№ 35: The Depths of Time

Broadway Boomer patriotism, a wedding in North Carolina, a sailing excursion, Young Writers' Weekend, and a visit upstate.

Young Writers’ Weekend with the Weirdest Anabaptists Ever

Susannah: This past weekend was the culmination of a lot of work (most of it not mine)—we had our first Plough Young Writers’ Weekend, at the Mount Academy in Upstate New York. It’s the boarding high school of the Bruderhof, the community that publishes Plough, and it was—along with everything else—a spectacular location for a writers’ conference. The Bruderhof bought the property from the Redemptorists, a Catholic order: it was built around 1905 as a Redemptorist seminary. Which means that this Anabaptist-run boarding school has an absolutely spectacular Catholic chapel.

They also have a library, a theater, and incredible views of the Hudson River.

The attendees were 25 or so undergraduates and grad students from a variety of colleges and universities - a real mix of people, with one girl coming from California. They group tended towards English majors or former English majors, as is so frequently the case at these things, but there were exceptions: among others, one guy who, following a career in the NFL, was getting a doctorate in theology and ethics from I think Marquette.

We were also joined by a bunch of Bruderhof members of around the same age—many of whom I suspect I will be seeing make their way into the Plough offices in future, because frankly I think the weekend was an incredibly good pitch for journalism as a career and the value of the media in general. The one thing I wish I’d done differently was to organize a showing of His Girl Friday, which is the best become-a-journalist propaganda movie that I know.

The Friday sessions were on the practicalities of media careers: I led sessions on freelancing (with Tara Burton), on book publishing (with Bria Sandford), and Peter Mommsen, Plough’s EIC, and I had a conversation on magazine journalism in general and Plough in particular. These were followed by breakout sessions where students could decide which strand they wanted to learn more about. (Yes, we talked about the future of the kind of work we do in an age of AI also - and we have three pieces on that subject in the just-published Technology issue.)

A Brief Plough History

Plough was founded (as Das neue Werk) in 1920, and we’ve always had an incredibly weird set of writers: we published Karl Leibknecht and Rosa Luxemburg in 1922, the anarchist and founder of the Kibbutz movement, Gustav Landauer, and many more. The magazine always combined both a strong sense of specific principles—predominantly a commitment to Christ’s teachings in the Sermon on the Mount and to the pacifist and communitarian spirit of the Early Church—with a hugely varied set of contributors. Though Eberhard Arnold, the magazine’s founding editor in chief, sharply rejected state communism, as he believed that a state-led, violence-backed compulsion to hold all things in common was a mockery of the free-willed common purse that the Church of Acts 2 and 4 held, he and the community were sympathetic to the anarchistic, socialistic, and communal movements of the time.

Of course, a decade later, these principles and this spirit ran headlong into the SS, which, following the 1933 plebiscite in which the Bruderhof had collectively refused to affirm Hitler’s rule, raided the magazine offices in what would be the first of several raids on the publishing house and community over the next three and a half years (in one of the raids, all of the books in the publishing offices that were bound in red were confiscated, on the belief that books bound in red cloth were probably communist; following another, the community was told that they must no longer educate their children at home, but send them to the state school where they would be indoctrinated in Nazi beliefs).

The final blow came in 1937.

Since Hitler’s rise to power, the community had sent feelers out to Switzerland and in particular to England in the event that they might in fact have to leave; indeed, in advance of one raid, Eberhard had sold the printing press to an English friend of the community for the nominal fee of one pound. This enabled him to inform the extremely irritated SS officer who came to confiscate the press that it was the property of an Englishman, not of a German; since England and Germany were not yet at war, he was forced to leave the press where it was.

That April, in advance of what would almost certainly have been internment of all the adults in Dachau and the farming out of the children to be raised as Nazis, the whole community finally fled—the publishing house staff smuggling out the printed but unbound run of that season’s titles, in packs on their backs, as they walked into Leichtenstein and from there took ship to England. In 1937, Das neue Werk was refounded in England as The Plough.

It’s a story I love to tell—and I love as well to repeat the mission statement that Eberhard Arnold wrote at our founding:

The mission of our publishing house is to proclaim living renewal, to summon people to deeds in the spirit of Jesus, to spread the “mind of Christ” (1 Cor. 2:16) in the social distress of the present day, to apply Christianity publicly, and to testify to God's action in current events. We must get down to the deepest roots of Christianity and demonstrate that they are crucial to solving the urgent problems in contemporary culture. With breadth of vision and energetic daring, our publishing house must steer its course right into the torrent of contemporary thought. Its work in fields that are apparently religiously neutral will lead to new relationships and open new doors. (1920)

I recently found another, earlier mission statement from Eberhard, from when the publishing house and magazine were only ideas:

This task can only be fulfilled in one way: in allowing the gospel to work in creation, producing literary and artistic work in which the witness of the gospel retains the highest place while at the same time representing all that is true, worthy, pure, beautiful and noble (Phil.4:8). This means breaking the cloistered isolation of Christian publishing, in which only explicitly Christian books are promoted exclusively to Christian circles. (1917)

This was the same spirit at work this past weekend, with this new generation of young writers.

Conference: Day 2

The second day of the conference, Saturday, began with a conversation between Santiago Ramos (an editor at Wisdom of Crowds and Bria’s fiancè), Dhananjay Jagannathan (a Columbia philosophy professor and Tara’s husband), Diarmuid Wheeler (the Great Books/history department head at the Mount, though he is Catholic and not a member of the Bruderhof), my fellow Plough editor Alan Koppschall, and me.

The topic was free speech: What does it mean, what is it for, what is its connection to journalism, to the idea of a republic, to the public sphere, to the ideal of government by reasoned debate rather than force, to Christ as the Logos, the Word, whose nature is implanted in each human being. It was the best such conversation I’ve ever been a part of.

This was followed by two more sessions: one with Stephen Adubato about the founding of his new zine, Cracks in Postmodernity, and one with Tara about fiction writing as subcreation, and her experience of writing novels before and after her conversion.

Then we all went over to another Bruderhof property, a sort of camp, and played a bunch of volleyball and foosball and pool and talked about everything in the world and grilled burgers, and tried to figure out where Pete and his family were rowing on the river (they have apparently started a Mommsen Family Crew Club) in order to heckle them from the shoreline, but failed in this attempt.

That night, a select group of us attempted to access the rumored tunnels under the Mount, because if you are in a big old seminary and you have been told that there are secret tunnels under it, and you DON’T attempt to figure out how to get into them, what are you even doing with your life? But unfortunately we were stymied by gates.

Despite these crushing blows, it was among the best Plough events I think we’ve ever done. It’s likely that we’ll continue to do the Young Writers’ Weekends every two years, on the off years from our larger Writers’ Weekends.

Alastair: I returned from our holiday in Ireland refreshed, but with a ballooning inbox and a backlog of work, which I have been very slowly whittling down over the past three weeks. I never seem to get on top of the correspondence!

Punctuating the work, we have made the most of some glorious summer’s weather in New York, walking in our neighbourhood and beyond. Even though it is only a few blocks away, I had only walked in Riverside Park once before; we have typically walked in the city, or in Central Park. Over the last few weeks, we have visited it on a few occasions. We have also tried our local Van Leeuwen Ice Cream shop for the first time.

The social pace of our lives has generally been a little slower since our last post, but we have spent some very pleasant time with friends. Some friends recently returned from an Italian trip and we all discussed the things we loved or missed about Italy in a delightful Italian restaurant near our church. We had a wonderful Ethiopian meal with some friends who are about to leave the area (leaving the PATH in Jersey City, Susannah turned to me excitedly and said, “we’re on the continent!”). We also had a games evening with a friend group.

Just over a week ago, the weather was so glorious that, on a whim, we decided to take a circuitous walk home from church, through Greenwich Village, down to Hudson River Park, along the High Line, then past the Intrepid and through Riverside Park, before returning home.

I am not a city person by nature, but I often feel extraordinarily blessed to live where we do. We are in the very centre of New York, and besides all the culture and energy of the city, we are surrounded by natural beauty.

For my birthday last week, Susannah planned a very special outing. She used to be a deckhand on the schooner Clipper City, which I had not yet seen. She got us tickets for a sightseeing trip to the Statue of Liberty and back.

Clipper City is berthed in Pier 17, near the Brooklyn Bridge. We arrived early, so wandered around and enjoyed the view of the Bridge before boarding the vessel. Susannah could barely contain her excitement at the prospect of being on Clipper City again, which was fun to watch!

It was a spectacular day for sailing, sunlight scintillating on the water. We went from the entrance of the East River—which, despite its name, is a tidal strait, rather than a river—past Governors Island, Ellis Island, and towards the Statue of Liberty, before returning.

Besides seeing it from the air, I had never properly seen the Statue of Liberty since I first came to New York, over two years ago. Now I can finally say that I have seen what is arguably New York’s most iconic sight!

The next day we flew down to Charlotte, en route to Boone, where we were attending the wedding of a dear friend of mine, someone I met during my time in Durham. We had a long drive from the airport with a couple of guys with whom we had some fascinating conversation, heading straight to the wedding rehearsal on our arrival. After the wedding rehearsal the party gathered for a meal, and we had the opportunity to get to know some more of the bride’s family and friends and the groom’s father. We had only met the bride once before, when they visited us in New York last August.

I was one of the groomsmen. The groom, another of the groomsmen, and I started the day at a cabin, where we had breakfast and got ready for the ceremony. The weather was perfect and the beauty of Appalachia was everywhere on display as we drove to the church, a picturesque white wooden building on a hillside. Before the ceremony, we had some photos taken with the other groomsmen.

A wedding is always a joyous affair, but this one felt especially so. After further photos of the wedding party outside of the church, we joined the rest of the company for the reception at the back of the church. We ate, had speeches, danced (well, Susannah danced), and talked for hours. Later Susannah, one of the groomsmen, and I joined the bride and groom at a nearby bar, where we ate and chatted. We then all gathered with others for further festivities, which continued into the night.

Over the course of the weekend, we had over a dozen lengthy conversations with fascinating people, with several of whom we will doubtless be in longer term contact. We discovered some remarkable points of connection and common friends with some of them. Although we travel a lot, meet hundreds of people every year, and have extensive networks, we often sense God’s hand in some of the serendipitous and surprising ways that our paths cross with others. It was also wonderful to get to know many of the friends and family of the bride, and be even more struck by how perfect a match she is for my friend.

The next day we attended an Anglican church, where we met some further people with whom we will probably be in contact in the future. Our flight from Charlotte that evening was cancelled, and we had been put on a flight the next morning instead. In the early afternoon we drove to Charlotte. Due to the change in our schedule, we had free time in Charlotte to fill. Our experience has been that the element of unpredictability in our schedules has allowed for some wonderful serendipity to occur and Sunday afternoon was no exception. A friend suggested that we meet up with an online acquaintance and her family in Charlotte and our plans aligned. We had a truly delightful time with them, before heading to an airport hotel for the evening.

[I am writing the following about a week after the above.] Over the last few days, I taught the final of my classes and held my last office hour for my Davenant Hall course. The course was an enjoyable one to teach, but I will be glad to have a reduced workload. I do not teach again for for the next few months, which will hopefully give me more time for writing projects, which have languished of late.

After church, navigating the Pride Day crowds, and a meal with some friends on Sunday, I took the train upstate to Hudson, to spend a relaxing few days upstate in Ghent, with Susannah’s father and stepmother. The train route up the Hudson River is one of my favourites, with so many stunning views.

The area is beautiful, young deer were frolicking in the garden outside our window, and the weather was glorious for the duration of our visit. We passed a few delightful days working, enjoying meals out, walking, catching up, and watching things together. Somehow, Susannah had never watched The Godfather; we watched it on Sunday and now she has strong opinions! Last night we also watched an episode of Law and Order and a scene from The Education of Max Bickford, both written by my father-in-law; they were brilliant and it was fascinating to watch them and discuss them afterwards.

We travelled back down early this afternoon and are now back in New York, with another busy week ahead of us.

American Patriotism, Old Broadway Style

Susannah: I’ve been hypothetically joining the Lamb’s Club since … maybe the beginning of Covid. But now I’m actually joining; I’ve got my interview on the 11th and my two letters of recommendation are in. All it took was my friend Tara nagging me for four years, and then Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Shepherd (i.e. head of the club; he is also the official custodian of Dorothy Parker’s mink coat, which he keeps in cold storage on Long Island and brings out on ceremonial occasions) nagging my father (when my dad was there for an event in honor of Debby Applegate’s biography of my great-great-aunt, Polly Adler.)

My joining was in certain ways a fraught subject. The Lambs is one of NYC’s two theatrical clubs; the other one is the Players, which is on Gramercy Park. My dad has been a member of the Players for years; I grew up going there, and used to bring friends to drinks there, and we would charge them to my dad’s membership. Once, a decade ago, I was there by myself and I overheard two guys talking about a movie they were making based on the story of Noah. I struck up a conversation with them about it. “Evangelicals will hate it,” one of them said, grinning. That was Aronofsky. The other guy was his co-writer, Ari Handel.

In my experience Evangelicals don’t particularly hate it, especially the ones who are into the Book of Enoch and Michael Heiser and so on, and who listen to the Lord of Spirits podcasts. You can build a lot of cred with people by including cool nephilim in your screenplay, is I think the takeaway here. Alastair claims that the Book of Enoch should be regarded as Bible fan fiction and is annoyed by my speculation that the Watchers are a seriously big deal and that probably the Greek gods are best understood as nephilim, and that Hercules is best understood as one of the half-human offspring of nephilim and human women. But I think his annoyance is unreasonable [Alastair: I’m not entirely averse to such speculation. See here, for instance.].

Anyway so we have this family connection to the Players, and when I was asked to join the Lambs, I had to get dad’s OK. He was very fine with this idea, so really the only holdup has been my own inefficiency, which has now been rectified, and as I say, I’m joining.

The Lambs is in midtown. Having lost its building, it has relocated its furnishings and memorabilia to a single floor in the Women’s Republican Club building. This leads, as you might imagine, to all kinds of madcap hijinks, as the Women’s Republican women and the membership of the Lambs share bar space.

Most of the members of the Lambs are over 75; most are former Broadway hoofers and singers, who gather together and once a month have a performance where they get up in front of an audience to do their old numbers, and occasionally a new one. However at this point a substantial minority are millennials—and even some Zoomers—who have made their way there by the strange social osmosis of New York City. A lot of them are also theater people, but more in the sense of being theater kids rather than working Broadway actors. That’s our crowd.

So anyway, that was the mix of people in play when, several weeks ago, we all showed up to the annual Lambs Celebration of America evening. The theater kids were there, and the Women’s Republican women, and some younger guys who looked like they were also there under the protective maternal aegis of Women’s Republicanism. But the evening belonged to the old Broadway folk.

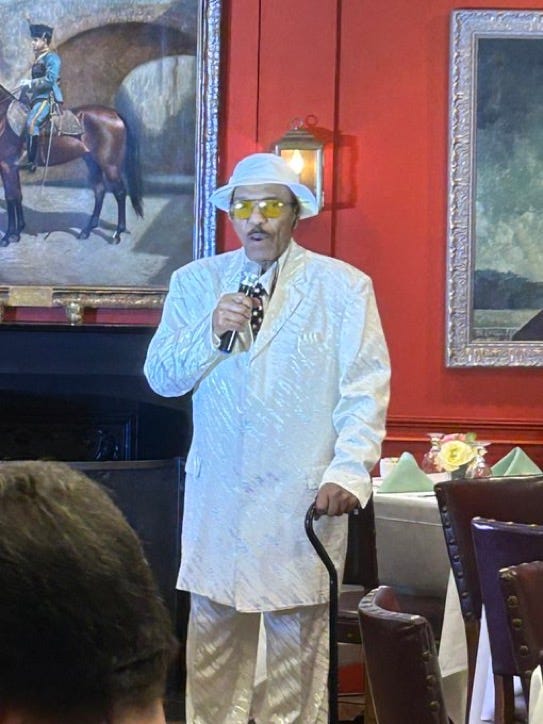

The guy who was the organizer had been doing this annual Celebration of America for about as long as he’s been a member—that was my impression, at least. And he’s been a member for sixty years. At 95, he is I believe the second oldest Lamb. His name is Steve DePass, and he was discovered as a child by Bing Crosby. He was emceeing; he sang a couple of his own songs, and other Lambs sang America the Beautiful and Stars and Stripes Forever and also a ton of obscure songs cut from musicals of the forties and fifties, all in some way relating to patriotism, and then we all sang the Star Spangled Banner together.

They all wore red, white and blue, and there was in the entire gathering not a hint of irony or self-consciousness. It was the most inspiring and moving political event I’ve been to in a while. All these elders, senior Boomers and Silent Generation people, formed and were formed by the country. Their America is the American centrist liberal consensus of the second half of the Twentieth Century. This is the patriotism of Irving Berlin and the Gershwins, of Herman Wouk and Leon Uris, of the Emma Lazarus poem at the base of the Statue of Liberty. Tom Hanks, though he is a generation younger, is an avatar of that spirit.

The Lambs had no sense that patriotism is the exclusive purview of Red State people or that they as New Yorkers, Broadway folk, were somehow required to not express their fervent love of the country. America was for them, and they were for America.

I ended the evening proud of my country, of my city, and of my club. I write this the day you will receive it, fifteen minutes before heading out for the friend group Fourth of July picnic, and I am grateful to those elders for reminding me of the ideal of a government of equal justice under law, and of an America which welcomes all kinds of weirdos, including musical theater people.

Finding Time

There are countless scholars who have helped me in my reading of various passages of Scripture. I have gleaned insights and keys from them that have unlocked texts that once perplexed me. However, no scholar has done so much to teach me how to read the Scripture more generally than James Jordan. From Jordan I have learned skills that I bring to every text that I read and an integrative theological vision which helps to hold them together.

Jordan’s reading of Scripture, and his thought more generally, has significant breadth to it and develops out of an array of influences. One finds a constellation of insights in Jordan, all of which can assist one in reading the Scripture. However, he has always had an attraction to bigger ideas that might serve to integrate one’s wider field of intellectual enquiry. For Jordan, figures like Cornelius Van Til (presuppositionalism), Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy (the cross of reality), David Dorsey (chiastic structure), René Girard (the scapegoat mechanism), among several others have all offered radical insights that inform his approach as a whole. While Jordan’s thinking doubtless also draws upon the work of more narrowly-focused writers and their specific insights, big ideas have always been particularly important for it.

The effectiveness of Jordan in forming his readers’ entire posture of interpretation probably arises in large measure from his peculiar gifts of recognizing patterns, developing interpretative heuristics (his priest, king, prophetic framework, for instance), and his synthesis and integration of a variety of big insights from others into an approach that offers powerful purchase upon the scriptures. There are many elements that constitute Jordan’s approach. If you have not already done so, I would recommend that you read his most seminal work, Through New Eyes: Developing a Biblical View of the World, to learn some of its fundamentals.

Within the array of his insights and emphases, I think it is possible to identify some deeper common themes. The one that, to my mind, might be most deserving of attention is the part that time plays within Jordan’s theological vision and biblical hermeneutics. Along with a few other theologians and biblical scholars, Jordan gave me an appreciation of time and of temporal categories within theology.

Beyond Jordan, temporal categories were downplayed in much of the thinking to which I was exposed in my theological formation. Much modern theology, even biblical theology, is implicitly spatialized, approached as if it involved the consideration of the logical relationships between doctrines in a timeless space. Even when time is present, we may be dulled to it. For example, concepts such as ‘old covenant’ and ‘new covenant’, while referring to two ages, the second succeeding the first, can often be treated as if they were disconnected stable states of affairs to be juxtaposed as contrasting administrations. Within such approaches, there is a weak sense of the maturation of the one into the other, or of the unfolding phases within each.

With the privileging of sight and space in modernity, temporal realities in theology have often been transposed into spatial categories or downplayed. For me, Jordan’s work was the initial and primary impetus for me to give temporal categories a greater prominence in my theology. After Jordan, other theologians helped me to develop my thinking in this area—Jeremy Begbie, Catherine Pickstock, N.T. Wright, Geoffrey Wainwright, David Bentley Hart, Douglas Knight, Peter Candler, Moshe Halbertal, among many others—but it was Jordan’s work to which I most often returned and to which I have always been most indebted. In him time was everywhere and, as I became attuned to it, its importance became increasingly apparent.

As moderns, our sense of time is typically formed by the clock, which divides time into discrete successive moments of uniform duration, with specific times identifiable according to a common system of measurement. Things such as timelines and our common quantitative durations of time can subtly spatialize time; the timeline, for instance, represents a period of time as uniform and present on a single axis. As our daily liturgies of labour are ordered by the clock, it is profoundly formative of our perception of time more generally. The measurement of time made possible by the clock certainly has its benefits. Sharing a set time with others and being able to measure its duration enables us to organize and synchronize activity to a degree that would be impossible otherwise. Yet the dominance of clock-time in our daily routines can leave us with a very stunted sense of time more generally. Indeed, time as it functions in theology is in almost all respects quite different from clock-time.

One of the greatest advocates of reconceptualizing time for the sake of theology has been Jeremy Begbie (Theology, Music and Time is a good place to start), who argues that music provides us with a peculiarly apt conceptual metaphor for thinking about it. I have discussed Begbie’s work at greater length here. Music also equips us to think about the unity and mutual interpenetration of times, as Henri Bergson appreciated:

Could we not say that, if these notes succeed one another, we still perceive them as if they were inside one another and their ensemble were like a living being whose parts, though distinct, interpenetrate through the very effect of their solidarity? The proof is that we break the rhythm by holding one note of the melody too long. It is not its exaggerated length as such that will avert us to our mistake, but rather the qualitative change brought to the musical phrase as a whole. One could thus conceive succession without distinction as a musical penetration, a solidarity, an intimate organization of elements of which each would be representative of the whole, indistinguishable from it, and would not isolate itself from the whole except for abstract thought. [Suzanne Guerlac, Thinking in Time: An Introduction to Henri Bergson, 62]

Such a ‘musical’ understanding of time will equip us to understand the way an institution like the Sabbath challenges the ‘homogeneous, empty time’ of modernity, functioning as a ‘higher time’ that can ‘gather, assemble, reorder, and punctuate’ our time more generally (Charles Taylor, A Secular Age, 54). The Sabbath established a weekly rhythm and temporal unit, it memorializes foundational acts of creation and redemption (the Exodus and, for Christians, the resurrection), it gathers up the events of the past week in confession, absolution, offering, and communion, initiates the new week in reorientation and commission, and orients us towards the awaited final Sabbath.

Jordan’s emphasis upon liturgy and ritual as a ‘microchron’ of history—a symbolic performance of larger historical patterns in miniature—is important here. The ‘higher time’ of liturgy equips us for, punctuates and orders, and orients us within our more quotidian existence. Likewise, liturgy is a ‘musical’ coordination of a congregation, in body, voice, and mind, that forms and integrates the human person and community and has its own unity and movement (Jordan emphasizes the unity of the temporal movement of liturgy, against its fracturing into discrete and separate elements).

The sacraments also situate us in the tension between the realized and inaugurated and awaited fulfilment. In baptism we are buried with Christ, baptized into his death, in anticipation of participation in his resurrection. In the Eucharist we memorialize his death until he comes; the past deliverance is recalled and the Wedding Supper of the Lamb is anticipated. Douglas Farrow provocatively suggests that John Calvin’s theology of the Supper, whereby things distant can be brought near by the work of the Spirit, would be strengthened by thinking of this temporally: the Eucharist must be understood in the light of eschatology (see also the work of Geoffrey Wainwright in this regard).

Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy is a core influence upon Jordan’s understanding of time. Central to much of Rosenstock-Huessy’s thought was the ‘cross of reality’, a concept which sought to capture the wrestling with forces operating on different axes that constitute our existence. Roughly characterized, the cross of reality positions human experience at the centre of forces moving backward, forward, inward, and outward. The first two of these—backward and forward—concern the past and the future respectively, while the second two—inward and outward—are chiefly (though not entirely) spatial.

In contrast to modern assumptions, within which we might fancy ourselves to live within a continuous and uniform timeline, Rosenstock-Huessy observed that the ‘time’ that we inhabit is one that must be constituted through a relationship with past and future. Our ‘time’ is formed by things such as education (where the gap between ‘distemporaries’ is traversed in the transmission of culture), marriage (within which we make vows that bind us for life, establishing a consistency across our lifespan), child-bearing (in whom we have a living investment in a time after our deaths), the receipt of a legacy (which commits us to honour and ensure the fruitfulness of the sacrifices of those that preceded us), etc.

Our ‘backward’ relationship with the past can be seen in the repeated patterns of our lives, in our loyalty to those who have preceded us (chiefly our father and mother), and in the enduring realities of an age. Rosenstock-Huessy terms this ‘epochal time’. Our ‘forward’ relationship with time, by contrast, is ‘dramatic time’, breaking with the past and its patterns and creating something new. From the perspective of the individual’s life, a wedding represents such ‘dramatic time’: the man leaves his father and mother and is joined to his wife, creating the new common time of their marriage.

Rosenstock-Huessy’s ‘inward’ and ‘outward’ relationships, while typically more spatial in character, can also be related to time. When we are ‘lost in a moment’, we have an inward relationship to time (inward time is ‘lyrical time’), while an outward relationship to time (‘analytical time’) is very familiar to us in our various forms of time management.

Our relationship with the past and the future can break down. A revolution does not merely start something new, but jettisons the past in order to do so. Decadence stagnates, failing to reach towards the future. The way time is formed by human action and relation within Rosenstock-Huessy’s work makes us more alert to the importance of things such as (inter)generational dynamics, traditions, and transitions. Times are established, passed on, ended or remade. There are deaths and resurrections. One generation passes on its baton to the next, or fumbles the process. The sacrifices of one generation are rewarded in the fruit produced by the next, or betrayed by their dishonour or fruitlessness.

Similar processes define the lives of societies, communities, families, and individuals. Themes of maturation, for instance, lie near the heart of Jordan’s theology. All human life moves through stages of growth and must negotiate challenging transitions and crises. There are times of sowing and of reaping. Mid-life, for example, is a time of crisis for many as we experience radical transformations in the sense of our time. Once expansive possibilities no longer exist and we are left with stubborn and seemingly inescapable actualities: there may be no more second chances. We taste the harvest of earlier times of sowing in our lives and can be forced to wrestle with uncomfortable questions about our characters. Final horizons feel much nearer, forcing us to face questions of mortality, often for the first time. The challenge of successfully passing the baton to the next generation occupies more of our attention and questions of what we will leave behind might begin to haunt us. Our faith must grow and mature to meet several such crises: the faith of the sixteen-year-old will not be adequate for the challenges faced by those who most parent one.

Jordan discusses maturation using a pattern such as that of ‘priest-king-prophet’. The priest works in terms of the external black-and-white and perennial principles of the law (‘do this, don’t do that’). The king must internalize the law in understanding and operate in terms of wisdom. He is characterized by prudence and discretion, working in terms of a wisdom that appreciates the difference between times and discerning the actions that are appropriate in each (Ecclesiastes 3:1-8). Prophets take things a step further: as they have taken the word into them, they can speak with a creative power, building up and casting down, fashioning new worlds (e.g. Jeremiah 1:9-10).

This might be compared to the way that someone learns to play a musical instrument, moving from playing scales and simple pieces (law), to developing a more expressive style, learning skills of ornamentation and elaborating upon existing pieces (wisdom), to the creation of entirely new compositions in a distinctive style of one’s own (prophecy). Jordan’s priest-king-prophet paradigm—which is much more elaborate than this brief summary can do justice to—is helpful in a variety of contexts, not least in expressing the transforming relationship between the people of God and the Scripture: from the external word of the law, to the internalized word of song and wisdom, to the empowering and authorizing word of prophecy.

Rosenstock-Huessy’s insight into the character of time is deeply generative for theology. Unsettling and expanding our narrow modern conceptions of time, it offers us categories that are much fuller and more fitting.

Jordan’s thinking about time draws from an attentive reading of the opening chapters of Genesis. The establishment of the alternation of day and night on the first day with the creation of light, the ordering of time with the lights of the fourth day, and the completion of the sequence of the week with the rest of the seventh day are all important in Jordan’s understanding. Both in Genesis 1 and 2, Jordan alerts his readers to the implied incompleteness of the creation, that it is good but not perfect: the ground must be tilled, humanity must fill the earth, the gold of Havilah must be brought into the garden. Creation must mature, exceeding its origin.

Sabbath makes it more possible for us to step back from our labours, to memorialize the great deeds of the Lord in the past, to look towards the future. Considered in the light of Rosenstock-Huessy’s framework, it makes it possible for us to have a much more extensive sense of the time that we inhabit; it protects us from decadence, revolution, and unmindful submersion in the immediacy of the present. Each Sabbath we can sum up and complete the preceding six days and initiate the week that follows.

An emphasis upon time can also encourage a deeper sense of the transience and utter dependence of creation, something generally much less apparent where spatial categories dominate. As I have written elsewhere:

This brings into focus elements of creation that are less clear when we think of creation as if it were the construction of solid objects that endure through the homogeneous medium of time, or are subjected to its cruel ravages. Time is not just something that happens to us, but is integral to what we are. Thinking in such a manner teaches us to remember and appreciate our own finitude and to value and reflect more closely upon the changing seasons of our lives. Silence, the face over which the spirit of music hovers, reminds us of our enduring relationship to nothingness, as those who have been brought forth from it by God’s creative voice.

For Jordan, history is musical, that is, typological. History manifests the workings of a ‘higher time’ within it—a higher time represented in the ‘microchrons’ of ritual. The way that ritual microchrons relate to the larger movement of history can be seen in places such as the book of Revelation, which presents climactic events of history in terms of a heavenly liturgy. History has repeated patterns (the Exodus pattern being one such example), unity, and interpenetrating realities. Because history is typological and musical, it is prophetic: past events of redemption anticipate later events and later events recapitulate earlier ones.

Prophecy can have a ‘telescopic’ character, as prophecies can be expanded to relate to several escalating fulfilments on successive horizons. Prophecies of the new covenant, for instance, can relate to initial fulfilments in the period following the return from exile, to the dawn of the new covenant in the work of Christ, to the period following the overlap of the old covenant order and the inaugurated new covenant, and to the final consummation of all things. This offers a richer understanding of the character of redemption commonly described as ‘already/not yet’. There is a linear and teleological character to history, but also a cyclical and repeating character: directionality is not contrary to repetition.

Likewise, for Jordan history has a deep unity, a conviction that shapes the way that he reads the Scriptures. His profound instinct for intertextuality is related to his sense of the character of time and history. The narratives of Scripture manifest a higher time and play out an escalating musical movement, bound together by repeated patterns in which we can perceive the interpenetration of times, and processes of remembrance and prophetic anticipation that integrate them. The sort of historiography that arises from such a sense—and reality—of history is quite different from that which arises from the flattened time-consciousness of modernity. With the loss of a sense of the reality of a ‘higher time’ and the typological character of history that follows from it, realities such as ‘distance’ in time assume a radically different character. Considered in terms of a higher—or deeper—reality to time, it should be clear that the intervention of two thousand years could never separate our time from the presence of the once-for-all events of the cross and resurrection of Christ!

Besides this, ‘redemptive history’—which Jordan would remind us is about much more than deliverance from sin and death, including maturation and a sort of ‘holy war’ against fallen angels—has a prominence in his theology and soteriology that it typically lacks in Reformed theologies. In some such accounts, one might even be left with the impression that redemptive history is a sort of ‘making of’ account for a timeless salvation system for detached individuals. In contrast to this, for Jordan, the primary locus of salvation is the public realm of history—in the incarnation, death, resurrection, ascension, and return of Christ—rather than the privacy of the individual heart. We are saved as we are caught up in a much greater ‘story’, united to Christ in his body the Church, experiencing the firstfruits of his fulfilment of the promises to Israel and realization of the hopes of the nations, and awaiting the future consummation of all creation in him.

Considered from another angle, something changed for the whole people of God at a climactic juncture in history, Hades was harrowed and the saints were raised to rule with Christ in the first resurrection. Our sense of this is strengthened in the practice of the Church year, which in its feasts foregrounds the once-for-all historical deliverance that Christ accomplished in the fulness of the times as the ground of our salvation and common life. Our soteriological vocabulary, terms such as ‘justification’, ‘adoption’, ‘sanctification’, ‘glorification’, etc. must be rooted in these historical events or they will lose their true sense. In such a vision of history, eschatology naturally has much greater prominence and traction in Jordan’s wider theology, factoring into his soteriology to a degree that it seldom does for others.

As moderns most accustomed to silent private reading of texts from a page, we can become somewhat dulled to the temporal character of texts, to the way a text—like the events it recounts—unfolds over time. A text that is performed and heard has a more immediately apparent temporal character; it is not always already present on the space of the page, but ‘arrives’ over the course of its performance. Considered as something arriving over time, rather than something always already present, its meaning is not entirely settled and can shift, surprise, or wrongfoot the hearer.

Consideration of this can train us to be attentive to texts in different ways, more alert to the process of the story’s unfolding and to states of affairs at critical junctures. Perhaps the greatest exemplar of such attention to biblical narrative of whom I know is Rabbi David Fohrman, a reader of Scripture who is peculiarly skilled at following the temporal movement of a story. He is very good at preventing the final resolution of a story to determine his reading of earlier junctures to a degree that dulls surprise or a sense of the contingency of events. He invites us to pause at key moments and consider what various parties knew, what they might have anticipated, and how they stood relative to each other. At other points he challenges us to consider what we the reader would expect to happen next, if we did not already know how the story ended. He encourages us to reflect upon counterfactual courses that events could have taken, which the reader who spatializes texts is much less likely to consider. Yet the meaning of what actually happened can be profoundly shaped by recognition of such ‘roads not taken’, much as the expectations a composer or performer has encouraged in those listening to their work must colour our understanding of the significance of a musical piece taking a direction that confounds them. Such attention can be remarkably productive of insight, yet is widely neglected by those who lack such a sense of the character of time and its importance for our reading.

A further aspect of Jordan’s attention to time is encountered in more speculative works of his such as Crisis, Opportunity, and the Christian Future. A largely spatialized understanding of the Christian faith can present the entire span of post-scriptural history as a sort of essentially formless profane time detached from the sort of ‘higher time’ we encounter in the events of Scripture. Jordan parts ways with such an approach, bringing the history we inhabit into direct connection with a higher time in a variety of manners. For Jordan, history is not demoted to a largely meaningless meandering of successive events after the Ascension, but is a providential maturation of humanity and spread of the Church.

This is grounded in a postmillennial vision of the kingdom of God, its growth and spread. Humanity’s maturation is not merely an uninterrupted progression, but involves the death and resurrection of worlds. Writing in 1994, Jordan suggested that much history can be understood as a movement from an age of tribes, to an age of nations, to a cosmopolitan age, arguing that the West was moving towards the death of a cosmopolitan age, which would fracture into a form of neo-tribalism. There are many points at which readers might take issue with Jordan’s analysis, but his fundamental sense of the ordered character of post-scriptural history is a powerful one.

Jordan’s account of time can be grounded in Christ. Christ, coming in the fulness of time, is the one who was before time began, and the one in whom our whom our future is disclosed. He is the unifying theme of the entirety of history, which will be gathered up in him. He is the light of the first day and the dawn of the Day of the Lord, the Alpha and Omega, beginning and end.

Like many things in Jordan, his account of time is not found in any single place and several aspects of it are never directly explored, yet it pervades and informs the whole. Much of it remains implicit and underdeveloped, while manifesting something of the deeper integrity of the broader vision he presents. There are aspects of it, such as his sense of eternity and the ‘time’ of God, that remain less clear to me (I cannot recall any detailed treatment that he gives them). Primarily, however, Jordan’s work is a beginning and invitation to a fuller recovery of temporal reality in Christian thought, an invitation I hope many will take up.

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ The Theopolis Podcast’s Deuteronomy series continues, with an episode on Deuteronomy 27: The Altar on Mount Ebal.

❧ I wrote a piece for Logos’ Word by Word blog’s recent series on typology, ‘The Christological Character of Typological Reading’:

The incarnation grounds the literal sense, securing the sense of Holy Scripture in history and its events. The transfiguration manifests the allegorical sense, the glory of Christ that is veiled in the letter of Scripture. The cross and resurrection display the moral or tropological sense of Scripture, the shape of the righteous life exemplified in Christ. The Parousia is the disclosure and descent of the heavenly referents to earth, the anagogical sense embodied in the Savior for whose return and unveiling we pray.

Finally, the event of Pentecost, the gift of the Spirit of Christ, enables the church to perceive, participate in, and proclaim the Word in its fuller reality. By the Spirit we can find the veiled glory of Christ in the letter of Holy Scripture, discover the form of Christ in his sufferings and glories, and anticipate the higher heavenly realities concerning which they bear witness. As the apostle Paul expresses, the Spirit discloses the glories of Scripture, transforms its readers, and empowers them for witness…

❧ I expanded my recent ‘The Internet is the Negative World’ piece for Samuel James, who published it over on his site, Digital Liturgies.

In our offline existence, differences between contexts, realms (e.g. public or private), and circles of conversation tend to be much more clearly defined and apparent and our differing realms of speech are typically highly bounded, their limits known, and the people within them evident. This makes it possible to vary our forms of speech and behaviour in various settings. With everyone becoming much more visible to everyone else, the power of social pressure and surveillance grew more and more pronounced. With such visibility, what had formerly been more like a realm of subterranean tunnels was now in many parts like a vast plain with limited shelter or cover, filled with masses of people who were moving as herds, anxious about breaking with the social consensus of their groups and suffering the consequences. Much of the anxiety characteristic of ‘negative world’ arises from this bizarre and novel discursive environment, within we are both the subjects and enforcers of a great social Panopticon and our discursive spaces can be much more threatening for those articulating perspectives that diverge from the norm.

❧ The recordings from my recent Beyond Rules and Roles: Scripture and the Sexes series has now been published on Davenant’s YouTube channel.

❧ My latest piece on the Theopolis blog, a response to Gerald Hiestand, has been published.

Christians must have an active concern for the flourishing of women in contemporary society, a society radically different from former ones. There is no timeless blueprint to be enacted, former idyll that might be repristinated, enduring utopia to be achieved, nor uncomplicated process of emancipation to be continued. Rather, we must prudently, attentively, and critically respond and adapt to the novel and rapidly changing conditions of modern society. This is a task for which both wisdom and a vision for a society in which men and women thrive together formed by Scripture will greatly help and orient us.

Susannah: I’m just going to send you all to the Plough Technology issue, which is in my opinion one of the best we’ve ever done. Of particular note:

David Schaengold’s “Computers Can’t Do Math,” on what artificial intelligence is and isn’t and why computers can not only not write poems, they also cannot do math

Arlie Coles’ slow-build jeremiad “ChatGPT Goes to Church,” on one particular way in which we must refuse to use these technologies

JL Wall’s “From Scrolls to Scrolling in Synagogue,” on how technologies of reading have shaped Jewish liturgical life

Brian Miller’s “Give Me A Place,” on his deep love of rock bars, six foot long iron bars that you use to smash up rocks when you are attempting to dig a post hole and run into a rock

and Simon Oliver’s “Towards a Gift Economy.”

Upcoming Events

❧ Alastair will be speaking at the forthcoming Theopolis Ministry Conference on July 15th and 16th. Find out more about it here!

❧ Most of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Alastair and Susannah

That is definitely an ear tingling mission statement by Arnold. Positively theonomic in its insistence upon the lordship of Christ and the absence of neutrality.

And the origin story is thrilling indeed.

Arnold's insistence upon God's action in current events is right at home alongside James Jordan's insistence on the Divine superintendence of history.

I've gotten an immeasurable amount of good out of Jordan's discourses on the progressive maturity of mankind under God.

It would be interesting and fun to overlay Jordan's prophet priest king motifs with Frame and Poythess's triperspectivalism.

That's a fine schoonah there. Looks ship shape and Bristol fashion. Baggy wrinkle is not tired at all. Believe me, there is nothing–absolutely nothing–half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats.

So, since you name-dropped Lord of the Spirits, I took a listen to their latest episode. How would you rate them as far as trustworthiness? I can filter what are Orthodox peculiarities that I wouldn’t subscribe to, but overall are they pretty sound?