed at the wonderful places that are to be found in our area!

The man who built Biddulph Grange Hall was fascinated with geology and with theology. The entrance is devoted to a display of geological finds mapped onto the days of creation from Genesis 1.

Not content with all the moving he accomplished, Jonathan also cooked us some delicious breakfasts over the course of his stay.

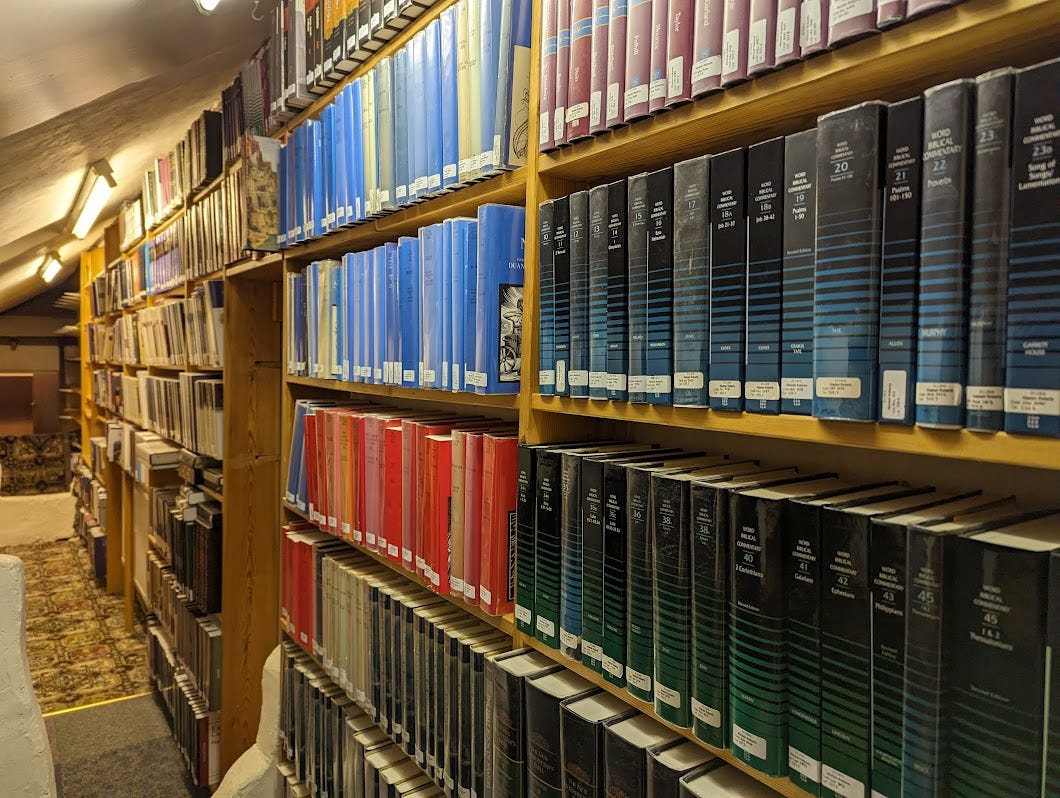

We probably have over six thousand of our books on this side of the Atlantic, so moving them all was no small task. While Susannah’s library is chaotic, mine is Dewey-coded, part of them ordered on shelves, with the rest stored in numbered boxes, the contents of all catalogued in a spreadsheet. Putting everything back in its appropriate place was quite an operation!

Over the course of a week, I moved about a couple of hundred boxes of books, including singlehandedly carrying over fifty full A3-sized boxes to the loft of our new house, where I now have my office and library. It was an exhausting and time-consuming task, as was unpacking all the books and putting them in their correct order. Thankfully, I now have considerably more shelf space, which opens wonderful new possibilities! There are over one hundred boxes in our basement and garage, some of which I might be able to remove and place on actual shelves.

As we had been so busy with our own move, we had not had opportunity properly to see my parents’ new apartment. We finally visited them last Wednesday. After all the anxiety and concern leading up to the move, it was nothing short of remarkable how smoothly the move went for my parents and how happily they have settled into their new apartment. Thank you so much to any of you who prayed for us! My parents are already fitting into life in the sheltered accommodation, making friends with neighbours and other residents, and their apartment feels wonderfully homely.

Even besides all the moving, it has been a busy few weeks. I finished teaching my Bible and Politics course. I have written many thousands of words, recorded several podcasts, taught a few classes, supervised a number of students, and had many lengthy work calls.

Tomorrow morning, I preach for Palm Sunday. After an abortive attempt at a cycle ride yesterday afternoon—we ended up having to sort out a slow puncture on my bike—we are also hoping to have a pleasant cycle ride in the afternoon.

Over the last month I have also finished one knitting project and started another. My current project is a cardigan that I will need to ‘steek’, my first time using such a method, which is utterly terrifying! After making some reinforcing stitches, I will have to cut the work from top to bottom, hoping that it does not all unravel. We will see how that goes…

Monday is going to be a day of frantic work and preparation. We travel down to London on Tuesday and back over to the US on Wednesday. We are excited to be back with various of our US friends for Easter!

Why Mordecai Did Not Bow

This Lenten season my thoughts have especially been occupied with the ‘political’ character of the events of Holy Week, a ‘political’ character that eclipses and subverts the lesser forms of politics that typically demand our attention. My Davenant Hall course on The Bible and Politics has just concluded, during which I revisited Oliver O’Donovan’s brilliant The Desire of the Nations, as I had set it as the primary text for the course. I will be preaching on the Triumphal Entry this Sunday, which will give me further opportunity to reflect upon such matters. My meditation on the cross in our last Substack post is a further example of issues that have been upon my mind.

However, while we are nearing Holy Week, this evening is also the start of the feast of Purim and, as the book of Esther has been a subject of discussion for me over the past fortnight, it did not seem unfitting to post some thoughts on the subject. My friend and Theopolis Institute colleague James Bejon has written on the connections between Esther and themes of resurrection, but the question I wanted to take up here is the puzzling one of why Mordecai did not bow to Haman.

The account of Mordecai the Jew’s refusal to bow to Haman is found in Esther 3:1-6—

After these things King Ahasuerus promoted Haman the Agagite, the son of Hammedatha, and advanced him and set his throne above all the officials who were with him. And all the king’s servants who were at the king’s gate bowed down and paid homage to Haman, for the king had so commanded concerning him. But Mordecai did not bow down or pay homage. Then the king’s servants who were at the king’s gate said to Mordecai, “Why do you transgress the king’s command?” And when they spoke to him day after day and he would not listen to them, they told Haman, in order to see whether Mordecai’s words would stand, for he had told them that he was a Jew. And when Haman saw that Mordecai did not bow down or pay homage to him, Haman was filled with fury. But he disdained to lay hands on Mordecai alone. So, as they had made known to him the people of Mordecai, Haman sought to destroy all the Jews, the people of Mordecai, throughout the whole kingdom of Ahasuerus.

No clear explanation for Mordecai’s refusal to bow to Haman is given within the text, so readers and commentators have been left to speculate concerning his reasons, reading between various lines. The moral character of Mordecai’s refusal to bow has also been much debated. Several commentators, including two of my greatest theological influences, James Jordan and Peter Leithart, have argued that, in his refusal to bow, Mordecai was being rebellious, sinning against God and the king.

Differing explanations have been advanced for Mordecai’s refusal to bow. In his series of Biblical Horizons newsletters on the book, Jordan presents Mordecai as wilfully rebellious [BH#226], suggesting that he exhibited the more general tendency of the Jews of his day to do their own thing and not respect the king’s commands (cf. Esther 3:8). That Haman was exalted immediately after Mordecai foiled Bigthan and Teresh’s plot, while Mordecai himself went unrewarded, is a detail that Jordan and Leithart both note, suggesting that personal resentment might also have been a factor in Mordecai’s attitude to Haman.

Explanations for Mordecai’s refusal to bow frequently involve some grounding in Mordecai’s Jewish identity, on account of the ending of verse 4 of the chapter. For Jordan it is a more general insubordination on the part of Mordecai and the Jews of his day. Others note that Haman is introduced to us as an Agagite, seemingly a descendant of the Amalekite king of 1 Samuel 15. Does the ancestral and divinely appointed enmity between the Israelites and the Amalekites (cf. Deuteronomy 25:17-19) justify Mordecai’s refusal to accord Haman any honour? One historic line of Jewish interpretation sees the rationale for Mordecai’s refusal to bow in the Jewish opposition to idolatry. To drive this point home, the story was retold with Haman bearing an idolatrous image upon his breast.

Perhaps my favourite commentator on the book of Esther is Rabbi David Fohrman, the author of The Queen You Thought You Knew; Fohrman has also produced several videos on the book of Esther on his AlephBeta.org website. He makes the case that Mordecai was justified in his refusal to bow, recognizing Haman as an unfaithful servant to the king. As Mordecai honoured King Ahasuerus, he could not bow to such a man.

Fohrman notes an allusion to Genesis 39:10 in Esther 3:4.

And as she spoke to Joseph day after day, he would not listen to her, to lie beside her or to be with her.—Genesis 39:10

And when they spoke to him day after day and he would not listen to them…—Esther 3:4a

This allusion suggests some analogy or connection between the situation in which Joseph and Mordecai found themselves. This, of course, is one of several such analogies between Mordecai and Joseph—analogies that are widely recognized by commentators—strengthening the claim that it is not accidental. Like Joseph, Mordecai is a man taken from his homeland and exiled in a foreign land. While there he rises to the highest status in the court. Further parallels with Joseph can be found in the story of Daniel. Fohrman claims that, as the rest of the story evidences, Haman was a man of excessive ambition, ambition that led him to desire to play the part of the king, rather than being a faithful servant under him. He suggests that we are justified in suspecting that the king’s supposed command that people bow to Haman was not what Haman wanted it to appear to be, but was likely misreported or twisted by Haman for his self-aggrandizement.

While it is possible that the allusion to the story of Joseph might be inviting a comparison rather than a contrast between the two characters, one reflecting unfavourably upon Mordecai, this seems unlikely. Such a contrast would seem to be situated in a strange place. It would not be a contrast between one man who faithfully resisted persistent temptation and one who did not, but the much less effective contrast between one man who faithfully resisted persistent temptation and one who was persistently resistant to a lawful authority.

Fohrman fleshes out the comparison between Joseph and Mordecai suggested by the allusion. Like Joseph, Mordecai is under the rule of a foreign master to whom he is faithful—Potiphar in the former case, King Ahasuerus in the latter. The second-in-command, however—Potiphar’s wife in the former case, Haman in the latter—is unfaithful and seeks to make the faithful Hebrew servant complicit in their unfaithfulness. Potiphar’s wife wants Joseph to lie with her and Haman wants Mordecai to bow to him. In both cases, a servant who is in fact faithful appears unfaithful when he is accused.

While Haman’s expectation that others bow to him is one expression of his overweening ambition, this should not be confused for the stronger claim that some have made that Mordecai refused to bow because any such bowing to a human is idolatrous. As we see in places like Genesis 23:7, there is nothing wrong with bowing to human beings in principle. Indeed, later in the book of Esther, Mordecai himself would receive high honours and expressions of homage.

The end of Esther 3:4—‘for he had told them that he was a Jew’—has been read by many as Mordecai’s rationale for his refusal to bow. Yet Fohrman’s reading suggests the possibility that the others of the king’s servants were not in any doubt regarding Mordecai’s reasons for not bowing to Haman. As Potiphar’s wife with Joseph, they were seeking to break down Mordecai’s resistance, rather than to discover the reasons for it. Mordecai’s telling them that he was a Jew was not Mordecai’s reason for not bowing, but the king’s servants’ reason for informing Haman concerning him. As Potiphar’s wife highlighted Joseph’s outsider identity as a Hebrew (Genesis 39:14, 17) to get the other servants (who presumably knew of her unfaithfulness to Potiphar) on her side, so Mordecai’s Jewish identity motivates the rivalrous king’s servants to inform on him.

Within the framework provided by such a reading, Fohrman suggests that we can make sense of elements of the readings found in the Jewish tradition that speak of bowing to Haman as idolatry and which depict him as having an idol on his chest. Such a depiction need not be taken as a literal claim about the objective historical reality, but as a creative representation indicating a deeper reality in the story. The point of the depiction is not that Haman actually had an idol on his body, but that Haman had assumed the character of an idol. Yoram Hazony notes comparable claims concerning an idol hanging over the bed of Potiphar’s wife (God and Politics in Esther, 57). While it is legitimate to bow to other human beings under some circumstances, in Haman’s case such bowing would have been idolatrous—or at least analogous to idolatry, as a granting of honour to a lesser authority in a manner constituting rebellion against a higher. The idol lays claim to things that are God’s sole prerogative.

In God and Politics in Esther, Yoram Hazony suggests that we read the figure of Haman more carefully against the backdrop of the preceding chapters. In chapter 1, King Ahasuerus was surrounded by wise counsellors (1:14-15). Yet, after the rebellion of two of the chief servants of the king, Bigthan and Teresh, Ahasuerus embarked upon a radical reordering of his court. Queen Vashti’s removal from office after her rebellion occasioned the elevation of Esther, a woman who was not of one of the noble families of the kingdom (perhaps a reaction to the situation with Queen Vashti, designed to curb the power of such families), and Ahasuerus’s reordering of his court after the failed coup of Bigthan and Teresh was even more far-reaching. In place of his many advisors, Ahasuerus appointed just one man over them all, Haman the Agagite.

One could perhaps compare the situation to President Paul von Hindenburg making Adolf Hitler chancellor of Germany and the subsequent passing of the Enabling Act, paving the way for the rise of a dictator, Hindenburg’s reduction to something arguably nearer to a puppet, and the radical transformation of the Germany polity into a totalitarian system, under the cult-like dominance of Hitler and his party. Within the new Persian regime, while Ahasuerus remained the figurehead, actual power was increasingly wielded by an unrivalled and unchecked Haman, the Grima Wormtongue to Ahasuerus’s King Théoden. With the rise of Haman, Hazony argues, Persia was lurching in the direction of a form of totalitarianism. As many have recognized, in such situations of concentrated and monopolistic power, the state and its most powerful leader can quickly assume an idolatrous status. Continuing the analogy, one might compare Mordecai’s refusal to bow to Haman to August Landmesser’s alleged refusal to perform the Nazi salute at a rally. Haman’s attempt to enact state-sponsored genocide and his extrajudicial attempts to kill opponents might invite further comparisons. Within this reading, Mordecai appears as a brave isolated figure of dissent in an illegitimate regime, resisting the immense wave of social pressure supporting it and courageously putting his own life in jeopardy.

Such a reading, it should be noted, is certainly reading between several lines, especially in its more developed form, within which there is a lot of speculation. As the explicit details of the text leave many questions unanswered, such reading between the lines is something which every proposed understanding of Mordecai’s actions engages in. What matters is whether our readings, arrived at through close inductive consideration of the text, and our more elaborate speculations, make good sense of the text. To make good sense of the text, they must give a strong account of both what the text says and what it does not say. Our reading of the text will have the character of a hypothesis and will be tested by how effectively they explain the text in front of us. Readings whose weight of meaning rests overmuch upon details that are absent from the text are poor, for instance. If we were to argue that Mordecai did not bow to Haman because Haman was literally wearing an idol on his chest, the centre of gravity of such a reading would no longer be firmly situated above the actual text—the book of Esther itself makes no reference to such an idol—and it would be profoundly unstable. If we are trying to make sense of the text by positing an explanatory detail about which the text is entirely silent and to which it makes no allusion, the text itself would seem to be lacking.

While we should be wary of claiming that our particular reading of a text such as Esther, whose interpretation requires so much uncertain induction, hypothesizing, and speculation, is the one way that it must be read, it is evident that some readings are better than others and that different readings have both their points of strength and weakness. We need to be aware of those places where our readings become more speculative and also be alert to the elements of our readings that are load-bearing, and those elements that are speculations upon which little of weight rests and which might readily be abandoned with little loss.

Here are a few of the considerations that weigh upon my own reading of this text, inclining me towards a position close to that of Rabbi David Fohrman and away from the claims of James Jordan concerning Mordecai’s rebellion (I should note that, as one would expect, Jordan’s commentary on the book is packed with insight and that, even though his reading of Mordecai and his actions has significant impact upon his broader interpretation, even those differing from him on this point will find much of great value in his treatment).

Many of the considerations I will mention have to do with effective storytelling. The book of Esther is not merely a bare and artless record of historical events: it is a story and it needs to work on that level. As a story it has persons who are characterized in various ways and who play roles within the narrative (e.g. hero or villain). It has a plot and it has a resolution. It employs literary devices. It sets up figures as foils for each other, it juxtaposes scenes, it alludes to other texts, etc. However we propose to read the book of Esther, it needs to be effective and satisfying as a story. A story that requires extensive accompanying explanatory material to direct you away from misreadings to which the text is extremely vulnerable is probably not very effective.

First, Mordecai’s prominence in the book and the analogies between him and other biblical heroes like Joseph weigh against such a negative reading of his actions in such critical and precipitating events in the narrative. As David Daube has observed, were one merely to read the contents of the book of Esther, one might plausibly think that ‘Mordecai’ would be a more natural title than ‘Esther’. Esther 2:5 introduces Mordecai before Esther and the book’s final chapter focuses almost entirely upon Mordecai and his relationship with the king, saying nothing about Esther (while chapter divisions are not inspired, the structure of the book gives Mordecai great prominence). Mordecai’s actions precipitate the central drama of the book and, as Fohrman argues, it is Mordecai’s wise plan that secures its ultimate resolution: though essential, Esther’s bravery was not sufficient to overturn Haman’s edict. If Mordecai were indeed a rebellious, resentful, and insubordinate man, his broader place in the book might be difficult to account for. A reading of Mordecai’s actions as heroic would move more naturally with the seeming grain of the text, within which he seems to play a narrative role of heroic protagonist.

Second, where Mordecai’s less disputed actions are seen, they would seem to characterize him as a hero. He is a committed guardian of Esther, whom he adopted as an orphan. It is Mordecai who exhorts Esther to her brave actions. Mordecai seems to be a faithful and courageous servant of the king when he exposes the treachery of Bigthan and Teresh. He is the shrewd counsellor and prudent vizier, who brilliantly frustrates Haman’s plot with his counter-edict and wisely manages the kingdom. Such details suggest that he is wise, righteous, courageous, principled, and loyal. While people can definitely act imprudently or do things that are out of character, where clear indications to the contrary are lacking, we will naturally presume that they are acting according to what we already know about their characters.

Third, immediately before Mordecai’s refusal to bow, he is presented as a more than faithful servant of King Ahasuerus. He reveals a plot to kill the king, presumably at some risk to himself. Revealing the treachery of high officials (Bigthan and Teresh might be among the officials mentioned in 1:10 and 13, perhaps Bigtha and Tarshish) was likely a dangerous venture, making him a potential target for some powerful people, and requiring considerable courage on Mordecai’s part. That someone prepared to engage in such brave action in service to Ahasuerus would be engaged in wilful and reckless rebellion against the king’s commandment only a few verses later is strange indeed!

Given the extreme stakes of the situation—Mordecai almost paid for his defiance with his life and his people were almost destroyed on account of it—we must suppose that he was exceedingly stupid, wilfully reckless, or courageous and principled. Most commentators opt for the final option, although some consider Mordecai to have been motivated by misguided scruples. There is nothing to suggest that Mordecai’s refusal to bow was a more general posture of insubordination—he had just exposed the plot against the king—nor that it arose out of more general scruples about idolatry. Had it arisen from sincere yet misguided scruples, one imagines it would be handled rather differently. If such scruples were at play, Mordecai might also have resisted the honours he was granted in chapters 6 and 8.

Fourth, if we decide to regard Mordecai’s refusal to bow to Haman as a reckless and wilful act of rebellion that almost cost the lives of his entire people, this interpretative move will need to be followed through consistently. The Mordecai that we see later in the book, in chapters 8-10, is a man of immense wisdom and prudence, entrusted with much of the management of an empire, hardly what one would expect of a resentful, insubordinate, and reckless man, a man of ‘stupidity and hubris’ in Jordan’s characterization [BH#229]. In Jordan’s reading, there is no clear repentance from Mordecai. While some have suggested that his fasting and mourning and his charge to Esther constitutes his repentance, Jordan claims that Mordecai’s supposed reckless and wilful insubordination to Haman continues beyond this point (cf. 5:9). Even Mordecai’s charge to Esther in chapter 4 is regarded as Mordecai thinking merely politically.

By the logic of Jordan’s reading, Mordecai would also seem to be utterly unfit for the high office he comes to enjoy. We might regard Mordecai as a recipient of mercy and grace on account of Esther’s faithfulness and courage, by which he is spared the natural consequences of his rebellion and granted a positive outcome. However, without a radical transformation of his allegedly stupid and hubristic character, he would be very unsuited for the government of the kingdom.

Fifth, the way that the character of Haman serves as a foil for the character of Mordecai presents serious problems for attempts to characterize Mordecai as a stupid and hubristic man. Haman is a comically evil man, elevated at the time when Mordecai should have been, who gets an extreme comeuppance, being hung on the gallows he had prepared for Mordecai (7:10). Mordecai gets placed over Haman’s house (8:2). Mordecai is raised to the rank of vizier (10:3), from which Haman was removed. In chapter 6, by the king’s express command, Haman is made to honour Mordecai, who had refused to honour him according to the king’s supposed command in chapter 3. Mordecai, on account of his refusal to bow, gains Haman as an opponent and their respective fortunes are intertwined and contrasted throughout.

There are several considerations of good storytelling here. Esther is manifestly a story of radically reversed fortunes, with Mordecai elevated at the end and Haman destroyed. This ending must serve as a fitting resolution of whatever the plot and themes of the book are. Yet, if the drama is chiefly precipitated by Mordecai’s wronging of Haman, as Jordan suggests, such a resolution is far from satisfying. That Mordecai’s sin and reckless folly would lead to such extreme blessing seems inappropriate. Haman has the worst of ends and Mordecai the best. Not only does Mordecai not really receive a slap on the wrist as a character, he ends up receiving the status of the guy he supposedly wronged and rebelled against! This seems like dramatic vindication and reversal. If Mordecai had sinned, this would undermine the moral force of the text relative to it.

If the story presented Mordecai as undergoing marked repentance, change of behaviour, and transformation of character, such a narrative form might perhaps work. Yet, for it to work as a story, such repentance and transformation would need to be explicit and elaborated. Further, as our hearing of a story and our understanding of events and characters within it will be shaped by our knowledge of how things turn out, Mordecai’s refusal to grant honour to a man who ends up planning a genocide and being removed from his office by the king will seem justified in the hearer’s hindsight, irrespective of whether it was justified at the time. Divergent outcomes are a typical way in which biblical narratives cast judgment upon events. That Mordecai’s refusal to bow precipitates events that lead to Haman’s downfall and Mordecai’s elevation to high status in the kingdom suggests that Mordecai’s refusal, however we understand it, ought to be regarded in a positive light. Reading Mordecai as offender and Haman as victim in this episode makes it difficult for Esther to work effectively as a story.

When large plot twists enable protagonists to avoid the moral weight of their actions and choices, we can feel that a narrative is cheating us. For instance, when a married protagonist gradually develops romantic feelings for another character, the protagonist’s wife can come to occupy the position of an obstacle. A narrative that avoided reckoning with the moral weight of such a protagonist’s adulterous desires and actions, removing the ‘obstacle’ of their wife through some plot contrivance, would grant the protagonist and the audience the fulfilment of their desire for an adulterous relationship, while dulling their sense of the sinful character of that desire. If a sinful Mordecai refused to honour Haman and then went to receive Haman’s office while Haman was removed and executed on account of his villainy, Haman’s evil response to Mordecai’s provocation would have granted Mordecai the full realization of his hubris and his insubordination to Haman, without the moral weight of Mordecai’s rebellion truly having been registered. Such a story, at least without extensive attention to Mordecai’s repentance, the renovation of his character, and the consequences of his persistent sin, would seem to have at least an amoral character.

Sixth, the narrative alludes to the story of Joseph in the house of Potiphar at a key point. Mordecai’s refusal to bow to Haman is recounted in language clearly recalling Joseph’s refusal to sleep with Potiphar’s wife. A satisfying reading of the narrative must account for such significant details, explaining how they serve the story. A straightforward reading of such an allusion, especially when coupled with the broader analogies between them, would suggest that Mordecai’s refusal to bow is an act of courageous faithfulness like Joseph’s. Joseph’s situation in Genesis 39 is somehow illuminating of Mordecai’s situation in Esther 3. Fohrman’s reading is at its strongest here, taking a widely neglected yet significant detail in the text and working with its grain to develop an expansive account of the connection between the two narratives. Jordan, notably, does not to my knowledge provide any account of this detail.

Putting the pieces together, the following is a rough speculative account of the story of Esther. While it ventures into more conjectural reading at several points, the chief claims are grounded in the details of the text and the form of the narrative.

Mordecai the Jew is daily walking around the court, which enables him to communicate with Esther. He likely holds some sort of office, seemingly being counted among the king’s servants. As he does so, he comes to see and overhear a lot of what is going on in the shadows of King Ahasuerus’s court, including the rebellion planned by Bigthan and Teresh. Ahasuerus’s court is a place of intrigue and suspicion. There are several traitors and unfaithful servants within it, along with a lot of rivalry and ambition.

Being a brave and faithful man, Mordecai exposes the plot. However, Mordecai’s revelation of the plot likely did not win him friends. Some of the courtiers with whom Mordecai brushed shoulders every day were probably sympathetic to Bigthan and Teresh. Others might have resented Mordecai, thinking that his actions would increase the king’s suspicion of his other courtiers, hurting them, while potentially advancing Mordecai in the king’s good graces. One can imagine the courtiers being wary of Mordecai, worrying whom he might inform upon next.

Following Vashti’s refusal to come at the king’s summons and the foiled coup of Bigthan and Teresh, King Ahasuerus grew increasingly paranoid. He chose a new consort from outside of the noble families and appointed Haman as his new vizier. Haman was exalted far above the several princes, wise men, officials, and counsellors mentioned in chapter 1. Haman was supposedly given command by the king that all the other officials and servants of the king should bow down to him (3:2). It is not clear that the servants were directly told this. Haman possibly just came out from the king’s presence one day, telling them all that they all needed to bow down to him. As we know from chapter 3, Haman was quite willing to deceive and mislead the king to advance his private ends.

Haman’s exaltation dramatically reordered the court. Where there had once been an assembly of princes, officials, and counsellors, power was now concentrated in the hand of Ahasuerus’s prideful new prime minister, moving the nation in a more totalitarian direction, and altering its former constitution. All other officials were expected to pay homage to Haman. The king’s servants all bowed down, but one person did not—Mordecai. Day after day the servants asked Mordecai why he would not bow. Their challenging of Mordecai was not designed to ascertain the reason for his refusal—they almost certainly already knew the reason—but to persuade Mordecai to go along with them.

Mordecai’s resistance likely angered them. It would have shown them up as unfaithful servants to King Ahasuerus and the kingdom. Had Mordecai not been bowing because Haman was an Amalekite or because bowing would be idolatry, or something like that, he would naturally have communicated the reason to the other servants of the king. He did not listen to or speak to the other servants because they were not confused about his motives and were simply trying to break down his resistance.

Haman had not noticed that Mordecai was not bowing to him until the courtiers drew his attention to the fact. They wanted to see what would happen to Mordecai’s conscientious resistance if Haman knew. That Mordecai was a Jew was a key motivation for them: he was an ethnic outsider and untrusted and disliked for this reason (3:4).

Haman was furious once they brought this to his attention. However, he could not easily tell King Ahasuerus that Mordecai was refusing to bow to him and seek to destroy him as a result. This might have exposed Haman and his own ambitions a little too much. Haman loved the trappings of royalty and high office. When he thought he had the opportunity in chapter 6, he wanted to play dress-up as the king and receive the homage due to the king. On that occasion he could sufficiently veil his own ambitions by speaking about the one whom the king delighted to honour (secretly presuming it to be him). Here, though, admitting that he was daily getting the king’s servants to render extreme homage to him and was seeking to execute someone for failing to do so would be compromising for Haman. While Ahasuerus was increasingly functioning as a puppet for Haman, it was important that Ahasuerus not be alerted to that fact. It would be much easier not to mention Haman at all and to focus on the whole Jewish people instead. This would give the satisfaction of ultimate vengeance against an opponent, while also protecting Haman from uncomfortable lines of questioning.

Mordecai’s refusal to bow makes a bit more sense when we consider the possibility that, being privy to the daily conversation of the courtiers, observing the radical change in the royal court, and the rising cult of rule surrounding Haman, he rightly regarded Haman as illegitimate, as an unfaithful servant, and the homage he was demanding as verging on idolatry. He knew that Haman was quite untrustworthy and perhaps suspected that the supposed word that he had received from the king that all the king’s servants must bow to him was not in fact accurate, or was obtained under false pretences. In refusing to bow to Haman, Mordecai was actually being the one faithful servant of the king and kingdom.

The other courtiers knew Haman’s character. However, not bowing was very dangerous and would jeopardize their own safety and career prospects. Perhaps Mordecai’s resistance made their consciences feel uneasy. Perhaps it raised the possibility of unsettling questions being raised about their own loyalties, were the situation to become known to the king. Mordecai had already revealed one plot: what if he were one day to expose Haman? They needed his complicity. Although they claimed that it was ‘the king’s command’ that was being disobeyed, they knew better than to tell the king himself. Haman was known to play fast and loose with the king, not telling the king things that he needed to know, obtaining things under false pretences, using the authority of state for his own personal advancement, and likely misrepresenting the word of the king to others. Like Joseph in the house of Potiphar, Mordecai was faithful to his master by resisting an unfaithful second-in-command. As Joseph’s fellow servants sided with Potiphar’s wife, likely out of fear, envy, and resentment, so Mordecai’s fellow servants informed Haman about his resistance.

As I have already noted, several aspects of this hypothesis are quite speculative. For instance, while we know that Mordecai had firsthand awareness of rebellion in Ahasuerus’s court, the text gives us no suggestion that Mordecai knew that Haman was secretly planning a coup. Nevertheless, when we consider the way that Haman’s later actions reveal his character, manner of rule, and ambitions, I believe that we are quite justified in wondering whether Mordecai recognized these things in advance. If he had done so, his rebellion might seem to have been justified. Besides Haman’s own character, we should also consider whether his rapid elevation over all others represented a shift to a form of government in which a totalitarian concentration of power produced excessive demands for homage that were tantamount to idolatry.

The book of Daniel, in the stories of the fiery furnace and of the lion’s den, gives accounts of governments whose rulers demanded totalitarian subservience and honour, which the faithful resisted. Notably, the story of the lion’s den is also a story of something akin to an internal coup, where rivalrous and resentful officials sought to make the king a puppet in their scheme to remove Daniel. The true faithful servant is the one who won’t grant the king or any of his officials undue honour, while honouring them in all else. Perhaps the faithful servant is also a man who is prepared to resist the king’s word when he knows that it has been unrighteously obtained with the intent of subverting the king’s will.

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ Mere Fidelity has released episodes on the use of gendered language for God, on quitting social media, and on the cross and empty tomb in preparation for Holy Week.

❧ The Theopolis Podcast’s Deuteronomy series enters its second year, with episodes on Deuteronomy 23: Slaves and Cult Prostitutes, Deuteronomy 23: Interest and Loans, Deuteronomy 23: Vows and Scrumping, and Deuteronomy 24: Laws Concerning Divorce.

❧ Patrick Schreiner joined me on my personal podcast to discuss his wonderful new book, The Transfiguration of Christ: An Exegetical and Theological Reading. While this might seem like a strange topic to discuss on the brink of Holy Week, we argue it is in the light of the Transfiguration that Holy Week makes its fullest sense.

❧ I was invited back on the PloughCast to discuss the resurrection in the Old Testament with Susannah. You can listen to or read our conversation here.

❧ On the latest God’s Story Podcast episode, I discuss Revelation 20, among other things giving my understanding of the millennium.

❧ People constantly ask where the boundaries and the brakes for the sort of reading of Scripture that I espouse are to be found. In my latest series of videos for Theopolis I take up this question.

Interpretive Maximalism: Are There Brakes?

Controls and the Letter of the Text

❧ Both the Guilt Grace Gratitude (video) and Danvers Audio podcasts invited me on to discuss my forthcoming Davenant Hall course on Male and Female in Modernity.

Upcoming Events

❧ Alastair’s next Davenant Hall course is now open for registration:

Christian teaching regarding the sexes has grown in prominence as a source of controversy both within and without the church over the past century. Yet these debates often devolve into hurling around proof-texts, straining the gnats of first-century context, and contesting abstract ideas about rights, progress, and equality. What all sides often fail to consider is how much the material changes of modernity have affected this whole topic.

This course will consider ways that the transformed material realities of the modern world and its associated ideas have altered both how we understand ourselves as male and female, as well as how sexual relations are practised and conceptualized more broadly. By examining the greater felt incompatibility between scriptural teaching and social reality and practice, considering topical issues and live debates, and engaging with important texts, it will propose ways in which we can thoughtfully and faithfully understand, adhere to, and communicate Christian teaching in the twenty-first century.

❧ Alastair will be out in the Bay Area in late April, delivering a two-day course on a biblical theology of the sexes: Beyond Rules and Roles. You can sign up for it here.

❧ Most of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Susannah and Alastair

Glad to see I am not the only one (to my wife's utter despair) who has a multitude of not-yet-thrown-away laptops and phones...!

Congrats on the move!

The Haman hypothesis does seem to fit the overall text better than Jordan's. Thanks for this.