Susannah: In addition to work, the main thing that I’ve been doing over the past couple of weeks is basking in friends: we have dear friends in the UK, but my strange and varied set of overlapping friend-Venn diagrams in NYC are my social home. I tend to want to go out a good bit more than Alastair; we’ve developed something of a system, where he has a certain number of social points in his weekly account, and I need to decide where to spend them. I used to think I was an introvert. I now know, by contrast with my husband (who is nostalgic for lockdown when, at one point, he didn’t share a room with another human being for three months), how wrong I was. It turns out I’m an extravert who just likes to read.

Work: The technology issue is nearly at the printers! I’m so excited about this one. I commissioned and edited, among other things, two pieces on AI/ChatGPT/Large Language Models, one addressing the philosophical issues around the immateriality of the intellect and what it is that computers can and can’t in principle do (he makes a very strong case that not only can’t computer programs not “write,” they also can’t do math!) and one by a woman who works specifically with LLMs as a researcher, who gives an excellent overview of what the technology actually does, followed by an absolute jeremiad against outsourcing good human tasks to it. Links to follow in the next substack, but I’m so excited about this issue at the moment that I have to give you a preview of coming attractions.

Writing: One of the things that keeps happening was that people contact me about one piece of mine in particular which spoke to them. The dear friend we met up with for smoothies in midtown today said the same thing. It’s not the fanciest or most erudite piece I’ve ever written, but it seems to be one that helps people, and so because I wrote it before we started the Substack and it’s never made its way in here, I thought I’d link it. It describes my struggles with scrupulosity - religious OCD - and the way that I have come through them - the way that God used even that to help me know him better and trust him more.

Alastair: I am unsure whether we have ever gone so long without a Substack post: it is not far off a month since we last published something here. We have mostly been in New York, keeping busy with various projects, teaching, writing, and events.

Having lots of friends and family in the US and the UK, we never feel able to spend as much time with people as we would like; we are constantly torn between many commitments and connections and there is simply not enough of us. This is particularly the case when it comes to our churches, especially as, even when we are ‘around’, we are often travelling. However, the time that we do get is delightful and we have greatly appreciated reconnecting with various people here.

Our weeks have been punctuated by a variety of meals, meetings for coffee, board game evenings, and video evenings with various friends and friend groups. I mostly abstain from the social whirl, but, besides the things already mentioned, Susannah keeps a full calendar!

Since our last Substack, we have also made several new acquaintances and met several people in person whom we had only previously known online. For instance, we were in a neighbourhood bagel store a few weeks ago and a woman came up to Susannah and asked whether we were Susannah and Alastair Roberts. It turned out that she and her husband read Plough and listen to my podcasts. Her husband, whom we met outside the store with a couple of their sons, is also going to be officiating at the wedding of some friends of ours later this month. The Upper West Side really feels like a village sometimes! [Susannah: We’ve got about ten couples who are good friends, or new friends on their way to being good ones, within a half-mile walk.]

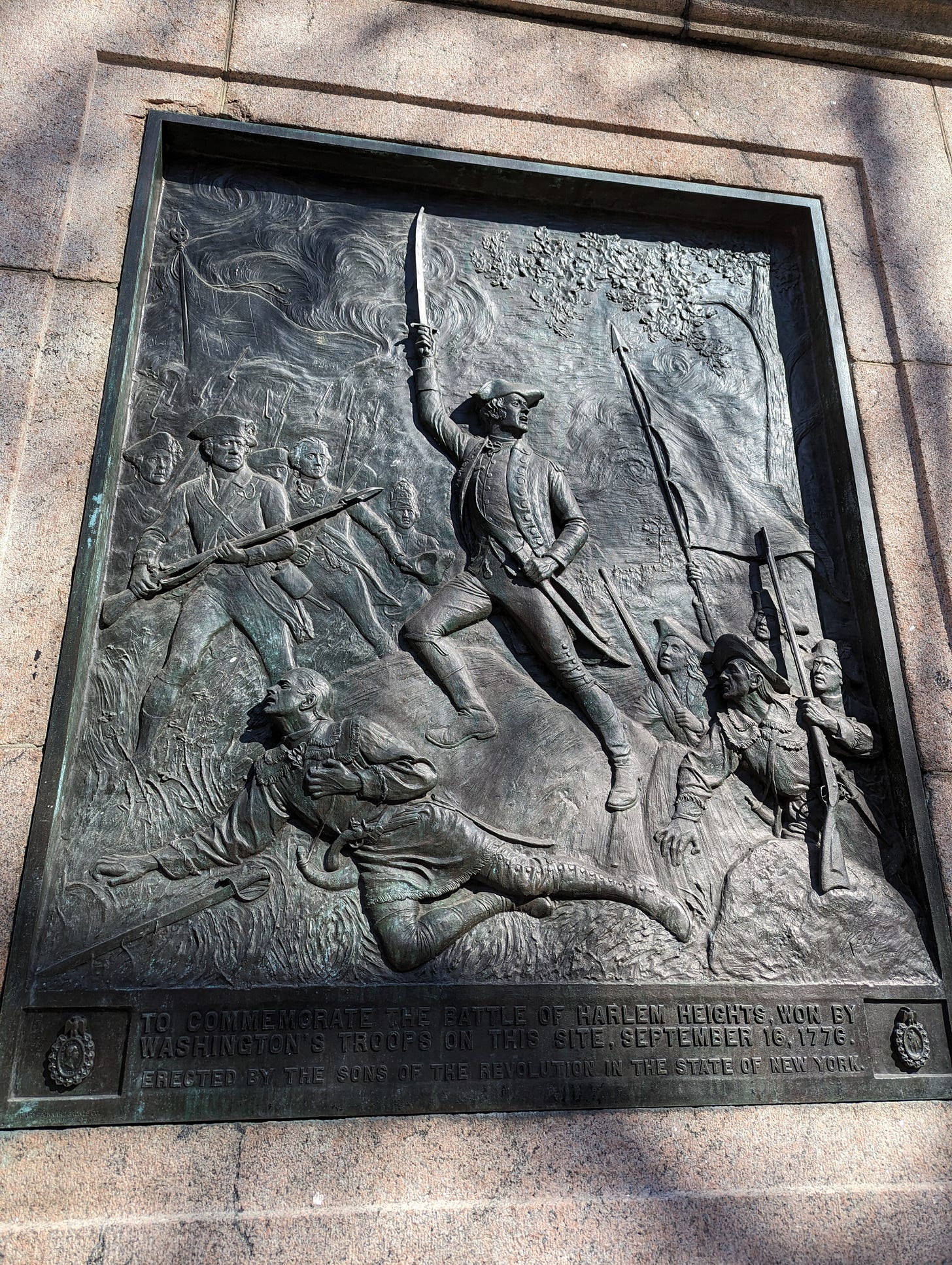

Our neighbourhood has also been in the news with the protests at Columbia. We had a walk up there and back through Riverside Park just over a fortnight ago.

On the 23rd, we had the privilege of seeing Derek Rishmawy, our dear friend and my fellow cast member on Mere Fidelity, for a very early breakfast. I was flying out later that morning, so needed to leave for Newark Airport by around 8am. However, as Derek had arrived in from California the preceding evening for Keller Center responsibilities, I did not want to miss the opportunity to meet up with him, as I had not seen him for a few years. Unfortunately, I missed the chance to spend time with Andrew Wilson, another cohost, and the cowriter of Echoes of Exodus.

Susannah had the opportunity to spend time with Derek, Andrew, and other friends over the rest of the week. However, I had to fly out to San Francisco, where I had a conference at a church for two days.

The conference was wonderful. Besides the welcome and hospitality I enjoyed from the church and my hosts, it was an encouragement to get to spend time with many faithful Christians there. I was also blessed to meet up with several online acquaintances and friends whom I had not yet met in person, including one online friend who had met two of my brothers nearly two decades previously!

New York in the spring might be New York at its best. The sun is shining in a cloudless sky, the cherry blossom is out, people are picnicking, playing ballgames, and relaxing, and there are few things that I would rather be doing than meandering through Central Park with Susannah.

We have been doing a lot of walking in the Park and elsewhere lately, often ending up at a bookstore. As a Bible scholar, I often enjoy visiting one of our local Judaica stores; it is stimulating to read commentaries from gifted scholars from a tradition quite distinct from one’s own.

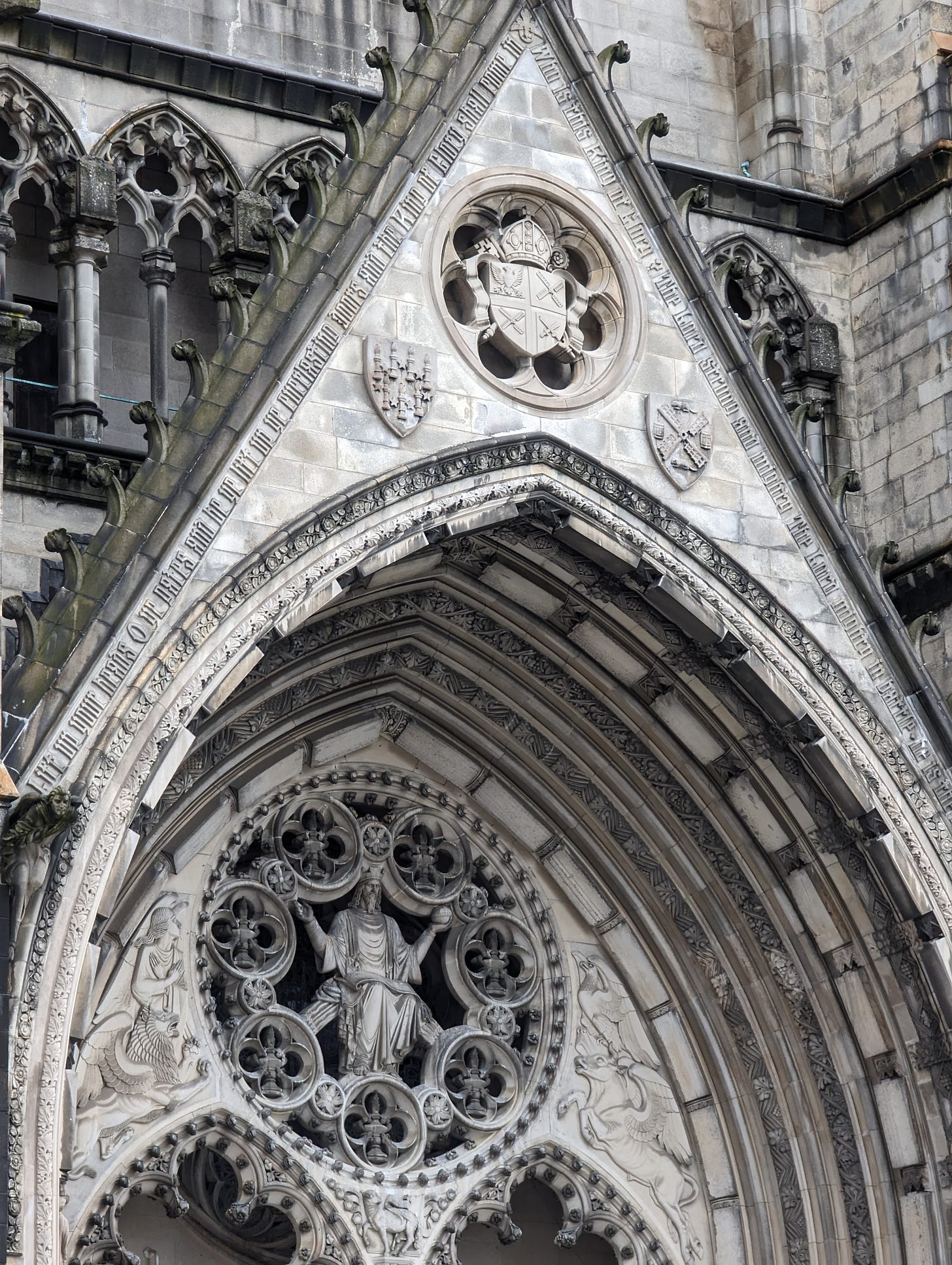

This Sunday morning, the bishop visited and confirmed seventeen candidates at our church, including a friend of ours. Being part of such a faithful and loving congregation is one of the best things about our life in NYC. We celebrated our friend’s confirmation with a meal, followed by meeting up with another friend in the city and walking back home in the sunshine.

Looking ahead, tomorrow is our second wedding anniversary, we have a trip to Birmingham in just over a week’s time (the one in Alabama, not the Venice of the West Midlands) for a colloquium on political theology, a wedding in New York on the day after our return, followed by a trip in Ireland. A lot to look forward to!

The Internet is the Negative World

Aaron Renn’s ‘three worlds’ model of American secularization has received considerable attention since his article ‘The Three Worlds of Evangelicalism’ was published in First Things. This attention was heightened with James Wood’s subsequent use of it in his critique of the ‘winsome model’ of cultural engagement, chiefly associated with the late Tim Keller. In the two years that have followed, the so-called ‘negative world’ account of evangelicalism’s current position in secularizing America has perhaps chiefly become associated with the faction of evangelicalism that John Ehrett has termed the Pugilists, who have commonly wielded it to justify the adoption of a more belligerent posture, both with respect to the surrounding culture and towards moderates in the Church.

Earlier this year, Renn’s Life in the Negative World: Confronting Challenges in an Anti-Christian Culture was released by Zondervan. It was only released last month in the UK, so I had to wait to get my hands on a copy, but I finally had the opportunity to read it and would recommend that others do the same. Renn’s diagnosis of evangelicalism’s current situation is often perceptive and his suggestions for responses are worth considering. Despite the great currency that the ‘negative world’ model has had among many culture warrior types, while he gives them appropriate credit on certain points, Renn’s proposals do not align with theirs and will also be appreciated by many who would decisively part ways with the culture warriors.

Renn’s analysis of contemporary culture is often helpful, not least because such analysis addresses glaring gaps and dangerous blindspots in much evangelical thought, with its narrower preoccupations. As Renn recognizes, much evangelical thought is unaware of how shifting sociocultural contexts shape its thought, ecclesiology, and practice, approaching these things as if they operated within a purely ideological framework. He observes, for instance, the way that ‘complementarianism’ and ‘egalitarianism’ must be understood against the broader backdrop of modernity and of sociocultural developments in America over the last fifty years. As someone who has been stressing such points for years (and is currently teaching a course on modernity as the under-considered backdrop for our thinking on such matters), it is refreshing to read a clearer-eyed treatment.

In outline, Renn’s ‘three worlds of evangelicalism’ model is a sociological account of shifts in American society over the last sixty years as they concern its hospitality to historic evangelical faith. Renn’s account, while perhaps providing a useful framework for Christians elsewhere and of different traditions, is especially focused upon evangelical Christians in American society. Its purpose is also less one of providing close historical or social analysis than it is equipping evangelicals to operate more effectively in a transformed and transforming cultural environment. For this reason, while someone seeking close analysis could fault it as simplistic at several points, for its intended purposes, such simplicity is generally a virtue.

In broadest outline, Renn’s account periodizes the past sixty years of American history—a time of decline for Christianity’s influence in America—into three eras, of thirty years, twenty years, and ten years. The first, from 1964 to 1994, he calls ‘positive world’, an era within which wider American society mostly had a positive regard for Christian faith and morality, and there was a general alignment between Christian norms and the aspirational norms of society at large. The second, from 1994 to 2014, he terms ‘neutral world’, within which, although Christian faith no longer enjoyed the same privilege that it once did, it faced little hostility or discrimination either. The third, an era beginning in 2014, which we still inhabit, is ‘negative world’, within which historic Christian beliefs and morality are increasingly at odds with dominant social norms and mores, exposing many Christians to negative consequences for their convictions.

Renn enumerates several factors that occasioned the decline of Christian influence in American society and the growing disfavour towards evangelicals: the collapse of the old WASP establishment, the social and sexual revolutions, the end of the Cold War, and factors such as corporate consolidation and the move to a digital world that allow for a few dominant corporations and agencies to exert immense social and cultural control and influence.

In Renn’s telling, American evangelicalism first arose in the 1940s and filled the gap between the liberalized mainline and the fundamentalist churches, with many of the fundamentalist churches later being absorbed into it. While fundamentalism tended to be more sectarian, and socially marginal, evangelicalism became a powerful social and political force as it catered to more culturally and socially engaged conservative Protestant Christians, typically from the middle classes.

Renn discusses some of the chief forms of engagement with wider society that evangelicals have adopted. The ‘culture warrior’ approach, exemplified by the ‘Religious Right’ and the ‘Moral Majority’, adopted a combative posture to the forces of secularization, representing the activist grassroots of movements against such things as abortion and perceived attacks upon the family and conservative sexual mores. Renn characterizes the ‘seeker sensitivity’ model of cultural engagement as ‘a business school approach to Christianity’. Typified by the suburban megachurch, this model of cultural engagement presumed a widespread latent interest in Christianity in people that, with a more appealing and consumer-driven model, could be activated and attracted into church.

While both these models flourished in the positive world era, whose more favourable conditions they largely depended upon, a third strategy of ‘cultural engagement’ responded to the challenges posed by the neutral world. Christians could no longer count upon cultural openness or tractability to their message, or significant prior exposure to Christian ideas, and increasingly needed to win a hearing for themselves. This model tended to be more delicate in its handling of points of cultural tension and wanted to build bridges with and maintain presence within broader social institutions. This model of engagement, typified by someone such as Tim Keller, was more commonly found in urban and professional settings.

Although Renn draws some connections between these approaches and those of H. Richard Niebuhr’s Christ and Culture, he wants to make clear that the contrasting approaches of engagement did not develop within hermetically sealed theological frameworks, but were highly responsive to people’s contexts and class positions. Geographically, for instance, the culture warrior model was most dominant in rural and lower-class contexts, the seeker sensitivity model in middle-class suburban settings, and the cultural engagement model among urban professionals.

Most of Life in the Negative World consists of proposed personal, institutional, and missional responses to the ‘negative world’ situation. I do not intend to give a proper review of the book here. I recommend that you read it for yourself: it frames an increasingly important conversation and makes some helpful suggestions. In what follows, however, I wanted to share a few of my own reflections upon it and some of the random thoughts that I had arising out of it.

Renn’s three worlds framework might suggest to many readers that it describes a straightforward linear development, focused upon Christians. The framework is a rough heuristic designed for Christians, not a detailed model of broader social developments: a seeming linear movement has the advantage of simplicity. However, despite the benefits of this, it might leave us less alert to uneven and discontinuous shifts characteristic of multicausal developments. Further, by placing Christians at the centre of the picture, it might disguise the true nature of some of the changes.

As Renn’s framework is centred upon Christians and an unfolding cultural conflict between them and ascendent antagonists, his account is poorly positioned to recognize certain more ‘ecological’ shifts. Such ecological shifts can be discontinuous—involving the sudden introduction of new factors, which do not merely continue existing trends—and, although they may often advantage opponents of Christians, were not really engineered or targeted by or at anyone, and can hurt other groups in similar ways to Christians.

There is one huge missing piece in Renn’s account, its absence both glaring and baffling. While he rightly mentions the importance of digitization, which concentrates great power in a few online companies, he simply does not adequately wrestle with the impact of the Internet. Without considering the Internet, I do not believe that much of what Renn terms ‘negative world’ will truly make sense. Indeed, key inflection points in the wider adoption of the Internet coincide with some of the shifts that Renn identifies: global Internet use took off in the mid-90s and it was in the mid-2010s that the age of the mobile Internet arrived and social media reached its dominance.

The shifts to neutral and negative world are certainly not monocausal, but I believe that the Internet is by far the more powerfully explanatory factor. The following is a rough sketch of some of the relevant ways in which I believe that its impact has played out:

The early Internet radically changed the form of public discourse. Whereas broader cultural discourse had formerly been the preserve of a few, a realm protected by gatekeepers within elite institutions, publishing, media, and politics, the Internet started to open the conversation up further. As a growing realm of discourse, the Internet reduced the control of legacy media, the political and party establishments, academic institutions, and other such agencies, and the power of old liberal elites at their heart.

Within the former cultural ecology, liberal elites were less threatened by hostile and unwelcome voices, which could more safely be siloed outside of mainstream discursive contexts or policed within them. The obscurity that people could enjoy outside of such mainstream discursive contexts was also a source of safety for them. To become a public voice, you would need to pass through credentialing and other gate-keeping institutions and agencies and demonstrate some degree of loyalty to the norms of the liberal establishment that they constituted. In many ways, this allowed for a more generous Overton Window. Liberalism’s confident culture of good faith and respectful disagreement was easier to maintain in a context where participation in public discourse was more reserved to those who had undergone extensive formation in its institutions, belonged to its elites, and honoured its norms, while more fringe or plebian voices lacked the same access to publicity and could safely be ignored.

While people might have strong differences, they shared institutions and a broader liberal culture in common and were less likely to be seeking to destroy each other or burn it all down. In such a setting, despite political, religious, and ideological differences in society, there were still effective consensus-forming mechanisms and institutions, elite control over the dominant means of publication, and a confidence in a culture of persuasion.

Legacy media, with its gatekeeping and credentialing, could restrict participation in the public to persons with formation in liberal discursive values, but the Internet changed this. Whereas positions might formerly have been represented in public by more erudite and polished advocates, the Internet opened realms of conversation in which differences could be discussed by the average Joe. Now people could talk more directly with people of different viewpoints.

The earlier Internet was dominated by more intellectual, creative, and technologically literate males, who developed their own fora and typically male-coded cultures of argument. The liberal dream of a culture of persuasion began to sour in this context, however, especially as less intellectual persons started to go online (Scott Alexander describes this dynamic in this post, to which I will return later in my discussion). People who had hoped for thoughtful and friendly debate encountered flamers, trolls, and fools. Instead of interacting with thoughtful exponents of different positions, you might unwittingly find yourself arguing with some anonymous obnoxious fourteen-year-old. Some of us might have been that fourteen-year-old.

The world prior to the Internet was one in which people of different contexts were far less visible to each other. People could live within their own bubbles, with much less exposure to people and ideas outside of them. The Internet, however, started to pierce a lot of these bubbles, enabling people to look beyond their social worlds and to be formed in ideas and values and engage with people from outside of them. This weakened the power of those worlds to maintain internal norms and consensus; it also made it easier for dissidents to arrange movements within and against them. It also started to make formerly obscure bubbles easier for outsiders to look into. Among other things, these shifts increased the felt need for apologetics, for both outsiders and insiders. It also intensified the perceived threat that different bubbles could pose to each other.

It was in such a context that a strong atheist movement started to emerge. More young people from Christian contexts were rejecting the bubbles in which they had grown up. And, especially following 9/11, more secular atheists were starting to look at the religious worlds of many of their compatriots as a threat. The belligerent New Atheist movement was a product of the earlier Internet culture, strongly male-coded and debate-driven. Alexander suggests that a loss of confidence in the power of persuasion led people to look for a ‘hamartiology’, an account of sin. The New Atheists came to believe that religion was at the root of people’s blindness and resistance to reality. They were strongly committed to the hard sciences and to a world of facts and reality. While very aggressive, they still tended to uphold liberal values of open discourse: “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.”

It seems to me that the rapid passing of New Atheism as a movement might be a difficult thing to explain within Renn’s three world framework. In the early 2010s, atheism discourse was everywhere online and then suddenly the movement failed and many of its leaders fell into disfavour. What happened? Alexander suggests that the New Atheist movement ‘seamlessly merged into the modern social justice movement’, the hamartiology of the latter replacing that of the former. I think that Alexander is right that New Atheism largely shifted into social justice. However, I do not think that he adequately accounts for the mechanisms by which this happened: I think that the evolution of the Internet provides a far better explanation.

The key shifts occurred around the time that Renn locates the movement into negative world. The earlier Internet had chiefly been a realm of words and ideas. Although there were intense circles of feminine-coded online activity, more masculine forms and cultures of discourse generally tended to be more defining of the Internet as it related to the ‘public’ realm (the ‘there are no girls on the Internet’ meme belongs to this era). The rise of social media radically changed the culture of the Internet. While the former Internet had been more anonymous and detached from offline identities and relationships, in the new social media age everyone was increasingly putting themselves online. Whereas the Internet had been a weird place with lots of anonymous strangers onto which you could go, now your real-life identity and relationships were online. It was no longer a Wild West into which you could wander or a secret friend to whom you could confide, but a virtual village in which you resided.

The earlier Internet was also decentralized and unmapped, filled with obscure corners where you could find groups of strangers who shared some interest. Or you could set up your own online homestead with a blog, perhaps joining some friendly circle of fellow bloggers. The social media Internet completely changed this. In place of subscribing to RSS feeds, on the social Internet things were disseminated socially. ‘Virality’, ‘memes’, social media ‘mobs’, and other such concepts tried to wrestle with the novel results and forms of the emerging dynamics of the social Internet, where ideas spread along more tribal, reactive, and emotional trajectories.

The social Internet made formerly obscure parts of the Internet visible to each other, collapsing formerly detached spaces into vast common planes of discourse, within which we were all potentially visible to everyone. In the social media Internet—which would be intensified by the mobile Internet—the distinctions between public and private, and those between political and personal started to fail.

Before the advent of the social Internet, there were also strong feminine-coded worlds online. In particular, the worlds of fandom and fan fiction. The Internet gave a powerful voice to fan communities, who obsessively talked about, speculated concerning, created artwork relating to, and spun off their own fantasies from their favourite properties. Especially for young women, such contexts were realms within which they could theorize their identities, relationships, and worlds. The intimacy of the things that a young woman could confide of herself in such realms also gave them a social intensity and fierce protectiveness and sensitivity. Katherine Dee (Default Friend) has argued that it is impossible to understand the cultural shift to so-called ‘wokeness’, or what Wesley Yang has called the ‘successor ideology’, without appreciating the role that Tumblr in particular played. Tumblr was a step away from the more obscure worlds of earlier fandoms into a more visible and open world.

I think Dee, perhaps the most perceptive commentator on such Internet subcultures, rightly appreciates the importance of Tumblr. However, it seems to me that the mainstreaming of Tumblr culture required larger social media such as Facebook and Twitter, which brought masculine and feminine forms of the Internet into more direct contact and collision with each other and led to the dynamics of the latter prevailing over the former.

The immense popular user base of Facebook and the widespread use of Twitter among the commentariat, academics, and other public figures gave them immense power to shift the tone of the broader cultural conversation as platforms. And their social character meant that there was a concern for personal identity, relationships, and communal dynamics within them that one would not encounter to the same degree in former public realms. The intense self-reflexivity and theorization of identity and society encouraged by Tumblr and other such contexts could break out into the broader culture because Facebook and Twitter created flattened contexts of discourse, disrupting the oppositions between public and private and political and personal that would formerly have limited the spread of its discourses.

As social media increasingly swallowed public discourse, it led to a growing preoccupation with the fragilized and bespoke identities of those who came of age online. Whereas the old context of liberal discourse was gatekept and bounded, distinguished from more social spaces, and operating according to more masculine-coded norms, the new discourse, occurring in social places, became preoccupied with feminine-coded sensitivities about identities, victimhood, and etiquette. The structurally egalitarian character of the new social media also made it very easy for authorities to be challenged and unsettled through group pressure. It made it a lot easier for marginal groups to organize across contexts, to make themselves visible to themselves and others, and to exert pressure upon majorities. The intense fandom culture also encouraged the rise of a fixation upon media representation of various groups and identities in various properties and powerful lobbies to press for them.

Without the advent of social media, the shift to social justice and its more feminine-coded politics would probably not have occurred in the same way. In the New Atheist movement this shift initially played out in controversies such as that surrounding ‘Elevatorgate’ and in a migration of focus from discourse focused upon scientific and philosophical realities to its own internal dynamics and to issues of ‘social justice’: feminism, antiracism and racial justice, and the various concerns of the LGBTQ+ movement. The concerns of this politics were concerns that were more natural to an age dominated by Spectacle, where appearance and representation have increasingly taken the place of ‘everything that was directly lived’, and the personal and political are elided.

In this context, the old confident liberalism has failed. The once bounded public square is bounded no longer. The participants in society’s discourses—at all levels—increasingly appear as victims and vulnerable persons requiring protection. A public square to which people are more directly exposed and in which they can more directly operate (perhaps to be followed by its evaporation) has set the stage for the passing of a culture of robust exchange of differing viewpoints, confident in a common reality.

Much of the old liberal establishment has withered and lost its former confidence. The legacy media has shrunk and its authority diminished. Academics are more precarious in their employment and more conformist; there has been a rapid diminishment of political diversity in academia. Academic institutions are increasingly driven by the interests of administration and business. The old realms of the public square have been weakened and what has taken their place operates very differently, a small number of corporations exerting considerable power over it. More restrictive managerial oversight of societies without consensus reality but with repeated alienating and polarizing interactions is taking the place of the more open liberal societies of the past. Power has shifted to large corporate agencies, untrustworthy custodians of liberal values. The Overton Window is no longer the more expansive one of the old liberalism, but one that serves the interests of a new managerial elite, brokers of a social order for their dependent and biddable clients, whose constant petitioning of them in the hyper-politicized symbolic causes of their personal lives is rather less threatening than traditional politics might be. In many respects, it could be regarded as a depoliticization of people, so that the market can proceed unobstructed: ‘neoliberalism is social justice’.

In the deluge of data characteristic of the Internet Age, the fact has died and, in its place, we have multiple competing narratives, with little allegiance to a grounding reality. The politics of such an age of spectacle and social media will tend to be ‘scissor’-politics, repeated narrative-driven polarization (Floyd, COVID, and Gaza are examples of such stories). In such a context, disdain, anger, resentment, and cruelty will tend to proliferate. Its reactivity will also encourage competing extremisms. Trump was a symptom and accelerant of such politics, among other things designed to attack the dignity that liberals might see in the office of the presidency.

There is a great deal more that could be said about the impact of the Internet. However, I want to consider how it might relate to Renn’s negative world thesis. The development I have described weakened an old liberalism, reordered societal discourse, transformed the public square, elevated more feminine-coded values, fragilized communities and identities by making them more porous and exposed, thrust more of societal life into a collective Spectacle, and strengthened managerialist neoliberalism. It was not targeted against Christianity, though.

In many respects, we all live in a negative world now. The loss of consensus reality, the failure of effective consensus-forming institutions, the extreme polarization of our politics, and the fragilization of our communities and identities leave everyone feeling exposed and vulnerable in new ways. No one thinks that they are winning. In other respects, the development has fallen especially hard upon particular groups. In America the place that Jews once enjoyed in the old liberal establishment, for instance, is rapidly shrinking and rising open antisemitism and less certain government policies concerning the state of Israel are signs of a loss of their cultural power.

In such a context, it is easy for people to confuse some of the ways that the emerging order seems to threaten their groups with some ‘negative world’ hostility to the Christian faith. Responding to such a sense, it is easy for identitarian victimhood politics to elide Christian identity with fragilized cultural identities—with ‘white masculinity’, for instance—and to pursue sectarian politics in Christ’s name. As such politics impact the Church, they will tend to be both highly divisive, resistant to the Church’s concrete catholicity, and to compromise the moral integrity of the Church and the primacy of its bonds for the sake of effective political coalitions. Accentuating political tribalism offers a sort of security for anxious Christians, but at the cost of Christian faithfulness in preserving the peaceful bond of the Spirit in the Church.

A key reservation I have about Renn’s thesis is that it might lead us to focus our attention upon ourselves and upon American society’s reduced hospitality to Christians and their faith. This is not without importance, but, in many respects what we are experiencing may be a particularly pronounced form of a more general societal malaise, much of it brought about or accelerated by the Internet. Recognizing this might equip us to think better about the manner of our response. For instance, we might think more carefully about how to guard our own lives, contexts, communities, and organizations from some of the more damaging dynamics of the Internet. We might also consider how the Church might function as an Ark for others, protecting them from the collapse of the former order and the threats of its successor.

In conclusion, I want to stress that the advent of the Internet is far from a monocausal account of the so-called ‘negative world’ and that I agree with most of Renn’s analysis of its causes. However, the absence of serious reckoning with the Internet in his account is a significant oversight.

Ascension in John

Thursday was the Feast of the Ascension and, in the days leading up to it, I found myself reflecting a lot upon the distinctive theology of the Ascension in John’s gospel.

Unlike (the longer ending of) Mark and Luke, John does not directly record the event of the Ascension in his gospel. However, as is also the case for Jesus’s baptism, the Transfiguration, and Pentecost, the absence of an account of the Ascension certainly doesn’t mean the event is absent from John’s gospel. There is no gospel that gives greater attention to the Ascension than John’s does!

Indeed, one could even argue that, as with the Transfiguration, without a single episode of Ascension in John’s gospel, the entire gospel can more readily bear the traces of it. Without a single focal episode, it all is an account of Jesus being ‘lifted up’.

John has a rich theology of Ascension. Jesus came into the world (1:9) and the Ascension would be his going out of the world (17:11). His descent is a coming from the Father and his ascent a going to the Father (16:5). The Ascension is the royal lifting up of Christ, his exaltation as King, but also as unifying spectacle. The Ascension is the glorification of Christ, a manifestation of the glory that he had from the beginning.

The Ascension would be a demonstration of the truth of Jesus’s descent as the bread from heaven (6:62). The Ascension is Jesus’s going away (16:7) to prepare a place (14:3) and to come to his disciples in a new manner. In John 17 we have an almost proleptic—‘I am no longer in the world…’—presentation of Jesus’s intercession for his people, a presentation that perhaps offers us a glimpse into his intercession for us at the Father’s right hand.

Such multifaceted descriptions of Ascension protect us from a flattened vision of it, or merely regarding it as an isolated miraculous episode or a simple relocation. Instead, we have a rich theology of Ascension, stressing its manifold relational, cosmic, political, and redemptive import.

The Descent and the Ascension of Christ open up a conduit from heaven to earth. He is the ladder upon which others ascend and descend (1:51). Through his Ascension, he is the Way to the Father, so that we too might go to where he went (14:6).

Ascension theology is everywhere in Revelation: it’s a book of things and persons going up into and down from heaven. Chapters 4-5 are the Ascension from above, from the vantage point of heaven, reprising Daniel 7. Jesus is the one who ‘comes with the clouds’—to God’s right hand. Revelation 12 is another key passage: “She gave birth to a male child, one who is to rule all the nations with a rod of iron, but her child was caught up to God and to his throne...” With Christ as the ladder, heaven can descend to earth, as we see at the end of Revelation.

John’s presentation of the Ascension in his gospel and Revelation integrate it into his treatments of Christology, eschatology, pneumatology, soteriology, ecclesiology, theology proper, political theology, and much besides. If we have been reading him carefully, by the end of John and Revelation, the reality of the Ascension should be clear to the eyes of faith and its import should impact us on several fronts.

Meeting with her in the garden after his resurrection, Jesus says to Mary Magdalene in John 20:17: “Do not cling to me, for I have not yet ascended to the Father; but go to my brothers and say to them, ‘I am ascending to my Father and your Father, to my God and your God.’”

Reading the gospels, we might sometimes wish for the sort of tangible and immediate physical presence the disciples enjoyed, for the assurance of sight. However, in our Lord’s word to Mary, the ‘clinging’ that may be characteristic of a desire for tangibility and visibility is discouraged. Rather, with Mary we must recognize the goodness of our Lord’s ‘going away’, recognizing the place to which he has gone: to the Father’s right hand, to receive all authority and power, to intercede for us, and to pour out his presence upon us in the bestowal of his Spirit.

Nevertheless, Mary’s posture is not simply rebuked and rejected. While we must not cling, in faith we nonetheless still reach out for the tangible and visible presence of Christ. In the current age we seek for the powerful manifestation of his gracious and good rule among us and, in our longing for the age to come, his physical return in glory.

Come, Lord Jesus!

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ Mere Fidelity recent episodes are on Men and Women in 1 Timothy, Thinking For Yourself, The Deception of Isaac (discussing issues raised in our previous Substack), and Casuistry.

❧ The Theopolis Podcast’s Deuteronomy series continues, with an episode on Deuteronomy 25: Disputes, Stripes, and Ox Muzzling.

❧ You can watch the videos of my Beyond Rules and Roles talks in California on YouTube.

❧ Plough published a piece of mine: Why I Went Cold Turkey on Political Theology. I discussed it in a Twitter space.

❧ Susannah, Derek Rishmawy, and I did a podcast on Conspiracy Theory and Autodidact Brain.

❧ My friend Andrew Wilson republished two articles of mine that are nearly twenty years old(!), on wine in communion: The Case for Wine in Communion and Wine in Communion: Questions and Responses.

❧ My biblical reflections project was mentioned in an article on Christianity Today.

Upcoming Events

❧ We will be attending a Theopolis Civitas colloquium in Birmingham, Alabama next week.

❧ Most of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Alastair and Susannah

As someone who has been on the internet since 1996—strictly speaking not “early,” but early enough by the standards of the wider culture—I have occasionally struggled to explain to people how the Internet of the late-Nineties and early-Aughts differed from the one we see today. Now I will simply refer them to the section of this newsletter subtitled “The Internet is the Negative World.”

First, on Renn's hypothesis, I can't help but wonder how much is impacted by a confirmation bias. What you look for is what you get. How you treat others is how you will be treated. Which is related to Keller's approach. Being winsome is arguably just treating people with neighbourly love.

Also, I think the timing of the cultural shifts are quite regionalized and there's an urban-rural divide too. In central Canada, arguably we've been neutral since the seventies, and negative since the nineties. Quebec was probably earlier yet. In fact, most contemporary French-Canadian crude language is religious rather than sexual, which may indicate the strength of their anti-religious feelings.