№ 8: New Year

Improving biblical recollection, text and paratext, the Baptistic flavouring of American politics...

Dear friends,

I’m writing this from the living room at Davenant House, where Alastair will be, for the next two weeks, be teaching 20 hours worth of classes, which sounds like a lot, to me. I’m here for the first week. I’ve been involved in The Davenant Institute for probably a decade, it’s sort of how Alastair & I met, I’ve been on the board for maybe three terms?? I edited the magazine for a while, I think I may still be an editor for Davenant Press, I’ve organized conferences, but I have never been to the place itself.

To see this place and witness the work of an institution that I’ve seen grow, and have helped to cultivate, is extremely inspiring. So that’s very cool.

We’ve been busy since Christmas! But also everyone has been sick, so a lot of the busyness has been tending to people. Alastair & my mother & my brother & my father & my stepmother all got COVID, and everyone seems to be either entirely mended or well on their way. My sister-in-law and I dodged it somehow.

We did find time to have a blast on New Years’ Eve with friends. For more details, see Alastair’s rundown below.

We also, as Alastair mentions below, have developed some big 2023 plans, some of which involve Davenant, which you will be hearing about here over the next couple of months.

Improving Biblical Recollection

Alastair: On Friday, I started teaching my new Davenant Hall course on the art of biblical literature. A primary purpose of the course is to improve students’ facility in the reading of biblical narrative, as they become more attentive to the artistry of the text. A secondary benefit of such study is that it can greatly increase biblical comprehension and recollection. It is through the recognition of patterns, motifs, structures, and other such things that growth in biblical knowledge can become more exponential than linear in its character.

While many people think about memory as if it were primarily additive, with discrete fact after discrete fact being brought into and retained in our knowledge, memory, at least in my experience, is mostly about the connections between such facts. Memory is about creating meaningful clusters, chains, and networks of details in our knowledge. Having such larger structures and patterns in mind, we will be able to move smoothly between details in our knowledge and even recreate them when they have been partially forgotten.

Let me give some examples of what I have in mind.

In a recent post here, I discussed Exodus 25-31’s instructions for the tabernacle as two cycles of creation days. Being alert to the presence of this pattern, we will better perceive the meaning of the tabernacle. However, even when not instantly able to recall the order of the instructions for the tabernacle, with the seven-day pattern as a mental prompt, we will be able mentally to reconstruct that order in under a minute. And having several patterns in mind will help us further: in the case of the instructions for the tabernacle, for instance, I also think of the gold-silver-bronze sequence for the first three groups in both cycles.

You can do something similar with things like the Ten Commandments, or the ten plagues. Know the patterns and you can mentally reconstruct a lot. For instance, the Ten Commandments are split into two tables of five—the first set is vertical (God and parents), and the second set is horizontal (one’s neighbour). The first three commandments deal with a progression of forms of idolatry: 1. worshipping a different god; 2. worshipping with idols; 3. bearing God’s name in vain. The final five commandments are a progression of attacks upon persons: 1. killing; 2. taking spouse; 3. taking property; 4. attacking name; 5. coveting.

While I have criticized overdependence upon chapters and verses, they can help to map out the spread of material in many books. Knowing the number of chapters and the events of key chapters in most books, you have a grid within which you can mentally reconstruct their contents. This is even easier when you have a sense of larger narrative and textual structures within the books in question.

Literary and narrative patterns that unite stories can really help with sequencing. For instance, if you know Genesis 18 and the visit of the angels to Abraham forms a diptych with the visit of the angels to Sodom, you can remember the order of the stories and key elements within them. Patterns also help to highlight differences and divergences. You won’t so easily confuse the three stories of Sarai and Rebekah being taken by pagan kings, for instance, if the common pattern has also alerted you to the differences between the stories.

Typological motifs help here too. If you know Genesis 19 follows an Exodus pattern, you’ll find it considerably easier to remember many details: the number of the angels, the meal that they eat, the location of the threat, the site to which they flee, etc. There are numerous examples of this.

The more familiar you are with the text more generally, the more unusual details will stick out. You’ll recognize phrases or details that are only found in a couple of locations. And those details, since they connect stories, further strengthen your recall of them. So, for instance, it is easier to remember something like the story of Samson when you know related narratives and patterns: similarities between Judges 14 and Genesis 38, how Delilah’s tests recapitulate Samson’s heroic acts, and connections between the silver in chapters 16 and 17.

Knowing the symbolic or associative force of certain details helps. I can remember the ages of many biblical characters for this reason. Anna was 84 (7x12). Jairus’ daughter was 12, as she is associated with the woman with the issue of blood for twelve years. Joseph and Joshua both live to 110. Ishmael, Levi, and Amram all live to the age of 137. Sarah shares her age with the number of Persian provinces during the reign of Ahasuerus. The ages of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph follow a mathematical sequence. Many other such examples could be mentioned.

Chiastic structures can also help here. How do you remember the order of the stories in Daniel? It helps to know that chapters 2-7 form a chiasm (this will also help you to remember the section of Daniel that is in Aramaic). Chapter 2 and chapter 7, for instance, are paralleled in this chiastic sequence: the four levels of the image in 2 correspond with the four beasts in 7. The fiery furnace in chapter 3 pairs with the lions’ den in 6.

Knowing larger structures, patterns, and themes will also help you distinguish between the gospels, especially the Synoptics. For instance, Matthew structures his gospel as a recapitulation of Genesis to Chronicles. The Beatitudes with which Jesus’ public ministry begins in Matthew 5 are paralleled with woes that end it in chapter 23. Luke has a long journey narrative, which parallels with a Galilean ministry narrative beginning the gospel: witness by John/Peter, Baptism/Transfiguration, etc. This journey narrative also has chiastic structuring, e.g. Jesus talks about a man left by the side of the road from Jerusalem to Jericho and meets a man by the road from Jericho to Jerusalem, both in the near context of questions about inheriting eternal life. Once again, this is one example of a great many.

Further, there are structures overarching the entire Scriptures: things like the priest to king to prophet pattern James Jordan identifies, or the familiar movement from the garden to the garden city, with elements of Genesis 1-2 reappearing at the end of Revelation.

Reflection upon the logic of ‘systems’ helps. For instance, if you know the sabbatical structuring of Israel’s year and other underlying principles, it isn’t hard to remember the timing of all the feasts, as much can be mentally reconstructed from those principles. Similar things could be said about the measurements of the tabernacle and the temples, the manner of the sacrifices, the ordering of many books, etc., etc.

The fact that work on literary, symbolic, and typological features of Scripture can turbocharge our levels of biblical recall is one of many reasons why I am so personally invested in this.

The Baptistic Flavour of American Politics

Alastair: Recent remarks by David Henry about analogies between Baptist understanding of the Church and classical Greek understanding of citizenship sparked some thoughts about the more Baptist flavour of American politics and a potential ‘steelmanning’ (the opposite of strawmanning) of a distinctively Baptist politics.

The Baptist emphasis is upon informed, accountable, committed, believing, mature individuals being the full members of the community, responsible for directing it and maintaining its character. The form of polity rests heavily upon the spiritual freedom and agency of individuals. This is somewhat homologous to a republic heavily emphasizing the distributed sovereignty of an informed and responsible citizenry.

Whereas other ecclesiologies may stress a more ‘aristocratic’ or ‘monarchical’ authority of ministers or popes, Baptist polity centres the congregation. In Baptist polity, the locus of authority is a lot more popular and democratic, driven by appeals to founding principles and texts, approached with differing hermeneutics. Power depends upon the shaping of congregations’ collective judgments. Urgent rhetorical appeal to the public is central.

Without the same strong ecclesiological structure, Baptist thought is directed far more powerfully by a vast ‘para-ecclesiological’ structure, of conferences, popular-level publishing houses, mass media, celebrity figures, Christian musicians and artists, etc. Popular Christian ‘culture-makers’, while exerting an influence in other Protestant and Catholic circles, are most powerful in Baptist ones. As authority is less institutionalized, there is a lot more that is up for grabs and contested.

Further, as identity is less ‘given’ it is at once more open to newcomers but also much more performative. The truth of someone’s faith must be tested, demonstrated, and vocalized. Are you really a believer? You need to show and prove it, being outgoing and expressive of it. American identity is much less ‘given’ than it can be in other countries and much less tolerant of ‘nominalism’. You have to believe in it and ideally perform and publicize your American identity, not merely for the security of your own status, but for that of the polity.

It seems to me ‘culture’ occupies a different political position in the US than in most other countries, being a far more dominant locus of authority. Control of ‘the culture’ is highly contested and those who dominate it have much more power, even if they don’t control the government.

This is not the place to do justice to the scale and scope of what has occurred, but America’s history has coincided with dramatic and far-reaching transformations in cultural media. The steam printing press, the telegraph, the telephone, the radio, various technologies of recorded music, the television, the Internet, and social media have all had the effect of integrating centralizing, and unifying American ‘culture’, weakening the power and production of local culture and creating a ‘society’ that functions as a vast market of impressionable cultural consumers, catered to by industrialized agencies of cultural production. The sort of thing that the words ‘the culture’ names is vastly different from what they would have named two and a half centuries ago. The political shift that these developments represent should not be missed. People rightly recognize that the ideological tendencies and the ‘representation’ that a company like Disney embodies and offers have weighty political import.

Nominalism or apostasy from national faith are more threatening to what we might call a ‘gathered nation’ polity (recognizing the ‘gathered church’ analogy). America isn’t just a ‘creedal nation’ as some say, but a sort of common national faith is peculiarly prominent within it. America is also less ‘established’ and ‘institutionalized’ than other nations. Its institutions are more institutions of contestation concerning its creed and offices; it is constantly on the brink of potential reinvention. Cultural impulses are consequentially more determinative.

Without robust established structures and foundations of nationhood, the vast power of American culture operates similarly to the parachurch in Baptist cultures. It isn’t that other countries don’t have culture as a locus of authority; it just isn’t quite as determinative. The homologies between American political life and Baptist ecclesiology seems to me to involve a mutual congruency: being rather like each other, they are also somewhat suited for each other.

It seems to me this also highlights the possibility and tendencies of assertive Baptist politics. Where mass democratic culture is the principal locus of power/authority, a sort of Baptist politics will come more naturally. Politics is struggle for ‘the culture’, with a strong emphasis upon the formation of the everyman citizen upon whose shoulders the polity ultimately rests.

Understanding the baptistic tendencies of American politics would, I think, help bring various phenomena into greater clarity, not least the contrasting forms of public discourse in the US from somewhere like the UK. American public discourse, for instance, has much greater freedom from government imposition, yet much greater susceptibility to cultural pressures. Power comes from the middle, from the ordering of mass opinion, mass spectacle, and dominance of the mass market. As Tocqueville appreciated, this can produce a situation of the tyranny of mainstream opinion, which people in cultural power are always massaging, nudging, or shaping, while constantly flattering the public that it is forming its own judgments. Less room exists for dissent.

On the other hand, the vision of an informed, accountable, and committed republican citizenry, exerting their own responsible political agency in service of a highly internalized vision of a healthy commonwealth has an undeniable appeal.

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ Byrne Power invited me on the Anadromist channel for a wide-ranging discussion about imagination, the Bible, and time. I also appeared on the Anadromist New Year video discussing my experience of 2022 and my hopes for 2023.

❧ On the Theopolis podcast our discussion of James Jordan’s Through New Eyes continues. Over the last few weeks, we have discussed angels, the breaking bread pattern, and man as an agent of transformation. On the third of these, we explored Jordan’s priest-king-prophet paradigm, which is tremendously illuminating as a paradigm.

What We’re Reading

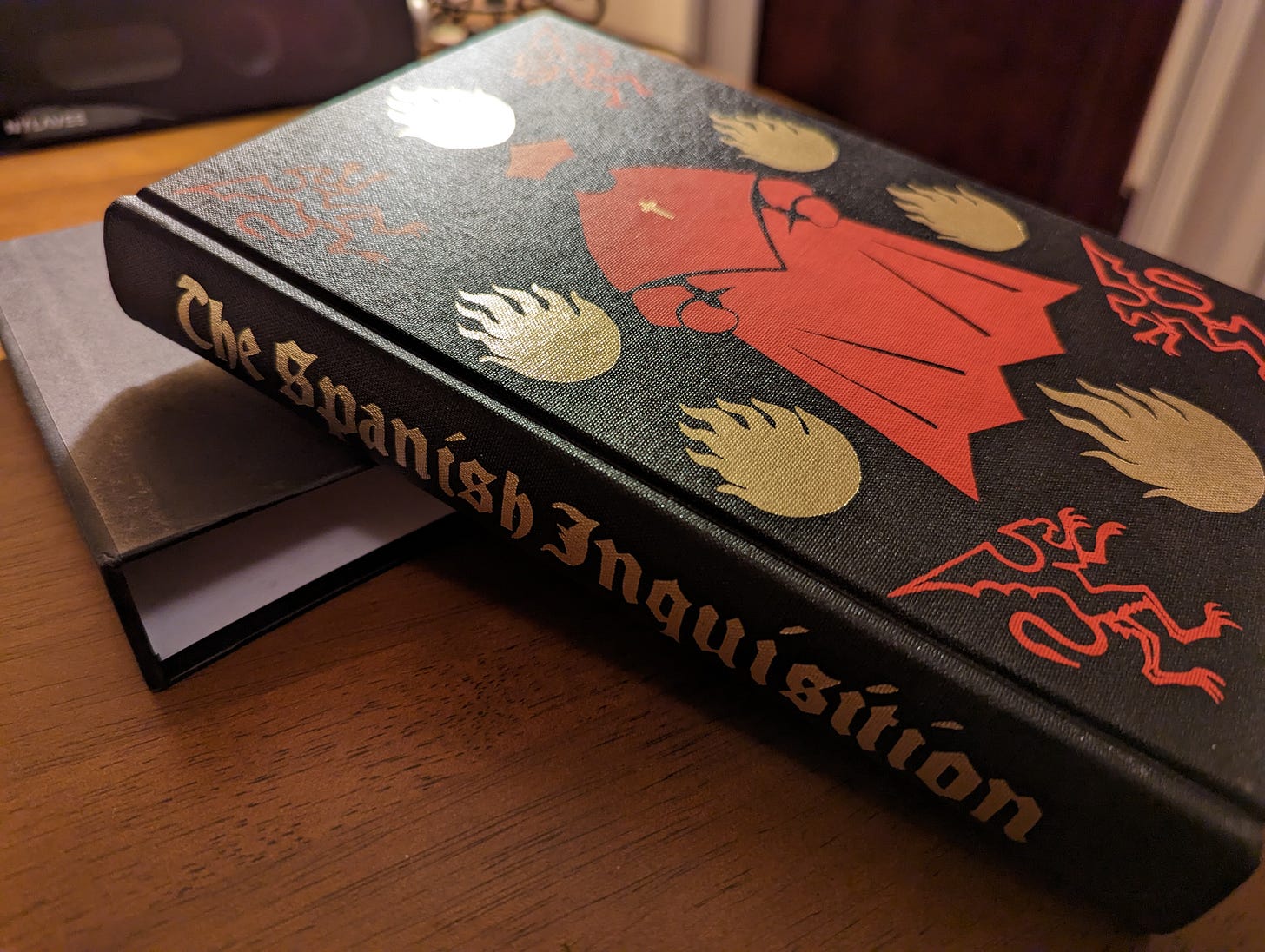

Alastair: Gregory Goswell’s recent Lexham Academic book, Text and Paratext: Book Order, Title, and Division as Keys to Biblical Interpretation, takes up a fascinating subject, exploring the manner in which features of our Bibles to which we have likely given little more than stray thoughts, nonetheless significantly colour our interactions with the biblical text. While much has been written about the composition of the canon, for instance, the structuring, division, and ordering of the books that have been included receives less attention. Yet, as Goswell recognizes, such ordering nudges readers’ interpretative judgments and has the effect of directing their gaze towards certain textual features and themes and away from others.

Placed alongside each other, books tend to strike up conversations. Within the Hebrew canon, for example, the book of Ruth can follow Proverbs and precede Song of Songs. Such an ordering has led many Jewish readers to see the figure of Ruth in the woman of Proverbs 31 and also to foreground the romantic aspect that it shares with the Song. On the other hand, our English Bibles, by placing the book between Judges and 1 Samuel, more accent the book’s historical settings—the way the book occurs in the period of the judges and anticipates the rise of the Davidic dynasty. Such interrelations between books have been an especial focus of study in treatments of the Book of the Twelve (the united collection of the so-called ‘minor prophets’). Goswell’s concern is not to argue that one such approach is better than the other, but to alert his readers to the interpretative decisions embodied and influence exercised by such paratextual features.

We could easily imagine entirely different ways of ordering the biblical books, according to very different principles. One such recent project is the four volume The Books of the Bible series (Covenant History; The Prophets; The Writings; New Testament), which, most strikingly, orders the New Testament books under four gospel families of texts: Luke-Acts and the Pauline epistles; Matthew, Hebrews, and James; Mark, 1 & 2 Peter, and Jude; John and the other Johannine texts—1, 2, & 3 John, and Revelation. Such an ordering invites us to consider the affinities within four distinctive bodies of witness that comprise the New Testament.

Different orderings of the text might respond to features of the texts themselves. For instance, Luke and Acts are perhaps best read as a two-volume work and, while they are separated by the gospel of John in typical Bibles, it can be helpful to read them together from time to time. I have mentioned the work of Warren Gage on the relations between John’s gospel and the book of Revelation before, relations that may also be unhelpfully obscured by their separation in our conventional canonical ordering.

Besides the ordering of books, Goswell discusses their naming. The names of biblical books are not inspired, yet, once again, are factors that can shape our reading. We could well imagine, as David Daube has noted, the book of Esther being named after Mordecai instead. Mordecai is introduced as if he were the principal character after the opening prologue in 2:5, whose refusal to bow to Haman precipitates the plot, and who dominates the concluding chapters. The naming of the book after Esther has the effect of placing her character centre stage, while Mordecai’s role is less noticed.

Goswell also discusses chapters, verses, and other such divisions, which have the effect of joining or dividing, highlighting or obscuring certain texts or features. For example, Mark 9:1 might appear to be a text orphaned from the discourse that precedes it at the end of chapter 8. However, placed where it is, immediately before the account of the Transfiguration, the reader is invited to read the event of the Transfiguration as, at least in part, a fulfilment of Jesus’s statement within it.

I found Goswell’s book thought-provoking and worthwhile, yet was also disappointed that several seemingly key aspects of the subject weren’t addressed, or only received cursory attention. Particularly helpful would have been closer consideration and discussion of the evolving ways in which biblical books have been ordered historically. Towards the end, Goswell gestured towards the impact of digital technologies in occluding the canonical framing of texts. Yet it would have been helpful to explore the way in which the ordering of books functioned prior to pandects containing all biblical books bound together in volumes. Peter Leithart has a fascinating essay arguing that the gospel of Matthew follows a careful historical sequence of Old Testament allusions that might have some light to shed upon the conversation here.

I’ve discussed chapters and verses on this Substack in the past. It is important to consider that they are largely novel developments (our modern system of verses dates from the 1550s) and the forms of textual division that precede them might hew somewhat more closely to sense units that are integral to the text as their purpose is more straightforwardly liturgical, serving more the public reading of the scriptures than their private reference. I would have appreciated a discussion of the ways in which paratexts might function differently for texts chiefly designed to be heard than they do for texts chiefly designed to be silently and privately read from a page. For instance, how do Hebrew cantillation marks (guiding a reader’s intonation of their speech in the chanting of a text) function paratextually, and how might an encounter with the text shaped by such paratextual features differ from the silent reader of a biblical passage divided by verses?

Anyone who pays attention to the choices of readings in historic Sunday lectionaries, for instance, will often be struck by insightful juxtapositions of texts, two or more texts that are brought into conversation in ways that produce arresting insight. Not least because they can place texts in parallel, not merely in sequence, lectionaries allow for profound intertextual dynamics to emerge and have been an important paratextual framing of the people of God’s experience of Scripture for millennia. I would have appreciated some discussion of this.

It also seems to me that the internal structure of the book of Psalms (and perhaps also Proverbs) merits far more extensive attention. James Hamilton has done pioneering work on the internal structure of Psalms in his recent commentary on the book, arguing that the five books of the Psalms are not merely random collections, but together constitute a coherent textual movement and an ordered whole.

❧ Although I had skimmed it before, I finally got around to reading Eric Nelson’s brilliant The Hebrew Republic: Jewish Sources and the Transformation of European Political Thought. Nelson explores the impact of the Hebrew Scriptures upon Western political thought in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, especially as Christian thinkers engaged with them in ways influenced by Jewish interpreters. He argues that crucial shifts in thought at the dawn of modernity occurred in large measure through the leavening of Western political reflection by Jewish biblical reflection.

Nelson focuses upon three principal shifts. The first was the sudden emergence of the stance that republican government was not merely one legitimate (even when preferred) form of government among many (the mainstream traditional position), but required. This position chiefly arose on account of the influence of certain Jewish interpretations of 1 Samuel 8, Samuel’s speech to the people following their request for a king, and Deuteronomy 17:14-20, the laws of the king. The second was the move away from the traditional republican resistance to redistributive agrarian laws to support for the redistribution of land and/or property on account of Jubilee legislation. The third was support for religious toleration in the righteous republic.

Nelson’s book is eye-opening, revealing an important phase of the history of Western political thought that is generally unrecognized or neglected, suggesting that the reading of Hebrew Scripture was a vanishing mediator for surprising aspects of modern political thought. I highly recommend it and anticipate discussing elements of Nelson’s thesis in some forthcoming conversations.

Happenings and Doings

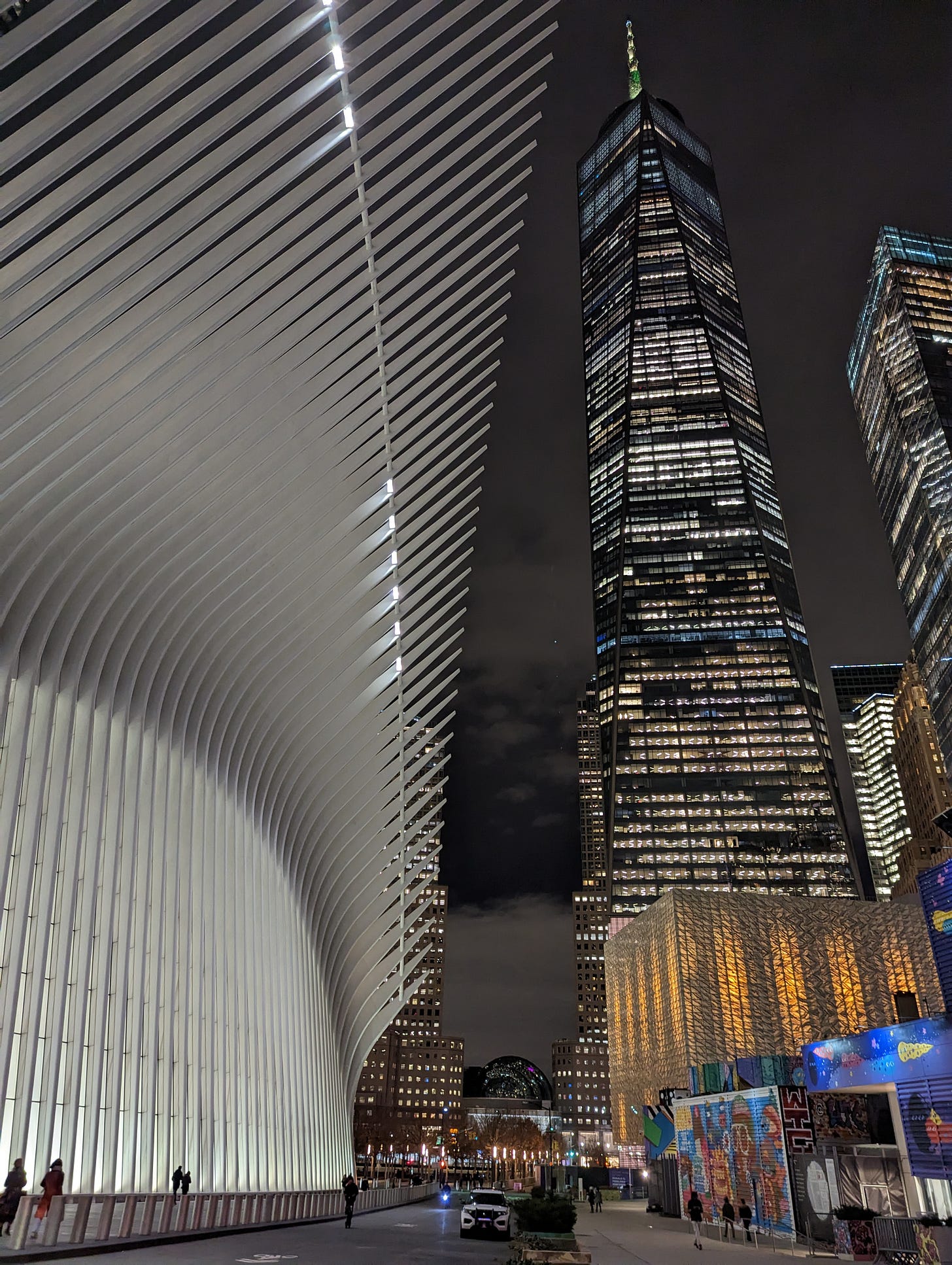

2023 began delightfully, with a small gathering at The Lambs Club for New Year’s Eve. We had feared that the centre of New Year would be impossible to navigate as midnight approached, so we started at 6pm and ended up playing a significant amount of Codenames and For The Queen. We played even more games of Codenames on New Year’s Day, when, after church, we spent a few hours with Susannah’s mum, brother, and sister-in-law.

The start of a new year is always an exciting time, as new possibilities and projects can be envisioned, new habits taken up, and new goals set. On the 2nd, we started our Monday by discussing some of the big things that we wanted to achieve in 2023, producing a daunting yet exhilarating list of intended goals. Alastair knitted another head warmer. We also purchased a bread machine, about which we are exceedingly exited.

Susannah’s mum, dad, and stepmom all came down with COVID over the Christmas period, and later Susannah’s brother, so we were both expecting to get it too. We had planned an Epiphany party, which had to be cancelled after a health scare for Susannah’s dad. Alastair also came down with COVID. Fortunately, he only really had mild cold symptoms so, apart from distancing from people, was still able to get plenty of work done. It might have been very inconvenient otherwise, as he had twenty hours of lectures in Davenant House to plan, a few lengthy articles to write, the first of this semester’s Davenant Hall lessons to teach, a sermon to prepare, three lengthy interviews, several podcasts to record, and much besides.

After around a decade of involvement with the Davenant Institute, Susannah finally got to see Davenant House on Saturday and was instantly charmed. Alastair will be teaching here for the next fortnight and Susannah will be with him for the first week of it. Over the last couple of days we have been catching up with the Littlejohn and the Hughes families and getting to know some of the Davenant students and employees here. The teaching begins this evening.

Yesterday, we had the privilege of joining Christ the King CREC in Greenville for Sunday morning worship. It was an especial blessing to reconnect with several friends and to make a few new ones. The church was incredibly friendly, with lively singing, many young families, and we enjoyed a great meal and time of congregational fellowship and discussion after the service.

Alastair preached on Genesis 11:1-9 and the story of Babel, focusing on, among other things, the contrast between Abraham and the Babel builders. The building of the city and tower of Babel were, in large measure, a response to the threat of death, civilizational and personal. Babel represented a quest for fame and glory, enduring peoplehood, centralized control, resistance to disintegration and the attenuation of power, and security against divine judgment. While the builders of Babel sought to make their name great, in calling Abram the Lord promised to make his name great.

Abraham’s story is bookended by willingness to give up the control that we so often grasp at in the face of the threat of death. In Genesis 12:1, Abraham’s story begins with the call to surrender his past: “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you.” In Genesis 22:2 we find an echo of Abraham’s initial call in another summons: “Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains of which I shall tell you.” Sacrificing Isaac is the surrendering of Abraham’s future. As Abraham does not grasp at life and immortality in the face of the threat of death, but gives himself wholly to the Lord, he becomes an undying blessing, while the Babel builders left only a curse. There are echoes of the Fall to be heard here too.

We spent much of yesterday after church catching up around a campfire and planning stories with the Littlejohn kids. We prayed evening prayer at a local church and then went back to the Littlejohns for food, conversation, and an episode of Yes, Minister.

Upcoming Events

❧ Alastair will be teaching in Davenant House for much of the next two weeks.

❧ Alastair will be attending the Mere Anglicanism conference in Charleston at the end of next week.

❧ Most of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Susannah and Alastair

Excellent update, but I wanted to add that you guys have really upped your photography game. So much better to use your own photos if possible, rather than stock photography .

The Abraham vs Babel contrast hits hard in the middle of current political worries in the church.