№ 5: The Cosmos in a Tent

The Tabernacle as the seed of a new creation. Also, Whit Stillman, Cicero, and Ethnonationalism.

Dear friends,

This is our fifth Substack! After nearly a fortnight apart from each other, we are back in New York together and getting geared up for Christmas.

This has, for Susannah, involved prepping cookies to bake and making large numbers of Froebel stars, instructions for which are here.

What’s the Point of the Tabernacle?

After the drama of Moses childhood, the theophanic encounter at the burning bush, the Plagues, the Passover, the crossing of the Red Sea, the miraculous provision of manna and water on the journey to Sinai, and the gift of the Law, the rest of the book of Exodus is largely taken up with assorted case laws, instructions for building a rather unexceptional tent sanctuary and its furniture, and lengthy descriptions of their subsequent construction. Listening through the book, we might wonder how the thrilling narrative of its first half could lead to such an underwhelming denouement.

How can the tabernacle be seen as a climactic realization of the purpose of the deliverance of Israel from Egypt? The text does not offer us an easy answer to this question, but, for those who are prepared to attend to it more closely, it provides some crucial hints. Reflecting more deeply upon it, we may even discover some illuminating truths.

When attending to the Scriptures, we should be especially alert to the ways in which texts can allude to other texts. Such allusions often provide us with clues to the meaning of events, persons, or other entities. In the second half of the book of Exodus, we find a great many allusions back to the book of Genesis, allusions which together suggest that the author of Exodus regarded the construction of the tabernacle as an event of cosmic import.

Early in the book of Genesis, a group of people were delivered from a catastrophic judgment that fell upon a sinful society. They were brought to a mountain, where God made a covenant with them. This group were the seed of a new society, which would go on to transform the world. Noah’s Ark was the seed of the postdiluvian creation.

Besides such broad analogies in storyline, in the account of the Exodus, there are several allusions back to or details that are reminiscent of the story of the Flood. And here the contrasts are as noteworthy as the similarities.

As Rabbi David Fohrman has observed, both accounts involve the creation of a wooden box, with divinely given measurements (Genesis 6:13-21; Exodus 25:10-16). Noah’s Ark is a large wooden box, overlain inside and out with inglorious pitch; the Ark of the Covenant is a much smaller wooden box, overlain inside and out with glorious gold. The first wooden box contains the remnant of humanity in a world returned to formlessness, whereas the second is the object that, as the footstool of the Lord’s earthly throne, symbolizes his holy and majestic presence amid his people in a world overwhelmed by sin.

The story of Noah is structured as an extended chiasm, with the Lord’s remembering Noah at its heart. Within the literary chiasm, there is a numerical chiasm of days to be observed: 7, 7, 40, 150, 150, 40, 7, 7. In Exodus 24:15-18, there is once again a period of seven days, followed by a period of forty days.

Noah’s Ark was a three-storey covered structure, its three storeys perhaps recalling the three-storeyed character of the creation—the sea and the realm below the earth, the earth, and the heavens—and the ascending levels of the tabernacle—the courtyard, the Holy Place, the Most Holy Place. The dimensions of Noah’s Ark have several points of resemblance with those of the tabernacle and its furniture. Noah’s Ark (300 x 50 cubits) was the exact size of three tabernacle courtyards (100 x 50 cubits) laid end to end. The breadth (50 cubits) to the height (30 cubits) of Noah’s Ark had the same ratio (5:3) as the length (2.5 cubits) to the height (1.5 cubits) of the Ark of the Covenant. Presuming Noah’s Ark’s three storeys were of equal height, they were each ten cubits high, the same height as the tabernacle. Each of these storeys (300 x 50 x 10 cubits) would have been able to contain the tabernacle proper (30 x 10 x 10 cubits) exactly fifty times over.

In Exodus 32-34, there are events that might recall the story of Noah. After the Israelites’ sin with the golden calf, the Lord tells Moses that (like Noah) he is minded to destroy the people and start anew with Moses alone. In apparent contrast to Noah, though, Moses intercedes for the people and they are saved.

In Exodus 40:16-19, we read of Moses’ erection of the tabernacle:

This Moses did; according to all that the LORD commanded him, so he did. In the first month in the second year, on the first day of the month, the tabernacle was erected. Moses erected the tabernacle. He laid its bases, and set up its frames, and put in its poles, and raised up its pillars. And he spread the tent over the tabernacle and put the covering of the tent over it, as the LORD had commanded Moses.

The significance of Moses’ erection of the covering on the tent on the first day of the second year should recall Genesis 8:13—

In the six hundred and first year, in the first month, the first day of the month, the waters were dried from off the earth. And Noah removed the covering of the ark and looked, and behold, the face of the ground was dry.

As in the story of the Exodus, the New Year following a year of judgment and deliverance opened with a significant act: in Genesis the covering of the Ark was removed, whereas in Exodus the covering was placed over the Tabernacle.

In such points of similarity and contrast, the text of Exodus invites its hearers to hear it in conversation with the story of the Flood in Genesis. If the Flood preserved a seed of human and animal life to grow in the postdiluvian world, the Exodus is another deliverance that concludes with the planting of a seed of divine presence in a world of sin.

Heard in such a manner, the second half of Exodus arguably eclipses the first in the scope of its apparent concern. Whereas the first half focuses upon the deliverance of a particular people from cruel bondage, in the second half we begin to see the cosmic scope of the intent of this deliverance.

Commentators often observe the allusions back to the creation account of Genesis 1 and 2 in the descriptions of Moses’ work in establishing the tabernacle in Exodus 39 and 40. God finished his work and blessed and consecrated the Sabbath day and Moses finished the work of the tabernacle and blessed the people and consecrated the tent (Exodus 39:43, 40:9-10, 33-34). We might think of the tabernacle itself as comparable to the Sabbath day in some respects: if the Sabbath is the day where God rests from his labours, the tabernacle is the place where God will rest among his people.

This picture can be developed further through consideration of the design of the tabernacle given in Exodus 25-31. In Genesis 1 and 2, there is a pattern to the days of creation. The first three days are days of forming and division: day and night, heaven and earth, sea and earth. The second three days are days of filling and delegation, corresponding to the first three. On Day 4, the light of Day 1 is filled out and its task ‘delegated’ to the governing lights of the Sun, Moon, and stars. On Day 5, the firmament above and the waters below, divided on Day 2, are populated by birds and fish. On Day 6, the land of Day 3 is populated by land animals and its rule delegated to Man. In Exodus 25-29 we see two recurring phrases, which correspond to forming (25:9, 40; 26:30; 27:8) and filling/delegating phases (27:21; 28:43; 29:9) in the tabernacle’s construction. The first phrase concerns the pattern given on the mountain, according to which all must be formed; the second phrase concerns the enduring character of the Lord’s statute throughout the generations of Israel.

Attending to the instructions for building the tabernacle, I believe that we can perceive the seven-day pattern of creation in two successive cycles: the first in chapters 25-29 and the second in chapters 30-31.

First Cycle (Exodus 25-29)

Day 0: Creation formless, void, and dark—materials gathered for the building of the tabernacle (25:1-9)

Day 1: Light formed—Golden items created: Ark of the Covenant, mercy seat, table of shewbread, golden lampstand (25:10-40)

Day 2: Firmament dividing heaven and earth—Tabernacle structure, its screens and its veils (26)

Day 3: Earth and Seas divided—Tabernacle courtyard and the bronze altar within it (27:1-19)

Day 4: Lights placed in the heavens to rule the day and the night—Oil for the lamp (27:20-21)

Day 5: Creatures made for the firmament above and waters below, divisions established on the second day—Priests’ garments conforming them to the symbolic ‘heaven’ of the tabernacle (28).

Day 6: Animals and man created—Consecration of Aaron and his sons for tabernacle service (29:1-34).

Day 7: Completion of the work and consecration of the Sabbath—Completion of the seven day ordination and consecration of the tabernacle ceremonies and initiation of the ordinary daily sacrificial cycle (29:35-46).

Second Cycle (Exodus 30-31)

Day 1: Golden altar of incense, corresponding to the glorious golden items of the first cycle (30:1-10).

Day 2: Silver census tax, which was used to ‘cover’ the people and to construct the tabernacle structure, connecting the people with the tabernacle (30:11-16; cf. 38:25-31).

Day 3: Bronze basin (note the gold-silver-bronze movement from days 1-3), placed in the courtyard with the bronze altar (30:17-21). The altar corresponds to the land and the basin to the sea.

Day 4: Anointing oil for the furniture and utensils and the priests (30:22-33), corresponding with the oil for the lamp.

Day 5: Incense, the clouds in the firmament of the tabernacle (30:34-38).

Day 6: Appointment of Bezalel and Oholiab as chief craftsmen, and filling of Bezalel with the Spirit (31:1-11).

Day 7: The covenant sign of the Sabbath (31:12-18).

If the tabernacle is the divine seed of a new world, with God’s presence at its heart, one can read the rest of the Pentateuch—and, indeed, the rest of the Bible—in terms of this. Leviticus largely concerns the service within the tabernacle, the pattern from which Israel’s life would be ordered and the reality according to which everything would be regulated. In Numbers, the scope widens. It begins by ordering the entire camp of Israel around the tabernacle at its heart. In Deuteronomy, Israel is prepared to be planted in the Promised Land.

A recurring motif elsewhere in the Scripture is that of water flowing out from the Temple into the wider world, bringing life and renewal. This harkens back to Genesis 2, where rivers flowed out from the garden sanctuary of Eden to give life to the world. Humanity, the text implies, would need in time to venture out from the garden, bringing the order and life of the verdant garden into a world that was yet uncultivated, while bringing the treasures of and the fruits of human labour in the wider world back into the garden. The garden was thus the model for, the source of, and the chief gathering place of man’s transforming task in the whole creation.

Recognizing the garden as the proto-sanctuary equips us to perceive the analogies between it and the tabernacle. Yet, within the symbolic world of Scripture, analogies are multiple, and draw our attention in many different directions. The tabernacle is analogous to Eden, to Israel, but also analogous to the entire creation. Perhaps especially significantly, the tabernacle is analogous to the human person. The Most Holy Place is the inner heart, wherein God must be enthroned, and his Law treasured. The lampstand is like the eyes and the understanding. The table corresponds to the mouth and the stomach, by which things are assimilated into the body. The table of incense corresponds with the sense of smell and with breath. The tabernacle structure is like the human skeleton and the skin that covers it. The water, as becomes clearer in the Temple and later prophecy, can represent the generative fluids of the body.

The operations of the tabernacle, then, present us with a model of a person who orders his life around God’s presence and whose interface with the world—in sight, smell, taste, and touch—is regulated by an inner attention to and meditation upon the Law of God.

In concluding with the revelation of the plans of the tabernacle and its construction, Exodus presents the deliverance from Egypt as climaxing in the gift of a divine pattern for human existence, filled with God’s own empowering presence, pregnant with the promise of the world set free from its greater bondage to sin, God’s will being done on earth as it is in heaven, as men and women live together in communities of justice and fruitful peace.

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ An Advent-themed piece of mine has been published in the recent Generations issue of Plough. Within it, I discuss the genealogy with which Matthew’s gospel—and the New Testament more generally—opens:

A genealogy such as Matthew’s is a way of alluding to and evoking a larger narrative, not unlike the “previously on…” recap before the first episode of a new season of a television series. It situates new events within the arc of a larger narrative, of which they will serve as the culmination. The gospel narrative does not begin in a historical vacuum, but as the climax of a long history of God’s dealings with Abraham and his descendants. Matthew’s catalog recalls familiar names that represent some of the narrative’s most important moments, recollecting earlier events and characters so that the hearer recaptures the threads of the greater story. This, of course, is one of its most important purposes: any who might otherwise be tempted to regard the New Testament as entirely self-contained are immediately charged to understand Matthew’s account against the vast backdrop of the Old Testament.

My friend and Theopolis colleague James Bejon has also recently been ruminating on questions that have bearing on Matthew’s genealogy. Besides their relevance to Matthew’s genealogy, Bejon’s observations about the number 42 might also have connections with some thinking I was doing lately about some interesting numbers in the book of Numbers. In Numbers 33, there are 42 stations in Israel’s wilderness itinerary. In Numbers 31, much attention is given to the division of the vast spoil, which sums up to 840,000 items, halved between the 12,000 warriors (840,000 = 12,000 x 70) and the congregation (420,000 items for each group). Bejon and I are working on a course—and a book—on the subject of biblical numerology together, so we will be getting much deeper into these questions.

❧ Shane Morris interviewed me on the subject of biblical typology in Advent and Christmas stories for the Colson Center’s Upstream podcast. You can listen to our discussion here.

❧ Our most recent Mere Fidelity episode is on the subject of gratitude, with Dr Kent Dunnington as our guest. Within it, we discuss the way that the typical logic of gift is subverted in the life of the people of God. In the Church, the Gift of the Holy Spirit is the gift of our very selves in Christ—and God’s gift of himself—membered in manifold spiritual gifts. Counterintuitively, we become more fully partakers in the communion of the Spirit as we give freely to others. The economy of gift that the gift of God in Christ establishes transforms the dynamics of scarcity and debt that so often govern human gift relations. The practice of thanksgiving is a redounding of the divine gift in escalating cycles of gratitude.

❧ On the Theopolis Podcast we continue our series on James Jordan’s Through New Eyes (the influence of which is ubiquitous in my thinking and writing). Since our last Substack, our discussions of chapter 3 (‘Symbolism and Worldview’), chapter 4 (‘The World as God’s House’), chapter 5 (‘Sun, Moon, and Stars’), and chapter 6 (‘Rocks, Gold, and Gems’) have all been released.

❧ A couple of weeks ago, in the course of a Twitter discussion about Stephen Wolfe’s newly-published book The Case for Christian Nationalism, I set in motion an online controversy through my disclosure of Thomas Achord’s pseudonymous Twitter account and publications. Achord was the co-author with Darrell Dow of Who is My Neighbor? An Anthology in Natural Relations. He also co-hosted the Ars Politica podcast with Stephen Wolfe.

The timing of my initial revelation, just before Thanksgiving, was very unfortunate. While there is no ideal timing for such significant revelations, I quite regret, for all parties involved, unintentionally having so disrupted the holiday weekend. In the UK, the fourth Thursday in November is just another workday, leaving me unmindful of the impact that this would have. I apologize to everyone that this affected.

Responses have varied. By far, most people understood and supported the need to bring these things to light. Some, though, criticized me for, in their view, not addressing Achord as though he were in private sin; that is, not observing the instructions of Matthew 18. My approach to these broader controversies has neither been precipitous nor escalatory. On the appropriateness of addressing published positions in public, in the manner that I did, Jonathan Tomes ably handles the objections in this article.

When a rising voice in a growing ‘Christian nationalist’ movement is publishing racist and hateful material under a light alias (one known to many of his near associates), while being the closest collaborator with the current leading voice of the movement, whose theories he is both championing and using for his own racist ends, it seems reasonable to me that these facts should have bearing upon how we regard this iteration of the Christian nationalist movement.

I’ve decided against publicly responding to the various counter-allegations that have been made against me, as I have been convinced that their baseless and unconsidered character will be amply evident to any person investigating them in good faith. If anyone has questions, I would be delighted to answer them privately.

Achord has now confessed his guilt and is committed to repentance under pastoral guidance. As Susannah and I have done throughout, we will be praying for our brother’s full restoration in the joy, love, and forgiveness that is ours in Christ, and for the good of him, his family, and their community. Please join us in actively seeking this.

Susannah:

❧ The Generations issue of Plough is off to the printer - you all should be getting your Winter issue in the mail shortly. Go here to subscribe if you’d like to! I think (obviously I am unbiased) that it’s one of the most physically beautiful magazines being printed these days.

This has been a really fun one to work on. Highlights for me among those pieces already up on the website:

❧ Prinz Michael zu Salm-Salm’s “10 Theses on Intergenerational Stewardship.” When your family has stayed on the same land for a thousand years, you learn something about how to care for the natural and social worlds that you’ve inherited.

❧ Peter Mommsen’s lead editorial, “Yearning for Roots,” discusses why we decided to do this issue in the first place - and gets into the vexed issues surrounding the goodness of having roots and the legitimacy of our desire for them, while at the same time upholding the relativizing of family loyalty as compared with our loyalty to the Kingdom of God. It is good for us to have a place and a people - but we can’t fall into the worship of blood and soil. In this issue as in so many others, what we need to aim for is ordered and concrete love.

In my view, the excesses of blood and soil nationalism become tempting when you don’t have a concrete actual family, a kin group, to love, and when you don’t have a solid actual church community, in which we often experience kinship in Christ across difference of background, class, and ethnicity. When that happens, your own ethnicity can take an inflated position in your heart. Basically my prescription is: have a lot of cousins and friends and you won’t have the leftover emotional energy to be an ethnonationalist in any way that is actually destructive of our political community because you will be too busy loving your actual kith and kin. (This is not a complete prescription but I think it helps.)

❧ My “Forerunners” column for the issue was on Monica of Thagaste, St. Augustine’s mother. I had a lot of fun with this piece, and came to like Monica a good deal more by the end than I had at the beginning of researching her. (Tl;dr: she was too much of a snob to let her son marry his commonlaw wife, despite the fact that they’d been together for thirteen years, which was really horrible of her; but she did turn out to be a very good grandmother to Augustine’s son, and I love her and Augustine’s intellectual partnership - they started talking about philosophy and theology when he was a kid, and did not stop the conversation until she died, even though they spent years in fundamental disagreement.

Also it was a beautiful thing to see the existence of the slightly overbearing Upper East Side society mom as an eternal human type, manifesting in Monica’s case in late classical North Africa. She would totally have owned several pomeranians had such creatures existed in Hippo in AD 375. And shopped at Balducci’s.

I had to cut the following chunk of the bio for space reasons, but I’m giving it to you here:

We know Monica almost entirely through the eyes of her son: her story is interwoven throughout his Confessions. She comes through as herself - the faithful, loving, stubborn, somewhat prideful Christian North African/Roman matriarch.

She also is cast as many others; she partakes in their natures too - and who’s to say that Augustine was wrong in so casting her?

She was the Widow of Nain, seeking from Jesus the life of her dead son. She was Dido, from whom Aeneas fled from Carthage to Rome. Perhaps above all, she was the Persistent Widow of Jesus’ parable about the value of doggedness in prayer: the one of whom the unjust judge said, “Though I neither fear God nor have regard for people, yet because this widow keeps on bothering me, I will give her justice, or in the end she will wear me out by her unending pleas.’”

But we have one other testimony to her.

In the summer of 1945, two boys were digging a hole to plant a post for a soccer goal in the courtyard outside the church in Santa Aurea in Ostia. Their shovel hit a stone. On that stone was an inscription. It was Monica’s funerary marker, with her epitaph.

Her body had been long since moved to the city of Rome proper, to the Basilica dedicated to her son. The text had been known because it had been recorded at the time of its composition and inscription. But the stone itself had been lost. A translation of the Latin reads:

Here the most virtuous mother of a young man set her ashes, a second light to your merits, Augustine. As a priest, serving the heavenly laws of peace, you teach the people entrusted to you with your character. A glory greater than the praise of your accomplishments crowns you both – Mother of the Virtues, more fortunate because of her offspring.

It just amazes and delights me when the past does not stay buried like this: when Providence reminds us that we are not cut off from our own history, that there is, always, more to be discovered.

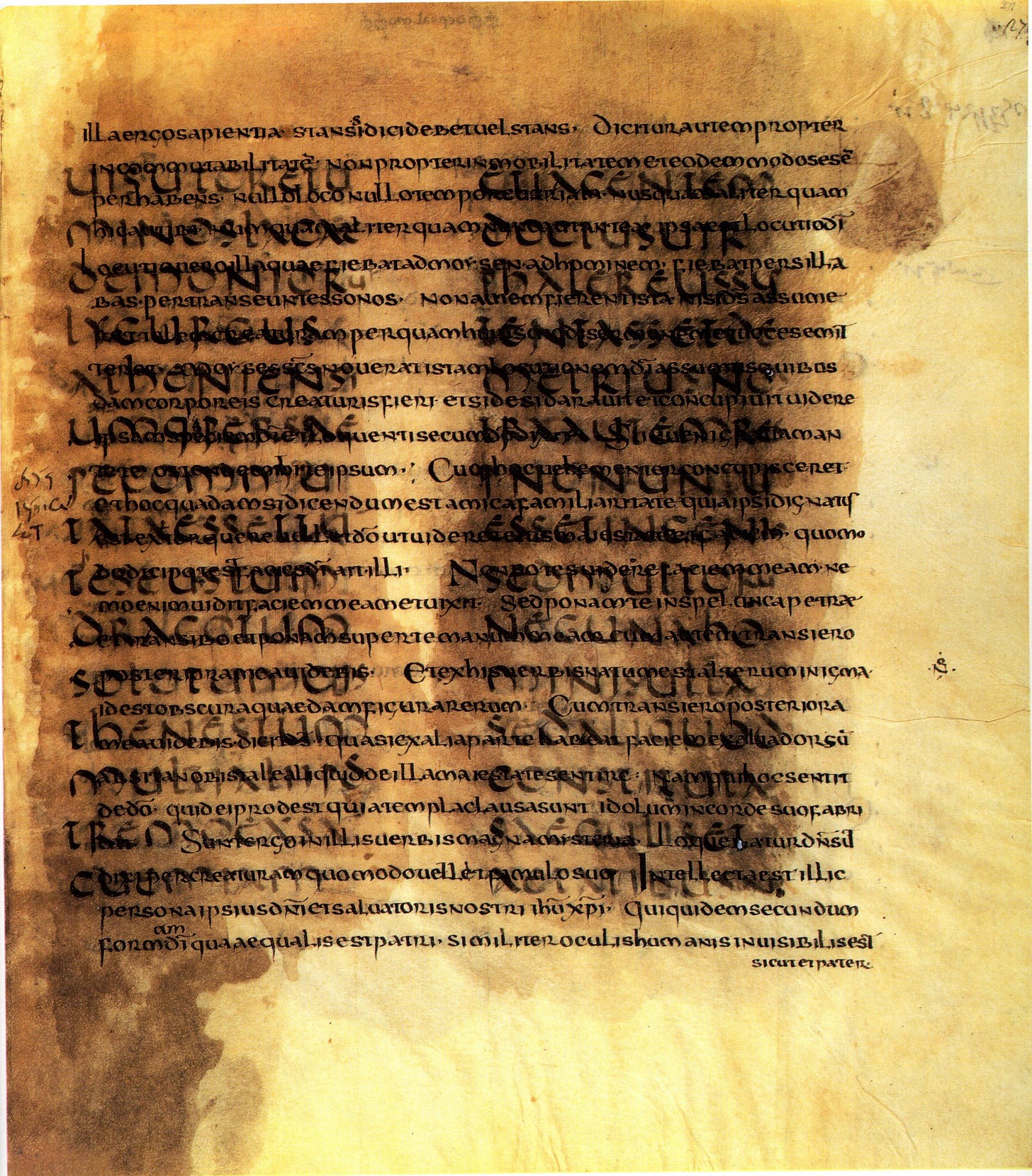

❧ Another example of such an unburying is the retrieval of Cicero’s lost book De re publica, his takeoff on Plato’s Republic, which for more than a thousand years we knew about because other authors had referred to it, but of which we had no surviving copy. In 1819, several years after Napoleon had been evicted from Rome with extreme prejudice, and several years before anyone really took seriously the idea of establishing a nation of Italy and making Italians out of the people who lived there, Cardinal Angelo Mai, a Jesuit from Lombardy living in Rome found something odd in the Vatican library - a codex copy of Augustine’s Commentaries on the Psalms, which had been made using old kidskin - the leaves of the book had had the original ink scraped off and had been reused to make a copy of the Augustine. This was a common practice, because kidskin was so expensive. The resulting double text is called a palimpsest, and sometimes, it is possible to read the older text, as the ink never does get fully removed.

Cardinal Mai, reading the ghost text beneath the Augustine, realized what he had found: the first semi-complete copy of Cicero’s De re publica that anyone had seen for a thousand years.

Cicero had written the Re publica, he said, “when he held the rudder of the state” - that is, when he had returned from exile to active political life. It and the Laws are, unlike Plato’s Republic and unlike anything that Aristotle or St. Thomas wrote, political philosophy written by an active statesman, rather than a theorist. That fact points up something crucial about political philosophy - something that is I think often lost.

What kind of thing is political philosophy? What genre is it? I think it can be best understood as a species of wisdom literature: culled from across time and place, from men, and the occasional woman, working in many different kinds of polities, with many different visions for how those polities should be shaped: from cheek-by-jowl Greek and German city-states to expansive regions containing a dozen or a hundred manses and villas with their home farms, producing most of what they need within the estate; from placid monoethnic statelets to kingdoms made up of two or three just-stopped-warring peoples; from polyglot imperial cities to the empires themselves - and to multiethnic federated republican commonwealths like our own.

Political philosophy explicitly describes itself this way: the art of politics, the art of the statesman, is a matter of phronesis, practical wisdom: understanding one’s times, one’s people, one’s state, to be able to apply the right truth at the right time.

The most obvious Christian example of a piece of wisdom literature is, of course, the book of Proverbs. It, like the classical tradition itself, presents the reader with a quest, and it is, strangely, the same quest: a romantic search, driven by an almost erotic love, for what it calls Wisdom, personified as a hospitable, good, and wise woman – the wife most to be desired. The young prince – the future statesman – must become an espoused lover of Wisdom; in Greek, a φιλόσοφος: a philosophos, a philosopher, prepared to take wise action in his own life and in the life of his polity.

Proverbs is of the specific genre of philosophy called a speculum principis, a Mirror for Princes. We receive it and are called to the task because we are, as sons and daughters of Israel in Christ, all princes, and this quest has become ours.

It was certainly something like what Cicero understood his task to be. The commonwealth that he was seeking to build was one that he understood as a law-and-citizenship based rather than tribe or clan-based polity. It was, in the technical sense, a cosmopolitan project: Cicero, not a native Roman, saw Rome as an ikon of the Cosmopolis, the Stoic version of Augustine’s City of God.

Something, indeed, like the tabernacle itself: it was a cosmos in miniature. It was an appropriate ikon because it was made up of citizens of many different gens, many different nations and ethnicities: to navigate the promise of such a multiethnic republican commonwealth was, precisely, Cicero’s project as a statesman.

Which was why I got so ticked off when, reading Stephen Wolfe’s The Case for Christian Nationalism, I found him attempting to use Cicero - of all people! - to argue for the need for a monoethnic polity. My review of Wolfe’s book appeared the day before the drama about Wolfe’s explicitly white nationalist collaborator exploded. In it, I examine the mystery of bad reading: how he could have come to use Cicero as a source to argue for something that was the opposite of Cicero’s own project.

❧ I’m pretty proud of the Wolfe review. I’m also EXTREMELY proud of the alt lyrics that I came up with yesterday after my friend Dan Walden pointed out that the whole Sam Bankman-Fried situation was beginning to look increasingly like the part of Guys and Dolls where Nathan Detroit has to figure out a place to have the crap game but he doesn’t have enough money to cover the overhead for the bribe of the garage owner:

The Coinbase execs have a brand

But we ain’t got the cash in hand

And now they’ve encrypted for sure

The old Bored Ape coders’ backdoor

There’s that ledger that’s based in Qatar

But Mrs Nazarov ain’t a good scout

And things being how they are

The FTC’s servers are out

So the Coinbase platform is the spot

But the three billion bucks we ain’t got.

Happenings and Doings

Alastair: Since our last Substack, we spent a delightful Saturday in Shrewsbury with several others, being shown around by our friend Tim Vasby-Burnie. Susannah had to leave early, but I stayed on for a few more hours and got to visit one of the best books and collectibles stores I’ve ever seen.

The next Sunday, after Susannah had returned to the US, I walked along the canal for a couple of hours.

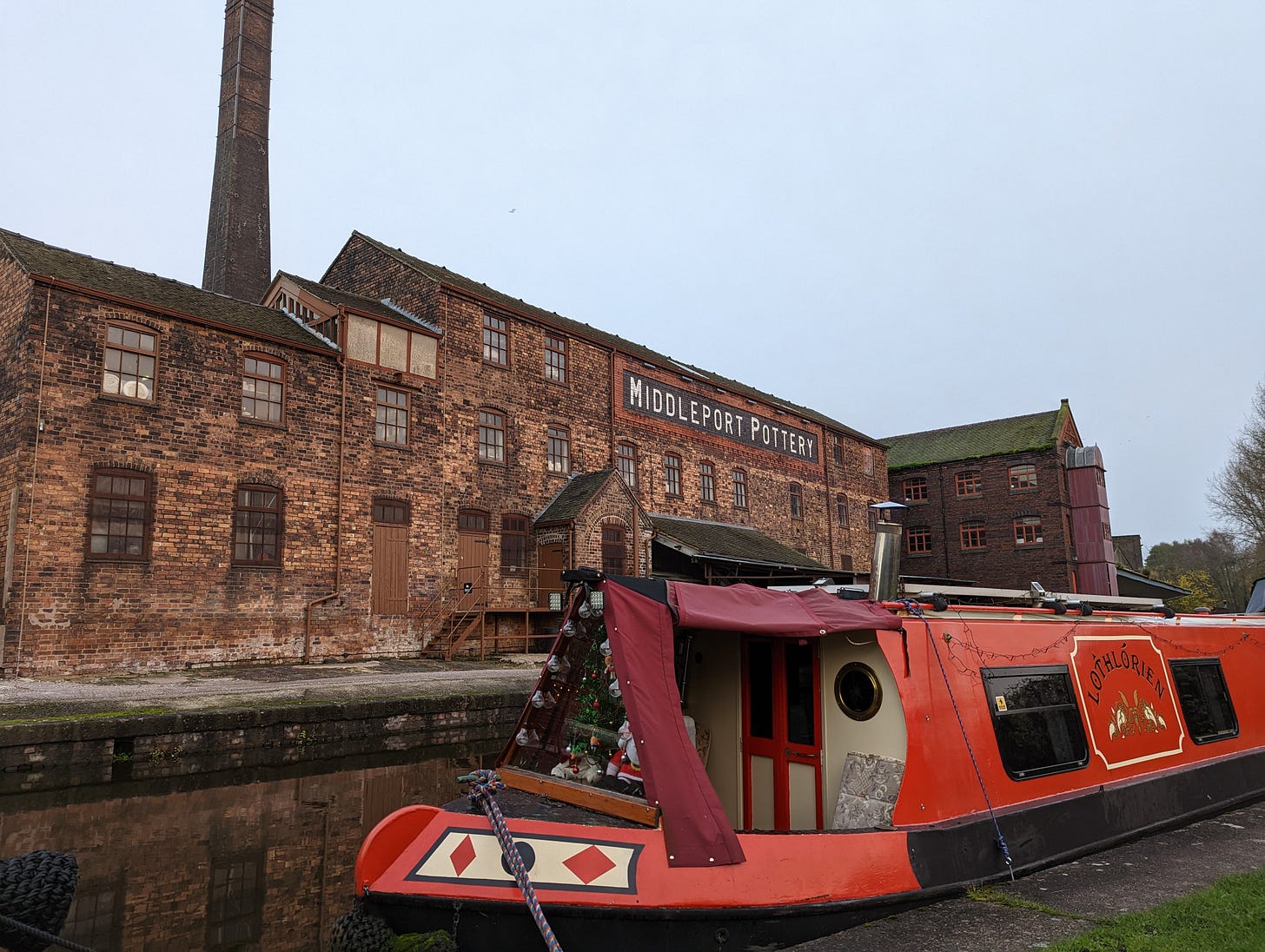

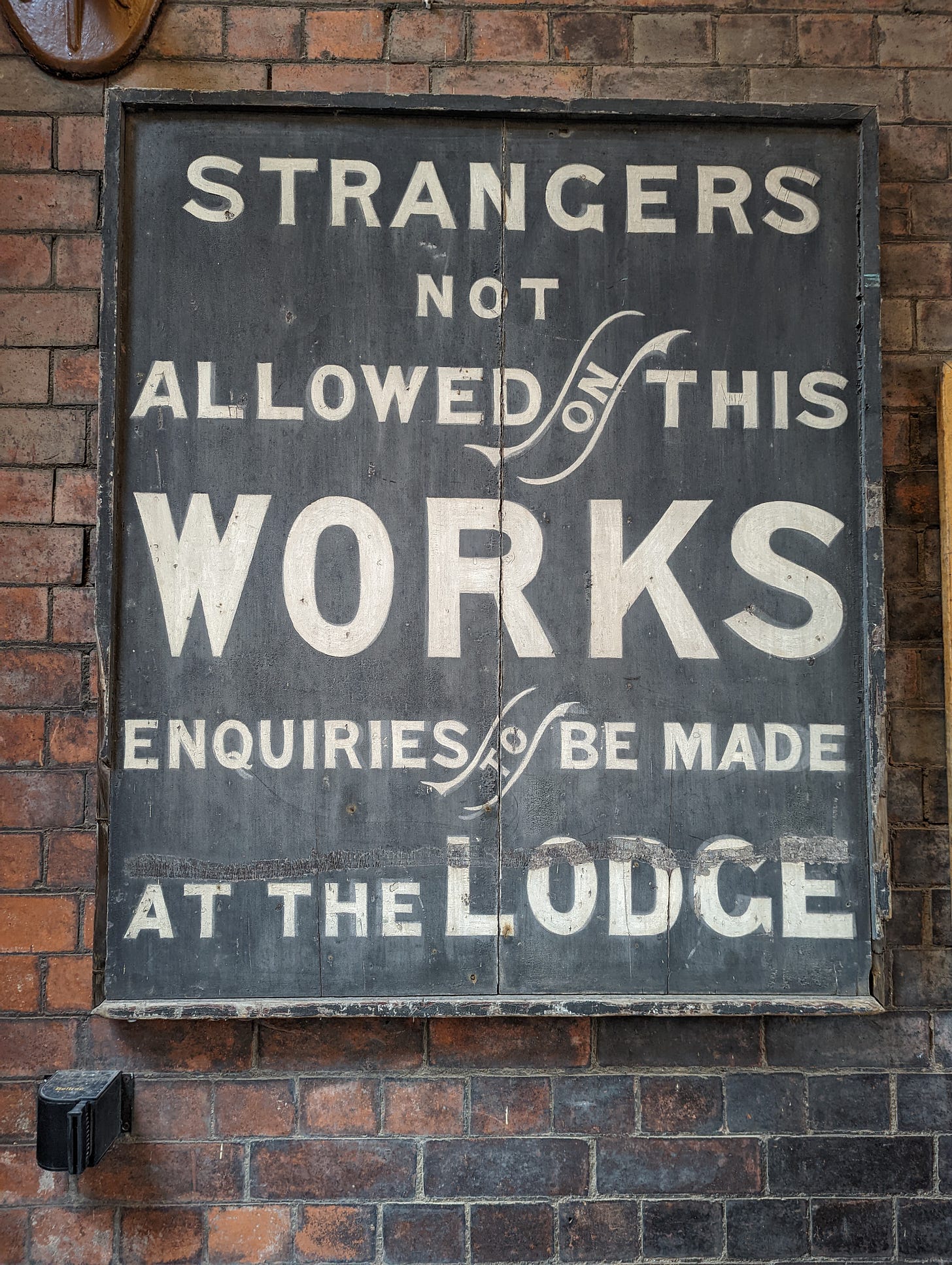

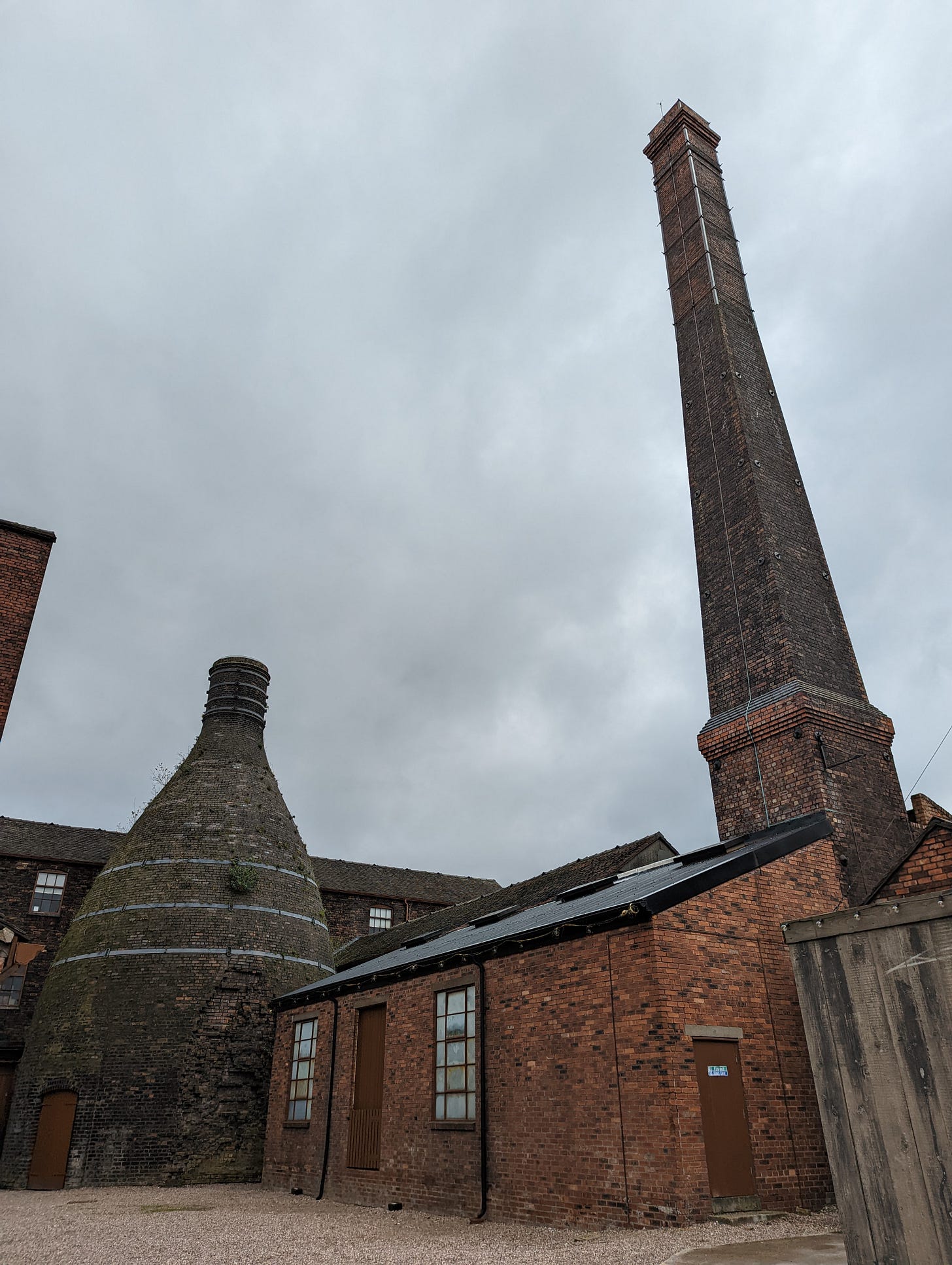

The ruins of old potbanks have their fascination, but it is wonderful to see the way that the history of these old potteries has been preserved at Middleport Pottery, which is a charming window into Stoke-on-Trent’s past. Featured in shows like Peaky Blinders, it is an intact and working Victorian pottery. I visited it the next week, with a friend who was staying for a couple of days.

I returned to New York just under a week ago and it has been wonderful to be back with Susannah again. We had a memorable trip upstate to the Bruderhof in Fox Hill last week, where we enjoyed Feuerzangenbowle and sang traditional German Advent songs with the Plough team. The journey back down the Metro-North Hudson Line was glorious too.

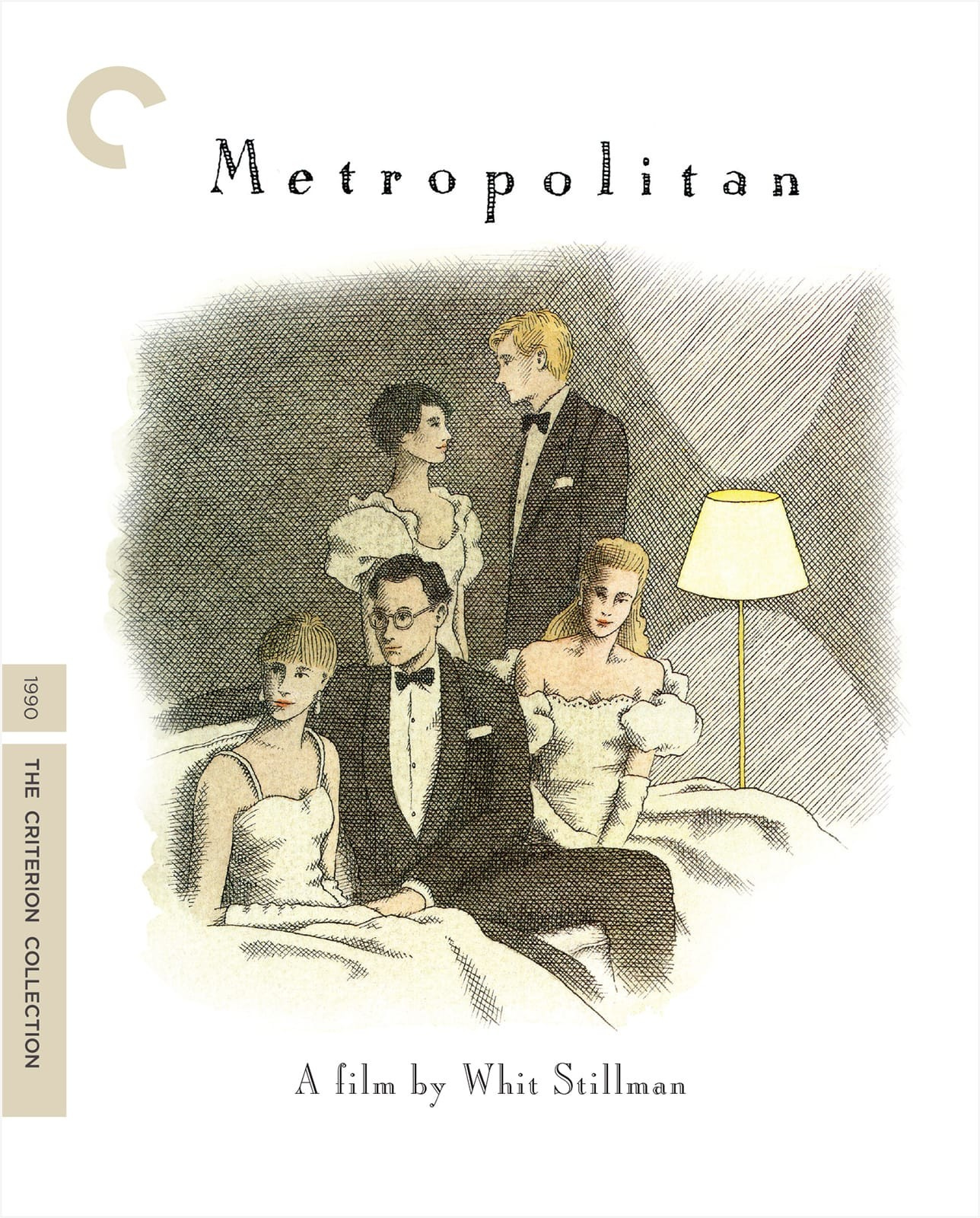

Susannah: I came back ten days before Alastair in order to go to the annual friend group First Sunday of Advent Metropolitan watch party. If somehow you’ve managed to not make this classic Whit Stillman film part of your Christmas traditions, this is a good year to start! Think Jane Austen in Manhattan in 1980.

Upcoming Events

❧ Alastair’s next Davenant Hall course, ‘Exodus and the Shape of Biblical Narrative’, is open for registration. He taught a course under this title a couple of years ago. However, as he will be teaching an intensive residential course for Theopolis on the Exodus later next year, he had to completely rework the course to ensure that there wouldn’t be overlap. The course is now designed to train students in skills of attentive biblical reading, honing those skills using parts of the Exodus narrative.

❧ Most of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Strengthening the ties to Genesis even further:

When Moses erects the Tabernacle in Exodus, he sets it up in eight stages, punctuated with a sevenfold repetition of "as the Lord commanded Moses". The eighth stage concludes with "and Moses completed the work." (Milgrom says somewhere that eight is a perfected seven, a point he connects to 50 days being a completion of 7 sevens.)

The sequence is introduced by the notice in 40:16 that "thus Moses did; according to all that the Lord commanded him, so he did," replicating exactly the notice in Gen. 6:22 that Noah followed God's instructions for the ark exactly (almost exactly, at least: YHWH substitutes for ELOHIM in Exo 40:16). The expression is used nowhere else in the OT, though a near identical expression is used of Moses, in Exo 7:6; 12:28, 50 -- the only difference being the substitution of "according to" for "as all."

Thanks for all your enlightening work. Being somewhat innumerate, the whole symbolic numbers thing in Scripture is mind blowing. I tried to unpack a small aspect of it here: https://scriptourer.substack.com/p/the-magic-number, but felt I was only scratching the surface! Look forward to a deep dive on the commentaries.