№ 40: Desacralizing and Evangelizing Politics

Also voting and tribalism—election season extravaganza!

Susannah: Since I CAN, I am hijacking the top of this substack to discuss the most important aspect of the past several weeks: My niece Oona. She is 20 months old, and she and my little brother and my sister-in-law came to spend around ten days here in NYC and in the family house in Connecticut, on the occasion of what may become a custom on the reunion off-years: a mini-reunion over Columbus Day/Indigenous People’s Day weekend.

She is very, very nearly at the point of sentences, but it’s mostly single words still— but she learns maybe 20 new words a day. Nothing is stopping her. You can practically see her brain soaking up language. It’s the absolute best. Some favorite words: “Cashie,” meaning castle/any structure that she builds or gets an adult to build for her, and “Noonie,” meaning New Book, which is what she says when you have finished reading one book to her and she wants another one. At one point she was trying to convince my mother, her grandmother, to brush her (Debby’s) teeth, but Debby had already brushed her teeth. She explained this to Oona: “I’ve already brushed my teeth thoroughly.”

“Thoroughly,” said Oona.

There are just no words that she is not capable of. She is a very powerful person.

We had a great reunion: around 34 of us, I think, at our max; we were only missing ten people. The baby and toddler contingent was considerable, with another one on the way: Oona met some of her cousins for the first time. The photograph we took looked a lot like the one that had been taken at the 1970 reunion—around the same number of people - but we are only 1 out of 5 of the sub-families who descend from that original group. I’m on the Reunion Planning Committee for next year’s full reunion, which will I think be around 90 people. Possibly more.

Highlights of the reunion included a survey of local beaver activity (a dam was washed away last year, draining a small pond not very far from us, but the beavers mended the dam and now the pond is back; they and several otters are now occupying the renewed pond and the area below it); splitting and stacking nearly three cords of wood; reading aloud to toddlers; and playing Phunball (a family adaptation of whiffle-ball with site specific rules). I also made a giant pot of bean soup, which was very successful. We—Toby and Langan and Oona and me and mom and several aunts and uncles—stayed on for a couple of days after the reunion, and one morning, a frenzy came upon us (much like the warp spasms said to have come upon the Vikings in their battles) and we decided that the kitchen MUST BE CHANGED. IMMEDIATELY.

The house was built in 1783, and the only modernization that I know of was two propane lamps that were put into the kitchen because kerosene lamps don’t give enough light for cooking, and one electrical line which we plug a fridge into. The fridge is old and disgusting, and the stove—also propane—hasn’t worked for years, and all the built in cabinetry is profoundly inefficient and had holes chewed in it by mice, and the sink is made of rusty iron with grout that no one alive has ever seen clean. Our handyman had found us a reclaimed 1940s style white enamel double sink, new-looking, which he was going to install. There was also talk of new shelving, and a new-old fridge and stove. And on Monday morning, we made the decision. We pulled out all the old cabinetry and burned a good deal of it, inhaling what were surely delicious lead paint fumes, and put all the kitchen goods and chattels on the back porch, where I sorted through them to pull out the nice bits and pieces—cast iron pots and so on. The nasty bits, like many old saucepans with no lids, and charred cookie sheets, I put into big contractor bags to be taken for scrap. It was all incredibly gratifying.

That was two weeks ago. This past weekend, a couple of us were back up at the house for the seasonal close-up. The madness came upon us again, and we pulled out the stove and the fridge and cleaned in every corner and pulled out all the nails that people had hammered in to walls over the years to hang pots on and scraped the walls and spackled as needed, and my uncle deployed this foam hole-filler called Great Stuff, and then we painted the whole joint with nice bright white semi-gloss.

It’s practically paradise now.

The handyman and maybe my cousin are going to design and build new cabinetry, and we’ve been researching new-old looking stoves and fridges. An interesting part of the process was when a giant chunk of the plaster fell off the wall while I was scraping pre-paint, and I kind of explored behind it to figure out what the construction was—it was real old lathe and plaster, with horsehair and other stuff as insulation, over what turned out to be an interior stone wall which was one side of the chimney, stone-built in the center of the house. I thwapped a lot of spackle into the hole and hoped for the best; we’ve rebuilt plenty of the plaster ceilings and walls (once we found an eighteenth century shoe in the living room ceiling), but I don’t think this one needs immediate re-plastering. Maybe next generation.

Anyway then I came home to an apartment with zero Oona in it, which was sad, but I always love the sense of going-back-to-New-York-after-Mystic-closeup, because it always implies lots of projects: pieces to write, and so on.

Alastair: Since our previous Substack, Susannah and I have been apart from each other: while Susannah has been with family in New England, I have been enjoying time with family in Ye Olde England. While both of us could be accused of being remiss in our duties to our in-laws right now, the fact that we have spared each other for so long is testament to how seriously we take them!

My life has been pleasantly routine for the most part over the last few weeks: I have been teaching, reading, writing books and articles, recording lots of podcasts and videos—all the usual things. I have several larger projects that are occupying a lot of my time at the moment, which has also been enjoyable.

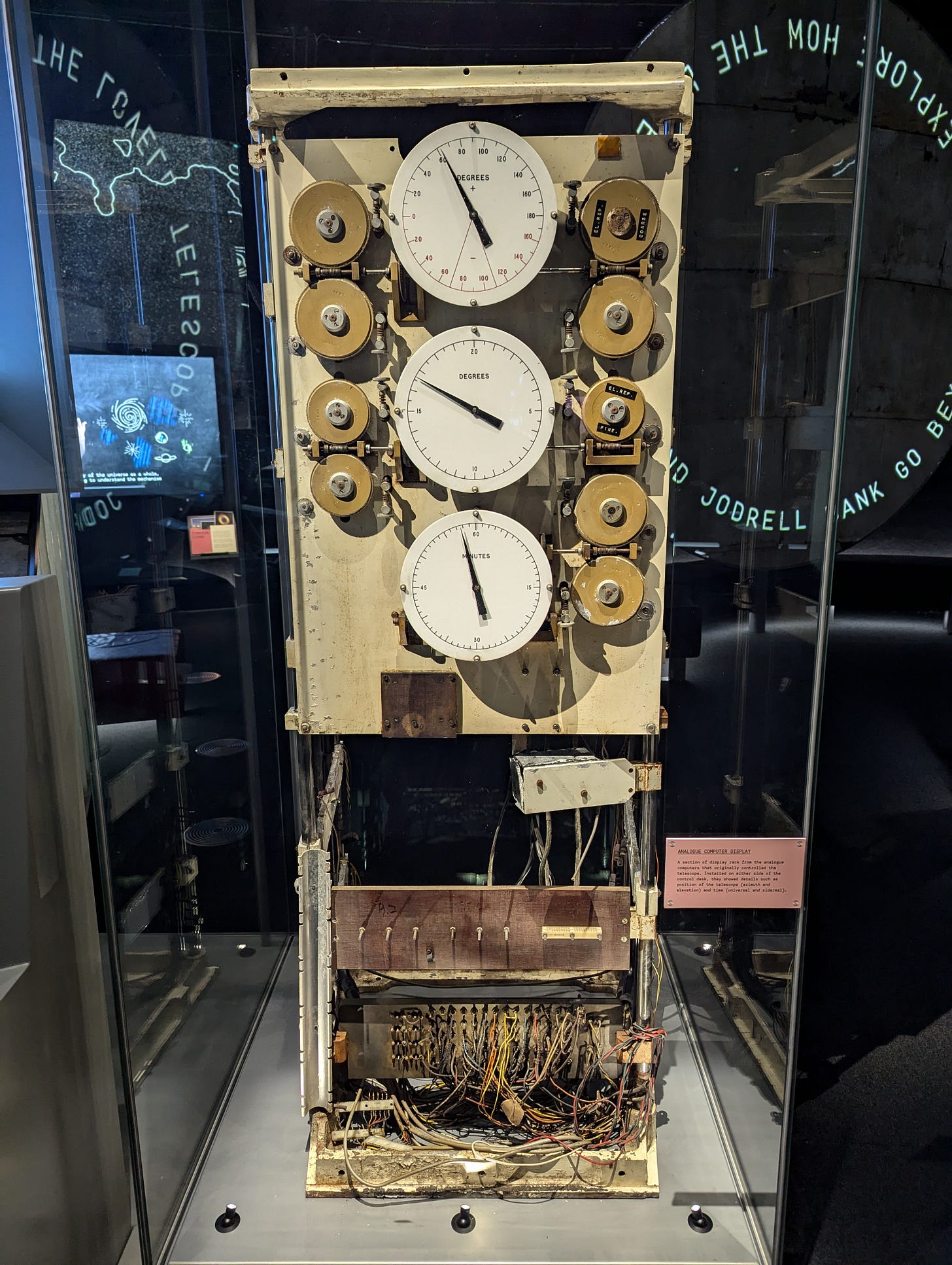

My brother and sister-in-law visited Stoke from Manchester and we went for an outing to Jodrell Bank with my parents, in celebration of my father’s birthday. Somehow I had never visited Jodrell Bank before, so it was all new to me.

Jodrell Bank is an observatory with the famous Lovell Telescope at its heart, the largest radio telescope at the time of its construction in 1957. It came online just in time to track Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite. Larger radio telescopes have subsequently been constructed, but it is still in the top three and remains in operation.

Jodrell Bank also provided the model for the Pharos Project, where the fourth Doctor Who struggled with the Master before falling and regenerating. The Lovell Telescope is awe-inspiring in its size and it is difficult to give a sense of its immense scale. It rotates on tracks at its base and can also be tilted to any position from the horizon to the zenith, so it can be directed towards any point in the sky.

It can be challenging to find suitable outings for my father nowadays, as he is very limited in how far he can travel and in his energy levels. However, our afternoon at Jodrell Bank went really well. We attended a dome show and also a talk about the telescope. We were impressed by the museums there too, which were engaging and interactive. Besides enjoying the site and exhibits, it was very special to go on such an outing with my parents and my brother and sister-in-law: such opportunities are increasingly rare.

My father had been eager for me to meet some of the Church of England ministers he knows in the area, so, just over a fortnight ago, he invited four of them over to their apartment in the retirement community and we got to know each other over a conversation about typology and the reading of Scripture. Even while extremely restricted in mobility and scope, my father remains concerned to find whatever outlet for ministry and connection with other Christians he can. He has led Bible studies in the retirement community and he and my mother seem to be very active among the Christians that live there. Having the time with the ministers was a real blessing for me too. There are some incredible people in the Stoke area, and it is always wonderful to get to know more of them.

While at Jodrell Bank, I had bought a jigsaw puzzle of the Periodic Table for my father and the next Saturday I cycled over to my parents and we spent a couple of hours putting it together.

Susannah is extremely possessive of the kitchen while she is around, so being alone in the house for over a month has given me occasion to cook again (fear not, Susannah, I have not just been ordering pizza!). Susannah is an incredible cook, so I do not miss cooking that much. However, it was good to be able to cook a meal for my parents, something I probably had not done for over a year.

About a fortnight ago, my uncle and aunt visited my parents for an afternoon. We had a meal together in Trentham and then looked around the gardens.

Trentham continues to be beautiful in the autumn. Once again, it was wonderful to have a day out with my parents, especially as my father seemed to be fairly well.

On the Saturday, I cycled out to my parents’ apartment to help my father with some computer issues and took a few minutes to look at the centre of Burslem. Burslem, the mother town of the Potteries, is largely a hollow shell of what it once was. However, looking around it one sees many indications of its former glory.

Perhaps my favourite building in the town is the old Wedgwood Institute. Unfortunately, the building now has broken windows, and extensive water damage, rot, and many further problems within. As things currently stand, while there are plans to prevent its condition deteriorating further, it is not going to be refurbished.

Last Wednesday, I walked to Newcastle-under-Lyme, where I met up with one of the ministers I had been introduced to by my father a couple of weeks before. We ended up chatting for the better part of three hours and plan to meet again soon.

On Thursday, a good friend of ours was passing through the area, en route from Glasgow to London, so I arranged to spend a few hours hanging out with her in Chester. Having met up at the station, we walked through the town to the Cathedral.

Although we had briefly glanced inside the Cathedral on my recent flying visit with Susannah, on that occasion we had not had the time to see much of the building. This time we were able to see a little more of it, including things such as the Lego Cathedral model and the consistory court.

We were quite impressed by the cloisters and by the ‘garth’ at its heart. A garth is a small garden enclosed by cloisters. Chester Cathedral’s garth contains Stephen Broadbent’s ‘Water of Life’ sculpture in a very pleasant setting.

From the cathedral we went to a pub for a meal, and then went up onto the city walls, planning to walk around the city. In the end, the route that we took was not as scenic as I had hoped, so we left the walls and visited the Roman gardens and the old Roman amphitheatre, before walking back through the town to the train station.

I have had several knitting projects that I have been working upon over the past few months. The largest of them is a huge throw, which I finally completed a few days ago. It is taller than I am. The final row was a picot bind off, which a long tassel that had to be knitted every three stitches, for a total of 720 stitches. That one row took over a ball and a half of wool. Having finished the binding off, I was rather concerned about what the process of blocking would involve, as the piece seemed pretty misshapen at first glance. Thankfully, though, I need not have worried: after soaking the piece in lukewarm water and stretching it out on several blankets, it readily assumed the desired shape.

It was my brother Mark’s fortieth birthday this summer and, to celebrate, he invited me and my brothers over to spend a week with him in Marseille. I am currently writing this from the South of France, where I have been enjoying time with my brothers Mark and Jonathan. In our next Substack post, I expect to tell you all about it!

Understanding the Boundaries Between Church and Politics

A couple of posts back, I discussed the importance of keeping faith both in and out of politics. In recent projects, I have had reason to revisit this issue from both sides, pushing strongly in both directions. In my series of Theopolis videos on Pentecostal politics (linked in this and our previous two posts), I presented a case for the inherently political character of the Christian faith and the capacity of the gift of the Spirit to renew our earthly polities and politics, whereas in my interview with Miles Smith and some of our recent Mere Fidelity episodes it was the dangers of a church entangled with partisan politics that were emphasized.

There is a delicate negotiation that needs to occur here, yet firm claims that need to be maintained on both sides. The integrity of both the church and the realm of ‘secular politics’—the politics of this present age—needs to be upheld. We cannot permit either the sacralization of secular politics, nor the politicization of the sacred. Likewise, the agencies of church and state both need to observe appropriate boundaries: the church should not ‘ecclesialize’ secular politics, nor should the state subordinate the church to its ends and its order.

However, the relationship between politics and faith and between state and Church is greatly complicated by the fact that, although we must retain the integrity and distinction of each, neither is autonomous nor without its constitutive relationship to the other. For instance, secular politics operates within an age and a realm that is framed and bounded by the gospel proclamation—‘Jesus is Lord’—and cannot operate as if it were an amoral enterprise. Such politics must be evangelized. Nor, for its part, is the Church and its message apolitical: at its very core, the Christian message concerns sovereignty and the establishment of a new political reality. The Church must resist both pietistic withdrawal and the sort of containment that would restrict its life to a privatized and depoliticized realm and its message to one of mere ‘spirituality’.

Yet the church also operates as a human and secular polity, under the oversight and governance of the rulers of this present age. Much of what churches do is not a matter of the authority proper to the gospel, but of the management of a temporary and temporal organization of this present age, concerning the manifold ‘externals’ that might be discussed in a church business meeting, for instance. In most of these affairs, the church is in some manner and to some degree or other under the authority of secular political authorities. The church cannot arrogate to itself political prerogatives that it has not been granted. Likewise, Christians are citizens and subjects in secular polities and must submit to and honour their rulers.

The Church must maintain something of a balance within itself. While any given church is situated in a particular locality, speaks a particular language, is composed of a particular people, and adheres to particular customs, it must also operate as a symbol of the universal and invisible Church. There are a variety of dangers here. The church could be tribalized, nationalized, or otherwise subordinated to some temporal identity that it exists to underwrite and/or sacralize. The church might also impose its own identity upon its context, immanentizing the eschaton and destroying temporal order. For instance, while the Church is a new family, it does not replace or efface our natural families. Christians may constitute a new holy nation, but we are also members of various earthly nations. The boundaries of membership of the Church must not be allowed to undermine the boundaries of membership of our earthly societies and polities.

The integrity of both sides must be maintained, as must a genuine interplay between the two. This is not a compartmentalization. The existence of a new holy nation, formed of people from all peoples and nations, is a reality that must transform the way that we relate to our own nations and to others. Although our earthly politics may appropriately focus on the proximate interests of our own people and governance of our own polities, the fact of the Church prevents us from absolutizing such a focus.

The realm of secular politics is also not purely autonomous and detached. The very age of the secular itself is bounded by the Lordship of Christ. The ruling authorities rule as ministers of Christ, established by his providence. Their authority ultimately derives from his and will one day be surrendered to him. The supposedly neutral and autonomous space of ‘secularism’ that claims to establish the terms of public life is a falsehood. Nor is politics an amoral task, to which Christian moral judgments and ethical insights have nothing authoritative to say.

Furthermore, as the gospel is received in a society, it cannot but transform the manner and the ends of its politics. The gospel message, the values it presents, the people it renovates, and the forms of life it produces will flow out like refreshing streams from the Church into the wider society. It was such a Pentecostal renewal of politics that I explored in my recent video series.

In my discussion with him, Miles Smith stressed the danger of meddlesome clericalism, where Christian ministers bind consciences or speak beyond both their calling and their competence on matters of political prudence. This is a persistent danger in some quarters, yet the pressure is not always coming from the top down. In many evangelical circles, perhaps largely on account of their more congregational form of polity, members of congregations will often be those who are most pushing for pastors to be explicitly political, to the point of treating this as a shibboleth of faithful ministry. This has been increasingly common over the past months, as many have been insisting, for instance, that their pastors come out more firmly for or against their preferred presidential candidate or political party.

Looking at the current state of Christian political discourse, especially in the US in the run-up to the election, one can see several different forms of failure to negotiate these tensions and relationships well. In most cases, people are recognizing certain aspects of the relationship that must be maintained, while neglecting others.

There are various forms of Christian Nationalism. In some forms, such as Stephen Wolfe’s, there is a strong insistence upon the grounding of politics in a nature that, practically speaking, is largely unaddressed by grace. The oft-repeated slogan, ‘grace does not destroy nature’, arguably functions to assert the immunity of natural politics to the transformation of grace and has the effect of putting a sort of ‘natural’ politics into overdrive. Within such a version of Christian Nationalism, a form of two kingdoms theology functions, beyond mere resistance to clericalism, largely to neutralize the gospel and the destabilizing presence of the Church in the actual work of politics. This version of Christian Nationalism tends to be hostile, not merely to conscience-binding in prudential political matters, but to the voice of the clergy, theologians, and ethicists in the realm of politics more generally. It chafes at the moral concerns that they raise, their theological challenge to the prominence granted to enmity in such politics, and their relativizing of the natural political frame. As such natural politics secures extensive autonomy for itself and operates largely under its own lights, it is at considerable risk of shrugging off Christian moral norms.

Practically speaking, however, the theological warrant that such a Christian Nationalism claims for its natural politics and the ostensibly Christian ends for which it is wielded can have an effect tantamount to sacralizing—rather than desacralizing—it. It is a politics in many respects made safe from Christianity, yet which claims Christianity as a warrant for itself. Such an approach rightly recognizes the importance of natural law for politics, along with some of the dangers of both clericalism and retreatist pietism. Nevertheless, its politics are deeply unevangelized.

In other cases, such as Doug Wilson’s version of Christian Nationalism, the clergy enjoy a privileged role, yet the church tends to be politicized and politics sacralized. Where someone like Wolfe draws an extra sharp line between the church and politics, Wilson tends to collapse distinct realms into each other. An aspect of this is the involvement of churches and their leaders in partisan political speech and the alignment of the church with particular constituencies, sacralizing their identity politics. Such an approach recognizes the value of Christian political involvement, dimensions of the inherently ‘political’ character of the Church’s existence, and the need for some sort of evangelization of political life, yet in ways that sacralize politics and wrongfully politicize the Church.

Another widespread way of dealing with the relationship is through pietistic withdrawal. In some cases, it seems that people operate in terms of the conviction that the Christian message is purely about ‘spiritual’ matters (‘my kingdom is not of this world’), has little or nothing to say to public and political life, and that Christians should largely be unconcerned with and uninvolved in political affairs. On occasions, the corrupt and sinful character of politics and political candidates is appealed to in order to discourage Christians from political activity. Politics, in this way of thinking, is profane, so must be avoided.

It is true that Christians should be profoundly alert to the sinfulness of much actual politics and politicians and the corrupting effect that this can have when we ‘put our trust in princes’, yet determined political activity need not entail such trust, nor a supposed ‘idolatry’ of power.

While this approach is alert to the corrupting effects of a sacralized politics and the necessity of maintaining our integrity, in many cases its faults actually results from its own form of sacralized politics, which does not adequately recognize that politics is both secular and fallen and engage in it accordingly. Although it appreciates the compromising effect of politics for many Christians, it fails to grant political activity its own integrity and to admit the possibility of determined political activity with no idolatry of power, and so approaches it with unreasonable expectations and demands.

Another, less common, danger might result from some form of ‘ecclesiocentrism’, which, privileging the Church, undermines natural order in various ways. The Church is truly the ‘family of God’ and we are brothers and sisters, but this must not be permitted to undermine natural families and their boundaries. The same holds for our polities. That other Christians are members of a new international body with us does not mean that differences of earthly nationality should cease to apply. However, ecclesiocentrics rightly appreciate that our political practice cannot operate as if the reality of the Church does not exist and that the Church is a new polity and people in the midst of the nations. The reality of the international body of the Church will relativize—without destroying—national identity and will frustrate many forms of nationalism.

Upholding both the distinction and the relationship between politics and the Church is of immense importance: so many key errors of our day result from problems in this area.

Not All of Life Should Be Worship

American evangelicalism is arguably often more of a culture than it is a theological movement or ecclesial body. An important feature of this is the minimal distance that it maintains between worship and everyday life.

This minimizing of the distance between worship and everyday life can be seen in things such as evangelicalism’s common valorization of spontaneity, ‘authenticity’, informality, folksiness, popular cultural forms, and other such things.

It tends to resist ritual, the setting apart of the realm of worship from the quotidian. It wants to be accessible, appealing, and familiar to whatever groups it desires to bring in. It is wary of churchliness that might be offputting to a first time visitor.

However, when such a posture is adopted, church and culture tend to get elided into each other.

Where the church and its worship ceases to be strange and to introduce a rupture into the everyday, culture can easily be sacralized in subtle and sometimes not so subtle ways. And where people find issues with the culture, it will be much easier to reject the entire amalgam.

Liturgy and church that unsettle the everyday, that force us to worship with lots of people with whom we wouldn't ordinarily socialize or identify, that involve rituals that are a little odd, for which we have norms of formal or festive clothing, etc. help to resist such absorption.

If we were to analogize the church and its worship with the garden sanctuary, and our wider weekday lives with the land beyond it, my point is that we need to remember that the garden was walled from the land and elevated above it.

Maintaining this division and boundary goes both ways and is a key part of the task of ministers. The ‘garden’ has to be able to distinguish itself from the ‘land’ and stand over against it, and the ‘land’ must have its own integrity too.

Evangelicalism tends to be weak here.

This, it should be noted, is a key issue when it comes to evangelicalism and politics. Politics gets sacralized and/or the sacred gets politicized far too easily. Faithful ministers need both to resist the politicization of the church and to resist a ‘ecclesialization’ of politics.

Complicating the Meaning of a Vote

There have been some good discussions of the ethics of voting recently. Something that is not sufficiently discussed is the coalitional character of much party politics, of the fact parties stand not merely for individual voters, but also have groups as stakeholders within them.

Voters are generally mindful, not merely of policies and candidates in the abstract, but of their groups’ political stakes and of the parties that recognize them. Much political activity also occurs within parties, as the interests of such groups often compete with others’.

Forsaking a party that has historically been receptive to one’s group's interests can be a very serious and costly step. The leverage and influence of such a group is much greater than of scattered individual voters, especially when other parties don’t offer an alternative home.

It seems to me that this a very common and even understandable part of most people’s political calculus, even though it is often neglected or ignored in discussions, and even though if can, if unchecked, cause problems: can be a source of corruption. For instance, it is entirely understandable that most white evangelicals would be GOP loyalists and Trump voters. That is the party that tries, at least partially, to convince them that it is where they belong. It appeals to them as an identity group. It is very difficult to say no to a party that says it is yours, on your side.

This does not mean that they are uncritical in this. They may reasonably believe that the danger of their group becoming politically homeless, without a recognized place in any coalition, means that it is much wiser to push for reform, reversal, or moderation from within.

[Susannah: Arguably, this is itself a corruption. To think of a political act as aiming at the good of one’s own interest group, whether that interest group is an identity-politics style group or not, is to act as a private person and not properly politically: political decisions ought to be motivated by care for the political common good, the justice and active peace and friendship that all those within a given society share with each other, rather than by a desire to promote the private interest of oneself or one’s group - the plebeians or the patricians in Classical Rome, for example; the Albizzi versus the Visconti in Renaissance Florence; Christians as an identity group as opposed to secular people in contemporary America. One can act politically “as a Christian,” but that would (ideally) mean that one acts politically as an imitator of Christ and as a sane and good human being, which means acting according to the political common good.]

Abstaining from voting, or going third party, carries genuine risks that much of your group’s political capital, stake, and leverage might be lost. Meanwhile, it is possible to retain group definition within a wider coalition and to disagree strongly with policies of your party (organizations such as Democrats for Life of America are an example of what this might look like for some pro-life voters, but also an illustration of some of the limitations of such approaches). Political activity in such cases will also typically exceed voting alone.

Consideration of such coalitional factors and group stakes and leverage is one reason why it is not unreasonable to be sympathetic to the political judgments of conservative black Protestant Democrat voters and to those of white evangelical Trump voters, even if you find their party or candidates highly objectionable in many respects.

The meaning of a vote is often quite complex, much more than people tend to acknowledge, and is certainly not constant between individual voters across polities, contexts, or groups. It need not be a straightforward sign of approval of a party, candidate, or raft of policies.

However, if there is one thing experience should have taught us, it is the dangers to which people taking such identity politics or interest group approaches expose themselves, and the ease with which principles and values can be dulled, diminished, or even jettisoned for the sake of political expediency. Without moral clarity, boundaries, candour, organization, and activity addressing issues with your party and its candidates, it is very easy to be corrupted and compromised. This is especially the case when you become tribal or narrowly fixated upon your political adversaries.

We should also recognize that differences in voting may not always involve differences of principle, or even of judgment, as the same considerations might lead to different people voting differently in the same election. Such recognition can make charity towards others easier. And such charity can also make common cause and appreciation of the diverse forms and contexts of faithful witness easier: such diversity is often necessary for the most effective action. There are committed Christians on both sides of the political aisle and in third parties.

And having Christians in these various positions can—like Obadiah and Elijah—help to spur and equip us for greater faithfulness. Third parties (groups like the American Solidarity Party, for instance) can clarify principle against the compromises concern for one’s group’s leverage can too easily result in.

Recognizing faithful Christians on the other side of the political aisle from ourselves can also discourage narrow tribalist instincts that undermine a quest for the common good. Collaboration with such persons can also produce more rounded and feasible policies.

None of this should or need come at the expense of clarity on issues of great moral import. However, in practice it so often has, which is probably why we need third parties and people willing to abstain from voting, even while mindful of the very real costs.

Tribalism

On several occasions, I have described movements like Christian Nationalism as ‘tribalist’ in many of their instincts and behaviours. The term ‘tribalist’ is widely employed by some as a pejorative for other persons with strong and unthinking in-group loyalty. A common objection is that such criticism is a cynical and hypocritical one—if the people making it were just honest, they would have to acknowledge they all have their own ‘tribes’! Everyone has some in-group, some circle of friends, some particular affinities or affections.

The following are a few rough thoughts on the subject. Before I begin, it is extremely important to recognize the distinction between my use of terms like ‘tribe’, ‘tribal’, or ‘cosmopolitan’ and terms like ‘tribalism’, ‘tribalist’, and ‘cosmopolitanism’. I use the latter terms to refer to a radicalization or absolutization of tendencies that, in a regular form, might be quite benign.

First, the word ‘tribe’ is not simply synonymous with ‘group’, ‘circle’, ‘network’, or ‘friends’. The term is not easily defined, but it is worth describing some of the features that are ‘family resemblances’ for groups to which this term might be applied, or features that led to its wider usage.

The term is largely adopted from older anthropological usage, where it refers to a very loosely defined class of societies. Such societies typically lack developed institutions, typically depend heavily on kinship and ethnic affinities, have a greater degree of homogeneity and solidarity than ‘more advanced’ societies, and generally have less formal and developed hierarchies. Importantly, they are one of the smallest social units that might enjoy considerable independence. While a family may be a social unit with strong solidarity, it almost invariably exists within a larger social order.

Historically, such groups have also been perceived as a more primitive form of political evolution as compared with a politics centered on chiefdoms, city-states, or nations. Understood against this background, ‘tribalism’ can refer to an atavistic tendency to shrink back from the challenge of living in societies with many differences to be traversed and negotiated into much narrower groups based upon ideological, social, ethnic, religious, or some other affinities.

A tribal way of thinking can also suggest a group that considers its identity and its good very much apart from—or even in opposition to—a wider society within which it has to work with groups with different identities, interests, and priorities. It can be more inward-looking, with a limited outlook beyond itself.

Tribal groups will often—by no means always—be male-dominated, characterized by a sort of martial honour culture, prioritizing loyalty and submission to the group, and have less hierarchical leadership.

One can see tribal tendencies, for instance, on the battlefield, where smaller groups of men can form intense bonds and a culture of loyalty and honour among themselves as they fight alongside each other. Although there will be some hierarchy at play, the sense of tribal unity will be felt among those fighting side-by-side, and not really with higher-ups who are not there in the trenches.

Such bonds can be especially attractive to many young men, granting them a sense of meaningful and purposeful belonging. Such a sense of tribalism is often enhanced through conflict, as an ‘us’ becomes clarified through antagonism with a ‘them’ and as camaraderie emerges through common cause.

Much of the contemporary move to new (primarily online) tribes is in response to the profound alienation that many, especially young men, feel in contemporary homogenized consumer culture. Tribes offer belonging, meaning, clarity, and purpose. And the real problems with tribalism should not simply be presumed to be worse than those of the deep cultural malaise against which tribalism typically reacts. Indeed, despite their serious faults, many forms of tribalism make certain real steps towards something healthier for those within them.

Second, in principle there is nothing wrong with being part of a tribe or having such a pattern of life. There are clear virtues to tribes. Sebastian Junger discusses some of the forgotten virtues and appeal of tribes in his stimulating if flawed book, Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging. In a fractured and alienating world of atomized individuals, the intense solidarity of novel forms of tribes and tribalism is considerable.

Third, as I said at the outset, being a member of a tribe is not the same as being a 'tribalist'. Tribalism can happen when tribal impulses are radically elevated.

Tribalism, for instance, arises when loyalty to the in-group is extremely prioritized, with little tolerance for viewpoints that disrupt the group or weaken its cause, whether true or not. It can be seen in polarized friend-enemy politics and in hostility to outsiders.

Moving on, in Holy Scripture we see many ways that tribal impulses needed to be challenged, curtailed, or contained in order to establish true religion and a healthy society.

Abraham's initial call was a call to break with the deepest tribal instincts: to leave his land, his people, and his father's house, and go to a different land entirely. The other patriarchs were marked by similar traumatic breaks with tribal grounds of identity. While at certain points they probably formed something akin to small sheikhdoms (with very diverse membership), they did not have a land of their own, but were strangers in others’ lands. They did not settle in any single place for long. Their family bonds were relatively weak and children moved away from their parents and formed different groups. They had extensive dealings with people beyond themselves.

Two great early leaders of Israel, Joseph and Moses, learned from Egypt and were caught between worlds. These men were formed in civilizational contexts quite different from their clans and people, and in many respects far advanced beyond them. They were caught between contrasting worlds and needed to be able to stand over against their own people to serve God rather than merely their tribe. Their moments of antagonism with the Israelites highlight this. A narrow in-group solidarity would have compromised their capacity to perform their role.

Later we see much of the justice system among the tribes was given into the hands of one quasi-cosmopolitan tribe, a tribe scattered among the others with no large territory of its own, beyond its various cities. Levi's role protected justice from corruption by tribalism. The Law emphasizes the equity that should be shown in treating both native born and stranger, the impartial judgment that should be delivered upon those closest to you, and generally the threat that excessive in-group loyalty poses to true justice.

A huge emphasis of the book of Deuteronomy is the need for a central sanctuary. Among other things, this opposed tendencies to reduce God to a god of the tribe, a god of a particular location, or to reduce worship to local tribal ritual, designed to underwrite group identity.

In addition to the central sanctuary, the people would later have a king. The king challenged tribalism by establishing a central city and national identity, subordinating regional and tribal identities, locating many core activities of the people's life outside of their tribes. Where the king failed, tribal identities could reassert themselves. For instance, when Saul turned towards tribalism and mercenary loyalties when his authority weakened. Or when the cruelty of Rehoboam turned Israel against Judah.

With the kingdom and a more centralized national identity, the nation became a much more socially differentiated and less homogeneous place, with different classes, regional groups, vocations, and other sets of people whose much more disparate interests needed to be harmonized.

While there were leaders of tribal groups, the nation produced elites of various kinds and decentred the tribes by relating them to a ruling and cultic centre, and to each other within a wider order. It encouraged the emergence of a higher culture, in contrast to folk cultures.

It encouraged the centralization of power with a trained and equipped army, rather than the old militias. It also encouraged trade and cultural exchange and a sort of early cosmopolitan culture at the height of Solomon's reign, for instance. Wisdom flourished in such a context.

If the Levites, the centralized sanctuary, and the monarchy pushed against tribalism, the prophets pushed against the excesses of nationalism. Once again, being part of and loyal to a nation is good, but there are values that must relativize such loyalty and belonging.

The prophets demonstrated God’s concern for nations beyond Israel and Judah. They punctured a nationalist self-righteous complacency. They boldly condemned their nations and hampered their causes. They were most hated by their own people. Sometimes they even sided with enemies!

We see many of these things picked up in the New Testament. Jesus directly challenges excessive family loyalties. He was rejected by his own. He declared that his followers’ enemies might be those of their own household, and that their truest family was those who served God's will. He called disciples to leave their father and mother.

The early Church was chiefly formed by cosmopolitans and its story focuses on cities. Paul was a man of three worlds: a devout Jew, a Roman citizen, and someone well-versed in Greek culture. He could become all things to all men and, in traversing cultures, bring them together in one body.

The Church is a transnational, supranational, and international body. A mobile and missionary Church relativizes boundaries and works through, over, and across them. The Church is a body where a higher and more ultimate union prevents more immediate unions from being idolized.

Having familial and local bonds is very important. ‘Tribes’ can be good too. The Church has tribal dimensions to it, for instance, as we gather in bands to sing and eat together. However, many of the functions of a higher society—justice, scholarship, and true religion—require the limiting or exceeding of tribal impulses and the establishment of elites and cultivation of cosmopolitan values.

Forms of nationalism, cosmopolitanism, or globalism that corrode all local, familial, or regional attachments, or flatten everything out, are destructive of healthy human life. However, a pursuit of justice, truth, and true religion will necessarily push firmly against tribalism.

Relating all this to Christian Nationalism, despite its use of the term 'nationalism', much Christian Nationalism has been more tribalist and sectarian in impulse. It is a dissident movement, rather than a movement striving to form a new centre and consensus among highly diverse groups in the USA.

Consequently, it unsurprisingly lurches between projecting a tribal vision onto the nation as a whole, establishing homogeneous sectarian redoubts, or playing with notions of network states and the like. No real effort is made to wrestle with the reality of deep cultural differences. It tends to function, as many recognize, more as an identity politics for one subset of Americans (perhaps chiefly those Scots-Irish who settled originally in the Appalachian hill country), than as a relativizing of the loyalties and identity of that group within a larger and more diverse polity, which in turn is relativized by the sovereignty of Christ.

The more tribal political vision of Christian Nationalism tends to depend upon unrealistic visions of defeating their opponents, lacking a—dare I say ‘national’—vision of a genuine common good that recognizes that the nation belongs no less to groups that are very different from or opposed to theirs. This requires magnanimity.

The tribalism also makes it resistant to the inherently anti-tribalist dimensions of institutions such as the university or the Church, which will always be serving ends beyond, relativizing the interests of, and manifesting a peoplehood beyond its in-group.

None of this means that the more tribal concerns of Christian Nationalists are altogether without legitimacy, that there aren’t injustices to be addressed, or their loyalties aren't good in principle, but these all need to be kept in their proper places.

Much of this is basic ordo amoris, a matter of rightly ordered loves. It is by no means a bad thing to have a tightly-knit in-group. However, when the loves characteristic of such groups are radicalized, they can be destructive of many of the necessary higher functions of society.

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ On Mere Fidelity, Matt and I were joined by Dr Tim Perry to talk about his latest book, When Politics Becomes Heresy: The Idol of Power and the Gospel of Christ. On the 1,500th anniversary of Boethius’s death, Dr Tom Ward came on the show to discuss his new book, After Stoicism: Last Words of the Last Roman Philosophera.

❧ The Theopolis Podcast’s Deuteronomy series continues, with episodes on Deuteronomy 32: The Song of Moses: Part 3, Deuteronomy 32: The Song of Moses: Part 4, and Deuteronomy 32: Moses’ Death Foretold.

❧ I recently wrote a piece on the problems with pursuing status.

‘Status’ is something that can be correlated with many things worthy of our pursuit: with an honorable reputation, with respectable and responsible standing in our communities, with recognized mastery of our vocations, with access to peers who will stretch and improve us, with participation in important decision-making. However, like speaking of money or power, there are dangers in thinking of and pursuing status as such. Like money and power, status can be approached largely as an instrumental means: as something that is of great usefulness, increasing our potential for action considerably. However, like power and money, status is the sort of thing that can be decidedly ambivalent to ends. People can devote their lives to the pursuit of money and power, while losing sight of higher ends these must serve: the same can easily happen with status. Endeavors in which instrumental means—like money, power, and status—and their pursuit are prioritized are inherently dangerous and can easily become corrupting. We must never stop pressing the question of what ends our status serves.

❧ My series of videos for Theopolis on a Pentecostal politics continues with an episode on ‘The Church and the Mandate of Heaven.’

And concludes with ‘The Church Will Be Political’.

❧ Miles Smith, Assistant Professor of History at Hillsdale College, joined me to discuss the complexities of the Church’s relationship with politics. Miles is the author of the recently published Religion and Republic: Christian America from the Founding to the Civil War. Within our conversation, I also reference his recent Mere Orthodoxy article, ‘Perdition’.

❧ Dr Timothy Edwards is setting up a new liberal arts college in Oxford, Selden College. He joins me to discuss the project and a Christian philosophy of education.

❧ I recorded a version of my reflection ‘Why Mordecai Did Not Bow’, which I first wrote for the Anchored Argosy back in March.

Upcoming Events

❧ Alastair has several smaller events coming up. He will be speaking and preaching at a couple of churches in the Stockport area in just over a month’s time.

❧ The next session of Theopolis’s Civitas group starts on the 14th November.

❧ Alastair will be participating in the next session of Davenant’s ongoing Lilly Grant-funded program working on congregational life in a digital age.

❧ Much of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Alastair and Susannah

I love the critique that Christian Nationalism isn't nationalist enough.

However, I also think it applies to the both of you. How come neither of you have been to the Great Plains? It makes me sad to think that neither of you have seen a proper grassland. Susannah, next time you have a family reunion, you guys ought to consider Fort Robinson State Park in Crawford, Nebraska—one of the country's top sites for family reunions.

If shepherds had more wisdom, perhaps we wouldn't feel the need to pose a dichotomy between the sacred and the political. But, because as a church we still struggle to articulate and teach deep wisdom, we fall prey to these tribal identity traps, and thus feel a need to say "don't sacralize politics and vice versa", as a hedge against our worse tendencies.

It's the old problem of "everyone doing what is right in their own eyes".

I recently ran across a really good example of this dichotomy in action, and how as a church we tend to lose the plot.

Someone was complaining about the recent scandal of some Church of England ministers casually baptizing folks from the Middle East who were claiming asylum, to undergird their asylum claims.

Ostensibly, these ministers were typical liberals, more concerned about social justice than the truth.

But the conservative complainer was lodging his complaint in precisely the wrong area. He was miffed that these casually baptized folks were sullying the national identity, enabled by the Ministers. It made him feel dirty as an Englishman, or something.

What he should have complained about was not the asylum status of the immigrants, but the casual nature of the baptisms.

If they were true converts, then who the hell cares if that resulted in legitimate asylum claims? Let the Englishman feel dirty, if they're real Christians.