№ 24: Running with Scissors

Durham, York, London, and a wintry Stoke-on-Trent

Dear Friends,

Alastair: Every two years, Durham hosts the Lumiere festival, for which the city is filled with a variety of light displays. I have attended every year the festival has been in Durham and, as I wanted Susannah to experience Lumiere, to spend time with our godson, and to catch up with several good friends, we went up to Durham for a visit.

There have been some remarkable installations in previous years. In my estimation, some of the most exceptional installations from past years include the immersive For The Birds installation in the Botanic Gardens, some of the cathedral projections such as Crown of Light or World Machine, the 3D projection of a breaching baleen whale in the river of Mysticète, Keys of Light at Rushford Court, or the ‘I Love Durham’ snowdome formed around the statue of the Marquess of Londonderry in Market Square.

This year’s Lumiere—at least what we saw of it—was not up to the standard of some previous years. Most disappointing was the absence of music and sound in most of the outdoor installations, especially as sound was integral to many of the best displays of previous years.

Nevertheless, it certainly was worth visiting. Pulse Topology, for instance, an installation in the cathedral for which the heartbeats of a few thousand participants were projected into a canopy with a great pulsating array of light bulbs, each light representing one participant, was remarkable.

We stayed in Durham until the Friday evening after Lumiere, working through the week, while making the most of the time in one of our favourite places. We also had several coffees, meals, walks, and chats with friends and acquaintances from the Durham area, both old and new. Susannah and I have also been wanting to play more board games and we were able to play several with our godson during our stay.

[Susannah: The idea that Durham could possibly do anything to make itself more impressive is bananas in any case. It’s a city like a castle in its own right, and the Cathedral is the most beautiful building you’ve ever seen, is a thousand years old, and contains the bodies of St. Cuthbert and the Venerable Bede—what, you want MORE than that?

Anyway, Alastair also fails to mention that we watched Napoleon with our godson, which was… I mean, what it mainly did was make me want to re-watch Master and Commander, which just had its 20 year anniversary, so we did that over the weekend. Boy, does it hold up. Likely my favorite movie.]

As the weather was very good on most of the days of our visit, I walked throughout the city, revisiting several of my old haunts and favourite parts. Every time I visit, I am reminded of how astonishingly beautiful Durham is, how fortunate I was to live there for so long, and how much I miss many things about it.

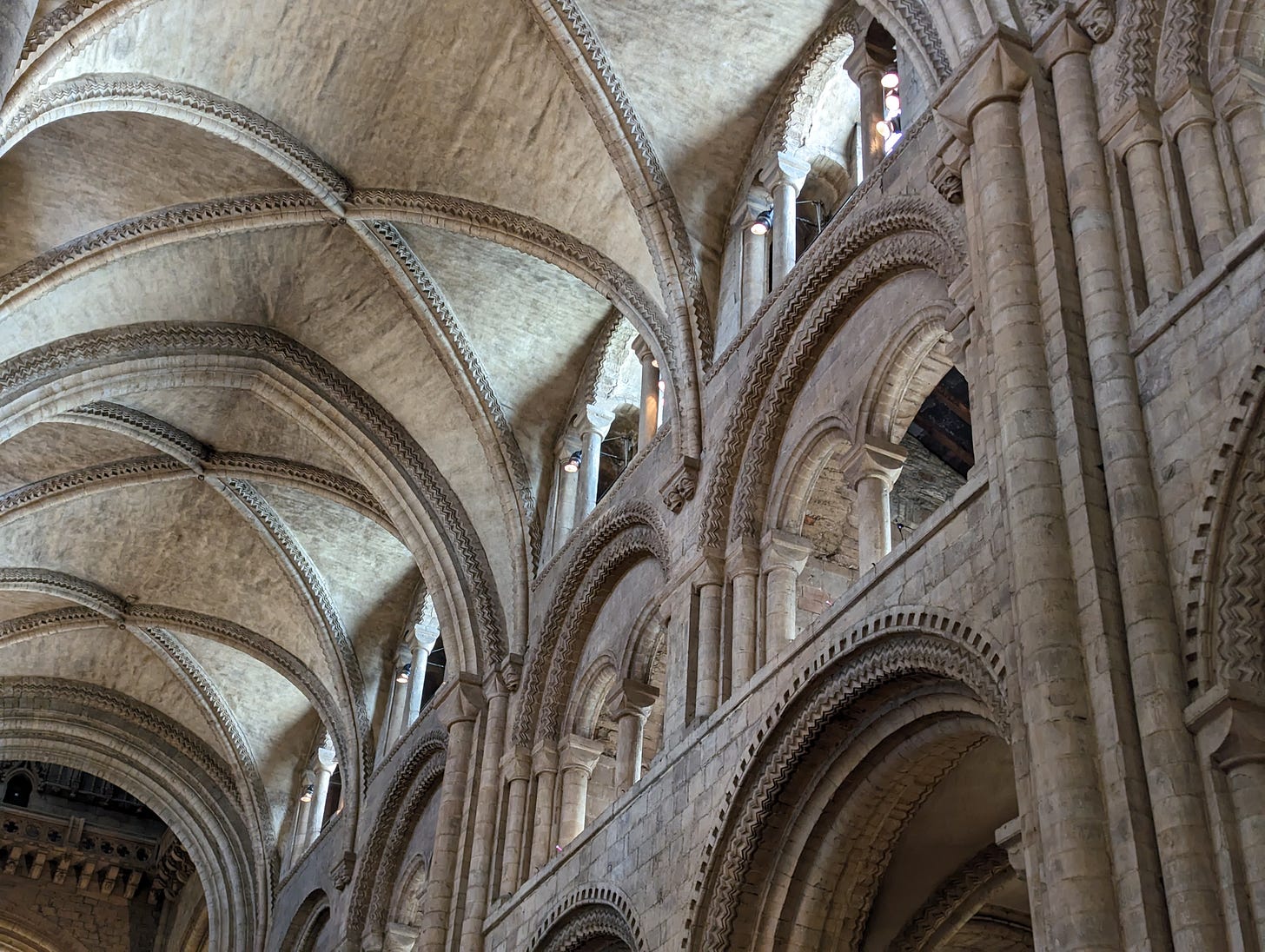

Durham is dominated by its Norman cathedral, high on a peninsula formed by a bend in the River Wear. Crossing the viaduct on the train coming into the city, the vision of it immediately strikes you; I may be biased, but no reasonable person could dispute that it is the most glorious sight on the east coast mainline. Going throughout the city, you get different vantage points upon this remarkable and imposing building. Its sandstone can capture the warmth and the shifting of the sunlight in mysterious and magical ways; one’s spirit can soar upon the sight.

For a short while, I was a tour guide in the Open Treasure exhibition in the monks’ dormitory in Durham Cathedral. Durham Cathedral holds a unique place in my affections. I cannot think of any other building that is more powerfully at place-making: as a landmark, as a sanctuary, as a site of pilgrimage, as the crystallization of the soul of a city, as the heart of the diocese, as the embodiment of the city’s history and people. It is impossible to imagine Durham without it.

[Susannah: Like I said.]

Across from the cathedral, on the other side of Palace Green, stands Durham Castle. Now University College and accommodation for university students, it was formerly the palace of the Prince Bishops of Durham. Before that it was a Norman castle. Durham’s ecclesiastical history is fascinating: the bishops of Durham used to function as rulers in the north, with the right to levy taxes, mint coins, and raise their own armies. Well into the 1800s, the bishop of Durham still had a private army.

During our stay, I took Susannah to see the castle for the first time. Highlights of the castle include a Norman chapel, containing the castle’s sallyport and what might be the first image of a mermaid in England, upon one of the capitals of its columns. Tunstall’s chapel is also impressive and contains amusing reminders of Bishop Tunstall’s shrewd navigation of the religious politics of the Reformation. [Susannah: A real life Vicar of Bray, but you do get the pathos of it: he was doing his very best.] The Great Hall of the Castle, used for formal meals for the students of the college, served as an inspiration for the dining hall of Hogwarts. [Susannah: Meaning that the dining hall scenes were filmed there.]

We also visited Cosin’s Library, one of the historic libraries in Palace Green Library, a glorious place that very few visitors to Palace Green see.

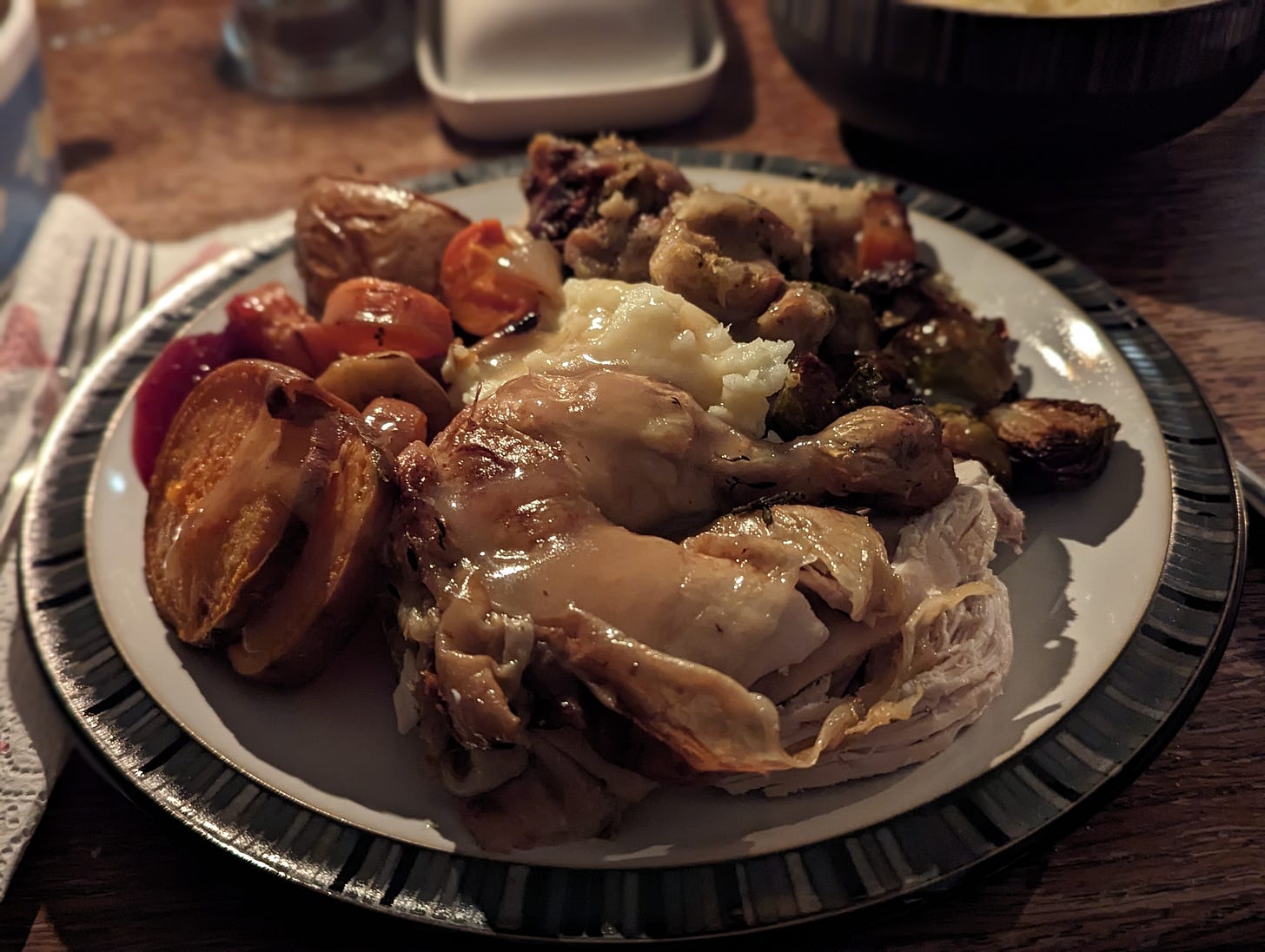

Our indulgent Canadian hosts also celebrated Thanksgiving with us on the Thursday. Susannah prepared a feast, with all the trappings.

[Susannah: Our hostess is gluten free and her son was going on a Scouts overnight after we left, so we ended up carrying most of the leftover pie, of which there was a good deal, away with us; we traveled to York and then to London, seeing friends along the way, and gradually giving away pie.]

Most of my favourite places have a distinctive natural topology, the lineaments of which are imaginatively explored and elevated by that which is built upon them, buildings typically distinguished by vernacular styles of architecture and local materials. Durham is such a place, a place whose buildings, thoroughfares, and lanes answer to, accentuate, and lovingly discover the properties of a location of peculiar natural beauty.

The prominence of the peninsula is made evident in the arresting grandeur of the cathedral upon its height, the river that gracefully embraces the centre of the city is crossed and framed by its medieval bridges and flanked by paths that invite visitors to accompany its waters on their gentle passage around Durham’s heart and out into the countryside that surrounds it, its varying and hilly terrain is ascended by graceful winding streets behind which lie a warren of lanes and paths that few use. Looking out over the city from one of the elevated vantage points in the surrounding countryside, the city can even seem as if it were situated within a great wood.

Bill Bryson wrote in Notes From a Small Island: Journey Through Britain:

I got off at Durham ... and fell in love with it instantly in a serious way. Why, it’s wonderful—a perfect little city ... If you have never been to Durham, go there at once. Take my car.

I entirely agree.

On Friday evening I had an hour and a half long online interview and discussion on the typological and symbolic reading of Scripture with a group of students in Cambridge, after which we travelled down to the city of York.

[Susannah: The thing about this country is that any random hall you are meeting in is prone to be roofed with Elizabethan oak timbering.]

On Saturday morning, we went to the presbytery meeting of the International Presbyterian Church, at which I delivered two forty-five-minute talks. After my talks we were privileged to be able to observe some of the proceedings of the presbytery, especially their examination of a minister for appointment in the presbytery. When seeing behind the scenes in ministerial contexts, it is wonderful to recognize the seriousness with which certain groups can take Christian ministry and the exacting standards to which they hold ministers and Christian teachers. This was such an occasion: both Susannah and I were very impressed. It was also wonderful to have some time to get to know some of those attending the presbytery afterwards in conversation.

[Susannah: I had of course met Presbyterians before, but this was clearly their natural habitat, a major part of their life cycle: this was a Presbytery of Presbyterians. They really came into their own. One thinks that Sir Richard Attenborough should make a documentary.]

While streets like the Shambles are clogged with tourists and Harry Potter fans, especially during the Christmas season, York is a glorious city. Its history goes back to the Romans, when it was a provincial capital called Eboracum. Constantine the Great was proclaimed as emperor while in the city. During the early Middle Ages, it produced Alcuin, b. 735, one of the most brilliant figures of the Carolingian Renaissance. It was later captured by the Vikings, who named it Jórvík. It continued to be a significant city after the Norman Conquest. After the brutal ‘Harrying of the North’, the castle was rebuilt and expanded and the cathedral that would in time become the current Minister was built. [Susannah: Read: William the Conqueror killed or drove out 75% of the population of the North of England after they refused to be bought off (except for the Danes, who weren’t local anyway,) and wouldn’t accept his overlordship. Northern men are basically still like this.]

We took full advantage of the hours that we had in York. Although we didn’t walk the city walls, we did get to visit the Treasurer’s House, which I had never seen in dozens of visits to the city. We also spent time in some of our favourite second-hand bookstores and at the Christmas Market.

Having heard that there would be a March against Anti-Semitism in London, both Susannah and I felt that it was important for us to participate; we travelled down from York on the Saturday evening. On Sunday morning we attended St James Clerkenwell, where we met up with two couples who are friends of ours. The last time I was at the church in early September, I delivered the sermon at the wedding of one of the couples.

The march gathered at the Royal Courts of Justice, where we met up with a friend who was also participating. The English weather also turned up, with a mild drizzle for much of the time.

I've never been on such a march before. The sort of emotions that can often animate protest marches—rage, bitterness, resentment, etc.—are emotions I keep on a very tight leash. The mood of this march, however, was very different.

Apart from occasional chants of “bring them home!”, it was a remarkably quiet affair. The animating spirit was one of deep concern for British Jews and for preserving British society’s hospitality, tolerance, openness, and peace more generally. Many of the participants were concerned to make clear that they weren’t marching against Palestinians, but for the place of Jews in British society.

I’ve never attended such a march before, but it felt extremely important to stand in solidarity with British Jews. There are many complicated things about the situation in Israel and Gaza. By contrast, the necessity of Britain remaining a good home for its Jews is a very straightforward issue.

As we were reminded in one of the speeches, how a society treats its Jews has historically proven to be a powerful test of its broader commitment to core civic and political virtues. In the current rise of anti-Semitism, British society more generally is failing this test.

Speakers from both sides of the political aisle spoke about the need to stand firm with British Jews. There was appropriate recognition of Israel’s right to take some action against Hamas (without justifying wholesale the form that its response has taken). It was heartening to witness the clear and strongly felt approval from the crowd of the sorrow the Chief Rabbi expressed for all lives lost in the conflict.

Over 100,000 people attended the march, the greatest number at an event against antisemitism since the Battle of Cable Street, the protest against Oswald Moseley’s British Union of Fascists, in 1936s.

[Susannah: I was conflicted about going to the march—I am deeply opposed to and appalled by the way that the IDF is carrying out the war, in violation of its own just war principles, and I didn’t want to lend my voice to those praising it. Indeed, most of the pro-Palestine marchers in London, at least, had been there in good faith in support of Palestine and in opposition to the IDF’s campaign against Gaza and the horrible deaths of civilians, but there had been far more real and overt antisemitism than I had ever expected to see in public as well—not just lack of support for Israel. And in any case I had been feeling strangely lonely for the presence of Jews since leaving New York. I knew what I meant by going, what I intended—but I was very concerned that I would find people there either denigrating Palestinians and celebrating their deaths, or using the occasion to be generally anti-Muslim or anti-immigrant.

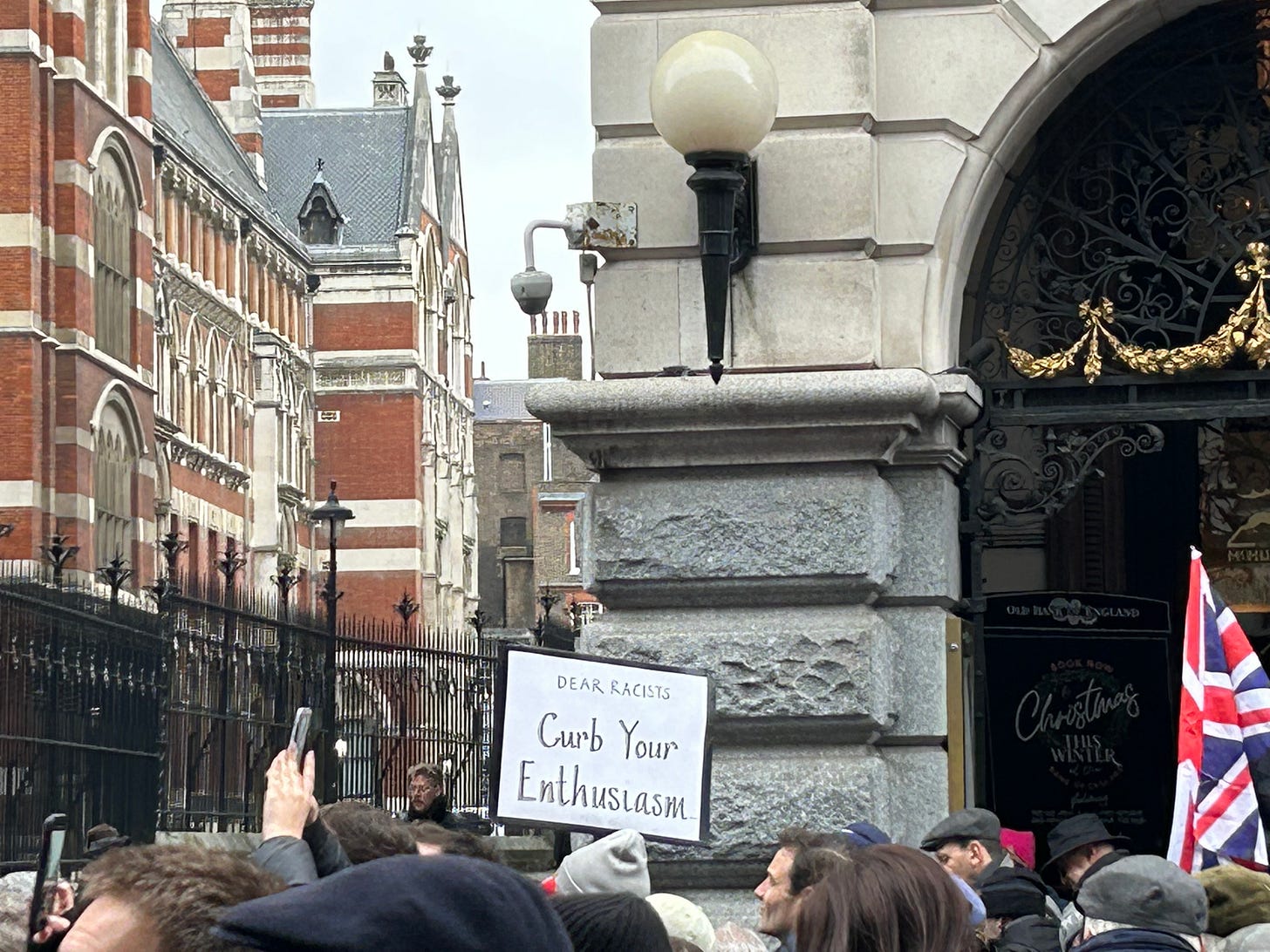

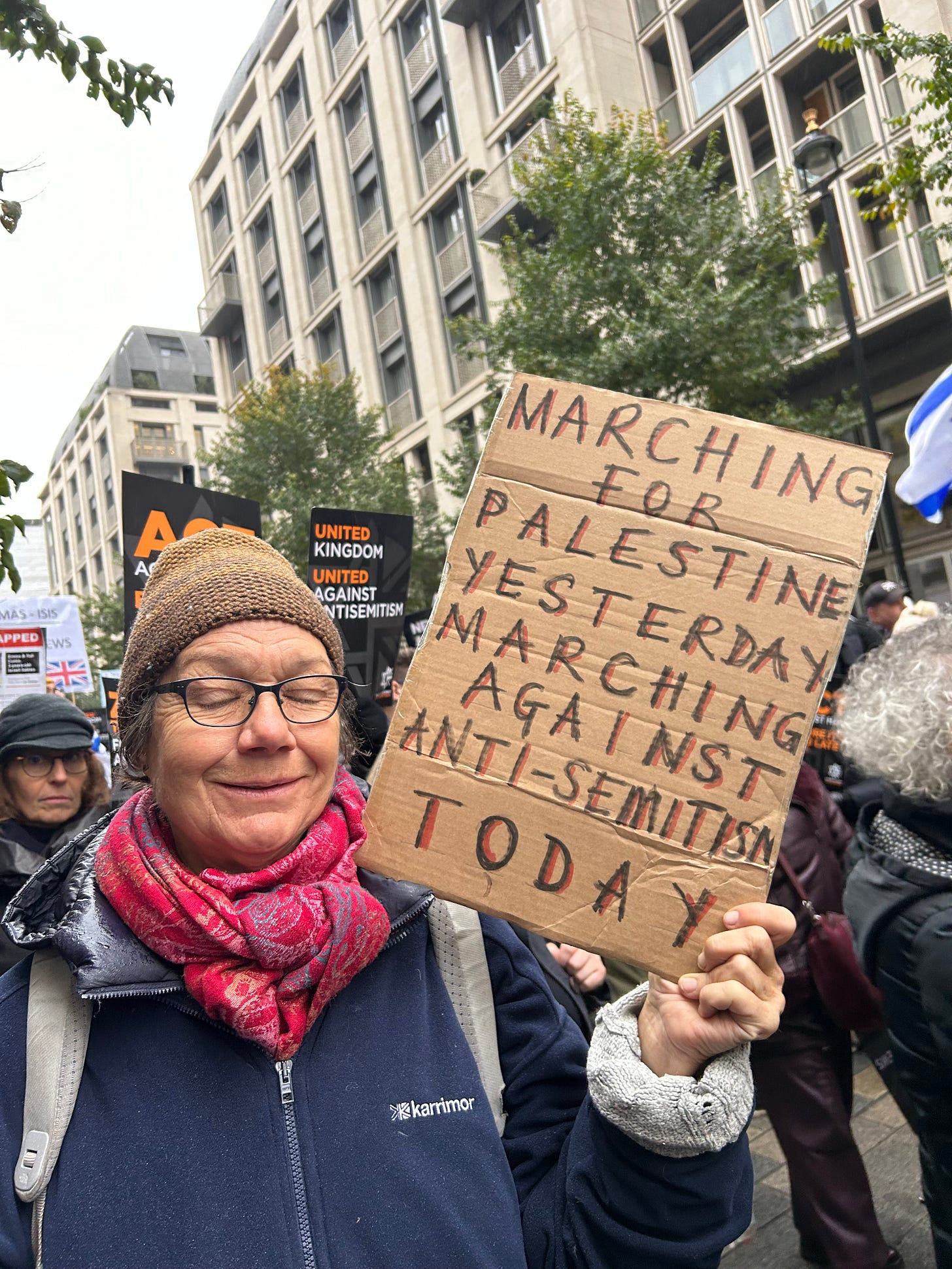

I was comforted by the fact that the day before, the organizers of the march had banned Tommy Robinson from attending—he’s a generally nasty far-right public figure of sorts, for those not up to date on UK politics, and he’d tweeted something about intending to show up, clearly intending to try to make the march “about” Islamophobia and his anti-immigrant agenda. He was told by both the march organizers and by basically every British Jew on twitter that he was not welcome. (He showed up anyway and, at the request of the organizers, was booted by the police, presumably on the grounds that he was likely to cause a disturbance.) This sign was among my favorites at the march.

I saw it at the same time another man marching; we caught each others’ eyes and smiled. In pure London cockney, he said “Best sign I’ve seen. Robinson doesn’t like Jews, ‘e just ‘ates brown people. Dick ‘ead.”

This was, however, the best sign I saw, and very much reflected the spirit of the march:

I was incredibly heartened that as far as I could tell, everyone there seemed to “mean” by being there something like I did—there was no anti-immigrant rhetoric, no anti-Palestinian rhetoric. As Alastair mentioned, the Chief Rabbi, who replaced Jonathan Sacks after his death several years ago, spoke movingly about the deaths of Gazans and the unacceptability of any civilian death. There was simply a firm refusal to allow antisemitism to go unremarked and accepted in public in England. It was an incredibly difficult needle to thread, but I think the organizers did well.

Following which, we headed back to Stoke.]

After all the events, travel, and speaking of that week, it was good to return to a more pedestrian and quotidian routine in Stoke. The last week has been packed with recording, teaching, and writing. I’ve written three articles, recorded several podcasts, had supervision sessions for several students, taught a couple of classes, prepared lecture notes and a syllabus for the beginning of 2024, and produced almost ten thousand words in correspondence, among various other things. I am feeling that I am in a regular rhythm of work again, something I’ve not enjoyed for a while now. On Thursday, I checked out of social media for the Advent and Christmas period (at least), which hasn’t hurt!

Yesterday we had a glorious frosty morning and last night we had a good snowfall. It is feeling like Advent in Stoke-on-Trent!

Running with Scissors

Several years ago, there was a Slate Star Codex post in which Scott Alexander coined the term ‘Scissor’ to describe statements, news stories, or ideas designed or selected for maximal controversy and divisiveness. The concept has since been adopted by others; Ross Douthat notably used it to describe the viral video of the Covington Catholic High School student Nicholas Sandmann, a perfect example of a scissor.

The concept of the ‘scissor’ is one I’ve found very illuminating and useful. It captures a dynamic, most potently operative on social media, whereby interpretative differences over specific statements, news stories, or ideas can escalate into the most heated and polarized oppositions, into antagonisms that far exceed anything seemingly justified by the stakes of the precipitating issue. Such ‘scissors’ can depend much less upon the intrinsic importance of the matters that occasion them than upon the supposed wrongheadedness of others in their response to them. Relatively low stakes ‘scissors’ can blow up into global arguments, fuelled by incredulity and anger at any who see things differently.

In many respects, ‘scissors’ are cases where people sense that fundamental differences in perception are surfacing. Back in 2015, there was a viral photograph of a dress, the colour of which was disputed by viewers: some saw it as white and gold, others as blue and black. While the colour of the dress was matter of no significance in itself, it revealed more fundamental differences of perception, and so a random photograph of a dress became a matter of global discussion.

While differing perceptions of colour are fascinating, they are relatively low stakes when compared to fundamentally different perceptions of social and political reality. The classic scissor appears to expose such differences and one’s interpretation of a scissor is a seeming ‘shibboleth’ by which people will pigeonhole you ideologically. Numerous examples of such ‘scissors’ could be given—Kyle Rittenhouse, Brett Kavanaugh, and ‘All Lives Matter’. People can get exceedingly animated about these matters, even if they seem to concern issues that, in and of themselves, are only of more local and limited importance. Someone with an opposing interpretation can seem alien, inexplicable, and threatening.

My sense is that the prominence and power of this dynamic cannot be understood apart from an appreciation of the way the Internet, and especially social media, has transformed our epistemological environment. It is difficult to grasp much about the ways that people currently think, express themselves, communicate, argue, and are persuaded without some appreciation of these radical transformations. However, few are clearsighted about what has occurred, the dynamics of the epistemological environment we now operate within, the way that it shapes us, and how we might avoid being unreflectively determined by its forces.

In a recent article for The New Atlantis, Jon Askonas, one person with a clearer appreciation of this, declares the passing of ‘the fact’ (ca. 1500-2000) and the central place that it enjoyed within our ways of knowing. Prior to the rise of the fact, Askonas argues, ‘knowing felt like fitting something—an observation, a concept, a precept—into a bigger design, and the better it fit and the more it resonated symbolically, the truer it felt.’ Particularly with the invention of the printing press, the means for the production and dissemination of ‘the fact’ had come and things such as modern science could arise. ‘Facts’ were plentiful but not superfluous, were guaranteed and produced by authoritative experts, and gave the impression of a sort of transcendent universality and objectivity: one could see a text such as the Encyclopaedia Brittanica as a symbol of this epistemological order.

The Internet, however, introduces an age of superabundant information, increasingly produced through automated processes and no longer controlled by dominant experts and authorities. Askonas quotes L.M. Sacasas: “super-abundance … encourages the view that truth isn’t real: Whatever view you want to validate, you’ll find facts to support it. All information is also now potentially disinformation.” Where ‘facts’ were once believed to be trustworthy grounds from which a meaningful, ordered, comprehensive, integrated, authorized, and compelling narrative would organically emerge, in the age of superabundant data this is no longer the case (Sacasas’ treatment of this is insightful). In place of ‘the fact’, the age of superabundant data prioritizes ‘stories’ or ‘narratives’ and those who create and disseminate them. Askonas writes:

But in a world of superabundant, readily recalled facts, generating the umpteenth fact rarely gets you much. More valuable is skill in rapidly re-aligning facts and assimilating new information into ever-changing stories. Professionals create value by generating, defending, and extending compelling pathways through the database of facts: media narratives, scientific theories, financial predictions, tax law interpretations, and so forth. The collapse of any particular narrative due to new information only marginally reshapes the database of all possible narratives.

The writers at Ribbonfarm have often reflected upon the importance of narrative processes of meaning-making, upon different forms of narratives, and the character of ‘narrative selection’. Our current environments, they argue, represent a significant transformation of modes of narrative formation, dissemination, and selection. For instance, Venkatesh Rao comments upon the role played by ‘vibes’ and ‘memes’ as a sort of ‘narrative ooze’ in our developing epistemological environments. Vibes and memes are, Rao suggests, akin to a ‘low-level code’, words that function, not at the high level of abstraction of a New Yorker article or TED talk, but which ‘trace the contours of flows of collective consciousness energy.’

Where data points are superabundant, narratives will tend to be weak and incoherent. The extreme messiness of reality and its seeming lack of meaning will dominate. However, as humans have a felt need for a meaningful—for a narratable—world, the meltdown of narrative in the age of superabundant information can be intolerable. Memes, vibes, and other such viral phenomena can appeal directly to our hunger for narratability, offering us master narrative frames within which to inhabit a messy world meaningfully and to hold its bewildering complexity at bay.

After the dethroning of the fact, such master narratives will increasingly determine our interpretation of specific data points—news stories, statements, ideas, or events. Indeed, ‘interpretation’ might not be the best word here, suggesting a conscious, reflective, deliberative, and temporally extended process through which an understanding is achieved. Narratives, however, tend to operate on a primal and less conscious level, the sort of level that vibes, memes, and other viral social phenomena tap into. People just immediately perceive reality as meaningful within a sort of tacit aesthetic frame, a frame that they neither understand nor can fully articulate.

And this is where ‘scissors’ come in. ‘Scissors’, it should be recognized, chiefly concern situations where interpretation is less straightforwardly demanded by ‘the facts’. The most prominent cases in racial justice arguments, for instance, tend to be, not the strongest and the clearest, but the most controversial, the scissor cases where contrasting underlying master narrative frames seem to come into view. The ‘ideal’ scissor case is one where two or more master narratives are directly competing for control over reality, with the ‘facts’ that they render being regarded as symbolic and revelatory of the larger narrative reality that they project.

Ideology holds considerable attraction in such a context of information superabundance. Ideology offers tidiness, a way of corralling the complicated data points into a grand narrative about the patriarchy, the tyranny of the left, late capitalism, whiteness, wokeness, or something else. Ultimately, reality can be boiled down to a fundamental opposition between good and evil, with specific cases being heads of one great Hydra lurking between the dark surface of the sea of reality, uniting them all. Ideology is extremely narratively compelling and its projection of clear meaning offers an intoxicating certainty to the action that responds to it. And for those within a narrative, it can be transparent—both in the sense that they don’t see the story as a story but simply see reality through that story, and in the sense of “transparently obvious:” how could those who disagree with me not see as I see? It must be that they do see, but are vicious.

COVID, of course, was a great example of the way that our new epistemological environments (don’t) work, and their contrast with older ones. Information was superabundant, bewildering complex to non-experts, and was generated from non-integrated domains. However, given the perceived existential urgency of the situation and the anxieties that we feel in the face of inscrutable and meaningless realities, agnosticism or radical uncertainty were not attractive options. An environment of superabundant information meant that the authorized ‘fact’ and the assurance offered by experts were no longer effective in securing certainty and consensus, even when underwritten by official authority and power. Consequently, different narratives competed to offer a comprehensive and compelling frame that answered to the existential needs. And, in the context of social media, these—even the officially ‘authorized’ narratives—routinely operated through the ‘narrative ooze’ of viral emotions, memes, and vibes.

Of course, as tends to be the case, the reality was exceedingly messy and all such narratives were greatly overplayed. Acknowledging the limits of narratability and the difficulty of finding coherence in an age of superabundance is an alternative to fights over ‘scissors’. Much of the power of scissors arises from our unwillingness to surrender data points to the fog of complexity and our desire for the compelling narratives offered by ideology.

The collapse of ‘the fact’ and the dominance of competing narratives has the social correlate of tribalism. The vibes, memes, and ideologies function through social virality, and the narratives are advanced and fought over by opposing parties. Postmodernism made us all more alert to the ways that ‘truth’ is generated by power, which power then employs to underwrite itself; in the post-fact era, suspicion can mutate into increasingly cynical and nihilistic forms. Narratives generate and strengthen solidarities, and narratives can develop in response to the interests of tribal groups. Strong narratives can form intense solidarities and internal doubting of aspects of tribal narratives can feel like a compromise of loyalty or even as betrayal.

Within this environment, ‘narratives’ can also be a lot less rational. Narratives on the right, for instance, increasingly respond to thumotic demands, and to the question of whether someone is a friend or enemy. The question of whether the ‘vibes’ of a position satisfy the gut—whether it feels sufficiently ‘based’ or masculine, for instance—can be much more determinative than those of supposedly objective ‘facts’ and reality. Persons who are native to such an epistemological environment can approach reality as a sort of gestalt and the solidarity of the tribalism corresponds to the unity of its narrative. It is very difficult to disaggregate, differentiate, and discretely handle specific aspects of such perceptions of reality. The whole is at stake in each part and challenges to any element will also be experienced as a challenge to the integrity of the tribe.

‘Scissors’ do not merely reveal the operation of different narrative frames, they advance and police them. Social media, with its vibes, memes, and viral elements, does not merely constitute a new epistemological realm that we must navigate, but is itself the operation of novel collective ways of knowing, ways of knowing that are no longer typically those of clearly differentiated agents engaging in responsible, defined, and temporally extended acts of deliberation and reflection.

The post-fact era of vibes, memes, and virally competing narratives is weird and disorienting. Thought, discourse, and persuasion no longer function in the ways they once did. If we do not seek to understand our processes of understanding and act to preserve or recover a healthier epistemological environment, we risk being much diminished in our rational agency and capacities. We risk too cutting ourselves off from other people not of our ideological tribe, becoming unable to see them in any capacity other than as the villains of our tribes’ stories. But this is not a sentence of doom, and risk is not certainty. Reality still exists: we must find a way to remain attuned to it, responding with sanity and grace to the complex world we have been given, remaining open to each other, not rejecting stories but not necessarily absolutizing every one that seems right.

Raising Isaac

In Hebrews 11:17-19 we read of Abraham:

By faith Abraham, when he was tested, offered up Isaac, and he who had received the promises was in the act of offering up his only son, of whom it was said, “Through Isaac shall your offspring be named.” He considered that God was able even to raise him from the dead, from which, figuratively speaking, he did receive him back.

Some commentators have wondered where the author of Hebrews might have gotten the idea Abraham would have considered the possibility of the Lord restoring Isaac to him by raising him from the dead. In verse 12 of the same chapter, the author of Hebrews highlights the analogy between such a resurrection and the manner of Isaac’s birth: “Therefore from one man, and him as good as dead, were born descendants as many as the stars of heaven and as many as the innumerable grains of sand by the seashore.”

Romans 4:16-19 explores the same association:

That is why it depends on faith, in order that the promise may rest on grace and be guaranteed to all his offspring—not only to the adherent of the law but also to the one who shares the faith of Abraham, who is the father of us all, as it is written, “I have made you the father of many nations”—in the presence of the God in whom he believed, who gives life to the dead and calls into existence the things that do not exist. In hope he believed against hope, that he should become the father of many nations, as he had been told, “So shall your offspring be.” He did not weaken in faith when he considered his own body, which was as good as dead (since he was about a hundred years old), or when he considered the barrenness of Sarah's womb.

The reading of the story of the Binding of Isaac in Hebrews 11 develops a line of interpretation that we find elsewhere in the New Testament, one which provocatively suggests, among other things, that Abraham was confident in the resurrection and trusted in a God that raises the dead.

Now, I think that we could overread the Old Testament text along these lines, treating faith in the resurrection as if it were explicit in texts where it is only implicitly, even if really, present. Nevertheless, I don’t think that the New Testament authors are just imposing some desired sense upon the Old Testament in these statements. They are concerned to read with the grain of the texts.

An important associated text is 2 Kings 4:8-37—the story of the Shunammite woman and the raising of her son. Throughout that story, there are several allusions back to Genesis 18 and 22, allusions which invite us to read the two stories in juxtaposition.

In 2 Kings 4, the Shunammite is given a miraculous child of promise. She stands in the doorway (verse 15; cf. Genesis 18:10) and the Lord’s messenger declares that she will have a son that time next year using the same expression as in Genesis (verses 16-17; cf. Genesis 18:10).

However, there is an unpleasant twist to the Shunammite’s tale. While with his father, the child of promise falls ill and later dies. He is placed, not on an altar on a mountain, but on the prophet’s bed in a rooftop room. His mother then takes a donkey, as Abraham once did. She travels to the mountain, where she challenges the prophet concerning the loss of her promised child.

The wood—Elisha’s staff—is placed on the child by Elisha’s servant, but the child doesn’t stir. Like Abraham left his servants and went up the mountain with Isaac alone, Elisha removed all the others, leaving only him and the lad. He laid himself upon the body of the dead child once, and then again, and the child was raised.

The story of the Shunammite woman and her son is a story recalling Genesis 22. It might answer the question in the back of our mind: what about Sarah? What would have happened if Abraham had returned without Isaac? What recourse might Sarah have had? The Shunammite woman is like Sarah seeking the return of her dead promised child.

This passage also gives surprising support to Hebrews 11:19. Already in the intra-canonical reflection of the Old Testament, the possibility of an appeal to God for the resurrection of a sacrificed Isaac has been raised.

Recent Work

Alastair

❧ Our latest Mere Fidelity episodes were on Reforming Criminal Justice with Matthew Martens.

❧ The Theopolis Podcast’s series on Deuteronomy continues with episodes on Deuteronomy 20: War and the City and Deuteronomy 21: Atonement for Unsolved Murders.

❧ My series on the book of Revelation with the God’s Story Podcast continues with an episode on the beginning of the seven bowls in Revelation 15.

❧ My friend Rev Uriesou Brito invited me on his Perspectivalist podcast for a discussion of discussion of How the Grinch Stole Advent.

Upcoming Events

❧ The third UK Davenant Convivium will be on the 24th January, with Oliver O’Donovan as the keynote speaker.

❧ Alastair’s Hilary Term Davenant Hall course, starting in early January, will be on ‘The Bible and Politics’:

The words and teachings of the Bible are frequently deployed and appealed to in our political discourses. Yet such engagement with the Bible is typically superficial and merely rhetorical; while the Bible affords shallow prooftexts and resonant turns of phrase, it is seldom serving as a deep and guiding source of wisdom in our political thinking. In recent decades, after a long period of neglect, the importance of the Bible’s influence in historic political reflection has received growing attention. In addition to considering such retrievals of the Bible’s significance as a political text for historic thinkers, this course will seek to discover more of the Bible’s enduring insight and generative potential for political reflection. We will investigate some of the variegated ways that the Bible encourages, serves, and directs our political reflection and consider how we can engage with its voice most responsibly and profitably.

You can register for the course here.

❧ Most of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Susannah and Alastair

Looks magical.

The demeanor of the crowd at the March against Anti-Semitism seems to lend some hope that the post-fact era hasn't overwhelmed everyone's abilities at nuanced discernment.