№ 46: The Collapse of Custom

Also a Copernican Revolution in theology and some Candlemas reflections

Alastair: I had been hoping that we would be able to publish a Substack post before Susannah went to Venice for Carnevale, but we had a lot on our plates, so it is slightly delayed. Our last post concluded with us arriving back in the UK at the end of January. February was—at least for me—largely a quiet month of work at home in Stoke. I have been writing, teaching my Psalms course, and enjoying the return to a regular routine.

We spent the morning of Friday 31st with a friend who is the rector of St Giles, a Church of England congregation in Newcastle-under-Lyme, a town adjacent to Stoke, within walking distance of our house. It was Susannah’s first time meeting him, and they also hit it off.

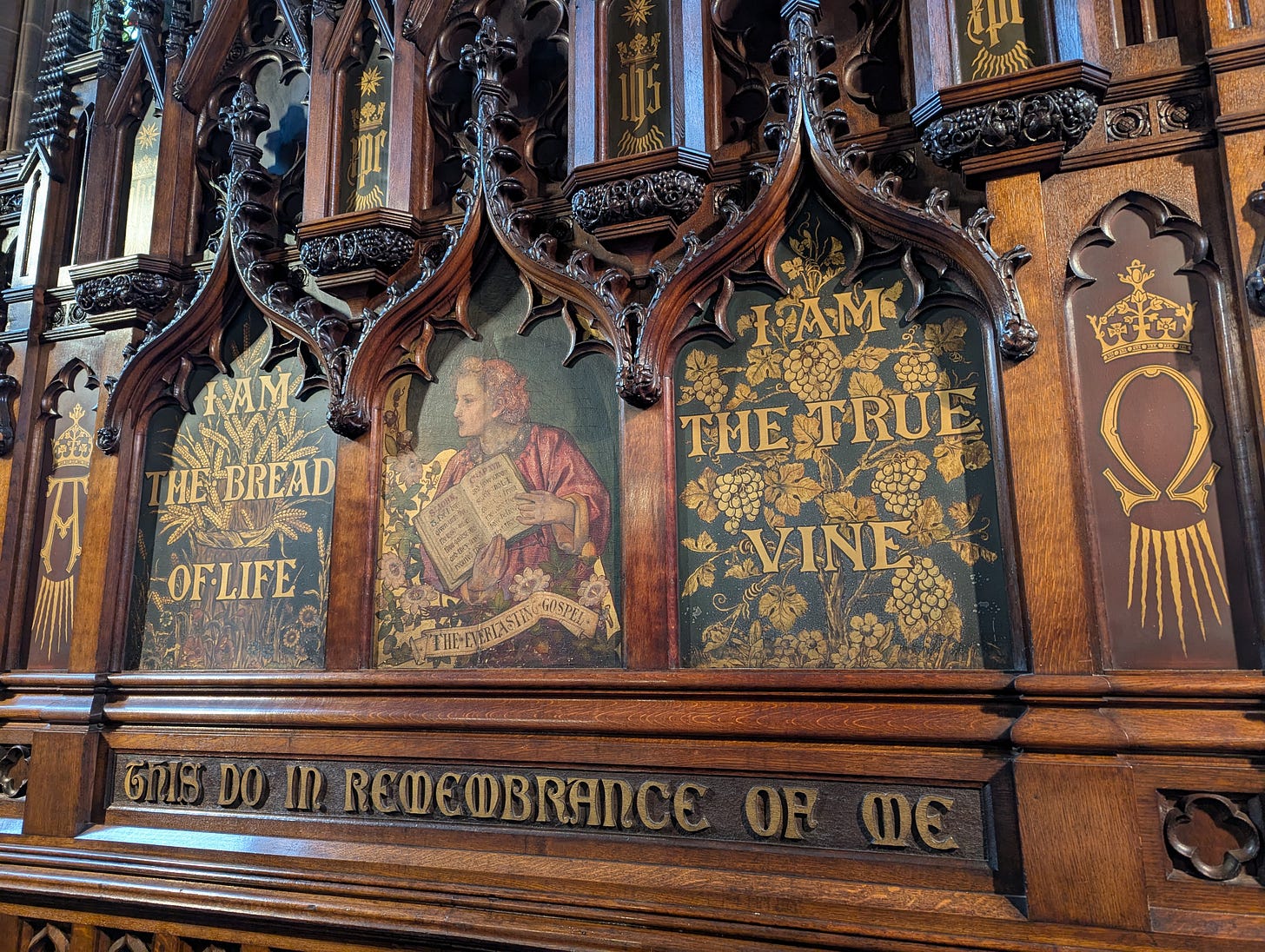

After coffee and breakfast, he gave us a tour of the church at which he ministers, telling us some of its fascinating, and at points rather amusing, history. In 1715, scandalized by the behaviour of the non-conformists, the good folk of St Giles set fire to the nearby Presbyterian church. Unfortunately, they were not the most careful arsonists and the fire carried to the roof of their own building. St Giles was rebuilt, but was poorly designed and needed to be replaced in the 1870s: the building is now in a Gothic Revival style, designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott.

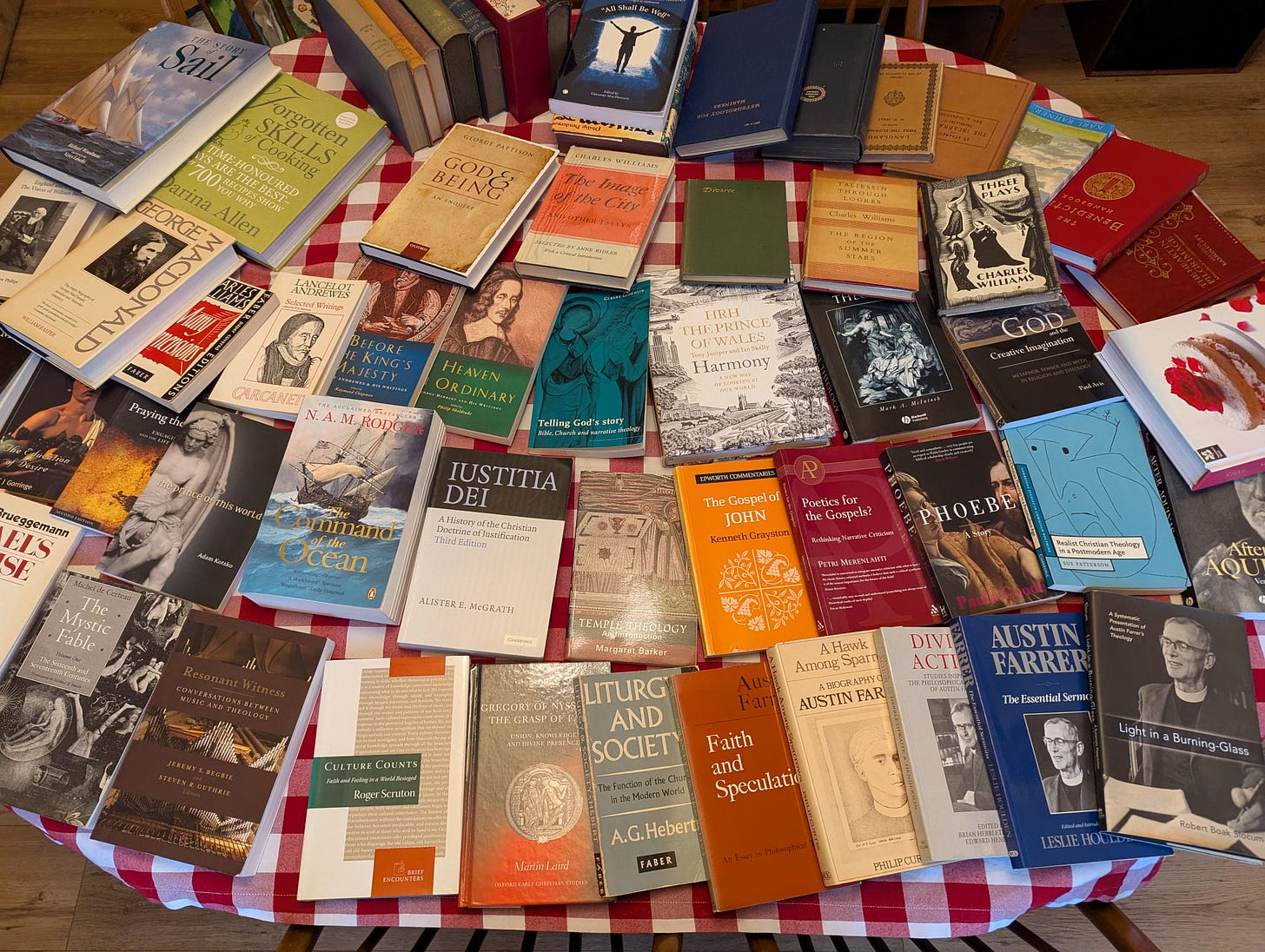

The next day, Susannah and I went out to the Alsager Book Emporium. We had been itching to go back there. An Anglo-Catholic man from the South of England had donated a large library, a treasure trove of volumes on literature, Anglican theology, and history. They had not yet been sorted and priced, and we were privileged to be allowed to trawl through numerous boxes of books in a shed. We ended up purchasing over fifty books between us, including lots of Austin Farrer and Charles Williams volumes, all for a small fraction of the price you would pay anywhere else. We went back to the book emporium a few weeks later and picked up several more books, but this was probably one of the most rewarding visits I have ever had there.

After church on Sunday, we went over to my parents for a meal and enjoyed a walk around the lake nearby afterwards. The circuit of the lake is a short, flat, and very pleasant walk, ideal for my father’s wheelchair. Unfortunately, the towpath of the canal is less accessible.

The next Friday, we visited Trentham, as Susannah felt an urgent need to buy pink things. Susannah accumulating large quantities of pink objects and fabric—and also some pink fabrics—has been a theme for 2025 so far.

That Saturday, my brother Peter and his wife came down from Manchester to celebrate his birthday with us and my parents. We went out for a meal and then returned to our house for cake.

In January, I heard that Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World was going to be playing in the Prince Charles Cinema in London. Master and Commander is one of our favourite movies, so we were not going to miss an opportunity to see it on the big screen. We booked tickets for the showing and found cheap train tickets down for a visit for just over one day.

London is always exciting for Susannah, [Susannah: Condescending much?] but she was especially eager to continue her fabric-hunting. Arriving in the city, she made a beeline for Liberty, which is one of her favourite stores. We managed to make it out of there slightly sooner than I had feared we would, but Susannah then wanted to go to Fortnum and Masons. On the way we saw some of the farmers’ protests that were going on in the city at the time. From there it was on to Hatchard’s (the oldest bookstore in the UK).

After a few hours of shopping, I finally succeeded in persuading my wife to move on [Susannah: Raised eyebrow emoji], although it did help to have an incredibly powerful inducement. Having come down to London to watch Master and Commander, it seemed appropriate to make the most of the city’s maritime history, so we went to visit the Golden Hinde replica on St Mary Overie’s Dock, not far from Southwark Cathedral. Some of the lights on the ship were not working when we first arrived, so we had a meal and did some work in the nearby pub, returning an hour later.

The Golden Hinde was the galleon with which Sir Francis Drake circumnavigated the globe between 1577 and 1580, the first English vessel to do so. The reconstruction is amazing, and well worth a visit. We had visited the Andalucía, a replica sixteenth century Spanish galleon, on a London visit last year, but the special historical—and patriotic!—appeal of the Golden Hinde added much to the experience.

We had considered visiting the HMS Belfast afterwards and passed by the impressive Hays Galleria on the way. However, by the time we arrived at the HMS Belfast, they were closing, so we made our way to Trafalgar Square instead. It felt fitting to visit Nelson’s Column before the movie. We met up with some friends with whom we were watching the movie in The Admiralty pub. I ordered Trafalgar Pie. Again, it felt fitting.

I have had some very enjoyable moviegoing experiences in my life, but I think this one may be the greatest one to date. There was a large, spirited, and extremely male audience; Susannah was one of only a small handful of women in attendance. They roared “NO!” in response to Captain Jack Aubrey’s “Do you want to call that raggedy ass Napoleon your king?!” and cheered after his “This ship is England” speech. We could not have felt more exhilarated when we left the theatre. Before getting a taxi to the place where we were staying, we passed Trafalgar Square and paid our respects to Lord Nelson again. [Susannah: I have NEVER had a better time at a movie, and am now committed to doing a Rocky Horror style showing when we’re back in NYC, encouraging attendees to join in even more fully than they did in the theater, singing along with the chanteys, etc; I’ll also make hardtack and plum duff and so on, and encourage period clothing.]

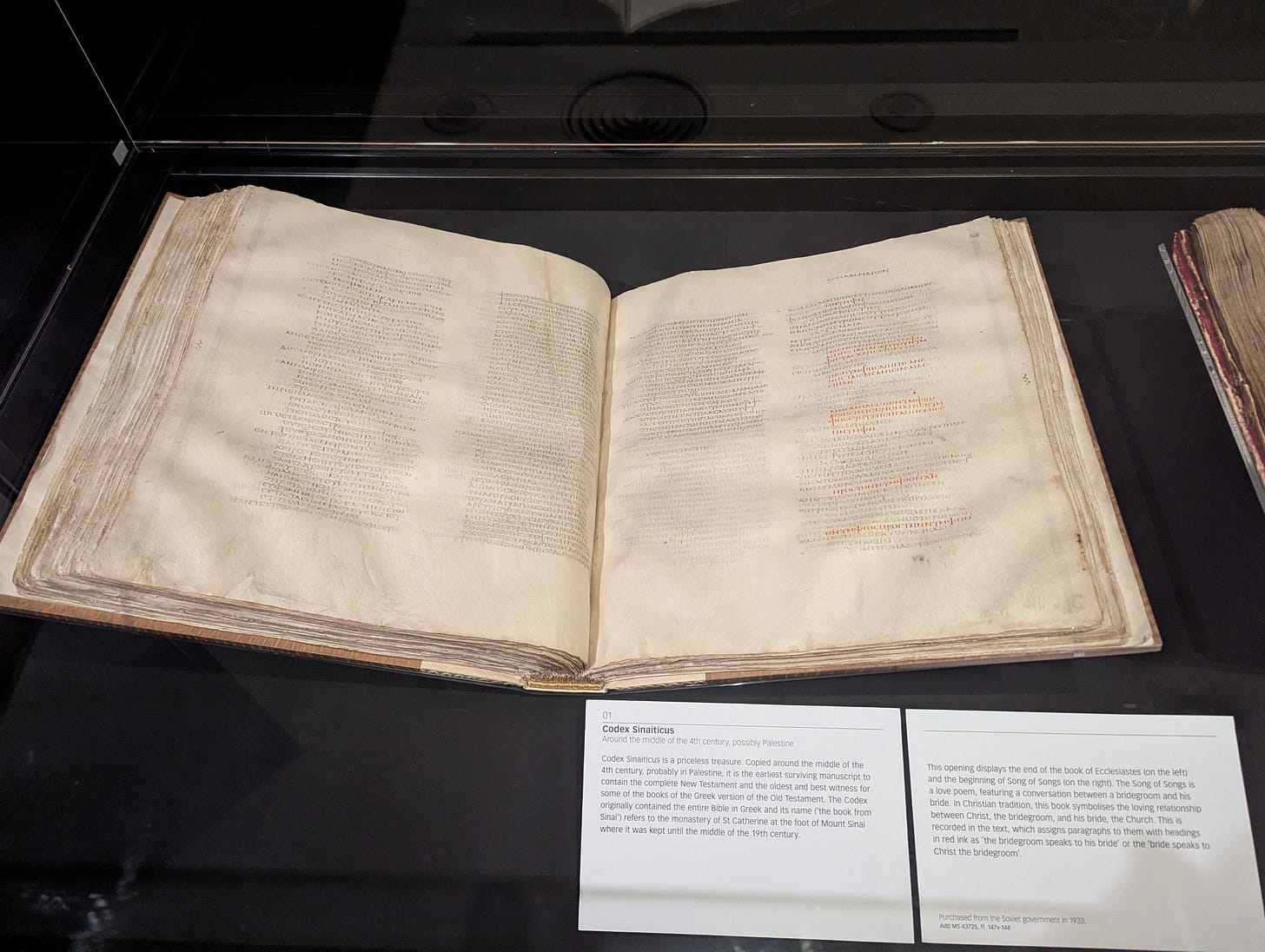

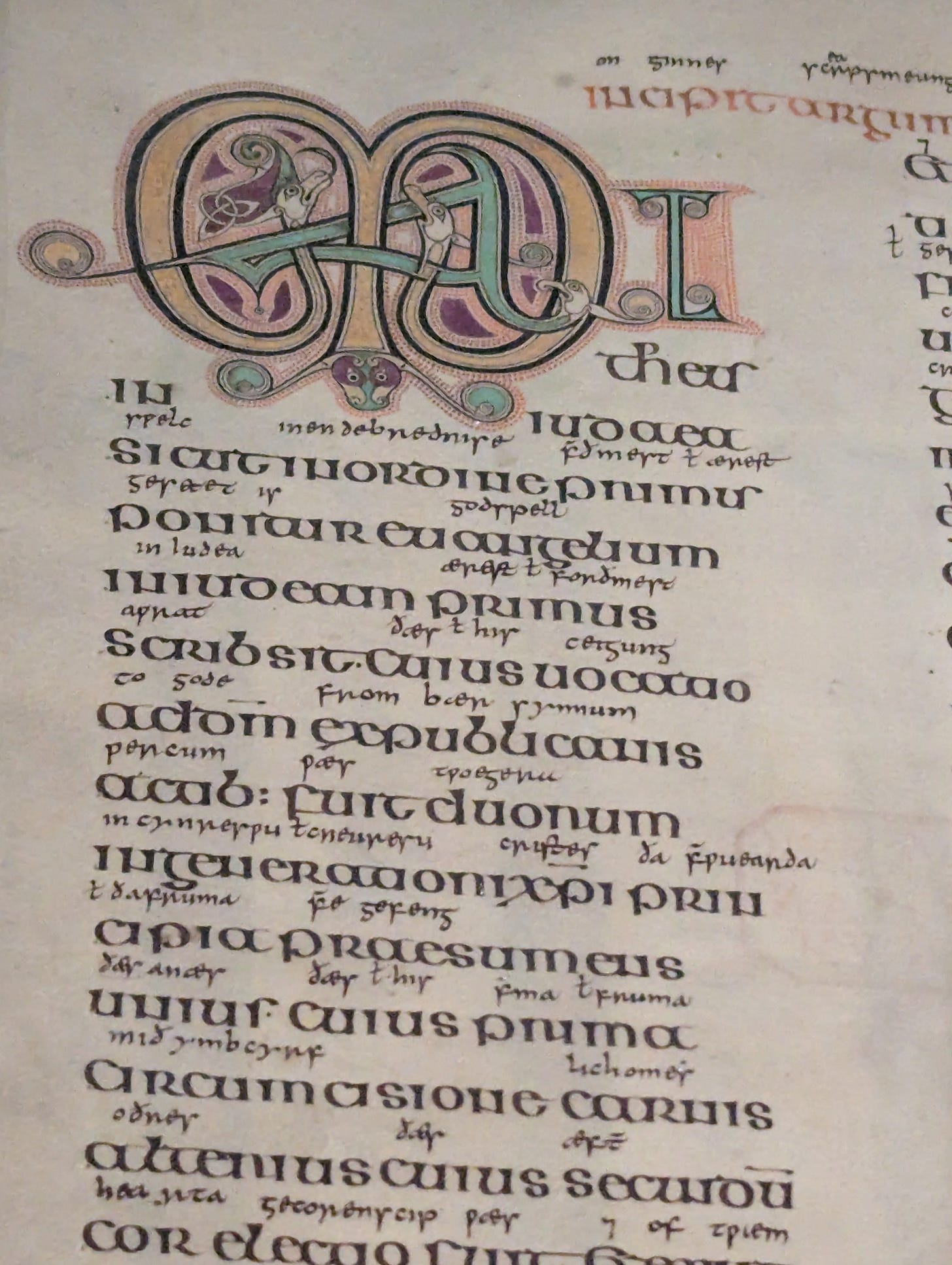

We had a few hours before our train from Euston the next morning, so, after a full English breakfast, we paid a visit to the British Library, which Susannah had not yet visited. Unfortunately, they were in the process of significant restoration work in their treasures section, so we did not get to see many of the books that we had come to see. We did, however, see the Lindisfarne Gospels, St Cuthbert’s Gospel, the Magna Carta, the Codex Sinaiticus, and a First Folio of Shakespeare, so we could not complain too much.

That Friday, which was also Valentine’s Day, we took a day trip up to Manchester to visit Peter and Fernanda. Manchester is only thirty-five minutes on the train, but, for some reason, we seldom make the trip. Every time we have visited Manchester, we have wondered why we do not do so more often.

We met up with Peter and Fernanda and had a full English breakfast in Brown’s, a delightful establishment, reminiscent of a Viennese café. Peter informed Susannah that there were huge fabric stores in the near vicinity, so there was no choice about what we were going to do next.

From there we went back to their house, where we renewed our acquaintance with their rabbits and watched the latest Wallace and Gromit movie together (highly recommended). Peter has often mentioned the hackspace he is involved with, yet I had never visited. He took me with him to it and showed me around, before producing a wooden candle stick for us on the lathe.

We then walked back towards the centre of Manchester, where we had coffee and cake together. After we were done, Susannah and I returned to Stoke, as I was teaching that evening.

The next week was quiet, punctuated only with time spent with my parents, another coffee with our rector friend, and another visit to Alsager. I preached that Sunday morning, my second sermon in the month. Susannah left for Venice on the Saturday.

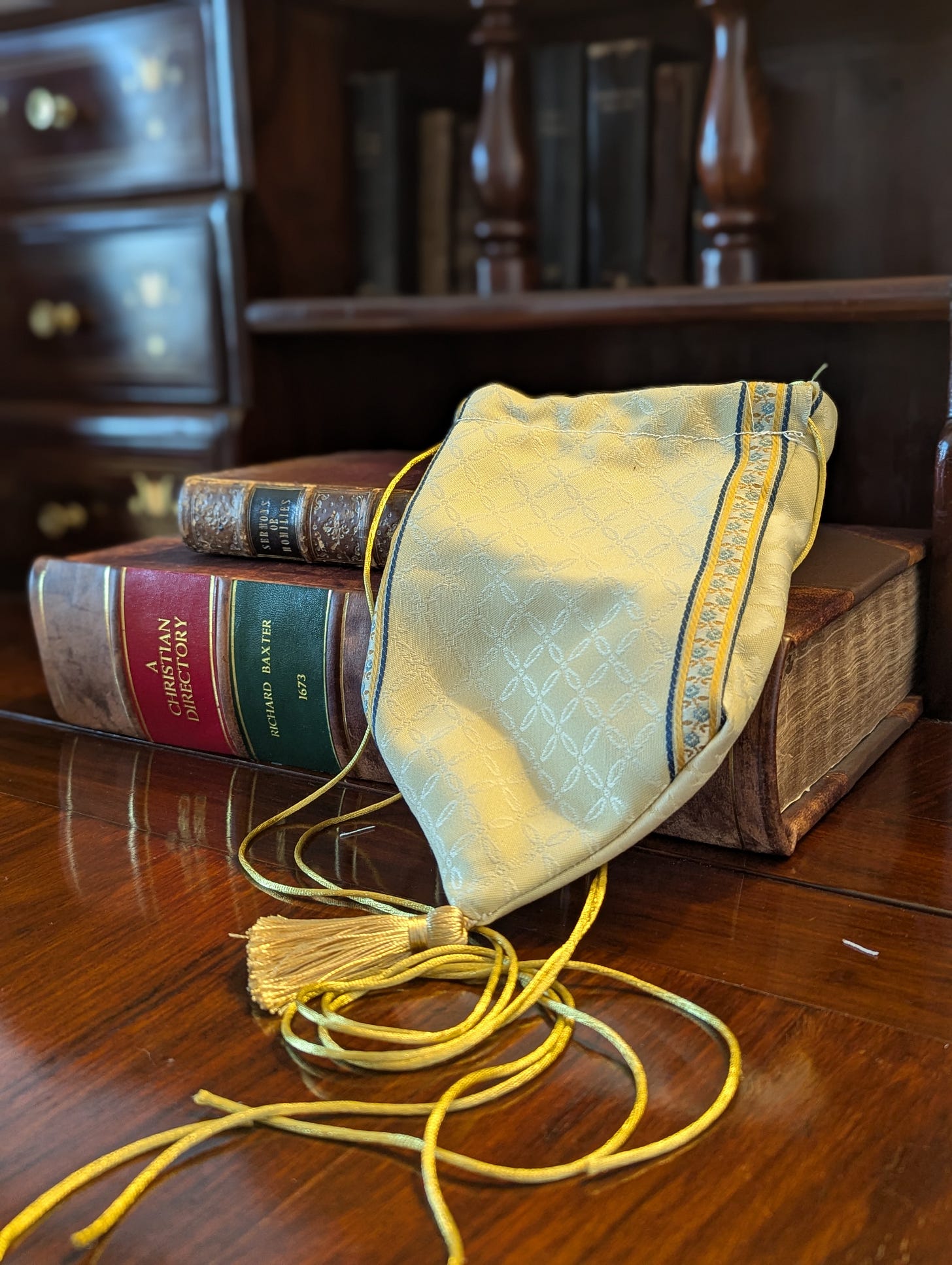

[Susannah: I also darted down to London once more - just for the night - on Wednesday, for a talk and dinner with Luke Bretherton, hosted by Jenny Sinclair, of Together for the Common Good; more about that below. I ALSO made enormous numbers of little brocade bags on my new sewing machine, which I brought to Venice to give to my Carnevale friends; see samples below.]

Last week was also a mundane one here. The one highlight was a visit to the nearby lake with my parents. They now offer bicycles of various kinds for visitors to hire and cycle around the lake. I had never seen one before, but they had a bicycle that could carry a wheelchair on the front. I was able to cycle around the lake with my father, which was very special.

Some Candlemas Reflections

February 2nd was Candlemas, a feast celebrating the presentation of the infant Jesus in the temple. Luke 2, which gives an account of this event, is a rich passage.

As many commentators have noted, there are numerous allusions to 1 Samuel in Luke and Acts. The books of Samuel are about the dawn of the Davidic dynasty and, fittingly, in books about the long-awaited arrival of David’s greater Son, Luke and Acts frequently play off that background.

John the Baptist, like Samuel, is given to a barren mother in the context of events in the temple, and appointed to be a lifelong Nazirite (1 Samuel 1:11; Luke 1:15). Mary’s Magnificat in Luke 1:46-55 plays off Hannah’s prayer from 1 Samuel 2:1-10.

Luke also calls back to the language of 1 Samuel (2:21, 26, 3:19) to describe Jesus and John growing (Luke 1:80, 2:40). In the context of Luke, Anna is Hannah’s namesake and engaged in the same activity. Once again, the story of a miraculous birth heralds future deliverance.

This background will also be highlighted in Luke’s account of Pentecost in Acts, where the disciples, like Hannah, have their faithful speech mistaken for drunken raving by religious leaders who unwittingly show their own insensitivity to God’s word and their coming judgment.

On several occasions, Luke gives us ages and numbers. Anna’s age is significant. She is 84—7 times 12. As with the connected figures of the woman with the issue of blood for twelve years and Jairus’ 12-year-old daughter, she symbolizes Israel awaiting deliverance.

References to the Spirit’s presence and activity are fairly unevenly distributed through the gospel of Luke. Remarkably, apart from 10:21, the rare such references after chapter 4 all relate to the future gift of the Spirit at Pentecost.

However, the Spirit is everywhere in the opening chapters of the gospel (1:15, 35, 41, 67, 3:22, 4:1, 14, 18). Notably, 2:25-27 present Simeon as a man of the Spirit, referencing the Spirit three times in connection with him in Luke 2:25-27a:

Now there was a man in Jerusalem, whose name was Simeon, and this man was righteous and devout, waiting for the consolation of Israel, and the Holy Spirit was upon him. And it had been revealed to him by the Holy Spirit that he would not see death before he had seen the Lord’s Christ. And he came in the Spirit into the temple…

In Acts, references to the work and presence of the Spirit are everywhere, especially in connection with Pentecost. In many respects, the early chapters of Luke present us with some anticipatory Pentecosts, most notably the so-called ‘Marian Pentecost’ in 1:35 and Jesus’ Baptism.

And the angel answered her, “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; therefore the child to be born will be called holy—the Son of God.”

Simeon and Anna in the temple are an important third Pentecost-like event. Anna is continually in the temple worshiping and praying (Luke 2:37), which is also how the disciples are described in the run-up to Pentecost (Luke 24:53; Acts 1:14).

There is a symmetry between the Presentation and Ascension-Pentecost, of course. Forty days after his birth of Mary, Jesus ascends to and is presented in the temple. Forty days after his rebirth from the grave, Jesus ascends to the heavenly temple (Acts 1:3).

In the Presentation there is a mini-Pentecost. A faithful man and a woman—one of Luke’s several noteworthy male-female pairings—anticipate the male and female disciples who will later pray and await the Gift of the Spirit in the ten days between Ascension and Pentecost.

It is in the prophecy of Simeon that the significance of Christ for the Gentiles—a key truth of Pentecost—is first really declared. Simeon prophesies and Anna breaks forth into thanks to God, then speaking of Jesus ‘to all who were waiting for the redemption of Jerusalem.’

We might see in Pentecost a fulfilment of the sacrifices for the presentation of a newborn child in Leviticus 12. Typically there is a lamb offered as an ascension and a dove as a purification. Christ is the ascending Lamb, the Spirit the descending cleansing dove.

The importance of the event we consider and the figures we recall at Candlemas should not be missed. Simeon and Anna are figures from the former times of Israel’s longing for redemption, but also foretastes of the time when her sons and daughters would prophesy.

“Lord, now you are letting your servant depart in peace,

according to your word;

for my eyes have seen your salvation

that you have prepared in the presence of all peoples,

a light for revelation to the Gentiles,

and for glory to your people Israel.”

A Theological Copernican Revolution

We can speak about the sun rising in the east and sinking in the west, doing its circuit of the sky, coming out from behind the clouds, of it being warmer in the summer and colder in the winter, and perhaps of its being darkened in an eclipse. For many historically, these ways in which the sun appears to us on earth have been taken as providing a simple account of its reality: the sun is evidently a powerful heavenly body that moves relative to us, going around the earth.

The Copernican Revolution—the discovery that we orbit the sun, rather than the sun orbiting the earth—was a radical transformation in the way that people viewed both the earth and the sun. Rather than the sun primarily being relative to the earth, the earth is primarily relative to the sun. What appear to be changes in the sun are principally changes in the earth’s relation to the sun, the results of movements in our orbit, the earth’s turning on its axis, events within our atmosphere, or the moon blocking our view of the sun.

We continue to speak in the ways that we always have about the sun’s relation to the earth—such ways of speaking are entirely appropriate. However, we also recognize that these ways of speaking only take us so far. They are, in fact, badly erroneous if we press them beyond their proper limits. Indeed, were we to do so, we would end up with a profoundly inaccurate and misleading understanding of what the sun actually is, and how we stand relative to it.

The Copernican Revolution reveals the radical relativity and non-fixity of our earth-bound vantage point. What seem from our perspective to be marked changes in the behaviour, position, and appearance of the sun are, in fact, overwhelmingly changes on our side of the relationship. Of course, this does not alter the experienced reality of our profound dependence upon and relationship to the sun one bit. The Copernican Revolution did not stop the cycle of day and night, or that of the seasons. The heat of the sun was not cooled upon the discovery of heliocentrism, nor its light dimmed. Indeed, the Copernican Revolution more powerfully revealed to us our dependence upon the sun and its importance as a body in the heavens.

A similar Revolution occurred in the field of theology, as theologians throughout the history of the Church have recognized that, although our lived experience of God is appropriately navigated with language with that speaks as though God were responding to us, as we might respond to other persons, the uncreated living God, who made all things and depends on no creature for his being, does not stand relative to us, but we stand relative to him.

There is language in the Bible that speaks of God as if he had body parts, as if he changed his mind, as if he reacted to human actions, or as if he had passions and emotions like a human being. The great theologians of the Church have generally recognized that such language is meaningful, much as our language about the sun rising and setting. However, it can become dangerously misleading if it is pressed beyond its proper bounds. When that happens, we can end up with a very distorted conception of God, a God shrunken to the limits of our experiential horizons. Though much of this language is found in the Bible, they were careful to place bounds upon it, lest God be reduced to a idol on account of it.

Just as the sun did not stop shining when Nicolaus Copernicus discovered that the earth moved around the sun, rather than vice versa, the Church’s recognition that God does not stand relative to us as we stand relative to him did not diminish the reality of God’s love. It did not delegitimate all the biblical language about God, which describes God relative to our vantage point. However, it has served to humble theologians and to accentuate the exceeding greatness of the living God, teaching us that, while our human vantage point is real and important, God is not contained within our horizon. Much that might seem to be change in God is really the changing of our own shifting vantage point, horizons, and relation to him.

It is important to recognize that the movements of the earth do not occasion a change in the sun, and that our experiences of the cycle of day and night and the seasons concern our changeability, rather than that of the sun. So Classical Theism’s Copernican Revolution in the understanding of God helps us better understand biblical teaching concerning matters such as the wrath of God, not as concerning changes in him, but as changes in how we stand in relation to the unchanging living God of love.

Most Christians instinctively know that much of the biblical language about God involves bodily metaphor or other ways of speaking that should not be pressed beyond their bounds. Where the existence of such bounds are appreciated and the biblical language is understood within its proper frames, it is trustworthy language, language by which we can confidently live our lives. Pushed beyond those bounds, however, it can lead to confusion, error, and idolatry. As we grow in maturity, we should ideally grow into a fuller understanding of God’s exceeding greatness. Classical theism and its Copernican Revolution in our account of God is not a rejection of the Bible and its language about God, but a recognition of both the highly relative character of our vantage points and horizons and the ineffable constancy of the love of the living God.

[Such lines of thinking will obviously raise many further questions. The Copernican Revolution transformed our understanding of the sun’s relationship to us and changed what it meant to say things such as ‘our sun’. When talking about God’s relationship with humanity, it is only appropriate that such a Revolution should be met with some caution, lest central Christian truths be jettisoned with potentially idolatrous projections. Consequently, a lot of work needs to be done to provide a robust account of the relationship between God and humanity, and to ensure that the biblical witness is not emptied of its proper force. My friend Ryan Hurd is teaching a course on the subject of the emotions of God in the coming Davenant Hall term, if you would be interested in investigating these issues further.]

Collapse of Ludic Community and Loss of Custom

Custom has something of a ludic character: the character of a game. Any group that has been playing a game together for long enough will generally have accumulated several of their own unwritten rules and expectations. This also applies to repeated forms of interaction characteristic of a society. [Susannah: My family has its own Bridge customs, for example, and we also have a version of baseball that we play with a whiffle ball, the pitcher standing directly in front of the front door to our family house in Connecticut.]

Beyond observing the official rules, there are many less enforceable behaviours expected of participants in society, falling in the domain of custom. This would be something like what Ivan Illich termed ‘probity’, well-ordered, decent, decorous, and proper conduct.

Customs and the social observance and enforcement of them tend both to require and produce societies with much higher levels of mutual trust and understanding; people can expect much of others and know much that is expected of them without it needing to be stipulated or demanded.

Customs have a more organic character than laws, typically arising out of a society's natural interactions, developing and settling through repetition, until it becomes something expected and observed by all. On a small scale, we might think of a family’s Christmas customs here.

The development and continuation of customs requires relatively enduring and stable groups that are peacefully ‘playing out’ life together in relatively enduring and stable contexts. They are undermined by high levels of social flux and conflict.

My friend Joseph Minich has spoken about modernity as the simultaneous global renegotiation of all human custom [you could take a course with him on Philosophy as a Way of Life next term]. This renegotiation is largely downstream of transformed material factors—changes in transport and infrastructure, in communication, and production. In many ways, the result has been a radical thinning out of former stable communities of play.

Where people move around a lot and ways of life are rapidly changing due to new technologies, values, media, and other such factors, or there is more social conflict, the power of custom will swiftly diminish or collapse, its place taken either by formal law or autonomous choice.

Yet law and individual choice (even wise choice) have a very different character from custom and cannot really replace it. Law lacks its informality, flexibility, and element of playfulness. Choice lacks its capacity to communicate collective wisdom and its lesser binding nature.

For instance, in his book on gender, Illich describes the way that what he terms ‘vernacular gender’ used to function differently from local community to local community. Gender was not approached as some universal law, as a matter of individual choice or wisdom, as some dictate of our biology, as a divine command, or psychological theory. Rather, each society ‘played’ out gender in their own distinctive ‘vernacular’ manner.

This did not mean that there were not expectations. However, the expectations would be more akin to the expectations of observing the proper steps of a dance, or playing a family game according to the recognized family rules. And the ludic character of the activity meant that it was not a strong statement about the fundamental and unchanging natural order of things.

Writing in 1982, Illich observed:

While in North America, even in Quebec, gender has been laundered from tools, it still survives in the tools of many pockets of rural Europe, and in some places more than in others. Here, men use the scythe and women the sickle. There, both use a sickle, but there are two sickles, each of a different design; the handle and blade betray the gender. In Styria, for example, men’s sickles are clean-edged for cutting, and women’s are indented, curved, made for the gathering of stalks. Wiegelmann’s great inventory of peasant work reports hundreds of such stories for a confusing variety of places. In one valley in the Alps, both genders use the scythe, but she only to cut the fodder, and he for the rye. Here, only she touches the knives in the kitchen; there, both cut the bread, but one cuts down and away, and the other draws the blade toward the chest.

Almost everywhere, men plant grain. But in one area on the upper Danube, women harrow and sow, and that is the one place where men do not handle the seed stock. Animals are tied to gender, even more than plants. In one place, women feed cows but never the draught animals. Farther east, women milk cows that belong to the homestead, while the herd on the manor grounds is milked by men. Only a few hours’ walk away, the same job is done only by maids. Tenaciously, the ties between gender and tool have survived, while wars have destroyed cities as they swept over Europe, and economic growth has transformed rural life. In the midst of synthetic pesticides, combines, and TV, certain old tools have anachronistically preserved the trappings of gender.

Only the faintest traces of the old vernacular orders of gender remain, if any remain at all. Indeed, barely any memory of these orders and what it was like to inhabit them has come down to us.

I was recently put in mind of Illich’s discussion of gender when considering the phenomenon of waulking songs, traditional Gaelic folk songs that women would sing while preparing tweed. These songs are reminiscent of the sort of songs and rhymes you might hear young girls singing on a school playground while jumping rope or clapping. [Susannah: They are similar too to the sea chanteys that sailors sing to cadence their work.]

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, radical urbanization, the rise of the automobile, and the emergence of a mass society of common spectacle, the old ludic communities have been lost. In their place we have forms of society that are designed to operate according to uniform rational principle, where anyone can fit in anywhere in first world societies, without needing to learn any customs. The thinning out of society through the loss of stable communities of play produces an anomie in its members. Without a strong intermediating category of custom between law and choice much of our orientation has been lost.

It seems unlikely to me that any significant reversal of this will occur without radical changes in the sorts of material factors that gave rise to the situation in the first place.

Keep the Republic of Letters Human

Susannah: As I mentioned above, just before I left for Venice (about which, next time), I went briefly down to London for a talk and dinner with Luke Bretherton, late of Duke, recently appointed Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology at Christ Church, Oxford. Luke is a friend, and it was lovely to see him, as well as to see several others I had met at the Cambridge conference in December. The event was organized by the wonderful Jenny Sinclair, whose Together for the Common Good Foundation I’ve only recently found out about.

Luke’s talk was about commons of various kinds: paradigmatically, the common land that all members of a community - including those with no land of their own - were permitted to gather wood from/graze their animals on etc; one of the major changes in England in the 18th century was the legal inclosure of these lands: legal private titles were created by Parliament, and the private title sold to (usually) local large landowners. Each instance of inclosure had to be legislated separately, and there were thus 5,200 inclosure (or enclosure) acts passed in England between 1604 and 1914; the granddaddy of them, though, was the Inclosure Act of 1773, passed just in time to begin to raise money for what would be the American War and the Napoleonic Wars (very very expensive).

Of course not everyone was a voter, and voting rights were linked to land ownership, and so the process of political and legal disenfranchisement-cum-land grab was a bit of a vicious circle, until it was sort of interrupted by the Reform Bills which gradually enfranchised everyone (but didn’t give Englishmen back their common land).

Results: in 1786 there were c. 250,000 independent landowners in Great Britain; by the end of the Napoleonic Wars at the Treaty of Paris in 1815, there were around 32,000.

The story is way more complicated than this of course, and one thing to remember is that the other major thing that happened during this time is that many more ways of making money popped up besides the land-lording and farming that were the source of nearly all the wealth in the society before this transition. But still.

The debate over enclosing lands raged throughout the early modern period, spawning hundreds, thousands of pamphlets and essays and magazine articles: the fodder of the post-Renaissance Republic of Letters which stretched from London to New York and East to where I sit now, Venice, this hub of print culture; how many, participating in this debate, wrote as I write now from a coffeehouse off the Piazza San Marco? Though they would have written from Florian, 200 meters away from me, rather than from this building: a light-filled pavilion right by the Giardini Reale, the most Habsburg building in Venice, originally, I believe, built for the Empress Sisi in her endless attempts to avoid the Imperial court at Vienna. Now it is an Illy caffe, with a helpful if intermittent WiFi connection.

Back to London, two weeks ago. Bretherton talked about other kinds of enclosure too: most recently, he made the parallel with the use of the text and images on the internet by text-based and visual AIs. The idea of a “digital commons” has a long history, and while the parallels are a little fuzzy, there’s something there.

This tapped into something: listening to the talk was one of those brain-explody times, when you feel like you’re fitting more pieces together of an important puzzle. The pieces came together in something like this shape:

I’ve recently (see here and here) written (and podcasted - see here and here and here) a great deal about AI and the importance, in the face of technology of which it is claimed that it can do the human work of eg writing essays, of insisting on continuing to do that work ourselves. I’ve wanted to start what I’ve called the Stay Human Movement, along the lines of William Morris and John Ruskin’s Arts and Crafts movement, to assert and practice the good of making our own essays and novels. Others have picked up this idea as well. I find the whole business of people so excited about outsourcing their entire life experience of making and imagining and thinking and inventing baffling: it is a profound and horrible anti-humanism, an anti-Renaissance. Case in point: Shivon Zilis, the mother of four (for now) of Elon Musk’s children, recently tweeted that she was telling her son a story about a Cybertruck Firetruck, and he asked to see a picture of it, and she said “I can’t, it’s only in our imaginations,” and then she realized that she could just get Grok to make a picture of it. In response, someone excitedly suggested giving Grok prompts to make up bedtime stories for your child. Both of these things were described as being wonderful celebrations of the human imagination. Both are obviously the opposite.

But, I can imagine someone saying, so what? Ignore the fact that others are getting ChatGPT to come up with stories for their children, you go ahead and just write your own stories. Nothing’s stopping you.

What Luke’s talk did was make me realize why this is not enough: why we in fact do need a movement. Or rather, it helped me put language to what I knew. I should have realized before, because this is what I did my MA thesis on, practically.

Let’s stick with language, with words and essays and stories, rather than images. LLM AIs are trained on the words and stories and articles and books already on the internet. What that means is that they’re trained on, inter alia, all the fan fiction that girls (mostly) on Livejournal write during the 2000s, all the Wikipedia articles that guys (mostly) wrote and argued over for the last 20 years. It is enclosing those commons and then in a sense selling them, remixed, back to us. At what cost? At the cost of that thing which has turned out to be the commondity most valuable, because least flexible and most limited: our attention. The cost as well of the energy it takes to cool the huge servers that these LLMs run on – it is a very physical thing, this AI.

But there’s more. The girls who wrote the livejournal stories, the guys who wrote the wikipedia articles, all of us who blogged our way through the early years of the 21st century, were participating in something that is irreducibly social. And we knew it: I remember thinking, saying, that the blogosphere was the modern Republic of Letters. We were all pamphleteers in those days, and pamphleteers don’t write for themselves. They write as a participation in the body politic, they are engaging in that candid speech that is the hallmark of liberal learning and political engagement. And that too is a commons.

And that too requires protection from enclosure, and that is why one can’t just write by oneself in a coffeehouse. We need a movement. We need an anti-enclosure movement, a movement that is a revival of the Republic of Letters: a movement that encourages and challenges us to do the human things, to write the essays and pamphlets and the fanfiction and the light verse - and to do it together. We need the Stay Human Movement, and we will have it.

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ Our new Hebrews series on the Theopolis podcast is now well underway, with three further episodes: Returning to the Past (Hebrews 1:1-3, Part 2), The Supremacy of God's Son (Hebrews 1:5-14), A Warning Against Neglecting Salvation (Hebrews 2:1-10), and Perfect Through Suffering (Hebrews 2:8-13).

❧ Plough recently published a piece of mine on what it means to read Holy Scripture: ‘Warning: The Bible is Not Just a Book’.

In Jesus Christ the teaching of the word of God finds its goal: our devotion to the study of the word of Holy Scripture must be growth in devotion to him. In our practice of the word of God, we seek to encounter Jesus and to be transformed by his glory. We seek to deepen our delight in and love of him. We find in him the perfect model of the love by which the law is fulfilled. We seek to mature in Christlike wisdom and insight, seeing the world as God would have us see it. We seek to be faithful bearers of the authority of the word, speaking with a humble effectiveness and power as servants of Christ by his Spirit into our world. We practice the word of God so that Christ’s word might richly dwell within us and enliven us. We practice the word of God together, so that we might be more fully knit into the life of his body. True reading of Holy Scripture is a training in Christ, God’s word made flesh.

❧ My friends Christian Leithart and John Ahern joined me for a discussion of Josef Pieper’s seminal essay, ‘Leisure: The Basis of Culture’.

❧ The latest episodes of the Zechariah series on the God’s Story Podcast, on Zechariah 9 and Zechariah 10, have been published.

❧ The concluding two videos in my Theopolis series on reading Holy Scripture Christologically have now been published.

Christ as Hermeneutic

Cross, Resurrection, and Hermeneutics

❧ I and several other Theopolis teachers were interviewed by SDG Music Radio.

❧ I recorded a version of my recent article for Theopolis: ‘Pentecost and the Gift of a New Politics’.

Upcoming Events

❧ Much of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

❧ Alastair’s next Davenant Hall course, on Bible Reading Skills for Narrative Texts, is now open for registration. The course begins on April 7th.

Much love,

Alastair and Susannah

That Copernican Revolution metaphor is quite helpful, seems to really "fit". Would be interested in hearing more of your thoughts on classical theism!

Wotta great movie.

Here's Philomena on the Golden Hind.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p0634q44