№ 50: Proclaiming Liberty

Biopolitics, the Episcopalianism of the US Navy, stillborn nationhood in Judges, and falling fertility rates

Alastair: Our last Substack post was published on our third wedding anniversary. In the evening, we went out for a celebratory meal at one of our favourite restaurants.

Knowing Susannah’s appreciation for tall ships, a few years ago I started keeping an eye out for tall ship news and events, especially ones that we might be in striking distance of us. Last year, for instance, we visited the replica sixteenth century Spanish galleon, the Andalucía, which passed under Tower Bridge in London.

I discovered that a tall ship, a sail training vessel for the Mexican navy and a sailing ambassador for the country, was going to be visiting New York—the ARM Cuauhtémoc. We wanted to visit it, but the weather was dull for most of the week, so we delayed our visit until the morning of the Thursday, May 15. While it was overcast, it was likely going to be the most clement weather during its stay.

The Cuauhtémoc was docked at Pier 17, near to Clipper City, the schooner that Susannah used to work on. With the Brooklyn Bridge behind it, it was an exhilarating sight.

The ship was primarily a working one and, while the deck was open for visitors free of charge at certain times, it was evident that it was not organized around this purpose. Indeed, the very process of getting on board required a leap over a large gap, from a raised platform onto the gangway.

The ship was a spectacle to behold from the pier, but seeing the pride and care the crew took in each of the fittings on board was inspiring. Susannah remarked at the time that, in all her years of sailing, she had never been so impressed by a vessel and its shipshape condition.

On the Saturday, we finally visited the Café Sabarsky, a Viennese café, which we had planned to visit for months. After her piece on Nicaea for our last Substack, Susannah was buzzing about the Church Fathers. Only a few minutes after arriving and ordering an einspänner, a Kaiserschmarrn, and a couple of other incredible delicacies, Susannah randomly remarked that she could not wait to go home and read Irenaeus!

That evening, I was working in my office when I heard that something had happened at the Brooklyn Bridge: a tall ship had crashed into it, destroying the top of its masts. It was with some horror that I discovered that it was the Cuauhtémoc. The cause of the accident was not immediately obvious. While many people had assumed that the ship tried to go under the bridge, not realizing that there was not sufficient clearance for its masts, this was obviously not what had happened. For some reason, the Cuauhtémoc had been stuck in reverse and, with only one tug, which was not tethered to it, and the pull of the retreating tide of the East River, had gone beneath the Brooklyn Bridge, its tall masts colliding with the bridge.

The next day after church the weather was glorious, so we decided to take a long walk. We wandered down the Empire State Trail from around Pier 46. While we had originally intended a shorter walk, after walking down the trail for some time we ended up deciding to walk further and walked over to Pier 17, where the Cuauhtémoc had been docked.

The Cuauhtémoc had been relocated after its collision with the bridge to Pier 36. It could be seen in the distance from its former berth in Pier 17. Curious, and as Susannah was hoping to write about it, we walked on, hoping to get closer to it and see the level of the damage firsthand. Having been so impressed by the ship when we saw it a few days earlier, it was heart-breaking to see the accident and even more terrible to hear that some of the crew had died and that others had been seriously injured.

We walked under the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges—neither of which I had walked to before—and round Pier 35. The way to the ship was blocked, but there was a gathering of media, photographers, and regular people before the place where the Cuauhtémoc was now docked. We ended up walking past Pier 36, getting a view of the ship from the other side too.

The next day was also a glorious one and, after several hours of work, we decided to walk up Riverside Park for an hour or two. Along the way, we encountered some adorable goslings, whose parents patiently indulged our photography for several minutes before giving us a gentle hiss to encourage us to move on. Fancying a pause, we came across Baylander, a former harbour utility craft and (extremely small!) helicopter landing trainer which had been converted into a floating restaurant and stopped for a drink, enjoying the breeze and views up and down the Hudson River.

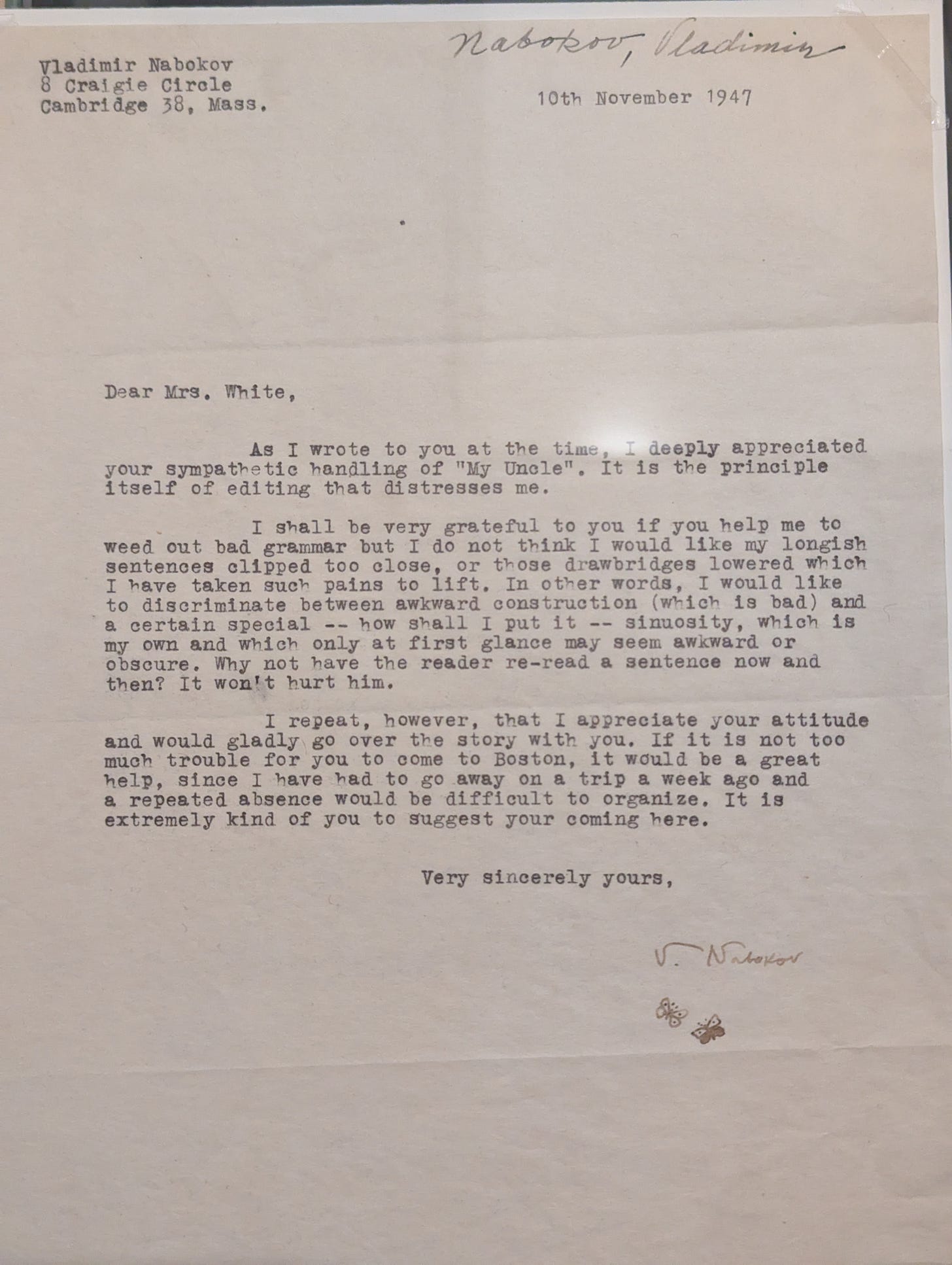

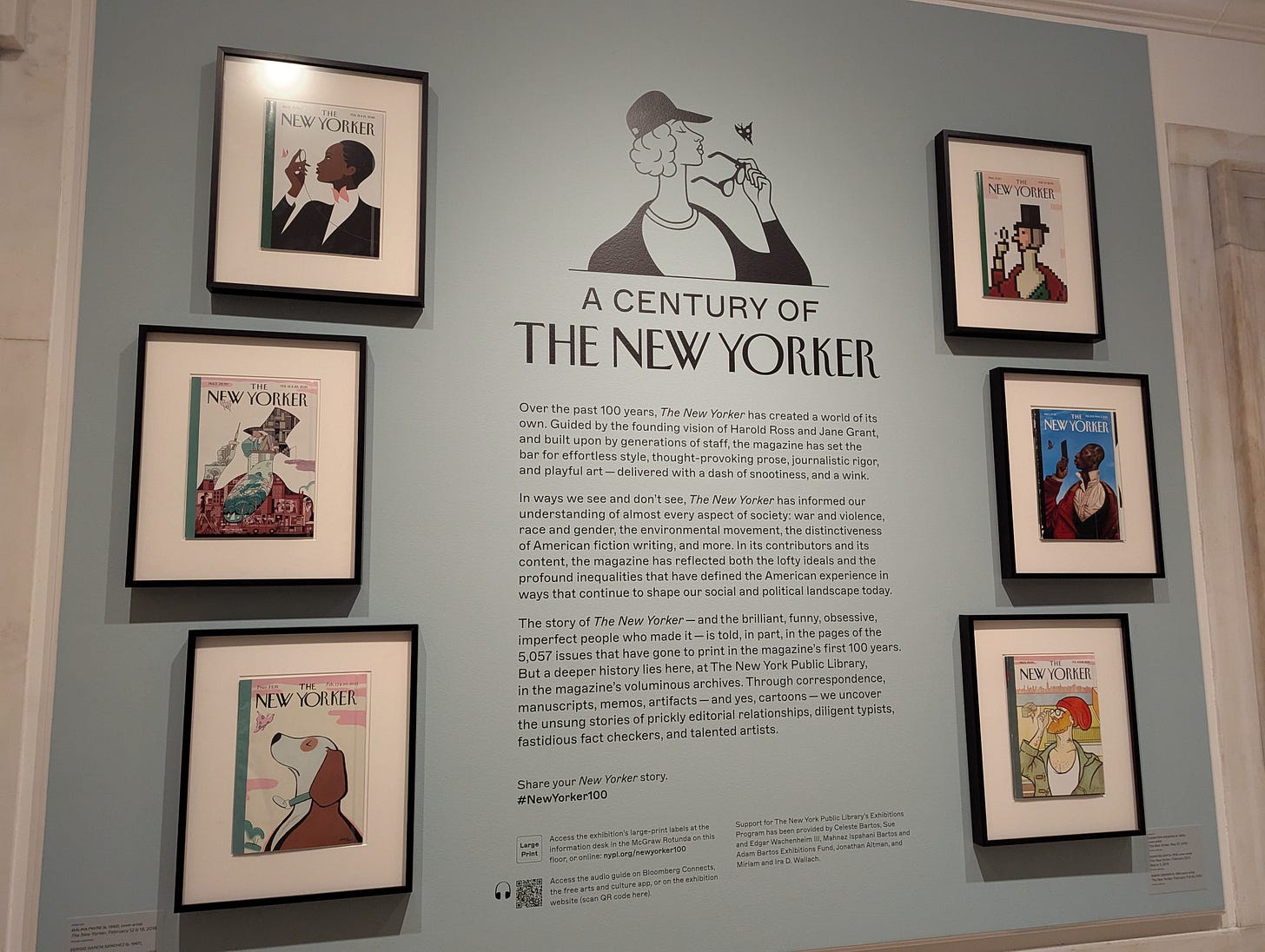

While he was in the city, our friend Dan Hitchens invited us to meet up, telling us that there was a New Yorker centenary exhibition in the New York Public Library. Besides the enjoyment of catching up with him, the chance to visit such an exhibition with two editors was too good a prospect to miss.

The Century of the New Yorker exhibition, which runs through February 21, 2026, was a delightful window onto the history of the magazine. It included several fascinating and amusing letters, a draft of Hannah Arendt’s “Eichmann in Jerusalem”, many iconic covers and cartoons from the magazine, and much besides.

A few weeks ago, I finally joined Radiopaper, a new social media platform, which seems to have a much higher calibre of conversation than Twitter. One of its exciting features is commissions, which enables users to offer other users some money, should they reply to a question or comment. Both Susannah and I have received commissions now and I am thinking of people whom I want to commission myself. Should you want either of us to answer a question upon which you would like to hear our thoughts, it is a very useful feature. One of the founders of the site is a near neighbour of ours and we enjoyed a pleasant visit to his family on the Wednesday evening.

A dear friend of Susannah’s suffered a very serious accident, cutting off his breathing tube, so she went to visit him in the hospital the following afternoon. I had bought tickets to the newly reopened Frick Collection a couple of weeks earlier, so I went around it with another friend of ours.

The Frick Collection was closed for around five years, during which time extensive restoration work had been done. It is an art museum, in the former mansion of the industrialist Henry Clay Frick, a large Beaux-Arts building. It is filled with stunning portraiture—Gainsborough, Rembrandt, Holbein, Hals, Romney, Whistler—and some other glorious works—Constable, Turner, Vermeer, Monet, Goya, El Greco—in sumptuously decorated rooms, with ceramics, medals, sculptures, and much else. My time was unfortunately limited as I had to teach a class, but it was one of the best art museums I had ever visited.

On Friday, Susannah left in the early morning for Plough meetings at the Bruderhof community in Fox Hill. I followed a few hours later, after finishing teaching my class. The Bruderhof community is situated in farmland near Walden in upstate New York. After working for a few hours in the Plough offices, we had a meal and meeting with the Plough staff. Every time I visit a Bruderhof community, I am impressed once again by their pattern of life, their thoughtful approach to their faith, and their openness to engaging with people beyond their community.

The next morning, we drove to New Paltz, where we would spend the next couple of days, gathering with Susannah’s family and having a memorial for her uncle Joel, who died in a tragic hiking accident several months ago.

We spent the first day enjoying time with the family and preparing for the event the next day. Susannah and I worked on the flowers, among other things.

The next day, we had a slower start to the morning, wandering along the old railway path from the place where we were staying, to the family house. The memorial was held in the afternoon, with many colleagues and friends of Joel in attendance. It was an incredibly moving event, especially hearing his siblings and family sharing their recollections for a remarkable man. I appreciated the opportunity to get to know several friends and relatives better over the course of the time. I was given a lift back to the city in the evening, but Susannah stayed on and travelled back the next day.

The next week was a very busy week of writing, as I had been unable to write over the weekend and had several articles to complete. It was also during this week that we released the first episode of Mere Fidelity, after our lengthy hiatus. I had been excited to share our new line-up. A few months ago, Derek and I wrote up a list of our top picks for potential cohosts. We were expecting to work some way down the list before getting the three new cohosts we hoped for, but our top three names all accepted our invitation. Although we could never replace our erstwhile lead host, Matt Lee Anderson, we are thoroughly enjoying our new iteration of the podcast.

On the Friday evening, we attended a superb event put on by our friend Bria Sandford, a panel discussion within which Lydia Dugdale, Ed Mechmann, and Kate Connolly discussed New York’s proposed Medical Aid in Dying Act (which has subsequently passed). Susannah moderated a panel discussion a few days later on the broader subject of euthanasia for Plough.

We had planned to visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art the next day, as there was an all-day event for the opening of the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing; we had also wanted to visit the Sargent and Paris exhibition. However, the queue was so lengthy that, after dropping by the Albertine bookstore, we decided to go to the Frick Collection instead, as Susannah had yet to visit it. She was astonished by the quality of the collection. Perhaps one of the things that most stands out to the visitor is the extent of the restoration work that has been done on the paintings. Indeed, if one did not know better, one could be fooled into thinking that they were painted within the past few years.

On the Sunday morning, some friends had invited us to attend Central Presbyterian, where N.T. Wright was preaching. We walked back from church through the park with one of our friends and, while Susannah went home, I went on for a walk with him along Riverside Park, seeing the goslings again, who are growing up quickly. After he left, some other friends joined us for ice cream.

Early Wednesday morning, Susannah and I flew out to Charlotte, NC, for a Davenant Faculty and Friends Retreat. We spent the afternoon helping to prepare for the arrival of the group, buying provisions and organizing everything in the larger of the two Airbnb properties we were sharing. Over the next day or so, we would spend time together, catching up and making plans for the year ahead.

Friday and Saturday were the Davenant Conference. Carl Trueman and Kevin De Young were the speakers, with Christian Freedom as the subject. Trueman’s first lecture on the Friday evening offered a material account of the rise of expressive individualism and the aesthetics of transgression, to complement the more intellectual accounts he has provided elsewhere. Kevin De Young’s addressed the Protestant understanding of the conscience and its importance in relation to liberty. We had the delight of seeing the wonderful Miles Smith and his new wife, neither of whom I had ever met in person. After the event, several of us gathered for drinks and further conversation at a nearby bar.

The next morning, Trueman delivered a fascinating paper on the development of Luther’s thought, especially upon the subject of freedom. Trueman’s lecture was followed by two periods of breakout sessions. I attended Michael Oppizzi’s brilliant talk on Augustine’s Confessions and C.S. Lewis’s Till We Have Faces and, in the second session, I gave a Pentecost-themed talk on the Holy Spirit and freedom. Susannah attended two different sessions, both of which she raved about: Matthew Stanley (‘When Freedom isn’t Liberating: Practicing Christian Freedom in a Post-Disciplinary Society’) and Miles Smith (‘The War of 1812 and the Protestant Civil War’). After lunch, the closing session was a question-and-answer period with De Young and Trueman. After helping to clear things away, Susannah and I hung out with Matthew Stanley for a few hours and then went to the airport.

We were both absolutely wiped out at this point. The social intensity and lack of sleep from the past week caught up with us, so we achieved little while waiting for our flight. The flight itself was full and, unfortunately, we were not assigned seats next to each other. However, shortly after we were both seated and waiting for the boarding to finish, we were startled by the familiar face of our dear friend Ben Miller! He was travelling back home from a camp in Tennessee to Long Island, with his wife and two of their children. While we could not sit next to each other, we caught up briefly after we landed in LaGuardia.

Sunday was Pentecost and we were pleased that we were able to be back in our church to celebrate it. However, the afternoon was a sad one, as Susannah’s mother’s dog, Lula, had to be put down. A rescue dog from Georgia, Lula was adopted by Susannah’s mother two and a half years ago.

In the evening, we joined Susannah’s dad and stepmother for a meal and a screening of the Tony Awards at the Players Club. There was a table quiz and, in a room full of artists and actors, Susannah was the only one to get perfect marks in a round of songs from musicals. I am so proud of her. As Susannah’s dad and stepmother were only in town for a short while, we met up with them again the next morning for breakfast at a diner. Later that evening, we went out for tapas with her mother.

On Tuesday, we met up with some new friends who were visiting New York with their family and talked theology. On the way back, we came across a band playing outside the Jewish Museum.

The month ahead is packed with travel and events. Check the ‘Upcoming Events’ at the bottom of this post to see some of the things that we have lined up!

Biopolitics and the Episcopalianism of the US Navy

Susannah: The two talks I went to at the Davenant event really could not have been more different, and they were both absolutely marvellous. The first, by Matthew Stanley, was very much a work in progress: he’s got Big Ideas about Foucault and biopolitics and the Shepherd vs. Weaver model of the political ruler, and cybernetics, and paternalism, and then there was another whole section about Ivan Illich and tools for conviviality, and I don’t know what else.

My main takeaway from it (I’m so boring about this, sorry, it will only get worse) was further reflection on the way that the tools offered by AI under the guise of giving us freedom (freedom to make a short film without hiring a filmmaker or learning all the various crafts of filmmaking, to make a piece of art in the style of Rembrandt without learning how to draw, etc) in fact restricts our freedom. If you don’t do the work of learning how to draw, you are not free to draw, however free you may be to type in a prompt to get an AI to generate an image for you. If you don’t have the attention span to read a whole book because your brain has been fried on these technologies, you are not free to read that book — just as much as if the book were banned. And the point of books is to jump from author to reader: no one writes for an AI audience, no one writes expecting or wanting to be summarized by a computer; that is not what writing and reading are for. They are for making both writer and reader bigger on the inside, Narnia or Tardis style.

We ended up getting coffee with Matthew afterwards and going down many many rabbit trails about this; he’s fascinating and fun, and I was so pleased to meet him. He also has a Substack.

Miles Smith’s talk could not have been more different. His was a historical paper about the distinctive religious culture of the US military—Army and Navy—from the Revolutionary War through the War of 1812. It was, he claimed, distinctively Northern —linked to the culture of the country above, say, the Ohio River, or the Mason-Dixon Line; Pennsylvania, New York and New England. That meant that it was distinctly not Evangelical, distinctly establishmentarian: Army and Navy chaplains were nearly all, though the end of this period, Episcopalian, and even the few Navy chaplains who were Presbyterian had to use the Book of Common Prayer for services.

The cultural differences extended to the enthusiasm with which the War of 1812 was prosecuted: in the Southern theater of war, the American troops fought the British with gusto, and their victories were much more decisive. Andrew Jackson of course made a name for himself in the South during the war, and he is, Miles claimed, emblematic of the new Southern populist evangelical American religious culture. They (as a very general rule) supported the French revolution, hated the British, were deeply suspicious of church hierarchy or hierarchy in society (besides racial hierarchy), and loved fighting.

Northerners simply were much less enthused about fighting at all. They had no beef with the British; yes, they’d broken away, but still thought of themselves as more or less cousins of Englishmen, and certainly had no desire whatsoever to aid the French.

I was extremely happy about this talk mainly because the history hit so closely on the Patrick O’Brien novels: “Oceans are now battlefields!” I kept saying to myself, and hopping around internally with joy. This being the culture of the Navy made total sense to me: even now, our Book of Common Prayer contains a section on “prayers to be used at sea,” and sailors are by habit not hyper-individualistic Pa Ingalls-style slightly cranky libertarian Scots-Irish border culture people, which you really need to be if you’re going to be an evangelical, or at least an American-style evangelical (British evangelicals are much more bourgeois in my experience). And of course American sailors were constantly getting impressed on to Royal Navy ships (and then getting repatriated) and so the culture of British naval Anglicanism would have seeped into the American navy inevitably. (The slogan of the American side of the War of 1812 was “free trade and sailors’ rights,” so it’s not like they LIKED being impressed, however.)

If both of these papers become books, they’ve got my commitment to preorder them, unless they’re published by some insane university press that charges $75 for a cheap print on demand perfect bound volume, in which case I will simply ask for a review copy.

The Freedom of the Spirit

Alastair: Sunday was the feast of Pentecost, so the timing of our Davenant Conference, on the subject of freedom, felt felicitous: the Spirit lies at the heart of the New Testament’s account of freedom. It is at Pentecost that we celebrate the pouring out of the Spirit upon the Church. For the Apostle Paul in 2 Corinthians 3:17, chief among the indicators of the presence of the Spirit of the Lord is the enjoyment of freedom—Now the Lord is the Spirit, and where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom. Within the context, what Paul regards as the content of this freedom is not directly stated. However, the hearer of the passage might reasonably suppose that Paul sees this freedom as including, yet not exhausted by, several dimensions of the Spirit’s work that are discussed or implied in the context.

In the broader context, Paul is discussing his ministry, and the confidence and boldness with which he exercises it. Paul’s confidence is granted by God and is experienced in the life-giving power of the ministry of the Spirit that constitutes new covenant ministry. On the Day of Pentecost, the Spirit descended upon the company, with fiery tongues appearing to alight upon each one of them. These fiery tongues were accompanied by the disciples’ declaration of the mighty works of God in multiple languages and preaching with boldness and incredible efficacy—the tongues of fire set their speech aflame, so that, speaking with new tongues, the fire of the Spirit might spread through their words.

“Is not my word like fire?” the Lord asks in Jeremiah 23:29. Prophets also bear fiery words. The prophetic witnesses of Revelation 11:5 are depicted as fire-breathing. In Jeremiah 5:14, the Lord declares that he will make his words in Jeremiah’s mouth like a fire. Isaiah’s lips are cleansed with a burning coal from the altar (Isaiah 6:6-7). Pentecost is a sort of prophetic anointing, empowering the apostles to speak authoritatively in the name of Jesus.

The freedom of the Spirit enjoyed by Peter and the apostles at Pentecost was the freedom of an authoritative commission, divine empowerment, and of a life-giving message. That the Spirit’s message is life-giving highlights a further dimension of the freedom he gives: he does not only embolden his messengers, but also liberates hearers from their bondage. In the chapter proceeding his statement concerning the Spirit, in 2 Corinthians 2:14-16, Paul marvels at his experience of evangelism, through which people are wonderfully delivered into new life—

But thanks be to God, who in Christ always leads us in triumphal procession, and through us spreads the fragrance of the knowledge of him everywhere. For we are the aroma of Christ to God among those who are being saved and among those who are perishing, to one a fragrance from death to death, to the other a fragrance from life to life. Who is sufficient for these things?

For Paul, the power of the Spirit contrasts with the weakness and mortality of the earthen vessels of his ministers of flesh. Like the heroes of old upon whom the Spirit came, enabling them to perform marvellous feats, the appearance of the Spirit’s power is the more remarkable for the frail and flawed instruments he employs.

The powerful working of the Spirit that Paul witnesses as he preaches the gospel and the clarity of his sense of the Spirit’s purpose disclosed in Christ fuels Paul’s assurance and confidence in situations that might otherwise provoke uncertainty or fear. Paul knows his apostolic commission, he knows the purpose of God in Christ, he is sure of God’s sovereignty in history, and he knows the power of the Spirit. This changes the calculus of action: a person so convinced walks by faith rather than by sight, acting in ways that confound those who live by faith. They can pursue impossible causes. They can take paths seemingly doomed to failure. They can face apparently insurmountable odds and resist the most threatening of opponents.

The gift of the Spirit introduced a radical new power into a situation that was lacking in it. It was neither a power wrested from political adversaries, nor one directly wielded against them. The advent of the Spirit propelled the Church into its mission, into a conquest of the nations through word and sacrament. The Spirit stirred up the spirits of the apostles, much as Cyrus and those who returned to rebuild Jerusalem and its temple in response to his proclamation (Ezra 1:1, 5). While the Spirit had empowered heroes like Samson and Gideon to fight against flesh and blood, the gift of the Spirit at Pentecost granted power for a mission that exceeded mere conflict with Rome and the opposing Jewish authorities. As Oliver O’Donovan claims concerning the power manifested in Jesus’ ministry:

Yet that new power was directed against the forces which most immediately hindered Israel from living effectively as a community in God’s service, the spiritual and natural weaknesses which drained its energies away. This was not an apolitical gesture, but a statement of true political priorities. Jesus’ departure from the zealot programme showed his more theological understanding of power, not his disinterest in it. The empowerment of Israel was more important than the disempowerment of Rome; for Rome disempowered would in itself by no means guarantee Israel empowered. The paradigm of the Exodus was, we might say, being read with an emphasis not on the conquest of the Egyptians but on the conquest of the sea. The power which God gave to Israel did not have to be taken from Egypt, or from Rome, first. The gift of power was not a zero-sum operation. God could generate new power by doing new things in Israel’s midst.

Elsewhere in the wider context of 2 Corinthians 3:17, Paul describes further dimensions of the freedom that the Spirit brings through the gospel. There is an aspect of negative freedom: the Spirit releases us from the old ministry of death that the Mosaic covenant represented. Paul speaks of this at length elsewhere, in places such as Romans 8:1-2—

There is therefore now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus. For the law of the Spirit of life has set you free in Christ Jesus from the law of sin and death.

The Mosaic covenant proved to be death-dealing, rather than life-giving. The law, Paul maintains, is spiritual, yet given to a fleshly people, it ended up condemning them rather than declaring them to be in right standing with God. The Spirit unites us with Christ, in whom there is no condemnation, on account of his death for us. Over against Paul’s characterization of the new covenant as one of reconciliation, the old covenant order appears as one of alienation: Israel’s alienation from God due to the judgment upon their rebellion against the covenant and the Gentiles’ alienation from God as those outside of the covenant and as strangers to God’s promise.

In 2 Corinthians 3, Paul discusses various further dimensions of the old covenant situation, which he terms ‘the ministry of death’ and ‘condemnation’. While given amidst the glory of the Sinai theophany, with Moses’s face shining with a reflected radiance, the old covenant was an order of less glory, of veiled glory, and of darkened understanding. As Moses covered his face when interacting with the Israelites and as the divine glory of the Most Holy Place in the tabernacle was hidden behind a veil, so a veil lay over the people’s understanding of the text of Holy Scripture. They received the words of Moses, yet the glorious sense of those words lay concealed. Besides deliverance from condemnation and from alienation, the new covenant entails deliverance from ignorance.

As Paul proceeds to describe the liberty from our past state of alienation and condemnation in Romans 8, he moves into a discussion of more positive freedom: the Spirit does not merely free us from a miserable condition, but frees us into a new form of life—

For God has done what the law, weakened by the flesh, could not do. By sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh and for sin, he condemned sin in the flesh, in order that the righteous requirement of the law might be fulfilled in us, who walk not according to the flesh but according to the Spirit. Romans 8:3-4

Besides being a harvest feast, Pentecost was associated with the gift of the Law at Sinai. At Sinai, Moses had ascended to God’s glorious presence on the mountain, receiving the Ten Words and delivering them to the people. However, the people had proven hard-hearted and rebellious, fashioning a golden calf. Three thousand of the children of Israel were killed by the Levites as a result.

Pentecost has several similarities. Happening on the feast day associated with the gift of the law, a prophet like Moses, Jesus Christ, ascended to God’s presence and gave the Spirit to the people. In contrast to Sinai, however, three thousand people were cut to the heart and converted through Peter’s message. While the gift of the Law proved death-dealing, the gift of the Spirit is life-giving. Yet the gift of the Spirit is not opposed to the gift of the Law. Indeed, the promise of the new covenant was that the Lord would write his Law upon the hearts of the people by his Spirit (Jeremiah 31:31-34), that he would give them a heart of flesh instead of their resistant hearts of stone, that he would place his Spirit within them so that they would obey his commandments (Ezekiel 36:25-27), and that he would circumcise their hearts (Deuteronomy 30:6). Pentecost is the new gift of the Law, the gift of the Law written upon the heart. It enables the freedom of law-keeping from the heart. Paul alludes to this in part when he writes of the Corinthians that they are a letter from Christ delivered by us, written not with ink but with the Spirit of the living God, not on tablets of stone but on tablets of human hearts (2 Corinthians 3:3).

Likewise, the promise was that the people would all know the Lord, from the least to the greatest, and that his Spirit would be poured out on all flesh. In Numbers 11:29, Moses declared ‘Would that all the Lord’s people were prophets, that the Lord would put his Spirit on them!’ Joel picked up Moses’ expression in his prophecy.

And it shall come to pass afterward, that I will pour out my Spirit on all flesh; your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, your old men shall dream dreams, and your young men shall see visions. Even on the male and female servants in those days I will pour out my Spirit. Joel 2:28-29

For Paul, the Spirit also frees us into the knowledge of God. The veil upon the glory of the words of Moses is removed and we have access to God with unveiled faces. Elsewhere, he speaks of the Spirit as the sign of mature sonship, removing Jews from their state of minority and the guardianship of the Law in the old covenant and Gentiles from the state of alienation and life under the stoicheia.

But when the fullness of time had come, God sent forth his Son, born of woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons. And because you are sons, God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, “Abba! Father!” So you are no longer a slave, but a son, and if a son, then an heir through God. Galatians 4:4-7

The Spirit grants freedom of membership and participation. The empowerment of the Spirit is not exclusive to the apostles, but each member of the body of Christ re-presents the one Gift of the Spirit in serving the body with their manifold and diverse spiritual gifts.

To each is given the manifestation of the Spirit for the common good. For to one is given through the Spirit the utterance of wisdom, and to another the utterance of knowledge according to the same Spirit, to another faith by the same Spirit, to another gifts of healing by the one Spirit, to another the working of miracles, to another prophecy, to another the ability to distinguish between spirits, to another various kinds of tongues, to another the interpretation of tongues. All these are empowered by one and the same Spirit, who apportions to each one individually as he wills. 1 Corinthians 12:7–11

As Paul writes in 1 Corinthians 12:13: For in one Spirit we were all baptized into one body—Jews or Greeks, slaves or free—and all were made to drink of one Spirit. Not only does this overcome the alienation or distance between God and man, but the alienation between man and man. The gift of the Spirit is the ‘blessing of Abraham’ (Galatians 3:13-14), by which the curse of Babel is overcome. The unification of proclamation in the multiplication of languages and the conduit between heaven and earth in the ascended Christ and the descending Spirit in Pentecost is God’s answer to the hubristic project of Babel.

The Spiritual ministry of the Church is one of freedom. Confident in divine providence, purpose, and power, it can confound the rulers of this present age. It is a ministry that gives life to the spiritually dead. It liberates people from immaturity and bondage and into the freedom of the children of God. Where once the law was an onerous burden, it is now freely and joyfully obeyed from the heart and with the understanding. A formerly forbidding and opposing authority now authorizes and empowers us. The Spirit grants us the freedom of access into God’s presence and dispels our darkness of mind, revealing the glory of Christ to us. He overcomes the divisions of mankind, bringing those once opposed to each other into fellowship. And he sets our lips ablaze, so that, with the apostles on the first Pentecost, we might declare these wonderful works of God.

Stillborn Nationhood

Alastair: The book of Judges has been one of my favourite books of Holy Scripture since childhood. In many respects, it is a scriptural house of horrors, filled with the most monstrous, extreme, bizarre, and unsettling images. It is also a remarkably rich and playful text, dense with internal literary links, through which the author explores profound themes. The best commentator I have read on the book is the late E.T.A. “Terry” Davidson, who brilliantly uncovers many of these elements in her Intricacy, Design, and Cunning in the Book of Judges (2008).

Recently, Peter Leithart, the head of the Theopolis Institute for which I work, has posted some random thoughts and notes from Davidson’s book. For instance, he mused on whether we are supposed to see ‘grotesque birth stories’ in the book, suggesting that the story of Ehud stabbing the corpulent King Eglon in his stomach, causing his guts to come out, resembled a ‘macabre Caesarian’ and that Jael is described as if she was nursing Sisera before she drives a tent peg through his skull.

At first glance, such a suggestion might seem strained: if we allow ourselves a certain latitude in our comparisons, just about anything can be related to anything else. However, Leithart is a skilled reader, with an instinct for the text that few others have; he can pick up on slight potential indicators of themes and, while they may sometimes be false trails, they often prove rewarding. Besides, when you are reading a book with as many strange and surreal images as Judges, strange symmetries between them might well be worthy of note (for instance, between Jael and Delilah, two women who betray a sleeping man by performing some action upon his head). That said, if you squint and turn your head sideways, lots of things can seem to look like other things.

There are several tests. You typically start with a possible connection, which is generally very weak. It is important to get a sense of how weak, for instance, by considering an array of other things with which you could connect it with that level of clarity. A real connection would need to stick out from other potential connections. Ideally, you want to see large and dense clusters of associations, specific and distinctive verbal parallels, structural paralleling of scenes, consistency of themes within a larger text, connections to another text that is frequently alluded to within the same book, and other such things.

Claims of connections are seldom open and closed. Nor do they rest upon a single line of connection; typically, there is a cluster of associations, from which a cumulative case can be formed. While it is easy to discount one or two possible connections, the more such connections multiply, the less plausible it is to deny them. Also, even if one were to argue against any one of the connections, as the weight of the case becomes distributed over several of them, the discounting of any one thread need not threaten the overarching connection.

A huge test is provided by other skilled readers, who will hopefully see the same thing, often quite independently. Skilled readers have an instinct for the texts of Holy Scripture and, being familiar with the ways that the texts operate, have a sense of what is within the bounds of likelihood within them. A good scriptural reading of this kind will also need to be fruitful. It is not enough to see neat literary plays; such literary artistry is almost invariably in service of insight.

Taking Leithart’s suggestion of Judges as a book with ‘grotesque birth stories’, I think a case can be made for there being a real and important connection here. Here are some other possible instances that came to mind:

1. In Judges 6, the Israelites hide their seed and produce in dens, caves, and, in the case of Gideon, a winepress, as the Midianites are spreading out over the land and devouring it. They frustrate the fruit-bearing of the land. The significance of containers—a pot with the meat of a young goat, a basket with unleavened cakes from an ephah of flour, and jars containing torches—being opened in the deliverance might recall the opening of the womb (especially when connected back to the story of Exodus). These, it seems to me, are connections that, by themselves, are not especially load-bearing but which, if others exist, might be quite illuminating.

2. In Judges 9, Abimelech, the son of Gideon, kills seventy of his brothers ‘on one stone’ (אֶ֣בֶן —Judges 9:5). In Exodus 1, seventy descended into Egypt with Jacob in the Exodus, and the baby boys were killed on the birthstool (אֹבֶן—Exodus 1:16). This seems like a stronger connection to me: Abimelech is like Pharaoh and there is a grim replaying of the Exodus, with the sons of Gideon being eliminated.

3. In Judges 11, Jephthah makes his rash vow that he will offer whatever comes from the doors of his house first as an ascension offering to the Lord. As several commentators have noted, the first through the doors of the house should be associated with the firstborn and the Exodus (the first to ‘open the womb’—e.g. Exodus 13:12). Jephthah hopes to dedicate his house and thereby secure the foundation of a royal dynasty, but tragically ends up sacrificing his daughter.

4. In Judges 13 we read of the annunciation of the birth of Samson, a Nazirite who is supposed to be the deliverer of the people. While not a grotesque birth story, although Samson is the deliverer announced from birth, he is far from the straightforward hero. He is a misbegotten Moses.

5. In Judges 14, the bees that come from the carcass of the dead lion are life in the body of another, a sort of bizarre pregnancy. The story of Samson is a cycle of stories that have a riddle-like connection to each other (and to those surrounding them, see, for instance, the references to 1,100 pieces of silver in both chapters 16 and 17). There are parallels, for instance, between the lion that comes roaring at Samson in 14:5 and the Philistines that come roaring at him in 15:14. There are also symmetries between the lion, symbolically overcome by the sweetness of the bees’ honey, and Samson, the mighty man overcome by the sweetness of (Philistine) women. Perhaps there is a further parallel to be drawn between the way the dead lion contains the bees and the way that a swarm of 3,000 Philistines were killed in the death of the lion-like Samson, after his great mane had regrown.

6. The concluding chapters of the book recall the story of the matriarch Rachel, from the book of Genesis. A parent unwittingly curses their child for stealing something from them, as Jacob unwittingly cursed Rachel on Laban’s behalf, the thief of her father’s teraphim (Judges 17:20; Genesis 31:19, 30-35). There is an abortive pursuit of the stolen teraphim (Judges 18:17-26). In Judges 19, the Levite’s father-in-law causes him to tarry at his house, even when he wants to depart, as Jacob’s father-in-law made him tarry. The Levite’s concubine is killed on the road from Bethlehem at Gibeah, near the place where Rachel died giving birth to Benjamin, on the road to Bethlehem in Genesis 35.

The grotesquely dismembered concubine recalls the matriarch Rachel. While his mother died, Benjamin was born in Genesis 35. However, the concluding chapters of Judges are about the near extinction of the tribe of Benjamin as a result of the enormity of the rape of the Levite’s concubine and the miscarriage (pun intended) of justice surrounding it.

Again, the connection between the death of the concubine in the doorway and the association of the doorway with themes of birth is important here. The similarities between the account of Gibeah in Judges 19 and that of the Sodomites in Genesis 19 is also important, as are the twisted Passover themes in both. The Passover, as we see in the law of the firstborn in Exodus 13, for instance, is a symbolic birth.

This might give some clue as to how a larger and more unified thematic point emerges from these various accounts. If Exodus is a birth narrative, with the birth themes of the opening chapters being recapitulated on the national level in the Passover and the passage through the Red Sea, Judges is a national miscarriage, a tragic and horrific failure of the people to achieve the birth of the kingdom. While a devourer like Eglon will be forced to disgorge his belly and Jael will play the destroying mother to an unwitting Sisera, themes of frustrated birth increasingly come upon Israel itself, its hopes of nationhood stillborn.

Falling Fertility Rates

My first Radiopaper commission (remember, if you have a question that you want to ask me, you can ask it over there and commission me to respond) was on the subject of the reason for the rapid fall of fertility rates around the world. The following is a slight expansion upon the thoughts that I gave over there.

We need to begin with a few orienting points.

First, fertility rates are falling almost everywhere, with few exceptions, so explanations for the trend need to be more global. Primary explanatory factors are likely not peculiar to Western culture.

Second, fertility rates vary markedly by country, as do the trend lines, even when they are moving downwards. For instance, South Korea, with the lowest fertility rate, has gone from around 6 to under 0.8 in the last 65 years. In the same period, the US has gone from around 3.65 to around 1.65. While the latter is a huge change, it is dwarfed by the former. Differences between trend lines, even when moving dramatically in the same direction, are worthy of attention.

Third, there are communities and countries that seem more resistant to the downward trend, even if they are decreasing. For instance, the Amish, while being in the US, continue to have fertility rates greatly above other Americans. Haredi Jews would be another example of a group retaining fertility rates far higher than others in their societies.

Fourth, the downward trend seems to have accelerated over the last fifteen years in particular, as Dr. Alice Evans argued in her recent conversation with Ross Douthat. This came out after the first version of my thoughts and her claim that connected devices are a critical part of the explanation makes sense to me, even though I am less persuaded by her accounts of the mechanisms by which they reduce fertility rates.

Why then are fertility rates falling? The following are several factors that come to mind. Not all these factors will be operative to the same degree in every context.

Reduced child mortality: When fewer children will be lost, people will not feel the same urge to have more.

Contraception: The normalization of contraception use is a huge factor. Having children becomes more of a choice, and one that tends to be delayed until many people feel that they have their ducks in a row. However, it might be that unexpected pregnancy is one of the best ways to push people to get their ducks in a row.

Delayed marriage and child-bearing: Fertility rapidly diminishes with age, so later marriage on a society level will mean fewer children.

Urbanization: Over the course of its near 250-year history, the American population has moved from around 95% to around 20% rural. Rural populations have higher rates of reproduction.

Child labour: I suspect that the effect of urbanization likely has something to do with the intergenerationality of much farming and the fact that children often work with their parents in farming. In traditional societies, where child labour is common, children are an economic asset, whereas they are much less likely to be so in industrial and post-industrial nations.

The decline of the productive family: Related to the above, when families are no longer the primary units of economic production in society, they have much less to pass on, and their relationships are more sentimental, weaker, and shorter-lived.

Increased and extended female education: This encourages the delay of marriage, meaning that fewer children will be born to women during their most fertile years.

Women entering a workforce outside of the domestic sphere in greater numbers: Such a workforce is less hospitable to children (or mothers). Childcare costs are prohibitive. And the added costs of transport, activities, and the like are considerable. However, much of the dignifying labour that might formerly have been possible for women in domestic realms, or realms connected to the domestic realm, are now alienated from it. Also, the degree to which women without careers created an extensive social fabric in neighbourhoods, a fabric that made it easier to have kids, is underestimated. The stay-at-home mothers of the past were not idle, but established a broad and hospitable realm for the raising of children, among other things.

Social expectations: Social tolerance for ‘free range children’ is low. Middle class parents are expected to prepare each of their children for college, with lots of activities, after-school clubs, etc. and to allow them to enjoy a host of costly amenities and consumer goods. Such costs cannot be sustained for many kids. A larger family requires a certain degree of benign neglect in parenting, a high-trust society, eyes on the street, older children helping to raise younger children, and much else. Those norms do not really exist nowadays. A woman with three or more children will be subject to social judgments in many contexts, as will a woman who focuses on her family over her career.

Loss of extended family: Families are smaller and more nuclear, meaning that the burden of care falls more narrowly upon one parent. When grandparents, relatives, and other parents were in the mix and there were gangs of siblings, cousins, and trusted friends much less parental supervision and involvement was needed.

The car: A society built around cars tends to be dangerous for and inhospitable for children. Transporting a large family legally in a society where you need a car to get by is very costly.

The loss of tight-knit, stable, bounded, intergenerational, and relatively homogeneous communities with strong shared customs, beliefs, and values: Such communities secure fairly enduring common lifeworlds, within which elders have a lot more agency in directing the lives of younger people, where departure from the social norm is much more penalized, where there are high and costly thresholds for rejecting the social structures and norms, and high bars for both entry and departure. In such communities there are many inducements and pressures to invest in a common social order and institutions and penalties if you do not or if you betray them. The society is geared to protect and encourage the building of common social capital. Families, homes, churches, and neighbourhoods are such social capital. When there is ease of entry and exit into marriage, for instance, investing much of your life into creating a family and a home is a much higher risk.

The normalization of divorce, not marrying at all, and increased distrust, competition, and antagonism between the sexes: This follows on from the previous point. Having children requires putting weight on one’s relationship with the other sex and, where social norms and stigmas do not secure that relationship, where there are high levels of distrust and antagonism between the sexes, where there is not a reinforcing network of secure and positive bonds between the sexes, and where the dissolution of such relationships is commonplace, placing such weight is a risk.

Secularization: Religions typically celebrate children, encourage their adherents to have more of them, and create social structures and instil patterns of practice that support child-rearing. Religions also tend to encourage filial piety and sacrifice for others, strengthening an intergenerational bond that is typically integral to higher fertility rate societies.

An existential shift in perception: Where mortality is low, society and its institutions are weak and rapidly changing, old familial structures no longer dominate society, dominant life narratives involves leaving home and forging one’s own destiny, filial piety plays a minor role in people’s lives, and religion is much weaker, people experience their lives differently. The intergenerational horizon of existence that encourages people to create a wider family, an intergenerational legacy, to honour the sacrifices of those before them, and to make sacrifices of their own for generations yet to be born no longer is powerful. People’s existential horizon is saturated with more private career goals, immediate pleasures, and consumer goods.

Connected devices and social media: Couples are increasingly connecting using social media and the Internet, but connecting online does not naturally encourage the same pairing off dynamic that one has in smaller groups. Pornography use renders young men less suited for and less propelled towards marriage and creates tensions between the sexes. Social media increases the power of many social influences, likely including a number of those depressing fertility rates. While marrying and having children might have heightened women’s social status in many societies, social media tends to privilege young and unattached women, while rendering those with children less visible. The collapse of formerly more distinct male and female social spaces into each other has also produced growing polarization of the sexes.

Health and environmental factors: The prevalence of obesity worldwide has more than doubled since 1990. Obesity has a significant impact on reproductive health. Microplastics also seem to affect reproductive health. There have been concerning, though disputed, claims about radically decreasing sperm counts, which some scientists have attributed to microplastics.

Official measures: China’s former one child policy would be an example of this.

Many other things could be mentioned, but these are clearly interrelated factors driving the trend. The groups that resist the trends tend to be highly religious, communal rather than individualistic, and form tight-knit ‘villages’ to bear the burdens of child-rearing. Being in a homogeneous and high trust society, stable in one’s forms of life, less connected to social media, with older people and the wider community having a lot of power and influence, and with a lot of responsibility placed upon older children might all provide contexts conducive to larger families.

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ After our length hiatus, Mere Fidelity is back! We are now joined by three new cohosts: James Wood, Brad East, and Joseph Minich. We have also rejoined the Mere Orthodoxy fold, as their flagship podcast. Our first episode is a classic Mere Fidelity controversy, with James, Derek, Brad, and I discussing how we ought to think about Pope Leo XIV. Our second episode, with Derek, Brad, and me, is on the subject of vocation. Joseph Minich’s inaugural episode was our third, on the Jesus People: The Counterculture that Became the Culture.

❧ The Theopolis podcast series on Hebrews continues, with the following episodes: The Certainty of God’s Promise (Hebrews 6:9-20), The Priestly Order of Melchizedek (Hebrews 7:1-10), Jesus, Priest After the Order of Melchizedek (Hebrews 7:11-17), and A Priest Exalted Above the Heavens (Hebrews 7:15-28).

❧ I have started recording another series for the God’s Story Podcast, but my series on Zechariah has now been completed, with episodes on chapter 13 and chapter 14.

❧ I wrote a piece on AI and our relationship with words for Christianity Today.

If we look for our human uniqueness in our capacity to produce textual artifacts, AI poses an existential threat. Not only does it show the difficulty of distinguishing the products of machines from those of human beings; it also reveals just how mindless and machine-like much human speech and writing can be, especially in a bureaucratic society.

Yet there is another way of regarding our relationship to language, a relationship more apparent in a society before the dominance of the written and printed word. In an oral culture, words are encountered not in autonomous texts but in speakers, ceremonies, and performances—in poets and singers, liturgies and plays, storytellers and orators, priests and public readers, politicians and philosophers. The primary vehicle of the word is the person.

Read the whole thing here.

❧ My Theopolis series on time continues.

The Sabbath and Time-Keeping

Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy and Time

James Jordan, Time, and Maturity

History is Going Somewhere

❧ I have produced a video of a past Argosy reflection.

Teaching as Feeding

Upcoming Events

❧ Much of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

❧ Alastair will be helping to lead the Protestantism and the Commonwealth residential course for Davenant next week. It might still be open for last minute registrations.

❧ This year’s Theopolis Ministry Conference is entitled ‘Singing the City of God’ and is on the subject of music in the life of the Church. You can find out more about it here.

❧ Alastair will be leading an online workshop for Theopolis in October and November on the subject of Pentecost. It is only $150 for ten hours of classes.

❧ At the end of September and beginning of October, Alastair will have events in Langley, BC, in Columbia, SC, in Birmingham, AL, and in Franklin, TN. Watch this space!

Much love,

Alastair and Susannah

Speaking as a sailor, I'd say that we are definitely more like hyper-individualistic Pa Ingalls-style extremely cranky libertarian Scots-Irish border culture people. No "slightly" about it.

But seriously, American naval and merchant marine culture is definitely more suffused with Yankee customs and habits of mind than other American vocational subcultures are, due to where our technology and training were bred. There's a reason that there are four merchant marine academies in New England, and only one on the west coast and one on the Gulf coast.

I've long wondered how correct the popular characterization of Scots Irish border people as irredeemably contentious and divisive really is. It certainly seems true if one drives through the country side of east Tennessee, observing 10 different little country churches, each standing 500 yards down the farm road from one another; a "Primitive Baptist" church here, a "Hardshell Baptist" church there, a "Free Will Baptist" church there, reminding one of Freud's narcissism of small differences. One shudders to think of the breakups which precipitated each new building.

Yet, the US founding, with its many Yankee agitators, had its share of contentiousness. Straight up Englishmen had been bred for hundreds of years for regicide, revolt, and combat. The rebellion, or "revolution" as we labeled it, was almost inevitable. Some ornery Virginia blood helped it along, but the Yankees more than did their part.

Given where it's all gone, I certainly feel Mather heavily on some recent days... "What's better, to be ruled by one tyrant three thousand miles away, or three thousand tyrants one mile away?"

My theory is that Scots Irish border people contumacy wasn't inevitably ingrained, but rather malignantized by the plantation geography which made man-stealing so much more of a temptation to them than to the Yankees. Not geographical determinism per se, but rather what to the unaided eye would seem an unhappy accident. But really, perhaps, a test of faith. "You say you have mastered the Bible over and above your brethren, you Presbyterians?" says the Lord. "Fine. Do you know the Law? Will you free your captives?" and sadly they failed, and to this day haven't quite recovered.

Thanks for this! I will look at Radiopaper though I suspect I need a one-in-one-out policy when it comes to social media platforms...

The fertility rate question is very interesting. My friends who have large families are all trad Catholics with traditional family setups, where the wife doesn't work and they are generally making an effort to buck the trend and being necessarily less consumerist etc. My secular friends are all either childless or have one or (at most) two children, and more gadgets.

What interests me is the communal element. The Amish and the Bruderhof seem wonderful to me but typical attempts to form "villages" in intentional ways seem fraught with problems. My wife grew up in a Catholic communal set-up where various families lived together, and it was not healthy at all. Places where lots of Catholic families congregate around e.g. a church with a regular Latin Mass seem to breed social hierarchies and pecking orders which are quite repellant to some of us.

I wonder if it's one of those things where you have to sort of aim off if you want to hit the target. We live in a 1960s housing estate, in a little terrace overlooking a green, and our children are able to play out on the green with the other children who live in our road under the vague supervision of the other parents, and that's a fine thing. But by doing that we are just piggy-backing on the habits and instincts of our working-class neighbours; the other middle-class couple on our road keep their one child inside when the other children are playing because the typical British middle class family is very private. This isn't an arrangement we have sought out, but it has sort of grown up around us serendipitously (and it's not without its downsides). Obviously it would be lovely if the other parents were all just like us, and the children were playing at being knights rather than superheroes while the parents discussed The Anchored Argosy with each other when not praying the rosary, but if we were to aim directly at making that happen I suspect it would quickly go a bit bad.