№ 16: Spirits in Prison

The Convivium, Peter's spirits in prison, self-mastery as the beginning of true politics

Dear all,

Alastair is still in Davenant House and Susannah is preparing for our forthcoming house move. It is all happening right now!

Susannah: Yes, it’s true. We’re moving from Queens to Susannah’s home Island of Manhattan, which involves, inter alia, an estimated 80 boxes of books. Prayers appreciated. We’ll be on the Upper West Side, a block and a half from Central Park, and yes we will have room for guests, uh, once everything settles down. DM for more details.

Also it is very weird that we now have a thousand subscribers to this - who ARE you all? What is even going ON?

Prayers appreciated too for the completely insane amount of general Stuff going on over the next couple of months. We have four weddings coming up, three of which we’re traveling for - this is VERY GOOD, and if you are getting married and are our friends, we definitely want to be invited, but at the same time we are running around like crazy people, so if we seem demented, that’s why.

Unrelated: We’ve started watching the Stephen Fry/Hugh Laurie Jeeves & Wooster, which Alastair has seen only a couple of episodes of previously, while Susannah has watched about 1/3. It is sublime.

Spirits in Prison

Alastair: On Sunday morning, I preached on 1 Peter 3:18-22, a short text with several elements that cause no small debate among scholars, not least Peter’s reference to Christ preaching to the spirits in prison and his statement that baptism saves us. Susannah was disappointed not to hear my sermon, as she was eager to know my thoughts on the ‘spirits in prison’. The following is partly in answer to her interest, but mostly concerns the proper reading of this detail within the passage more generally.

Peter begins by drawing what seems to be a comparison between our suffering and Christ’s suffering. He then elaborates on the nature and purpose of Christ’s suffering, before referencing Christ’s preaching to spirits in prison, speaking of the rebellion prior to the Flood, from which he moves to describing the redemption of Noah and his family through the Ark, which Peter then relates to baptism, the nature and power of which he then discusses, before concluding the chapter with a description of the ascension and Christ’s enthronement over all. All this within only five verses!

One more general challenge we face in hearing these verses—and any such passage—is discerning a consistent and coherent movement of thought in what might appear to some to be a highly digressive and disjointed passage. This challenge is, unsurprisingly, often forgotten or neglected. It is easy to abstract verses from their contexts and handle them piecemeal, especially for systematic theologians and those for whom the text is mostly raw material for the doctrinal, moral, or other interests that they bring to it. Many readers of 1 Peter 3:21, for instance, might merely be interested in defending or proof-texting their doctrine of baptism; many contemporary readers of verses 19-20 are only interested in them to the extent that they have bearing on readings of Genesis 6 and the question of biblical use of the book of Enoch. For such readers, consideration of Peter’s broader line of thought likely represents a distraction or is relatively uninteresting to them. We must, however, listen through the text before we abstract elements from it.

When hearing a passage like 1 Peter 3, we must listen for a strong and plausible through-line of reasoning that unites it. While we should be open to the possible existence of tangents in such texts, other things being equal, readings that maintain a consistent thread of thought moving through a passage will be much more persuasive than those which cannot.

That Peter picks up further elements of verses 18-22 and themes from the verses preceding it in chapter 4 strengthens the case that Peter’s argument is of one piece. 1 Peter 3:18 to 4:1 also seems to have some degree of internal structure:

A “For Christ also suffered once for sins, the righteous for the unrighteous, that he might bring us to God, being put to death in the flesh but made alive in the spirit…” (18)

B “…in which he went and proclaimed to the spirits in prison…” (19)

C “…in the days of Noah, while the ark was being prepared, in which a few … were brought safely through water.” (20)

C’ “Baptism, which corresponds to this, now saves you…” (21)

B’ “…who has gone into heaven and is at the right hand of God, with angels, authorities, and powers having been subjected to him.” (22)

A’ “Since therefore Christ suffered in the flesh…” (4:1)

In the passages preceding this, Peter has spoken a lot about Christian suffering and the way that Christ’s suffering provides a model for believers. He charged Christians to live quiet and submissive lives in their societies, honouring rulers and not responding to mistreatment in kind. “Do not repay evil for evil or reviling for reviling, but on the contrary, bless, for to this you were called, that you may obtain a blessing” (1 Peter 3:9). Underlying such a posture is confidence in the Lord’s justice and coming vindication, supported by Peter’s citation of Psalm 34 (3:10-12).

While they might mention Christ’s suffering, rebellious spirits from the days of Noah, and the salvific character of baptism, 1 Peter 3:18-22 is not immediately about any of these subjects. Rather, the way that it is framed suggests that it is a passage about faithful Christian suffering.

3:18-22 develops Peter’s discussion of Christian suffering, by placing it in a more pronounced apocalyptic or eschatological framework, presenting a more developed analogy between the days of Noah and those of the Christians to whom Peter writes. It makes clear that Peter is not merely making a perennial point about righteous sufferers being finally rewarded and vindicated by the Lord. Peter will press further into this framework in chapter 4 of his epistle: “The end of all things is at hand; therefore be self-controlled and sober-minded for the sake of your prayers” (4:7). Such an analogy between Noah and the Flood and the judgment to be brought by Christ is found elsewhere, most notably in the Olivet Discourse (Matthew 24:37-39). Peter draws a similar analogy in his second epistle (2:4-10).

The analogy with the Flood is not incidental but is a key to 1 Peter 3:18-22. It is a means by which we will make better sense of the details of the passage, not least among them Christ’s preaching or proclaiming to the spirits in prison and Peter’s description of baptism. The analogy Peter is drawing is a broad one, with baptism only being one part of the larger picture. It is this analogy that gives coherence to the text. The parallel with the Flood provides a larger framework within which the hearers of the epistle might situate their experience, especially their suffering.

Notably, Peter doesn’t merely present us with a parallel between the Flood and Christ’s work, but with a direct connection between the two—following his death Christ proclaimed to the imprisoned spirits of Noah’s day. The singling out of these imprisoned spirits seems to require some explanation: why should Christ proclaim anything to them in particular? Why should Peter mention this event in this context? How is it that Peter can reference Christ’s proclaiming to the spirits in prison, an event that is not mentioned in any of the gospels, seemingly in passing and without further elaboration?

The most natural impression is that events prior to the Flood provide explanatory background in some sense for the work of Christ. Indeed, that a fuller understanding of both the work of Christ and the antediluvian history would reveal Christ’s proclaiming to the spirits in prison to be an event that relates closely to what we know of Christ’s work more generally, rather than being a strange and random event concerning which the rest of the New Testament is entirely silent.

Reading such a text, we should also consider how the first hearers of the text would have heard it. When they heard of the ‘spirits in prison’, what would have come to their mind?

There is not a ready explanation for why Christ might proclaim his victory to imprisoned antediluvian human spirits. Given the reference to angelic powers in the context, it seems more natural to take it as a reference to demonic beings. An apparent structural parallel (see above) between Christ’s ascension and the placing of angels, authorities, and powers under him in verse 22, and his preaching to the spirits in prison in verses 19 and 20, while by no means decisive, adds some weight to the identification of the ‘spirits in prison’ as rebellious angels.

The missing piece, as many have noted, is provided by the book of Enoch, a non-canonical pseudepigraphal intertestamental Jewish text (the relevant parts of the book likely dating from around 300-200BC). Enoch was a familiar text to many in the early Church and seemingly alluded to or cited at several points in the New Testament, most notably Jude 14-15, which appears to be a quotation from 1 Enoch 1:9.

The earlier parts of the book of Enoch speak of fallen angels or Watchers, who had sexual relations with human women, producing the Nephilim or giants, figures that some have associated with legendary heroes. Among other things, these fallen angels taught humankind technological skills, enchantments, astrology, cosmetics, and the use of roots and plants. As a result of their rebellion, the Lord then judged the world, imprisoning the fallen angels in darkness and bringing a Flood upon mankind, saving only Noah and his family.

The book of Enoch clearly advances an interpretation of Genesis 6:1-2, 4:

When man began to multiply on the face of the land and daughters were born to them, the sons of God saw that the daughters of man were attractive. And they took as their wives any they chose…. The Nephilim were on the earth in those days, and also afterward, when the sons of God came in to the daughters of man and they bore children to them. These were the mighty men who were of old, the men of renown.

The book of Enoch’s interpretation of Genesis 6 is attractive, helping to explain and fill out several features of the text. Understanding the ‘sons of God’ to be heavenly beings, rather than the supposed covenant line of Seth (the principal alternative reading), is the more natural reading of the expression (e.g. Job 1:6; 38:7). It explains the origins of the Nephilim or giants as arising from unnatural relations between angels and women. It helps to explain why the sexual relations are gendered as they are (‘sons of god’ with ‘daughters of man’, in a way that is strange if more general intermarriage between some covenant people and non-covenant people were at issue (e.g. Genesis 34:9; Nehemiah 10:30). Likewise, it helps to explain the severity of the action of the sons of God, that they were engaged in nothing less than a rebellion in the heavens.

The homology between the book of Enoch’s understanding of the events of Genesis 6 and the Fall should also be observed. The rebellious sons of God who gave humanity forbidden knowledge beyond their capacity for faithful mastery are akin to the Serpent of Genesis 3 and his offer of knowledge that would make Adam and Eve like the gods. Likewise, the action of the sons of god in seeing the beauty of the daughters of men and taking them is akin to the action of Eve in Genesis 3:6. Like the first Fall of mankind, the prediluvian rebellion is a rebellion of both angels and men.

In Genesis 5 we hear that Enoch “walked with God and was not, because God took him.” In the book of Enoch, Enoch is sent to proclaim to the rebellious Watchers, the fallen angels, their condemnation. This, some have argued, provides a very important background and parallel to Peter’s teaching in our passage, where Jesus does the same thing: just as the ascended Enoch once preached God’s condemnation to the spirits in prison, so Christ, in decisively defeating Satan’s purpose, declared that victory to the angels who had led the great rebellion. This would make a lot more sense: as Christ decisively frustrates the purposes of the rebellious angels, he proclaims his triumph to the great old adversaries. It also fits naturally with other elements of the context and with other New Testament teaching concerning Christ’s work, within which his exaltation over angelic powers and triumph over demonic rivals are greatly emphasized.

Many scholars have seen the story of the rebellious antediluvian angels alluded to in Jude 6: “And the angels who did not stay within their own position of authority, but left their proper dwelling, he has kept in eternal chains under gloomy darkness until the judgment of the great day…” Also in 2 Peter 2:4-5: “For if God did not spare angels when they sinned, but cast them into hell and committed them to chains of gloomy darkness to be kept until the judgment; if he did not spare the ancient world, but preserved Noah, a herald of righteousness, with seven others, when he brought a flood upon the world of the ungodly…”

While it is possible that Enoch and these texts had a common source that has been lost to us, the widespread knowledge and positive reception of the book of Enoch in the earliest post-apostolic Church make it the most plausible source by far. Indeed, if Peter did not mean to refer to the book of Enoch, it would likely have been necessary to add further clarifying remarks. Doubtless there are challenging questions about how to handle seeming references and allusions to such an influential non-canonical text in inspired Scripture, but the difficulty of such questions cannot excuse a denial of the evidence.

At this point we should step back from the text and consider how the pieces might fit together.

Peter’s purpose is to present a framework within which the suffering of the Christians to whom he is writing will make greater sense. He does this by situating their suffering as a suffering after the manner of and as a participation in Christ’s suffering. Like the Flood of Noah’s day drowned the old rebellious world, Christ’s suffering brings judgment upon an old epoch and initiates a new one (e.g. 2 Peter 3:5-7).

As with the first Fall, the rebellion that led to the Flood was first instigated by angels leading humanity astray and offering forbidden knowledge. Christ’s work is cosmic in its scope and, as we especially see in Revelation, a decisive victory over rebellious spiritual forces and reordering of the heavens and their powers. Christ’s work represents both the destined judgment of the present evil age and the passage into the new—both the Flood and the Ark.

When Peter speaks of Baptism now saving us, the comparison that he is chiefly drawing is between the construction of the Ark prior to the Flood, while God’s patience waited, and the construction of the Church in Christ through Baptism. The Church is formed as one body through baptism into Christ. It will be saved through the resurrection of Christ, who is the Ark into whom we are being gathered.

Peter’s larger point, then, is that Christian suffering needs to be understood within such a frame. Such suffering is a result of the inhospitality of this present evil age of the flesh to the righteous. It is also a passage through which we must pass to the spiritual age that is to come, much as Noah and his family had to endure the Flood. Christians suffering persecution suffer after the model of their Master, Jesus Christ. Our suffering is not interminable, but awaits a decisive reversal as final judgment will come upon the wicked. Baptism is part of the preparation for the passage that we must undergo. In it we are formed together within Jesus Christ, as the true Ark. Our watery Baptism proclaims and is a promissory anticipation of the passage that Christ has already undergone and that we will undergo in him. Behind all we experience is a greater spiritual battle, in which Christ’s victory over rebellious angelic powers is being accomplished.

Susannah: This is all very well, and I don’t disagree, but there are specific questions that many aspects of this whole approach brings up. Let me name a few:

This is really very supernatural indeed. Angels, aka the beings elsewhere referred to in the OT as small-g gods, having sex with and impregnating human women? Their kids being giants/mighty men of reknown? This sounds very much like what happened with, say, Zeus and Leda, or Zeus and Alcmene, or Aphrodite and Anchises, which led to the birth of, for example, Herakles/Hercules, and Aeneas, etc etc. In general, this is starting to sound a whole lot like Hesiod, to a disconcerting degree.

What are we supposed to think about texts like Enoch? Protestants tend to have a very clear-cut way of thinking about ancient texts as either inspired scripture, or apocryphal fables. This seems to imply that things are more complicated.

What about UFOs, though.

Soulcraft as the Beginning of Statecraft

Alastair: The most significant books in our lives are often those that help us to consider and to change some of our more fundamental habits of thought and practice. The effect of such books is not narrowly confined to a specific realm of knowledge or action, but is more comprehensive and ecological, their insights leavening our lives much more broadly.

One such book for me has been A Failure of Nerve: Leadership in the Age of the Quick Fix, a posthumously published work of the family therapist Rabbi Edwin Friedman.

A Failure of Nerve characterizes itself as a leadership book. While not inaccurate, this invites misleading assumptions and might narrow readers’ attention. Leadership is typically imagined as how we manage other people, yet Friedman’s core insight is that leadership must arise out of our mastery of ourselves. Healthy leadership, Friedman maintains, recognizes and avoids the reactivity of poorly differentiated societies. It is about developing selves with healthy boundaries, enabling us to relate and respond to the world and others around us, rather than chiefly reacting to them. We have likely missed the deepest point if we read Friedman and come away thinking about how much we need to apply his insights to other people.

Friedman’s core insight is a simple yet immensely powerful one, bringing clarity to various realities discussed by other authors and even within Scripture itself (see my thoughts here for one such example). Understood well and practically applied, this insight sets us out on a quest for mastery over ourselves, by which we will be enabled to act in a self-determined yet engaged way, rather than out of an unhealthy emotional entanglement with others and the situations around us.

Friedman’s insight also helps to bring features of a biblical ethic into greater clarity and helps us to identify how it diverges from many of the dominant postures of action and imagination that surround us. For instance, in a manner greatly accentuated by the influence of social media, there is a growing tendency for people to forge their sense of selfhood within broad political movements and in terms of perceived social forces. In a recent New York Times article, the psychologist Orna Guralnik observes:

[I]n my practice, I’ve found that engaging with these progressive movements has led to deep changes in our psyches. My patients, regardless of political affiliation, are incorporating the messages of social movements into the very structure of their being. New words make new thoughts and feelings possible. As a collective we appear to be coming around to the idea that bigger social forces run through us, animating us and pitting us against one another, whatever our conscious intentions. To invert a truism, the political is personal.

The extreme porosity of such selves to social forces can, as Clare Coffey argues in her essay “Failure to Cope ‘Under Capitalism,’”, result in a sort of abjection, an abdication of agency and responsibility, self-exculpatory indulgence of personal vices, the cultivation of ressentiment, and a ‘subsuming’ of personal sufferings into a continuum of collective experience. Where the personal and the political have become so undifferentiated and conflated, people can become so fixated by the deep imperfections of their society that they fail to develop responsibility and agency where and how they can.

Persons formed in such movements (which can truly be found across the political and ideological spectrum) can develop senses of self against the foil of a malign, immensely powerful, yet diffuse social agencies that are their relentless antagonists. These might be the Patriarchy, Liberalism, Capitalism, ‘Wokeness’, or any number of other imagined or real social forces. Faced with such immense perceived forces, a posture of protest, ressentiment, resistance, rebellion, grievance, moral abjection through the extreme assumption of collective guilt, or victimhood can be internalized to the point of becoming integral to the self.

However, the undifferentiation of the political and the personal produces selves that have so internalized or postured themselves against social forces that they have not properly developed their personal agency and responsibility. While such social forces certainly exist and matter, and none of us are immune to them, there are few things more dangerous than to allow the existence of such forces to distract or excuse us from the task of developing our personal agency and responsibility.

The posture I am describing can result in a familiar mode of politics and forms of character. Such politics, focused upon holding others accountable, upon loudly identifying others’ sins, upon petitioning and demanding that other agencies act on our behalf, etc. can form irresponsible, unaccountable, dependent, bitter, weak, and angry people, who find their morality in proclaiming others’ sins and their agency in entitled dependency. Such persons can be resistant to searching self-examination, because identifying other people’s sins is just too urgent a priority. Alternatively, the lack of self-differentiation can produce the crippling political masochism, self-flagellation, and abjection of persons who have internalized extreme forms of collective guilt, lacking any capacity to appreciate where such accusations might overreach.

In contrast to the selves forged in contexts where the personal has been allowed to become undifferentiated from the political, Friedman’s approach emphasizes our need to develop ‘self-differentiation’, boundaries between ourselves and the relational, social, and political forces that surround us. We must take true responsibility, while also being able to protect ourselves from the false responsibility that others can place upon us. We must develop our own agency and hold ourselves accountable for our actions. We must control and take ownership of our responses to other people’s actions towards us, overcoming our impulse merely to react. True leadership, Friedman maintains, is downstream of such self-mastery.

Good leaders and healthy movements act like prospective incumbents, even when they are a marginal opposition, faced with immense contrary social forces. They start by holding themselves accountable. They are chiefly concerned with developing their own agency, rather than accusing others for not acting on their behalf. Even when wronged, they don’t live by bitterness or blame. They are far more concerned to deal with their own sins and to grow in righteousness than they are to identify and fixate upon the sins of outsiders. They try to minimize the amount of their mental real estate they permit their opponents to occupy. While not blind to powerful social forces and the structural aspects of injustice and power, and while willing to address them, their concern is to do what they can to develop and extend a well-defined realm of personal responsible agency.

I’ve noted the ways that narrative templates of revolution, countercultural movement, resistance, transgression, victimhood, or extreme internalized guilt, have taken over many people’s imaginations, across the political spectrum. As they operate, such narrative templates can encourage or cultivate parasitic virtue: morality via accusation of others, a false responsibility of holding others accountable, an ‘agency’ of pushing for others to do things for us, of regarding ourselves as victims.

It is, however, one thing to recognize the importance of self-differentiation and overcoming our reactivity; it is quite another actually to master ourselves and to learn how to respond, rather than chiefly reacting. For me, it was within a Christian understanding of my self and my agency that such development opened up.

The Christian faith offers a radically contrasting template to all. We are royalty in Christ—sons and daughters of the King. We learn to live as rulers, even when in cultural opposition, mastering our own spirits and holding ourselves and communities accountable, rather than living by blaming others. Ressentiment and bitterness are poisonous and have no place; we practice the forgiveness of others as God himself has forgiven us. We pursue confident magnanimity. We must learn to suffer as kings and queens, much as David did before he was exalted to the throne. We must love our enemies. We must turn the other cheek.

If we are those who can truly exercise rule faithfully, we will be learning to act as incumbents and as responsible powerful persons our whole lives, not merely seeing this as something that comes at the point when we finally take power away from our opponents, when the contrary social forces have been overcome, when the revolution succeeds, or when we have finally been absolved of the sins of our fathers.

People who operate in such ways will seldom rule well. The habits of parasitic morality are so deeply instilled that they will always be projecting some vicious bad guys against which they can characterize themselves as the good guys. Without such a projected foil, their ‘virtue’ dissolves. Even when they hold the highest offices, they will still be imagining themselves as ‘speaking truth to power,’ or something like that. They will still act as resentful and entitled dependents who need other people to act on their behalf. This is a form of rhetoric and action at least as common on the political right as it is on the left

Likewise, we must beware of the way that we can use the foil of some (typically caricatured) opponents or perceived social forces to deflect attention from, abdicate responsibility for, resist judgment upon, or avoid the task of developing agency within the realm of our own actions. A preoccupation with such foils are a powerful obstacle to personal and communal growth to maturity, to truth, and to responsible agency. If you are reading this chiefly as an important lesson for your political opponents, you are misreading it. This must always start with our own selves.

As Christians, while not blind to powerful contrary forces, to antagonists, and to injustices within our lives and societies, we must learn to think and act confidently as potential martyrs, not as impotent and resentful victims. We must always first address the beams in our own eyes, rather than being blindly preoccupied with removing them from others’. We must learn to act as gracious kings and queens, focusing upon and chiefly living out of the authority that we have in Christ. We must learn self-mastery and develop our capacity for responsibility. This is especially important in a society where prevailing cultural forces in most quarters are so contrary to this. In so doing, whatever our success in our social and political ventures, we will at least have defended and built up our own souls. And the spiritually healthy politics that we so desperately need is downstream of this.

Happenings and Doings

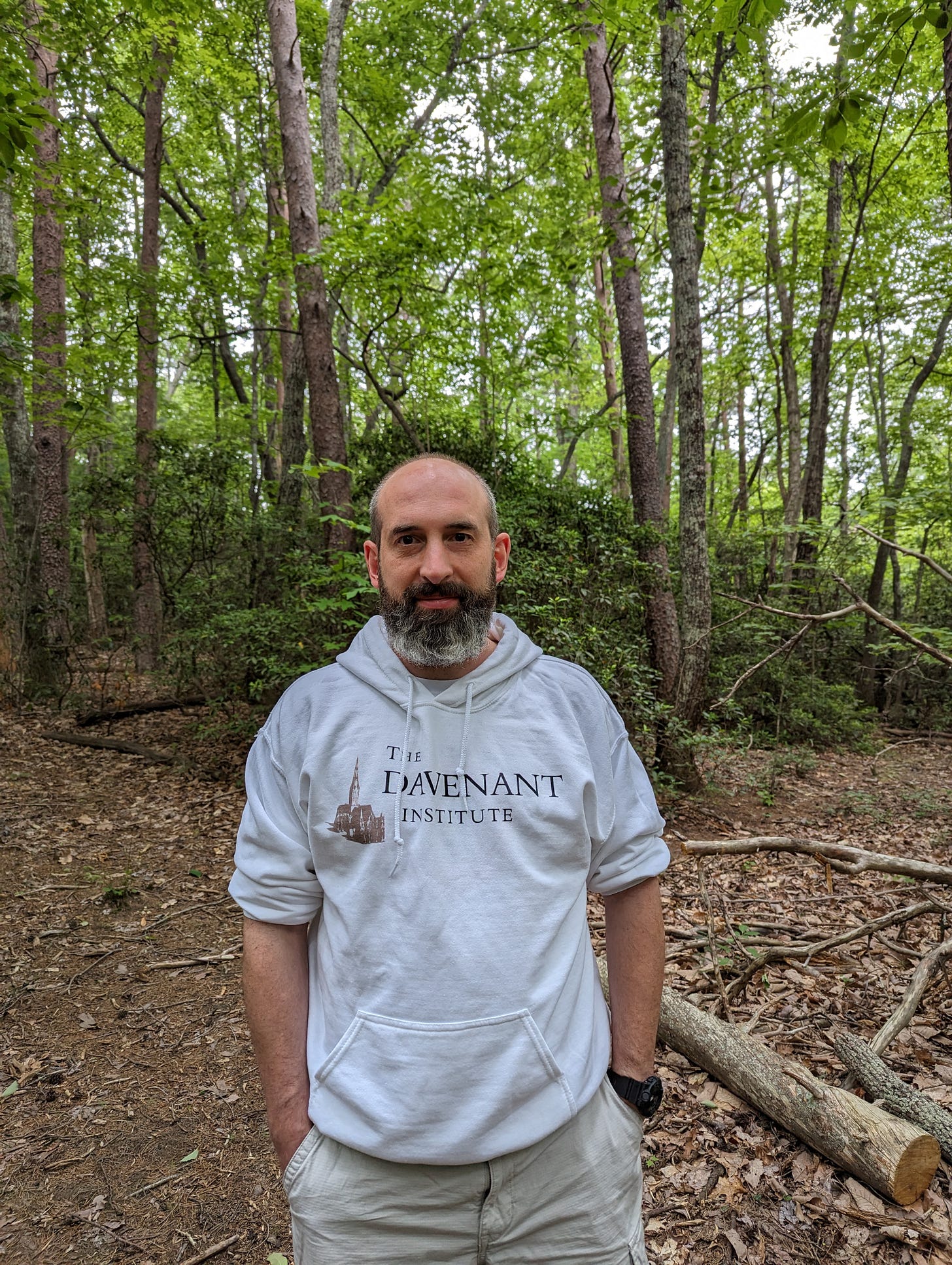

Alastair: The last couple of weeks back in the US have been packed. On Tuesday 30th, we took the train down to Washington DC, as the first stage of our journey down to Davenant House for the annual Convivium. This Convivium was the tenth and the largest to date. As I hadn’t attended the Convivium since 2019 and several good friends were attending, I was especially eager to make it this year.

Starting very early on Wednesday morning, we drove down to South Carolina from DC. The journey to Convivium has always been one of several highlights of the event for me, offering an extended opportunity for conversation and discussion. When you pass the Gaffney Peachoid on the road, you know that you are nearly there!

Convivium is a unique experience. The children of the friend who drove us down described it as ‘theology nerd camp’, which pretty much captures it. There are a few days of thoughtful lectures and intense conversation, with a group of about 40-50 others. It brings together pastors, scholars in the mainstream academy, teachers and theologians in seminaries and Christian education, and several interested lay persons.

The Davenant property is peculiarly conducive for such conversation, with several nooks and niches, porches and tables, corners and couches, fire pits and forest paths into which discussion spills over and disperses between the sessions and carries on late into the night. Chores and accommodation are shared and days end with shared worship. Over the course of a Convivium one will typically speak to most other attendees on several occasions. The atmosphere of Convivium is one of the things I most appreciate, manifesting the ethos and sort of discourse that has always been distinctive of Davenant as an organization. The variety of people at Convivium, the openness and curiosity of so many of the attendees, the generosity of people in their scholarship, the smaller numbers, and the more intimate and shared living space, mean that you can have conversations at Convivium that it would be difficult to have anywhere else.

The Convivium this year was entitled ‘Christ and the Nations: A Protestant Theology of Statecraft’, addressing questions of political theology. Eric Gregory was the keynote speaker. Although I had to miss a few talks due to teaching and podcasting commitments, it was a stimulating few days and it was wonderful to catch up with several old friends and to make a few new ones. I delivered a talk on the subject of the biblical theology that underlies coronation, exploring the theme of sovereignty throughout the Old Testament and how the entire New Testament could be read as an account of Christ’s coronation.

The Convivium ended last Saturday, but we stayed on for the Davenant Staff Retreat that followed. Last Sunday, I was invited to preach at a local church on 1 Peter 3:13-17, so passed a relaxing Saturday, setting aside some time for preparation.

The Staff Retreat was very encouraging, providing us with our first opportunity to meet with several colleagues and members of Davenant’s board, while taking stock of the past year and strategizing for the future. Being involved with Davenant has been an immense blessing over the past decade. At the heart of the organization are a remarkable group of faithful Christians, whose commitment to encouraging Christian scholarship for the upbuilding of the church and as a witness in the academy has borne great fruit. Seeing Rick and Beth Littlejohn and Brad and Rachel Littlejohn and their children has reminded me once again of the debt of gratitude that we owe to them for their work, sacrificial commitment, and generous hospitality for this cause. Davenant is an organization that we hope to be involved with for decades to come; it is doing astounding work with a limited budget and is worthy of a much higher profile and support.

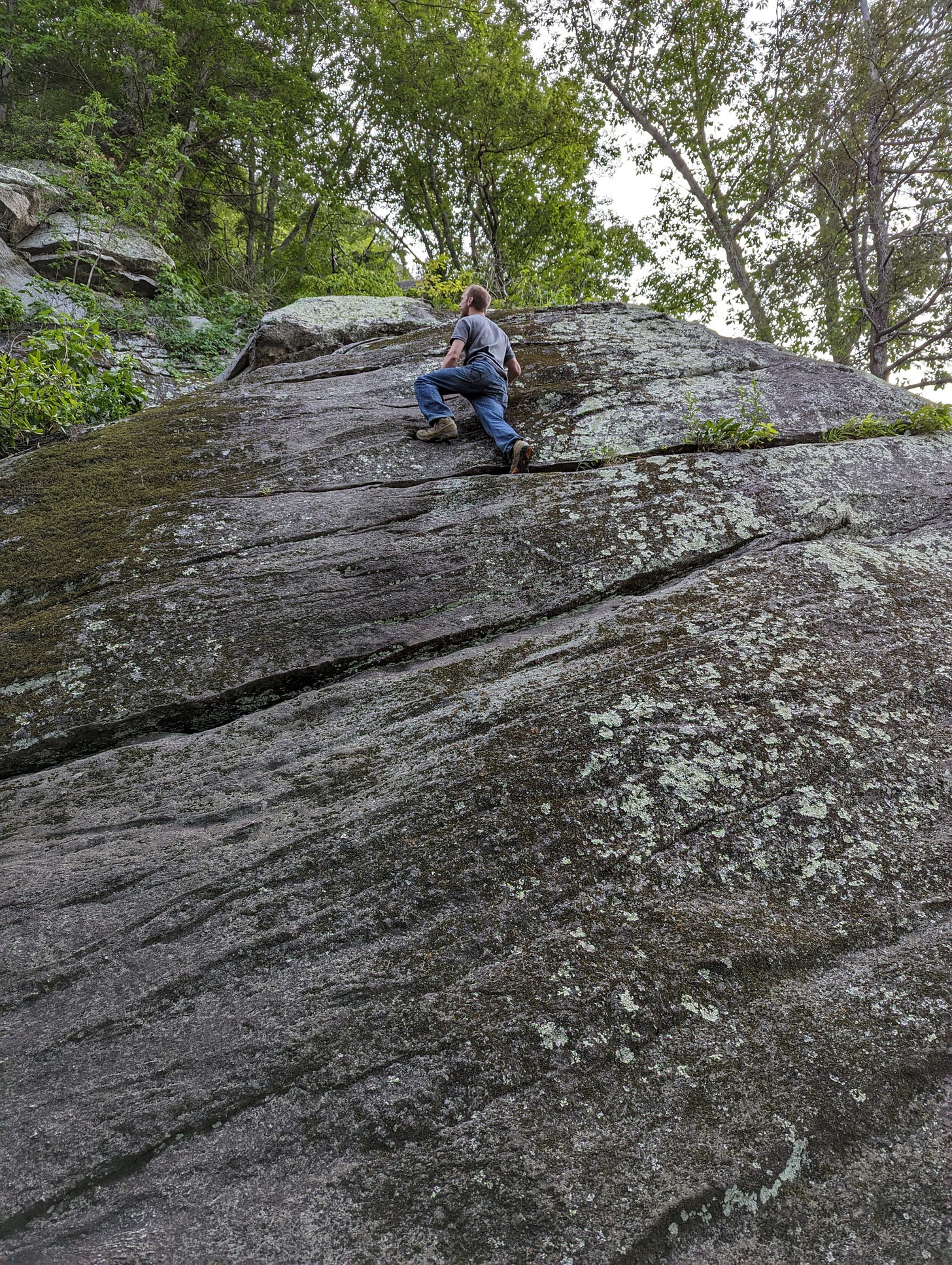

During the Staff Retreat we visited Chimney Rock State Park near Lake Lure. We climbed up to Chimney Rock, a spectacular granite monolith, almost 100m high, on whose top a large American flag flies. We also explored some of the other nearby routes. The routes themselves were relatively easy but the views from the various vantage points were breathtaking. After the walk we reconvened at the bottom of the route for a meal.

Another highlight of the Staff Retreat was the trivia quiz that Brad produced for the group. Susannah and I were split up and it looked certain that my group was going to win until we were sunk by rounds on classical music and Jane Austen, and a bonus round in honour of Rick Littlejohn’s birthday. Susannah also fired a real gun for the first time.

The Staff Retreat ended on Wednesday and the rest of the week was more relaxed, offering a chance to catch our breath after a week of intense social activities. Susannah had been due to fly back to New York on Wednesday, but the air pollution after the Canadian fires meant that she had to wait until Friday to do so. We were very thankful for the extra couple of days!

After Susannah left on Friday, I joined the Littlejohns for a visit to some friends at Lake Lure. We spent the afternoon out on the lake, where I attempted—without any success, but to the amusement of onlookers—to waterski for the first time. Saturday was another relaxed day for me, giving me the opportunity to catch up on more reading and to prepare my sermon for Sunday morning.

Susannah is back in New York, preparing for our house move. I have a busy week ahead, catching up on a backlog of work and preparing for the course I’ll be teaching here the following week. My Davenant course on a Biblical Theology of the Sexes also concludes this week. The Littlejohns saw a bear a few days ago, so I’m hoping to see one before I leave. I have seen bears here a couple of times before, but I have only seen lots of squirrels, a few deer, and Rosetti the cat this time.

Recent Work

Alastair

❧ Pastor Tim Keller, who recently entered into glory, was an immense influence upon and force behind the work of many of us. He was also a long-term friend of our Mere Fidelity podcast. Jake Meador joined Derek, Matt, and me for a discussion of Keller’s life and legacy. Reading is an essential aspect of our work for all of us on Mere Fidelity. In our latest episode we discuss how people might improve their reading, so that they might do it more thoughtfully and fruitfully.

❧ Our latest two episodes of the Theopolis Podcast continue our Deuteronomy series. The first is on Deuteronomy 8—Remember the Lord Your God. The second is on Deuteronomy 9—Not Because of Your Righteousness.

❧ The story of Jephthah’s vow in Judges 11 is an unsettling narrative that divides commentators. Samuel Delgado of the Weird Christian Podcast invited me to join him for an episode on the story.

❧ I’ve preached the last two Sundays at Grace Foothills church in Tryon. Last week was on 1 Peter 3:13-17 and this week was on 1 Peter 3:18-22. I also delivered an hour-long talk at the Convivium on the biblical theological background for understanding coronation.

Upcoming Events

❧ Alastair will be in Birmingham at the Theopolis Ministry Conference and the subsequent Fellows’ Programme next month.

❧ Alastair is one of the speakers at a conference on a Protestant Theology of the Body on September 9th.

❧ We are moving over the next two weeks. Please pray that everything goes smoothly!

❧ Most of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Susannah and Alastair

Hello 👋, I'm one of your subscribers. My name is Oliver. Obviously yours are Susannah and Alastair. It's nice to meet you. As to who all we subscribers are, I can't say. I can't even say who I am anymore. I would suggest maybe reaching out to Cambridge Analytica for answers.

Wonderful treatment of Peter here. As far as concerns over similarities to tales of the Greek demigods, I recommend reading Heiser. He asserted that Genesis 6 was really a polemic, in that the ancient Mesopotamians had Gilgamesh and other Nephilim and their fathers as the good guys. Moses has them as the villains.