Dear friends,

Alastair: As I write this, I am seated in Terminal 3 of Heathrow Airport, waiting for a flight to New York JFK. Due to some suboptimal travel planning, [Susannah: this is a deliberate snark at me, though frankly a justified one because I booked my flight over without organizing it with Alastair even though I KNEW he was coming over too; it was pure absent mindedness] Susannah is on a different flight to the same destination in a different terminal of the same airport, her flight leaving and arriving within half an hour of mine. After our incredibly enjoyable layover in Oslo over a year ago, we had planned to do more layovers, but, partly due to time constraints due to work commitments and the fact that we have often travelled at different times, we have yet to do so again. [Susannah: I’M SORRY, I said I was sorry! Good grief.]

Our latest post, our review of 2023, was published only a few days ago, but, as this stint in the UK is going to be interrupted for a fortnight, I thought it would be good to give a proper update (our previous update was on December 18th).

Christmas this year was in Stoke-on-Trent, where we enjoyed time with my family. My brother Jonathan, his wife Monika, and their two children came over from Germany to spend the season with us and my brother and my sister-in-law in Manchester met up with us on a few occasions over the period. Jonathan and Monika and the kids return to Germany today: a sudden and perhaps even unwelcome peace will doubtless descend upon my parents’ house in all our absence!

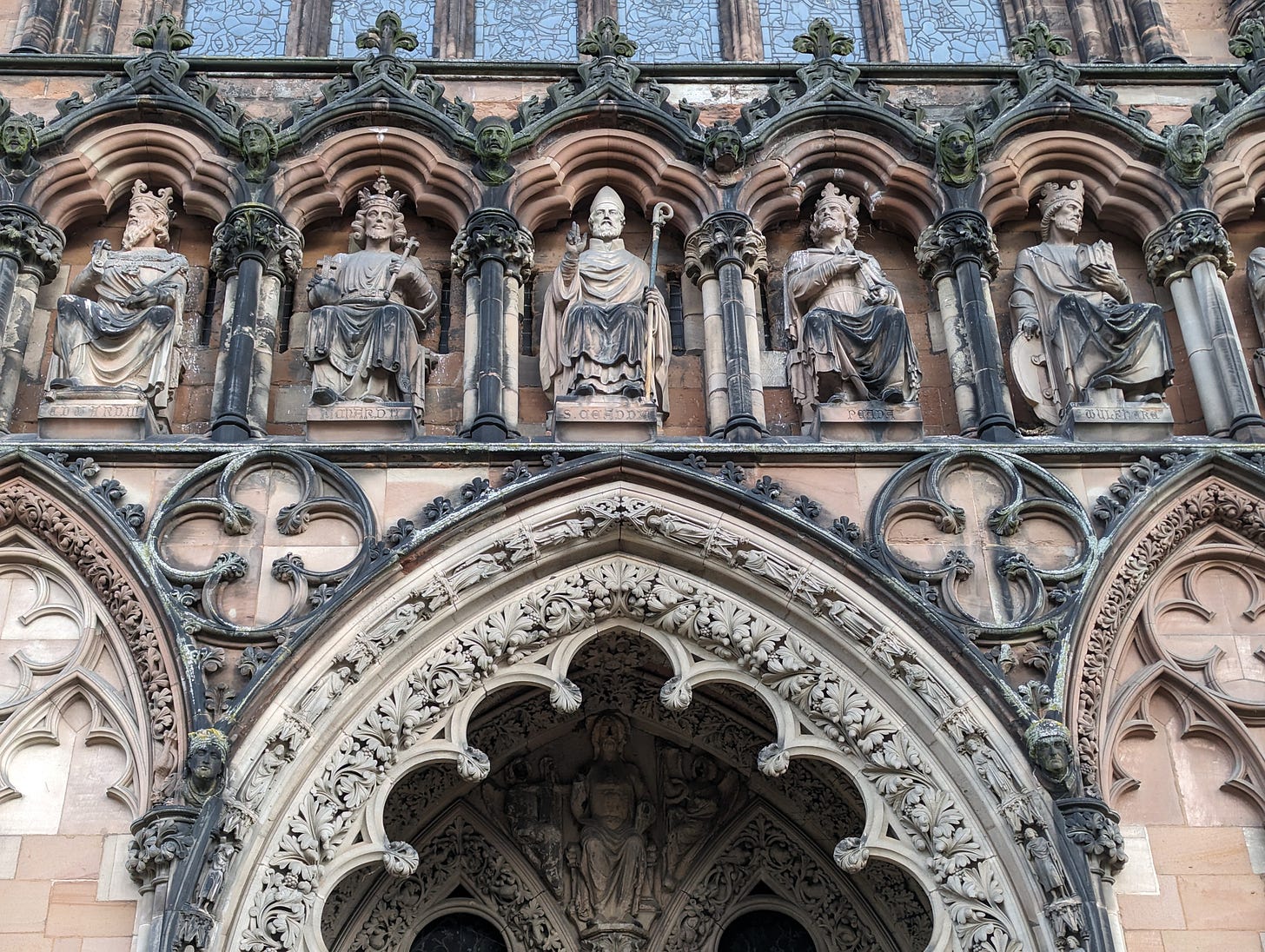

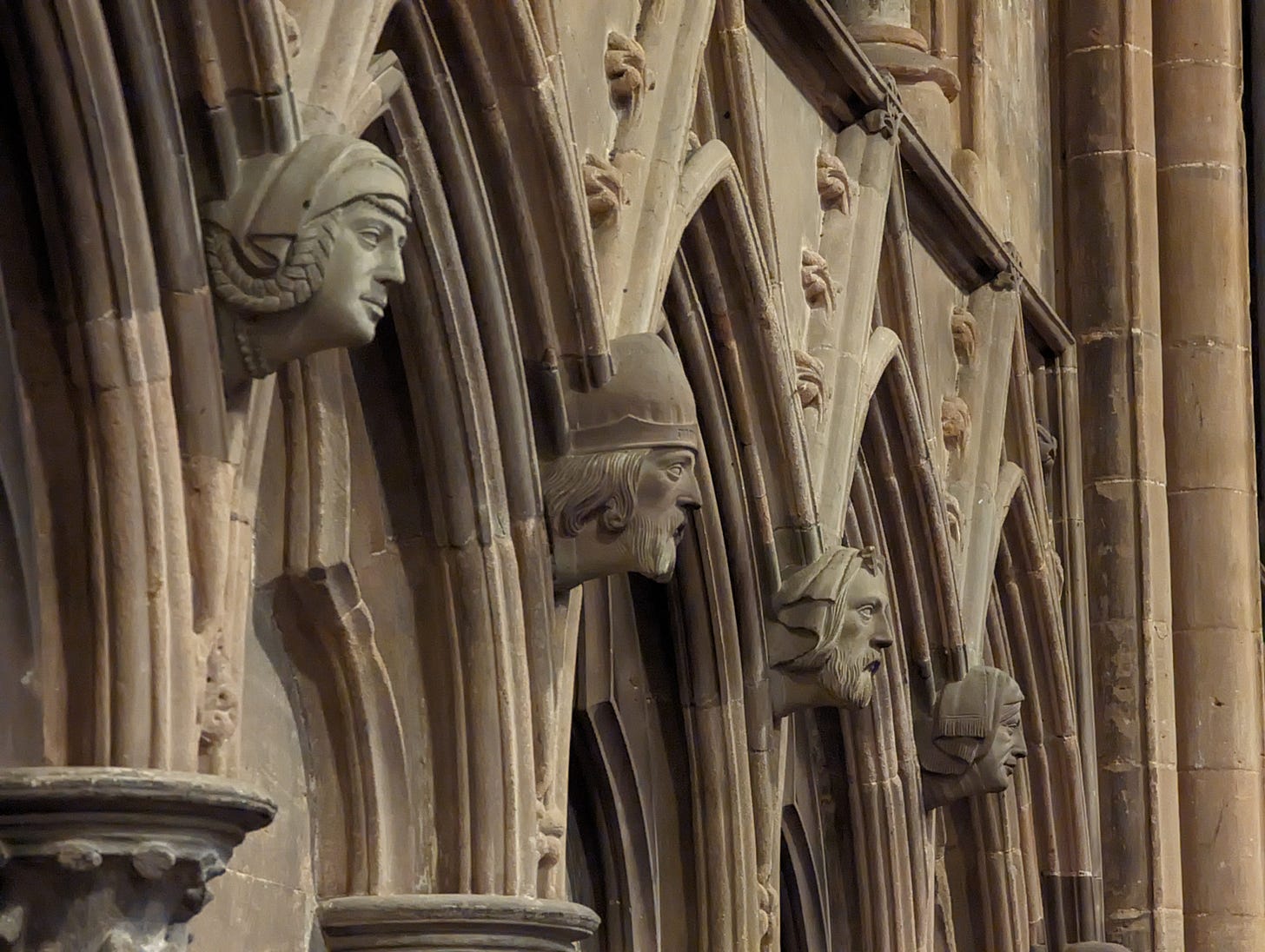

On Christmas Eve, I took Susannah to our diocesan cathedral—the Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary and St Chad—in Lichfield for her first visit for a carol service. It was the crib service and clearly intended principally for families with young children. It was delightful, even though I don’t remember a ‘Christmas fox’ in the nativity stories in the gospels (a cheeky chappy who gives his heart to the newborn Jesus). [Susannah: We went with our niece, who at eleven felt herself much more grown up than the younger children in costumes; but she still loved them, especially the baby dressed up as a star. The other major favorite costume was little girls dressed as Mary, at least one of them in what looked like an Elsa costume, because she has a blue dress.]

The Cathedral of the Virgin and Chad is quite spectacular and, although we didn’t get to look around properly either within (as the service was going on) or without (as the sun was going down as we left and it began to rain), it was great to see it again.

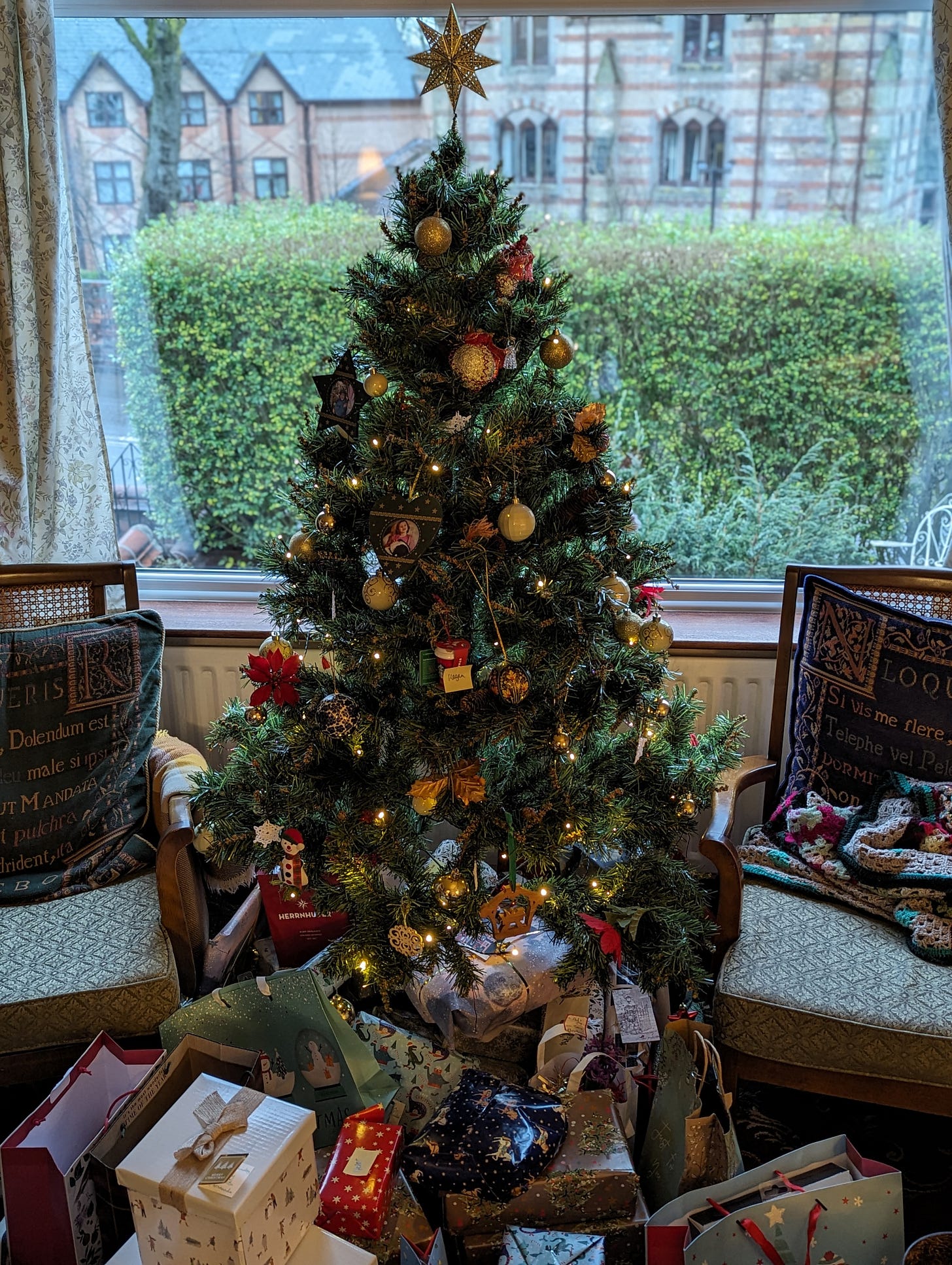

Christmas Day began with our traditional family breakfast, with a couple of Swedish tea rings, followed by a church service. Most of the rest of the day was exceedingly relaxed, with some neighbours coming over to talk and share desserts with us, the opening of presents, and lots of eating and chatting. It was truly delightful, and it was a blessing to have so many of the family there.

My father’s health continues to deteriorate with his advancing Parkinson’s Disease. He received a new chair just after Christmas that seems to be far better at keeping him from slumping over and also enabling him to stand up. It performs a variety of impressive operations and my father has had considerable fun playing with it learning how to operate it. Due to his limited mobility, we were not able to go out for walks with him, but we spent a lot of time sitting and talking with him in the living room and joined everyone to watch some films with the kids in the evenings after work—Miyazaki’s Laputa: Castle in the Sky and The Railway Children, a favourite from our childhood.

Having watched Castle in the Sky, a few days later a group of us went to Manchester to meet up with some friends and watch Miyazaki’s latest, The Boy and the Heron. It is perhaps one of the more thought-provoking of Miyazaki’s movies and one to which I shall definitely return.

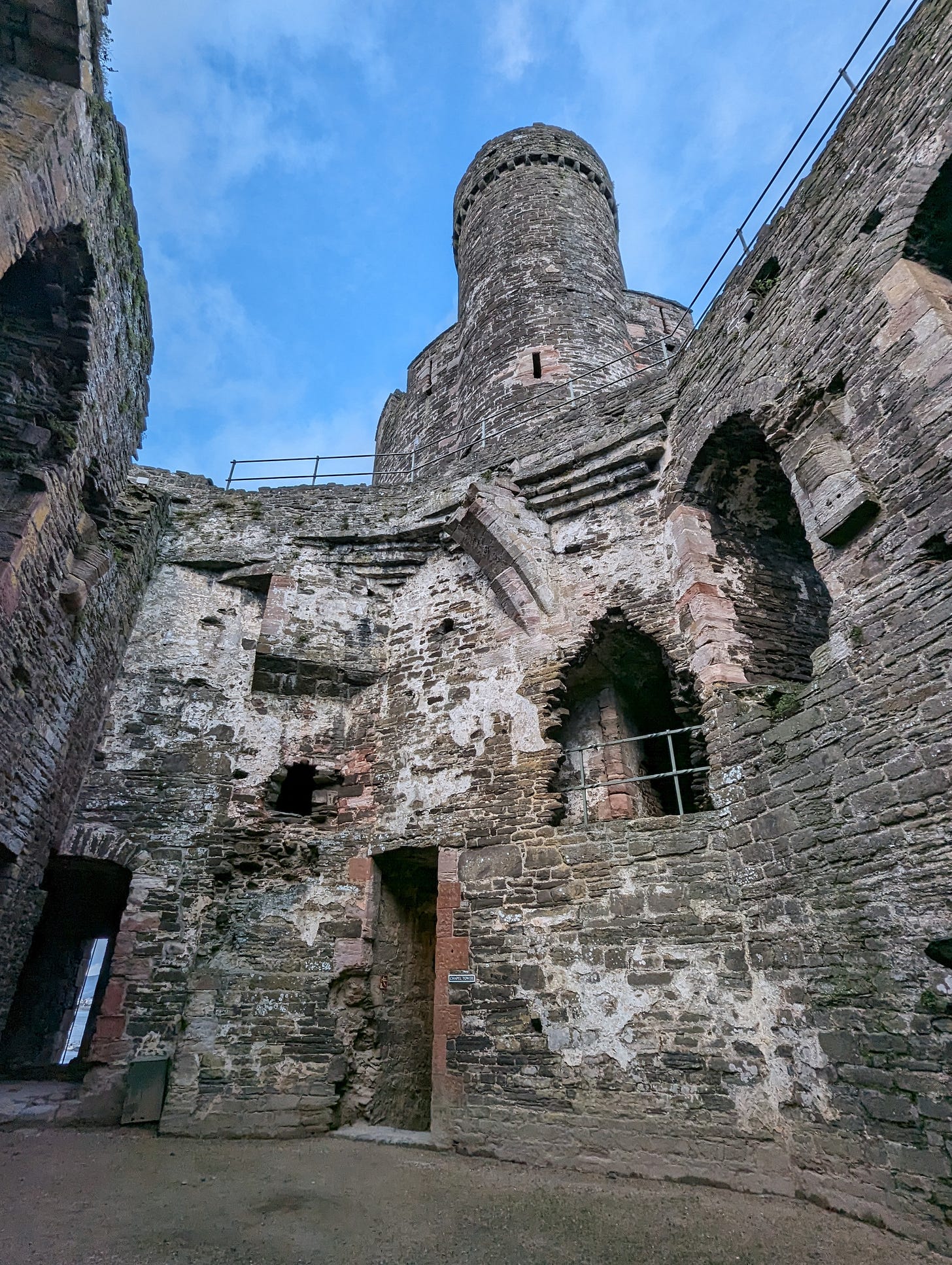

I had another outing with Jonathan and Monika, the niblings, and some friends to Conwy. Susannah had too much work on and was not able to join us. [Susannah: I regretted this decision the instant they drove off.] Conwy is a Welsh walled town, with one of the more impressive castles in the UK within it. You can climb most of the towers, which provide a commanding view out over the bay. As we had heavy rain shortly before we arrived, we were expecting inclement weather for the day, but it turned out to be quite pleasant. I had not explored the castle on previous visits to the town, so I enjoyed looking around it.

On the way back, we stopped off in Llandudno for a meal.

Just under a week before Christmas, I received forty balls of wool for my latest knitting project, a large nautically-themed blanket, upon which I have been working consistently since. It is massive, perhaps the largest project I have attempted to date. After knitting through much of Christmas Day, through some films and TV shows (The Lion in Winter and some classic Tom Baker era Doctor Who, in addition to the ones mentioned above), through some podcasting, and several conversations, I am over halfway through. I’ve had to leave it at home and am already itching to return to it. Meanwhile, Susannah has been crocheting lots of items as gifts for friends and family. [Susannah: Special offer for our subscribers: if you would like one, contact me on Twitter, and I would be happy to make you something like a hat!]

I preached at our church on New Year’s Eve. A member of the church, a gifted amateur artist, had painted a wedding portrait of me and Susannah, which he gave to us. It really is extremely impressive work (and hard to capture fittingly in a photo) and a most wonderful gift! On the way back from church we also run into a local lady who exercises her parrots in the park and had a long and fascinating conversation with her.

We spent the rest of New Year’s Eve around with my family, talked about the year that was passing, and prayed together about 2024. We then went to an elevated spot to watch fireworks bringing in the new year.

The rest of the Christmas period involved several morning meet-ups in Starbucks with our niece and a visit from one of my uncles and aunts, with two of my cousins with their families.

We took the train down to London yesterday morning and hung out in the city, getting some work done in Foyles and then taking an hour and a half to look around the World War I part of the Imperial War Museum. I had not visited the Imperial War Museum since I was a teenager and Susannah had never visited. An hour or so was not as much time as the museum merited: we will definitely be back again as some point soon. [Susannah: I am feeling strongly that I’m about to enter into another Churchill and WWII spycraft phase.] Last night we stayed with some friends, played Carcassonne and talked theology long into the evening! This morning and early afternoon we wandered around London, trawled second-hand bookstores, before heading to Heathrow.

I’ll only be in New York for a couple of days: most of my time on this trip will be spent in Birmingham for the Epiphany Term of the Theopolis Fellows Program and at Davenant House in South Carolina. However, it will be good to spend the very tail end of Christmastide in New York.

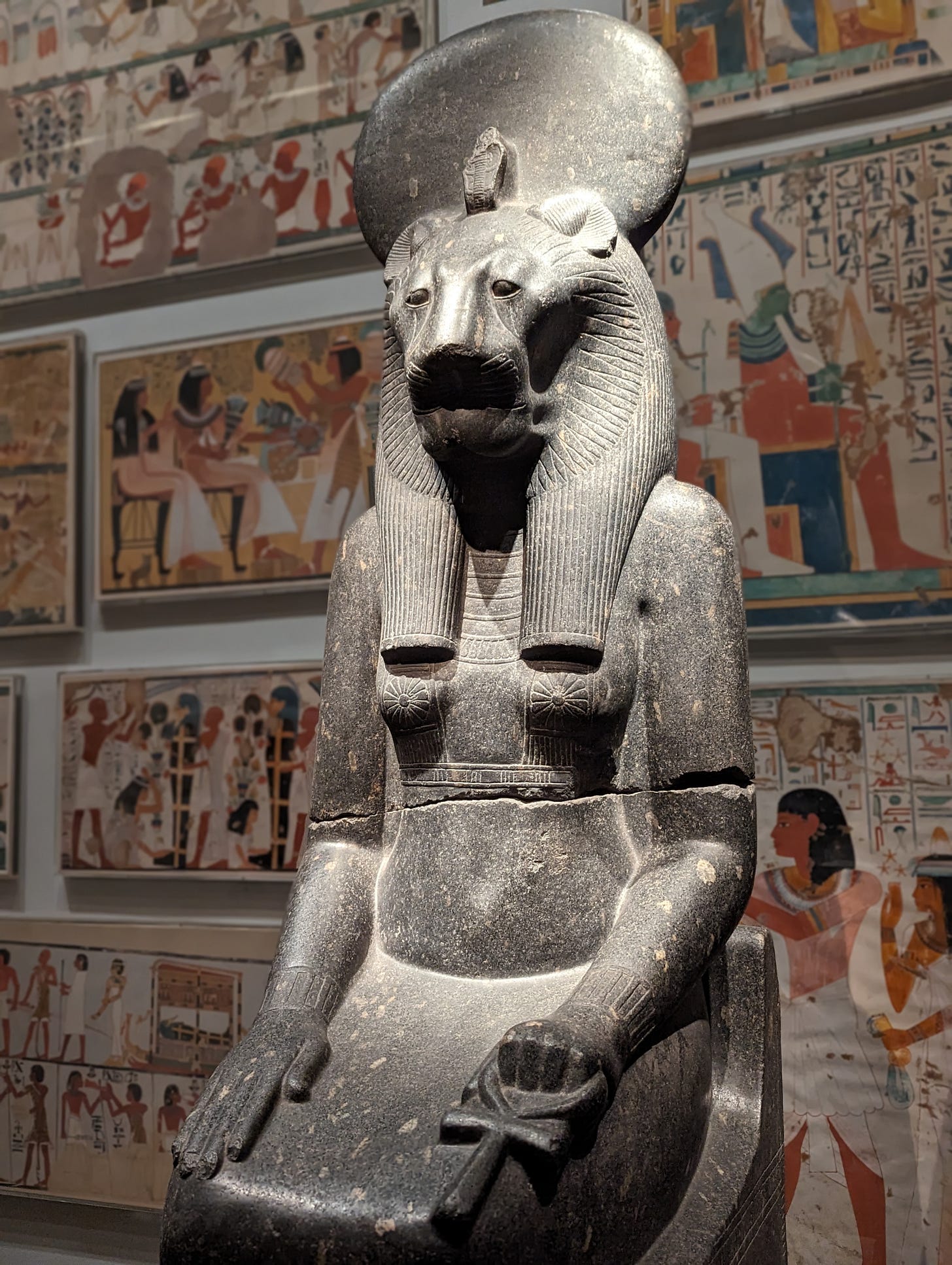

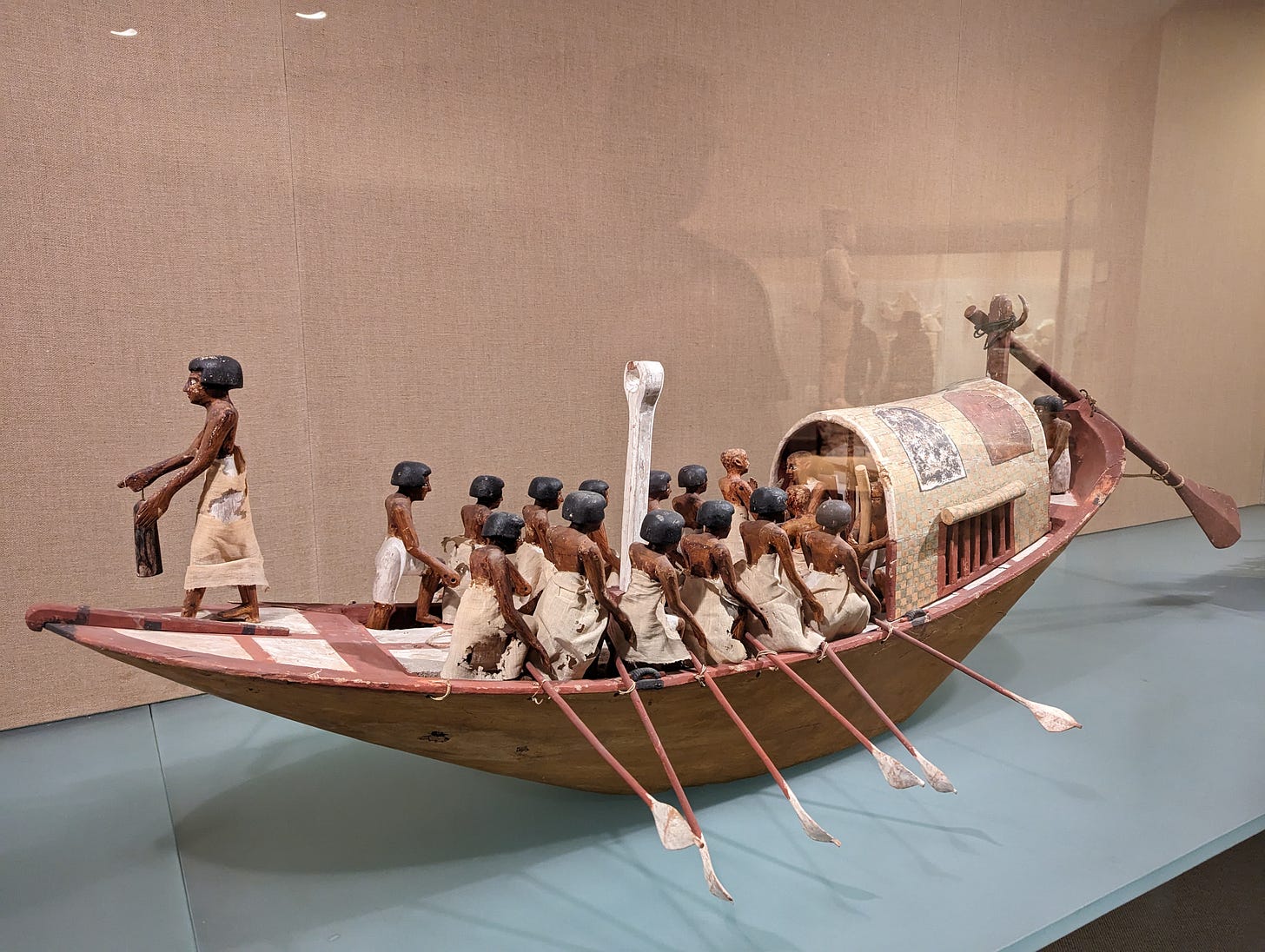

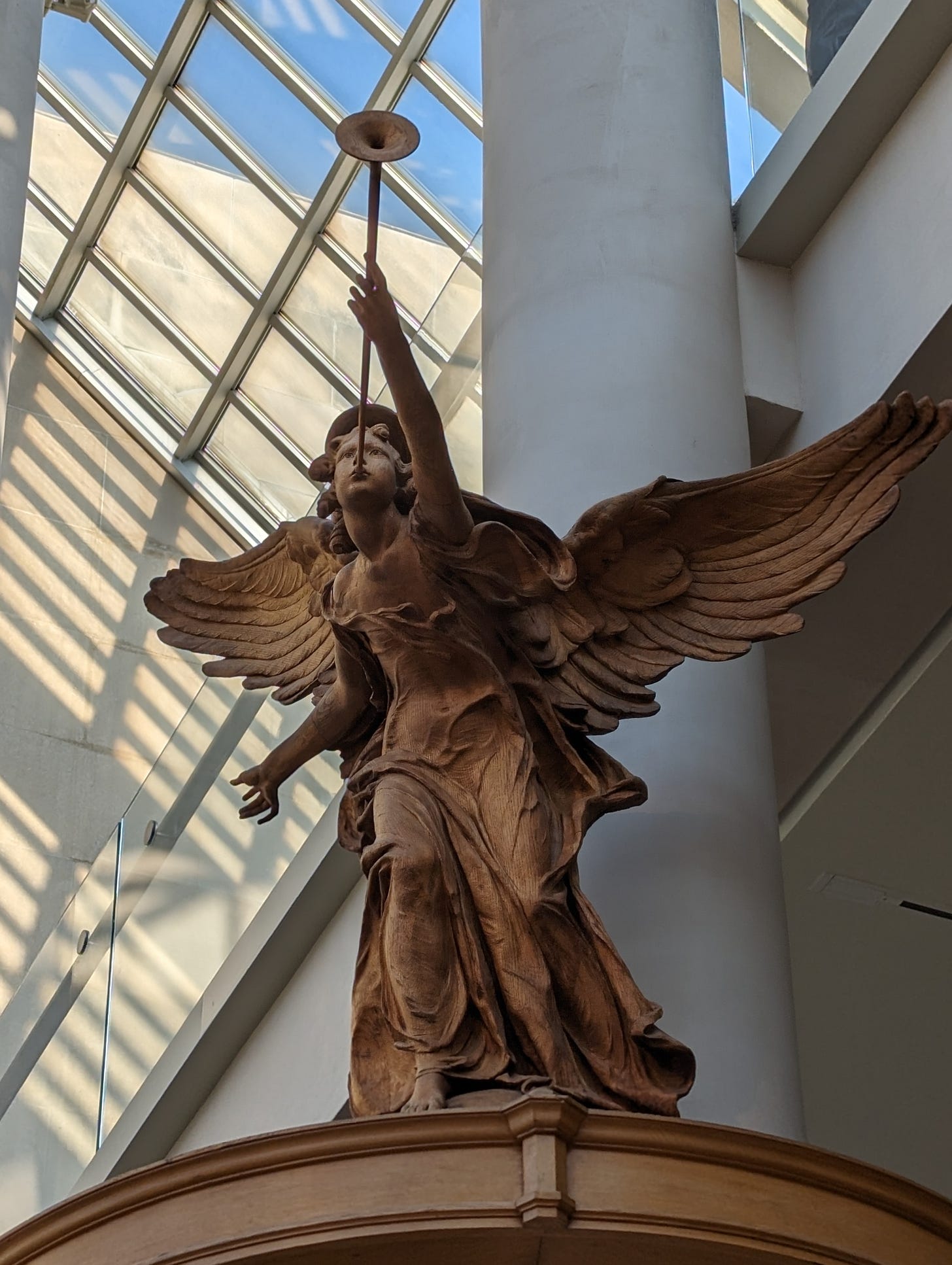

Update: We are now back in NYC and it is twelfth night. I spent the afternoon wandering around the city with a supporter who is visiting it for the first time. We went to the Met Museum of Art, walked around Central Park, introduced him to some NYC food, and went to a bookstore.

The Met Museum is always incredible to visit. It is a short walk from our apartment, but I do not usually have the time or occasion to visit. Every time I do go there, I leave intending to do so more often.

Susannah: It was a truly magical Christmas, one in which we felt very strongly God’s presence in the ordering of our lives. Seeing Alastair’s dad’s health worsen is difficult, but seeing his response to that—a kind of gallantry, a trust in God even in his weakness—is inspiring. It was wonderful to have the clan at least somewhat gathered for the holiday, and to see him enjoying his children and grandchildren. Phil, even in his weakened state, continues to connect people he thinks should be in touch, and that too has been a major blessing for us.

Alastair’s parents had probably 70 Christmas cards from friends this year, which Joy ranges around the crown molding at the top of the dining room, just as my grandparents used to. Seeing that material picture of a life of friendship and Christian connection was also inspiring: I’m not sure we’ll ever be able to get millennials to send Christmas cards at the level of boomers, but we can strive to be the kinds of people who would receive those cards. And we did get some!

Megan and Jeremy, our 11-year-old niece and 14-year-old nephew, are just delightful people, and very prone to the kind of teasing that is a love language in my own family, so we had an absolutely wonderful time with them.

Last year was the first Christmas that my brother and I were both married, and everyone was gathered in New York; this year, by sheer mathematical necessity, Toby and Langan and Alastair and I were at our respective in-laws, which left our own parents as Christmas orphans! Which seems like a problem in logic somehow: if every family that celebrates Christmas wants to get all the siblings from Generation B (considering the parent generation to be Generation A) and their children of Generation C together for SOME Christmases, that must by necessity mean that every OTHER Christmas, 50% of all grandparents (i.e. Gen A) must be Christmas orphans, which seems tragic!

And by the logic of in-laws, the decision of each family must coordinate with the decision of every family to which they are linked by marriage, which if our family is anything to go by rapidly gets you into the mutual coordination of many layers of in-laws on many continents. I find this to be a fascinating puzzle and the only solution I can think of is for Protestants and Catholics to aggressively marry into Orthodox families, given that they celebrate Christmas on what for us is around Epiphany. Please let me know if I’ve made some kind of error in calculation.

Many blessings to you all this New Year—we have so much to do, and we’re extremely excited to do it, and to tell you all about it.

A Name and a Blessing

In Genesis 32, we find the patriarch Jacob at a critical point in his story. He is travelling back to the land of his father after many years absence and does not know what awaits him upon his return. When he had departed from the land of Canaan, he had done so because of the threat posed by his brother, Esau, who had wanted to kill him. Now Jacob was going to have to face him again. He did not know whether his brother’s anger had diminished in the many intervening years.

The chapter begins with Jacob sending messengers to the land of Seir, seeking peace with his estranged brother. Yet the messengers return with a dismaying report: Esau is coming to meet him with four hundred men, Jacob can only presume with the intent to attack him.

Jacob is naturally greatly afraid and distressed. He sees likely disaster approaching and lacks the power to meet it. Recognizing the real threat of losing his entire family, he divides them into two camps: perhaps if Esau were to attack the one, the other might manage to get away.

So begins the longest night in Jacob’s life: a night of fear, dread, and desperate uncertainty. What the morning holds is yet unknown, but Jacob knows that his life and his destiny hangs upon whatever happens next and that matters are largely out of his hand. There is no way back and a terrible threat seems to lie ahead. Darkness descends upon him: a black and starless night shrouds the land and the cruel shadow of death moves over his soul.

These events come at the turning of a key page in Jacob’s life, at the ending of one chapter and the start of a new one. Indeed, in ways that Jacob could never have foreseen, the entirety of his life to that point would come to a head that evening. The Jacob who limped into Canaan and readied to meet Esau the following morning would be a different man.

Jacob’s life was a difficult one, marked by struggle. He had struggled with his twin brother in the womb. Born second, he came out of the womb clutching Esau’s heel. Rabbi David Fohrman suggests that the contrasting descriptions of the naming of the two infants in Genesis 25:25-26 might indicate that Jacob’s name was an unflattering one that he received from his father alone, in contrast to his brother’s, which he received from both of his parents.

Isaac, their father, had always favoured the elder of the twins. Esau was ‘a skillful hunter, a man of the field’ (Genesis 25:27), seemingly possessing aptitudes that were lacking in Jacob and winning him the favour of Isaac, who enjoyed the game that Esau hunted. Jacob had not meekly accepted the situation. He had taken advantage of Esau’s unconcern with the covenant vocation that was to fall upon the shoulders of the heir of Isaac and taken his birthright. He later deceived his father to obtain the blessing intended for his brother.

When he fled from his murderous brother to Paddan-Aram, he sojourned with Laban, his uncle, who had tricked, wronged, defrauded, and diminished him in status. Most notably, having promised Jacob his daughter Rachel, Laban had switched Rachel for her older sister, Leah. Jacob had to serve his uncle for two decades. While the Lord prospered him and gave him many of the possessions of his uncle, Laban had treated him as a stranger and a servant, rather than as a nephew and son-in-law. In the end, Jacob had to escape from his uncle’s house and was pursued and overtaken. The previous chapter had concluded with a pillar and heap being established as witnesses and boundaries between the two men and their households.

To that point, Jacob’s life was dominated by three adversaries. By his father, Isaac, who, from Jacob’s birth, had favoured Esau over him. By his brother, Esau, his great rival, whose birthright he had taken and whom he had tricked out of his blessing. By his uncle, Laban, who had caused misery in his house by giving him an unloved wife, whose own sister became her rival. Laban had also defrauded, wronged, and had reduced him to servitude.

That night Jacob was caught between Laban, who had pursued him and to whose land he could not return, and Esau, the brother who had wanted to kill him and was on his way with four hundred men. The defining struggles of Jacob’s life were all in the foreground that night.

If we were to identify two key things that were at the heart of Jacob’s struggles, we couldn’t do much better than to focus on his desire for a name and a blessing (noted by Fohrman). Jacob’s unflattering name came after his struggling in the womb with Esau, who came out first and stronger. The blessing was the next great thing. The blessing, which represented for Jacob the covenant legacy and destiny, was going to Esau. Jacob struggled with Esau for that, eventually deceiving his father to obtain it.

A name can be a powerful thing. It can speak of the origins of a person, but also of their place and role within the world. It reveals what a child means to its parents and what destiny they see as marked out for it. It can be an assurance of belonging and to name someone is one of the most fundamental acts of recognition.

A blessing is an assurance of purpose, destiny, and positive outcomes in a world of uncertainty and struggle. Like a name, it can be a sign of recognition and good favour.

Throughout Jacob’s life, his nearest male relatives—his brother, his father, and his uncle—had all been adversaries and obstacles to his achievement of these things. His father would not recognize him, treated him as a weak and unfavoured son, and had intended to give the entire blessing to his brother. From the womb on, Esau had been his rival, with whom he had struggled. Esau’s murderous rage had caused Jacob to be driven away from his home and family into exile. Jacob might have hoped for welcome from his uncle, to be treated as one of his family, especially when he wanted to marry Rachel. However, Laban denied him the recognition of family and, rather than bless him and show him good will, had opposed, wronged, and reduced him.

Jacob’s life had been a life of wrestling, a life of wrestling for a name and a blessing.

Genesis 32 contains two wrestling stories; the first begins in verse 9, as Jacob prays, much as our Lord prays in Gethsemane prior to his arrest and crucifixion. In his prayer, Jacob appeals to God’s promise; he also returns to it at the end. He prays only for the preservation of his life and the lives of his family and is prepared to surrender his possessions. Everything that Jacob had gained he had gained from the Lord’s hand. The Lord had given, the Lord can have back. Jacob was also confident that the Lord could restore those things to him again.

It seems likely that Jacob settled upon his course of action only after having prayed. He sent waves of gifts ahead to Esau. Although all indications to this point would seem to suggest that Esau means to attack him, Jacob determines to try to pacify his brother.

Jacob sent his family on ahead in four different companies, remaining behind alone. He had surrendered everything he owned and his entire family into the hand of providence. His possessions and family were travelling towards a brother who had sought his life and was coming towards him with an army. At this point Jacob is divided in two, stripped, and cut into four pieces.

[There is a sacrificial dimension of these events that should not be missed. The etiological detail with which the account of Jacob’s wrestling will conclude—that the Israelites do not eat the sinew of the thigh that is on the hip socket on account of the Angel touching Jacob at that point—strengthens such sacrificial associations.]

Alone in the pitch of the night, Jacob is attacked by an unknown assailant. The reader has been braced for the encounter with Esau and perhaps even been prepared for a reappearance of a vengeful Laban, but this mysterious figure is not someone we were anticipating. When the encounter with Esau happens in the following chapter, it will be apparent that the true resolution of Jacob’s story occurred at this earlier point and that the encounter with Esau must be interpreted in light of the earlier wrestling with the Angel.

As dawn approached, Jacob’s attacker touched the hollow of Jacob’s thigh, near his genitals, putting it out of joint (the association of this place with both reproduction and blessing/oath must not be missed, cf. Genesis 24:2-4; 47:29). Nonetheless, Jacob refused to let the man go until he blessed him. Jacob seemed to realize that this figure was no ordinary man; in asking the man to bless him, he seemed to acknowledge his superior character.

The man went further than Jacob’s request: not only would he bless Jacob before he departed from him, he also gave the patriarch a new name, Israel (note that the very name of the Jabbok is a sort of confusion of Jacob’s own). This is the name that would be borne by the people that would descend from Jacob.

As commentators such as Fohrman and Leon Kass note, Jacob’s crossing the Jabbok and wrestling in the darkness was akin to a return to the womb, where he had once been locked in a struggle in the darkness with his twin brother.

The Jabbok is a transitional or liminal place for Jacob in other respects. Like other key water crossings in Israel’s history, the river or body of water marks off one realm from another, with the crossing being a passage through to a new realm. As in other stories in Scripture (perhaps the most similar of which is the story of the Red Sea Crossing and the most significant the story of Christ’s death and resurrection), the transition is associated with the movement from darkness to light. Indeed, one could suggest that the entire sojourn with Laban has implicitly been framed as a time of darkness, with a focus on events that occur in the darkness or at night. There is also a chiastic symmetry with the beginning of that sojourn, for instance in Rachel arriving as the one leading the final of four flocks, much as hers is the rear of the four companies that Jacob separated.

At the Jabbok, the Lord addressed Jacob’s two great desires for a name and a blessing, the things denied to him by Isaac, Esau, Laban, and others. With those desires addressed, Jacob no longer needed to wrestle with human rivals to obtain them as he had once done. In the next chapter, Jacob would allow Esau to go ahead of him and symbolically return the blessing that he formerly stole (cf. Genesis 27:27-29). He had not willingly permitted Esau to go ahead of him in leaving the womb of their mother. The contrast with earlier events is also evident in his ready declaration of his name to the Angel, about which he had lied to his father in chapter 27.

When Jacob says that seeing Esau’s face was like seeing the face of God (33:10), so shortly after his naming of Peniel after seeing God face to face (32:30), the reader is invited to grasp a connection. In wrestling with the Angel, Jacob had appreciated something of the deeper truth behind his wrestling with Esau, with Isaac, and with Laban. As James Jordan has argued, behind all these struggles was God himself, dealing graciously yet mysteriously with Jacob. Wrestling with the Angel provided Jacob with assurance of God’s greater agency in it all. Jacob had wrestled with God and with man, but, ultimately, even in his struggles with his kinsmen, it was with God that he was dealing.

With such assurance and granted a name and a blessing from God himself, Jacob was enabled to approach those human rivalries differently. No longer did he need to wrest a blessing from a resistant father or steal a birthright from a degenerate brother. The Lord himself would give Jacob these. It was with God that Jacob should wrestle.

This crucial passage in the Jacob cycle has been on my mind in the passage into 2024, which, perhaps even more than other years, has its uncertainties, threats, and attendant anxieties. Like Jacob, we need to develop a clear sense of God’s gracious agency in our lives, even in our dealings with enemies, opponents, and rivals. As Jacob’s son Joseph would later say of his suffering because of his brothers’ sin against him, ‘As for you, you meant evil against me, but God meant it for good’ (50:20).

Jacob, like Joseph later would, here arrives at an epiphany concerning the nature of God’s dealing in his life. These dealings might feel like the attacks of a mysterious assailant in the darkness, but as we recognize the identity of the one with whom we are dealing, even a seeming assault comes to be recognized as an occasion for extraordinary blessing.

Like Jacob, we also need to recognize that our name and our blessing ultimately comes from the hand of God. We do not have to obtain it by deceit or jealous rivalry. It is to him that we must principally look for recognition and security. With this recognition comes a new posture to our neighbour, freeing us from rivalries and antagonisms that once animated and embittered us and enabling us to act differently towards them.

May we all enjoy the transformation of life that flows from such recognition as we enter 2024!

Recent Work

Alastair

❧ Our latest Mere Fidelity episodes were an in-house discussion of the Theology of Blessings and a conversation with Peter Leithart about his new book, Creator: A Theological Interpretation of Genesis 1.

❧ The Theopolis Podcast’s series on Deuteronomy continues with an episode on Deuteronomy 22: A Man in a Woman’s Cloak.

❧ My series on the book of Revelation with the God’s Story Podcast continues with an episode on the seven bowls in Revelation 16 and the harlot and the beast in Revelation 17.

Upcoming Events

❧ The third UK Davenant Convivium will be on the 20th January, with Oliver O’Donovan as the keynote speaker.

❧ Alastair will be speaking on a couple of occasions during his time at Davenant House in South Carolina, but the details are not completely settled yet. Contact one of us if you would be interested in hearing him.

❧ The Davenant Institute was recently awarded a prestigious Lilly Endowment grant, which will enable us to establish a project designed to equip Christians for living in the digital age. Alastair will likely be doing a lot of work on this front in the next few years.

❧ Most of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Susannah and Alastair

Can’t believe that I am just now, in the Year of our Lord 2024, learning about a church named “The Cathedral of the Virgin and Chad.” Dying laughing. 😂

Alastair -- I was just listening to an old Mere Fidelity Q&A from last July where you guys tackle some thorny questions of gender. During that episode, Matt recommends that listeners pick up your book, Heirs Together. But this has proven to be pretty difficult. I’m not even sure it’s published? I wonder if he has just read an unpublished manuscript and forgot that it wasn’t publicly available? Or if it is available somewhere and I just haven’t searched in the right places?