№ 32: Intellectual Salons and a New Goddaughter

Also why you probably ought not steal your brother's blessing and why John's gospel has a perfect ending

Dear friends,

Susannah: We’re back in NYC, for a good solid chunk of time, and lemme tell you, I do not mind that even a little bit. We spent Easter weekend up in Boston, in a wonderful extremely Anglo-Catholic Episcopalian church called Church of the Advent, because my friends had asked me to be their baby daughter’s godmother. Baby was successfully baptized, we celebrated, and we’ve spent the two weeks since Easter working hard, taking walks in Central Park, and enjoying time with long-neglected NYC friends.

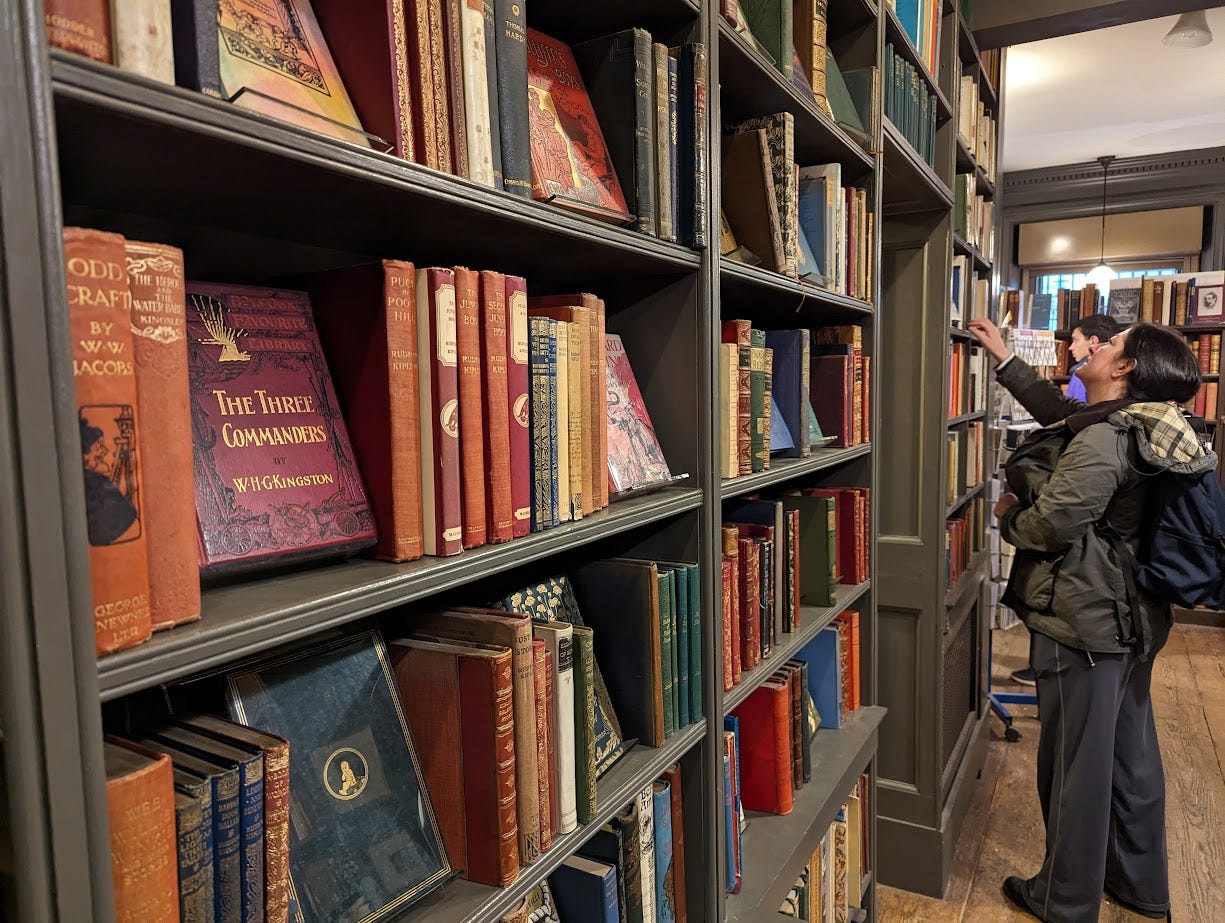

I’ve also done two talks, both for Interintellect, a wonderful new organization that I feel I am getting wonderfully embroiled with. It’s basically a series of salons, in person and on Zoom, on a huge variety of topics; they haven’t hitherto been very focused on religion, but Anna Gat, who’s the head of the org, is wanting to bring more religious angles into these conversations, and I am VERY up for this.

The first salon, I actually was the moderator at: it was a conversation about faith and progress, with a panel consisting of two Episcopalians, a Mormon, and a Muslim (we were basically all there because it was the Mormon’s—my friend Zach’s—birthday, and he had wanted a panel discussion for his birthday. That was a fascinating conversation; Matt Sitman, another friend, saw who was on the panel and asked “is anyone on that panel going to say anything good about progress?” But we did! Somewhat!

Mark Lilla, legendary academic and grand old man of “let’s not be too hard on liberalism” studies, was in the audience, and he was wonderful (though I disagreed with him)—basically making the case that Karl Barth’s approach to eschatology was the only sane one, that any attempt to bring the Kingdom of God on earth in a meliorist sense is either going to lead to authoritarian right or authoritarian left politics.

I disagreed because, while I am extremely worried about authoritarianism of both left and right, and while it gets even uglier when it has the self-righteousness of a nastily nationalist Christianity behind it, a) I don’t think that all political Christianity is necessarily authoritarian or tyrannical—the UK is a Christian monarchy and seems to be fairly non-tyrannical, and welcoming to people of all faiths and none—and b) I don’t think that state action is the only way that the Gospel transforms cultures and c) I actually do think it is a good idea to, in a kind of chill way, make your world a better place, or try to.

Christianity had transformed Roman culture a good deal before Constantine legalized it; so many of our basic assumptions (the infinite value and dignity of each human person, the idea that all men and women are in reality brothers and sisters and belong to one human family, the idea that forced marriage is wrong, the idea that slave-taking is shameful and evil, the idea that faith and religious adherence cannot and should not be coerced) are downstream of Christianity, though Christianity has of course fallen down on its own principles on many, many occasions. (And though of course there were inklings of these ideas in Greek and Roman culture as well, and in many other cultures; these ideas are part of human nature just as much as being horrible to each other is.)

Tom Holland’s incredible book Dominion is probably the most readable account of all this, and makes a very strong case for the cultural uniqueness and benefits of Christianity for what we now think of as good sensible decent respect for human rights; if you somehow haven’t yet read it, you must, also, he and his friend Dominic Sandbrook have possibly the best history podcast going.

CS Lewis’ Abolition of Man, though, is an important counterpoint: he makes an equally forceful case for the universal human testimony to many aspects of ethics: there is a common human moral law which seems to be written in every culture; though we never really keep it entirely and though different cultures opportunistically suppress different aspects of it, there’s a recognizable shape of the good life, the good society, the good family, the good friend, that we all seem to be drawn to.

Anyway that’s a long digression, everybody just go read both of those books, and here’s Mark Lilla’s big one. He ended up getting into a very intense back and forth with another guy who was there - whose name I didn’t catch - who had the vibe of having been recently teleported from Silicon Valley and who was making a strong techno-optimist case, claiming that religious people needed to make a better pitch than transhumanists if they want to outbid transhumanists in the Marketplace of Ideas; everything about this makes my skin crawl, but it was very fun watching him and Lilla go at it happily.

This is what Interintellect does: people who actually disagree have actual conversations. It’s marvelous. Also you should be aware of the substantial numbers of Mormon transhumanists out there. They may yet rule us all.

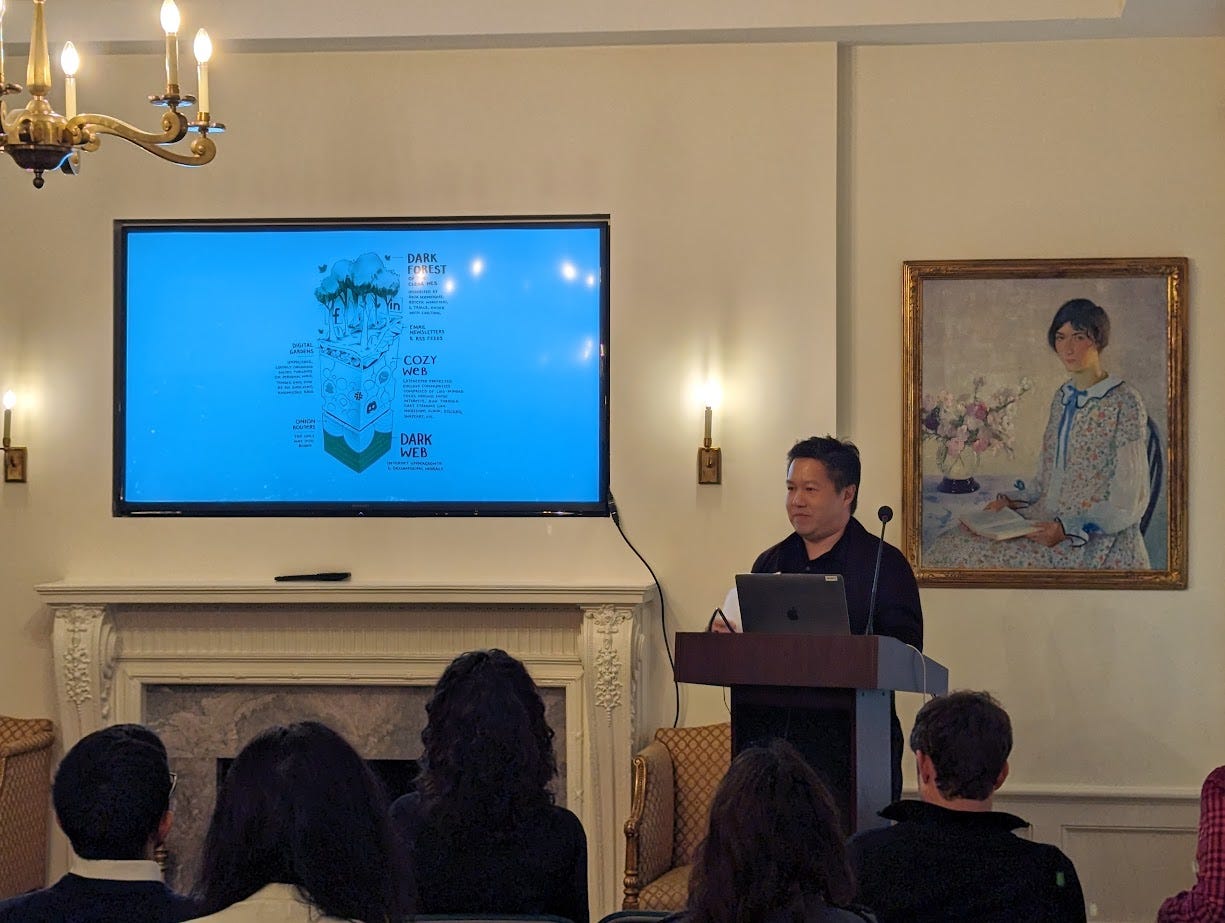

The second event I did—on Saturday—was a fifteen minute talk on Christian Humanist Journalism in the Age of ChatGPT, which I wrote in a frenzy in the Le Pain Quotidien on Madison and 79th in the hour before the event and which I delivered at breakneck speed because our panel had gotten a late start and the person who was moderating made hand gestures to tell me I had to deliver it in ten minutes. It’s good! I think. I’ll probably end up rewriting it and publishing it and when I do I will link here.

ALMOST TOTALLY UNRELATED: I was reading Measure for Measure the other night and I started thinking about how completely goofy Shakespeare is because other than Denmark and Scotland, he basically only understands two kinds of polities, which are “England,” and “Foreign,” and all foreign polities are Italian city states without fail.

SHAKESPEARE: my new play is set in a city state ruled by a duke and the characters are named “Angelo” and “Vincentio” and “Isabella” etc.

SHAKESPEARE’S FRIEND: ok so like Venice?

SHAKESPEARE: no haha Vienna

***

SHAKESPEARE (a little later): ok so I have a new play

SHAKESPEARE’S FRIEND: what’s this one about

SHAKESPEARE: ok so it’s set in a city state ruled by a Duke and the characters are named Orsino and Malvolio and Olivia and Viola and Antonio

SHAKESPEARE’S FRIEND: so it’s set in…

SHAKESPEARE: Yugoslavia, yes

Alastair: It has been another full few weeks since we last posted here! The following are some of the highlights.

I preached in our church in Stoke-on-Trent for Palm Sunday. We also went on a cycle ride along the canal, enjoying an afternoon tea at World of Wedgwood.

We had my parents around for a meal.

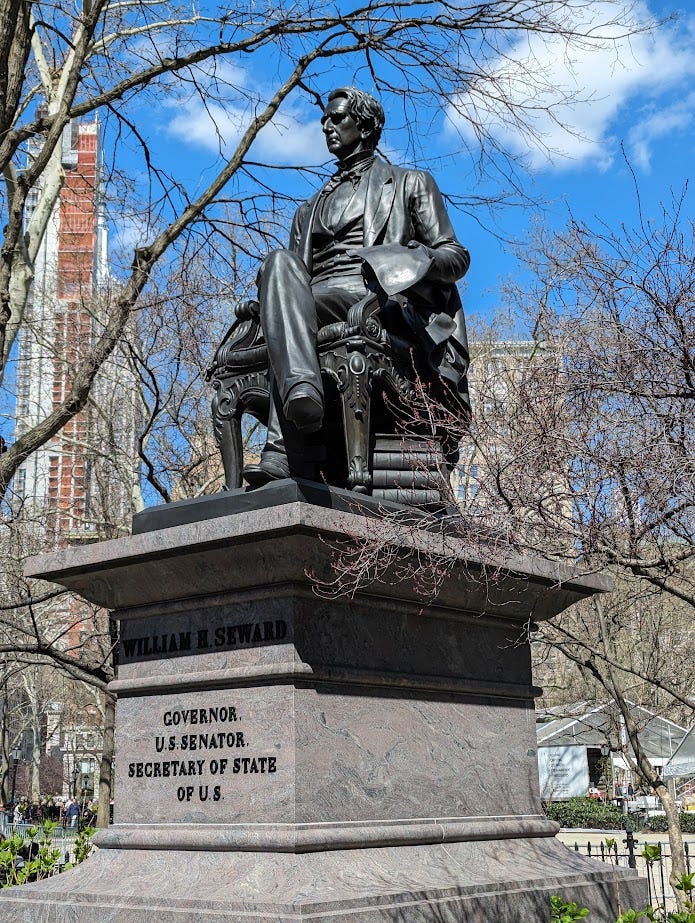

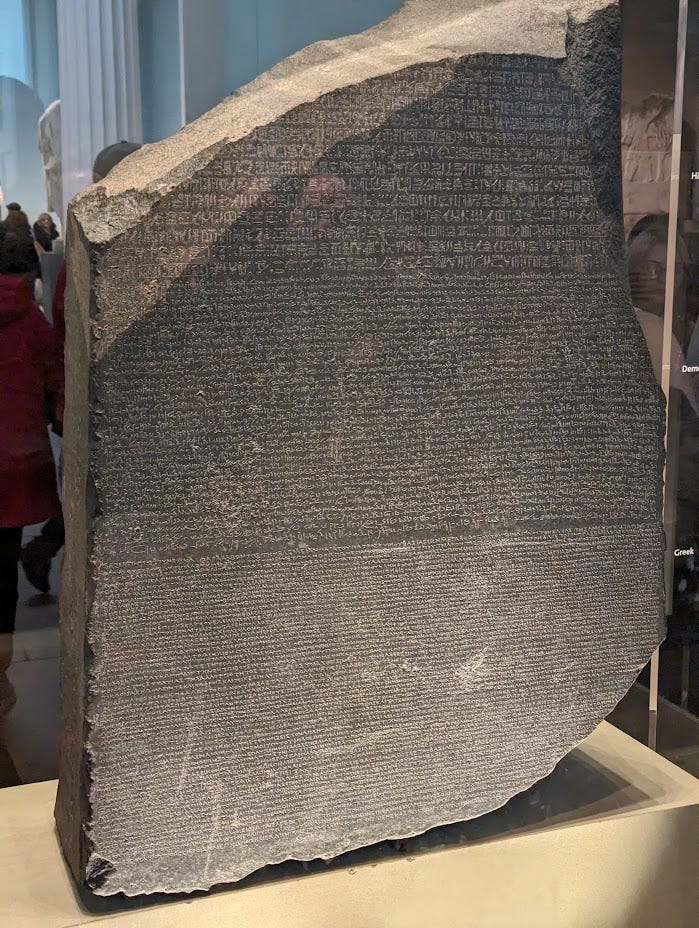

We travelled down to London, where we visited the British Museum again. While I was wandering around, looking for Susannah, a man walked directly at me and would not change his course, even when I tried to move to one side. It turned out to be Ben Virgo of Christian Heritage London (Ben interviewed me a few years back). Ben leads tour groups through the Museum, telling them about the biblical history behind some significant artefacts.

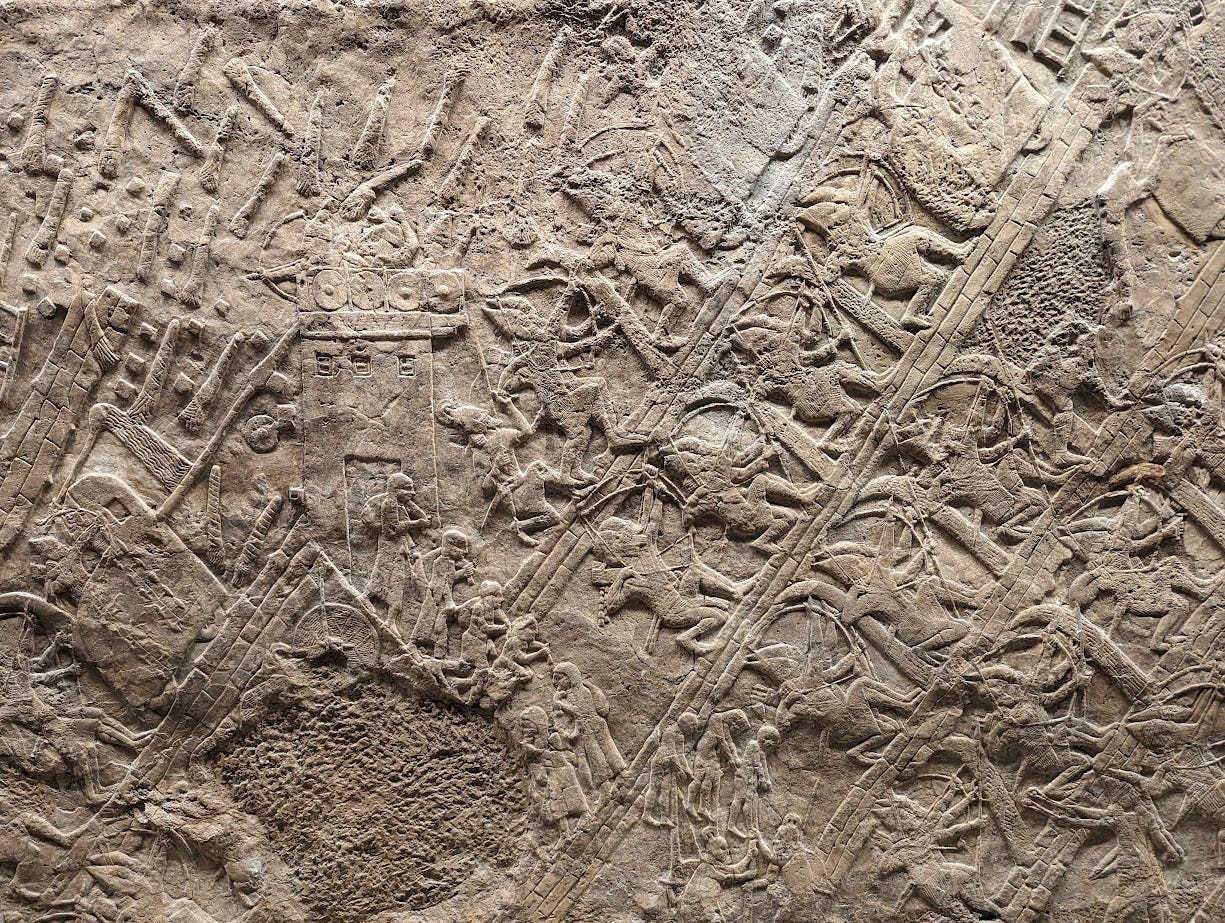

We joined his tour group, which we thoroughly enjoyed. He is doing superb work and I hope other people follow his example elsewhere. His treatment of the relief of Sennacherib’s capture of Lachish was perhaps the highlight for me (background for the events of Isaiah 36 and 37). 1

We also got to see the Rosetta Stone, Cyrus’s Cylinder, and some other incredible objects. We stayed that night in a Christian community house, enjoying the opportunity to get to know some of its members better.

On Wednesday, March 27th we flew back to New York City. We had a long walk through the city on Good Friday and enjoyed a meal with Susannah’s dad in the evening.

On the Saturday morning we took the train up to Boston for the baptism of Susannah’s new goddaughter (and god-granddaughter—she is the godmother of the child’s father too!).

We celebrated Easter at the Church of the Advent in Boston: Susannah’s goddaughter was baptized in the vigil on the Saturday and we were also there on Sunday morning.

It has been several years since I was last in Boston and it was a delight to see the place again. We took the bus back on the Easter Sunday evening, arriving home in the wee hours.

The next day we were visited by several Davenant friends and enjoyed a morning and afternoon in the Met Museum.

On Friday we were visited by another former Davenant friend (being in New York City, we have the benefit of many friends and acquaintances passing through—do tell us if you ever visit!).

On Saturday, April 6th, we attended a wedding in the city. Truly, so many of our friends are getting married off—it is wonderful!

It was a delight to be back in our New York church home on Sunday. Before the service, we met up with an online acquaintance and talked about an incredibly exciting church building project he is working on—it does not take much to get me going on the subject of the significance of church buildings and church architecture! After the service we enjoyed a meal with some church friends.

Monday was the day of the eclipse. We were busy, so we could not go upstate to witness the full eclipse. However, we did take a half hour to go to the park and people-watch, which was probably far more interesting than the (very partial) eclipse here in New York City.

On Wednesday, I started teaching my new course on Male and Female in Modernity for Davenant Hall. Once again, I am impressed by the calibre of the students in my courses.

The city is beautiful right now, with the apple and cherry blossom. We have had several long walks in the park and around the city after and between our work, which has been very busy.

On Friday evening, we had a meeting about a potential new Christian study centre in New York City, another exciting development we look forward to being involved in.

Susannah’s second Interintellect event was on Saturday.

Relitigating the Deception of Isaac

Of the stories of the Old Testament, one to which I have most often returned is that of Genesis 27: the story of Isaac’s blessing of Jacob. Reading Scripture intertextually, one routinely finds its stories shedding light upon facets of others. For readers of Scripture alert to such intertextuality, this frequently results in striking, and hence confirmatory, convergences in interpretation. However, in the case of Genesis 27, some of the readers of Scripture whose attentiveness and insight I most admire markedly diverge in their understandings of the passage.

In our previous Substack post, I addressed the question of why Mordecai refused to bow to Haman, another story upon which readers of Scripture who have influenced me differ considerably. Like the story of Mordecai’s refusal to bow to Haman, the story of the deception of Isaac is one upon which the interpretation of much else hangs. While our understanding of Mordecai’s actions will colour our reading of much of the rest of the book of Esther, the deception of Isaac is a pivotal event in the first and foundational book of the Bible and our divergences at such a point will likely prove even more consequential.

It has been wonderful to be back in our church in Manhattan, having not been there since January. We are working through the book of Genesis and, as we are currently considering the story of Jacob, it led me to revisit the question of how to understand the episode. I thought I would take this occasion to discuss some of the proposed readings of it, and some of the considerations that might shape an intertextual reading of the passage. Puzzling through the reasons for their divergences might help us better to perceive, not only key questions of interpretation for Genesis 27, but also matters of interpretative principle more broadly.

James Jordan, the first of the three commentators I will consider, treats the story of the deception of Isaac in places such as his book Primeval Saints: Studies in the Patriarchs of Genesis and in his series of talks on the life of Jacob. There are several features of the story to which Jordan directs our attention as interpreters, features that control his own reading. Perhaps the most important of these features relate to the initial explicit characterization of the chief actors within the story.

Jacob, Jordan argues, is first introduced to us as a ‘complete’ or ‘blameless’ man (25:27). While most translations use terms such as ‘plain’, ‘peaceful’, or ‘quiet’ to translate the term in question (תָּם), Jordan insists that this is ducking the most likely force of the term, the same term that is used to characterize Job in Job 1:1. Because they have already Jacob to be a bad guy, they shrink back from the most reasonable translation of the text.

Besides this positive characterization of Jacob, we have the very negative characterization of his brother Esau. In 25:34, Esau is described as having despised his birthright. Further, in 26:34-35, we are told of Esau’s choice of Canaanite wives for himself, greatly distressing his parents. Esau seems to be wholly unsuited to be the heir of the covenant, yet, despite his unsuitability, Isaac his father favours him and has determined to bestow a great blessing upon him, making him lord over his brethren. In 25:28 we are informed that Isaac favoured Esau as, literally rendered, Esau’s ‘hunting was in his mouth.’

Considering also that the Lord had revealed to Rebekah that the older child in her womb should serve the younger (25:23), Isaac’s favouring of Esau over his brother (not to mention that he favours him as a servant of his appetite for game) seems utterly inappropriate. Indeed, Isaac seems to be prepared to jeopardize the covenant for the sake of his appetite. He plays God in favouring Esau on account of his game, over the son whom God had indicated should be blessed. Isaac’s senses are failing him as he loses his sight and, notably, he allows the lower senses of taste, touch, and smell to override his ears’ warning that the voice of the son is that of Jacob, not Esau (27:22).

In Scripture there are recurring themes of women deceiving and outwitting ‘serpent’ figures, who oppose and/or prey upon the righteous seed. The serpent deceived the woman in the Garden, and now the serpent is repaid in kind as his seed are deceived by the daughters of Eve. Rebekah, Jordan argues, stands in the line of such women, acting courageously as other women such as Rachel, the Hebrew midwives, Rahab, Jael, Michal, and Esther will do later in the scriptural history. Rebekah’s deception of her husband, Isaac, rescues him from the great sin that he is about to commit and ensures that the righteous son is blessed. Isaac’s response to the deception is an indication, Jordan believes, that he recognized that he had not been in the right.

Jordan definitely highlights important aspects of the text here, aspects that could be filled out further. For instance, we might notice unflattering resemblances between Isaac and the son that he sinfully favours. At the end of chapter 25, Esau, claiming that he was about to die, despised his birthright for some of Jacob’s stew. A curious feature of Isaac’s blessing in Genesis 27 is that it was occasioned by Isaac’s belief that he was on the brink of death. In fact, Isaac would live for about fifty years more. Like Esau, driven by animal appetite, Isaac acts precipitously, unilaterally (Rebekah only found out because she overheard the conversation between Isaac and Esau), and recklessly.

Jordan’s reading might also be strengthened by consideration of the providential factor involved in Rebekah overhearing Isaac’s instruction to Esau. Furthermore, the Lord declares his promise to Jacob at Bethel in the chapter that follows and blesses him in the house of Laban. This would be surprising if Jacob were indeed acting viciously throughout.

It seems to me that Jordan’s claim that an unwarranted yet determined prejudice against the character of Jacob has settled the meaning of the term תָּם for many commentators does not sufficiently reckon with some of the considerations informing such a reading. Not least among these considerations is the implied character of Jacob in the deception of Isaac. It is not without some questionable interpretative moves and moral claims that Jacob can be regarded as upright and justified in his deception of his blind father. On the surface of things, Jacob’s deception of his father, whether he was the rightful recipient of the blessing or not, appears to be sinful. Allowing such a judgment to colour our reading of the earlier term and to suggest that it ought to be understood in a less common sense is not simply unreasonable, much as Jordan’s use of his interpretation of the earlier term to suggest a less common reading of chapter 27 is not simply unreasonable either. They are both debatable judgment calls and both arguably require departures from the most natural reading of the text at key points.

Besides this, we should observe the way that, in the text’s characterization of Jacob, he seems to be juxtaposed with his brother Esau.

When the boys grew up, Esau was a skillful hunter, a man of the field, while Jacob was a תָּם man, dwelling in tents.

There is a contrast between their respective realms of habitation: Esau is a man of the field while Jacob is a man dwelling in tents (perhaps reminiscent of the contrast between Cain and Abel). If we read the characterization of Jacob as תָּם as juxtaposed with the characterization of Esau as a ‘skillful hunter’, the sense ‘blameless’ or ‘perfect’ would seem to unbalance the juxtaposition. A more balanced juxtaposition would be given by a sense such as ‘peaceful’ (see the parallel between תָּם and ‘man of peace’ in a place like Psalm 37:37). The broader contrast, then, would be between Esau, a violent, impulsive, rough, aggressive, ruddy and hairy hunter chiefly operating in the wild, and Jacob a peaceful and more domestic man, smooth of skin, and quiet of temperament. Esau, the stereotypically masculine of the two, is favoured by their father, Isaac, while Jacob is favoured by their mother, Rebekah.

I’ve previously written about Yoram Hazony’s treatment of this passage, comparing his approach with Jordan’s. Hazony brings aspects of the text into view that are not really addressed in Jordan’s approach. Hazony claims that there are typically moral judgments upon such incidents to be discovered within the biblical text itself, if only we are attentive to the wider scope of the Scripture and acknowledge a few illuminating guiding principles, including the following:

First, characters are juxtaposed and contrasted in narratives in ways that imply judgments upon their actions.

Second, patterns of events are repeated in ways that highlight the character and consequences of past actions.

Third, key recurring expressions alert attentive readers to specific connotations or connections.

As we attend to such principles, we can arrive at far more sophisticated judgments upon events and actions. Hazony writes of the story of Jacob’s deception of Isaac:

I don’t think … that there is much question that the narrative portrays Jacob’s having deceived Isaac as a significant moral failing. In a sense, Jacob’s entire life is described as being lived in the shadow of this one terrible mistake he made as a young man. And yet the narrative is equally insistent that Jacob was right to resist Isaac’s wish that Esau, the firstborn, be his heir. The very name “Israel,” which God gives Jacob, is said to mean “you have contended with God and with men and have prevailed”—reflecting the pleasure that God takes, not in Jacob’s execrable deception, but in the fact that Jacob has resisted the fate his birth as the second twin had decreed for him. This means that as the story unfolds, Jacob is punished for the way he treated his father and brother, even as the narrative reconfirms that his motives were the right ones, and even shows respect for his willingness to act on these motives. [The Philosophy of Hebrew Scripture, 82]

In arriving at this assessment, Hazony deploys a principle that is much less pronounced in Jordan’s thinking on Genesis 27. Jacob’s life was largely one of suffering, yet it is dominated by two key deceptions that he suffered at the hands of others. The first of these deceptions occurred in the darkness of Jacob’s wedding night, when his father-in-law Laban deceived Jacob, giving him his weak-eyed older daughter in place of Rachel, the beautiful younger daughter for whom Jacob had served. This deception is too reminiscent of Jacob’s deception of his father, Isaac, to seem accidental. It seems reasonable to regard the misery that this deception brought to Jacob as a providential judgment upon Jacob’s own deception of his father.

Jacob had deceived his father using goats (to make the stew and cover his smooth skin) and a coat (the best garments of Esau). Jacob’s deception is recalled in the second great tragedy that dominated his life: the apparent death of his favoured son, Joseph. In Genesis 37:31-33, Joseph’s brothers used Joseph’s special robe and the blood of a goat to deceive their father concerning his son, and to prevent Jacob from giving the blessing to their younger brother. That Jacob’s actions seemingly come back upon his head in such terrible ways suggests that his actions were in fact sinful, undermining one aspect of Jordan’s interpretation. Nevertheless, as I believe we shall see, Jordan’s reading need not be entirely jettisoned.

Here we arrive at the third interpreter whose insights into the passage I want to consider: Rabbi David Fohrman. Fohrman helps our reading in part by expanding the range of potential allusions and connections to which we are attending, arguing that we might hear some echoes of the story of the binding of Isaac in chapter 22. In that story, as in chapter 27, there are significant words exchanged between a father and son—‘My father’ and ‘here I am’ (22:7). In chapter 27, both Isaac’s exchanges with Esau (verse 1) and with Jacob (verse 18) recall this conversation he once had with his own father, Abraham. In that story too, it had seemed that Isaac was near to death and its events had led to a blessing.

It is not always clear what we should make of such apparent connections. This is not an observation that Fohrman makes, but perhaps the details recalling chapter 22 might invite us to contrast Abraham and Isaac. Abraham is prepared to sacrifice his beloved son and the heir of the covenant, Isaac, obeying and trusting the Lord. However, Isaac so favours Esau that he is not prepared to give him up, even when he knows that Jacob is the one whom the Lord wants to receive the blessing.

Fohrman’s fuller treatment of the episode is found in two video series: Isaac & Rebecca: Would You Steal A Birthright From Your Blind Husband? and Jacob: Man of Truth?. Within these series, Fohrman presents a daring and surprising reading of the events of chapter 27, paying more attention to the actions of Rebekah. He observes that Rebekah had received a prophecy that Jacob was to be the blessed son (25:21-23). She loved Jacob from his birth, but Isaac had favoured Esau and gave Jacob an unflattering name.

Rebekah overheard Isaac and realized that he was about to bless Esau, but that he intended to give no blessing to Jacob. Indeed, when we read Isaac’s blessing in verses 27-29 and his words to Esau in verses 34-40, it becomes apparent that the blessing intended for Esau seemingly implied a curse upon Jacob. When Rebekah overheard Isaac’s instructions to Esau and realized his intent to bless Esau to the exclusion of Jacob, Rebekah sprang into action on Jacob’s behalf. However, Fohrman, following an interpretative principle that he frequently applies very fruitfully, encourages us to read the story without having the end in mind. Rather, at each stage of the story, we should be alert to the way that someone only knowing the details to that point would presume that things would play out.

Reading the passage with this principle in mind, Fohrman suggests that we stop reading at the end of verse 10 and ask ourselves what we think is taking place. Does it sound like she is planning a deception? Fohrman makes a case that she is not. Rebekah, Fohrman argues, aimed to win some blessing for her beloved son, Jacob, sending him into his father to make a case for himself.

None of the ingredients of a successful deception of Isaac seem to be present at this point. By all appearances, if this were a plan to deceive Isaac, it would be beyond hope of success, a hare-brained scheme doomed to catastrophic failure. Jacob’s voice is readily distinguished from that of his brother. He is bringing a meal of goat meat, rather than the game that Isaac delights in. To make matters worse, he would be trying to deceive his own father that he is his brother. There would be no margin for error whatsoever. What hope of success would such a plan have?

What about Jacob’s protest in verses 11 and 12, does it not suggest that some deception is intended?

But Jacob said to Rebekah his mother, “Behold, my brother Esau is a hairy man, and I am a smooth man. Perhaps my father will feel me, and I shall seem to be mocking him and bring a curse upon myself and not a blessing.”

Fohrman argues that it does not. Nothing has been said about Jacob pretending to be Esau, or that Jacob should take Esau’s blessing by deception. The plan is rather that Jacob should seek a blessing from his father for himself before it is too late, lest he be left with nothing. Why then the dress-up? Nerdy Jacob knows that his father favours his jock brother, Esau, and that he does so on account of his prowess as a hunter and his more masculine traits. Indeed, his mother may have told him that Isaac plans to bless Esau and leave Jacob with no blessing at all. If Isaac were to feel Jacob’s smooth and hairless skin and his softer clothing, he would think it ridiculous to bless him: such a son, seemingly so much less manly than Esau, was manifestly unsuited to bear his blessing and legacy. Isaac already seems to have intended to leave Jacob with no blessing; were Jacob to come into Isaac’s presence and seek a blessing for himself without anything to commend him to his father’s favour, he might even end up with a curse! The goat skins and Esau’s hunters garments are used so that Jacob can play the part of a son that Isaac will bless. Dressed up as a rough outdoorsman, perhaps his father will not lightly dismiss him. At least, this, argues Fohrman, was Rebekah’s intention.

Fohrman also argues that, even though she had the prophecy that her older son would serve the younger, Rebekah would have been quite unjustified to deceive her husband. While deception may be warranted on occasions, obtaining the blessing through an outright lie would not be such a case (such a lie would be different in kind from the protective lie told by Rahab, for instance). The end would not justify the means.

Things all went wrong when, questioned by his father, Jacob claimed to be Esau. Rather than making a case for himself as Jacob, Jacob pretended to be his older brother. The success of the deception might seem bizarre to the reader. Jacob’s voice is recognizably his own, but Isaac was not expecting a visit from his younger son. He was expecting Esau, whom the visitor claims to be, but not so soon. Isaac is surprised and wants to confirm that the visitor is in fact Esau, wanting to feel him. Even after feeling him, Isaac’s senses give him a conflicting report: his ears tell him that it is Jacob, but the feel of the visitor’s hands is like Esau’s. After he eats the food and smells Jacob, he readily blesses him, dismissing his earlier uncertainty. Isaac’s blindness, his failure to attend to his sense of hearing, and his privileging of touch, taste, and smell over it, is an indictment upon his character.

Fohrman adds further important details to the mix when he observes the way that, at the ford of the Jabbok, fundamental themes in Jacob’s life resurface. Jacob was given an unflattering name (‘usurper’) at his birth; he tricked his brother out of his birthright and deceived his father to obtain the blessing. At the end of Genesis 32, just before meeting up with his brother again for the first time in a couple of decades, Jacob wrestles with the mysterious figure at the Jabbok (a place which mixes up the letters of his name). Refusing to let go of the figure, Jacob receives a new name and a blessing. Notably, when he meets with Esau again immediately afterwards, Jacob bows to him seven times. He freely offers his brother the lion’s portion of the wealth he has gained and calls him ‘lord’. He insists that Esau accept his ‘blessing’ (33:11). He allows Esau to go ahead of him.

Fohrman suggests that these episodes imply a resolution to the conflict that has dominated Jacob’s life to this point. His grappling with Esau in the darkness of their mother’s womb, from which he emerged grasping his brother’s heel, his struggle with Esau in the ‘darkness’ of his blind father’s tent, and his wrestling with the figure in chapter 32 are three paralleled episodes. At the end, having received a new name and a blessing from God, Jacob can performatively restore to Esau what he took from him. This suggests that, not only was the deception of Isaac unjustified, it was also unnecessary: Jacob ends up receiving the true blessing and his name by a different means entirely.

I find Fohrman’s argument that Rebekah did not intend for Jacob to deceive Isaac a very thought-provoking one, even though I am not entirely persuaded of it. His points about the connection between the events at and after Jacob’s wrestling at the ford of the Jabbok are, to my mind, much stronger, and weigh against Jordan’s reading of the deception of Isaac.

I believe that important intertexts for our reading of the story of Jacob are found in Genesis 3 and 4: the stories of the Fall in Eden and Cain’s killing of Abel. Esau is a beast-like man, a ruddy and hirsute predator of the field, the realm of the beasts. Jacob, by contrast, is a domesticated man of tents, a smooth man, without the beast-like hair of his brother. Yet he is cunning and, as a crafty man, has much in common with the serpent, who is smarter than the beasts of the field. The contrast between Esau and Jacob is akin to that between Cain and Abel; of course, Cain, another predatory man of the field, also sought to kill his younger brother when his brother was favoured over him.

Jacob came out of the womb clutching his brother Esau’s heel (Genesis 25:26). The last figure associated with an assault upon the heel was the serpent himself (Genesis 3:15). As with the man and the woman in the story of the Fall, Esau is driven by desires and appetites, without a clear sense of that which is good. He surrenders something of immense value for a ‘mess of pottage’.

In the story of the stew, Jacob is in the role of the serpent, while Esau is Adam. David Daube notes that Esau’s description of Jacob’s stew as the ‘red red thing’ suggests that he might have thought it to be blood soup—forbidden food. We are told Esau was called ‘Edom’—Red—on account of his sale of his birthright for the red stew. The name Edom (אדום), mentioned at this critical moment, also sounds somewhat similar to another important name—Adam (אדם).

Isaac, like his son Esau, also acts rashly, carelessly giving up something of immense value for the sake of food offered by Jacob. Like Esau’s earlier selling of his birthright, Isaac’s actions occur as he presumes that he is about to die. Jacob gains the blessing through deception, while Esau receives something reminiscent of the curses of banishment received by the serpent and Cain (Genesis 3:14; 4:10-12): “Behold, away from the fatness of the earth shall your dwelling be, and away from the dew of heaven on high.”

As in other cases, the intertexts play out in multifaceted and complex ways, rather than as a straight mapping of one text onto another. Rebekah could be likened to Eve, fatefully giving food to her husband. Rebekah’s clothing of Jacob with skins might recall the Lord’s clothing of Adam and Eve with skins. The themes of death, curse, food, heeding the voice of the woman, and loss of birthright might also unite the stories. The serpent-like deceiver and those who heed their lower senses and obey their stomachs, rather than the voice of the Lord also might connect the stories. What we are to make of such possible connections requires much more reflection.

I think that a key further clue to the interpretation of Genesis 27 is found in the story of David, where several events recalling the stories of Jacob, Esau, Isaac, and Rebekah are found. In the books of Samuel, David is a figure who is reminiscent of both Esau and Jacob in different ways. David and Esau are the two biblical characters described as red or ruddy (Genesis 25:25; 1 Samuel 16:12; 17:42). In chapter 25, David acts as Esau did in Genesis 32:6, coming with four hundred fighting men to attack Nabal (1 Samuel 25:13—notably, ‘Nabal’ is ‘Laban’ backwards), before being pacified by a wave of gifts from Abigail, who behaves like Jacob. David is a man who dwells with the flocks in tents. While he is not a hunter like Esau, he is able to kill the predators: the lion and the bear, and later Goliath the serpent-like giant. He brings together traits of Esau and Jacob.

His interactions with Saul and Jonathan recall Jacob’s interactions with Esau, Isaac, and Laban, but with Esau especially. Like Esau, Saul is a foolish man who despises his birthright, losing it as a result. Jonathan, however, is like a good version of Esau. His greeting of David in 1 Samuel 20 recalls Esau’s greeting of Jacob in Genesis 33. While David refused the garments of Saul when they were offered to him in 1 Samuel 17:38-39, he received the garments of Jonathan in 18:4. Jonathan is the heir who willingly gives his place to the younger, recognizing the Lord’s purpose and fitting the younger for his role. He did what Esau should have done.

Two crucial episodes are found in 1 Samuel 24 and 26, episodes that recall Genesis 27. In both occasions, the first in the darkness of the cave and the second in the ‘darkness’ of a deep sleep from the Lord, David has the opportunity to take Saul’s life and to gain the kingdom as his inheritance. On both occasions, he resists the temptation. Even though the Lord had said that he would receive the kingdom, he must not grasp at it unlawfully, but must receive it in a rightful manner. As I have written of the episode in chapter 24 before:

In the conversation that follows, where David’s righteous restraint in seeking to take the inheritance for himself is revealed, Saul’s words, ‘is this your voice, my son David?’ recall the interaction between Jacob and his blind father Isaac. The chapter ends with Saul declaring that David is more righteous than he is, that the kingdom will be established in his hands, and blessing him. Here I believe we find a key to understanding the complicated story of the deception of Isaac. Here Jacob steps back from snatching the blessing and inheritance from the blind father, yet receives it nonetheless, on account of his righteousness.

The same question, ‘is this your voice, my son David?’ is found in 26:17. Like Esau in Genesis 27, Saul lifted up his voice and wept (24:16; cf. Genesis 27:38). In contrast to Genesis 27, while Jacob grasped at the blessing through deception and his brother sought to kill him, David refused to grasp the inheritance before the proper time and was blessed by his rival as a result. His rival, who had been seeking his life, also (temporarily) came to be at peace with him, in contrast to Esau, who sought to kill Jacob after he obtained the blessing through deception.

Putting some of these pieces together, it seems to me that both Genesis 27 and the story of David can fruitfully be read against the backdrop of the story of the Fall. Esau is like a brute beast, while Jacob plays the part of the crafty serpent. Yet Jacob must learn to be the complete man that he is, receiving the blessing not through subterfuge but faith. In this, David exemplifies true maturity. He is cunning like Jacob and strong like Esau. He is a quiet man of tents like Jacob, yet also an able warrior and defender in the field. Waiting for the Lord’s good time, he receives the birthright and blessing.

A further aspect, which I will only gesture towards here, is the possible connection between Jacob and Esau and the Day of Atonement/Yom Kippur ritual. As in other episodes in Genesis—most notably Ishmael and Isaac (Genesis 21 and 22), Joseph and Judah (Genesis 37 and 38), and Perez and Zerah (Genesis 38)—the story of Esau and Jacob involves a pair of brothers or twins who have divergent fates, described in ways that might allude to the ritual of Leviticus 16. Ishmael is sent out by Abraham into the wilderness by the hand of his mother, Hagar. In a paralleled account in the chapter that follows, Isaac, the other son of Abraham, is offered as a sacrifice on the mountain of the Lord. In Genesis 37, Joseph’s death is faked using the blood of a goat presented to the father for recognition. In the chapter that follows, Judah sends a goat into the wilderness by the hand of Hirah the Adullamite. Perez and Zerah are divided by the fact that one of them has a red cord, much as the two goats on the Day of Atonement traditionally were divided.

Goat themes are important in the story of Esau and Jacob. There are two goats used in Genesis 27, much as on the Day of Atonement. Seir (the place where Esau settled), the word ‘hairy’, and a word for a he-goat are related or pun off each other in the Hebrew. The ‘redness’ of Esau (his skin and the name, Edom, he receives as a result of the ‘red red thing’ that he requests from Jacob in chapter 25) would also connect him with the scapegoat, which is distinguished by the red cord.

Esau is the scapegoat who departs from the land to Seir, whereas Jacob journeys on to Succoth in Genesis 33:17-18. Gershon Hepner suggests that Jacob’s movement to Succoth after parting ways with Esau is suggestive of the way that the feast of Succoth immediately follows Yom Kippur in Leviticus 23.

If this is correct—I think it probably is—the presence of Day of Atonement/Yom Kippur themes provide a ritual framework for interpreting the Jacob and Esau stories. They are the twin goats with divergent destinies, one to be cast out and the other to be raised up. Their fates, though divergent, are intertwined. As Jordan has noted, Genesis 27 has something of the form of a narrative of sacrifice (an offering of food in search of covenant blessing). Genesis 28, the story of Bethel that follows, might continue the theme: Jacob symbolically enters the Most Holy Place, seeing his vision of the ladder reaching to heaven and the Lord standing above it. There is a lot more that could be said about these connections, but I will leave fuller reflection upon them as an exercise for the reader!

A Fitting Epilogue

The conclusion of John’s gospel—the account of the miraculous catch of fish and Christ’s resurrection appearance by the Sea of Tiberias—might seem to be a rather peculiar epilogue to the Evangelist’s account. The disciples return to Galilee and to their fishing, perhaps a surprising development after the excitement of the resurrection, the extreme focus upon Jerusalem in the rest of the gospel (especially in the events of Holy Week and the first resurrection appearances), and the absence of references to their fishing elsewhere in John.

In the Synoptics, by contrast, the Sea of Galilee is centrestage for much of the earlier parts of their accounts and we are often reminded of the fact that several of the disciples were fishermen. Why would the text move its focus back to Galilee and to fishing at this final moment? Is John 21 more than an awkward appendix to the book? As it is Eastertide, I thought it might be worth giving some very brief thoughts on this question. Here are a few reasons why John 21 is a perfect and fitting conclusion to the gospel.

1. It is a restoration narrative. Peter and some of the other disciples were first called with a miraculous catch of fish (Luke 5:1-11). John likely presumes knowledge of such an account. The final appearance of Jesus in John recalls the first call of Peter as he is recalled to his task. The charcoal fire, as many have noted, recalls the charcoal fire at which Peter denied Jesus in 18:18, and the three times Jesus asked him whether he loved him recalls the three occasions of Peter’s denial.

2. In the initial call of the disciples, they were summoned to follow Jesus and become fishers of men. John 21 is a symbolic recommissioning and assurance of the success of their mission. The miraculous catch is a great sign of their success in the mission to come. The movement from Jerusalem and the land out towards Galilee and the Sea is important here: the disciples’ mission will lead them out into the wider world.

3. Throughout the gospel there is a running theme of the gift of living and healing water. Among other connections: the conversation at the well in John 4, Jesus’s speech on the last great day of the feast in John 7, water and blood flowing from his pierced side in John 19. This gift of living water draws upon Old Testament imagery. Most notably, it recalls the living and healing water flowing from the side of the temple in Ezekiel 47, water that healed brackish waters so that many fish could be caught (see also Zechariah 14:8). It also recalls the struck rock in the wilderness, the opened garden fountain in Song of Songs 4:12-16, and the rivers flowing from Eden in Genesis 2. Jesus, the living temple, gives from his pierced side the living water downstream of which the Church will catch great quantities of ‘fish’. Richard Bauckham has observed an allusion to Ezekiel 47 in the 153 fish. It should also be recognized that, like John, Revelation concludes with allusions to the water flowing out from the temple in Ezekiel 47 (I have written more about some of the relevant themes here).

Once we recognize such features, the conclusion of John’s gospel could not be more fitting. It returns us to the beginning, recalling the first call of the disciples. It restores Peter from his denial, so that he can lead the other disciples forward. It is a promissory sign of the success of the Church’s gospel mission. It is a culmination of the threads of Old Testament scriptural allusion that hold the book together. And, in its allusions to Ezekiel 47, it connects the conclusion of the Gospel of John to the conclusion of John’s book of Revelation.

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ Mere Fidelity has released an episode on the resurrection in John’s gospel.

❧ The Theopolis Podcast’s Deuteronomy series continues, with episodes on Deuteronomy 24: Man-Stealing, Leprosy, and Loans, Deuteronomy 24: Oppressing Hired Workers and Death for Sin, and Deuteronomy 24: Perverted Justice and Reaping a Harvest.

❧ I joined Jordan Bush on the Thank God for Nostr podcast to discuss the benefits and dangers of social media.

❧ Plough published a piece of mine: Why I Went Cold Turkey on Political Theology.

It is possible that, reading this, you find yourself in a similar position to the one I was in as a young man. Some teaching has captured your imagination and is increasingly animating your life. While that teaching may initially pass as biblical, your life and the movements to which you belong do not seem to be producing good fruit. You may find it easy to resist arguments against your position yet have an uncomfortable sense that something is amiss. It is for such situations that we must practice testing the spirit of the teachings that we sow in our lives, the quality of the soil that receives them, and what yield comes from them.

❧ My long-running Revelation series on the God’s Story Podcast was concluded over the last few weeks: Revelation 21 and Revelation 22.

❧ My series of videos for Theopolis on the controls upon our reading conclude with the following:

Cumulative Reading and the Cutting Room Floor

Reading the Bible Poetically and Musically

Virtues and Bible Reading

Upcoming Events

❧ Alastair will be out in the Bay Area in a week’s time, delivering a two-day course on a biblical theology of the sexes: Beyond Rules and Roles. You can still sign up for it here.

❧ Most of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Susannah and Alastair

Susannah: The history of political spin is on full display in those reliefs and the accompanying “Taylor Prism,” which is usually housed in the same room as them in the BM but which was temporarily removed when we were there. It’s also always fascinating to run into bits of “Bible history” out in the wild, like the moment that Dorothy Sayers realized that Ahasuerus from the story of Esther was the same Xerxes she’d learned about from Herodotus and Plutarch and so on.

Basically, things started out badly for Hezekiah. As Jeremiah (or whoever it was) wrote in 2 Kings,

In the fourteenth year of King Hezekiah’s reign, Sennacherib king of Assyria attacked all the fortified cities of Judah and captured them. [Immediate context makes it clear that this means all but Jerusalem.] So Hezekiah king of Judah sent this message to the king of Assyria at Lachish: “I have done wrong. Withdraw from me, and I will pay whatever you demand of me.” The king of Assyria exacted from Hezekiah king of Judah three hundred talents of silver and thirty talents of gold. So Hezekiah gave him all the silver that was found in the temple of the Lord and in the treasuries of the royal palace. At this time Hezekiah king of Judah stripped off the gold with which he had covered the doors and doorposts of the temple of the Lord, and gave it to the king of Assyria.

The Taylor Prism agrees on the basics here, on the dynamic of this attempted buyoff, and on the thirty talents of gold, but inflates the rest:

Fear of my greatness terrified Hezekiah. He sent to me tribute: 30 talents of gold, 800 talents of silver, precious stones, ivory and all sorts of gifts, including women from his palace.

The buyoff doesn’t work: if once you have paid him the Dane-geld/You never get rid of the Dane. The author of 2 Kings, Jeremiah or whoever it is, continues:

17 The king of Assyria sent his supreme commander, his chief officer and his field commander with a large army, from Lachish to King Hezekiah at Jerusalem. They came up to Jerusalem and stopped at the aqueduct of the Upper Pool, on the road to the Washerman’s Field. 18 They called for the king; and Eliakim son of Hilkiah the palace administrator, Shebna the secretary, and Joah son of Asaph the recorder went out to them.

19 The field commander said to them, “Tell Hezekiah:

“‘This is what the great king, the king of Assyria, says: On what are you basing this confidence of yours? 20 You say you have the counsel and the might for war—but you speak only empty words. On whom are you depending, that you rebel against me? 21 Look, I know you are depending on Egypt, that splintered reed of a staff, which pierces the hand of anyone who leans on it! Such is Pharaoh king of Egypt to all who depend on him. 22 But if you say to me, “We are depending on the Lord our God”—isn’t he the one whose high places and altars Hezekiah removed, saying to Judah and Jerusalem, “You must worship before this altar in Jerusalem”?

23 “‘Come now, make a bargain with my master, the king of Assyria: I will give you two thousand horses—if you can put riders on them! 24 How can you repulse one officer of the least of my master’s officials, even though you are depending on Egypt for chariots and horsemen? 25 Furthermore, have I come to attack and destroy this place without word from the Lord? The Lord himself told me to march against this country and destroy it.’”

26 Then Eliakim son of Hilkiah, and Shebna and Joah said to the field commander, “Please speak to your servants in Aramaic, since we understand it. Don’t speak to us in Hebrew in the hearing of the people on the wall.”

27 But the commander replied, “Was it only to your master and you that my master sent me to say these things, and not to the people sitting on the wall—who, like you, will have to eat their own excrement and drink their own urine?”

28 Then the commander stood and called out in Hebrew, “Hear the word of the great king, the king of Assyria! 29 This is what the king says: Do not let Hezekiah deceive you. He cannot deliver you from my hand. 30 Do not let Hezekiah persuade you to trust in the Lord when he says, ‘The Lord will surely deliver us; this city will not be given into the hand of the king of Assyria.’

31 “Do not listen to Hezekiah. This is what the king of Assyria says: Make peace with me and come out to me. Then each of you will eat fruit from your own vine and fig tree and drink water from your own cistern, 32 until I come and take you to a land like your own—a land of grain and new wine, a land of bread and vineyards, a land of olive trees and honey. Choose life and not death!

“Do not listen to Hezekiah, for he is misleading you when he says, ‘The Lord will deliver us.’ 33 Has the god of any nation ever delivered his land from the hand of the king of Assyria? 34 Where are the gods of Hamath and Arpad? Where are the gods of Sepharvaim, Hena and Ivvah? Have they rescued Samaria from my hand? 35 Who of all the gods of these countries has been able to save his land from me? How then can the Lord deliver Jerusalem from my hand?”

36 But the people remained silent and said nothing in reply, because the king had commanded, “Do not answer him.”

37 Then Eliakim son of Hilkiah the palace administrator, Shebna the secretary, and Joah son of Asaph the recorder went to Hezekiah, with their clothes torn, and told him what the field commander had said.

When King Hezekiah heard this, he tore his clothes and put on sackcloth and went into the temple of the Lord. 2 He sent Eliakim the palace administrator, Shebna the secretary and the leading priests, all wearing sackcloth, to the prophet Isaiah son of Amoz. 3

I find this whole scene incredibly moving and also telling in that Eliakim, the steward whose office prefigures that of St. Peter, asks the field commander to not speak in Hebrew, but he insists on doing so so that the people of the city will overhear and be discouraged. This is a story about wartime propaganda and how not to lose one’s nerve, both on a personal and on a national level.

Hezekiah sends for Isaiah, who says to the messengers,

“Tell your master, ‘This is what the Lord says: Do not be afraid of what you have heard—those words with which the underlings of the king of Assyria have blasphemed me. 7 Listen! When he hears a certain report, I will make him want to return to his own country, and there I will have him cut down with the sword.’”

And Hezekiah takes heart. But then Sennacherib sends messengers to Hezekiah again telling him that his god is deceiving him:

Surely you have heard what the kings of Assyria have done to all the countries, destroying them completely. And will you be delivered? 12 Did the gods of the nations that were destroyed by my predecessors deliver them—the gods of Gozan, Harran, Rezeph and the people of Eden who were in Tel Assar? 13 Where is the king of Hamath or the king of Arpad? Where are the kings of Lair, Sepharvaim, Hena and Ivvah?”

Nowhere, that’s where.

This message is delivered by letter, and Hezekiah brings the letter to the Temple, and “spreads it out before the Lord,” either unrolling a scroll or putting down a series of cuneiform tablets, presumably in front of the entrance to the Holy of Holies. He prays:

“Lord, the God of Israel, enthroned between the cherubim, you alone are God over all the kingdoms of the earth. You have made heaven and earth. 16 Give ear, Lord, and hear; open your eyes, Lord, and see; listen to the words Sennacherib has sent to ridicule the living God.

17 “It is true, Lord, that the Assyrian kings have laid waste these nations and their lands. 18 They have thrown their gods into the fire and destroyed them, for they were not gods but only wood and stone, fashioned by human hands. 19 Now, Lord our God, deliver us from his hand, so that all the kingdoms of the earth may know that you alone, Lord, are God.”

And God gives Isaiah a prophecy in answer to Hezekiah’s prayer, a message for Sennacherib:

Because you rage against me

and because your insolence has reached my ears,

I will put my hook in your nose

and my bit in your mouth,

and I will make you return

by the way you came.’this is what the Lord says concerning the king of Assyria:

“‘He will not enter this city

or shoot an arrow here.

He will not come before it with shield

or build a siege ramp against it.

33 By the way that he came he will return;

he will not enter this city,

declares the Lord.

34 I will defend this city and save it,

for my sake and for the sake of David my servant.’”35 That night the angel of the Lord went out and put to death a hundred and eighty-five thousand in the Assyrian camp. When the people got up the next morning—there were all the dead bodies! 36 So Sennacherib king of Assyria broke camp and withdrew. He returned to Nineveh and stayed there.

This whole story so far has been one of messages sent from kings to each other and kings to God and God to kings, and also, distinctly, of the need to keep up the nerve of a citizenry. Sennacherib is good at propaganda: he doesn’t succeed in breaking the nerve of the inhabitants of Jerusalem, but he does his best, he knows it’s important. As for his own people, he’s equally attentive to the need for spin.

Basically, Sennacherib takes Lachish and other cities, gets to the gates of Jerusalem but fails to take it, as described in 2 Kings. Then, once he’s home, spins his failure by having the following inscribed on the Taylor Prism (and at least two others, one now in Chicago and one in Jerusalem):

As for Hezekiah, the Jew, who did not submit to my yoke, 46 of his strong, walled cities, as well as the small cities in their neighborhood, which were without number,-by levelling with battering-rams (?) and by bringing up siege-engines (?), by attacking and storming on foot, by mines, tunnels and breaches (?), I besieged and took (those cities). 200,150 people, great and small, male and female, horses, mules, asses, camels, cattle and sheep, without number, I brought away from them and counted as spoil. Himself, like a caged bird I shut up in Jerusalem his royal city.

But he does not even attempt to claim that he took it.

As an avid fan of the Theopolis podcast—especially James Jordan’s Life of Jacob series—I appreciate hearing your take on Jacob, I’ve always wondered you, Peter Leithart, and others make of some of Jordan’s more controversial interpretations.

It would be cool to see a Theopolis podcast on “James Jordan’s Hot Takes” where the podcast crew shares their thoughts on some of his interpretations. For example: did Elijah actually die? Did the apostles really stay in the Israel area before AD 70? Is Jacob the perfect man? Can the canon be rearranged in books of seven resembling the days of creation? I’m sure there are more!

Nothing like a day at the BM. Or two, or three.

The things which, to me, blunt the notion of Jacob's trials as God's discipline for his deception are "Christ learned obedience through what he suffered" and "be shrewd as serpents". To me, Jacob's trials are character formation rather than payback. I think the deception was obedient.