№ 36: The Tree and the Throne

Embiggening societies, metacontexts, breaking the Window, a family visit, and other adventures

Dear friends,

Susannah [20th August]: The following is nearly all Alastair - our next post will be mostly my travels over the past month and a bit; it honestly would have been too long (even for us!) to include all my pics as well in this. (Also, as Alastair notes repeatedly below, I have been procrastinating.)

Alastair [27th July]: I am currently sitting in Birmingham Airport, having spent the last fortnight at the Theopolis Ministry Conference, Fellows Program, and the inaugural Te Deum Program. As usual, it has been an intense and exhausting time, yet immensely enjoyable and encouraging. I fly to Atlanta this afternoon, then back to Manchester this evening. I will arrive back in Stoke early tomorrow (Sunday) morning, at which point I will badly need to collapse.

We last posted on the afternoon of the Fourth of July. That evening we joined two groups of friends for picnics in Riverside Park. Susannah’s godson and his family—including her adorable infant goddaughter—were there, which was an especial highlight.

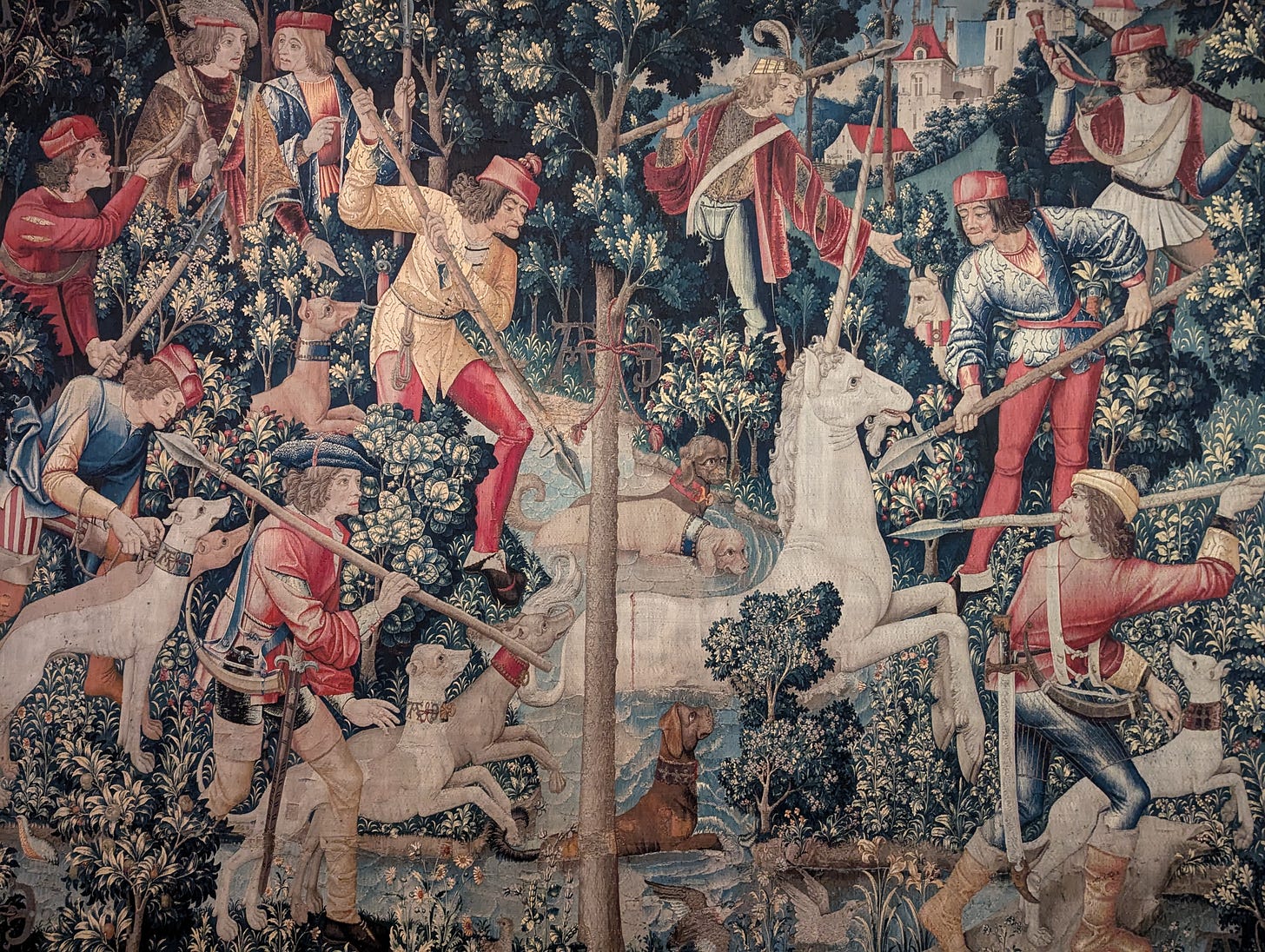

Some friends of ours were up from Philadelphia were up in New York over the weekend. As it had been some time since I had last done so, we spent Saturday afternoon in the Met Cloisters, a museum of chiefly European medieval art and architecture. The Met Cloisters is styled after a medieval monastery and is ordered around four cloisters, originally brought over from France in the 1910s.

Although the Met Cloisters is considerably smaller than the main Met building, I have always preferred it on account of its delightful ambience and its marriage of the art to its space. Wandering through and around the cloisters, one can occasionally forget that one is in a museum: the building invites you into the world of the art, in ways that the Met Fifth Avenue cannot. As so much of the art is Christian religious art, the fittingness of the space to the art reduces the sense one can have in many museums of such art having been utterly stripped of the living world within which it once had its meaning.

During our visit to the Met Cloisters, I took the occasion to become a member of the Met Museum, which, as the main Met Fifth Avenue is a relatively short walk from our house, was greatly overdue.

Before ending the day with tapas and ice cream, we visited Cleopatra’s Needle and meandered through Central Park. Wandering through Central Park on a pleasant summer’s evening, with golden sunlight coming through the trees, picnickers lounging on the grass, people chatting on benches, joggers and dog walkers passing by, children playing on the grass, and squirrels scampering up trees, I am reminded of how much I love New York and its fulness of life.

Our friends joined us at church on Sunday morning. We parted ways after eating some ice cream together.

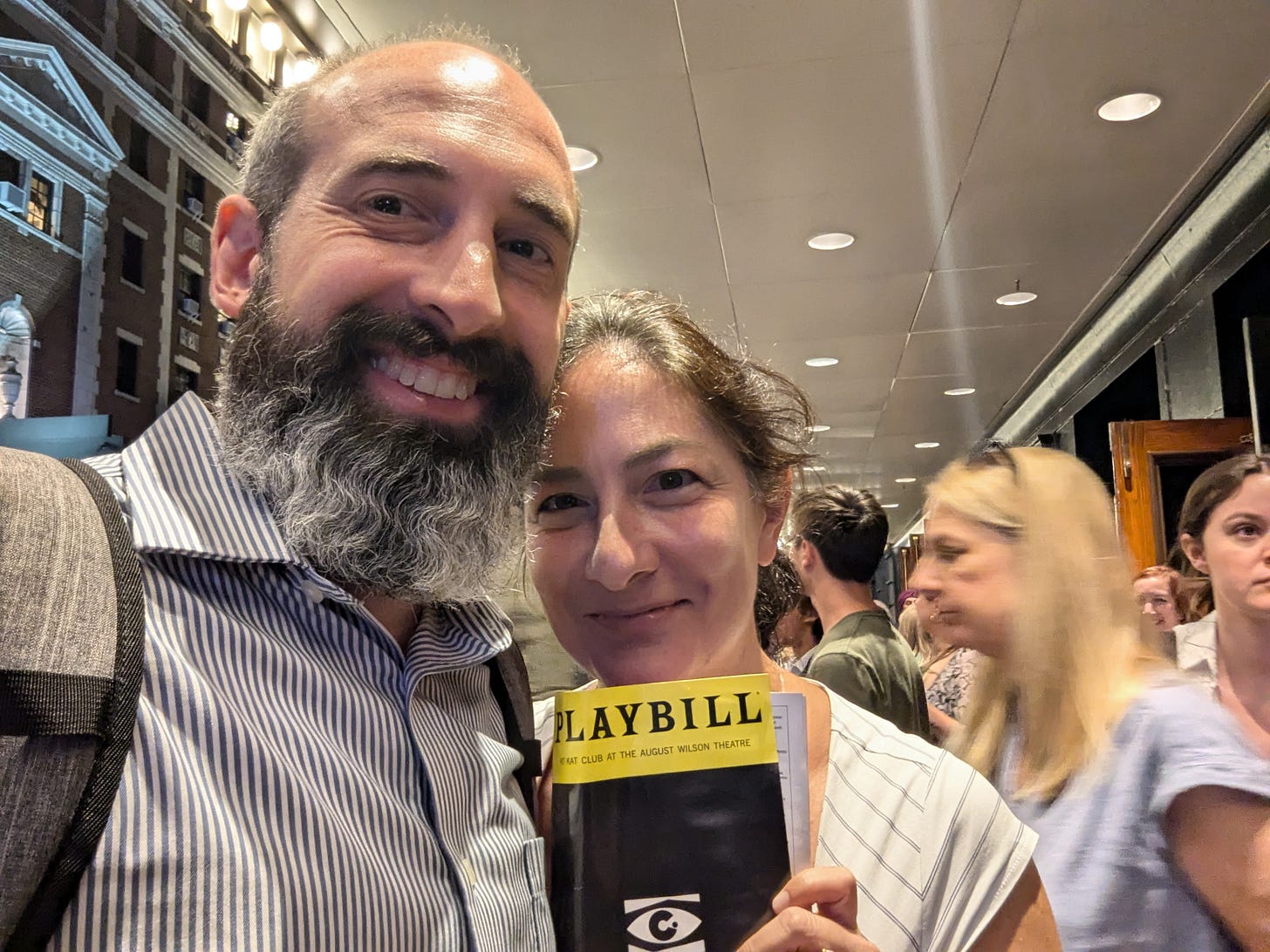

As I was leaving for Birmingham on the Saturday, I was going to miss Susannah’s birthday, so we decided to celebrate it a week early. It was also going to be our last week together in New York until late November, so Susannah was eager to make the most of opportunities afforded by the city. I bought tickets to Cabaret for the Monday evening. I had never seen the musical before—I have hardly seen any musicals—and Susannah wanted to see its recent Broadway revival.

The August Wilson Theatre had been converted into the Kit Kat Club for the production. We entered through a back entrance, were handed a drink and directed into the bar area, where dancers evoked the world of a Weimar-era Berlin club. After a half hour in the bar, we went up to our mezzanine seats. The theatre was in the round. Eddie Redmayne’s part, his interpretation of the emcee’s role having been the cause of some controversy among musical afficionados, was played by his understudy the evening that we went. As I had not seen any other productions of the musical, I was not in a position to assess its relative merits. I enjoyed the performance, although far preferred Hadestown.

Considering how busy and productive our final week was, we did a surprising number of other things. On the Wednesday evening we went to a talk by Susannah’s stepmother about her new book, Strong Passions: A Scandalous Divorce in Old New York, at the Salmagundi Club. The book has received superb reviews in the New York Times and there was standing room only for her presentation. We met up with Susannah’s cousin at the event and hung out with him afterwards. The next morning we had breakfast with Susannah’s dad and stepmother.

Before leaving I also finished much of the rest of a sweater that I had been knitting. I will need to ‘steek’ it when I return, a daunting process that involves cutting through the entire work, upon my return in November.

We also took advantage of my new Met Museum membership and had a brief visit to the Met Fifth Avenue on our final afternoon, spending most of our time in the Egyptian section. The vertiginous depth of Egyptian history is always awe-inspiring to me.

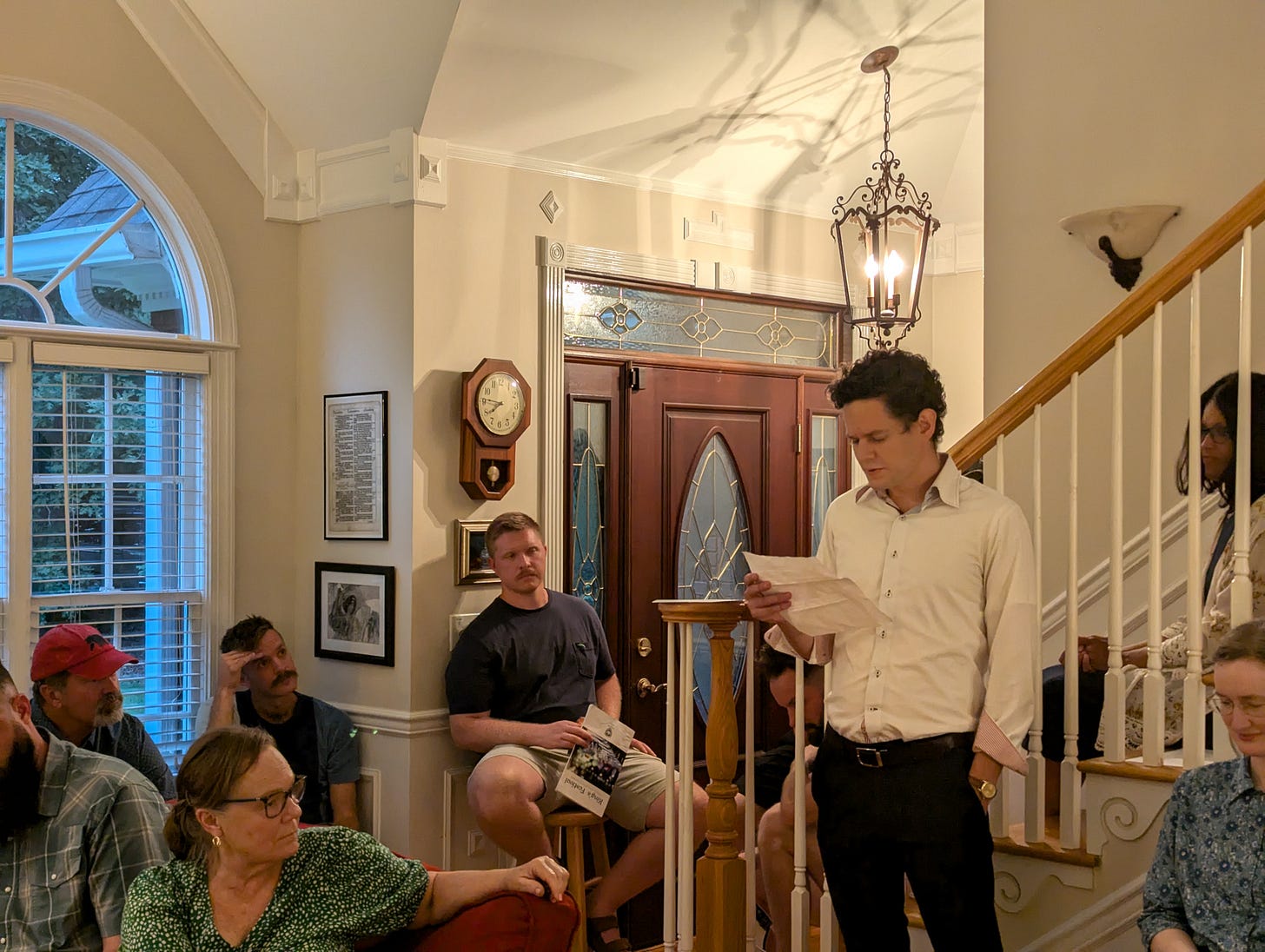

I arrived in Birmingham on the Saturday. Monday and Tuesday were the Theopolis Ministry Conference, at which I was one of the keynote speakers. The Ministry Conference gave me many opportunities to reconnect with old friends and to make new ones. On Monday evening, we had a meeting of Theopolis Fellows Program alumni. Reconnecting with former students is always a highlight of the Ministry Conference. On the Tuesday we had a partners breakfast in the morning and a Theopolis feast in the evening.

Wednesday evening was the introductory event of the Fellows Program and, after a couple of online meetings in the morning, I had the whole afternoon free. A friend invited me to visit the Birmingham Zoo with him. The last time I had visited a zoo was five years previously, so I was not about to pass up the opportunity.

We passed a very enjoyable afternoon at the zoo, seeing almost all the animals. The primates are almost always my favourite creatures to see, but there were several other highlights, most notably the elephants.

I have written about the summer term of the Theopolis Fellows Program before. It is the flagship program for Theopolis. Each program runs over a six-month period, with residential periods at the beginning and the end: a week and a half in July and a week in January. In the intervening time we have fortnightly online ‘Pesher groups’, within which the fellows, divided into three subgroups, present work that they have done on set passages, working through the full scope of the biblical canon.

Each day of the Fellows Program is jampacked with activity. From breakfast at 8am to returning back to our accommodation at around 9pm, the day is filled with food, conversation, worship, and classes. The very high ratio of faculty to fellows and the length of time devoted to food and informal conversation, especially in the evenings, allow us to get to know almost all the fellows very well over the course of the time. Worshipping together in three daily sung services of Matins, Sext, and Vespers has the effect of binding the group very strongly together.

This year had several exciting developments for Theopolis. In addition to the start of a new alumni group, it was the first term of a new program coordinated by the newly minted Dr John Ahern, the Te Deum Program. The Fellows and Te Deum Programs ran concurrently through this week and the students in each spent a lot of time socializing with each other. Neither being musical nor a musician, I have little to offer the Te Deum Program, but I did give them a talk on the importance of music as a conceptual metaphor for theology. Mark Brians, a young priest from Hawaii and a former Fellow himself, also joined the faculty for the Fellows Program and was an instant hit.

Over the course of the week smaller groups of us had various outings to bookstores, an antiques store, and elsewhere. On Tuesday some of us visited the Birmingham Museum of Art, which I had seen for the first time back in January—they do have a splendid collection of Wedgwood china! On Thursday evening, we all attended a piano recital by Joshua David Davis, which really was an unexpected treat.

The food and hospitality, coordinated by the amazing Laura Clawson, was once again the highlight of the time. This Wednesday we had a meal of toasts, modelled after a Georgian supra feast, led by our two tamadas, John Crawford and Mark Brians. We had dozens of toasts, thematically ordered after the days of creation and ending with the themes of death and resurrection. Several gave highly amusing toasts, some gave brief theological reflections (most notable among them John Ahern on Christ and the zodiac), and others spoke movingly about parents, spouses, and pastors, about loved ones they had lost, and about joys and debts of gratitude.

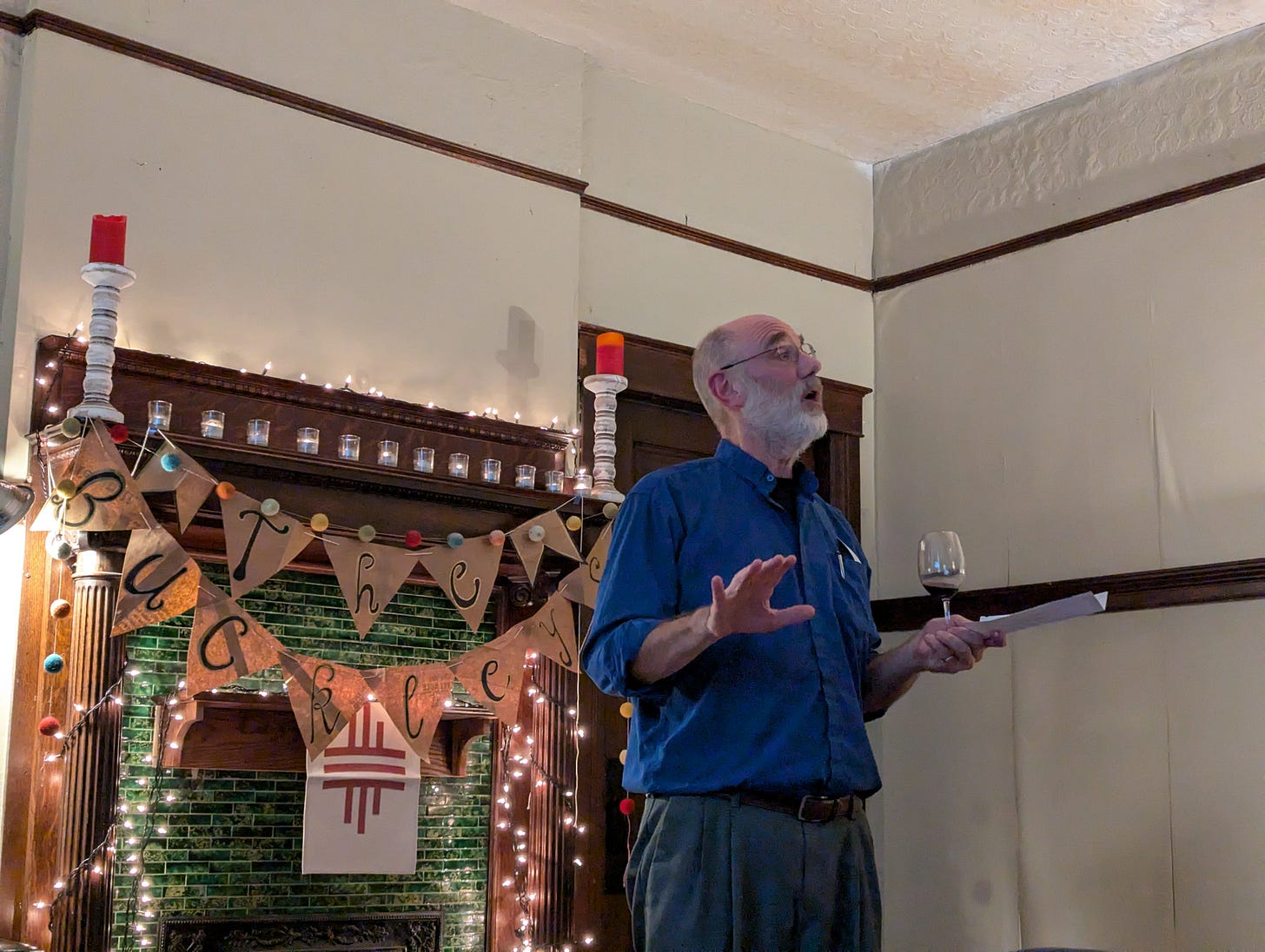

The celebratory atmosphere continued on the final night of the Fellows and Te Deum programs, when the annual Buckleys talent competition was held, presided over by the ‘Archbishop of Chanterbury’ himself, Paul Buckley. We were treated to a series of wonderful acts, including a faculty roast, several poems, several songs, among them a spirited rendition of “Moon Over Homewood” (the fellows’ house being beneath Birmingham’s Vulcan statue, famed for its shapely behind), group dancing, and a hilarious chanted introduction to the land of Australia from a proud New South Welshwoman.

I had planned to get a lot of work done while not teaching during the week. However, I ended up doing much less than expected, on account of many lengthy conversations, a couple of long video recording sessions, some podcasting sessions, and several meetings. The week was a joyous and productive one nonetheless. I was reminded, as I always am when I go to such programs, of the remarkable blessing that it is to be involved with Theopolis.

[Thursday, 1st August] I am now back in Stoke-on-Trent, where my brother Mark and his family are visiting from France. They are staying in our house with a friend of theirs and with my two nieces, the youngest of whom—a very energetic toddler—is constantly coming into my office to take me away from my work to do far more important things, like playing. It has been wonderful to see them again, and to spend time with my parents, whom I had not seen since the end of March.

We moved into our home—my parents’ old house—at the end of our last UK stint. Now that I have more space, I have also been taking boxes of books up to the attic where I work, sorting through them, and ordering my shelves.

Yesterday afternoon, Mark and I took my parents out to the canal near Kidsgrove. We had hoped to get to the entrance of the Harecastle Tunnel, but it wasn’t possible to get onto the canal towpath with my dad’s wheelchair, so after a short walk in the other direction we enjoyed drinks at a canalside pub.

[Monday, 19th August] Over a month ago, I suggested to Susannah that our next Substack post should be published on the 27th or 28th. I reminded her about it again the week beforehand. On several occasions since then, gentle reader, I have asked Susannah whether she would write her part for the Substack. ‘Absolutely! I’ll do it tomorrow’, was the typical response. Still nothing.

Anyway, this is my third news update.

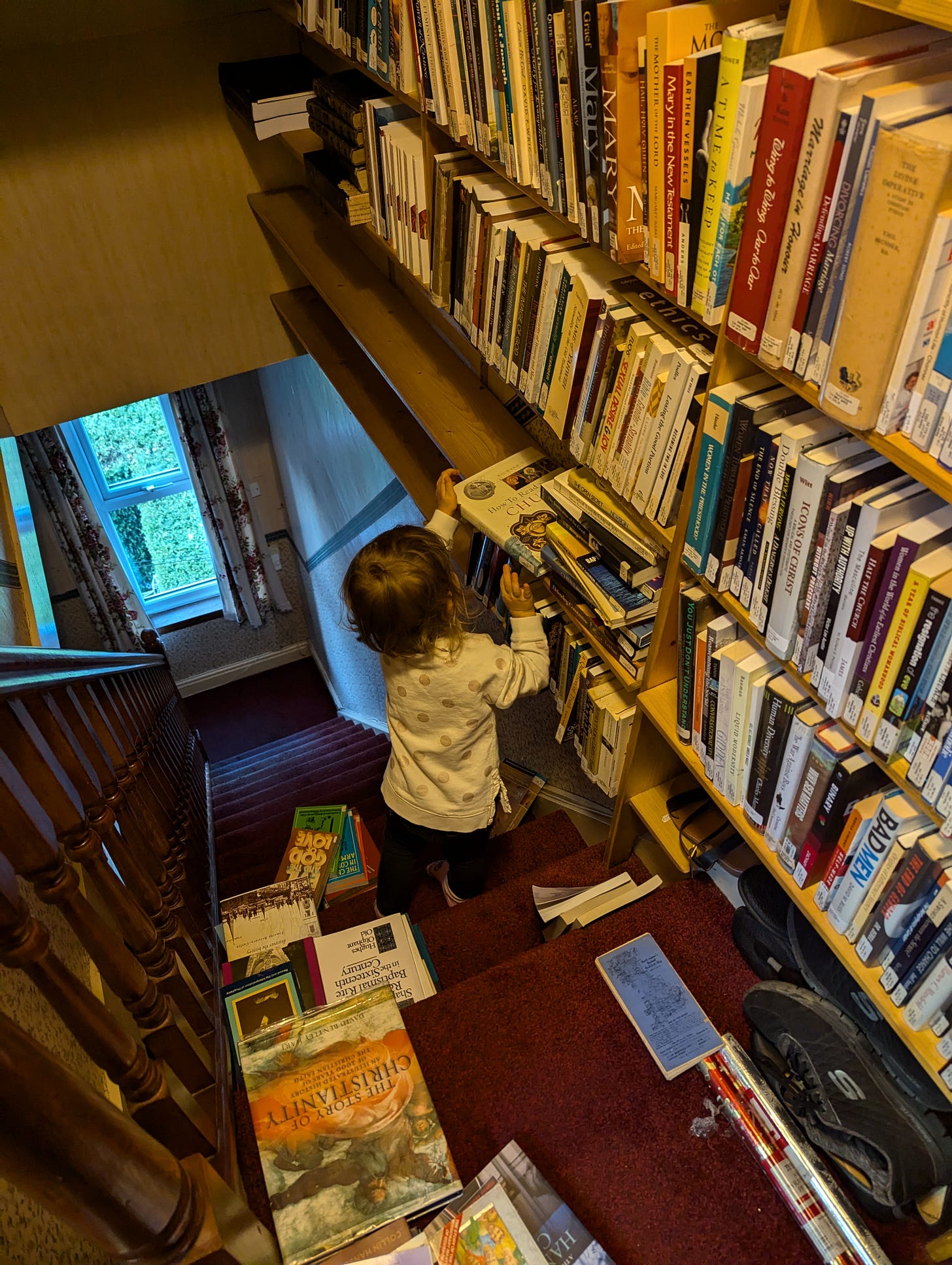

I finally finished sorting out my library, ordering well over fifty boxes of books onto shelves in proper order (my niece was very insistent on ‘helping’ me in the process!). It is now starting to feel as though we are properly moved in. The last task remaining is to get a bed.

We had a family celebration for my mother’s birthday on Friday at their home and another family celebration for which my brother Peter and his wife, Fernanda, joined us on the Saturday. Apart from Susannah, the entire family was there, which was quite special.

Susannah came back to the UK, but was down in London for the first few days. Several of us went down to spend a day with her on the following Thursday, walking around Westminster and then going to Greenwich to see the Royal Observatory.

For someone as excited by maritime-related places and history, Greenwich is catnip for Susannah. We had already visited both the National Maritime Museum and the Cutty Sark before, but this was our first time going into the Observatory.

The Observatory is the site of the Prime Meridian Line, zero degrees longitude, the division between the east and west hemispheres—hence, Greenwich Mean Time. The Observatory, designed in part by Sir Christopher Wren, is a charming building, built on the old foundations of Greenwich Castle. At the top is the grand Octagon Room.

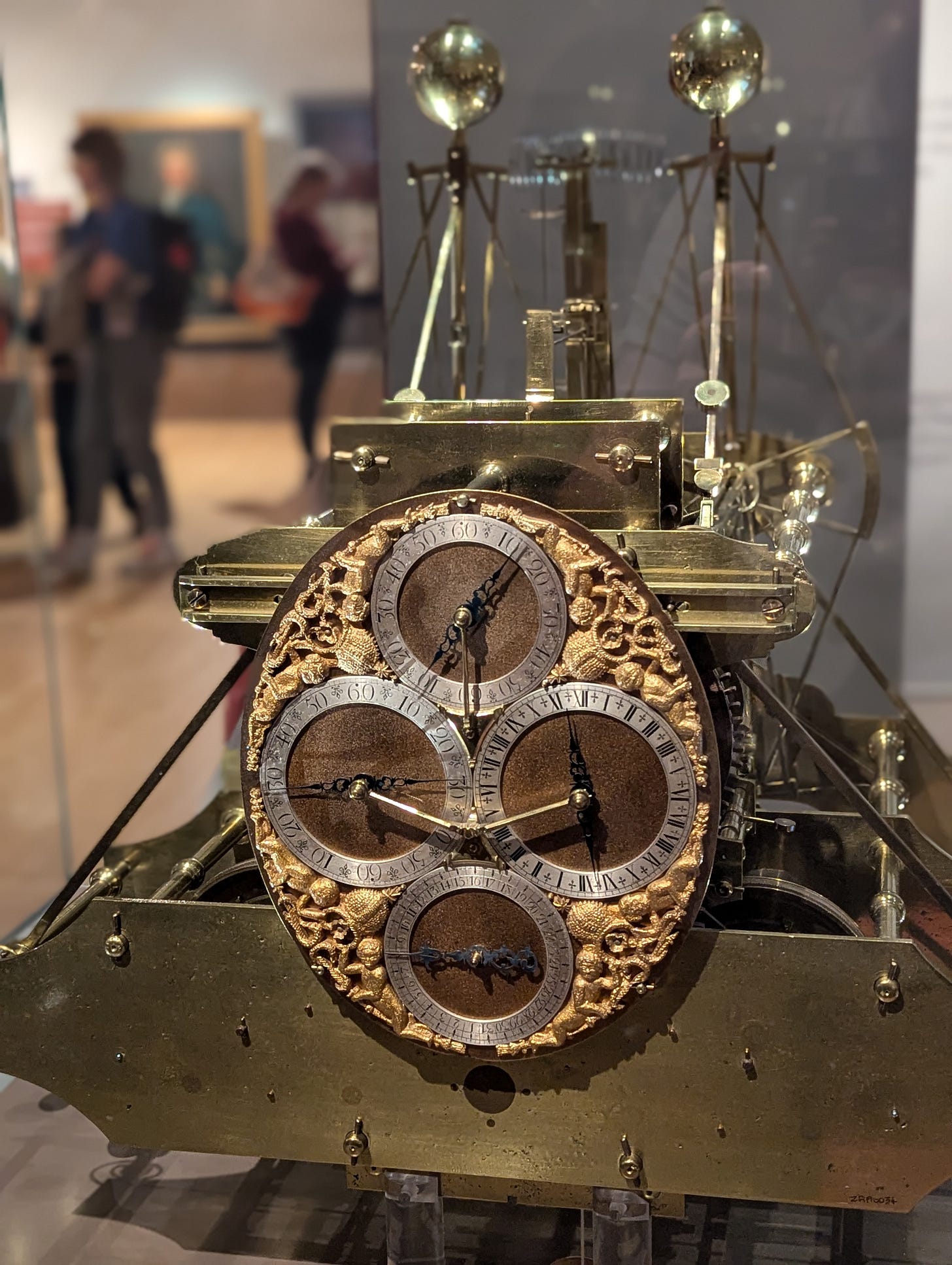

Elsewhere in the Observatory there are displays of clocks and other timepieces, including John Harrison’s famous marine chronometer, the H4, famous for cracking the problem of calculating longitude at sea.

Walking back from the Observatory, we encountered a small gathering of people at a nearby park, looking at a fox that was standing still and looking at them, later joined by a magpie. It was very bizarre, like some strange portent!

While the rest of our company returned to Stoke in the car, I had an open return on the train, so Susannah and I shared a meal, before walking past the Cutty Sark and then across the Thames in the Greenwich Foot Tunnel, which I had never used before.

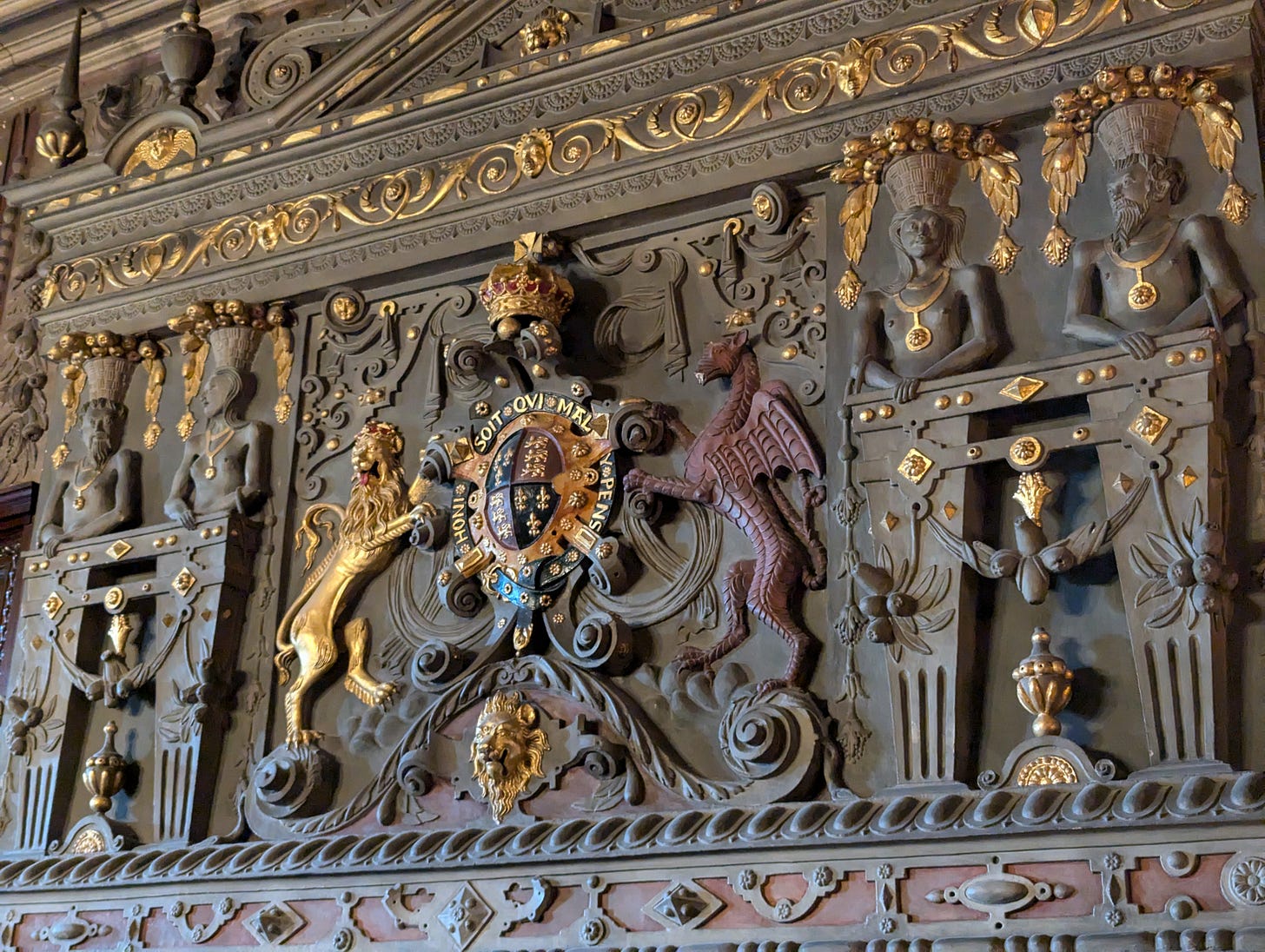

My brother Mark and his family had been unable to join us in London, so I spent much of the next day with them visiting Lyme Park, which I had previously visited for our first wedding anniversary.

Visiting Lyme with an energetic three-year-old in tow was a rather different experience, albeit a great deal of fun. They were offering period costumes to visitors, an opportunity which we could not pass up. My nieces were particularly delighted to dress up, although the youngest was quite distressed when she discovered that she had to return her dress at the end of our visit. Susannah was very disappointed that the one occasion I have ever dressed up in Regency costume she was not present to witness it! [Susannah: I AM EATING MY HEART OUT.]

After touring the house, my brother and I walked around the gardens, while the children played on the lawn and then ate in the café.

We drove back to my parents’ flat, where we dropped off the car and walked back along the canal.

Susannah finally arrived back in Stoke on the Sunday afternoon, when we celebrated my nephew’s birthday and settled back into life together in the house, from which we had been away since the end of March.

Over the past week, as the family are no longer staying in the house and Susannah and I are back together, we have been settling into more regular work and life routines again. We have picked a great many blackberries, along the canal and in several nearby parks. Susannah seems to have cracked a delicious blackberry pie recipe and by now we probably have foraged enough berries to keep us in such pies for the winter!

On Friday early afternoon we visited the Alsager Book Emporium, one of our favourite bookstores nearby. They have a well-stocked theology section and their books are always at bargain prices. Between us we picked up over seventy books, many of them Folio Society volumes in near mint condition, paying only a small fraction of what they would cost in a typical second-hand bookstore. In the evening, my parents came over and we talked and relaxed with them. It is a blessing to get to see them so often and to spend so much time with them.

On Saturday, we took a couple of hours out to visit Trentham Gardens, dropping by another park on the way back to do more blackberry picking!

It had been a while since we had last cycled, so on Sunday afternoon we took a brief cycle along the canal to visit my parents, taking a walk around a lake and nature reserve with them.

Susannah has an insane amount to share in her news update. However, as she has not yet been able to write it [Susannah: this is rather reproachful and pointed; don’t think I don’t notice], she will post it in our next Substack post, which will come at some point within the next two weeks.

Psalms 1 and 2 in Jeremiah 17 to 20

A few days ago, I was one of the examiners for a Theopolis fellow’s dissertation. The dissertation bristled with insight, exploring the relationship between the first two psalms. While the focus of the dissertation lay elsewhere, it prompted me to think about the presence of Psalms 1 and 2 in Jeremiah 17 to 20.

From Jeremiah 17 to 20, Psalms 1 and 2 are an intertext that is just beneath the surface. Psalm 1:1 and 2 liken the righteous man to a fruitful and well-watered tree:

Blessed is the man

who walks not in the counsel of the wicked,

nor stands in the way of sinners,

nor sits in the seat of scoffers....He is like a tree

planted by streams of water

that yields its fruit in its season,

and its leaf does not wither.

In all that he does, he prospers.

In Jeremiah 17:5-6 this comparison in Psalm 1 is inverted, with a curse upon the unrighteous man, likened to a shrub in a dry desert:

Thus says the Lord:

“Cursed is the man who trusts in man

and makes flesh his strength,

whose heart turns away from the Lord.

He is like a shrub in the desert,

and shall not see any good come.

He shall dwell in the parched places of the wilderness,

in an uninhabited salt land.

In the immediately succeeding verses—verses 7 and 8—Psalm 1’s similitude is repeated:

“Blessed is the man who trusts in the Lord,

whose trust is the Lord.

He is like a tree planted by water,

that sends out its roots by the stream,

and does not fear when heat comes,

for its leaves remain green,

and is not anxious in the year of drought,

for it does not cease to bear fruit.”

The allusions to Psalm 1 in Jeremiah 17 are universally recognized by commentators, but it seems to me that they do not represent the limit of the intertextual play of the opening psalms in this part of Jeremiah.

In verses 12-13, Jeremiah’s imagery moves to the Lord’s throne in Zion and defeat of his adversaries, as in Psalm 2, where the Lord sets his king on Zion, his holy hill.

A glorious throne set on high from the beginning

is the place of our sanctuary.

O Lord, the hope of Israel,

all who forsake you shall be put to shame;

those who turn away from you shall be written in the earth,

for they have forsaken the Lord, the fountain of living water.

Those who have turned away from the Lord are, in contrast to the righteous man planted by streams of water, those who forsake the ‘fountain of living water’.

In Psalm 2:9, the psalmist uses the imagery of breaking a piece of pottery for the overthrow of kingdoms by the Lord. In Jeremiah 18, the same imagery is given by the Lord as a symbol of national destruction to Judah through the prophet. Verses 1-10:

The word that came to Jeremiah from the Lord: “Arise, and go down to the potter’s house, and there I will let you hear my words.” So I went down to the potter’s house, and there he was working at his wheel. And the vessel he was making of clay was spoiled in the potter’s hand, and he reworked it into another vessel, as it seemed good to the potter to do.

Then the word of the Lord came to me: “O house of Israel, can I not do with you as this potter has done? declares the Lord. Behold, like the clay in the potter’s hand, so are you in my hand, O house of Israel. If at any time I declare concerning a nation or a kingdom, that I will pluck up and break down and destroy it, and if that nation, concerning which I have spoken, turns from its evil, I will relent of the disaster that I intended to do to it. And if at any time I declare concerning a nation or a kingdom that I will build and plant it, and if it does evil in my sight, not listening to my voice, then I will relent of the good that I had intended to do to it.

Jeremiah 18 returns to the imagery of Psalm 1 with its discussion of Judah’s loss of the flowing streams and abandonment of the highway of the Lord for the side roads of idolatry, leading to them being scattered as by the wind, as the chaff in Psalm 1. Verses 13-17:

“Therefore thus says the Lord:

Ask among the nations,

Who has heard the like of this?

The virgin Israel

has done a very horrible thing.

Does the snow of Lebanon leave

the crags of Sirion?

Do the mountain waters run dry,

the cold flowing streams?

But my people have forgotten me;

they make offerings to false gods;

they made them stumble in their ways,

in the ancient roads,

and to walk into side roads,

not the highway,

making their land a horror,

a thing to be hissed at forever.

Everyone who passes by it is horrified

and shakes his head.

Like the east wind I will scatter them

before the enemy.

I will show them my back, not my face,

in the day of their calamity.”

Returning to the themes of Psalm 2, the people gather together in conspiracy against the Lord’s anointed prophet, Jeremiah. They wish to strike him with their tongues, but, in the Lord’s wrath, they will be struck by the sword (a rod of iron), and their plots frustrated.

Then they said, “Come, let us make plots against Jeremiah, for the law shall not perish from the priest, nor counsel from the wise, nor the word from the prophet. Come, let us strike him with the tongue, and let us not pay attention to any of his words.”

Hear me, O Lord,

and listen to the voice of my adversaries.

Should good be repaid with evil?

Yet they have dug a pit for my life.

Remember how I stood before you

to speak good for them,

to turn away your wrath from them.

Therefore deliver up their children to famine;

give them over to the power of the sword;

let their wives become childless and widowed.

May their men meet death by pestilence,

their youths be struck down by the sword in battle. (18:18-21)

Jeremiah 19 returns to the theme of the broken pottery vessel, as Jeremiah performs the sign of the broken earthenware flask before the people. The people will be dashed in pieces and struck with the sword.

Thus says the Lord, “Go, buy a potter’s earthenware flask, and take some of the elders of the people and some of the elders of the priests, and go out to the Valley of the Son of Hinnom at the entry of the Potsherd Gate, and proclaim there the words that I tell you…

“Then you shall break the flask in the sight of the men who go with you, and shall say to them, ‘Thus says the Lord of hosts: So will I break this people and this city, as one breaks a potter’s vessel, so that it can never be mended. Men shall bury in Topheth because there will be no place else to bury. Thus will I do to this place, declares the Lord, and to its inhabitants, making this city like Topheth. The houses of Jerusalem and the houses of the kings of Judah—all the houses on whose roofs offerings have been offered to all the host of heaven, and drink offerings have been poured out to other gods—shall be defiled like the place of Topheth.’” (19:1-2, 10-13)

Jeremiah 20 recounts the abuse of Jeremiah and the promised destruction of Pashhur, the priest who beat him and put him in the stocks, of the internal struggle and agony of the prophet, and the awaited vindication and vengeance of the Lord. While Psalms 1 and 2 might not be the first passages to come to mind were we reading this chapter in isolation, given their intertextual importance in the preceding chapters, they offer an illuminating angle upon the complaint of the prophet. Jeremiah 20:7-10—

O Lord, you have deceived me,

and I was deceived;

you are stronger than I,

and you have prevailed.

I have become a laughingstock all the day;

everyone mocks me.

For whenever I speak, I cry out,

I shout, “Violence and destruction!”

For the word of the Lord has become for me

a reproach and derision all day long.

If I say, “I will not mention him,

or speak any more in his name,”

there is in my heart as it were a burning fire

shut up in my bones,

and I am weary with holding it in,

and I cannot.

For I hear many whispering.

Terror is on every side!

“Denounce him! Let us denounce him!”

say all my close friends,

watching for my fall.

“Perhaps he will be deceived;

then we can overcome him

and take our revenge on him.”

When you are alert to the Psalm 2 intertext, Jeremiah’s complaint in 20:7-10 evokes a text that answers it. Jeremiah is mocked and conspired against, but Psalm 2 is all about the Lord’s frustration of the plots of the nations and his ridicule of them.

Why do the nations rage

and the peoples plot in vain?

The kings of the earth set themselves,

and the rulers take counsel together,

against the Lord and against his Anointed, saying,

“Let us burst their bonds apart

and cast away their cords from us.”He who sits in the heavens laughs;

the Lord holds them in derision.

Then he will speak to them in his wrath,

and terrify them in his fury, saying,

“As for me, I have set my King

on Zion, my holy hill.”

The presence of the opening pair of psalms in the background of these passages is evidence of the importance of the connection between them. It also serves to accentuate and unite themes of the section.

Metacontextual Mischief

A common feature of our contemporary discourse is an overdependence upon metacontextual referents. A metacontext is a vague context of contexts, such as ‘the culture’, ‘Western society’, ‘the Internet’, ‘the current day’, or ‘our contemporary discourse’. Without denying the reality, importance, or illuminating character of metacontexts, it is sometimes necessary to recognize their limits as framing concepts and contexts.

I recently posted a reflection here, entitled ‘The Internet is the Negative World’. The concept of ‘negative world’—the claim that there has been a relatively recent shift to a society that is inhospitable to Christian faith—has been much discussed and widely deployed. While I think such concepts can be useful, I am wary of the ways such supposed metacontexts can start to blind us to our more concrete contexts.

A focus on our metacontexts is perhaps most characteristic of political conversations. Many diverse and formerly more defined contexts and realities can be dissolved into a vast imagined metacontext of warring ideological and political forces, e.g. ‘left’ versus ‘right’. Where this happens the perceived metacontext can frame the more immediate world, dulling our alertness to its particulars; everything is considered in terms of its relation to the great antagonisms of the metacontext.

While there is undoubtedly a place for thinking about these things, none of us are addressing ‘the culture’ or ‘the world’ as such. Our core audiences and contexts, even online, are generally quite defined. For most of us, these differ sharply from a ‘metacontext’ of ‘the culture’. We do not address ‘the culture’, ‘the left’, ‘the right’, ‘negative world’, ‘society’, etc. When we mentally direct our speech to metacontexts, we are in danger of speaking past the specific people who listen to us, considering them overmuch as manifestations of cultural forces.

An excessive focus on metacontexts sets us up for zero-sum games. As we cannot become all things to all people simultaneously, we must supposedly generally prefer some groups over others when we frame our speech by such metacontexts, giving them ‘preferential treatment’.

Such a focus on metacontexts is greatly encouraged by spending too much time in thin, weak, and decontextualizing contexts, of which much online social media is an example. We can become like the crazy street preacher, who speaks at a society that he imagines rather than an audience he knows.

Healthy speech requires clear contexts and audiences. There is no ‘word in season’ when we must speak to all seasons at once. Where our primary contexts have been so thinned out, decontextualize so much, yet are so totalizing, much of the repertoire and range of wise speakers is foreclosed.

Metacontexts such as ‘negative world’ can be used to set the terms for people’s speech. Since we are living in ‘negative world’, for instance, approaches to Christian speech in public that aim at ‘winsomeness’ are declared outdated. Or we must carefully posture ourselves within the antagonism between ‘the left’ and ‘the right’, ensuring that we never punch in the wrong direction. Since we supposedly inhabit a single metacontext, we must adopt a more uniform rhetorical approach. Rather than addressing variegated contexts and audiences in different ways, while maintaining our integrity, and focusing particularly on the audiences most proximate to us, we must favour audiences according to interpretations of the broader metacontext.

When people impose such a metacontextual frame upon discourse more generally, they can lose sight of the specific natures of people’s more immediate and bounded contexts, and the more specific ends that their rhetorical approaches can serve within them. For instance, so much ‘winsomeness’ I’ve seen in practice has been about highly contextualized speech which varies by person and setting. Christian truth is presented in its totality to unchurched people, yet in differentiated contexts and ways, and in a carefully considered order, seeking to overcome misunderstandings and all aiming at a faithful clarity and candour.

[Susannah’s translation of the above: There’s a whole phenomenon of rather pugnacious Christians who get irritated at other Christians who they consider to be not confrontational enough in their discussions of various aspects of Christianity with non-Christians. An excess of this “winsomeness” is often an accusation that the pugnacious lob at the less pugnacious. But so often, what’s happening is that people in one context (say, red state rural areas) are kind of listening in on the conversations of those who are not speaking to them (say, blue state urban areas.) People speak in contexts, and in order to be understood and to be courteous, this is a good and necessary thing.]

Speaking to poorly-defined audiences, such as those of decontextualized social media or imagined religious marketplaces, tempts us to turn to forms of speech that are diminished in their capacity for wisdom. They also encourage us to approach issues from a supposed god’s eye view, rather than from our very grounded position as moral agents with specific settings, vocations, relations, and duties. We must resist such tendencies, cultivating more grounded and contextualized speech, speaking to our specific and particular contexts in ways that call all to faithfulness.

Doing this well will require a lot more development of new contexts, so that we can address the full truth with focused clarity to people in ways designed that they in particular—not just a culture as such—are best positioned to hear it.

Embiggening the Smallest Man

In a recent post, ‘Matt Yglesias Considered As The Nietzschean Superman’, Scott Alexander has a fascinating discussion of the concepts of ‘slave morality’ and ‘master morality’. From the outset he is open about his limits as an interpreter of Nietzsche: ‘I’m an expert on Nietzsche (I’ve read some of his books), but not a world-leading expert (I didn’t understand them).’ His concern is less one of close and accurate interpretation of Nietzsche’s philosophy than to play with some ideas inspired by his reading of it, and to bring several other, mostly online, voices into conversation around them.

Pushing back against the identification of Nietzschean slave morality with morality simpliciter, Scott invites us to look at it from some different angles. Using Ozy Brennan, he proposes that we consider ‘master morality’ as favouring ‘embiggening’, while ‘slave morality’ favours ‘ensmallening’ (Ozy makes the humorous observation that the person most optimized for such a morality may be dead). Master morality challenges people and societies to strive towards glory, heightened agency, excellence, exceptionality, and pre-eminence, while slave morality favours those who are inoffensive, conformist, unassuming, unassertive, inobtrusive, indistinctive, undisruptive, and harmless.

Slave morality is a sort of herd morality and also an aversion to hierarchical judgments, a notion that Scott develops using ‘Edward Teach’ (aka The Last Psychiatrist, perhaps his more famous pseudonym). While master morality celebrates and encourages excellence, slave morality is threatened by the idea of excellence and seeks to oppose it in a variety of ways. The system is rigged, the standards are arbitrary, successful people are bad, trying to excel is weird or pretentious, high-achievers invariably hurt others and probably only advanced at others’ expense, successful people have impure motives, or selfishly pursued their ends without submitting to and cooperating with the judgments of society. There is a type of person who likes to see a high achiever come to ruin, be exposed, or be denounced, as their excellence and greater agency is an affront to their sense of cosmic justice.

Scott cites Jason Crawford, who maintains that something akin to a ‘vibe shift’ occurred in the mid-twentieth century. Whereas Western societies had formerly been animated by ‘embiggening’ visions, expressed in everything from bold technological advancement to colonialism to vast infrastructure projects, they shifted to an ‘ensmallening’ ethos of low risk, safety, environmental conservation, degrowth, high regulation, aversion to causing emotional harm, gnawing guilt, and cultural self-abnegation. This shift was probably occasioned in large part by the increasingly manifest evils that had resulted from and driven the old self-confident embiggening vision and the existential risks with which it had carelessly flirted—environmental disaster, nuclear annihilation, and vast injustices. Scott suggests that slave and master morality might function as ‘attractors’: ‘if you select too hard for part of one, you end up with the whole package.’

Scott considers different iterations and forms of slave and master morality, reflecting on Andrew Tate as modelling a form of despicable master morality and the Puritans and early twentieth century Progressives as interesting combinations of master and slave morality features. Likewise, he observes that Communist propaganda celebrated collective power, will, excellence, and boldness in ways that modern leftists do not. He discusses Ayn Rand, Matt Yglesias, and Richard Hanania as contrasting ways to deal with the dilemma of master and slave morality. For instance, Yglesias:

Slave morality hates power/excellence and refuses to justify it. Master morality says power/excellence is its own justification, and the rest of us have to justify ourselves to it. Liberalism says that sure, we can probably justify power/excellence, as long as it stays within reasonable bounds and doesn’t cause trouble.

Hanania is a curious case for Scott, as he holds to such a principled form of Nietzscheanism, which puts him directly at odds with much of the right. For instance, Hanania is pro-immigration, as he sees it benefiting talented people who want to come to the US, where greater achievement is possible for them—and the US through them.

[A]s Hanania has noticed, MAGA Republicans are slave moralists. They want the talented (high-skilled immigrants, economists, artists, intellectuals) to be permanently yoked to an underclass of obese conspiracy-theorist hillbillies. They’re raising tariffs to protect weak American companies from stronger foreign competitors, banning IVF and vat meat and any technology that makes them uncomfortable, and trying to retvrn to some kind of crunchy organic notion of life which probably doesn’t even have any skyscrapers. Even the right’s so-called Nietzschean vitalists are mostly LARPing steppe nomads instead of building rockets.

The master/slave morality contrast as Scott discusses it is arguably quite simplistic and far from a lossless compression of more complex ideas. However, he offers a potentially illuminating angle upon some contemporary issues, tensions, and dynamics.

The contrast between slave and master morality, on a more individual level, might be illustrated by something like the story of the TV series Breaking Bad, where Walter White, formerly a weak, compliant, timid, repressed, and resentful chemistry teacher ‘breaks bad’ after receiving a cancer diagnosis, becoming a powerful drug lord over the course of several seasons. Although he was regarded as moral by many in his former life, he was an abject and pitiable character in many respects. While his transition is a descent into extreme evil and moral corruption and the audience is left in no doubt as to his wickedness, Walt’s growth in power, influence, confidence, agency, and will might lead us to consider whether a moral Walt would necessarily have been a small and frustrated Walt or whether good people can—and should—also strive for an outstanding greatness that sets them apart from others (discussions of classical and Christian treatments of magnanimity are worth considering here).

While I think Scott’s discussion is generally helpful, as soon as you start to consider various movements in terms of his categories, their overly simplistic character becomes more evident. However, such consideration is stimulating, perhaps even due to the simplicity and eccentricity of the taxonomy. For instance, is wariness about AI to be understood as an expression of a sort of slave morality—risk-averse, resistant to destabilizing change, hostile to innovators, etc.—or is it about protecting the greatness of the human spirit from technologies that would parody, frustrate, discourage, and devalue its potential? [Susannah: It is the latter.] Likewise, are protests against global capitalism driven by an aversion to greatness, power, disruption, and independent agency, by ressentiment and dependence, or by a desire for greatness and agency that is frustrated by the excessive and dominating power of corporations? [Susannah: It is the latter.]

Ironically, the often ill-fitting character of the categories might prompt us to consider aspects of realities to which we had not formerly given much thought.

One key aspect of the picture that I do not think Scott sufficiently addressed is the way strong collective identities and solidarity between classes has been a way of squaring high celebration of power and excellence with affirmation of low achievers. When there are well-defined, bounded, and honoured shared identities, within which all group members have common, secure, and meaningful belonging, a group can encourage high achievement in its members, while also allowing all members, even the lowliest, to share in the glory.

The all-important requirement for the high-agency group members is that they work for the benefit and glory of the group, not merely their own. Sports are like this: people expect sportsmen to give their all for the team and they share in the glory when their side wins. Seeing the success of ‘our’ athletes in the Olympics, for instance, we celebrate their individual excellence, but also enjoy a sense of national pride, feeling that ‘we’ have won, not merely them.

Where there is a sense of being a strong and united team, where the highest achievers are striving to achieve glory for the shared identity, not merely or primarily for themselves, it can produce a much higher tolerance for the inequalities that a society that celebrates excellence and high agency produces. Where such shared identities and solidarities fail, the lowliest may fall back into ressentiment, envy, hatred, felt inferiority, and will stigmatize and seek to cut down winners. Those who see shared identities slipping away from them can feel an existential challenge along these lines.

This is one reason why many people, despite being poorer or disadvantaged, can often still love the greatness represented by a strong and assertive nation, by the majesty and pomp of monarchy, or the expanse and power of a vast empire. It connects them to something glorious, provided that they have a recognized and meaningful belonging and participation in it. However, where a felt solidarity and belonging within a greater shared project or society is lacking or failing, this can be replaced by ressentiment for many, inviting the forms of solidarity more typical of ‘ensmallening’ societies.

A strong collective identity need not be the flattening ‘collectivism’ many imagine: felt solidarity is what is most necessary. The sort of ‘ensmallening’ society Scott describes, which eschews and penalizes the pursuit and celebration of greatness can push greatness out of public and common life and into the realm of private enterprise, accentuating people’s sense of the indignity of inequalities.

Here the difference between someone like Richard Hanania and, for instance, nationalists might be considered. For Hanania and many vitalists, weak, sick, less intelligent, poor, and low-achieving people many be regarded as little more than excess human biomass. If they were to imagine an ideal nation, it would probably be extremely selective in membership, excluding, and placing little value upon many people’s lives, while privileging the most talented, rich, entrepreneurial, and powerful. More typical nationalists, by contrast, seem to regard the nation as an ennobling entity to which to belong. Its membership is largely given rather than selected or chosen. It is protected and well-defined, with members being loyal to the nation and loyal to each other. You have claims upon your nation and your nation has claims upon you; belonging to such a nation means a lot. As would be the case in a family, there is an expectation that members should have heightened levels of duty, belonging, loyalty, and concern to and for each other.

While the underlying paradigm seems rather simplistic to me, it offers a sort of illuminating caricature of certain realities, whose notable features we might gain a sharper awareness through it.

[Susannah: I think that probably one of the strangest aspects of Christianity, and the most difficult for classical pagans and contemporary Nietzscheans alike to wrap their minds around, is the way that it makes the classically aristocratic virtue of magnanimity available to all kinds of people who could not possibly have been judged as even potentially magnanimous by the standards of classical society: the widow who gives her mite in charity has a greater soul, is more queenly, than a patrician lady who gives thousands of sesterces when she has hundreds of thousands more to spare.

Nietzsche didn’t really get this aspect of Christianity: it is not in fact ensmallening. It rather embiggens everyone. It seems to be ensmallening to those who require comparison and who require immediate gratification: who will not allow greatness to be something that is shared potentially by all sons of Adam and daughters of Eve, but depend on keeping others down in order to see one’s own greatness by comparison, and who will not allow humility to be a road to that greatness - who will not allow genuine love of others to open oneself out into the world beyond one’s own good opinion of oneself.]

Breaking the Window

The ‘Overton Window’ is a largely metacontextual concept, with growing currency in various circles of both left and right, although perhaps especially on the right. The terminology is commonly used to refer to the range of political and ideological positions accepted in respectable mainstream public discourse.

As with other chiefly metacontextual concepts, it gestures at some very real phenomena. In most contexts of discourse, one will encounter strong social, institutional, and sometimes even legal pressures not to veer outside of a spectrum of acceptable opinion. The precise boundaries of this spectrum are typically vague, their constraining power on expression depending in large measure upon both the growing resistance and the unpredictability of the serious sanctions that can come upon those who dare to test them. Remaining firmly within the range of known respectable opinion is far safer than taking chances by venturing into its unmarked borderlands.

My sense is that, in its original form, the concept was 1) about the thinkability of policies, less about moral acceptability of ideas; 2) related to specific policies, rather than generalized to ideological clusters functioning across the entire field of public discourse; 3) not mapped onto a left-right spectrum. The original concept also seemed to be more designed for effective operation within institutional, political, and cultural norms, whereas now it is widely used by dissidents who do not merely want to shift the Overton Window on specific issues or policies, but to break it entirely.

When ‘the Overton Window’ becomes a generalized entity, naming not merely the window of thinkable positions on a specific issue in a given context, but the norms, values, and assumptions governing the whole field of public discourse and the persons admitted to it, dissident appropriation of the terminology and fixation upon the concept can lead to problems.

For instance, a fixation upon an Overton Window chiefly conceived of as operating upon a left-right axis can encourage those who are insecure on its borders to lurch towards dissidents and extremists without it, fearful of betrayal by their near neighbours within. This can produce polarized realignments, with a focus upon the antagonism between the left and the right and the impossibility of any stable equilibrium behind the extremes (illustrated by Robert Conquest’s so-called Second Law: “Any organization not explicitly and constitutionally right-wing will sooner or later become left-wing”). ‘No Enemies on the Right’ or ‘No Enemies on the Left’ become the watchwords, often accompanied by a desire to burn bridges that might expose people to compromising sympathies with the perceived enemy. People seek to entrench themselves in the illusory safety of a tribalism of left or right, within which extremist views have much freer circulation.

Such uses can also yield a lot more attention to people rather than merely ideas that fall outside of the Window, to those who are personae non gratae in public discourse. Yet the overlap between these two things is quite far from exact. A person who holds currently unthinkable ideas need not be considered bad and more robust—dare I say ‘liberal’?—cultures and institutions of discourse can afford the good faith, mutual trust, and shared sense of common goods required to contain more substantive disagreements within bounds. This is especially the case in contexts where parties to discourse have all demonstrated their commitment to various common goods, values, norms, and/or institutions and show civility to each other. This serves to contain ideas that might appear threatening in fora without such assurances.

Speaking of the Overton Window as a singular reified entity can further dull our awareness of just how complex and varying in kind the network of forces and norms it names is. By agglomerating everything together it heightens some people’s sense that it all needs to be burned down, with little sense of what could take its place.

Much of what the Overton Window names concerns the operations of the institutions, norms, and values of an open society, all grounded upon the tasks of those within such a society to understand, persuade, reason with, learn to live with, deliberate alongside, negotiate, collaborate, and achieve a measure of compromise and civility with people with whom they have strong differences. While these operations are clearly either lacking or in poor shape in much contemporary society—and they have their appropriate limits—the alternatives to a society committed to such operations are typically unsettling ones. When people have radically lost faith in the current public square, they can seek a refounding in the aggressive crushing of ideological opponents, with little sense of the difficult, daring, and hopeful work of peace-making required for a healthy society.

My friend Joseph Minich has spoken of the need for ‘broken family politics’, for an approach to political engagement that reckons with both the fact of our mutual belonging and the fact of our mutual estrangement, challenging us to work in good faith towards what measure of peace and reconciliation we can achieve with integrity, rather than taking the supposedly simple approach of cutting off from people with whom we differ and reordering ourselves around narrowly partisan or tribal ends. While various firm lines will still need to be drawn in such a ‘broken family politics’, we are not afforded an easy way out, but must labour in love to play our part in building a society that is also hospitable and concerned for people who differ from, disagree with, and distrust us.

‘Breaking’ the Overton Window too often means a broad rejection of good faith discourse with people who differ, of a society of irenic persuasion over force, of a whole set of moral constraints, of respectability more generally, and embracing a rhetoric and vibe of transgression.

Further, thinking of the Overton Window as something that primarily people—rather than ideas or more concrete policies—are inside or outside of can encourage a lurch towards ‘coalitions of the cancelled’, with their transgressive norms and tribal impulses against moderation and self-policing. As Scott Alexander and others have observed, if, frustrated with the censoriousness of regular society, you were to start an anti-witchhunting society, you should not be surprised to find a lot of witches would want to join you! This is how coalitions of the cancelled tend to go, as cancelled persons are as often as not cancelled with good reason and gravitate to an ethos of transgression and provocation, lacking self-moderation and increasingly having incentives that pull them towards the extremes, where more appreciative audiences and reliable associates might be found. Resistance to dysfunctional regulation of speech and behaviour can produce a reaction against such regulation more generally, or contexts that are overly hospitable to incivility and extremism. If you find yourself excluded from ‘respectable society’ and its discourses, the most essential thing is to develop highly effective internal regulation and enforced standards of behaviour and speech. Where these are not established, reactive positioning against the perceived dysfunctional standards of mainstream society can provide fertile soil for all sorts of transgression and social dysregulation.

Some of our convictions may not be things we can express directly in the public square and receive a hearing, yet it is often quite possible to communicate them less directly or in more particular contexts. It is also possible to persuade people more incrementally. Much of this is a matter of earning people’s trust, demonstrating actual concern for and attention to them, showing integrity, and concretizing our ideas in policies that are hospitable to people who differ and disagree from us. I have noted in the past the difference between ideas as conceptual edifices and more concrete policies and social visions that suggest ways such edifices might be rendered homely and habitable. [Susannah: Theology is like this as well - you can’t just dump good theology on someone, you have to help him see how it is good for him, how it can be not just abstract truth to be sucked up, but the furniture of a good home to live in.] Trying to create a society that is truly a ‘home’ for a broken family is certainly an uphill task, but it is one we must take up.

Very importantly, even were our beliefs—and ourselves as persons—thoroughly excluded from mainstream ‘respectable’ public discourse and we were to be universally hated, we should still value a good reputation with outsiders, love our enemies, seek peace where at all possible, hold ourselves and groups to high moral standards, and pursue persuasion. In such circumstances, where a wider culture of hospitality, mutual recognition, civility, and mercy has broken down, we must do what we can to create the conditions and cultivate the virtues from which such societies could reemerge within our own circles.

In many respects, this gets back to the danger of orienting ourselves in terms of imagined metacontexts. The ‘Overton Window’ and the titanic struggles between ‘the left’ and ‘the right’ can distract us from the duty and challenge of being people of virtue and forming healthy communities of practice and discourse. Metacontextual framing can imply that we must forge our habitations within the vast plains of the wider society, herding in our polarized tribes to escape the fate of stragglers (as I have argued, such a mental framework is often encouraged in people when they are overly online). However, there are many niches to be discovered, created, and developed. It is possible to form well-bounded and well-grounded communities of virtue, self-defined communities that resist destructive and compromising forces to their right and left, presenting healthy and well-regulated alternatives both to inhospitable and dysfunctional mainstream institutions and the contexts of transgression that react against them. It is also possible to form contexts of good faith conversation that are more hospitable and expansive than those that prevail in the wider society.

To achieve this, however, we need actively to resist forces that would collapse more immediate contexts, or uproot us from them: fixation with mass spectacle, with online social media, with undefined audiences in an imagined ideological marketplace, or with ideologized struggle. To counteract these forces, we must form self-regulating communities and selves, well-bounded from broader ideological antagonisms, able to be present and engaged in a wider society without being at the mercy of its influences or overly positioned—whether positively or negatively—relative to its values or its windows of acceptable discourse. Where we have our own well-defined contexts of life and discourse, we will be able to comport ourselves relative to those of a wider society more freely and adaptably, neither the prisoners nor the exiles of a metacontextual Overton Window.

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ Mere Fidelity is slowly getting back into swing, after a quiet month. We have recorded episodes on Summer Reading, on Identity in Christ, and on What Difference Does a Doctrine of Creation Make?.

❧ The Theopolis Podcast’s Deuteronomy series continues, with episodes on Deuteronomy 27: Curses from Mount Ebal, Deuteronomy 28: Blessings for Obedience, Deuteronomy 28: Curses for Disobedience, Deuteronomy 28: The Lord’s Extraordinary Afflictions on Israel, and Deuteronomy 29: The Covenant Renewed in Moab.

❧ My talk from the Theopolis Ministry Conference is now available on the Theopolis App.

❧ Theopolis has published ‘It’s About Time’, a piece of mine published in an earlier form here.

Likewise, for Jordan history has a deep unity, a conviction that shapes the way that he reads the Scriptures. His profound instinct for intertextuality is related to his sense of the character of time and history. The narratives of Scripture manifest a higher time and play out an escalating musical movement, bound together by repeated patterns in which we can perceive the interpenetration of times, and processes of remembrance and prophetic anticipation that integrate them. The sort of historiography that arises from such a sense—and reality—of history is quite different from that which arises from the flattened time-consciousness of modernity. With the loss of a sense of the reality of a ‘higher time’ and the typological character of history that follows from it, realities such as ‘distance’ in time assume a radically different character. Considered in terms of a higher—or deeper—reality to time, it should be clear that the intervention of two thousand years could never separate our time from the presence of the once-for-all events of the cross and resurrection of Christ!

❧ The Davenant Institute has published my recent ‘Beyond Rules and Roles: Scripture and the Sexes’ series on SoundCloud.

❧ Seraphim Hamilton invited me to join him for a discussion of reading the Bible, sharing our appreciation for the work of James Jordan.

❧ I joined Michael Halcomb for a GlossaHouse podcast conversation on typology, politics, love, and much else besides.

❧ My latest God’s Story Podcast episodes in the Zechariah series are on Zechariah 3 and Zechariah 4.

❧ I also did a God’s Story Podcast episode on the controversy surrounding the Last Supper scene in the Paris Olympics opening ceremony.

Upcoming Events

❧ Alastair’s next Davenant Hall course is now open for registration!

Christian accounts of male and female are often limited in the degree to which they engage with sources outside of the Bible and the Christian theological tradition. Yet, in the absence of such engagement, our perception of the Christian teaching can be distorted; it can be regarded as an alien imposition upon nature and society, rather than as something that operates with the grain of creation and serves to illuminate it.

The course will study ways in which a Christian account of the sexes can engage both receptively and critically with an array of fields of enquiry, from philosophy to anthropology to the natural sciences.

❧ Most of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Alastair and Susannah

A definite ice cream theme in this one. You should have gotten a photo of yourself eating ice cream whilst in the regency frock coat, to rub it in with the wife.

An entire novel could have been written about Harrison's waiting for his bounty to be paid out, and the intransigence of Parliament in that affair. (By the way, bounties would be a very effective alternative to copyright and patent laws, which are biblically questionable.)

There's a lot to mine in the theme of master/slave mentalities. The pagans have done some interesting work on it. I like to map the parable of the talents overtop of it; that makes for some interesting parallels. The slave mentality maps onto the "God is stingy" mentality very nicely, along with the economic ideas such as high time preference behavior.

Here is what I found to be a stunning example of how metanarratives like "negative world" can be turned topsy-turvy simply by changing the context. So, the fella who wrote that original essay sits in the context of a privileged, college educated white male writing for an elite magazine. And, in his metanarrative, Christianity is privileged and assumed in his ideal past.

But what about somebody sitting right smack in the middle of that ideal past, such as Sybil Jordan Hampton, one of the first black students to go back to Little Rock Central High School after the famous Little Rock Nine first integrated the school in 1957? Did her context feel like "Christian positive world"?

(Hat tip to David French for that one.)