№ 45: Epiphany

Lots of new creations. The dehumanizing tendencies of AI. Rethinking narrative frames. The gifts of the Magi.

Alastair: We are nearing the end of January and this is our first proper Substack post for the year (excluding our 2024 review post, published on January 1st). We had a quieter start to the year, spending New Year’s Eve together at home and most of the week and a half that followed working from home.

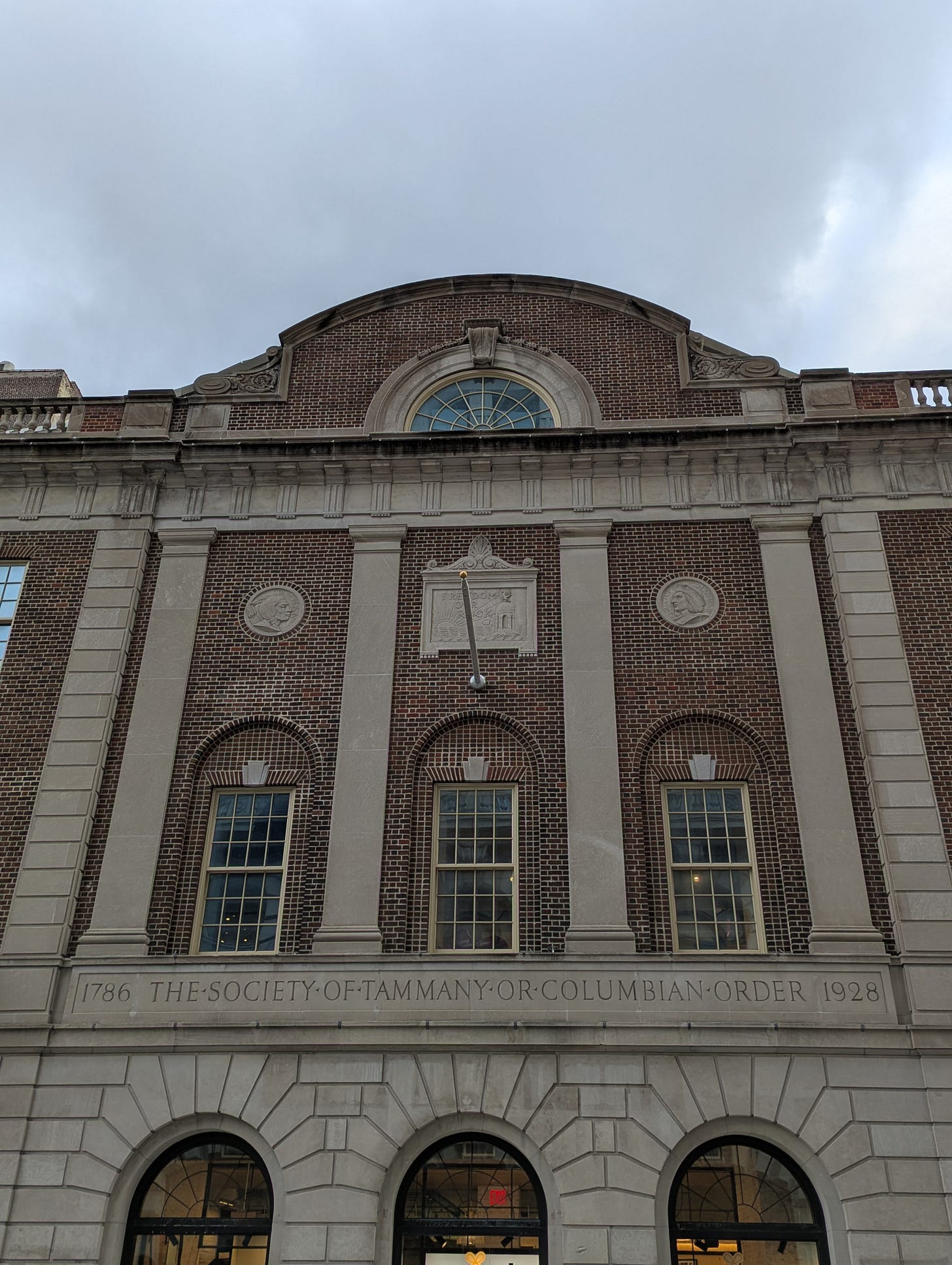

On New Year’s Day, we met up with Susannah’s father and stepmother for a meal in the city, after which we did some shopping, mostly for books, crafting supplies, and assorted ‘pink things’, which Susannah assured me she badly needed. [Susannah: Abruptly, just after Christmas, I became obsessed with rose-scented and colored things; I have no explanation for this but it has not abated.] A building caught my eye on the way back; on closer inspection it turned out to be the Tammany Hall building.

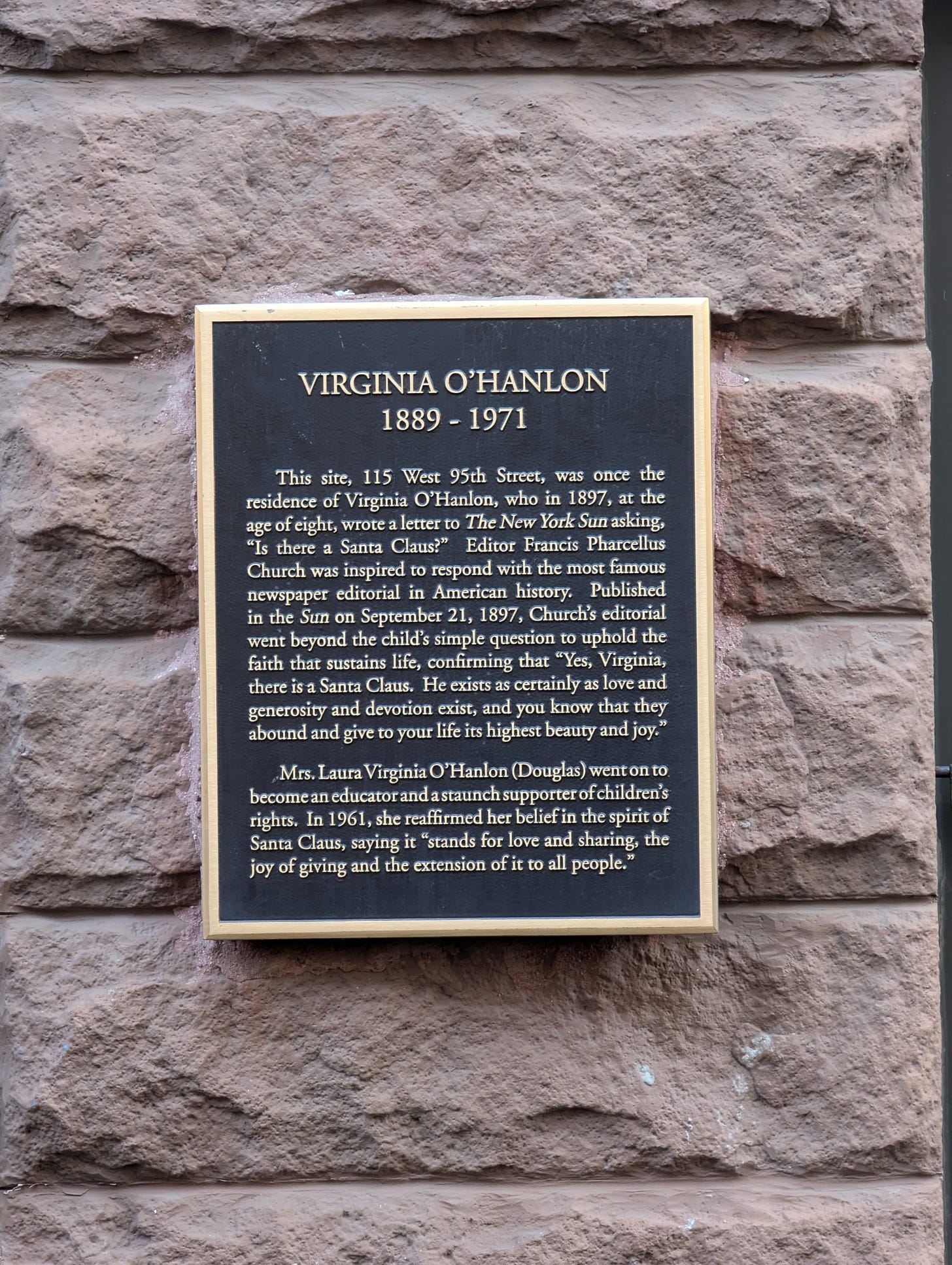

In another piece of New York City local history, this time Christmas-related, we came across the Virginia O’Hanlon plaque and letter in a window that we passed.

Besides baking an inordinate number of cookies, Susannah has been getting into sewing. For our first Christmas together, I bought her a sewing machine. Susannah had not used it and, on account of our moves, it had languished in storage for a few years. After several visits to our storage unit in search of it, she finally found it and brought it back to the apartment. Since then, she has been working on numerous projects. She also has plans for handcrafted items for some of our supporters. Watch this space!

Almost a year ago, I started one of the more challenging knitting projects that I have attempted to date: a steeked cardigan with colourwork. I had finished knitting the main body of it several months ago, but as I was daunted by the prospect of steeking it, had other projects on the go, and decided not to take it back with me to the UK, it was put to one side. I determined that, over the Christmas period, the time had come to finish it.

I suspect most people are unaware of what steeking involves—I did not know what it was myself until a year ago! For this sweater, it involved knitting the whole thing in the round, ensuring the tension of the colourwork was consistent throughout. The open front of the cardigan had to be made later.

If you look at the centre of the front, there is a five stitch strip disrupting the pattern of colours. That is the 'steek', where the cut would happen. First, it had to be reinforced on both sides of the cut with crocheted cords.

Having done that, Susannah added a couple of extra lines of sewing on both sides: belt and braces. I considered needle-felting the steek too, but changed my mind. I delayed the cut, first picking up a few hundred stitches and knitting the collar. I also added the pockets at this stage and started to sew up the loose ends.

Finally, I was ready to cut the garment right up the centre! The idea of cutting right up the middle of a piece you have been working on for months is terrifying to anticipate. But the actual process went very smoothly.

After this, all that was left to be done was to finish off the details. I sewed in the rest of the loose ends and added some buttons. The line of the cut steek naturally folds nicely into the garment and isn't under any tension on account of the collar. [Susannah: There’s a whole set of youtube videos and instructional pages and so on explaining how to do this; I would say half of each consists of emotional support for those who are about to cut a huge knitting project down the middle. ‘It’s okay, its really going to work, don’t worry,’ etc.]

We had several walks in the city over the next few days. We met up with one of Susannah’s good friends and her husband in Eataly. I had not met either of them before, but knew them from former online interactions. The next day we were invited for a meal with some dear friends from church, who introduced us to the game Spyfall.

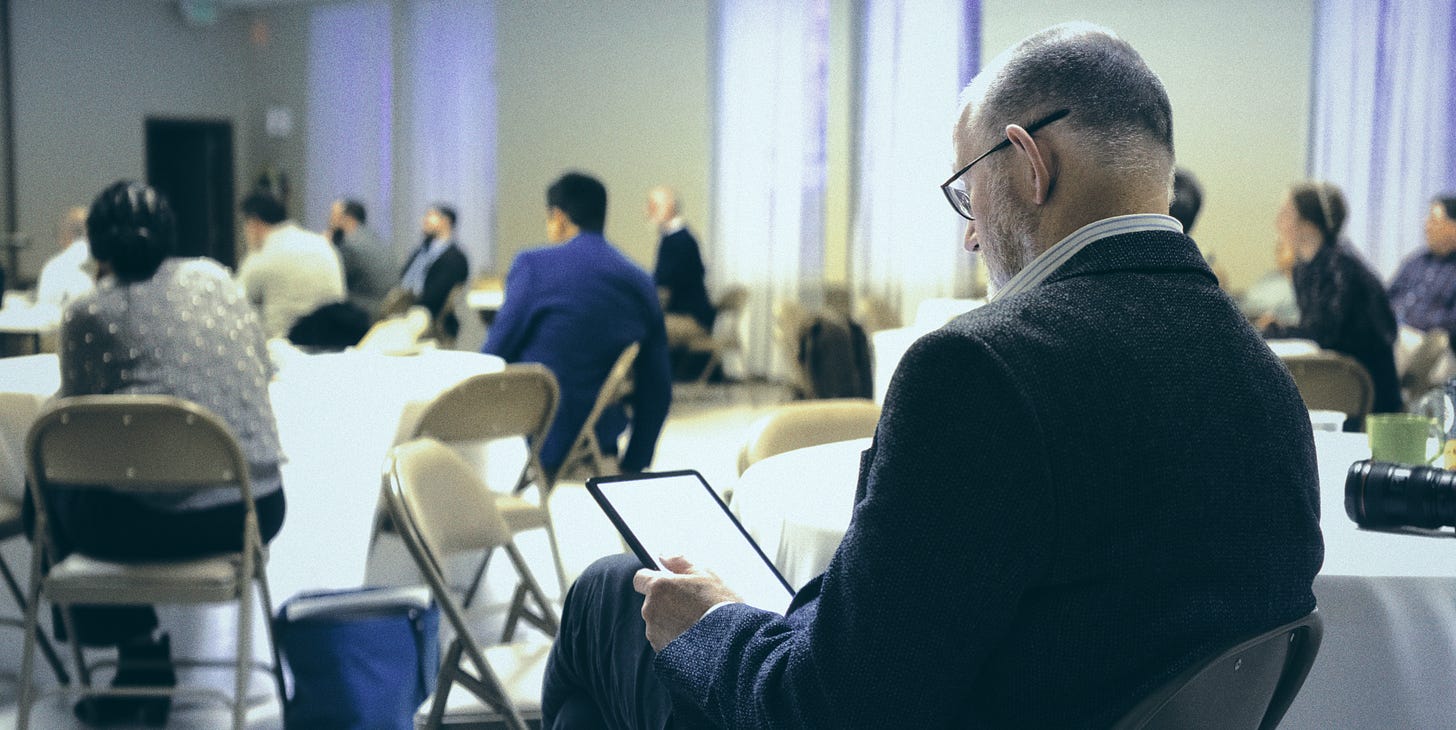

January is the Epiphany term of the Theopolis Fellows Program and, on the Sunday afternoon, I flew out to Birmingham, Alabama. This January was also the conclusion of the first Te Deum music program, which ran concurrently with the Fellows Program, under the oversight of Dr John Ahern.

I have described the Fellows Program on several occasions here before (see here and here, for instance). There are two residential terms, Trinity and Epiphany, Epiphany being the shorter of the two. Between the two there are fortnightly ‘Pesher groups’, during which we meet for around two and a half hours every Saturday morning to discuss biblical texts on which three groups of Fellows give presentations.

The residential periods of the Fellows Program are intense, with days full of instruction punctuated by three services of sung liturgy—matins, sext, and vespers. The evenings are filled with food and fellowship. Over the course of the week, students spend a lot of time interacting with faculty not merely in the formal teaching times, but in conversations over meals and other activities. There were also several babies and young children present at various points over the course of the week, which added to the atmosphere.

In the evenings, the Fellows often gathered on the porch of the house in which they were staying to sing together. We even had neighbours coming over, not to tell them to quieten down, but wanting to listen to them!

Since the addition of the Te Deum program, the number of students has increased and, with it, the quality of song. The inaugural Te Deum program was a huge success: John Ahern is a brilliant and engaging lecturer. He is also an accomplished musician and treated us to a number of postludes after vespers services. The Te Deum students added a different flavour to the week and, to crown its first year, two Te Deum students got engaged to each other.

Every time I attend the Fellows Program, I am reminded of the immense privilege it is to work alongside such gifted colleagues in service of a mission in which we all strongly believe. Everyone is brilliant in their own way, and invested in their work and in the students who attend. Likewise, the students are eager to make the most of their time, interact extensively with the faculty, and form deep friendships among themselves, which often outlast the program. If you are interested in finding out more about the Fellows Program you can do so here. You can find out about the Te Deum Music Fellows Program here.

I taught four hour-and-a-half classes on the subjects of Baptism, the Lord’s Supper, Liturgy and Work, and Liturgy, Ethics, and Politics. When not teaching, I was also able to get some writing done. I finished one article, wrote another from start to finish, and wrote a review. I recorded some videos for Theopolis. I also prepared for and taught the first class in my Psalms course.

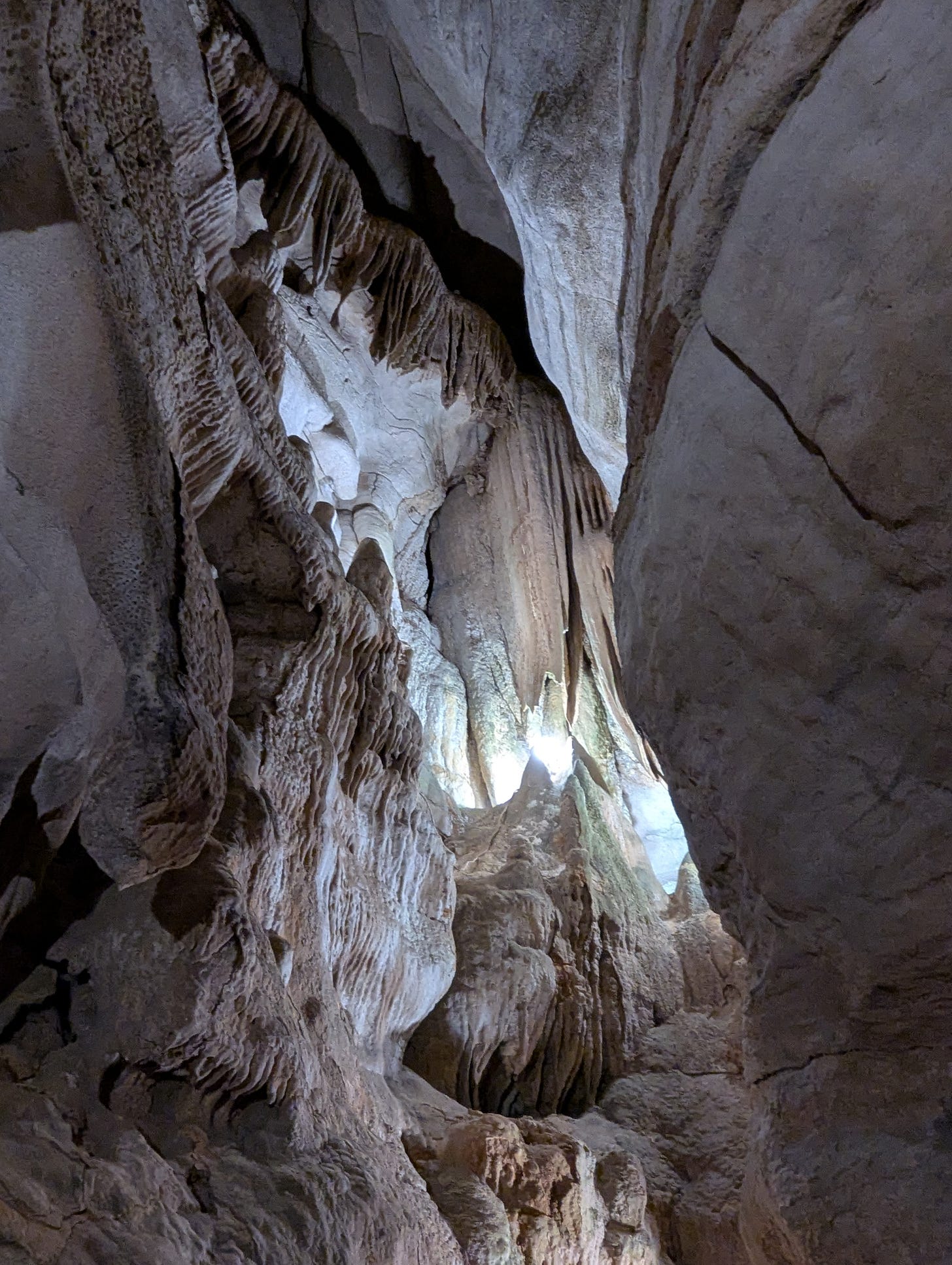

While most of the students and faculty returned home on the Saturday morning, I stayed on another day, visiting Rickwood Caverns State Park with a friend.

It had been some time since I last visited such caves and Rickwood Caverns were really spectacular. We saw a couple of bats in them too.

I attended Immanuel Reformed Church on Sunday and, after the fellowship meal following the service, went to the airport for my flight to Nashville. I was picked up from the airport by Nathan Johnson. We had a meal and then headed back to his house, where I stayed for the next couple of evenings.

On the Monday, we left early for New College Franklin, where I was spending the day. In the morning, I taught an hour-and-a-half class on Jesus and the Torah. Over the lunch period, I had a question and answer session. In the evening, after a meal with some of the faculty, I delivered the Collegium Lecture. It was followed by a panel discussion, audience questions, and lots of conversations over snacks.

I was labouring through a heavy cold the entire day and had had little sleep, so was running on fumes, but I made it through the day and greatly enjoyed it, despite my exhaustion. I was very impressed with New College, its faculty members, and its students. Several of them talked with me over the course of the day and I was impressed by how engaged and thoughtful they were.

The next morning, after a much fuller night’s sleep, I flew to New York City. The next day, I was leaving for the UK, so much of my time was spent sorting things out for the next couple of months. The next morning, before I was due to leave, I was recording a couple of episodes of the Theopolis Podcast. As I often do, I did some knitting, finishing up a large super chunky blanket that I had been working on for Susannah (she had wanted the colours, design, and extreme length—it is over six foot in length). Considering that I had started and finished knitting it in three weeks, I was very pleased, as was she when she received it!

I flew overnight back to the UK on Wednesday, arriving at around 7am in Manchester on the Thursday morning. I somehow made it through the day without sleeping, having not slept on the flight either. Fortunately, my cold was almost entirely gone.

Being back in Stoke-on-Trent is wonderful, especially as life will likely be slower for a month or so. The sale of our old house was also finalized on the Thursday morning, so it feels like an important transitional moment: my brothers and I owned the house for over twenty years. Susannah arrived back on Saturday afternoon.

I preached on Sunday morning and, in the afternoon, we visited my parents.

Susannah: Besides cookie baking and rose-colored objects and family things, the thing that I’ve been most consumed with over the last several weeks has been the question of AI. After several twitter rants about it, I was asked by three separate people to come on their podcasts to discuss it: first, I went on Thomas Mirus’ Catholic Culture podcast for a conversation focused on AI’s use in art, and then on Zack Graffman’s podcast—the link isn’t up yet; I’ll include it, and the third pod which has not yet been recorded, next time—for a conversation about AI more generally.

First, some caveats. I do think there are many good use cases for large language models. The deciphering of the Herculaneum scrolls, flash carbonized in the eruption of Vesuvius, would not be possible were it not for the technology behind ChatGPT; there are scientists working on cancer cures who are attempting to use AI to personalize medicine; others are using it to predict how proteins will fold and thus how they will interact with each other, a 50-year-old problem in biology. I can even imagine an LLM that will helpfully do boring data entry or complete bureaucratic tasks for you.

What I object to is the idea that we’ve gotten to a civilizational point where we humans are doing the boring bits while the AIs have taken over essay writing and portrait painting; this is simply an absurd prospect and one which I think all humans ought to rally together and reject. It was bad enough when some humans got to engage in the culture-making part of being human at the expense of others who had to work in the fields to buy their leisure; now we seem to be at the point where the AIs do the leisure activities and we have to scramble to find enough energy to allow them to carry this out.

Recently, Trump proposed that the American coal industry should be given subsidies in order to build enough plants to meet the energy needs of AI; again, all of this seems to simply stand the human telos, and even the telos of coal, on its head. “Won’t you consider the poor beleagured coal industry?” No I will not. If the coal industry wants my allegiance it has to be good for humans and the world in which we live [NB this is not going to happen], not good for AIs. “What will the AIs do if they can’t get enough energy to continue generating memes of the spirit of Shinzo Abe protecting Trump from the assassin’s bullet in response to prompts entered by terminally online 16-year-old boys?” This, sir, is not my concern. If young people want to make stupid memes they can do it the way we did in our youth: make them by hand using pixlr.

Of course, LLMs don’t actually do what we do when we write or make art or even when we try to investigate protein folding. There are no propositions, no logical connections, inside a LLM that allows it to “make an argument.” The programs that are lauded as having solved the protein-folding problem can predict, with mediocre accuracy which surely will improve, how a denatured protein will fold back up based on how similar proteins have done so, but, as has been pointed out, this does not so much solve the protein folding problem as evade it. The LLMs “reasoning” is opaque: this is because it doesn’t reason at all. There is no understanding; LLMs have not isolated “rules” for protein folding, or explained how or why denatured proteins can remember their original shapes. The mechanism is a black box, and we know for sure that there is nothing inside that black box.

My friend and fellow Upper West Sider David Schaengold has, in the pages of Plough, made the argument that the muddle in our thinking about AIs is downstream from the muddle in our thinking about computers in general. Of course computers can’t write essays or make arguments or be your friend: computers can’t even do math. Read the piece; it’s excellent.

In the same issue of the magazine, Arlie Coles, herself an LLM researcher and Episcopalian liturgy nerd, unleashes what is if anything even more of a jeremiad about the idea of using AI in the context of worship or sermon writing: this above all is disgraceful.

I’ve written in the Argosy before about the philosophical incoherence of “artificial intelligence.” What I want to argue here is that we must be on our guard against the predictable effect that the existence of such a technology will have on our views of ourselves, and on our own experience of the drive to create: to write, to make art. If the humanism of the Renaissance was a rediscovery of the excellences, the powers, of human beings, the dawn of AI is an anti-Renaissance, an anti-humanism. In the face of these machines that seem to do those things which are most characteristic of us, we must simply refuse to stop doing them ourselves. As I’ve argued before, what we need at the very least is a “stay human movement” patterned on the Arts & Crafts movement of William Morris and John Ruskin.

Related, although in a complex way: because I became so attached to my sewing machine in NYC, Alastair got me another one for the UK a couple of days ago—one that is sturdy enough to sew denim and canvas and sailcloth. Last night I got it up and running. I feel pretty fine about machine sewing, though not about machine embroidery; that’s where my inner May Morris pipes up disapprovingly.

Artificial Foolishness

Alastair: There is a failure condition of speech that becomes more apparent with the advent of artificial intelligence. Texts that can pass as the products of human beings can be generated with ‘artificial intelligence’ or procedurally, independent of any understanding or real thought. Reading such texts, one can often sense that there is something ‘off’ about them, even if it may be difficult to articulate exactly what it is. This sense is greatly heightened when one knows that it is a simulation of something we might once have regarded as a distinctively human product.

As we become more alert to the existence and the character of such uncanny texts, we should also start to recognize the degree to which their features can be shared with works commonly produced by human beings, revealing failures that can occur in our speech more generally.

There is a sort of speech that operates almost on autopilot, characterized by mindlessly imitative features and with impressions and behaviouristic responses substituting for attentive and careful interpretation. Such forms of speech can often seem reassuring, until we realize what is going on. They do not jolt us to attention with anything unexpected. The same buzzwords, clichés, expressions, tropes, rhetorical moves, turns of phrase, etc. are deployed, inviting a sort of mindless nodding along.

Caleb Smith recently reminded me of a 2012 piece on the Ribbonfarm blog entitled ‘Rediscovering Literacy’. Within it, Venkatesh Rao described the way that the figure he called the ‘Gollum’ related to speech. The Gollum, according to Rao, is ‘an archetype of an ordinary person turned into a ghost by consumer culture.’ As Rao characterized the Gollum, he is a figure who speaks behaviouristically and mechanically, mindlessly regurgitating undigested jargon. Such a figure can be highly educated, yet his education is a sort of advanced programming, rather than a formation in deep literacy, wisdom, understanding, and capacity for thought. Such persons can generate sophisticated texts, but language is largely not functioning as a means of true human thought for them.

Such derivative, near-automatic, imitative, predictable, tired, and increasingly meaningless speech is often a symptom of the abdication of critical thought that occurs within ideological movements. People can parrot the jargon, but could not carefully unpack and meaningfully expound upon it. Much of their speech is sophisticated deployment and manipulation of boilerplate ideological language. There is a complexity of procedure involved, exhibiting a sort of technical proficiency and raw aptitude for mental processing, yet little actual thought.

Although people might think chiefly of informal and mindless phatic speech in this connection, Rao has in mind people with advanced education. They are often doing something akin to the procedural generation and output of speech from specialized large language models upon which they have been trained. They may be doing something very sophisticated with language that would be out of reach for persons of average ‘intelligence’, but what they are doing is not thought. Such thoughtless speech fills academia, churches, politics, and many other areas, often being more pronounced at their very highest levels.

For instance, it is disappointing to see how few people think carefully about what they are doing with words and how their words relate to reality. Words and things have complex, variable, inconsistent, slippery, and unstable relationships between them. Consequently, we need to hold key words we use more lightly, and frequently return to the phenomena themselves. Many seem to struggle to use words to think carefully about reality, allowing words to do their ‘thinking’ for them instead.

Perhaps some of above average intelligence may be even more susceptible to this, especially those that fixate on definitions, logic, and system-building. Once a word has been attached as a label to some reality, the complex lineaments of the reality itself can be ignored and the label, now confused with the reality through an overidentification of words with things, can be subjected to forms of ‘logic’ divorced from reality. Such discourses are closed in upon themselves, games with words that are imposed upon reality, rather than open to it. Christian discourse is often not much better in this regard. Theological and other terms are insufficiently unsettled by constant testing against and study of the language of Scripture, or by carefully and repeatedly considering the shifting ways that they relate to extrascriptural realities.

Arresting the descent of our speech into such mindless habits takes effort. ‘Tabooing’ overused terms or pushing people to expound their meaning with incisive questioning, resisting abstractions, uncovering the underlying logic of an argument, ‘saying’ the same thing in a way that ‘sounds’ different all help. On account of its mimetic character, social media probably accelerates the descent of speech into thoughtlessly-generated and behaviouristically-processed discourse, so it is essential that we practice disciplines of thoughtful speech and reading.

If there is one good thing AI could do, it could alert us to how much of our speech is already a sort of AI sludge, something less than intelligence masquerading as it. Speech that can be produced without understanding is highly unlikely to be productive of much understanding.

In observing the AI-character of too much of our speech, I am put in mind of the book of Proverbs, which describes the contrast between the wise man and the fool at several points in terms of their contrasting manner of speech: the fool is described as having a sort of speech that is nearly automatic, whereas the wise weighs words in his heart and dispenses speech with circumspection and care. Proverbs 10:4 contrasts the ‘babbling’ of the fool with the wise man who receives commandments in his heart. The juxtaposition of the wise man who weighs and meditates upon words in his heart and the fool whose words reside merely upon unguarded and glib lips is also seen in verses like Proverbs 15:28—“The heart of the righteous ponders how to answer, but the mouth of the wicked pours out evil things.”

The words of the wise bubble up from the depths of their hearts like a spring of refreshing water:

The wise of heart is called discerning, and sweetness of speech increases persuasiveness. Good sense is a fountain of life to him who has it, but the instruction of fools is folly. The heart of the wise makes his speech judicious and adds persuasiveness to his lips. Gracious words are like a honeycomb, sweetness to the soul and health to the body. Proverbs 16:21-24

By contrast, the lips of fools function without the intervention of consideration, reflection, and moderation—“a fool’s lips walk into a fight, and his mouth invites a beating” (Proverbs 18:6). Lies flow naturally, automatically, and thoughtlessly from the mouths of liars: “a false witness breathes out lies” (Proverbs 14:5).

Much of the broader purpose of Holy Scripture—a point to which I often return—is about the internalization, embodiment, and humanization of speech. It is about the processes of contemplation, reflection, deliberation, memorization, creative and glorious performance, affective attunement, and inventive enaction whereby God’s words are metabolized into human life and community through the animating Spirit of Christ. The entirety of Scripture moves towards the Word becoming flesh.

AI may have a place (I am slightly less radical in my position on AI than Susannah is), but so many of its uses are a dehumanization and degradation of language itself—the most humanizing and elevating thing we possess—and the normalization of structurally ‘foolish’ speech. The fact that such foolish speech, not least in its complex and sophisticated forms, is already so prevalent in our society may make AI’s further erosion and diminishment of our language harder to discern and resist. There is, however, a small hope that, as we see sophisticated processes generating simulations of much human speech, we might start to apply more searching standards to speech in general.

Reworking our Narratives

We largely render, relate to, understand, and conceive of our actions within our worlds narratively. Without narratives, the world would be inscrutable, actions would lack meaning, and communities would not readily arise. Strong narratives provide strong conditions for other goods.

Consequently, people will often prefer strong narratives over weak ones, even at the cost of lesser fit to reality. What are some of the features of a strong narrative? Good versus evil. Heroes and villains. Sharply defined types of characters. Lack of complexity and obscurity. A close and clear relation between intentions and effects. Prioritization of courageous action. Being able to position oneself and/or one’s party as the main character. Archetypal resonance. Transplantability and scalability/universalizability: narrative frames that naturally slot onto new situations.

A ‘strong’ narrative frame means that you do not need to know the particulars of a new situation in great detail to be able to fit the various participants into your existing character types and sides, and render its dynamics in terms of your overarching plot and antagonisms.

The problem, unsurprisingly, is that reality is often not apt for strong narratives. Situations and the actors within them can be complex in ways that do not allow for sharply drawn characters or conflicts. They can have particular dynamics that do not fit archetypal frames.

One of the most consistent yet widely underconsidered fronts on which we encounter political tensions has to do with differing assumptions concerning conditions of narratability and our different approaches to our often automatic processes of narration.

One dimension of our approach to narrating our worlds is our preferred genres of narratives and the conceptual metaphors that accompany them. For instance, much tribal and ideological thought operates in terms of a highly simplistic martial root metaphor. There are good guys and bad guys. We need to defeat the bad guys. Problems are solved by raising sufficiently opposing force. The most essential thing is courage.

This has an understandable appeal. It imposes a very powerful narrative frame upon reality, in a way that excites and energizes agency. It grants absolute assurance in the moral justice of one’s cause. It gives people the cathartic thrill of participation in forceful action. It galvanizes a side. The lines are straightforward. [Susannah: And, to be sure, courage is a virtue.]

Now, there are contexts where there may be partial truths to such a conceptual frame. However, it can often obscure much more than it reveals. It tends to blind people to complicated systemic dynamics that drive dysfunctions. It limits people’s repertoire in response to evils.

Faced with people who criticize them and the measures that they advocate (even people who are opposed to the same evils), those operating within such a frame will simply cast them as enemies and attack them. There is little tolerance for dissent or questioning.

Faced with a great evil, people lurch into antagonistic mode and search for parties to fight against. Even when there are very worthy targets, the evils themselves will seldom be effectively addressed in such a manner. It is like taking a chainsaw to the task of bomb disposal.

The fighty frame largely excludes the tasks of careful reflection and deliberation. What looks like reflection and deliberation largely functions as rationalization for existing causes. People become impatient with the task of understanding and deliberation and rush to action.

And, even when there are key opponents to be overcome, the dominance of the conceptual framing of fighting tends to prevent people from counting costs, recognizing where force is going to be counterproductive and other means are required.

There is often a failure to recognize that, where force is needed, it must be more surgically focused and accompanied by very different modes of action to be effective for its ends. Dumb force can greatly empower one’s ‘enemies’ and exacerbate the problems you are tackling.

An alternative conceptual metaphor, if not one that is anywhere near as ‘strong’ narratively, might be provided by yarn. When yarn becomes tangled, not infrequently a tug or a cut is required. However, so much of the work of disentangling is a task of understanding—of tracing the tangled threads and perceiving the ways they are entwined. And, after the understanding, one must generally gradually and gently tease out threads, in order that your application of force on one thread might not create either a knot or unwanted unraveling elsewhere.

Faced with the tangled knotty mess of a social problem, those operating within narrow combative conceptual frames have a very limited repertoire to offer. Yet, due to the extreme moral self-confidence granted by their frame, mere recognition of genuine evil feels legitimating. Likewise, any who might hold them back from their highly combative measures will seem compromised by and/or complicit with those evils. Few recognize the heavy-lifting their conceptual framings are doing or the contestability and differing applicability of such frames.

Further, this comes with inability truly to understand the differing frames many other people are operating within, producing a stunted theory of mind. They cannot perceive others who share their concern to address evils but differ in frame, or to understand actual opponents. All too often, the result is a discourse that is loud, fighty, and dumb, approaches which routinely make situations worse by fighting fire with fire, prioritization of catharsis over effective action and speech, and pointless division and radicalization.

Once again, it is important to be mindful about what we are doing with our language in order to avoid, through a mindless use of it, it determining key aspects of our thinking for us.

The Gifts of Epiphany

The recent feast of Epiphany gave us occasion to think about the visit of the Magi to the infant Jesus.

The gifts of the Magi—gold, frankincense, and myrrh—should draw our minds back to several earlier passages in Scripture. In 1 Kings 10:23-25 and 2 Chronicles 9:22-24, at the height of Solomon's reign, we read of the kings of the earth bringing gifts to the Son of David (‘every one of them brought his present, articles of silver and hold, garments, myrrh, spices, horses, and mules’).

Solomon is also connected with imagery of gold, frankincense, and myrrh in the Song of Songs 3:6-10. There the palanquin of Solomon also evokes the wilderness tabernacle.

What is that coming up from the wilderness

like columns of smoke,

perfumed with myrrh and frankincense,

with all the fragrant powders of a merchant?

Behold, it is the litter of Solomon!

Around it are sixty mighty men,

some of the mighty men of Israel,

all of them wearing swords

and expert in war,

each with his sword at his thigh,

against terror by night.

King Solomon made himself a carriage

from the wood of Lebanon.

He made its posts of silver,

its back of gold, its seat of purple;

its interior was inlaid with love

by the daughters of Jerusalem.

The Song of Songs is also filled with imagery of gold, frankincense, and myrrh, presenting the lovers as glorious and delightful to each other.

Until the day breathes

and the shadows flee,

I will go away to the mountain of myrrh

and the hill of frankincense.Song of Songs 4:6

A garden locked is my sister, my bride,

a spring locked, a fountain sealed.

Your shoots are an orchard of pomegranates

with all choicest fruits,

henna with nard,

nard and saffron, calamus and cinnamon,

with all trees of frankincense,

myrrh and aloes,

with all choice spices—

a garden fountain, a well of living water,

and flowing streams from Lebanon.Song of Songs 4:12-15

The woman describes her lover as having a head like ‘the finest gold’, his arms as ‘rods of gold’, his legs as alabaster columns set on ‘bases of gold’, and his lips as lilies ‘dripping liquid myrrh’ (Song of Songs 5:10-16).

Moving into the prophetic literature, Isaiah 60:1-7 describes, with the appearance of a new light in the darkness of the nations, an influx of the treasures of the nations into Israel, for the glorification of the Lord's temple.

Arise, shine, for your light has come,

and the glory of the LORD has risen upon you.

For behold, darkness shall cover the earth,

and thick darkness the peoples;

but the LORD will arise upon you,

and his glory will be seen upon you.

And nations shall come to your light,

and kings to the brightness of your rising.Lift up your eyes all around, and see;

they all gather together, they come to you;

your sons shall come from afar,

and your daughters shall be carried on the hip.

Then you shall see and be radiant;

your heart shall thrill and exult,

because the abundance of the sea shall be turned to you,

the wealth of the nations shall come to you.

A multitude of camels shall cover you,

the young camels of Midian and Ephah;

all those from Sheba shall come.

They shall bring gold and frankincense,

and shall bring good news, the praises of the LORD.

All the flocks of Kedar shall be gathered to you;

the rams of Nebaioth shall minister to you;

they shall come up with acceptance on my altar,

and I will beautify my beautiful house.

Gold, frankincense, and myrrh are first associated with the tabernacle in Exodus 25-31. The gold was used for the central treasures of the house (the ark, mercy seat, table, lampstand, altar of incense). The myrrh was used for the anointing oil. The frankincense was used for the incense.

The Magi coming from afar, with those particular gifts, evokes a world of scriptural associations. Jesus is the glorious Son of David, the greater than Solomon, the King of kings, to whom the nations will come for wisdom and with tribute.

As the gifts of the Egyptians supplied materials for the tabernacle, King Hiram of Tyre gave cedar for Solomon's temple, King Cyrus of Persia gave gold and other treasures for the rebuilding of the temple, so the Magi represent a Gentile interest in and concern for the temple.

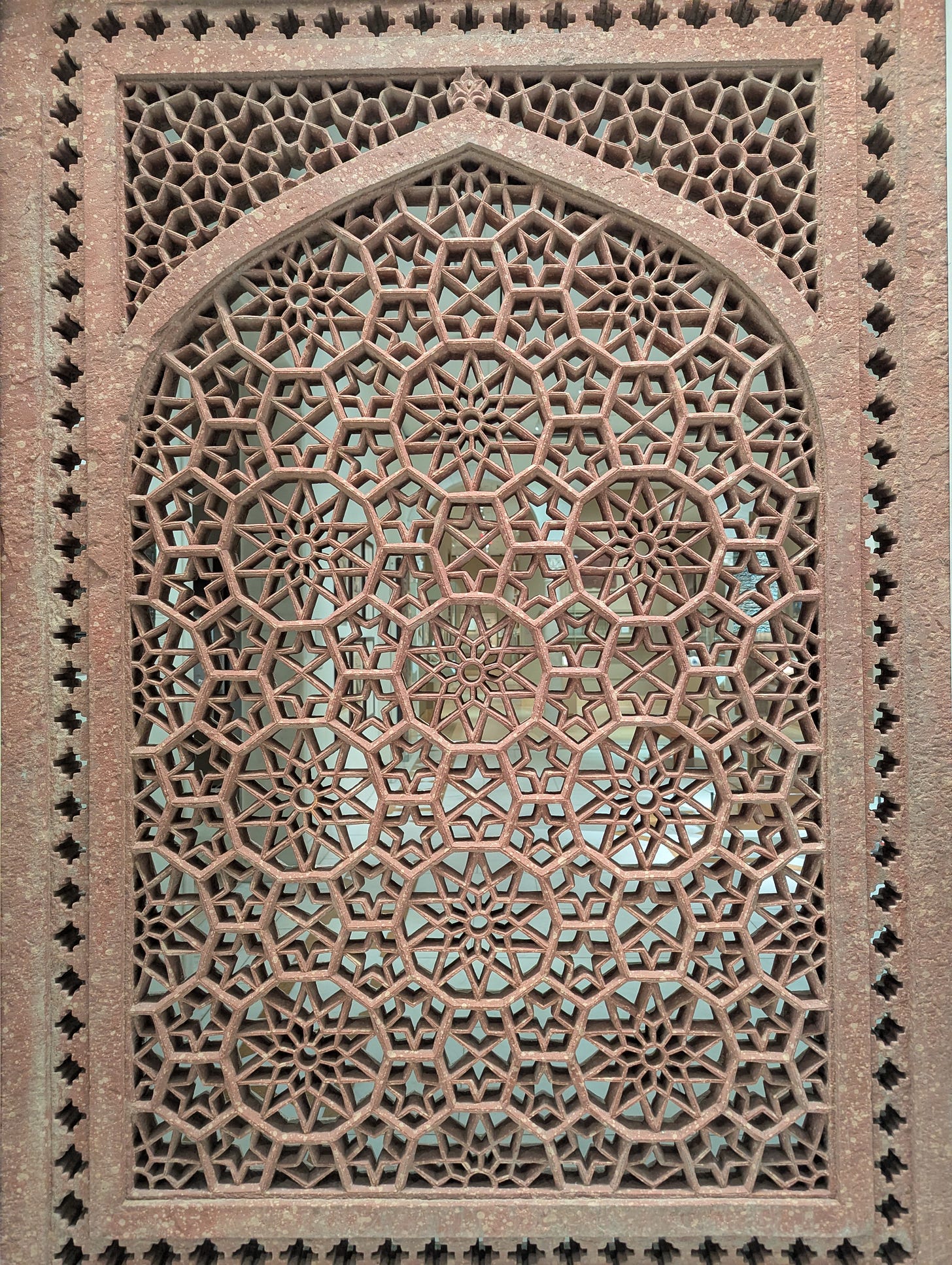

Jesus is eschatological light of Isaiah 60, to which the nations are drawn. He is the new temple or dwelling place of God—'God with us'—to which all peoples shall come with gifts to build it up and beautify it (Haggai 2:6-9).

Jesus is the great High Priest, anointed with myrrh, bearing incense in the golden throne room. We might also reflect upon these as sacred treasures, belonging to the sanctuary. Perhaps also reflect upon the opening of Christ's scented tomb as the unlocking of a treasure house.

Jesus is also the Bridegroom, who has come for his Bride, the answer to all longings, receiving the magnificent and wonderful treasures of rulers of the nations who have desired his appearance.

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ Having completed our epic Deuteronomy series, we had a question-and-answer episode on the Theopolis podcast. We have also started a new series, this time on the book of Hebrews. You can listen to the introductory episode here. We start our closer discussion of the text in the second episode: Hebrews 1:1-3.

❧ I produced a written version of my recent video for Mere Orthodoxy: ‘Did David Rape Bathsheba?: A Close Reading of the Relevant Texts’.

The books of Samuel are, among other things, a deep consideration of power and politics. One of its messages is that true power flourishes with virtue. Where virtue is lost, meaningful authority slips away with it. The events of the back half of the book of Samuel follow closely, in several ways (in direct cause and effect, in divine judgment, through others following David’s example, through the shift in the ethos of David’s court, etc.), from David’s seizing of Bathsheba.

The story of David and Bathsheba is not merely an isolated episode, but a precipitating event for the decline of David’s rule. I can think of few more powerful and sobering warnings of the destructive character and consequences of sin. It ruins lives and corrupts whole worlds.

❧ I reviewed Simon Kennedy’s new book, Against Worldview: Reimagining Christian Formation as Growth in Wisdom, on The Gospel Coalition website.

To heighten our sense of the distinctiveness of the Christian worldview and its oppositional relation with all others, we can also vastly overplay the degree to which our relation to reality is mediated by higher-level ideas. Common uses of the worldview concept can invite us to think of our relation to the world chiefly occurring through an all-encompassing theoretical gaze, a sort of ideological map of reality in its totality. Instead, Kennedy reminds us that our vantage point is limited, located in the hurly-burly of life and, as such, will always be a possible Christian worldview among others.

We aren’t chiefly students of such ideological maps in learning the lay of the land of reality. We’re explorers following partial itineraries and filling in gaps in our knowledge of a realm, or trackers with heightened senses attentive to our environment’s clues. Or, perhaps we’re hikers registering landmarks, finding their bearings, and navigating through varied terrain.

In the task of coming to grips with the often-hidden paths of creation, while we can genuinely find a greater grasp on the whole through the Christian faith, we’ll routinely find common cause with unbelievers. Kennedy’s welcome approach, which is also influenced by Charlotte Mason’s educational philosophy, brings Christian education back down to earth.

❧ Premier Christianity asked me to write about American evangelicals’ common support for Donald Trump, for British evangelicals for whom their American brothers and sisters’ politics are very foreign.

In contrast to the UK, white evangelicals are a large constituency in the US, with the potential to exercise an influential role in American politics, even if their lack of alternatives can make them a cheap date. However, there are wide variations in their regional distribution: while 52% of Tennessee’s population identifies as evangelical Protestant, for instance, only 10% of the state of New York does. In America’s established centres of cultural and political power, evangelicalism is typically very weak. While 43% of Americans identify as Protestant, only 6% of Harvard’s class of 2027 does.

As British evangelicals would likelier have a greater cultural proximity to New Yorkers than to Mississippians, figures like Tim Keller may feel much more relatable to us. That many of American evangelicalism’s most influential cultural institutions and figures have also been formed and operated in contexts where evangelicalism is a much smaller minority is an underconsidered source of tension within evangelicalism itself: ‘winsomeness’ as an evangelical posture is tailored more for minoritarian settings, whereas evangelicals in settings where they are the largest religious grouping or even a majority may desire a more assertive approach, presenting Christian faith as the rightful vehicle for their broader culture.

❧ While in Birmingham, I recorded a series of videos for Theopolis. Here is the first: Reading the Bible in Light of a Person (Part 1).

❧ I gave a lecture at New College Franklin, entitled ‘What it Means to be Male & Female: Clarifying Our Thinking About the Sexes’.

❧ My great friend and colleague Brad Littlejohn has just released a splendid new book, Called to Freedom: Retrieving Christian Liberty in an Age of License. I interviewed him about it on my podcast.

❧ I mention some of my favourite reads from 2024 in this brief piece for Theopolis.

❧ Since our last post, I have recorded the following reflections:

You Shall Call His Name Joshua

Our God Contracted to a Span

The Cosmos in a Tent

Symbolic History in the Gospels

Upcoming Events

❧ Much of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Alastair and Susannah

It's difficult for me to see AI as fundamentally different than any of the other historical tech monsters of the Id, none of which has done us in.

AI has demonstrated surprising results in helping students make progress, compared with human tutors:

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/bs3yj8vLDKNnoa95m/five-recent-ai-tutoring-studies

Of course, the garbage in/garbage out dynamic never goes away. If someone trains an LLM on Marcion, Servetus, Marx, Rosseau, and Dugin, they will get vain babble. But if they train it on Augustine, Calvin, Lewis, etc. it will provide helpful distillations.

There is always surprising grace in these dynamics. If AI results in increasing the noise to signal ratio of human knowledge, it really doesn't matter, because the human mind is finite and can only intake a measurable amount of information, good or bad. Humans have already stuffed their minds as full as possible of what they crave and seek. If someone has wasted days of their life reading Alexander Dugin, they can't waste 100% + 76% more of their life reading warmed-over AI regurgitations of Dugin.

A friend has a theory that the rise of sexbots can only help us win. The bestial man will waste his productive time and money developing and enervating himself with these devices, which removes him from productive competition with wisdom-loving people. People with low time preference will always win in the end.

This is part of what is going on it the Deuteronomic curse of foreigners rising higher and lending to natives, while natives go lower and become indebted to foreigners. Debt is a disciplinary form of bondage which those who become at ease in their affluence will undergo at the hands of those who are hard working and use their affluence for productivity rather than indulgent leisure.

And, let's say that Kingsnorth is right, and there is some kind of actual demon in AI. Well, wonder if it's a match for the Holy Spirit?