№ 34: A Return to Ireland

And some remarks on the sacrificial system for the uninitiated

Alastair: Our previous Substack post was published on May 14th, our second wedding anniversary. We celebrated the occasion by going to the restaurant where we ate on the evening of our wedding. Considering the amount that has happened within the time, I struggle to process the fact we have been married for little more than two years. While marriage has slightly reduced my productivity on the writing front, the amount that we have packed into our two years of life together still amazes me. Despite several external challenges and pressures, the last couple of years have been so rewarding and joyful. Sharing life with Susannah never ceases to be a delight and a privilege.

Since our last post, we have gone to a colloquium in Birmingham, Alabama, attended a wedding in New York, and spent ten days in Ireland. I am writing this in Dublin Airport, while waiting to board our flight to New York. It has been wonderful to connect and spend time with several friends, old and new, over this period. An especial treat has been meeting some online friends in person for the first time. Although I have deep reservations about the Internet, I often am astonished when I consider the fact that I have met literally hundreds of people with whom I first became acquainted online in person over the last two decades.

The days before our Birmingham trip were very busy, as I tried to get on top of work and correspondence before we left. Unfortunately, I was not as successful as I had hoped to be and have a growing backlog of tasks I will be struggling to reduce on our return to New York. We did, however, enjoy an evening watching The Night of the Hunter, which our friend Hannah recommended to us. We also had a Pentecost potluck at our church.

I have been involved in the Theopolis Institute’s Civitas group since 2019 and Susannah joined in 2021. The group meets in person for a couple of days two or three times a year. Over several sessions, about a dozen selected participants discuss questions of political theology, focusing on set readings for each session. We flew to Birmingham for the latest Civitas gathering, within which we focused upon three books: Benedict Anderson’s, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, the Ronald Beiner edited volume Theorizing Nationalism, and Bernard Yack’s Nationalism and the Moral Psychology of Community. Especially as nationalism has been a live field of conversation in some of our contexts, it has been refreshing to discuss issues related to it in such a careful and patient manner, not having to compete with the loudest voices online or keep pace with conversations on social media. During our Birmingham visit, we also had the opportunity to meet up with Susannah’s former pastor and his family.

We had to miss the final couple of sessions of the Civitas meeting as we had to get back to New York for the wedding of some friends, a truly joyous occasion. I had the honour of giving one of the readings and delivering a short speech at the reception. Seeing wonderful friends marrying each other never gets old!

Although I am English, born in Worcester, I moved over to Ireland at the age of three months. The first sixteen years of my life were spent in the town of Clonmel in the Republic of Ireland, where my father planted a church. I had neither returned to Clonmel, nor properly visited Ireland again in over twenty years, and Susannah had never visited, so when we were invited to join some friends for a holiday, we jumped at the opportunity. We had the most memorable time—next to our honeymoon, perhaps the most wonderful time we have spent together.

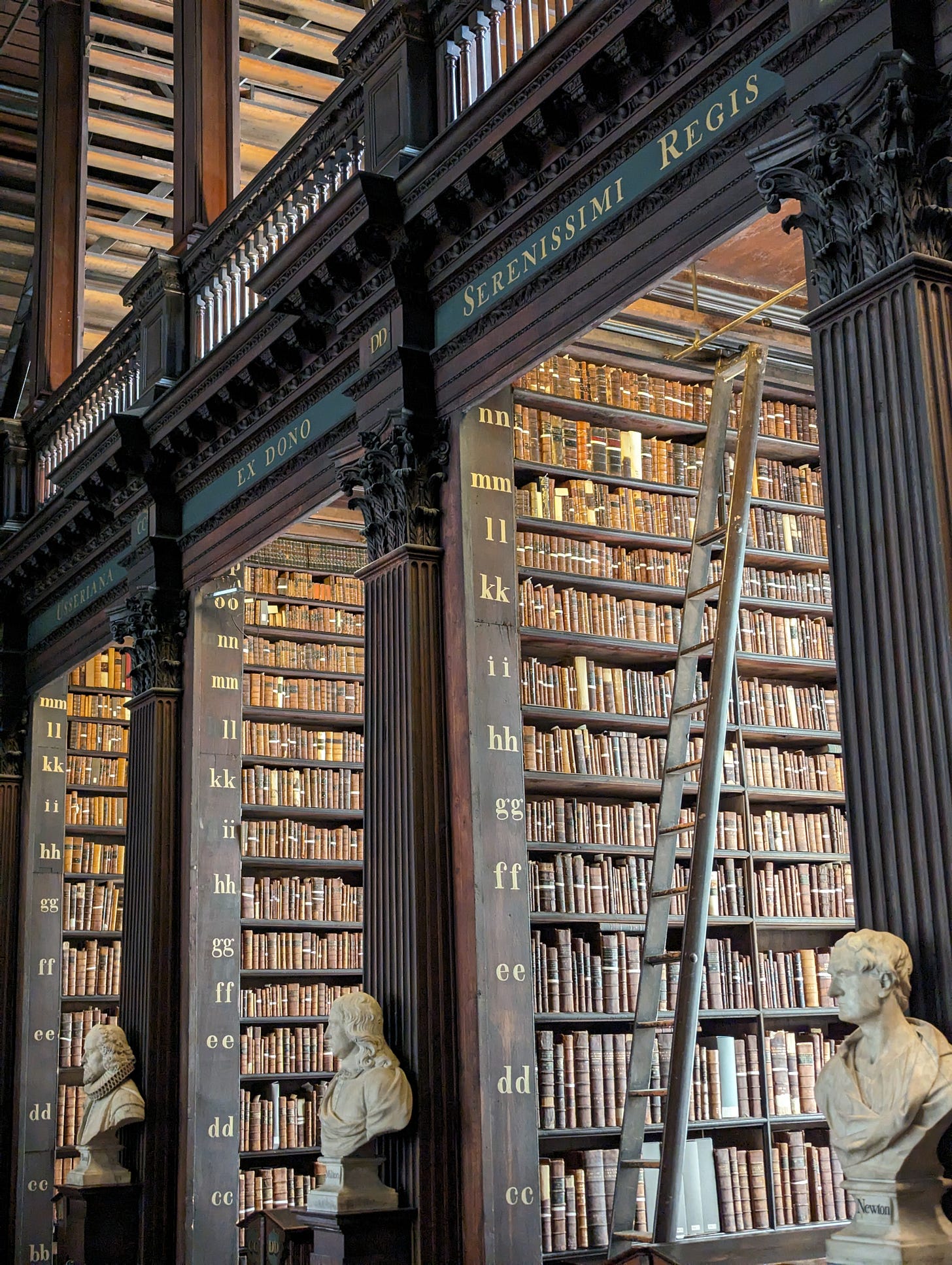

Our trip began in Dublin, where we visited Trinity College, seeing the Book of Kells and its famous library. Restoration work was being done on many of the books, so most of the shelves were empty, but the Long Room was still breathtaking.

Having not slept on the overnight flight over, we all retired early and had an early start the next morning. Before we did so, we took the opportunity to visit the Dublin ‘portal’, which has a streaming video connection to New York City. We will likely visit the New York portal at some point after our return.

Before we left Dublin, we visited St Patrick’s Cathedral, which has connections to Dean Jonathan Swift and Archbishop James Ussher. We attended a service and then looked around the building. There were eight of us, so we travelled around the country in a large van, reading poems, listening to music, and telling stories along the way.

As a sailor, Susannah was excited to visit the Maritime Museum in Dún Laoghaire, which we went to before leaving the Dublin area. Susannah needed to get some work done, so while she worked outside of the museum, I went down to the harbour and walked out on the pier. I sent her some photos of the boats in the harbour and she insisted that I tell her where I was. In the remaining minutes before we were due to leave, she made her way quickly down and we met halfway along the pier. The sun had come out and being next to the sea was exhilarating.

That evening was one of the highlights of the trip, as we stayed in a fifteenth century castle, to my recollection the first time that I have ever done so. From the roof of the castle, we could look out over the River Suir, the river that runs through Clonmel. The eight of us shared a meal in the castle that evening, during which we had the opportunity to get to know each other a lot better, moving outside afterwards to talk further, long into the night.

The next morning and early afternoon, we visited Clonmel. While we did not get to see any of my childhood acquaintances, we saw several places that were central to my life growing up: my church, my home and street, and the schools I attended. I grew up in a Georgian terraced house on a street directly opposite Old St Mary’s Church, a Church of Ireland building that in its first form dates to the beginning of the 13th century. Several neighbours I remembered from growing up there still lived in the street, over thirty years later. The walls of the old town of Clonmel surrounding the church famously mark the site where Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army suffered its most devastating losses ever.

Clonmel is a small town surrounded by lush green hills; its name, Cluain Meala in Irish, means ‘Vale of Honey’. In most respects it did not seem to have changed that much in its appearance in the twenty years since I last visited. I recognized dozens of buildings and stores that looked much as they had done in the 1990s (you can get a sense of the Clonmel that I remember in this series of videos). Several of the locals we talked to gave us a sense that the town had been stagnating over the past years, suffering from the loss of commerce in its centre, among other things. There were also some cultural changes evident beneath the surface; when I lived there, for instance, Catholicism was a much more powerful force in Irish society. Much has changed on that front since the 1990s.

From Clonmel we drove about thirty minutes to the imposing Rock of Cashel, the seat of the kings of Munster and the site where it is claimed that the king of Munster was converted by Saint Patrick. While many of the structures are in ruins, the site is remarkable and awe-inspiring. I visited it many times as a child and, like many of the things that I saw on the trip, it was interesting to compare my childhood impressions with my adult ones.

We stopped off for a meal in Mallow before travelling on to Killarney, which would be our base of operations for the days that followed. The next day was a quieter one. We spent time in the town, shopped, got some work done, read, and Susannah and I made a meal for the group.

The next day was packed. We started the morning with a jaunting car (horse carriage) ride around Killarney National Park, stopping off to walk to a waterfall.

After the jaunting car ride, we drove to Dingle, where we had an incredible meal and looked around the harbour.

From Dingle we did the Slea Head Drive, part of the Wild Atlantic Way. Once again, we were blessed with the most glorious weather and were able to appreciate one of the most scenic drives in Ireland at its best.

We stopped off at a beach before continuing the drive, but had to reverse and change direction. We had been doing the loop against the flow of much of the traffic and encountered a significant bottleneck on the single lane road, where there were few passing points, so we turned around and did the route in the other direction. At one point we stopped and several of us carefully climbed down to a ledge, where we looked out over the sea. We ended up in the most westerly pub in Ireland, where we had a pint.

The next day, half of our group went to climb Mount Carrauntoohil, while Susannah and I remained in the house, doing some work and spending time with the two others of our party who had stayed behind - the nine year old and the 16 year old. In the afternoon, we ventured into the town and did some shopping. Then we walked out to the picturesque Ross Castle. We had hoped to see inside the castle, but it had closed just before we arrived, so we took another jaunting car ride instead.

The jaunting car ride was a very good decision. The park was fairly empty by that point, but the light was glorious and the views of Ross Castle were breathtaking. We also were able to see several deer.

The next day, Sunday, we worshipped in the local Church of Ireland in Killarney, the Church of the Sloes, which shares its name with the town (Cill Airne). The congregation was small and a large proportion were attending for the baptism of a child of one of the church’s families: the baby boy was, as far as we could tell, their eighth. Baptisms are always special, and it was a blessing to be able to share the occasion with fellow Christians.

From Killarney we drove up to the small seaside town of Kinvara, in the southwest of County Galway, near the border of County Clare. We walked out to Dunguaire Castle, just outside of the town, before ending the evening.

The next day we decided to go south to visit the Cliffs of Moher and the Burren, two sites of great natural interest. We passed through Lisdoonvarna, giving me occasion to introduce Susannah and the rest of the group to Christy Moore’s famous song. Over the rest of the trip, we played the song on many occasions, loudly singing along and annoying Susannah considerably. It was still earworming for her earlier today. [Susannah: It’s NOT FUNNY.]

We were fortunate enough to arrive in time to see the Cliffs of Moher clearly, but as we walked out past O’Brien’s Tower, a mist came in from the sea, shrouding much of them for the remainder of our visit. It is hard adequately to convey their scale: you may get a sense from picking out the dots of the figures of the walkers in the photos. Besides the awe-inspiring character of the cliffs, the beauty of the path along the clifftop, flanked by wildflowers, left a strong impression.

From the cliffs we drove into the Burren, where we decided to stop at the Poulnabrone dolmen, the oldest dated megalithic site in Ireland. The estimated dating of the site stretches back millennia before Christ - more than 5000 years before the present. The dolmen is a portal tomb, situated on the distinctive karst landscape of the Burren, surrounded by its limestone pavement. It is difficult to comprehend its extreme age, likely predating Stonehenge and all but a very few of the prehistoric sites of Europe. We returned to Kinvara that evening, for our final night there.

The next day, the final day we would all be together, we had to drive back to Dublin. We had decided that we would visit Glendalough before going into Dublin and were extremely glad that we did. Glendalough is the location of a famous medieval monastic settlement, associated with St Kevin. It was founded in the sixth century and is perhaps best known for its iconic round tower.

From the centre of the monastic settlement, we walked along the small lake and up to Poulanass Waterfall. Then we descended to the Upper Lake, where, as the sun came out, we enjoyed the most sublime views.

From Glendalough we drove into Dublin, where we went to the Guinness Storehouse for a tour. As such museums or tours go, the Guinness Storehouse was in the highest league, engaging, interactive, and attention-grabbing. The tour ended with a pint of Guinness at the bar at the top of the building with a 360° view over the city of Dublin.

We concluded our final night together with a meal and prayer. [Susannah: We also finished the last fifteen minutes of The Quiet Man, which we’d watched most of the previous night) and sang “The Parting Glass.” Just so grateful for these new friends.]

While the others returned on Tuesday, Susannah and I remained for one more day. I needed to teach a class at 5pm, so I was not able to return that day. We also wanted to meet up with a couple of friends in Dublin. We met with the first of our friends in the early afternoon. Susannah met up with the second shortly after my two-hour class began and I joined them for a meal and conversation after it was over. It was a delightful conclusion to an incredibly memorable trip.

After a smooth flight, we are now back in New York, with an insane amount of work to do!

Susannah: Well of course I spent a lot of time while we were in Ireland reading Yeats’ friend Lady Augusta Gregory’s compendium and retelling of the Legendarium of Ireland. Due to this I now have a good deal of confidence that I understand Irish prehistory from the neolithic through the Iron Age: there are lots of folk-wanderings of different people groups and pantheons of gods who later get demoted to various other statuses: the Tuatha dé Daanan, originally on par with the Olympians, become the faeries of later mythology, and so on. Other key sources and texts I dipped into included Mark Williams’ recent Ireland’s Immortals, and Lady Gregory’s friend James Stephens’ The Crock of Gold, plus of course Yeats himself.

It was extremely special to spend time with Alastair in a place that is still so much a part of him—and to begin to learn a whole new set of ideas and histories and political and religious complexities. I just know so little, still. But I love that feeling: the beginning-feeling.

The Levitical System for the Uninitiated

Many a well-intentioned programme to read the Bible through in a year has foundered upon the rocks of the book of Leviticus. If the instructions for building the tabernacle and the description of its construction at the end of Exodus seem tedious, at least they are not anywhere near as strange and foreign as the book that follows.

To understand the sacrificial system, we need to inhabit a very different mode of sense-making in the world, one that is strange to us, although perhaps not altogether as foreign as we might at first think. While we largely understand the world through abstractions presented to the detached eye of theoretical reason, the sacrificial system is addressed to people who understood the world through a more practical, poetic, and concrete logic. Such a form of sense-making is a great deal more sophisticated than moderns typically appreciate and, when grasped, may reveal just how limited our ways of inhabiting and interpreting the world can be by comparison.

As children of the modern world, we tend to think about things in terms of abstract and disembodied concepts. Christians, for instance, can be tempted to regard the tabernacle and sacrificial system as ‘pictures’, particularly of Christ. The point, we suppose, is to reflect upon the pictures and see what ideas they are teaching. There is some element of truth there, but it is also rather misleading. The tabernacle and the rites of the sacrificial system were designed to be inhabited as symbolic objects and practices that ordered them towards a reality encountered within them. They were not primarily designed to be looked at from without and translated into abstract ideas.

The whole sacrificial system, for example, was an extensive poetic mapping of Israel’s life onto the animal and vegetable realm of creation, ordered around an architectural symbol—the tabernacle that was, among various other things, a macrocosm of the human body and a microcosm of the creation—and practiced within the patterns set by celestial bodies and the earth’s seasons. Israel was to make sense of and articulate its existence and its fellowship with God in terms of this profoundly material and concrete reality. For Israel, the created cosmos was not merely a site for the operation of mathematical laws upon generic particles, nor a reservoir of raw material to be extracted and pressed into the service of humanity’s power, nor even primarily a realm of beautiful surface spectacles to gaze upon. It was a charged realm of meaning and communion, where the various objects of the world communicated different facets of divine truth.

Such a system of analogies casts the particular, concrete realm and its constitutive differences into sharp relief. The animals of the sacrificial system and the dietary laws, for example, presented Israel with a system by which to understand and be formed into its unique place in the world. Clean and unclean, sacrificial and non-sacrificial animals, and the many distinctions within each category were metaphorical frameworks within which Israel could practically arrive at a clearer apprehension of itself and its relationship with God.

The sacrificial system was a concrete framework designed to teach the art of discrimination in the realm of the particular. This contrasts radically with our abstract structures of thought. The people related to God through specific and symbolic sacrificial practices, in which the restoration of their relationship with and their new comportment of themselves towards God was symbolically enacted by them in the sacrificial rites.

Within such a framework, specific differences had great salience: male and female, Jew and Gentile, circumcised and uncircumcised, priest, ruler, and people, firstborn and later born, cooked and raw, seedtime and harvest, within and without the camp, clean and unclean, holy and common, feast, fast, and ordinary time, morning and evening, etc. These differences are highlighted through metaphorical and poetic frameworks of thought and practice that are designed both to bear considerable weight and to have authoritative and theological force. To sacrifice a donkey rather than a bull for the priest, for instance, would be a violation of truth, not merely the breaking of an arbitrary ritual command. It would be to say something untrue with one’s action. As a creature, the donkey symbolizes something different from the bull. The two are not interchangeable.

As a meaningful system of specific elements, the sacrificial system had a sort of linguistic character to it (Naphtali Meshel tries to present a ‘grammar’ of this system in his book on the subject). When we think of words, we might instinctively think of them as if they were tags referring to objects in the world. However, words also function within systems, playing off of the meaning of other words that are in some sort of relationship with them. For instance, the words ‘canine’, ‘doggo’, ‘dog’, ‘pet’, ‘very good boy,’ ‘Buster’, ‘hound’, ‘pooch’, ‘whippet’, or ‘mutt’ could all refer to the same creature. However, each of these terms has different connotations, evoking different fields of meaning and associations. The elements of the sacrificial system—the sacrifices, the rituals and their elements, the larger ceremonies, the tabernacle and its furniture, the priests, etc.—all belong within a great network of interrelated symbolism, within which countless analogies, associations, and contrasts are discovered.

When considering a sacrifice, for instance, you might ask questions like the following: Who is the offerer? What type of animal is offered? What species? What age? What sex? What actions are performed upon the animal before it is killed? Where is the animal killed? How is the animal divided? How are the parts disposed of, arranged, prepared, and/or eaten? Where does the blood go? What parts of the offering are eaten? By whom are they eaten? What parts were disposed of in some other manner?

Each one of these elements can differ from sacrifice to sacrifice, both distinguishing a sacrifice from and relating it to other sacrifices and elements of the wider system. The sacrifices often function like conjugations of a verbal root. Sacrifice as such can involve ascension of an offering on an altar, a blood rite, and a sacrificial meal. Yet Israel’s sacrifices varied in the prominence that was given to these elements. The ascension (or whole burnt) offering foregrounds the ascension of the offering on the altar. The purification (or sin) offering foregrounds the blood rite. The peace offering foregrounds the sacrificial meal. The fundamental template of rituals could be varied on unusual or exceptional occasions. For instance, the two goats on the Day of Atonement are an elaboration of the pattern of the sin offering. The ram of ordination in Leviticus 8 is a variation upon the peace offering, the variations making sense when you consider that the priests were not yet fully installed in their priestly office.

In books like Leviticus we are given fundamental templates for specific forms of sacrifices, and also see various forms of sacrifice joined together in particular ways for larger ceremonies such as the Day of Atonement. We also see deviations from the fundamental template could occur in specific cases. We should be especially attentive on such occasions, as the deviations are meaningful and also often illuminating of the underlying logic.

The system is one that depends upon and develops associations between different levels of reality. There is an instructive analogy between the legitimate sacrifice and the legitimate priest, for instance, as the physical unblemished integrity of the animal is presented as a symbol of the moral integrity and ritual cleanness of the person. The sacrifice for the priest had to be a male without defects and defects that disqualified a priest would also disqualify a sacrifice (Leviticus 21-22). As human life, society, and relation was mapped onto and symbolically enacted with a system of animals, architecture, furniture, agricultural seasons, and ritual, Israel could make sense of itself through participation in the mirror of symbol and ritual.

The sacrifices chiefly occurred within the order established by the tabernacle, a symbol of Sinai, the human body, the body politic, and the cosmos. As the various rooms and pieces of furniture of a house give shape and articulation to the different practices that occur within and around them, so the different zones of the tabernacle and its furniture gave shape and articulation to various aspects of itineraries of approach to the Lord.

The power of the sacrificial system is that as animals represented Israel and its various members, by performing sacrifice through symbolic substitutes, Israel could both represent and enact its own proper approach to God. The point of the rituals was always primarily as things to be performed, not primarily to be fodder for theologizing. The theology lay beneath the surface of the ritual texts and practices, implicit in the logic of their performance, and tended to surface through close attention to their place in a system as it emerges through comparative study of many texts. As the rituals were performed, we should presume that the theological meaning of proper approach to God was internalized through their metaphorical forms.

Even as moderns we are not entirely alienated from symbol and ritual. A wedding is a good example of a symbolic ritual that continues to play a powerful—if somewhat diminished—role in modern society. To go through the rigamarole of a wedding seems unnecessary to many. Surely all that matters is a man and woman’s personal intent to have a faithful, lifelong union! And, in exceptional cases, people can be considered as married without having gone through a ceremony or even, in some jurisdictions, without having registered their union. Yet the public ceremony, with its attendant rituals and symbols, is by no means unimportant. The public ceremony of the wedding plays out the greater transition that the joining of the couple represents; faithfully enacting and fully inhabiting the ceremonial drama is the means by which the real transition can best be accomplished and made sense of. The symbol is how we grasp the reality, the ceremony is how we experience and enact its transitions. The reality is most fully and deeply encountered in the symbol.

The purpose of the exchange of rings, for instance, is not to function as a ‘symbolic’ picture to convey ideas about a detached ‘reality’ to your spectating mind. An attractive ring of gold and a precious stone is a fitting symbol of the beauty and the unique value of a wife to her husband, the strength and endurance of his love for her, and the bond and commitment that now exists between the pair upon the body itself. The ring itself isn’t that love or bond, which could continue to exist even in its absence or in the case of its loss. However, the gift of the symbol is a means by which the reality itself is established, communicated, and known. The loss of a ring, even one of little monetary value, can be a cause of great sorrow, because something of the person’s symbolic purchase upon the reality of their spouse’s love for and commitment to them has been lost with it. A former husband’s reclaiming of the ring he once gave could be a devastating breaking of a reality effected through symbolic action.

All of this applied to the sacrificial system. The sacrifices were never mere pictures of theological concepts or of the nature of relationship with God, a sort of divinely-instituted flannelgraph. The sacrifices were the symbolic means by which the reality of relationship with God was experienced and known. Taking the sacrifices seriously and performing them faithfully manifested the seriousness of the relationship with God that they enacted. The tabernacle was a symbolic building, but God was really present to and with his people there and the structure of the building and its associated rituals provided frameworks within which the reality of people’s relationship to God could be lived out.

Hearing about the importance of symbol and ritual and the way in which realities are effected through and encountered in them seems to many moderns, alienated as they are from the symbolic order, to be a weirdly magical way of conceiving of the world: inappropriate for modern people; inappropriate also, perhaps, for Christians. In our scientific way of viewing the world, symbol and reality are not mutually constitutive. Rather, symbol is typically regarded as standing outside of reality as a signifying pointer to it. Entangling the two seemingly invites primitive and superstitious modes of thought.

Symbol certainly isn’t magic, even though it is effectual. As Hebrews argues, the blood of bulls and goats could never take away sin. The tabernacle was always patterned after and a copy of a greater realm of the Lord’s presence and was never the true archetype.

However, the objectivity of symbol and ritual is important to consider here. Symbols and rituals are not mere external expressions of private intentions. The sacrificial system was given by God as an objective means of approach to him, pre-existing any individuals’ intention to approach God in such a manner. The worshipper did not determine what the sacrifice meant or accomplished, but rather enacted the divinely established meaning and purpose, either faithfully or unfaithfully. As the rituals of sacrificial approach were objective, God-given ways of drawing near to him.

Although the sacrificial system was generally attended with a divine promise of efficacy, the prophets speak of the failure of sacrifice on account of wickedness and unbelief. Sacrifice was clearly not automatic. Rather, the efficacious practice of sacrifice presupposed the integrity of heart, ritual, and broader conduct. Where supposed worshippers were presenting sacrifices to the Lord, while their hearts were far from him or while they were wilfully persisting in oppression of their neighbour, their offerings would not be accepted.

We might regard sacrifice as a sort of enacted prayer, following a divinely-instituted pattern of approach. When performed in faith, as a petition to the Lord for cleansing, forgiveness, access, or communion, worshippers could be assured of the acceptance of their sacrifices.

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ On Mere Fidelity we have had the privilege of having Oliver O’Donovan, my favourite Christian ethicist and political theologian, as a guest on two of our last three episodes. Matt and I interviewed him on the subject of Christian Ethics and on Christian Politics. We also had Ewan Goligher, author of the recent How Should We Then Die? A Christian Response to Physician-Assisted Death, as a guest.

❧ The Theopolis Podcast’s Deuteronomy series continues, with episodes on Deuteronomy 25: Laws Concerning Levirate Marriage, Deuteronomy 25: Seized Private Parts and Just Weights, Deuteronomy 25: Remember What Amalek Did to You, and Deuteronomy 26: The Tithe and Praise of Yahweh.

❧ I have recently started a new series with Brent Siddall on the God’s Story Podcast. Having completed series on Daniel and Revelation, we are now tackling Zechariah. We now have episodes on chapter 1 and chapter 2.

❧ Pentecost is one of my favourite Christian feasts, yet widely downplayed. My friend Ben Miller joined me for two lengthy discussions of its significance and the doctrine of the Holy Spirit.

The first of our discussions is on Pentecost and the Gift of the Spirit.

The second is on the subject of Anticipations of Pentecost.

❧ In our previous Substack post, I had a lengthy reflection on the subject of the Internet as ‘Negative World’. I recorded myself reading the post for those who want to listen to it rather than read it.

❧ I have a piece in the latest issue of Plough magazine: Tech Cities of the Bible.

By the end of the seventh century BC, the Abrahamic alternative to Babel seemed to have failed, though, with Jewish exiles being taken in captivity back to the land of Babylon. The story of Daniel begins with this tragic return of Abraham’s offspring to the land of his origin. However, the careful reader of the Book of Daniel might notice familiar themes pervading it, variations of the ancient story of Babel.

The Book of Daniel is about the distant heirs of the Babel builders, of kings with ambitions for godhood, of attempts to bring all peoples under a single human power, of the frustration of language and interpretation, and of the downfall of great towers. In three successive chapters, the book describes three towering structures: the great statue in Nebuchadnezzar’s dream (Gen. 2), the golden statue of Nebuchadnezzar himself (Gen. 3), and the tree with the top reaching to heaven (Gen. 4). All three represent the empire’s attempt to subdue all things under it.

Susannah: And our Tech issue of the magazine is now out!

Upcoming Events

❧ We have a wedding in Boone, North Carolina in a fortnight’s time.

❧ Alastair will be speaking at the forthcoming Theopolis Ministry Conference on July 15th and 16th. Find out more about it here!

❧ Most of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Alastair and Susannah

Those discussions of Pentecost are ones I definitely plan to reflect on and re-listen to!