№ 56: Networks, Shortcuts, and Hubs

Stoke, Oxford, Dublin, and London

Alastair: It has only been a fortnight since our previous post, within which we chronicled our latest brief trip to the US. However, we have another very full couple of weeks coming up, so I thought that we should post something now, rather than have an insanely packed post after our return from our forthcoming France trip.

By the end of our US trip, both of us were eager to be back home in Stoke, enjoying some more settled life for a while. We were in Stoke for much of the time after our return—a welcome respite from the intensity of my travel commitments during our time stateside!—although we did have Oxford, Dublin, and London visits. This evening, weather permitting, we will be flying to Marseille, where we will be spending the next couple of weeks with my brother and his family.

Having arrived back in the UK on the Thursday, we did not have that much time to regroup before we were to travel down to Oxford on the Friday evening, where we were to spend a day with the Littlejohn family.

We wanted to spend some time with my parents before we did, so planned a meal with them before we were due to catch our train, around 8pm. Unfortunately, shortly before we were due to leave to go to my parents’ apartment, I received an email informing me that our train had been cancelled, but that we were welcome to take either the later or earlier train instead. The later train would have been too late, so we decided to take the earlier one. Literally a minute before we were due to board, I received another email, informing me that our original train was going to be running after all.

During their visit, our sister-in-law has coined an expression ‘HBP’ or ‘Highly British Person’, referring to the peculiarly British varieties of passive aggressive, officious, bureaucratic, inflexible, and unimaginative service persons one encounters in the UK. As we tried to leave Oxford Station, we had a run-in with such a person, one of the station staff, who refused to allow us to pass through the ticket barriers. Apparently, as we had not been on the correct train, we had to pay a penalty fare. I spent the best part of twenty minutes trying to reason with him, showing him the emails I had received from the train company, as I was completely unwilling to pay. Eventually, I managed to get the attention of another member of staff, who apologized profusely for the unreasonableness of his colleague and let us through.

That night we stayed with some good friends of mine from my time in Durham, introducing Susannah to them for the first time. After several years of being out of contact, we had reconnected online and caught up again in person at the recent Oxford Psalm Roar. I am hoping we will see a lot more of them in the future. [Susannah: This is the same family whose children, early in COVID, made a scripted and stagemanaged video for a Sunday school-from-a-distance project of 1 Samuel 5:1-5, which Alastair and I regularly quote to each other to this day: the pitying and somewhat condescending English child’s voice saying “poor Dagon” is a very memorable soundbyte; their (at the time) three year old brother played the statue of the god.]

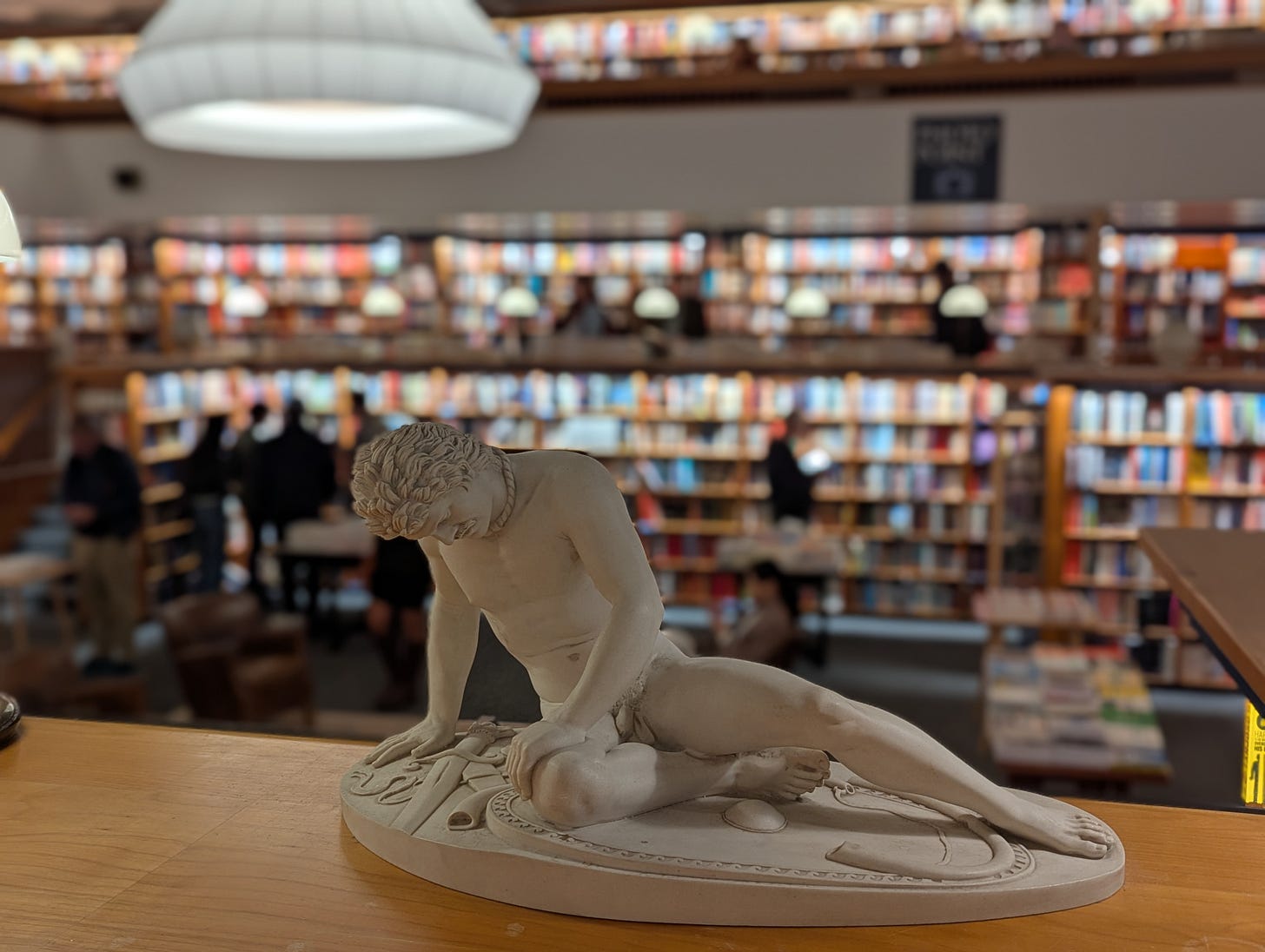

The next day, we had breakfast with our hosts and then went into the city to meet up with the Littlejohn family, who were visiting for the day. Rendezvousing with them and another mutual friend beneath the Carfax Tower, we made our way down to Christ Church, being waylaid at St Philip’s Books, one of our favourite second-hand bookstores.

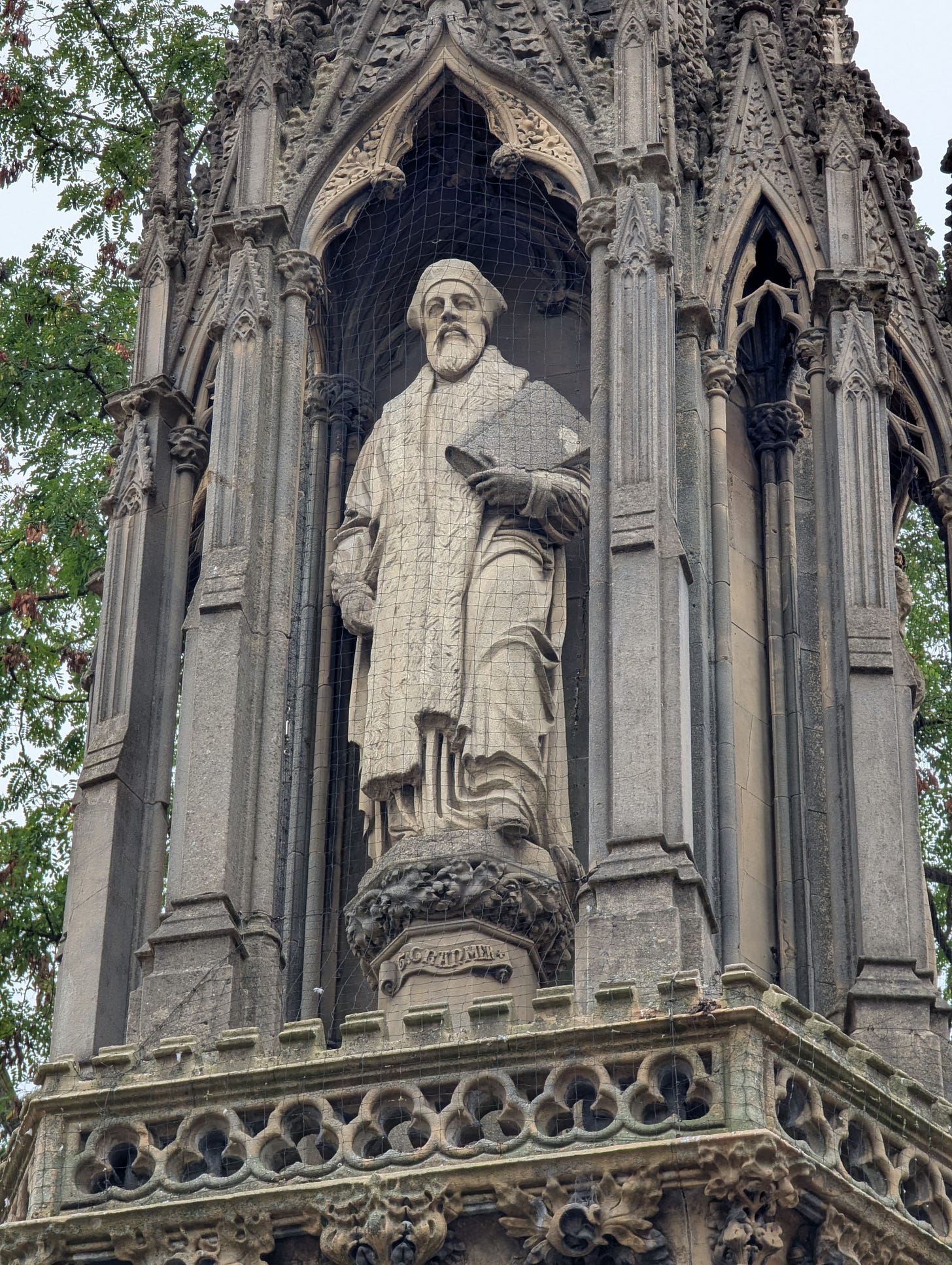

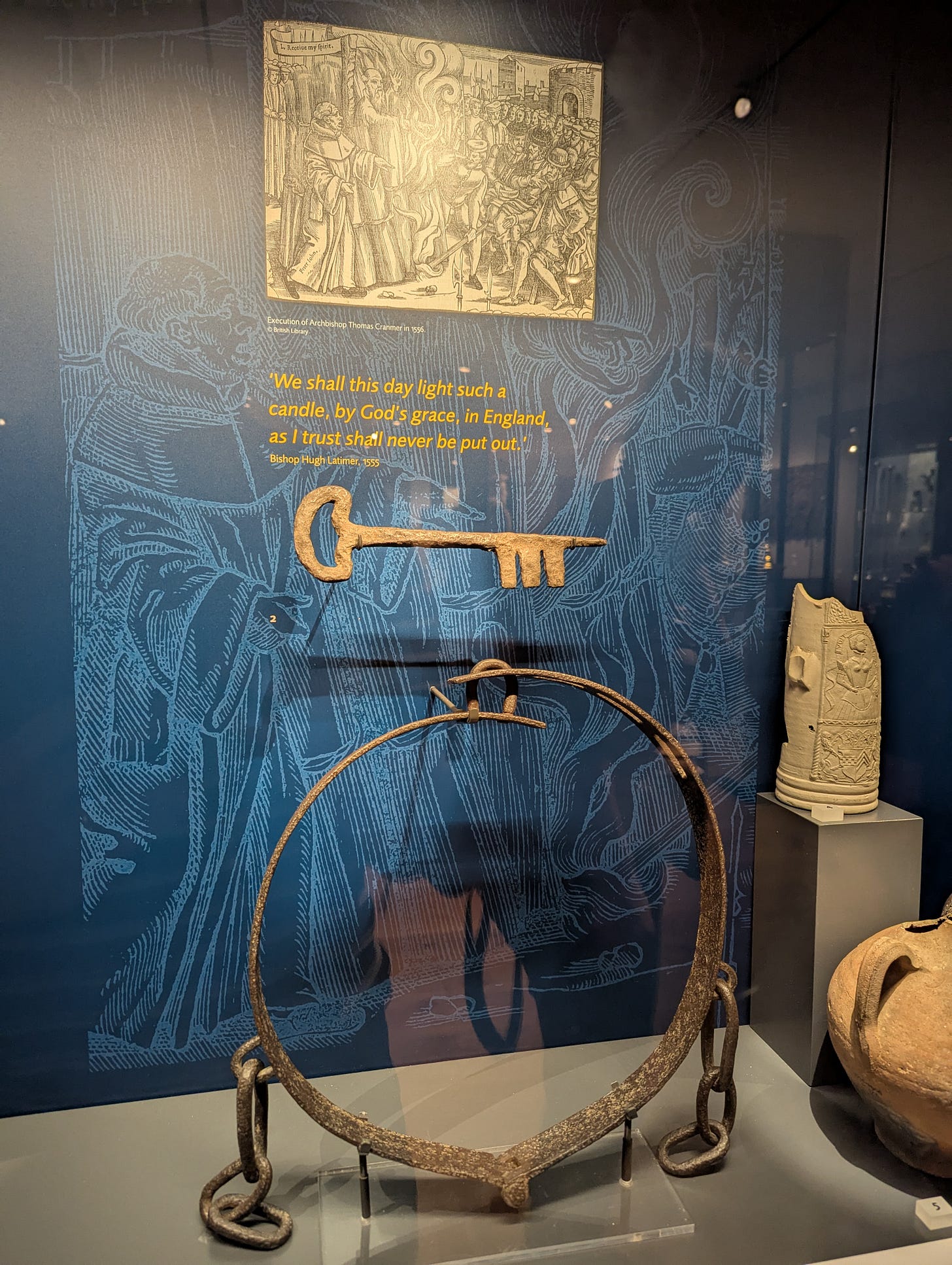

From there we walked past Christ Church and wandered around Oxford for a while, stopping at the Martyrs’ Memorial. The Martyrs’ Memorial commemorates Hugh Latimer, Nicholas Ridley, and Thomas Cranmer, three Protestant bishops who were tried for heresy and burnt at the stake in Oxford in 1555 and 1556. The Memorial was erected in the 1840s, in no small measure to inoculate people against the rising Tractarian Movement.

The Ashmolean Museum was next on our route. The Ashmolean Museum was Britain’s first public museum, opening in 1683. Its current building was also built in the early 1840s.

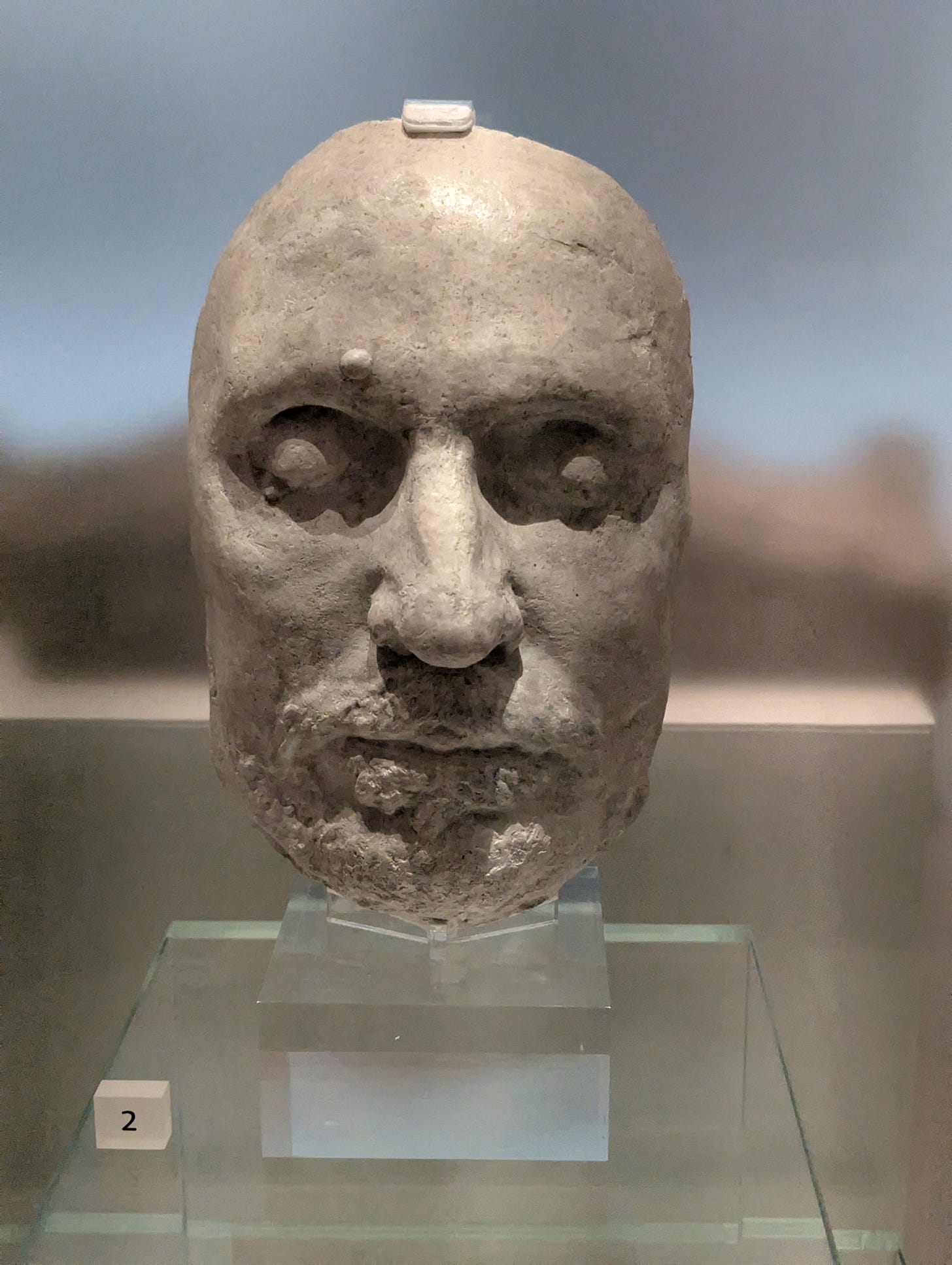

I had visited the Museum before, but had little recollection of it, so welcomed the opportunity to see it again. There were lots of fascinating things to see within it: Cromwell’s funeral mask, old musical instruments, the Alfred Jewel, items associated with the Oxford Martyrs, and many paintings.

We had a meal together in a pub, during which Oliver Littlejohn gave us an outstanding poetry rendition. Not able to resist another incredible bookstore, we went to Blackwell’s, where we spent another chunk of time.

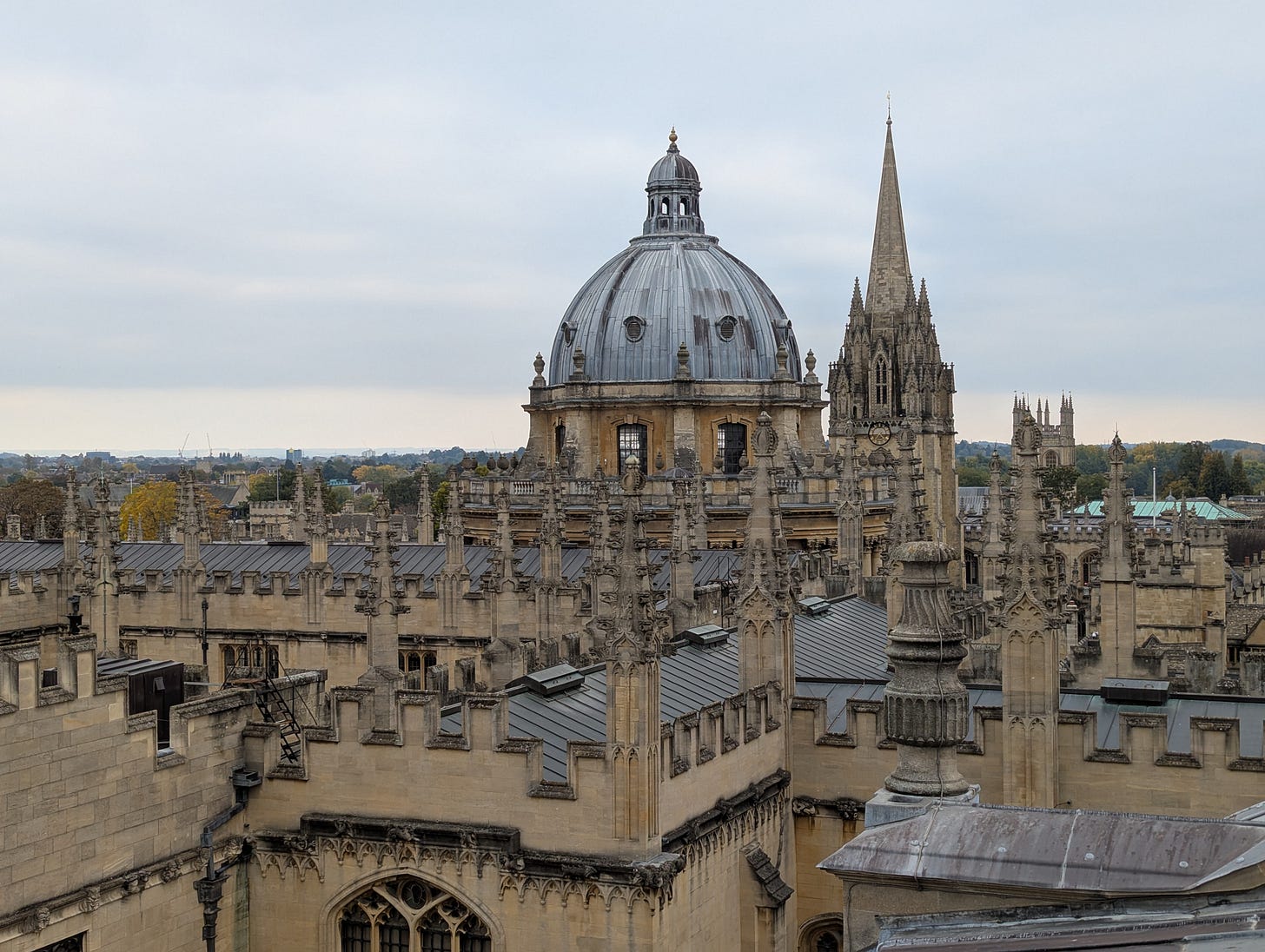

We wandered around the city further, taking in more sights, such as the Bodleian Library, the Radcliffe Camera, and the University Church of St Mary the Virgin. Oxford is such a charming city; taking in the entire place in a single day can feel overwhelming, so you just need to make the most of a few sites and plan to return at a later point.

Many of the other colleges were closed to visitors, but Magdalen (pronounced ‘maudlin’) College was open and we went in to look around. The college, founded in 1458, is next to the River Cherwell and the Botanic Garden.

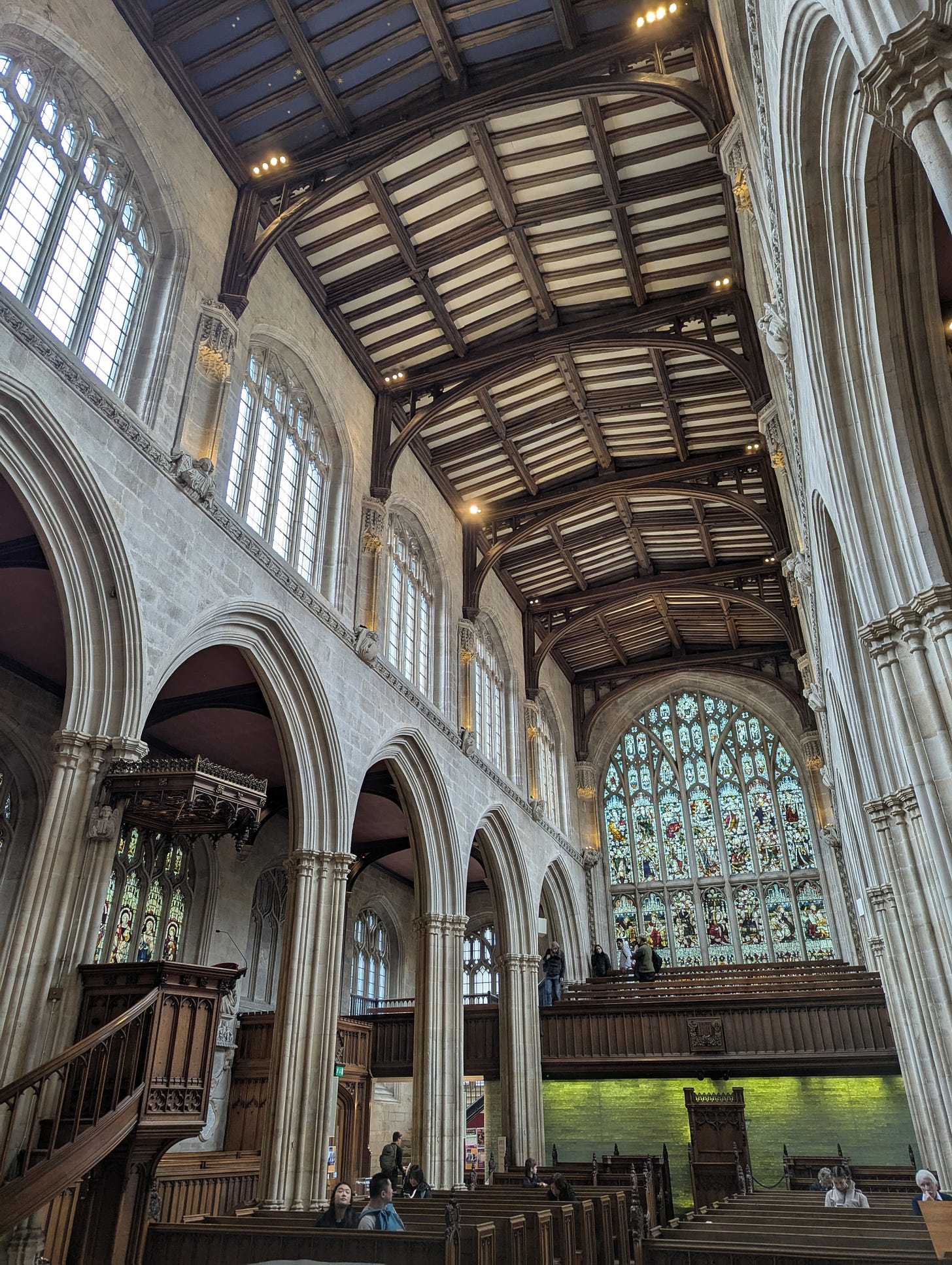

We went into the chapel, most of which was closed to visitors. However, we could see the main part of the chapel, with its superb vaulted ceiling, through the railings.

While walking through the cloisters, I was approached by a young woman, who recognized me. Apparently, she used to be a Plough intern, knows Susannah, and reads this Substack (if you are reading this, Ruby, it was a delight to meet you!). On a regular basis we have surprising and serendipitous encounters with people in random places who recognize us, or discover highly unexpected friends of friends, which is wonderful. [Susannah: I was delighted to learn that she is now working for Oxford University Press, and she says that the Plough internship was key in helping her get the job; working with out interns is always a highlight of my year — Ruby, keep in touch!]

We meandered around Magdalen for a while longer, going out to a small bridge across the River Cherwell behind the college, leading to Addison’s Walk. We then walked along the Grove next to the New Building, before leaving Magdalen.

Excursus on Magdalen by Susannah

Magdalen is the college where CS Lewis taught when he was at Oxford; Addison’s walk was a favorite haunt. On Saturday, September 19, 1931, Lewis invited Hugo Dyson and JRR Tolkien to dine with him in his rooms; after dinner they all went down to Addison’s Walk for a stroll along the Cherwell. As Lewis described it two days later to his friend Arthur Greeves,

We began on metaphor and myth—interrupted by a rush of wind which came so suddenly on the still, warm evening and sent so many leaves pattering down that we thought it was raining. We all held our breath, the other two appreciating the ecstasy of such a thing almost as you would. We continued (in my room) on Christianity: a good long satisfying talk in which I learned a lot: then discussed the difference between love and friendship—then finally drifted back to poetry and books.

This was about two years after he had become a theist — had begun believing in God in some way. He wrote just over a week later again to Greeves, saying “I have just passed on from believing in God to definitely believing in Christ — in Christianity. I will try to explain this another time. My long night talk with Dyson and Tolkien had a great deal to do with it.”

Just over two weeks after that, on October 18, he found time to write more fully, to explain himself to Greeves:

Now what Dyson and Tolkien showed me was this: that if I met the idea of sacrifice in a Pagan story I didn’t mind it at all: again, that if I met the idea of a god sacrificing himself to himself . . . I liked it very much and was mysteriously moved by it: again, that the idea of the dying and reviving god (Balder, Adonis, Bacchus) similarly moved me provided I met it anywhere except in the Gospels. The reason was that in Pagan stories I was prepared to feel the myth as profound and suggestive of meanings beyond my grasp even tho’ I could not say in cold prose ‘what it meant’.

Now the story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us in the same way as the others, but with this tremendous difference that it really happened.

This idea, of Christianity as True Myth, is one that has been profoundly important to me, as it has to many.

*** END EXCURSUS

Alastair: Next on the itinerary was the Sheldonian Theatre. Like Magdalen College, I had never properly visited it before, although virtually every time I have visited Oxford I have admired the iconic building from the outside. The building was one of the earliest works of Christopher Wren, the seventeenth century architect famed for designing St Paul’s Cathedral, the Old Royal Naval College in Greenwich, and parts of Hampton Court Palace.

We made it in just as it was closing. We did not spend long in the interior of the theatre, as our plan was to look out from the cupola. I did wish that we had been able to spend more time, as the interior of the theatre is spectacular. The vast and large flat ceiling has a large allegorical representation of the descent of Truth upon the Arts and Sciences and the expulsion of ignorance.

In its day, the roof was an innovative design and the building was a landmark architectural achievement. Although there were not timbers sufficiently long to span the seventy-foot roof, rather than use a tried and tested Gothic roof, Wren opted for the more recent geometrical flat floor grid, developed by John Wallis. Load-bearing columns would have undermined the classic theatre appearance that Wren desired. Both the roof and its cupola were later rebuilt according to slightly different designs, but one can still admire Wren’s vision.

After a brief look around the interior of the theatre, we ascended the steps to the cupola, which affords splendid views out over the city of Oxford. It was an overcast day, so our views were not what they could have been, but we were impressed nonetheless. I will doubtless return on a future occasion when the weather is better.

We descended the stairs and made our way past the Lamb & Flag and the Eagle and Child pubs, returning into the city centre, where our mutual friend, a deputy headmaster in a nearby school, joined us again.

[Susannah: The Eagle & Child is the primary hangout of the Inklings, the semi-club/writers’ group/group of friends to which Lewis and Tolkien belonged. Alastair and I went there in February 2020, about 24 hours before we mutually admitted that we were not exactly just friends, that this might be something more. As with so many places, it didn’t survive COVID, and has been closed the last few times we’ve visited.

Happily, it has been purchased and will be opening again as a pub.

Unhappily, the person it has been purchased by is Larry Ellison, the co-founder of Oracle and second only to Elon Musk in both wealth and commitment to what seems to me to be the most sinister version of the Silicon Valley/DC axis; the NICE has, in other words, bought the Bird and Baby.]

We had a late afternoon tea, before dashing back to the station, as the Littlejohns were running late for their train. Susannah and I hung around the station area for a while, before catching an earlier train back to Stoke.

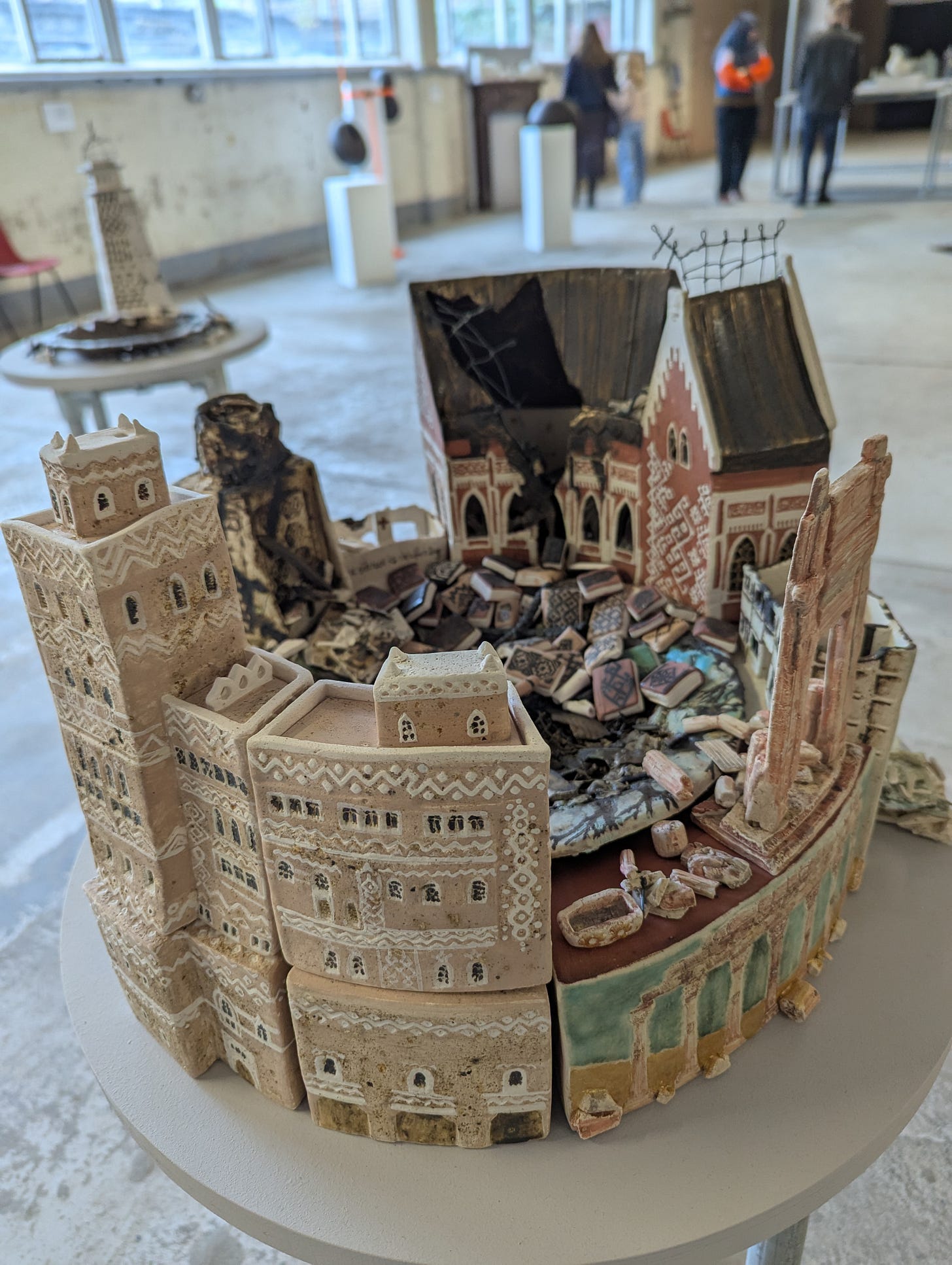

It was the British Ceramics Biennial and the Spode Factory was hosting an exhibition of works of pottery. I was eager to see it, but, having been away from our home in Stoke for most of the past month, Susannah was insistent that she wanted to spend the whole day enjoying maximal hygge, so after church I visited the exhibition by myself. [Susannah: We have developed a concept of coziness maxxing as a way to approach the English fall and winter. We call it the bygge hygge.]

There was a fascinating variety of exhibits: more ideologically-framed pieces with points to make about social or political issues such as homelessness or the environment, technical explorations of the potential of ceramic media, imaginative, whimsical, and beautiful designs, and some playful and thoughtful engagements with traditional styles. Even among the kinds of exhibits that would typically hold limited interest for me, there was much to impress and appeal.

When I first moved to Stoke as a teenager from Ireland, I found the city quite unappealing and pottery was really not something that enthused me. Compared to the immediate natural beauty that surrounded us in Clonmel, Stoke felt urban and dull, with various of the ills of the declining post-industrial Midlands city that one would seldom encounter in an Irish country town. However, while my first impressions were not without any grounding in reality, they were far from the whole picture and over the last two and a half decades I have come to enjoy Stoke immensely: it is a city with countless wonderful places to be discovered by those who love her. Living here, I have also grown to appreciate the brilliance of the science, craft, and artistry of pottery, for which Stoke has been world-renowned. Going around the Biennial exhibition, I was reminded of how much Stoke has given the world (keep following this Substack for continued steady Potteries propaganda) and how, even though much diminished from its past heights of industry, it continues to innovate and produce beauty.

Like so many other pottery factories in Stoke, the Spode factory closed during the time since I moved to the city. However, the exhibition used several of its large areas for its displays, which, in some cases, used the spaces themselves to very good effect.

After having looked around the exhibition, I went into the main Spode museum, which had an exhibition on the Willow pattern, in addition to its more regular displays. Returning home, I insisted that Susannah visit the next time we went.

As our meal with them had been cut so short on the Friday, we arranged to have another meal with my parents on the Monday. Knowing that he—and I—would greatly enjoy it, I made a banoffee pie for my father.

The next day, in the hour and a half before a Theopolis recording session, I persuaded Susannah to visit the British Ceramics Biennial with me. I think she enjoyed it more than she had expected. Jane Perryman’s Meadow was, I think, the standout for us. Twenty years ago, Perryman obtained an acre of land formerly ravaged by chemical-heavy agricultural and planted it with wildflower seed. It has since been accorded private nature reserve status. From the plants growing in the meadow, Perryman produced an array of dyes, using them to colour fired ceramics. The result, especially for Susannah, still on her foraging kick, was quite inspiring!

On the Thursday, I returned to The Longest Yarn exhibition in Stoke Minster with my parents. As we had some very full days coming up before our Marseille trip, I thought it might be my last opportunity to spend time with my parents for a few weeks. I shared my experience of visiting The Longest Yarn in our previous Substack, but revisiting it with my parents gave me the chance to see many aspects of it closer.

My parents had seen an earlier project, which recreated scenes from D-Day in knitted form. I had not realized that The Longest Yarn in Stoke Minster was the second project of the kind. The original The Longest Yarn is currently touring the US. I hope I will have the opportunity to see it myself at some point.

The next day, Susannah and I got up at 5:30am and went to Manchester Airport, from where we flew to Dublin. A few years ago, my father introduced Susannah to a young woman who lived just up the road from us. She and Susannah became good friends and, during their friendship, she started a relationship with a young man from Ireland. They got married last Saturday.

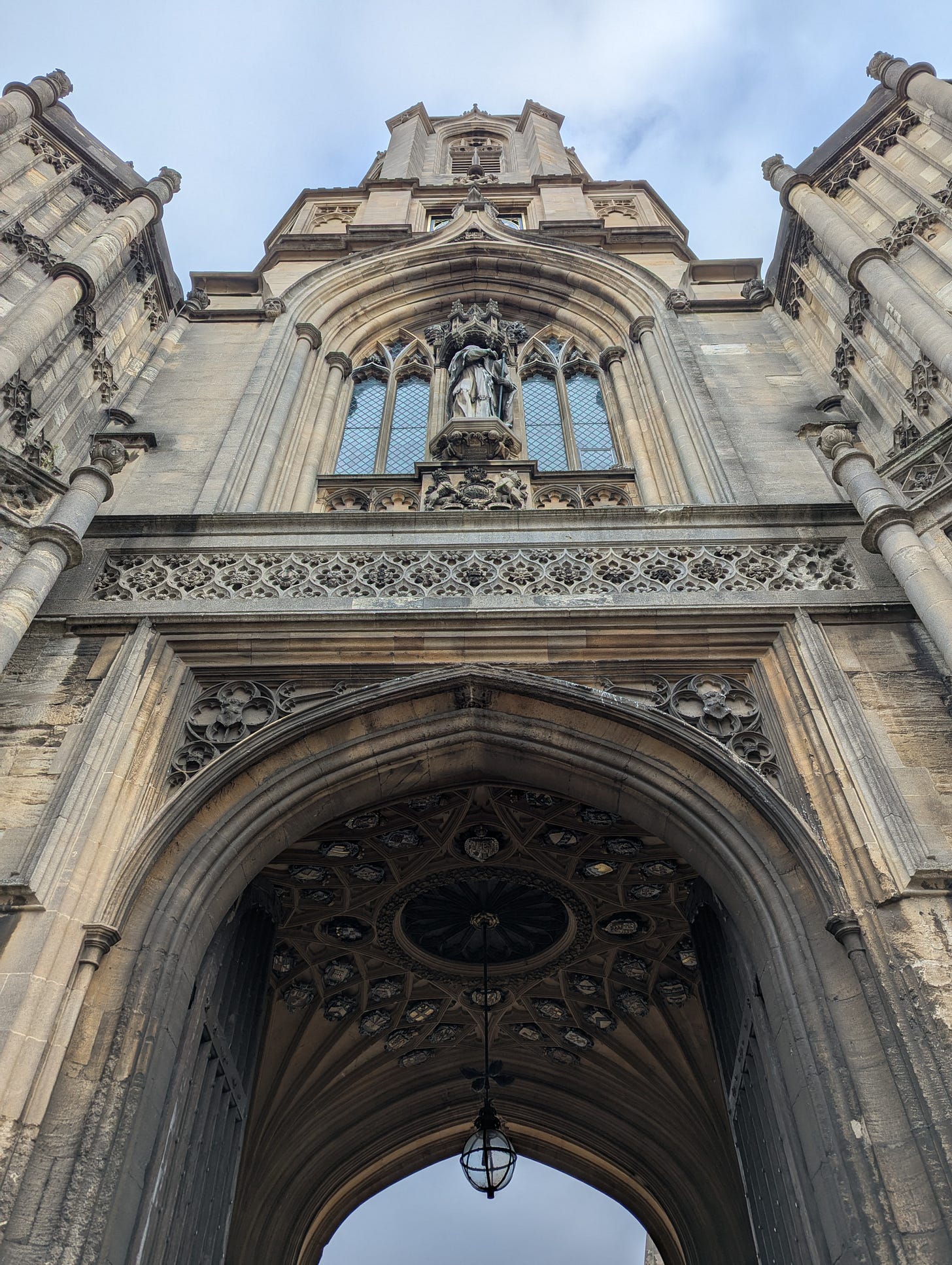

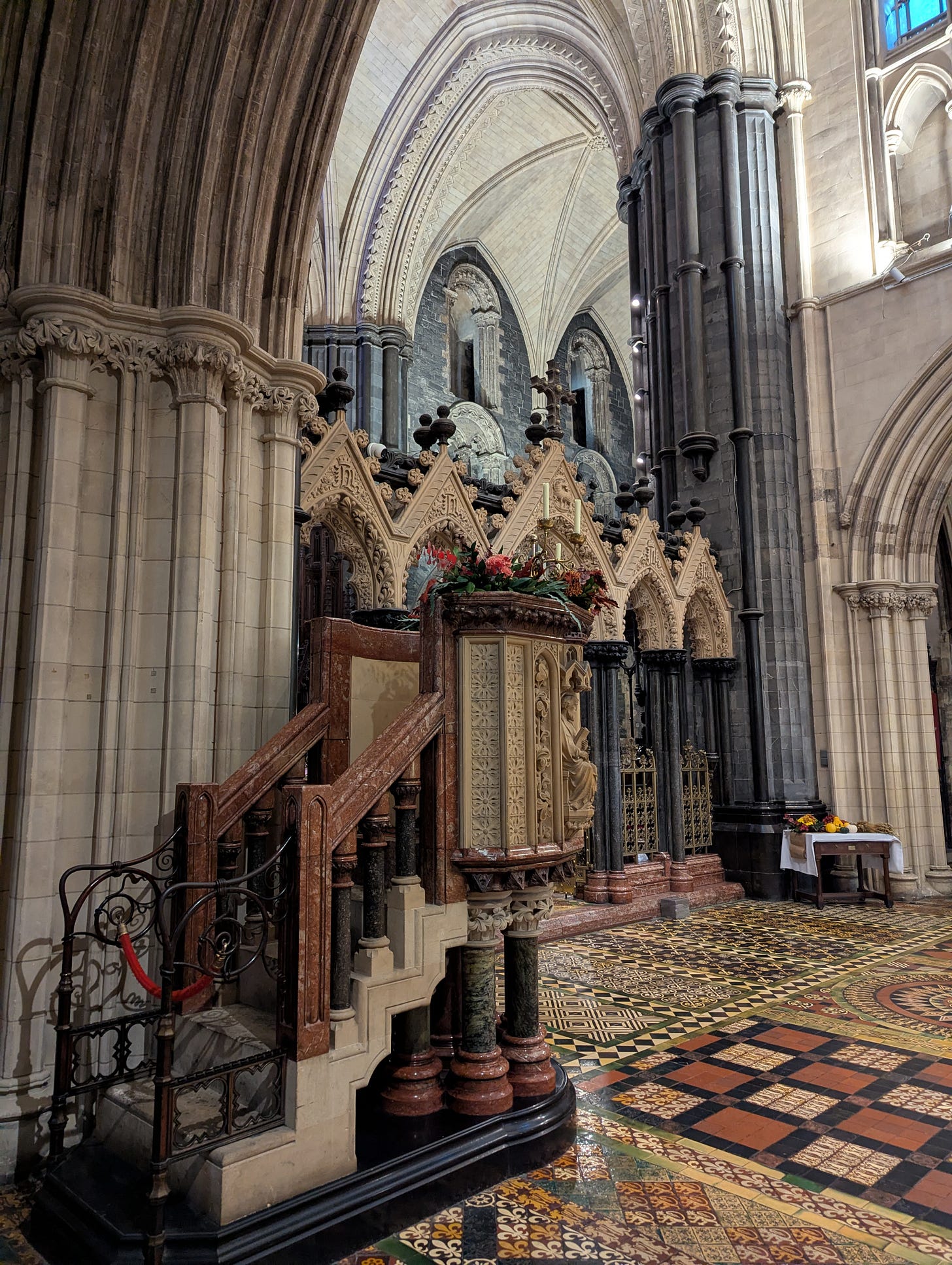

We had a couple of hours before the wedding started, so we got a taxi to Christ Church Cathedral. Although I had visited St Patrick’s Cathedral before (including at the start of our Ireland trip last year), I had not, at least to my recollection, visited Christ Church.

The cathedral is the older of the two Dublin cathedrals, being originally of Viking construction, dating back to the early eleventh century. During the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland under Strongbow in the late twelfth century, the cathedral was substantially rebuilt. Strongbow himself is buried within it.

Christ Church Cathedral was in the strange position of sharing cathedral status for the Dublin diocese with St Patrick’s. The relationship between the two buildings has changed over the years. St Patrick’s is now the national cathedral of the Church of Ireland, while Christ Church is the diocesan cathedral of Dublin and Glendalough and of the United Provinces of Dublin and Cashel.

Ecclesiastical boundaries in Ireland and their history can be a little confusing to the uninitiated, especially when one also considers Catholic boundaries. Although the Church of Ireland is very much a minority—albeit formerly established—church, it has two cathedrals in the capital, while Catholics have had no cathedral in Dublin since the Reformation. As Christ Church was designated as the official Dublin cathedral by the pope in the twelfth century and this status has not been revoked and no other cathedral has been designated, the principal Catholic church in Dublin is St Mary’s ‘Pro-Cathedral’.

While I prefer St Patrick’s as a building, I was very impressed by Christ Church, not least on account of its importance for Christian history in Ireland. One of the most striking features of the cathedral from without is the stone bridge that connects it to the former synod hall, which now houses a museum of medieval Dublin. The cathedral also contains more statuary than I recall in St Patrick’s.

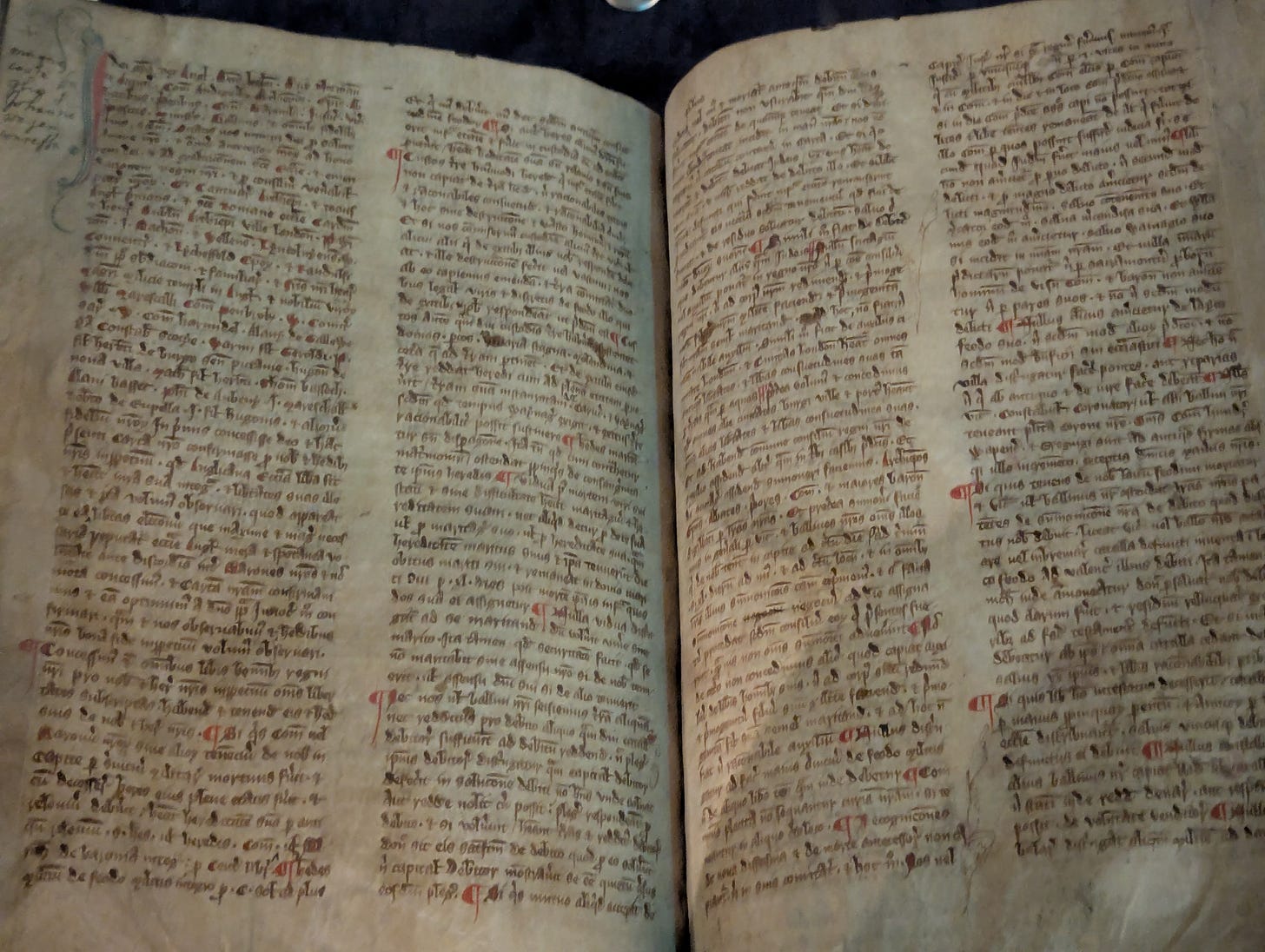

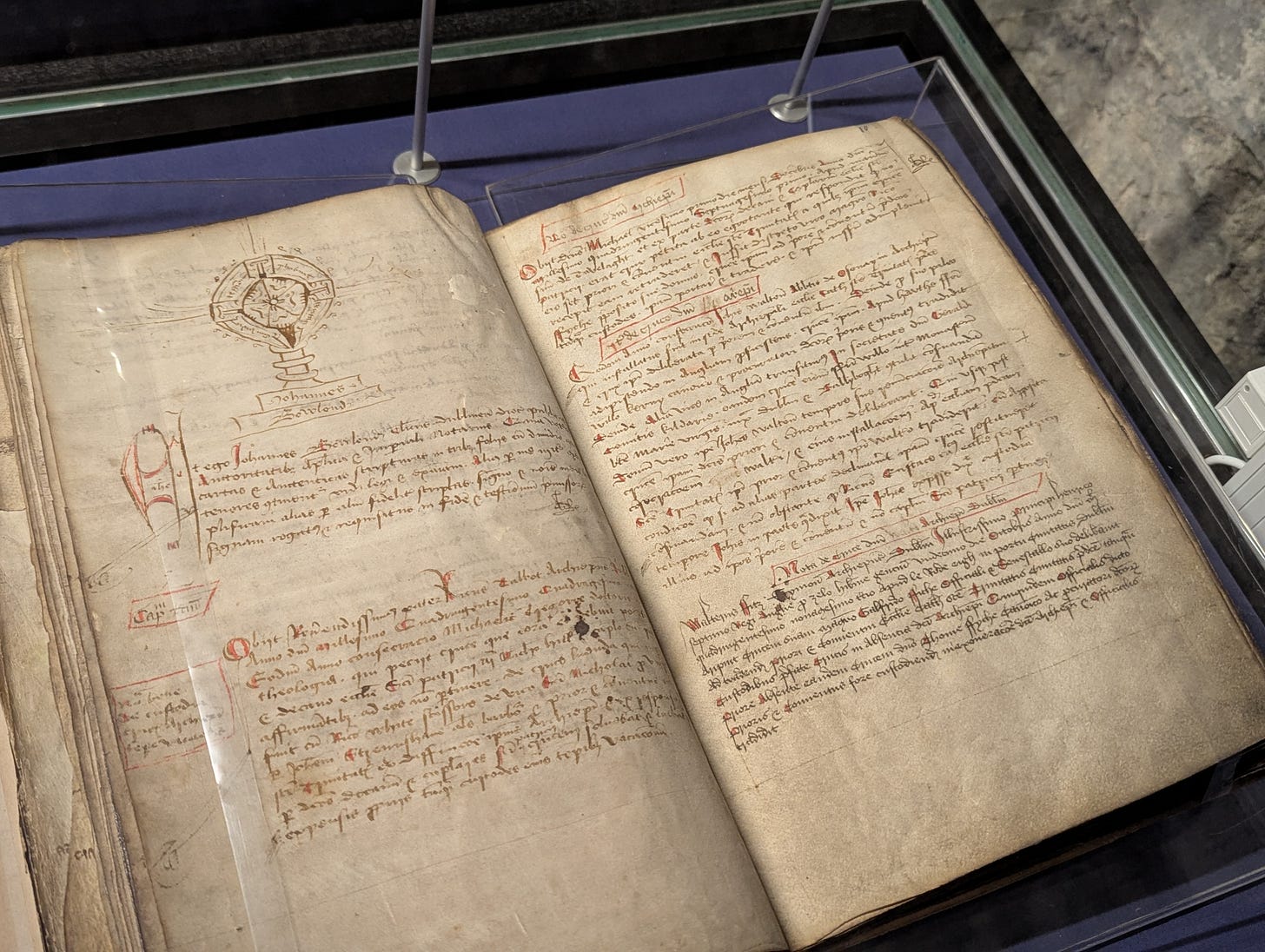

The crypt is the largest cathedral crypt in Britain or Ireland, 63.4m in length. It now houses various treasures of the cathedral. Christ Church has its own copy of the Magna Carta, some spectacular altar goods, along with several other remarkable treasures.

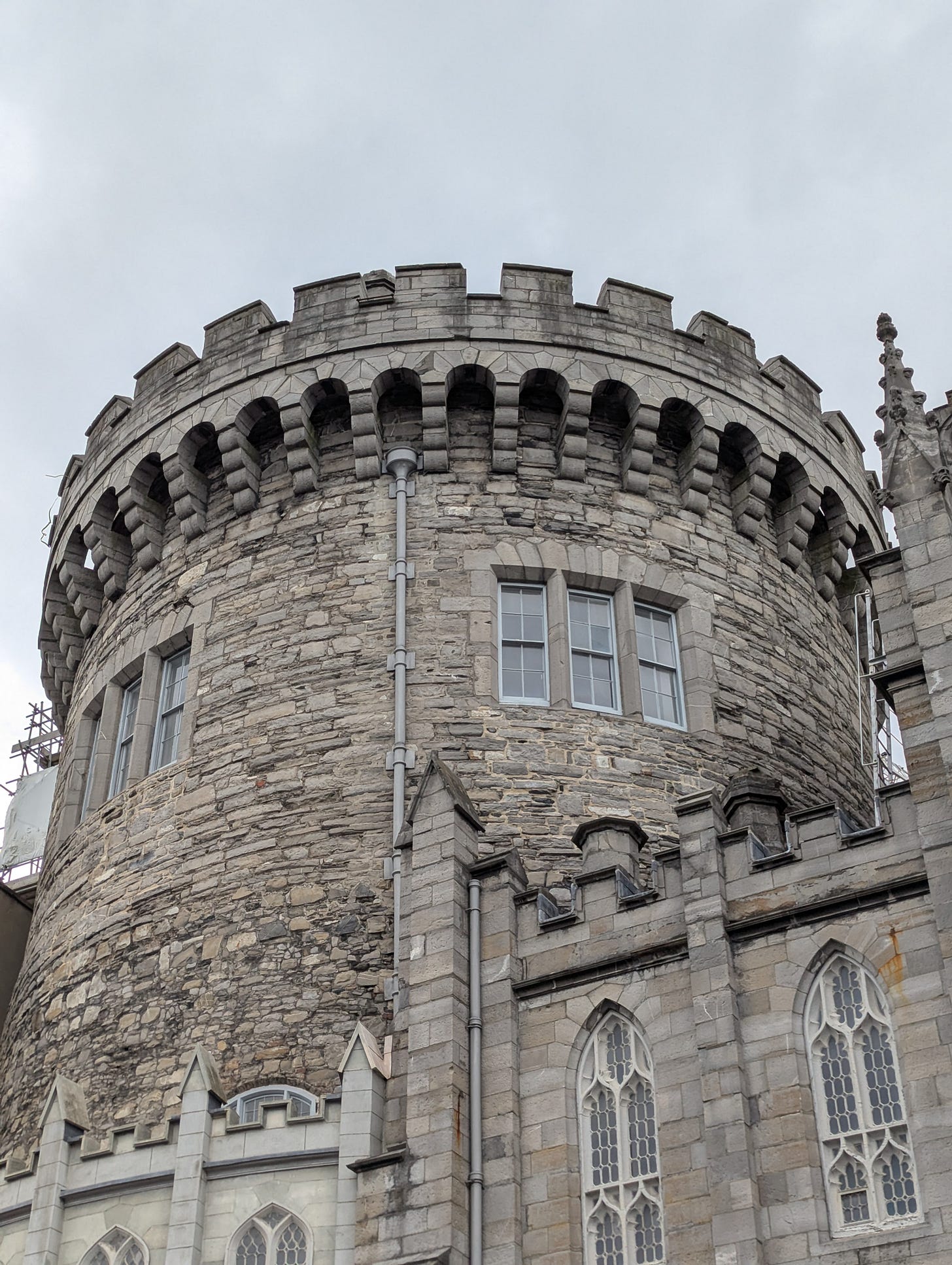

From Christ Church we wandered around to Dublin Castle. We did not have the time to go in, but we saw some of it from outside. I cannot recall ever having gone inside as a child; that will have to be something that we do on a future visit.

After seeing some of the area around Dublin Castle, we made our way towards St Patrick’s Cathedral. Along the route, we were impressed by some new public housing with terracotta plaques depicting scenes from Gulliver’s Travels. Jonathan Swift used to be the dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral, so it was wonderful to see Dublin celebrating that historical connection.

We did not go into St Patrick’s, but we saw it from outside.

The wedding was held in St Kevin’s Church on Harrington Street. We admired some of the beautiful doorways for which Dublin is known along the route. Dublin can be a very pleasing city. My childhood memories of the city are mostly of traffic jams, but exploring it on foot was a very relaxing experience.

St Kevin’s is a strikingly beautiful building in a Gothic Revival style, designed by Edward Pugin, the eldest son of the famed Augustus Pugin, who designed the Elizabeth Tower (better, if inaccurately, known as Big Ben) and much of the interior of the Palace of Westminster. Edward and his brothers Cuthbert and Peter very much continued their father’s architectural work. The wedding was a Latin Mass service, the first such wedding I had experienced. It really was an incredible spectacle, although it did make me feel very Protestant!

Although it had involved a very early morning and further travel after an exceedingly intense period of travel, we were both so glad to be able to make our friend’s wedding. Neither of us had properly met her new husband before, and appreciated making his acquaintance. At the reception, we also talked at length with her maid of honour and the man with whom she came, who had also travelled over from Stoke. We had to leave before the meal, flying back to Manchester and getting home for a very late dinner. Getting to sleep in our own bed has felt like a rare treat over the past month!

After church the next day, we dropped over to my parents and spent a short time with them, as we were having Susannah’s brother and his family with us over the next few days, so would not have the chance to see them again before leaving.

Early Monday afternoon, Toby, Langan, and Oona arrived. After they had caught their breath, we went out to the Trentham Monkey Forest. I had visited the Monkey Forest with Susannah once before. On the wider Trentham Estate, adjacent to Trentham Gardens, it contains about 140 Barbary macaques. The monkeys roam free in the beautiful surroundings of the forest, which, with much of the rest of the Trentham Estate, was largely landscaped by the famed Capability Brown.

We did not walk all the way around the Monkey Forest on this occasion, remaining in the central area and watching the feeding of the monkeys. I continue to find it surreal that Trentham is home to about half as many Barbary macaques as the Rock of Gibraltar, which is famous for them.

The exuberance and the antics of the monkeys were clearly contagious, as Oona was soon jumping enthusiastically in puddles. [Susannah: Puddles AND monkeys! And BABY monkeys! I think Oona enjoyed herself. Certainly I did.] We tried, eventually successfully, to get into Trentham Gardens from the Monkey Forest side, though not before having another run-in with the inflexibility of much British service culture in the attempt.

Having Toby, Langan, and Oona in Stoke was wonderful. Our life is divided between homes on both sides of the Atlantic, but that divide feels much less pronounced when we have shared our life on both sides with the people we most care about.

After a relaxed start to the day on Tuesday, we caught the train to London. Susannah was giving a talk in the evening, while Toby, Langan, and Oona were returning to their accommodation in Shoreditch. As we were going to be staying with them for the next couple of days, I went with them to the Airbnb and dropped our bags off.

I returned to South Kensington, wandering around and taking in some of the architecture, the Natural History Museum, the Albert Memorial, and the exterior of the Royal Albert Hall.

After half an hour of this, I met up with Brad Littlejohn and our friend Rhys. We had a pub meal and caught up, as we had not seen each other in person for a year.

Brad had discovered that there was going to be a performance of Mahler’s first symphony in the Royal Albert Hall, booked tickets for his family, and invited Susannah and me to join him. Susannah was unable to go, as she had her talk, but I jumped at the opportunity.

It was my first time going to a performance in the Royal Albert Hall. We were seated high up, largely by ourselves. I had bought a ticket for the nearest seat to them that I could. However, I was two rows above them and there were empty seats next to their party. At the intermission, I moved down to join them.

While Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony (Symphony No. 2) is my favourite of his works, his first symphony is incredible and hearing a performance of it in the Royal Albert Hall was a huge treat, and more so because it was unanticipated: I only bought my ticket a couple of hours beforehand. The four Littlejohn children all sat through the entirety of the performance, especially impressive in the case of the youngest.

Excursus: Susannah’s Talk, by Susannah

The talk went, I think, very well — at least people laughed at the funny parts. It was part of a series organized by Jenny Sinclair of Together for the Common Good. I’ll link it in the next Substack. The gist was a critique of AI from a humanist/Christian humanist perspective. I focused on two things:

First, the way in which the existence of AIs tends to confuse people about what it is to be human and what it is that distinguishes humans from machines.

Second, the ways in which bad uses of AI have the potential to gut major aspects of human experience, the experience of being a maker made in the image of God who is a maker, an understander made in the image of God who understands. More to the point, I am interested in the ways in which we can choose in our own lives and as a culture to go a different way.

The talk was followed by a Q&A from both in-person audience and Zoom viewers, and then by a dinner for around forty people with a semi-structured conversation. It was a really lovely time, with several good friends in the audience and many people I hope to run into again.

***End Excursus

The next morning, Susannah and I returned to South Kensington, meeting up with the Littlejohns for breakfast. Toby, Langan, and Oona were going to rejoin us later.

The Littlejohn children had visited the Victoria and Albert Museum already, but were very eager to spend more time there. The Cast Courts, which contain reproductions of some world-famous sculptures, were perhaps the greatest draw.

Certain parts of London are swamped with tourists. However, get slightly off the main tourist trails and one can see incredible places with few tourists around. Contrasted with the much more popular British Museum, the Victoria and Albert felt virtually empty. Without the crowds, the visitor’s experience can be a lot more relaxed and less hurried. The British Museum has a strong claim to be the world’s greatest museum; it is the first public national museum, the museum with the largest permanent collection, and contains some of the most significant artefacts in the world (e.g. the Rosetta Stone). However, if you have a few hours to spare in London at some point and want a more leisurely museum experience, your time might be better spent in the Victoria and Albert.

The Cast Courts feature a replica of Michelangelo’s David, Trajan’s Column, and a copy of Pórtico de la Gloria, the entrance to the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral. Besides these, there are reproductions of some incredible monuments, statues, reliefs, pulpits, tombs, and paintings. While they are reproductions, the Cast Courts allow visitors to see world famous sculptures from angles from which they could not see the originals.

While we did not have the time to have coffee there, we looked inside the café in the Victoria and Albert. A strong case could be made that it is the grandest café in the UK, reminiscent of some of the greatest cafés in Vienna.

[Susannah: The café is decorated exclusively with products of William Morris’ workshop, and the spirit of Morris and Ruskin and the Arts & Crafts movement is one of the main animating principles of the museum. I would describe the museum as dedicated to craft rather than fine art, to art as it is experienced and appropriated for semi-bourgeois home life, in a very typical Victorian mode. “Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful,” Morris’ general maxim for living and decorating, is not bad advice for today as well.]

Parting with the Littlejohns, we went to the Tower of London, where we were due to meet with Toby, Langan, and Oona.

I have seen the Tower of London from outside on dozens of occasions but had never visited. Toby and Langan treated us to tickets and we spent the majority of the afternoon there.

The Tower of London was built by the Normans in the eleventh century after the Conquest. William the Conqueror built the White Tower, the stone keep at the heart of the citadel complex. The castle served as a royal palace, a fortress, and a prison. Over the centuries following its Norman founding, it was extended considerably.

Entering the castle complex, we saw some of the ravens which are associated with it. According to legend, if ravens leave the Tower of London, the kingdom will fall. To ensure that this never happens, at least six ravens are kept in the Tower at all times, under the oversight of the Ravenmaster, one of the iconic Yeoman Warders (better known as Beefeaters).

Within the central White Tower, there are displays of medieval armour and weaponry. While the others went on to the Crown Jewels exhibition, I spent some time exploring the Tower.

The Crown Jewels exhibition was next on my route. The Tower of London has housed the Crown Jewels and other royal regalia since the thirteenth century. During the Commonwealth, Cromwell had the jewels and the metal of the royal crowns and other regalia destroyed or melted down. At the time of the Restoration, replacements were made according to drawings of the originals. In 1671, Thomas Blood attempted to steal the Crown Jewels and nearly succeeded. He bound and gagged the Jewel House keeper, but his plan was foiled by the unexpected return of the keeper’s son.

Susannah’s Excursus on Thomas Blood

Thomas Blood, who called himself Colonel Blood (he was not a colonel), is one of the most absurdly Restoration people in the Restoration. Born in Ireland in 1618, when the Civil War broke out he was originally a Royalist and then switched sides to support Cromwell, who gave him a large estate in Ireland and made him a Justice of the Peace.

After the Restoration of King Charles II, Blood hatched a conspiracy to storm Dublin Castle, kidnap the First Duke of Ormond for ransom, and usurp the government. The plot was foiled and Blood fled to the hills to hide, escaping later to Holland.

In 1670 he returned to England (despite being, obviously, a wanted man), set up as an apothecary in East London under the name Ayloffe, and, apparently in a fit of pique, made another plot to kidnap the Duke of Ormond. He and his cronies attacked Ormond while he was riding down St. James’ Street, tied him up, and were going to take him to Tyburn to hang him (why Tyburn? unclear. It was the place where criminals were executed but if you’re carrying out a vendetta surely there are better ways; in any case, on their way to Tyburn, Ormond managed to escape.) Somehow the secret of Blood’s instigation of this plot was kept and he escaped prosecution.

Six months later he visited the Tower of London disguised as a clergyman with a female accomplice posing as his wife. She pretended to have stomach trouble and the Keeper of the Crown Jewels invited both of them up to his own apartment, where his wife cared for the “parson’s” “wife.” The next day, Blood brought the Keeper’s wife several pairs of gloves as a thank you, and took the occasion to strike up a friendship with them. The couples became close and Blood claimed to have a nephew who would make a perfect husband for the Keeper’s daughter.

The Keeper’s wife organized a dinner at which the fictitious nephew was to be introduced to the Keeper’s daughter, and as part of the festivities, and after (one imagines) a certain amount of wine had been drunk, Blood convinced the Keeper to bring out the Crown Jewels to show the company. He did so, at which point Blood, his “wife,” the fictitious nephew, Blood’s brother in law, and an accomplice named Parrot attacked the Keeper, hitting him on the head with a mallet and tying him up, and stole the jewels. Blood used the same mallet he had hit the Keeper on the head with to flatten the Imperial State Crown of Charles II and hid it beneath his clerical coat. His brother-in-law cut the royal scepter in two so that it would fit in his bag, and Parrot stuffed the Orb down his trousers. I am not making this up.

At this point, the Keeper’s son, just then returning from military service in Flanders, walked in on the scene, and also the Keeper managed to get out of his bonds.

The conspirators now attempted to escape, running down to the Tower Wharf on the Thames via St. Catherine’s Gate. The yeoman of the guard, alerted, got off a couple of shots at the thieves (though one guardsman was too scared to fire) and the thieves returned fire, but everyone missed. Then the Keeper’s son’s brother-in-law showed up and chased them down with considerably more effectiveness than the guards. Blood shot at him as well but missed. Seeing the jig was up, Blood yelled “It was a gallant attempt, however unsuccessful! It was for a crown!” and surrendered.

Blood was questioned but said that he would not answer to anyone but the King. Somehow this worked, and he was consequently taken to the palace in chains, where he was questioned by King Charles. Apparently part of the conversation consisted of Charles saying essentially “Those jewels are worth £100,000,” (£16 million in today’s money) and Blood saying “personally I don’t think they’re worth more than £6000.” (£947,000.) (This was complete nonsense; they were in fact valued at the amount the King claimed they were.) “What if I should give you your life?”, the King said, to which Blood replied, “I would endeavour to deserve it, Sire!”

Somehow this worked. Blood convinced the King to not only pardon him and all his fellow conspirators, but to grant him lands worth £500/year in Ireland. (Nearly £80k/year today.)

In the years that followed, Blood became a popular man about town in London and made frequent appearances at Court. People would hire him to advocate their cases to the Crown.

The Duke of Ormond was, as one might imagine, disgusted.

***END EXCURSUS

As Oona needed to return for a nap shortly afterward, we got jam and scones in the café before they left us. Susannah and I then went on to explore other parts of and exhibitions the castle.

For much of its history, the Tower of London housed the Royal Menagerie. The king received exotic animals as gifts from other monarchs—a polar bear from Haakon IV of Norway, an elephant from Louis IX of France, etc. By the 1820s the Royal Menagerie contained nearly three hundred creatures and sixty species. Not knowing how to feed or provide for such beasts, several of them died through poor treatment. The animals also attacked visitors and their keepers on occasions and, although stories vary, after one such attack, in 1830 the Duke of Wellington determined that the Menagerie should be closed. The animals were largely moved to the recently opened London Zoo.

Perhaps even more famous than its housing of the Royal Menagerie was the Tower’s use as a prison and site of execution, even up to and including the period of the World Wars, during which time several people were executed for espionage. William Wallace, Henry VI, James I of Scotland, Thomas More, Hugh Latimer, Thomas Cromwell, Thomas Cranmer, Catherine Howard, John Fisher, the future Queen Elizabeth I, Walter Raleigh, Guy Fawkes, William Penn, Samuel Pepys, Robert Walpole, Roger Casement, Rudolf Hess, the Kray twins, and countless other famous and infamous persons were held in the Tower at some point or other, far more illustrious company than virtually any other institution could boast. Lady Jane Grey and Anne Boleyn were among those both imprisoned and executed in the Tower.

The Tower also housed the Royal Mint for much of its history. The most famous Warden and later Master of the mint was Sir Isaac Newton. The position was originally given to the scientist as a sinecure, but he took the role extremely seriously, holding it for the final three decades of his life. He reformed the currency, improved minuting technology, and, to tackle the huge problem of counterfeiting, disguised himself to obtain evidence against counterfeiters in taverns and bars, cross-examining numerous witnesses, suspects, and informers personally.

We had planned to walk to Bloomsbury to meet up with a friend, but I received a message on social media from someone who was interested in meeting up while we were in the city. We changed our plans and went to King’s Cross, where we met up with him and had drinks in the nearby German Gymnasium, a building originally constructed for the German Gymnastics Society, which now houses a restaurant and bar. The roof of the building is a striking early example of the use of laminated timber for providing a large span.

After making our new friend’s acquaintance and having a great conversation, we went on to Bloomsbury, for a meal and drink with Sebastian Milbank. It was raining heavily by the time we needed to go back, so we ordered an Uber back to Shoreditch.

The next day, we had a relaxed morning. After breakfast in the Airbnb, Susannah and I took Oona out to a local café, where we had croissants. We had intended to visit the nearby city farm, but the weather was too inclement: Oona was not a fan of the winds. [Susannah: To be fair, it did turn out to be a proper named storm: Storm Benjamin. And the winds were so high it was in fact difficult to walk. But the croissant place had lots of games, which were a hit.] Back at the Airbnb, we played with Oona until her parents returned and then we went out to see some local stores.

I had only seen Oona once before, at the recent family reunion, and had barely had the opportunity to make her acquaintance, so it was wonderful to get to know her better over the period of their stay in Stoke and our time together in London. Early that afternoon, we took the train from Liverpool Street Station to Stansted Airport, from which we flew over to Marseille.

Networks, Shortcuts, and Hubs

I recently watched a video on Veritasium, a popular science YouTube channel, in which the host, Derek Muller, discussed some of the fascinating dynamics of networks and connections. The video itself is highly accessible, while covering an impressive amount of ground, so I recommend watching it.

Among other things, the video explores the ‘small-world’ phenomenon, the ways in which people who might seem to be extremely distant from each other, can frequently be connected through short paths. Muller considers how, were each person only connected to the hundred people closest to them, connections between people on the other side of the planet would take an extreme number of steps. However, the existence of ‘shortcuts’, people with connections outside of their ordinary clusters, causes the number of required steps to make such connections across the entire network to plummet, lowering the degree of separation between everyone, even those with few or no connections between their immediate contexts.

Remarkably, only a relatively small number of such shortcuts is needed to produce a ‘small-world’ effect comparable to what one might observe in a network with random connections across all its members. Yet, importantly, unlike a random network, such a network will also retain the highly clustered character of an ordered network. It really has the best (or sometimes the worst) of both worlds.

Later in the video, Muller turns to consider the phenomenon of the ‘hub’. Examples of hubs within networks are familiar from the Internet, which provide many of Muller’s illustrations of such dynamics—sites like Google, Twitter, or Facebook from and to which countless other sites are linked. Hubs are not mere ‘shortcuts’, regular network members with slightly more eccentric connections than their peers.

When networks are emerging, the connections that are formed are biased towards more their connected members, in part because they are more known (the dynamics here are related to the friendship paradox, the fact that most people’s friends have a greater average number of friends than they do). Such well-connected members attract others to them more than other members. As a network emerges and grows over time, such members of a network can become hubs. Recognizing the importance of hubs can radically increase one’s effectiveness in addressing certain group dynamics. Muller gives the example of Thailand’s attempts to control the spread of AIDS, and the way in which focusing on brothels as hubs proved markedly more effective than more general public health messaging.

Such dynamics can shed a surprising yet important light upon the Church. Michael B. Thompson has an essay in the Richard Bauckham-edited volume, The Gospel for All Christians, entitled “The Holy Internet: Communication Between Churches in the First Christian Generation.” Within it he explores the dissemination of information in the earliest Church. Thompson observes that, contrary to theories of isolated communities built around the varying messages of different apostles and early Church teachers, the first churches were bound together in a large network, within which messages travelled with regularity and relative speed.

While there were clearly defined clusters—local churches, most of whose members would be geographically rooted—there were also a lot of ‘shortcuts’ and some ‘hubs’ too. One would only need a few such shortcuts and hubs for the early Church to exhibit a pronounced ‘small-world’ character, while still having many distinct local clusters.

Thanks to the vast infrastructure of Roman roads and the sea lanes of commerce that joined places across the empire, it was possible for first century travellers to enjoy considerable mobility. There were also key hubs of communication for the early Church, places like Jerusalem, Rome, Ephesus, or Corinth. Christians in these and other localities would be expected to show hospitality to Christians from other parts of the world.

The epistle as a medium was bound up with such a network. While we tend to regard epistles merely as text, especially as we encounter them in our Bibles, imaginatively resituating them within their natural network of communication can reveal other purposes that the medium served. The sending—and later circulating—of an epistle created or strengthened connections between places and their respective communities.

For a fledgling movement, the ‘holy internet’ Thompson describes was a critical means by which the Church was built up. In the book of Acts, we repeatedly see this ‘internet’ in action. While we may be tempted to read the accounts of the apostles’ travel as if it were filler, it was a crucial part of the means by which the early Church was strengthened, encouraged, and made secure in the truth. Acts is, among other things, the story of the emergence of the church as a networked entity.

The ‘Holy Internet’ created bonds of mutual knowledge, concern, gift, support, and service between churches. It established churches as examples to each other. It connected the Church with its origins in apostolic testimony, ensuring that believers were rarely more than a couple of degrees of separation from multiple eyewitnesses of Christ’s ministry and resurrection. This network is one of the reasons why the apostles could boldly state that the work of Christ wasn’t something that occurred in a corner (Acts 26:26). News could travel quickly, especially in a closely networked set of communities such as those of the early church.

At the beginning and end of the various NT epistles, we can get a sense of this network too. As we want to get to the ideas, we can be inattentive to the way that the early Church was established, not merely through ideas, but through the constant circulation of apostles, evangelists, and various other servants of the Church, through gifts, messengers, travellers, letters, news, etc. For instance, even before Paul visited the city of Rome, he knew a great number of Christians already active there, people who would welcome his visit. The book of Romans isn’t merely a book of theological ideas: it is a book paving the way for a visit, a book appealing to and developing existing connections and anticipating the establishment of a greater future bond beyond Paul and the church at Rome. The hospitality of churches to strangers was part of how the ‘Holy Internet’ was made possible. There are various mentions in the epistles of Paul seeking a place to stay (Philemon 22), provisions, or praising Christians for their hospitality to others (1 Thessalonians 4:10).

The degree to which Paul’s apostolic teaching was bound up with an intense practice of networking can be seen in his extensive description of his movements and various practical missions in such places as the end of Romans. The relationship between Jews and Gentiles wasn’t merely a theological notion, but something to be worked out through such things as the contributions of the Christians of Macedonia and Achaia to the poor saints in Jerusalem: ‘For if the Gentiles have come to share in their spiritual blessings, they ought also to be of service to them in material blessings.’ The Jerusalem collection strengthened the ecclesiastical—and theological—web of connection between Jewish and Gentile churches, enabling Gentile Christians and churches in the wider empire to participate in the needs of the saints in Jerusalem.

The sending of epistles was also a way in which the form and the content of the apostolic message and ministry were closely related. Most of the epistles of the NT are addressed to the Christians in a particular city or to a specific person. Such epistles strengthened and built upon existing connections, ensuring that each church could be nourished by the ministry of others. They were a form of resistance to sectarian and isolationist tendencies, establishing unity through mutual sharing and ministry in a body. The epistles consistently remind their recipients of their place within a larger body of Christians. The recipients of the epistles are also frequently called to pass on the messages that they have received to others, or to ensure that a wider audience hears them (2 Corinthians 1:1; Galatians 1:2; Colossians 4:16; Romans 1:7; 1 Peter 1:1).

Over the last few years, as we have divided our time between Stoke-on-Trent and New York, and have travelled extensively in the US, the UK, and elsewhere, I have frequently reflected on the importance of ‘shortcuts’ and ‘hubs’ in the book of Acts (also upon the importance of the pilgrim feasts and the Levites as ways Israel was preserved from breaking apart into detached regional clusters). As we travel and connect with Christians in various places, we play a part in making the church a smaller world, often creating further connections as we bring people into contact with each other.

In our travels, we frequently have ‘small-world’ experiences (such as the one I described us having in Oxford above). We have been recognized on the streets—and in the bookstores!—of several cities and towns in the US, UK, and even elsewhere. We have come to love the serendipity that comes with putting ourselves in lots of situations where we are likely to meet new people, within which unpredictable new connections can arise. I have almost certainly met more than five hundred people in person whom I first knew online. Likewise, while we are not ‘hubs’, a lot of people initiate contact with us due to our connections (for instance, on account of Susannah’s work as a Plough editor) and we have small virtual communities around us.

Another analogy to which I often return is that of bridges and bridge-building, connecting places that might otherwise be divided or difficult to access from each other. Much of our lives is between worlds—between the US and the UK, between the academy and the Church, between various regions of the US, between different denominations, etc. A good bridge can enable fruitful and well-managed commerce between worlds, while also maintaining the distinctions between them. A bridge need not collapse worlds into each other, as some forms of networks are prone to do, but it can make possible worthwhile communication. Likewise, a good ‘bridge’ provides a well-defined point of contact and channel of exchange with other worlds, which lowers the sense of threat in the connection between worlds: the worlds remain distinct, while the points of contact and channels between them are provided by persons, agencies, and institutions who can be known and trusted. This contrasts with many of the ways in which groups can ‘connect’ with other worlds and outsiders online, which heighten conflict and polarization.

I firmly believe in the need for dense ‘clusters’ of local Christians—highly grounded and stable communities of Christians committed to and growing within specific places—and have often felt that modernity, in weakening clustering dynamics, can leave us poorer off in certain regards. There have been times when I wondered whether the more peripatetic character of my work was somewhat in tension with this conviction. However, over time I have come to appreciate that the Church has always required dense clustering and broad networking as complementary and counterbalancing forces. Were our way of life more widespread, it would not be good for the Church. Yet, if there were no people like us, the Church would also suffer.

Extreme travellers like the Apostle Paul in the book of Acts were quite unusual in their time, yet their travelling was immensely important for the development of the Church. Had everyone scattered after Pentecost to form local churches in various parts of the world, and travelling between churches not been a regular and enduring feature of the Church’s life, the Church would have become a very different entity, its catholicity and unity much less felt.

This is more of an introductory post, as the real meat of what I want to explore relating to networks lies elsewhere. I will probably post thoughts on those issues in our next Substack.

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ On the Mere Fidelity podcast, Derek and I had a two-person show on the Bible as a technology, and some of the ways that our thinking about Holy Scripture has changed with its developments. Derek, James, and I also discussed ‘reality respecters’ and evangelism.

❧ The Theopolis podcast series on Hebrews continues, with the following episodes: It is a Fearful Thing to Fall into the Hands of the Living God (Hebrews 10:17-33) and We Are Not of Those Who Shrink Back and Are Destroyed (Hebrews 10:34—11:3).

❧ I recorded my recent reflection on the doctrine of the Fall.

The Fall Without St Paul

Upcoming Events

❧ We are currently in Marseille in the South of France. Alastair will be preaching at a church in Marseille for the next two Sundays.

❧ Alastair will be speaking at L’Abri in Liss on November 21st. He will probably also be preaching that weekend in Salisbury.

❧ He will likely be preaching in Newcastle-under-Lyme—not -upon-Tyne—on November 28th.

❧ Next June, Alastair will probably be speaking in Oregon. He will then be visiting and speaking in Sydney and Perth in Australia.

❧ Much of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Alastair and Susannah

Thanks, this is cool! Also, please forgive the math below :)

I've been thinking about networks a bunch recently: there's a famous problem (the "degree-diameter problem") that asks "what's the largest network where any node in it has at most k neighbors, and any two nodes are at most d connections away?".

It's easy to find upper bounds: for example, if k=7 and d=2, a given node has at most 7 neighbors, and each such neighbor has at most 6 other neighbors, for a total of at most 1 + 7 + 7*6 = 50 nodes.

The above type of bound (the "Moore bound") is generally too optimistic: besides uninteresting examples (where k<3 or d<2), there are only two other known examples that attain the bound: a ten node network (where k=3 and d=2: it's called the "Petersen graph", very famous. There's a whole book on this little network!), and a 50 node network (where k=7 and d=2, called the "Hoffman-Singleton graph"). It's unknown if there are any other examples... but it is known that if there is another, it must have exactly 3250 nodes, each with 57 neighbors: figuring out if such a network exists or not is a somewhat famous open problem!

The 50 node network above is very symmetrical, with 252,000 symmetries (I helped my company design a t-shirt with this network on it, though it only displays 10 of those symmetries), and it can be used to construct a 100 node network with symmetries one of the 26 "sporadic groups". I recently came up with a model for the 50 node network, based on a dodecahedron ((basically) with the 30 edges, 12 faces, 5 inscribed cubes, and three added points, representing the 50 nodes, and some rules describing the connections). Networks are cool!