№ 2: The Trouble with Chapter and Verse

also Davenant event report, Plough event report, and coffee-related update

Dear friends,

Susannah: I’m writing this from a Joe and the Juice in London, about to head over to the Sekforde pub in Clerkenwell to emcee Plough’s VOWS issue London launch (the NYC launch for this issue was in Central Park just before we left; if you’d like to be on various lists for such events, just reply to this email. I think that should work anyway.)

It’s Alastair’s turn for a long discursive essay this week (it’s almost always Alastair’s turn for a long discursive essay tbh.) He objects to my putting a headline on it because he thinks that’s catering to the very problem he’s describing here, but I am overriding him out of regard for our readers.

The Trouble with Chapter and Verse

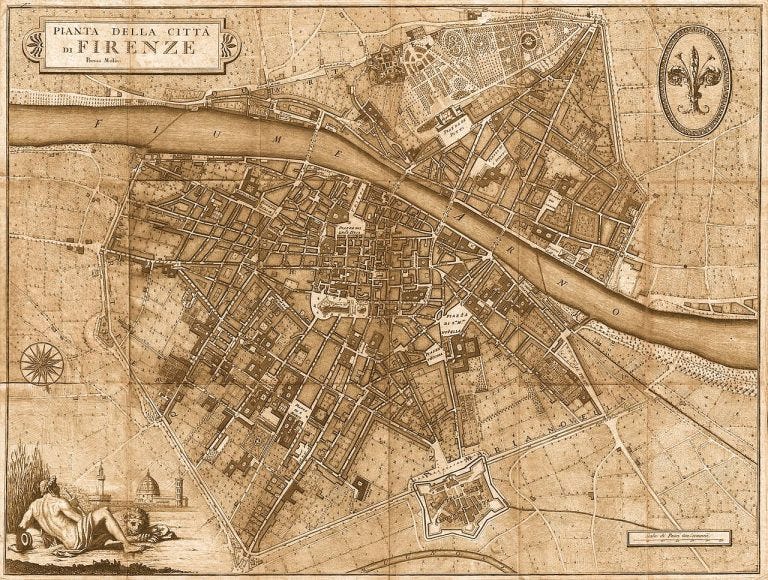

Alastair: In The Practice of Everyday Life, Michel de Certeau contrasts itineraries and maps, which though originally assembled from innumerable itineraries, progressively erased the traces of them they originally bore (residual “narrative” figures such as ships and animals being removed). While an itinerary narrates a path to be performed in a temporal movement by the one following it (‘when you see the butcher’s shop with the blue door, you’ll need to take the next left…’), the map abstracts from such specific passages in time to present the entire terrain to the eye in a single glance and moment.

To find a location on a map, all that is required are the correct coordinates. To find a location through an itinerary, you need properly to ‘perform’ the narrative of the directions, taking the time to follow the path through the terrain to your destination. The user of the map stands outside of a representation of the terrain and can point directly to the location with which they are interested; the follower of the itinerary does not have such immediate access, but must attentively follow directions.

The historic development of the map from prior itineraries is analogous in certain respects with the evolution of other sorts of texts. Even by the thirteenth century, some time before the advent of print, which would accelerate and more firmly entrench the development, books were already evolving from texts designed chiefly for communal oral performance to texts designed more for the private silent reader. As part of this development, texts that were formerly conceived of as more akin to ‘itineraries’ of communal reading designed to form wisdom in a realm of reality through familiarizing performance, started to be regarded as more akin to ‘maps’ of a territory of knowledge.

Books began to be produced with a burgeoning array of navigational apparatus and paratextual tools and the formats of texts also changed (many older texts in the West did not even include spaces between their words). Chapters, verses, page numbers, indices and tables of contents, paragraphs, section headings and divisions, front matter, mises en page, etc. are all examples of things that were developed, elaborated, or otherwise transformed. Such additions allowed for different forms of engagement with—and conception of—texts. Former modes of reading faded, while others rapidly gained prominence.

Such developments encouraged discontinuous, de-temporalized, and spatialized modes of reading. They made it easier to conceive of the text as a mapped-out territory to be mined for information, with the reader able to jump directly from one passage of interest to another, without following any temporal itinerary through the text.

The effect of this shift in modes of reading and the attendant shifts in our conceptions of texts are under-considered by most of us. For instance, the concept of ‘context’ is often used with little consideration of the ways in which contexts typically unfold through time; indeed, the form of this process of unfolding can be integral to how texts mean what they mean. Where texts are conceived of as synchronic containers of mapped-out information, readers can become dulled to the temporal character of their movements. Such modern conceptions of the relationship between the reader and the text are seldom adequately examined in approaches to premodern and biblical texts in the theological academy. Consequently, we are not alert to their subtle yet extensive influence upon our habits of reading and notions of texts.

Our modern Bibles have been thoroughly subjected to such developments, as have our habits of reading them. The chapter divisions in our Bibles were developed by Stephen Langton (c.1150-1228); modern versification only goes back to the sixteenth century, the creation of Robert Estienne. While earlier Jewish texts divided texts into paragraphs and indicated distinctions of sentences and phrases, such divisions marked out liturgical readings and assisted those publicly reading or chanting them in their vocal performance of the texts. Such divisions can be seen in the 54 parshas of the annual Torah cycle. By contrast, modern numbered chapters and verses chiefly serve private readers in discontinuous navigation of the biblical text, allowing us to jump quickly from one location to another. If the parshas function like sequential stages in the pilgrim’s itinerary, chapters and verses might function more like coordinates on the tourist’s map.

The tourist can be like a consumer of places: it matters little how he gets to his destination, provided he does so quickly and with minimal inconvenience. The tourist expects places to be rendered highly accessible and readily consumable, conforming to the manner in which he navigates the world. The journey of the pilgrim, by contrast, involves submission to a process of formation through which he will be enabled to experience its destination appropriately and on its own terms. As the texts of Scripture and historic theological texts are conceived of as more akin to ‘maps’, their readers can become like textual tourists and consumers, increasingly neglectful of the formative textual ‘itineraries’ through which faithful pilgrims are invited into paths of wisdom. Texts are expected to conform to and be rendered accessible to the forms of their inquiries.

Besides Bible design, there are innumerable ways in which the Scriptures and historic theology have been repackaged for contemporary textual tourists and consumers, answering to their demands and expectations. For many, the Bible is treated as a repository of decontextualized motivational or devotional thoughts. For others, it is a reservoir of proof texts for doctrines. Classic theological texts, originally designed to function as formative pedagogies for attentive students, can be redesigned to function more as reference volumes of theological doctrine (Peter Candler has written at length about many of the issues that I am discussing here). However, while those who have not followed the itinerary of the text can locate a particular doctrine in the table of contents or index and jump directly to the point of their interest, without having undergone the intended itinerary they often have little chance of understanding what it is that they find there. They can mouth the right words, but without a real grasp of what they mean. Like the tourist, they may have consumed a location, but they have not really entered, inhabited, or participated in it as the pilgrim can. While the tourist might be able to pinpoint their location on a map, the pilgrim’s knowledge of where she is will be of a completely different kind. So it is with Scripture or classic theology: those who have long been formed in their paths will have a radically different sense of ‘places’ within them (‘places’ positioned in time through memory and anticipation, not merely ‘spatialized’).

Practiced well, liturgy and lectionary can help us reform our encounter with the Scriptures, shaping us to be pilgrims, nor merely tourists, to approach the Scriptures more as itineraries than as a map (reader’s Bibles are a welcome development, while still encouraging a primarily private form of reading). Liturgy and lectionary can submit us to the formative discipline of the scriptural text, under the guidance, direction, and oversight of skilled mentors and experienced practitioners. Likewise, a true theological education requires the learner to undertake a formative pilgrimage into the knowledge of God, under the direction of seasoned guides. The theological ‘tourist’, who casually and haphazardly moves from one doctrine to another, encounters theological truths without attaining any real understanding of them.

The processes of pilgrimage into truth presented by Scripture and theology do not allow for simple shortcuts. They require subjecting ourselves to disciplines and the pursuit of virtues. They demand patience and perseverance. They require skilled guides to lead us and faithful fellow pilgrims to accompany us. The committed pilgrim can take much time to arrive at her destination. And unlike the tourist, the pilgrim who truly arrives at her destination will be a different person from the one who first set out.

Recent Work

Alastair: On the Theopolis Podcast, we recently finished our series on the epistle of James, reflecting on interesting details such as the three and a half years of Elijah’s drought, and the connotations that might have had for the first hearers.

❧ My article on the death of Her Majesty the Queen and a Christian view of sovereignty has been translated into French.

❧ Over the last few months, I have produced a series of episodes with the God’s Story Podcast going through the entirety of the book of the prophet Daniel. This last fortnight we completed the series with chapter 11 and chapter 12. These chapters, the final vision of the book, covers the entire period up to the end of the age. It begins with the conclusion of the Persian empire, then with the rise of Alexander, the Syrian Wars, the Maccabean Revolt, the rise of the Herods, and leads to the coming of the Messiah and the end of the age. If you have ever wondered how to make sense of this dizzying and difficult vision, these episodes might help!

❧ On the latest Mere Fidelity podcast, Michael Niebauer joined Matt Lee Anderson and me to discuss his recent book, Virtuous Persuasion: A Theology of Christian Mission.

❧ The Gospel Coalition just published a reflection of mine on Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement). It was far too speculative for me to get into within such a popular-level piece, but I have often wondered about ways in which Yom Kippur recapitulates and condenses themes from Genesis narratives, as part of a theory that sacrifices and narratives are mutually interpreting. There are a few key narratives of divided pairs of sons in Genesis, a few of which involve further themes that are held in common with Yom Kippur. In particular, consider the stories of Ishmael and Isaac, of Esau and Jacob, and of Joseph and Judah.

In each of these cases, there are a pair of sons with divergent fates, juxtaposed in various ways within the narrative. In Genesis 21 and 22, the sending out of Hagar and Ishmael and Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac are paralleled in several respects. The two juxtaposed narratives have expressions in common—‘so Abraham rose early in the morning’ (21:14; 22:3). They also involve a fateful journey where something is lacking, the near death of the child, the intervention of the angel of God, and the child’s deliverance. We might relate further details such as the ram in the thicket and Ishmael beneath the bush. One of the two lads is sent out into the wilderness, the other lad is almost sacrificed on the holy mountain that would become the site of Solomon’s Temple (Genesis 22:2; 2 Chronicles 3:1). This might make us think of the paired goats of Yom Kippur—one goat sent out into the wilderness by the hand of an appointed party, and the other offered as a sin offering, its blood brought into the Most Holy Place.

Similar connections might be suggested by the story of Jacob and Esau, in which a pair of goats play an important role: serving as a meal presented to the father for approval and blessing and also as part of the substitutionary disguise of Jacob. The goat hair makes Jacob feel like his brother Esau, who is possibly further connected with goats through wordplay upon various similar-sounding terms associated with him (hair, goat, and Seir, for instance). The contrasting pronouncements over the two sons suggest divergent fates: Esau sent out into the wilderness, as it were—‘Behold, away from the fatness of the earth shall your dwelling be, and away from the dew of heaven on high’ (Gen. 27:39 ESV)—while Jacob ascends to the house of God at Bethel in the next chapter.

Finally, in the stories of Joseph and Judah, especially in Genesis 37 and 38, there are various suggestive common details. The supposed blood of Joseph—really the blood of a goat—was presented to Jacob his father. Then, in the next chapter, the unfaithful Judah sends out a different goat—a goat that might here ironically stand for the son that he did not give to Tamar—by the hand of his friend the Adullamite. Besides the two goats (each connected with a particular son) and the divergent fates of a pair of sons, further details might catch our eye in that story:

1. Genesis 38 opens with two unfaithful sons put to death by the Lord himself, much as Leviticus 16 begins by recalling the deaths of Aaron’s two sons Nadab and Abihu.

2. Themes of investiture and divestiture are central in the stories of Joseph and Judah, much as Yom Kippur involves the divestiture and re-investiture of the High Priest.

3. As in the case of Genesis 21 and 22, scholars have long observed the presence of several verbal, thematic, and other parallels between the accounts of Genesis 37 and 38. For instance, both stories involve goats and coats. Likewise, both stories climax with the charge ‘please identify…’ addressed to the father.

4. Traditionally, the pair of goats was divided with a scarlet thread. Genesis 38 concludes with a pair of twins—the heirs of Judah—divided by a scarlet thread. Those twins would go on to have divergent fates. Zerah would be cut off at several key points, such as in Achan and his family, while Perez’s line would lead to David and his dynasty.

What we should make of such possible parallels—if anything at all—requires much further speculation and I will leave it as an exercise for the reader!

Susannah: Two more podcasts from me:

❧ One with my Plough colleague Caitrin Keiper, on the role of vows in Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables; we also discussed Plough’s EiC' Pete Mommsen’s lead editorial, which gives the gist of the issue. Arguably the chief commandment of contemporary life is to keep your options open: what if not doing that, making vows and keeping them, is actually one of the major ways that we become fully ourselves?

❧ And one with John Milbank and a Bruderhof couple. Our conversation with Milbank got into the issues he raised in that Open Letter I mentioned last week. “Christian nationalism” is in the news; why have we given up on Christian internationalism?

The Bruderhof couple are actually the parents of my Plough colleague Maria Hine; Tom and Sue Quinta both came to Christianity after a long sojourn in various other spiritual traditions, including seven years at a yoga-focused commune. They were classic hippies: in the late ‘60s they took a freighter to India, as spiritual seekers; Sue brought, and read on board, the whole of The Lord of the Rings. They ended up in the Bruderhof, but without rejecting what they’d learned on their long strange trip. Their commitment to Christian orthodoxy alongside their respect for the Eastern traditions they learned from is striking.

What We’re Reading

Alastair: I’ve recently finished reading Paul Copan’s forthcoming work, Is God a Vindictive Bully? Reconciling Portrayals of God in the Old and New Testaments, which I read in preparation for a review. I have been revisiting questions of divine violence more broadly in research for the conclusion of my reflections on Joshua, so this was a useful addition to my reading list. I’ve also been reading more around current Christian debates about nationalism. I have just started Terry Eagleton’s Materialism.

Susannah: I took a break from Arrakis but the Golden Age scifi bug had bit and bit hard, so I ended up reading Heinlein’s Methuselah’s Children.

Heinlein is such a case. His primary hero, Lazarus Long, has - through a quirk of genetics and then through advanced technology - basically cracked the ability to live, and live, and keep living, and is the oldest member of the enormous, more-than-a-hundred-thousand person tribe of long-livers called the Howard Families.

They’re all very, very long lived, though they can die. (Also they’re basically all libertarians, and most of the men wear kilts.) And (we see this more clearly in Time Enough for Love, the sequel) this indefinite prolongation of life is not all it’s cracked up to be. This is immortality not as an entrance into new life but as in prolongation of life - and the books show, pretty bleakly, what that would look like. Lazarus is bored, bored to the point of suicide: with all the time in the world, nothing matters.

Lazarus has a tremendous zest for life; he’s a bit of a scoundrel and a political libertarian and loves adventure and sex and drama - but his wealth of time, time without eternity, gives him the character of someone who, disastrously, never has to work for a living: a wastrel. And he seems to take on this character almost despite his author’s desire: Heinlein is good enough that he can’t quite manage not to be accurate in his psychology and characterization, even though this makes his hero into someone who is bleeding that quality that Heinlein most admires: gusto, lust for life, will.

With all the time in the world, Lazarus becomes something like someone who has all the money in the world: he becomes a dilettante. And this is something Heinlein hates: the second planet that the Howard Families visit in Methuselah is a kind of country of the lotos-eaters; it’s no place for Good American Stock, as Heinlein would put it (everyone in this world is not just a kilt-wearer and a libertarian but a little bit racist) because it’s not challenging enough.

But with all the time in the world, nothing is challenging enough.

Nothing matters.

Specifically what does not matter are those relationships which participate most keenly in what you might call the drama of time: a marriage, where you promise fidelity till death; there are no permanent marriages among the long-livers of the Howard Families.

One’s children, one’s parents: there are no strong filial ties among the Howard Families, because, basically, everybody has too many children, and because you will live essentially forever, there is no sense of generational passing: none of that sweet melancholy, which turns out to be the same as the joy of parenthood.

It’s an interesting contrast with the Christian idea of immortality, which involves both a change in the nature of you, and a change in the nature of time. Christian immortality is not just one damn thing after another: it is a new kind of life, a new entrance into life itself. Till now, you had been only half-alive, had known only an echo of what life really is.

And time, in the New Heavens and New Earth of Christian eschatology, takes on the character of that which isn’t time: eternity. We don’t know what this will be like, but it’s interesting that Adam and Eve are barred from eating of the Tree of Life. Lewis somewhere speculates that this was a mercy to them: if they had, they would be robbed of the need to make the commitments that lead to immortality, through being given mere prolongation: if you keep putting off death, you can keep putting off repentance, until you have become so hardened in yourself that you no longer can repent.

Once again: so enjoyable. But these books are making me deeply grateful not to live in the world that they describe.

Happenings and Doings

Two Saturdays ago, we were down in London for the second annual Davenant UK convivium. Titled In Service of Scripture: Rediscovering Reason and Tradition in Evangelical Theology, the day-long event featured Dr. David Shaw as its keynote speaker.

As this goes out, Susannah is still down in London, having launched Plough’s VOWS issue at the Sekforde pub in Clerkenwell; John Milbank, King-Ho Leung and Elizabeth Oldfield were speakers.

The pub had two event spaces: the other one was apparently being used by a militant Communist student gathering. Accidentally, three of the students made their way to the Plough event rather than the Communist event, and stayed, somewhat confused, but interested. They asked questions in the Q&A, and afterwards, Joy Clarkson, the Books & Culture editor of Plough, mentioned to them that actually, the community that publishes the magazine doesn’t have any private property, holding all things in common.

“Why?” they asked.

“Because they think Jesus wants them to,” Joy explained. It was a very weird but extremely fun cultural crossover.

Closer to home, Susannah’s daily routine has been utterly transformed by the opening of a new Starbucks just down the road from us. Momentous news for the Roberts household! Susannah is happy about this every day.

Alastair’s dad turned seventy on Tuesday. We joined his parents for a very special meal in celebration. A larger family celebration is scheduled for next weekend. Susannah baked Phil some iced cinnamon rolls, which she considers to be a success. Go here for the recipe. A good tweak is adding a ton more spices to the brown sugar mixture - cloves, nutmeg, ginger, etc.

Last Sunday, we went back to one of our regular haunts, Trentham Gardens. Trentham is an old manor house about 7 minutes’ drive away from us, the grounds of which were designed by Capability Brown beginning in 1758. It’s grand and beautiful but there’s also something children’s-book about it; this is a landscape that you expect psammeads from.

We didn’t run into any, but we did run into a couple of grey swans, under new ownership since the death of the Queen (all swans in Great Britain are the property of the monarch.) These ones were quite inquisitive. Wait for it.

Upcoming Events:

We plan to attend this walk in the Shrewsbury area on the 22nd. If you are in the region, we would love to see you there!

Until next time,

Alastair and Susannah

Alastair, this was a wonderful piece, thank you. Like many, seminary triggered a crisis of faith in my life, and it was in my discovering our heritage in the church fathers and mothers, and the ACNA tradition, that helped me not lose faith in Jesus and the truthfulness of our scriptures. I will say it's funny how much more I enjoy reading the Bible after purchasing the ESV Reader set (not to mention how much more fruitful it has become). Not worrying about the chapter and verse markings makes a huge difference.

Naomi Baron (among many others, I'm sure) has discussed the navigational aspect of reading and its impact on memory and integration:

>> The discrepancies between print and digital results are partly related to paper’s physical properties. With paper, there is a literal laying on of hands, along with the visual geography of distinct pages. People often link their memory of what they’ve read to how far into the book it was or where it was on the page.

>> But equally important is mental perspective, and what reading researchers call a “shallowing hypothesis.” According to this theory, people approach digital texts with a mindset suited to casual social media, and devote less mental effort than when they are reading print.

(from https://bigthink.com/neuropsych/reading-memory/)