№ 23: A Little Empathy

Also questions for attentive Bible reading. And the criminality of a spaniel.

Dear Friends,

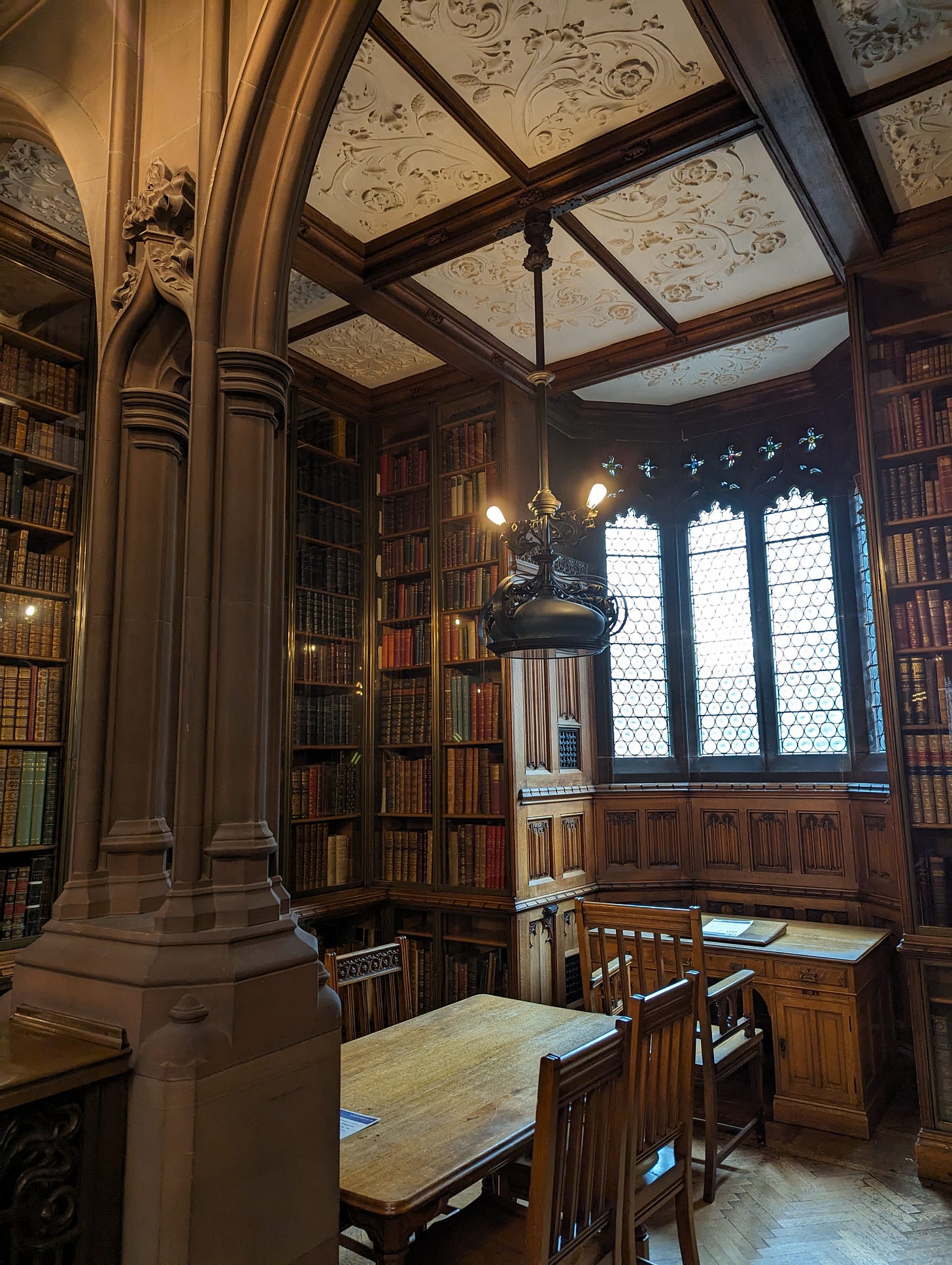

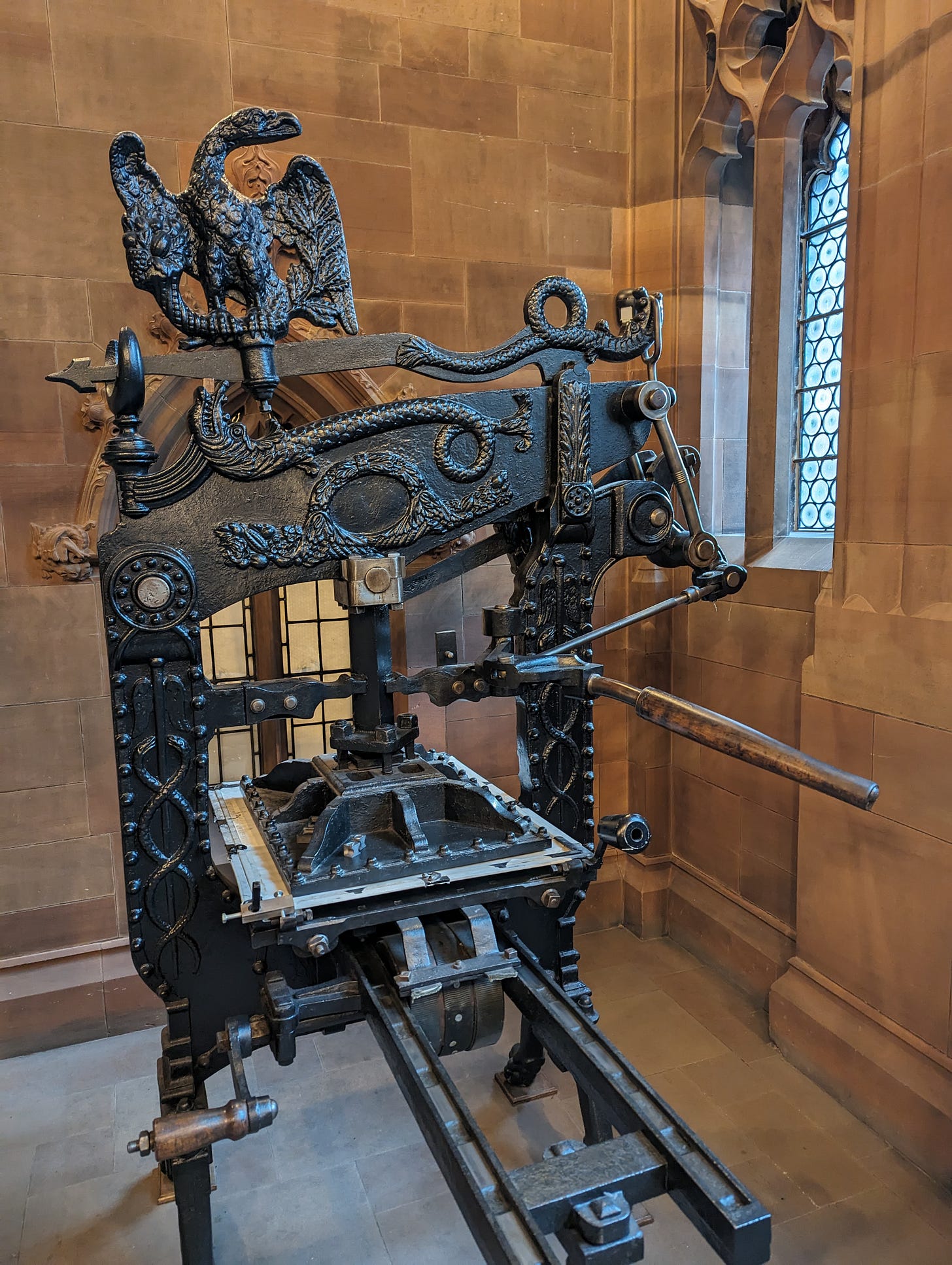

Susannah: Writing from the train en route to Durham, where we’ll be for the next week or so, followed by York and London. We broke our journey at Manchester and had an hour and a half before the next train, and Alastair suggested that we go to the Rylands Library. He’s been hassling me to go for years, and as usual I ought to have trusted him on this, because it is truly amazing.

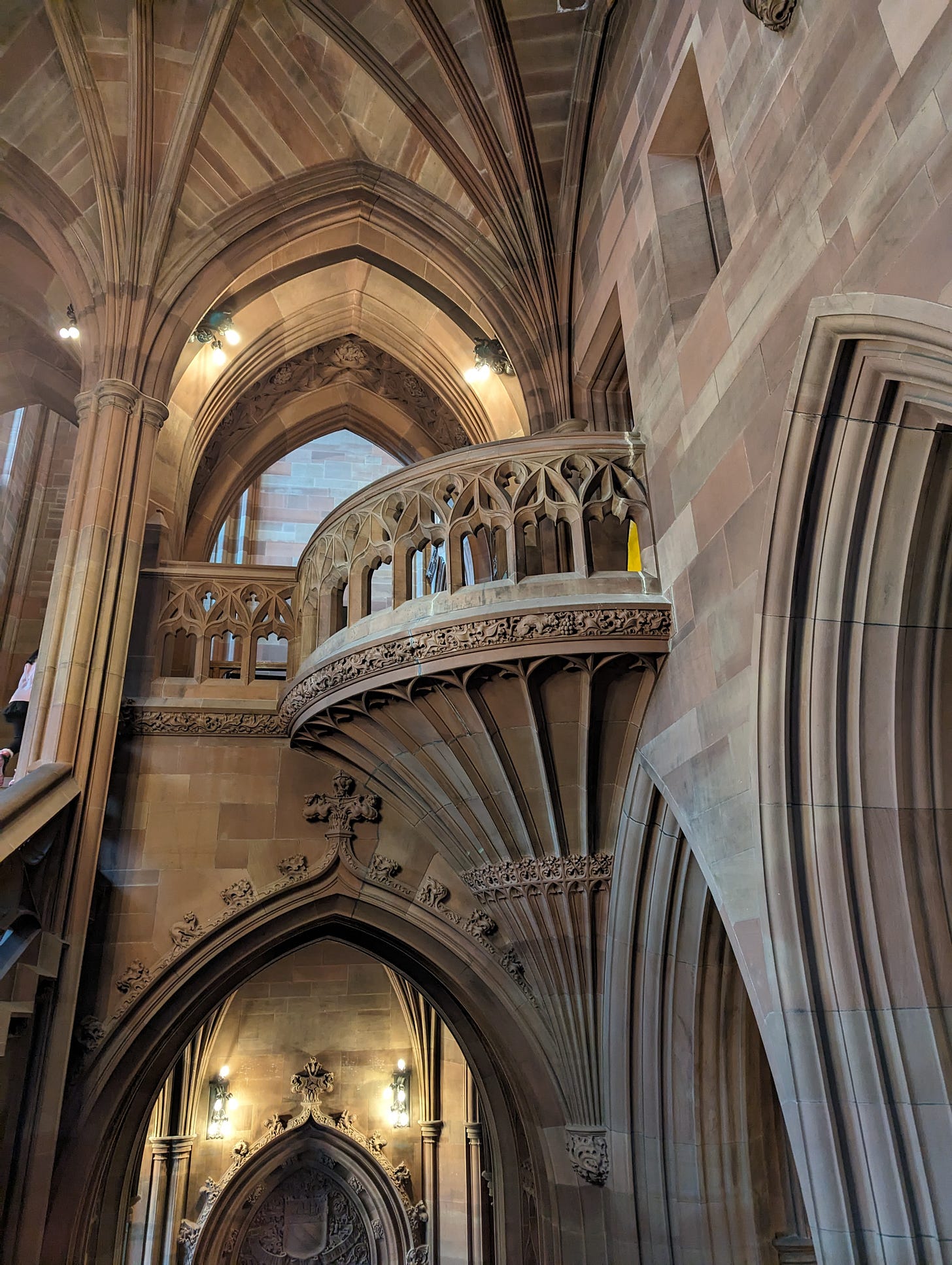

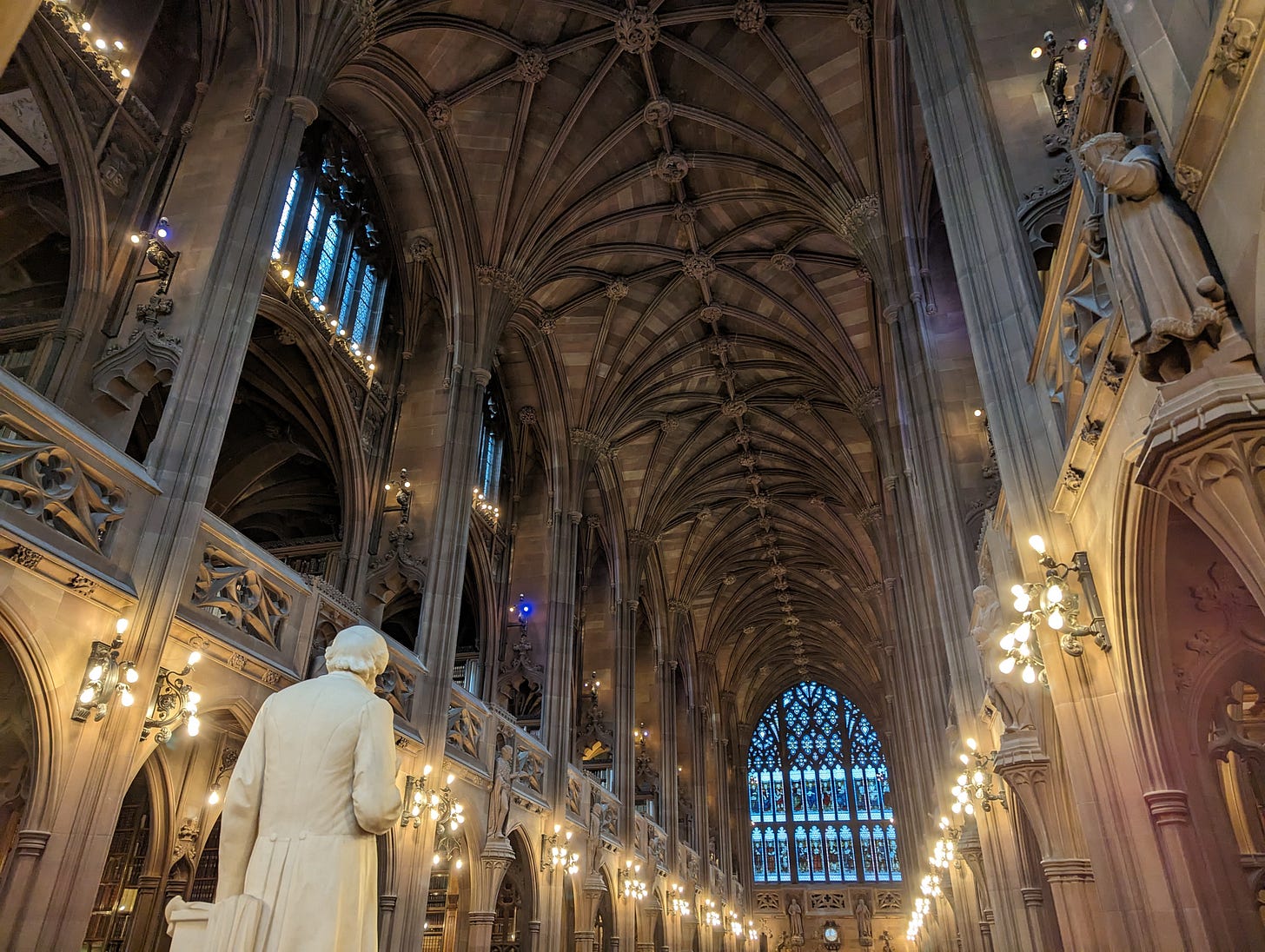

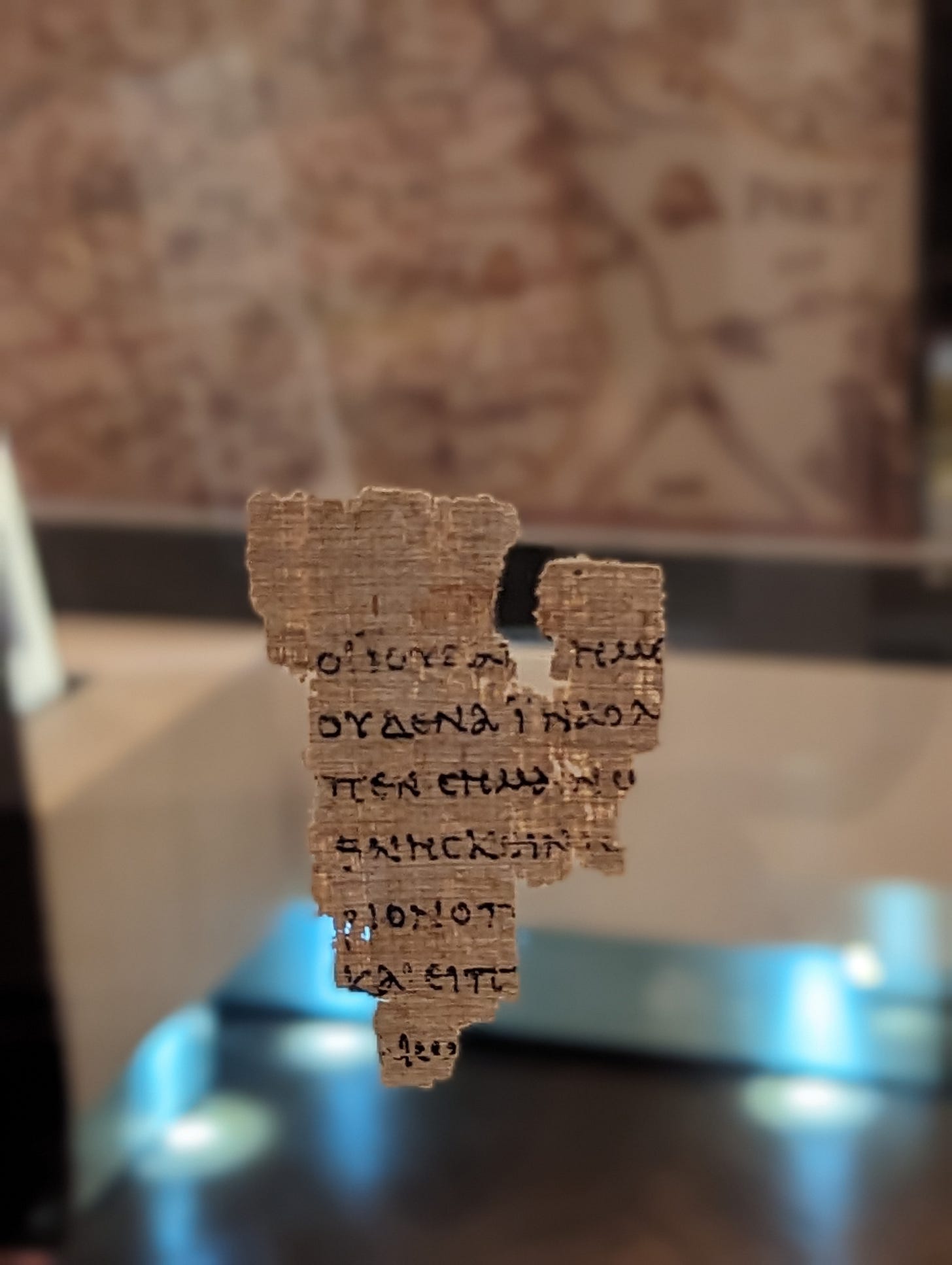

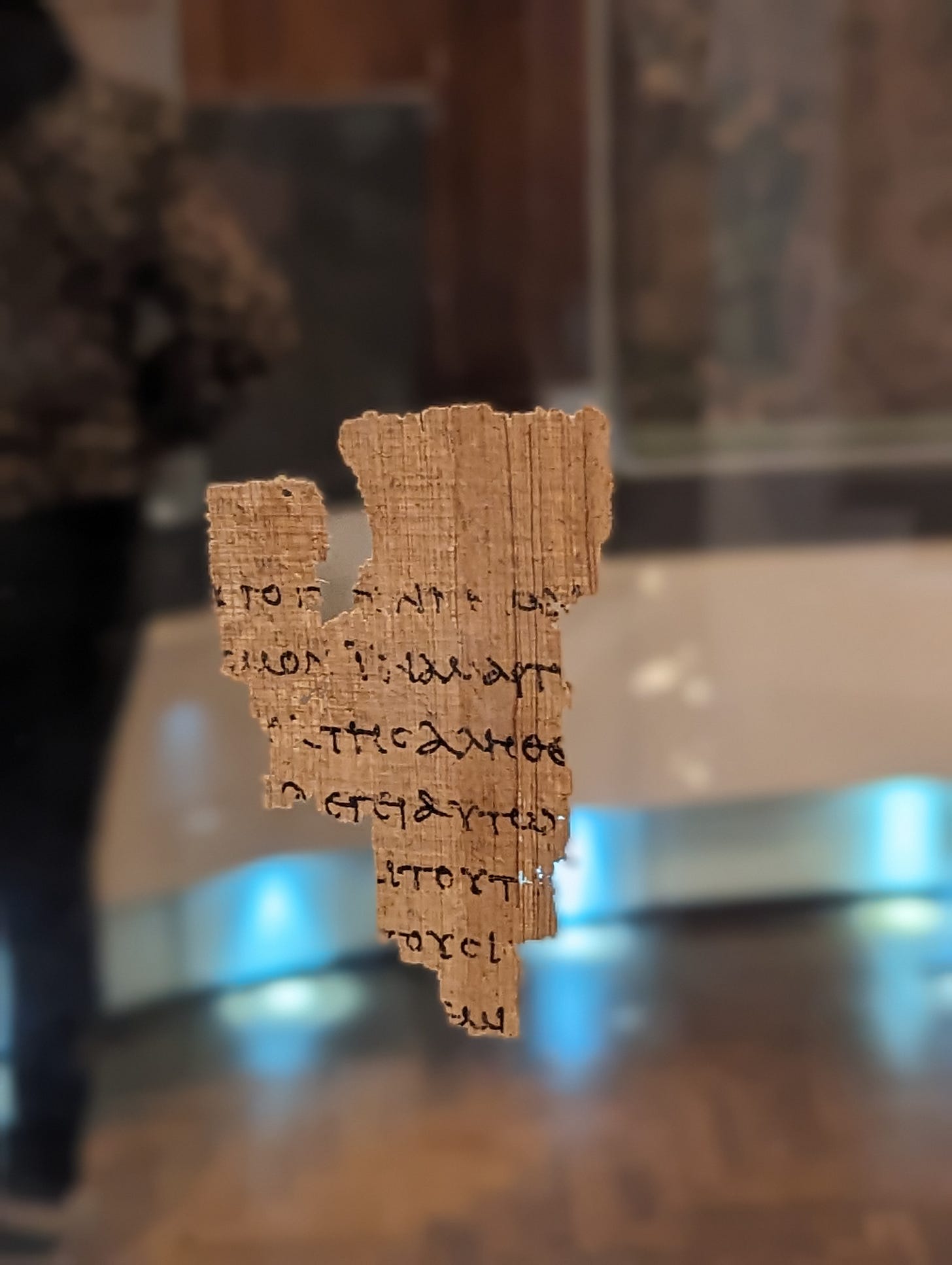

Imagine a building that is the physical embodiment of earnest Victorian Protestant Great Books-ism: clearly a kind of aspirational 19th century homage to places like the Bodleian, nearly 400 years younger but aiming at the same vision. It also has as part of its collection a fragment of the Gospel of John from the second or early third century AD. In other words it was produced within, hypothetically, 18 months and at most a couple of decades after John’s death in AD 99.

We’re very much looking forward to our time in Durham. I (Susannah) just got back from three days in London, where I entered into deep plots (for the common good!) in rooms that were not smoke filled only because that’s largely illegal now, and went to Foyle’s books every single day. And miscellaneously ran into a friend (Imogen) in another friend’s (Adrian’s) club, which makes me feel like yes, I do have an actual community here.

I also stopped off at Fortnum and Mason and got Alastair a stash of Turkish delight, which he enjoys in a way that seems frankly sinister to me.

Other than that, I’ve primarily been doing Plough things and procrastinating on writing two pieces for The Critic and so on. Heads up: our next issues are going to be on a) Nature and b) Technology: if you have any ideas for pieces or writers, or if you’d like to pitch me, let me know at sblack.pq@gmail.com. I’m also in the market for podcast guests for our Repair issue.

The main other thing I have been doing is becoming massively obsessed with chicken stock: how to make it, what to do with it, etc. It is a true passion. I welcome all suggestions on that front also.

It has been wonderful to be back together, and to be back in the UK to see Alastair’s parents and our friends here. It’s also been a bit weird for me to feel so keenly aware of being Jewish in a place where that’s a good bit more of a rarity than New York City, in these Troubled Days. I’ve been attempting to find some kind of Jewish Christian or Jewish/Christian or something community here in the UK, which contains only 1/3 the number of Jews who live in the five boroughs of New York City alone. 0.5% of the population vs. 9%. This just blows my mind and makes me feel like some sort of Jackalope, or another rare cryptid.

Meanwhile: blessings on you all and I will leave you with pictures of soup and chicken and challah and other good things.

Alastair: As I write this, we are on a TransPennine Express service from Manchester to Durham. We will be spending the next week up north, enjoying the Lumiere Festival in Durham, catching up with friends, and exploring more of the northeast; I will be speaking at an event in York next weekend and then we will spend a day in London.

Since we last posted here, we have been settling back into life in Stoke-on-Trent together. Susannah returned on the 2nd and, since then, we have gradually returned to our more familiar routine. Stoke-on-Trent has been pleasantly autumnal and the mild weather has allowed us to enjoy a few walks.

Trentham Gardens, our local Capability Brown designed park, had some spectacular autumn colours on display, in addition to the wildlife. Since it is only a few minutes away from our house, we visit throughout the year, so the seasonal changes are so much more noticeable for us.

Susannah returned with a bad case of bronchitis, which I fortunately escaped, but it meant that we were limited in the socializing that we could do for the first week or so, especially with my parents. My father, who had been impatiently waiting to catch up with his daughter-in-law, was delighted when we were finally able to catch up properly over a coffee.

Much of our mail goes to my parents’ house, so we have near daily occasion to visit them. Of late, missing some of her library in the US, Susannah has purchased numerous books online. She was away for a few days in London and returned to a vertiginous pile of parcels on her desk. A season of pedestrian and rooted life in Stoke has its benefits. We’ve been enjoying Staffordshire oatcakes for breakfast and I also introduced Susannah to pikelets for the first time.

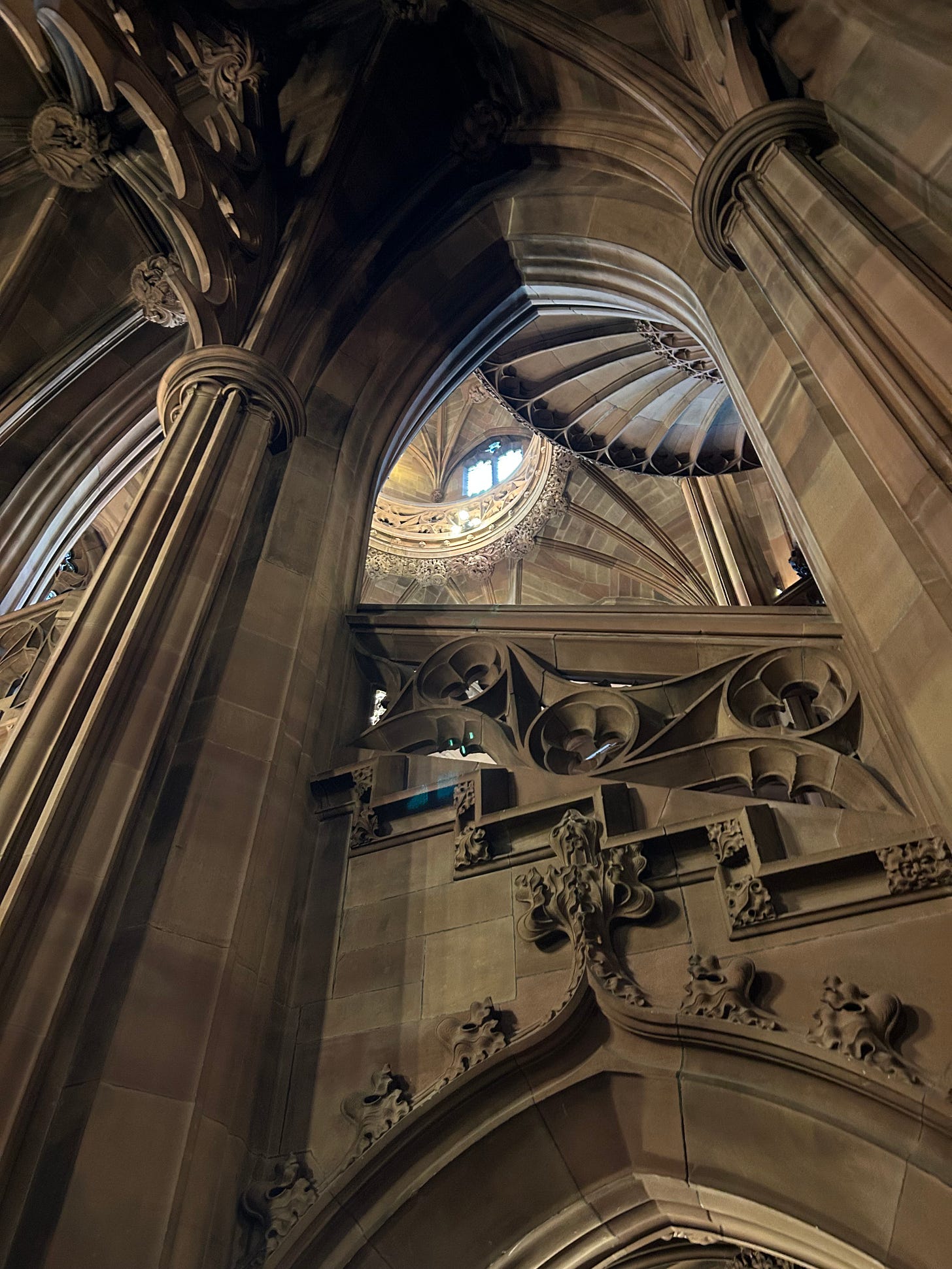

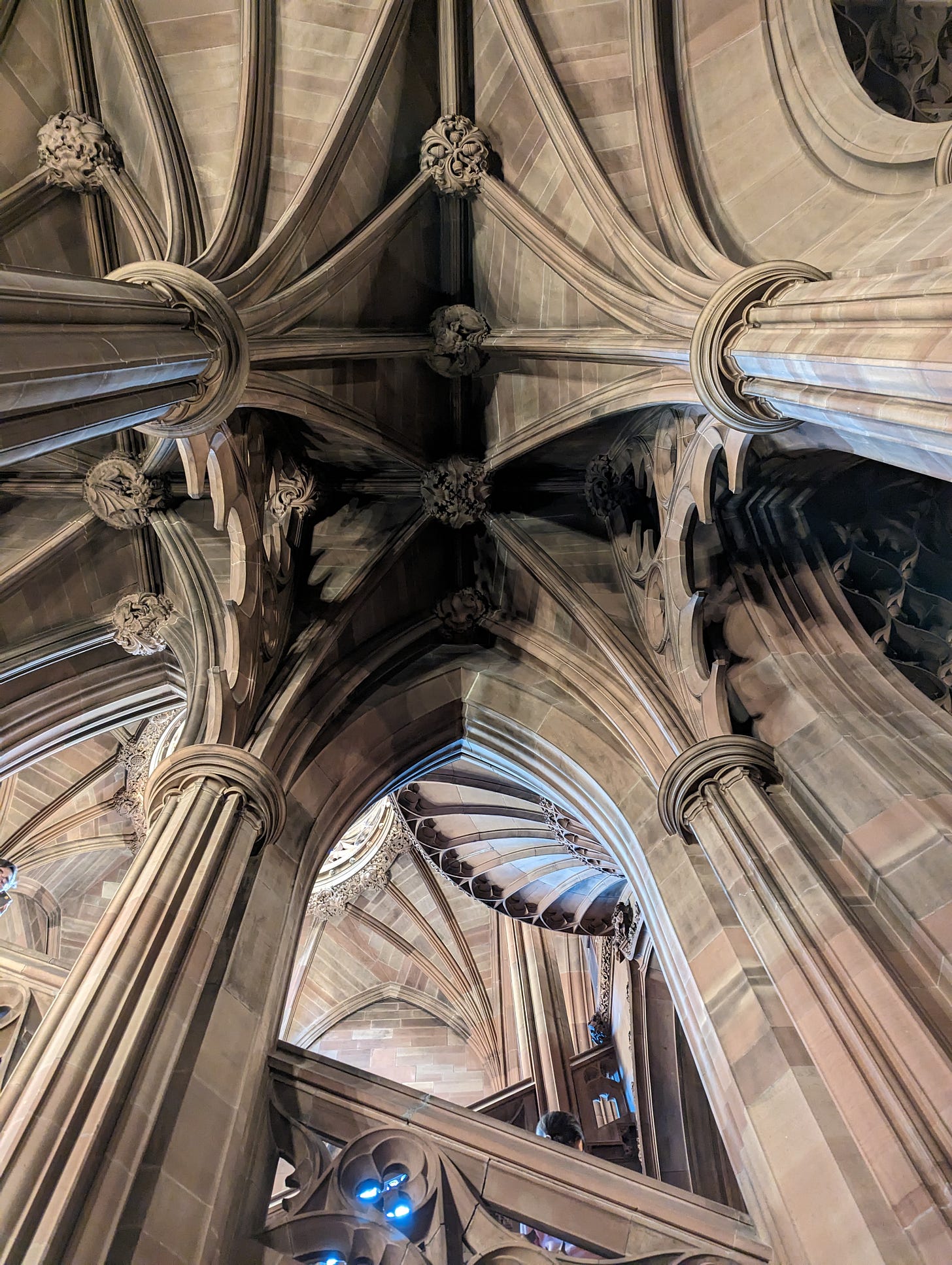

Passing through Manchester on the way to Durham today, we had about an hour to spare before our connection, so we visited the Rylands Library. The Rylands Library is a glorious neo-Gothic building, with one of the most important collections in the UK.

As I finish writing this, we have arrived in Durham, and I have been reunited with one of my favourite creatures. I’ve missed him a lot!

Susannah: His name is Penny. He stole a sausage from a plate I had set aside for Alastair, earlier tonight. He exhibited no remorse.

The sausage thief

On ‘Empathy’

Alastair: Over the past several years, in part through the influence of Edwin Friedman’s book A Failure of Nerve: Leadership in the Age of the Quick Fix, some conservative Christian writers have written a lot about the dangers of an unchecked ‘empathy’. Their arguments have excited considerable controversy, chiefly on account of the way they routinely speak of ‘empathy’ in ways that carry negative connotations and the ways that their analyses are employed in culture war and other related antagonisms.

I have long recommended the work of Friedman, which has influenced my own thought and practice in several respects. While Friedman has insightful things to say about empathy, the heart of his work for me has always been his treatment of self-definition. Where his analysis of the dysfunctional ways that empathy can operate within societies and communities is detached from this, his critique of dysfunctional empathy can easily come to function in a reactive manner. The strength of Friedman’s work, in my estimation, is his emphasis upon self-mastery over reactive antagonism: the transposition of his empathy critique into a more polemical form can easily undermine this fundamental posture: ‘You/they are weaponizing empathy!’ can take the place of the self-discipline of practising compassion for people and being sympathetically attentive to the ways that others see and experience the world, while resisting any tyranny of others’ emotional demands upon us.

Talking fruitfully about the limitations of ‘empathy’ is challenging, as the term carries very different, yet typically strong, connotations and associations for different people. It can be highly theoretically freighted in various systems of thought, with contrasting stipulated meaning. This would be challenging enough to negotiate. However, the situation is made more complex by virtue of the fact that the term has radically contrasting valence within different systems and frameworks (e.g. Brené Brown, Edwin Friedman, Paul Bloom).

In order to navigate this, some of the critics of empathy have qualified their terminology in various ways, speaking of, for instance, ‘untethered empathy’. However, although such terminology may be meaningful in the stipulated sense the critics employ, it isn’t always so effective at communicating with those accustomed to a general and non-theorized use of the term ‘empathy’ and perhaps even less so with those operating within alternative theoretical frameworks. In no small measure in consequence of the equivocal use of key terminology, ‘empathy’ debates tend to be heated and fruitless. They are incendiary and divisive on social media, yet seldom result in substantive and illuminating engagement.

Where debates increasingly stumble over terminology, it might be worth considering whether we would be better off removing certain terms from our active vocabulary for a while, at least in more general contexts. Temporarily dropping terms from general circulation prioritizes the task of effective communication over polemics. ‘Tabooing’ charged terms for a time also encourages us to consider different ways of saying the same thing. By disallowing theoretically freighted and emotionally charged terms in our vocabulary, it can encourage clearer and more careful thought, which isn’t allowing either dominating ideological frameworks or the emotive valence of vague terms to do our thinking for us. This keeps our imaginations limber, challenging us to think about how the world appears to other people and how to communicate beyond our preferred theoretical and ideological frameworks. It also helps us to consider the logic of systems and ideas from within and without, reducing the likelihood that our imaginations will be constricted by them.

While it may not be time to taboo the term ‘empathy’, I would encourage those engaged in these debates to be more circumspect in their choice of terminology and to think of ways to reduce the conceptual freight that such a divisive term is bearing.

If you read the material some have written on ‘untethered empathy’ calmly and carefully, there are important points being made. Our feelings of empathy are most definitely not a north star for moral action. Indeed, they can often distort our vision. Rather than putting empathy in the driving seat, we ought to be people of responsible moral judgment, not simply swayed by the partiality of feeling, nor sucked without resistance into the gravity well of other people’s demanding emotions.

It should be recognized that many of the people who are most gung-ho about the positive character of empathy have ways of talking about some of these issues. For instance, they will emphasize the necessity of ‘boundaries’. This said, while their treatment of empathy may be one that aspires to extensive application, due to the nature of the empathy they are championing, it tends to make moral judgment very difficult, so strict boundaries can be emphasized when it comes to evil or ‘toxic’ people.

As such empathy tends to dampen moral judgment, there can be a trade-off between the two. Classes of persons that are more likely to excite empathy as perceived victims or underdogs, for instance, are much more likely practically to be exempted from clear moral judgments. Due to the interference between empathy and moral judgment and the trade-offs between them, where moral judgments are deemed necessary, empathy can be almost completely removed, persons or groups can be demonized, and a sort of callousness developed towards them.

Empathy, critics like Paul Bloom have argued, is a focusing and excluding emotion. Our empathy towards one group easily makes us very callous towards others. It also lacks perspective: the suffering of one loved party can eclipse all else.

This dynamic is very evident during wartime. It is a reason why, for instance, posters of Israeli hostages have proven threatening to many supporters of the cause of Palestinians. As a focusing emotion, many instinctively register appeals to empathy as a zero-sum game: any empathy with Israelis weakens the Palestinian cause.

This sense isn’t entirely irrational. The callousness with which so much war is waged can counterintuitively often require elevated levels of empathy. When one group’s suffering becomes all-consuming for you, it can be very easy to wish extreme suffering upon their adversaries. When empathy dominates your moral and emotional repertoire in responding to the suffering of others, things can go very badly wrong in such situations: empathy has its under-considered shadow side.

Bloom, for instance, highlights the differences between ‘empathy’ and what he terms ‘compassion’. A key difference is that ‘compassion’ (as Bloom defines it) feels and takes concern for others, while maintaining emotional and other boundaries. That compassion can do this without so identifying with or being sucked into the narrow and exclusionary frame of another’s suffering expands its possibilities.

It greatly weakens the zero-sum dynamic of ‘empathy’ (again, as Bloom defines it), as compassion for one party need not prevent one feeling compassion for their adversaries. It also makes it entirely possible to feel compassion for people, while making firm negative moral judgments concerning their behaviour.

All this is possible while maintaining an essentially positive assessment of empathy in its own place too. While ‘boundaries’ can be very important in broader relations and in relation to dysfunctional people nearer to us, lowered or more porous boundaries are very good and important things in their proper place. Such focusing empathy really is a key part of what binds us to children, to family, and to those closest to us. It is a facet of the specific forms of love that belong to and can be exclusive to such relationships. Without such empathy, the world would be a much colder place.

It is also worth recognizing such empathy is commonly found in its most pronounced and archetypal forms in women. This, for instance, is a key dimension of the love a mother has for her infant. This should be borne in mind when considering the consequences of giving empathy a negative valence.

We clearly recognize ways empathy can hamper a mother's ability clearly to perceive the character of her child—‘he could do no wrong in her eyes’—or to judge even-handedly between her child and another child who is in conflict with him. Empathy is good, but needs to be tempered and can compromise our capacity in certain important tasks.

There are undoubtedly ways in which a sort of maternal empathy has been made a guiding and moralized emotion in wider realms of human society and relationships, in ways that prove very damaging, setting up perverse structures of partiality, and dulling capacity for moral judgment. Empathy for ‘victim’ and marginal classes, for instance, has often had the effect of dulling moral clarity and our social capacity for impartial justice and judgment.

The critics of so-called ‘untethered empathy’ have address some of the ways empathy can go wrong well. However, there may be a much weaker account of the good of healthy empathy in their work (perhaps on occasions this has been related to a characteristic failure adequately to valorize traits perceived to be more ‘feminine’ in character). While their work can be a needed corrective for some, it may be more effective at identifying dysfunctions than in encouraging healthy function. It is more medicine than solid food. And, where such ‘medicine’ is mostly being consumed by people other than those who most need it, the effects may even prove damaging, hardening some people who might be more in need of increasingly their capacity for compassion.

The focus tends to be on dangers of empathy ‘untethered’ from reality and truth and resistance to moral judgment. The analysis and practice too easily stalls in a negative moment, focusing upon resistance to ‘empathy’, rather than cultivating and practising healthy compassion. Where a correspondingly robust positive movement in the direction of compassion is lacking, empathy critiques can remain locked in zero-sum game trade-offs between empathy and judgment, discouraging loving concern for any for whom such feeling might threaten our moral judgments. With a weaker understanding and analysis of the nature of empathy, and lacking a catholicity of compassion, such positions are too easily reactively drawn into the gravity wells of alternative empathetic attachments, commonly those of white middle American Christian males.

Among other things, as Christians we have a duty to practice moral and loving emotional concern for oppressors, wrongdoers, and our enemies. This is especially important to remember as the empathy critique so often gets employed to serve culture war antagonism. The alternative to being tyrannized by other people’s feelings and having our moral judgments disabled by them need not be that of cutting off loving feeling and concern for them (or acting as if moral judgment alone is sufficient to constitute such concern and feeling).

A further benefit of ‘tabooing’ or reducing the conceptual freight of terms like ‘empathy’ in our vocabulary may be that of greater openness to the insights of other frameworks, which use the same term in different ways in connections. For instance, many have used the language of ‘empathy’ to speak of the capacity of imaginatively and sympathetically entering into other people’s ways of perceiving and experiencing the world. Such a capacity will make us considerably more effective at bridging the divides between our conceptual and perceptual worlds and those of others. ‘Empathy’, so defined, doesn’t really fall under the criticisms typically raised against ‘empathy’, but honing our capacity for it could really help in our ‘empathy’ debates.

Questions for Attentive Bible Reading

In the course of my work, I often lead students and laypeople in the study of biblical passages. I chiefly focus on priming them to pay attention to the text more broadly. I recommend they start by putting questions to one side and practice listening to the text.

After some more general initial attention to a passage and having elicited insights from the group on this, I will typically guide the conversation towards more focused attention. There are dozens of questions that I will use to encourage such focused attention. Here are some examples.

First, some questions for narrative texts.

1. Are there any details, terms, or expressions that surprise you or jump out at you in this passage?

2. Are there any aspects of the passage that remind you of another passage or passages? Where have you heard various details before?

3. Are there discernible literary structures? How would you identify the boundaries of the passage and how would you divide it up?

4. If you did not know what happened next, what would you expect? Why?

5. Choose three characters in the narrative: how do you think they were perceiving

events?

6. By what means does the text characterize key figures within its narrative?

7. If you had told this story yourself, how might it differ from the biblical account? What might explain these differences?

8. Are there any surprising omissions or absences in the story?

9. How does this narrative provide background for, anticipate, or even foreshadow later narratives?

10. To what larger narrative movements does this narrative belong? How does it serve their ends?

11. Are there other biblical narratives or texts that cite or allude to this passage?

12. If this narrative were removed, what would be lost to the book it is in and to the biblical narrative?

Second, some questions for epistolatory texts.

1. How, in your own words, would you summarize the argument of this chapter?

2. How does this passage follow from or relate to the argument of the letter as a whole, or from that of the preceding passage or passages?

3. How would you define the boundaries of this passage? Why? What is the structure of this passage? What literary features help us to divide and order it?

4. Imagine you held the position that Paul (or whichever letter-writer it is) is arguing against here: how would you argue for it? Why would it be persuasive to you?

5. Are there key metaphors underlying the argument of this passage?

6. Are there key terms or families of terms in the vocabulary of this passage?

7. What rhetorical strategies is the writer using? What is he doing in specific statements within the passage (rebuking, exhorting, encouraging, etc., etc.)?

8. How are the hearers of the epistle implicated within this text?

9. What can we discern about the implied audience from this passage?

10. What literary structures/devices do you recognize in this passage?

11. What scriptural allusions do you recognize in this passage?

12. Why, of all the arguments he could have made, does Paul use the arguments that he does here? If we had never read this particular passage, is this the argument that we would most likely make if we faced the same challenges? If not, why not?

This is by no means a comprehensive list of such questions, nor have I provided questions for poetic texts, for prophetic or apocalyptic works, or for wisdom literature. However, they are a good place to start and offer examples that might inspire you to consider further questions that guide and excite fruitful attention.

Are there any questions that you have found especially helpful in your own studies?

Recent Work

Alastair

❧ Our latest Mere Fidelity episodes were on the subject of Guarding Our Souls in Wartime and The Perplexing Book of Zechariah.

❧ The Theopolis Podcast’s series on Deuteronomy continues with episodes on Deuteronomy 19: Property Boundaries and Witnesses and Deuteronomy 20: Wars and Just Wars.

❧ My series on the book of Revelation with the God’s Story Podcast continues with an episode on the 144,000 and the harvest in Revelation 14.

❧ I was invited onto the Who Needs Western Civ? podcast for a conversation about the Christ-haunted character of Western culture, which you can listen to here.

Upcoming Events

❧ Alastair will be speaking at the International Presbyterian Church presbytery meeting in York on the 25th November.

❧ The third UK Davenant Convivium will be on the 24th January, with Oliver O’Donovan as the keynote speaker.

❧ My Hilary Term Davenant Hall course, starting in early January, will be on ‘The Bible and Politics’:

The words and teachings of the Bible are frequently deployed and appealed to in our political discourses. Yet such engagement with the Bible is typically superficial and merely rhetorical; while the Bible affords shallow prooftexts and resonant turns of phrase, it is seldom serving as a deep and guiding source of wisdom in our political thinking. In recent decades, after a long period of neglect, the importance of the Bible’s influence in historic political reflection has received growing attention. In addition to considering such retrievals of the Bible’s significance as a political text for historic thinkers, this course will seek to discover more of the Bible’s enduring insight and generative potential for political reflection. We will investigate some of the variegated ways that the Bible encourages, serves, and directs our political reflection and consider how we can engage with its voice most responsibly and profitably.

You can register for the course here.

❧ Most of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Susannah and Alastair

I always enjoy your slow and deliberate takes. It seems to me that the injunction to not be partial in judgment either to rich or poor is itself a command to the discipline of empathy, because in the very act of considering someone's social state, we have to exercise our imaginations in a discplined way to ferret out the biases we might be prone to in our judgment.

I've also always been fascinated with the wisdom Nathan employed to convict David. The little tale was basically an atom bomb wrapped up in an innocuous-seeming package of--empathy. David's sense of righteous indignation wasn't in itself hypocrisy, it was a just judgment, and it depended for its power upon David's having been a shepherd boy. Quite a weaponization of empathy on Nathan's part, but in an incredibly helpful direction!