The Extremely Not Secret History of the Council of Nicaea

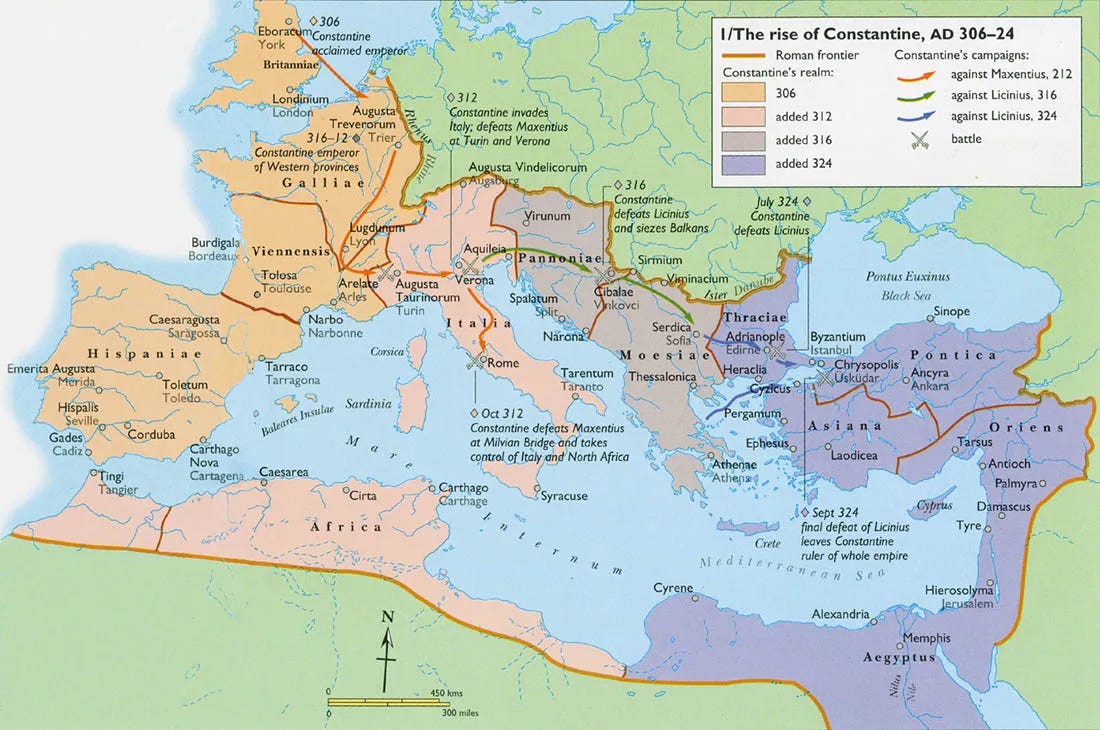

Susannah: This year, and this month of this year, mark 1700 years since the Council of Nicaea. On May 20, 325 AD, the Emperor Constantine opened the Council with an address to the 318 bishops assembled. He was not a bishop and thus not a voting member of the council, but it was he who had urged the bishops to come together to sort through what was becoming an urgent problem in his empire.

He was 53 years old and had been on the throne for 19 years at this point, having been crowned—oddly—in the English city of York, 1600 miles from his birthplace in what is now Serbia. The Empire still stretched that far North and West, though it would not do so for much longer. The council itself was held closer to the empire’s heartland: Nicaea is now called Iznik, in Turkey, and, five years afterwards, Constantine would move the capital from Rome—which was feeling shabby and depopulated—to a city on the Bosporus Strait, the divide between Europe and Asia. He called that city New Rome; we call it Istanbul. For the 1600 years between its founding and 1930, it was called after him: Constantinople.

Nicaea is 90 miles southeast of Constantinople, with its own imperial palace and a church designed in imitation of Constantinople’s Hagia Sophia, the Church of the Holy Wisdom; it was in this palace and church that the bishops met. Constantine paid for their travel and lodging; twelve years before, in the Edict of Milan, he had legalized the practice of Christianity and brought these men out of the catacombs and hidden places.

It hadn’t been all catacombs and lions: persecutions had waxed and waned. But the final persecution before the Edict had been the bloodiest, the most vigorous: it had been kicked off in 303 AD by the Emperor Diocletian, and lasted for a decade. Nearly everyone at the council was a veteran of the persecutions to one degree or another: the edicts had come down one after the other that all subjects of the Emperor were to offer sacrifice to the traditional Roman gods or face death, torture, or exile. Bishops and presbyters and deacons had been ordered to hand over all copies of the scriptures; many had done so; many had not.

What to do about those “traditores,” handers-over, who had during the persecution given up the sacred books to Diocletian’s soldiers, or who had otherwise betrayed their brothers and their calling as Christians, was a major problem: there was a party of hard-liners who held that such men could not be received back into the church. It had already been decided before the Council that the Gospel was such that even these traditores could be received back into the Church if, like St. Peter after his triple denial of Christ, they repented; Donatism, named for Donatus who was a leader of the hard-line party, had been repudiated. The dozen years since the ending of the persecutions had been a time of rapid growth and, as one might say, embourgeoisement of the church: now, you could be a Christian and also a full member of Roman society; you could study philosophy in Athens or read law in Rome and go to church openly every Sunday.

The history of the church up until this point was quite public; we know in detail what they had been up to: celebrating the Eucharist and listening to the reading of the Hebrew Bible and the collection of writings universally agreed on to be of apostolic origin which are the New Testament. We know about their conversations and their disagreements and their dramas and their comedies.

The last of the apostles had died as long before the Council of Nicaea as the American Revolutionary War is before us. The canon was as clear and universally accepted as, say, the Federalist Papers and the Constitution and Declaration are with us; the institutional continuity of bishop to bishop as traceable as our line of presidents or supreme court justices. There is nothing shadowy about the Church up to this point, illegal as it had been. One standard English translation collects the writings of the Ante-Nicene Fathers in nine volumes of more than 10 million words total, with letters, sermons, liturgies, histories, catechisms, theology, and commentaries all represented. And that’s just the formal documents we have. And not even all of them!

But recently a new set of teachings had come in. These teachings, associated with Arius, a presbyter/priest properly ordained in the universal, or catholic, church, had been kicking around since the 260s or so, but they had begun to grow in popularity beginning by 318. Briefly, the beliefs were neoplatonist: there was a single unknowable high God, who had created all things; Jesus was one of the things he had created, an “emanation” of him. This idea, which was largely an attempt to rationalize the much more mysterious idea of the Trinity (the word was beginning to be in use by this point; the idea was as old as the church itself), was appealing precisely because it was more rationalist, making a version of Christianity that would be acceptable to the science of the Greek philosophers. It sidestepped the scandal of the Incarnation—in the Arian system, it was not God who was made man, but one of his creations.

The Trinitarianism that this new teaching sought to supplant was a matter of a series of assertions and negations, a sort of list of realities, truths, witnessed to in Scripture and taught by bishops in a line back to the apostles. That list went something like this:

There is only one God: the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, Who made Heaven and Earth.

Jesus is God.

God, the Father, begot Jesus, his Son; they are not the same person, but interact both with us and with each other.

The Holy Spirit, the Spirit of God, is also distinct; “Father, Son and Holy Spirit” are rightly spoken of in a triplet phrase that sets them in parallel to each other.

We worship all three of these as God.

We do not give divine worship, we do not offer sacrifice, to any who is not God.

Remember, there is only one God.

This was the “faith once delivered to the saints.” In this, St. Paul had written to the Thessalonians, they were to “stand firm and hold to the traditions that you were taught by us, either by our spoken word or by our letter.”

What there was not was a set of philosophical terms that could try to make sense of this. And there was a certain hesitation among the bishops—there always had been—about introducing such terms; it was so easy to go wrong. Homoousios, “same nature,” was a term that some theologians had been experimenting with; others, though they held to the same list of realities, the same data points, were nervous about it, because it seemed somehow too precise, at risk of going beyond the tradition.

But then another set of teachers came along, and they didn’t just deny the term: they denied a couple of the data points as well. It was all very simple. There was only one God. Jesus was a creation of the unknowable Father; though his first and highest creation, far higher originally than a mere human, still, he did not share God’s nature, his God-ness. He was homoiousios: of a similar nature. He resembled God.

This rationalized and yet trippy version of theology was getting very popular, especially among the army. And most of the bishops were having none of it. No, they said, you couldn’t be a priest and talk this way. No, you cannot be baptized into the catholic church if this is what you assert. Finally, Arius, a priest under the bishop of Alexandria in Egypt—helpfully called Alexander—was a bit too loud and insistent in his discussion of these doctrines, and Alexander set up a debate, in which he articulated the apostolic doctrine once again. Arius declined to agree, continuing to teach his jingle: “There was a time when the Son was not” (apparently it’s very catchy in Greek.) Alexander was not one of the early church’s great theologians; he was simply a bishop who had been taught what the Apostles taught. And surely—he had been very fond of Arius—surely Arius was not saying that the Logos, the Word of God, had come into being at some point in the past? Surely he was not saying that our Lord Jesus was a creature, was not to be worshiped as the God of Abraham? That is not how Christians talked, that is simply not the faith of the fathers.

But Arius was saying that. Once Alexander fully understood this, he commanded Arius to leave aside these novel teachings.

Arius refused to do so. And so did four of his fellow presbyters in the diocese of Alexandria, and so did five deacons. We know their names. We know all of this. None of this happened in a corner.

Alexander, in grief, excommunicated Arius.

And that’s when the Emperor heard of it. His calling of the council of Nicaea was the act of an exasperated man: these Christians had seemed, when he legalized their faith twelve years earlier, to be a wonderful source of unity and strength. And now they were quibbling about words. Was it for this that he had left behind the old gods? Roman paganism had at least been more relaxed than this. So, at his summons, Arius and Alexander and as many other bishops and priests who could make it showed up at Nicaea, in that Spring of 325.

Bishops came from across the known world, from every country where Christianity had spread. Eusebius Pamphilius mentions

Cilicians, Phœnicians, Arabs and Palestinians, and in addition to these, Egyptians, Thebans, Libyans, and those who came from Mesopotamia. At this synod a Persian bishop was also present, neither was the Scythian absent from this assemblage. Pontus also and Galatia, Pamphylia, Cappadocia, Asia and Phrygia, supplied those who were most distinguished among them. Besides, there met there Thracians and Macedonians, Achaians and Epirots, and even those who dwelt still further away than these, and the most celebrated of the Spaniards himself took his seat among the rest.

Persia and Scythia were both, notably, outside the Roman Empire; though it had been initiated by Constantine, it was not a meeting of or for politicians of the Roman Empire, but clergy of the Christian church. Constantine gave opening remarks, but had no vote, and did not preside. That job was taken by “the most celebrated of the Spaniards himself,” Hosius, the Bishop of Cordoba, who was close to both Constantine and to Sylvester, the primus inter pares Bishop of Rome. Hosius’ signature, as president, was first on the list of signatories to the doctrinal formula ultimately affirmed at Nicaea. Vincent and Victor, two presbyters, came afterwards, writing before their signatures that they signed “for the venerable man, our holy Pope and bishop, Sylvester… believing as written above.” (Sylvester himself was too old to travel.)

Also present was Nicholas, the bishop of Myra, a town on the Turkish Mediterranean coast 400 miles from Nicaea; he, like many there, had been caught up in Diocletian’s persecution, had refused to turn over the holy books or sacrifice to the gods of the Empire. He was just the same age as Constantine, 53, but would long outlive him. It is sadly probably not true that he slapped Arius in the face during the course of the proceedings, but that does not stop people from resurrecting the rumor of Santa Claus smacking Arius and getting briefly jailed by Constantine for it every December 6th.

But the person who emerged as a startling force during the council was a young man, probably twenty-nine at the time, Alexander of Alexandria’s secretary, a short redhead with dark skin called Athanasius.

There is a popular version of this story. The popular version goes like this: up until Constantine, the Christian church was a series of independent congregations following the path of the Carpenter from Nazareth, with varied beliefs about who and what he was; there was no canon law, no structure, no church hierarchy; mostly they didn’t think about theology. Then Constantine noticed the religion and decided that with some tweaking it could be made to be the spiritual substructure of a renewed centralized empire, and it was he who invented the idea of Jesus as an imperial God; he who established the list of books of the Canon, he who insisted on a defined creed and a hierarchical church government. This is the story that Dan Brown tells in The Da Vinci Code; it is a story that many spiritual-but-not-religious folk and (with some variation) some fundamentalist low church protestants share (of course the fundamentalists for some reason nevertheless accept the divinity of Christ.)

There is a harder core version of this story, which was put forth in an organized way a generation later, in an essay published in the year 363. In that story, Jesus, a simple holy man from Nazareth, had had his message of universal peace corrupted by the nefarious Paul, and then by John, who wrote Christ’s divinity into the gospel that bore his name. The true, simple, ethical message of the man Jesus was, in this story, lost almost immediately after the crucifixion.

The person who wrote the essay had been raised a Christian. He had studied the pagan philosophers in Athens under the Neoplatonist rhetoricians Himerius (a pagan who would later become an initiate of Mithras) and Prohaeresius (a Christian). His two best friends at this point were fellow students who were, like him, Christians from Cappadocia: Basil and Gregory.

They were part of the first thoroughly post-persecution generation; one of Basil’s maternal grandparents had been martyred under Diocletian; his paternal grandmother, Macrina, and her husband had been exiled; but that was a long time ago. As Christians studying with pagan and Christian professors and alongside pagan friends and fellow-students at the heart of the philosophical world, the three young men had taken part in many symposia, many late-night debates. Gregory wrote movingly about their time there, many years later when he was preaching at Basil’s funeral:

We were sent by God and by a generous craving for culture, to Athens the home of letters. Athens, which has been to me, if to anyone, a city truly of gold, and the patroness of all that is good. For it brought me to know Basil more perfectly…

Basil went on to become Bishop of Caesarea; we call him St. Basil the Great. Gregory went on to become Bishop of Nazianzus and then later Archbishop of Constantinople; he is called Gregory Nazianzen.

Their friend Flavius Claudius Julianus was Constantine’s nephew. His essay was titled Κατὰ Γαλιλαίων, Against the Galileians, and it was, it goes without saying, fabricated whole cloth. He wrote it during the two years after he was acclaimed Emperor and before his death at age 31; it was part of his larger project to return the Empire to the worship of the old gods. Not many years after those late-night Athenian debates with Gregory and Basil, he had had himself rebaptized in the blood of bulls, in order to nullify his Christian baptism. We call him Julian the Apostate.

The story of these times, of the First Council of Nicaea and of its aftermath, is not just not what, for example, Dan Brown claimed: it’s literally the opposite. First of all, the issue of the Canon of Scripture never came up at the Council; second of all, Constantine didn’t interfere at the council on behalf of what is now orthodoxy. If anything he was sympathetic to Arianism, but mainly he was against a creed that would exclude the Arians: he wanted everyone to stop fussing.

He was complicated, but probably at least at this point in his life one thing he wanted was a Christianity that was a popular religion to tie together the empire and provide continuity with paganism. He would also have been happy if somehow that religion brought in the popular military cult of Sol Invictus, the Unvanquished Sun. He wanted minimal theology, because minimal theology means that bishops aren’t excommunicating priests and fighting with each other over vowels. He wanted a sort of syncretistic/neoplatonist vibes-based and yet unifying religion that he had control over.

That is what he didn’t get.

It’s not that he didn’t try to interfere theologically. He tried, though not at the council itself. At one point after the council, he commanded Athanasius, who had been Alexander’s secretary and who was now himself Bishop of Alexandria, to rescind Alexander’s anathematization of Arius.

“If a decision was made by the bishops,” Athanasius responded,

what concern had the emperor with it? . . . When did a decision of the Church receive its authority from the emperor? Or rather, when was his decree even recognized? There have been many councils in times past, and many decrees made by the Church; but never did the fathers seek the consent of the emperor for them, nor did the emperor busy himself in the affairs of the Church. . . . The Apostle Paul had friends among those who belonged to the household of Caesar, and in the writing to the Philippians he sent greetings from them: but never did he take them as associates in his judgments.

In other words, Constantine was, for at least part of his life, really trying to be in a Dan Brown novel. Like, his level best. Not the part about deciding what books were in the Bible, but the part about patching together an imperially helpful compromise syncretistic religion.

That religion would have been Arianism: a platonic high God with a Jesus who was a sort of highest in the created order Sol Invictus divine son. Who one was allowed to worship.

This religion would have been amenable to all kinds of both gnostic and demi-pagan developments: you could bolt on an emanation or two; old gods could sneak back in as Arian “saints” to be worshiped. Because if you could worship a created being in Jesus, why not worship other lesser created beings? As a treat?

But that is precisely what was rejected, as a bizarre innovation, at and after Nicaea. One God. Christ Jesus, the man, is God. Consubstantial with the Father. There was no time when He was not, even if it’s catchy to say that in Greek.

All the saints who we honor, Mary herself, are simply not consubstantial with the Father. They’re not God. That is not and has never been orthodoxy. And this has always been entirely public and clear.

The possibility of a paganized and syncretized religion presented itself, then: as long after the death of the last apostle as we are after the American Revolutionary War. It tried its best. It looked very much like it was going to win. Not at the Council - all but two of the 318 bishops who attended the council rejected Arianism. But tremendous pressure was put on Athanasius after the council, by Constantine and his son Constantius, to renege and declare that it was fine to regard Jesus as other than the God of Abraham. It was mostly a matter of propaganda: the council had spoken, after all. And Athanasius had no particular authority other than as a bishop. But he was the public face of Trinitarianism, of the stubborn catholic position. He was banished, and brought back, and banished again; at one point, Julian melted down at him, and in one last decree of banishment said that he was “a contemptible little fellow, unfit to be a leader, hardly a man at all, only a little manlet.” This was the time of Athanasius contra mundum.

The new religion, the Arian religion, this Christian-flavored semi-Gnostic Neoplatonism, was wildly popular among the Army and those connected to the imperial court. And after the Council there were plenty of bishops who took it up as well. Why not just go with it? Of course that religion would have lost Christianity’s Judaism, but it might have been a lot more helpful empire-building wise. Super easy to skootch any pagans you run into into the Arian “Church.” Indeed, the Goths and other Germanic tribes, over the course of the next few centuries, loved it.

But what Athanasius, and the 316 orthodox bishops of the council, said to Constantine and Arius was this: Yes I see what you mean, that would be a more straightforward religion and make things easier politically. But that is not what the apostles taught. That is a new thing. And we have no authority to change what we have been taught. What we can do is describe it: God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten not made.

Ὁμοούσιος τῷ Πατρί

We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of all things visible and invisible, and in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only begotten of the Father, that is, of the substance [ek tes ousias] of the Father, God of God, Light of Light, true God of true God, begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father [homoousion to Patri], through whom all things were made both in heaven and on earth; who for us men and our salvation descended, was incarnate, and was made man; suffered and rose again on the third day, ascended into heaven and will come to judge the living and the dead. And in the Holy Ghost. Those who say: There was a time when He was not, and He was not before He was begotten; and that he was made out of nothing [ex ouk onton]; or who maintain that he is of another hyposasis or another substance [than the Father], or that the Son of God is created, or mutable, or subject to change, [them] the Catholic Church anathametizes.

This is what is called the Nicene Symbol: a σύμβολον, symbolon, was half of a broken object which, when fitted to the other half, verified the bearer's identity. It was fit for purpose: to articulate the old list of assertions in a way that would not permit an Arian to affirm it. But it was not a full creed. That would take another 56 years: it was at the Ecumenical Council held in 381 in Constantinople that this document was fleshed out into something fuller: again, not by way of adding new doctrines, but by way of mentioning what it is that had been handed down, lest there be any confusion.

I believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible.

And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all worlds; God of God, Light of Light, true God of true God; begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father, by whom all things were made.

Who for us men for our salvation, came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Spirit of the Virgin Mary, and was made man; and was crucified also for us under Pontius Pilate; He suffered and was buried; and the third day He rose again, according to the Scriptures; and ascended into heaven, and sits on the right hand of the Father; and He shall come again, with glory, to judge the living and the dead; whose kingdom shall have no end.

And I believe in the Holy Ghost, the Lord and Giver of Life; who proceeds from the Father and the Son; who with the Father and the Son together is worshipped and glorified; who spoke by the prophets.

And I believe in one holy catholic and apostolic Church; I acknowledge one baptism for the remission of sins; and I look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come.

Amen.

Sources and Further Reading

Primary Sources:

Constantine, Edict of Milan

Galerius, Edict of Toleration

Athanasius, Life of Antony

Athanasius, On the Incarnation

Athanasius, The Monk’s History of Arian Impiety

Socrates, Ecclesiastical History

Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History

Canons of the First Council of Nicaea

Julian, To the Athenians

Julian, Against the Galileians

Classic secondary source:

John Henry Newman, Arians of the Fourth Century

Fantastic narrative secondary source:

Rob Bennett, The Apostasy that Wasn’t

Excellent huge Fourth Century online sourcebook which has links to at least partial translations of most of the Nicene documents and relevant correspondence. Run by Lutherans.

More from me about the Cappadocians:

Susannah Roberts, “St Macrina the Younger”

Happenings and Doings

Alastair: After spending the last few months in the UK, I arrived back in the US on Wednesday evening. As I write this, I am sitting next to Susannah in the Birmingham (Alabama) Airport, where we are waiting to fly back to New York (by way of Charlotte). Susannah returned to the US just before Easter and the prospect of being in the same place together for the next couple of months, with minimal travel commitments, is a welcome one.

I spent almost the entirety of the period since our last missive in Stoke-on-Trent, where we had a delightful streak of warm spring weather, of which I took full advantage. Not having travel commitments, most of my time was devoted to writing, teaching, reading, and other work. However, my quieter and more settled schedule allowed me to spend more time with my parents and to explore some parts of the area I had not seen before.

My parents and I went for a walk along an old railway line near Miles Green on the Saturday after Easter. Apart from one muddy patch, the route was perfect for my father’s wheelchair. Most of our walks are around the lake near to their apartment, which is beautiful, but visiting somewhere new was very pleasant.

The following day, after church, the weather was glorious, so I decided that I would take a long cycle ride down the Trent and Mersey Canal to Cannock Chase.

The route took me through Stone and past Stafford. The Trent and Mersey is almost 100 miles long, and, although I cycle on it on a near-weekly basis, I had never cycled beyond Stone. I usually only cycle as far as the Harecastle Tunnel in one direction and Barlaston in the other.

Beyond Stone, the route is quieter and the towpath narrower, but it easy to cycle it. Cycling on the canal, you can fully relax, as there are no cars. You pass ducks, geese, and other birds and creatures, walkers, often with their dogs, the occasional runner, parents pushing infants in strollers, elderly and disabled persons in wheelchairs, other cyclists, and people in barges. Almost everyone is incredibly friendly, and you routinely exchange pleasantries with the people and creatures with whom you share the way. When I leave the canal and return to the road for the last short leg when I am cycling home, I often feel very keenly how, for all its undeniable benefits, the automobile is generally a selfish and unsociable mode of transport, and our places become so much uglier and unfriendlier when we privilege it.

I should also say something about barges or narrowboats, which are truly one of the greatest modes of transport. Almost every barge has its own unique character, often with a whimsical name, colourful paint, flower boxes, piles of logs for its stove, and not infrequently a happy dog surveying passersby. Occasionally one encounters narrowboats selling food and drinks. Inside, they can often be incredibly homely, with all the domestic conveniences for which one could hope.

Much of the route is filled with bird song. There are lambs in the fields and ducklings in the canal, blossom lightly falling from trees, wildflowers on many of the banks, and the occasional canalside pub, where you can stop for a pint and enjoy it all.

Even when you are going through built-up areas, the canal is like an extended nature reserve. Further out in the countryside, there are smaller villages. You can find stands offering fresh farm produce to passersby, with honesty boxes.

At the Great Haywood Junction, the Trent and Mersey meets the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal. The canals provide a scenic cycling network throughout the English Midlands. Without leaving the canal, one could cycle to many of the major cities.

I went a little past the Great Haywood Junction, turning off towards the Shugborough Estate, where I stopped at the Essex Bridge before returning home. I feel ridiculously fortunate that we have so many beautiful places like this on our doorstep. Much as I have grown to love New York and the excitement of living in the heart of the big city, I always miss the English countryside when we are away from it.

One of these days, I will write a more detailed account of the importance of the canals in the history of Stoke-on-Trent and the role played by remarkable figures like the great engineer James Brindley in their construction. Yesterday, I picked up a beautiful Folio Press edition of Samuel Smiles’ Lives of the Engineers in the Strand, an abridged version of the 1874 edition of the work. Smiles writes of Brindley’s canal construction:

When the canals were made, and enabled coals to be readily conveyed along them at comparatively moderate rates, the results were immediately felt in the increased comfort of the people. Employment became more abundant, and industry sprang up in their neighbourhood in all directions… The Grand Trunk had precisely the same effect throughout the Pottery and other districts of Staffordshire; and their joint action was not only to employ, but actually to civilize the people. The salt of Cheshire could now be manufactured in immense quantities, readily conveyed away, and sold at a comparatively moderate price in all the midland districts of England. The potters of Burslem and Stoke, by the same mode of conveyance, received their gypsum from Northwich, their clay and flints from the seaports now directly connected with the canal, and returned their manufactures by the same route. The carriage of all articles being reduced to about one-fourth of their previous rates, articles of necessity and comfort, such as had formerly been unknown except amongst the wealthier classes, came into common use amongst the people. Employment increased, and the difficulties of subsistence diminished. Led by the enterprise of Wedgwood and others like him, new branches of industry sprang up, and the manufacture of earthenware, instead of being insignificant and comparatively unprofitable, which it was before his time, became a staple branch of English trade. Only about ten years after the Grand Trunk Canal had been opened, Wedgwood stated in evidence before the House of Commons, that from 15,000 to 20,000 persons were then employed in the earthenware-manufacture alone, besides the large number of labourers employed in digging coals for their use, and the still larger number occupied in providing materials at distant parts, and in the carrying and distributing trade by land and sea. The annual import of clay and flints into Staffordshire at that time was from fifty to sixty thousand tons; and yet, as Wedgwood truly predicted, the trade was but in its infancy. The tonnage outwards and inwards at the Potteries is now upwards of three hundred thousand tons a year.

The following day, I joined my parents for a walk around their local lake, where we met some friendly squirrels. The banks next to the canal were blanketed with daisies. My father has a sweet tooth, so I had made a banoffee pie (if you have never made one, you must!) for him, which we enjoyed afterwards.

On the Friday, I had a visit from a friend of my father’s, whom I had not seen for several years, which was a real blessing. We walked along the Caldon Canal, through Hanley Park, which sparked my desire to cycle the length of the canal, which I did later in the week.

That week was a sad one for Stoke-on-Trent, as we received the news that Moorcroft Pottery was closing down, after over a century in operation. The past few decades have been ones of decline for the pottery industry, for which the six towns of the Potteries are named; Moorcroft is merely the latest of a series of pottery closures or downsizing. Many of the remaining potteries are struggling due to soaring energy prices and cheap imports.

I did not move to the city until my late teens and, after leaving home for university, largely lived elsewhere until the end of 2018, when I returned to the city. Over the past decade, the city has manifestly deteriorated in many ways and is a favoured location for YouTube channels focusing upon urban decline, frequently appearing near the bottom of the table in various rankings for indicators of social and economic health. The scale of the change is immediately evident, even from a five-minute walk from our house. Nevertheless, I have come to love the city and to feel very much at home in it, not least because of the people. While there is much cause for complaint, concern, and depression as one sees the trajectory of the city, there remains so much to appreciate in the place, and several promising signs of improvement. If one focuses upon the positives, it is a wonderful place to live. Decline is real, but it is only one element of the picture.

Next month, Stoke celebrates the centenary of its city status and, being very disappointed to miss the celebrations (and the eightieth anniversary celebrations of VE Day), I tried to make the most of the city before heading back to New York. The Spode Museum opened a new café just over a week ago, along with an extension of their exhibition space. I visited a couple of times and particularly enjoyed seeing a personal demonstration of the transfer process from a retired ceramics expert, who also had fascinating stories to tell of her many years of experience in the industry.

Susannah teases me for it, but especially since moving back to Stoke, I have become something of a pottery collector. We recently inherited a large set of Royal Worcester Evesham, which used to belong to my grandparents. That is largely for family gatherings and other special occasions. I had some Royal Doulton Larchmont, which my other grandparents used to have (I am passing this onto one of my brothers, as we no longer have a use for it, now we have the Evesham). I have also built up a substantial set of Portmeirion Botanic Garden (almost entirely composed of seconds picked up in sales at the nearby factory store), which is an attractive, yet affordable and heavier duty, set for our daily use. It does not help that, practically every morning, we walk past stores selling new and second-hand pottery at extremely low prices. I discovered a set of plates based on Celtic illuminated manuscripts at a highly reduced price, which I could not resist. I also discovered that Spode had produced a series of plates on British naval history, including a limited edition set commemorating the defeat of the Spanish Armada, about which Susannah was suitably enthused when I informed her.

Recently, when we visited Dagfields, we found a set of Meakin plates with an image of a sailing vessel and New York harbour for £1 each. They were the same set that Susannah’s grandmother used to have in their family home in Forest Hills. The sentimental family association, the connection with New York Harbour (where Susannah used to work), the appeal of the sailing vessel, the Stoke pottery, and the delight of the serendipity and the price is a good example of the way that pottery can serve as a condensation of meaningful associations, elevating objects beyond the fungibility and disposability all too commonly characteristic of consumerism (yes, this is a rationalization of my love of Stoke pottery, but it is a good one!).

Having cycled the Trent and Mersey Canal out to Shugborough on the Sunday, the next Saturday I decided to explore the Caldon Canal, cycling from where it branches off from the Trent and Mersey at Etruria Junction out to Froghall Wharf, around 20 miles in each direction. While I have cycled along the Trent and Mersey countless times (I used to cycle it practically every day for work), I had only cycled only the Caldon Canal a small handful of times, and no more than a half dozen miles.

The Caldon Canal, generally quieter and narrower than the Trent and Mersey, is a pleasant and often scenic route out into the Staffordshire Moorlands. From its beginning at Etruria, it runs through the centre of Hanley Park, goes towards the northeast of the Potteries, out through Milton. The canal, the route for which was surveyed by James Brindley, was first built in 1779 to carry limestone and flint from Cauldon Low in the Peak District. Along its route, there are many reminders of its industrial heritage.

There used to be branches connecting the canal to Leek and Uttoxeter, but these are now derelict or not fully navigable. The old canal network was largely replaced by rail and car. However, it was still used for the commercial movement of some pottery until the 1990s. Nowadays, the canals mostly serve holidaymakers and other leisure purposes.

At Hazelhurst Junction, just before Denford, the old Leek branch divides from the Caldon Canal. It then goes towards the village of Cheddleton, where there is a flint-grinding watermill, next to the Churnet river.

Cheddleton has a heritage railway, the Churnet Valley Railway, which is expanding towards Leek and will hopefully one day connect back to Stoke-on-Trent.

From Cheddleton, I cycled on towards Consall, where I stopped for a meal and a pint of cider in the Black Lion. At Consall, one can see some of the old lime kilns.

The Caldon Canal ends at Froghall Wharf. Hetty’s Tea Shop had closed by the time that I arrived, but I am sure I will return later in the summer. It is an idyllic location.

By this time, it was not long until sunset, so I had to cycle quicker, to avoid cycling alongside the canal in the dark. However, the sinking sun did add to the beauty of the route.

I was flying over to New York the next Tuesday, but, on the Monday, I visited the Great British Food Festival, which was being held in Trentham Gardens with my mother. It was dull and overcast, but we thoroughly enjoyed looking around, perhaps especially seeing the extensive selection of jams and cheeses on offer.

The next day, I got the train up to Manchester, where I flew out to New York by way of Dublin. As my flight was delayed, I came within a whisker of missing my connection in Dublin, where I had to run through the airport.

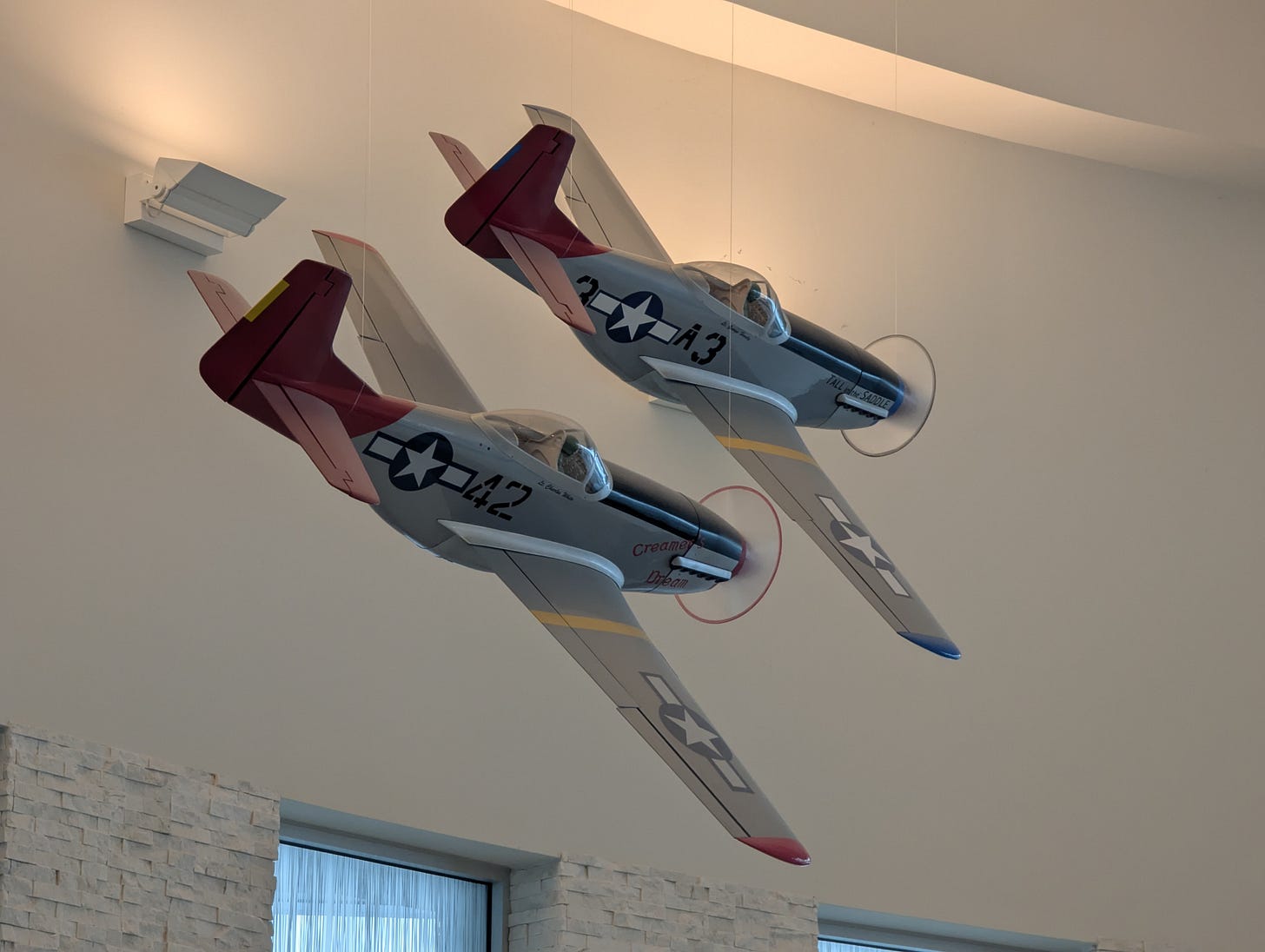

Arriving back in New York that evening, I had no time to settle back in, as the next morning we had to leave for Birmingham, Alabama, where the latest round of the Theopolis Civitas colloquium was taking place. The Civitas colloquium, with which I have been involved since 2019 (Susannah joined a few years later), is a select group that meets in person and occasionally online to discuss political theory and theology, in dialogue with a range of political, historical, economic, and theological texts.

It has been a wonderful contrast to the loudness and shallowness of so many of the political conversations that have occurred in various circles online over the past few years. The fact that several of the select participants have relevant academic expertise or direct government experience, the expectation of close and sustained engagement with academic texts that we are all expected to read, the several sessions over a couple of days, and the more formal rules of discourse raises the bar of the discussion, allowing for far more searching engagement. This session, we continued our discussion of nations and nationalism in dialogue with Joseph R. Strayer’s On the Medieval Origins of the Modern State, Charles Tilly’s Coercion, Capital, and European States: AD990-1992, and Avidit Acharya and Alexander Lee’s The Cartel Systems of States.

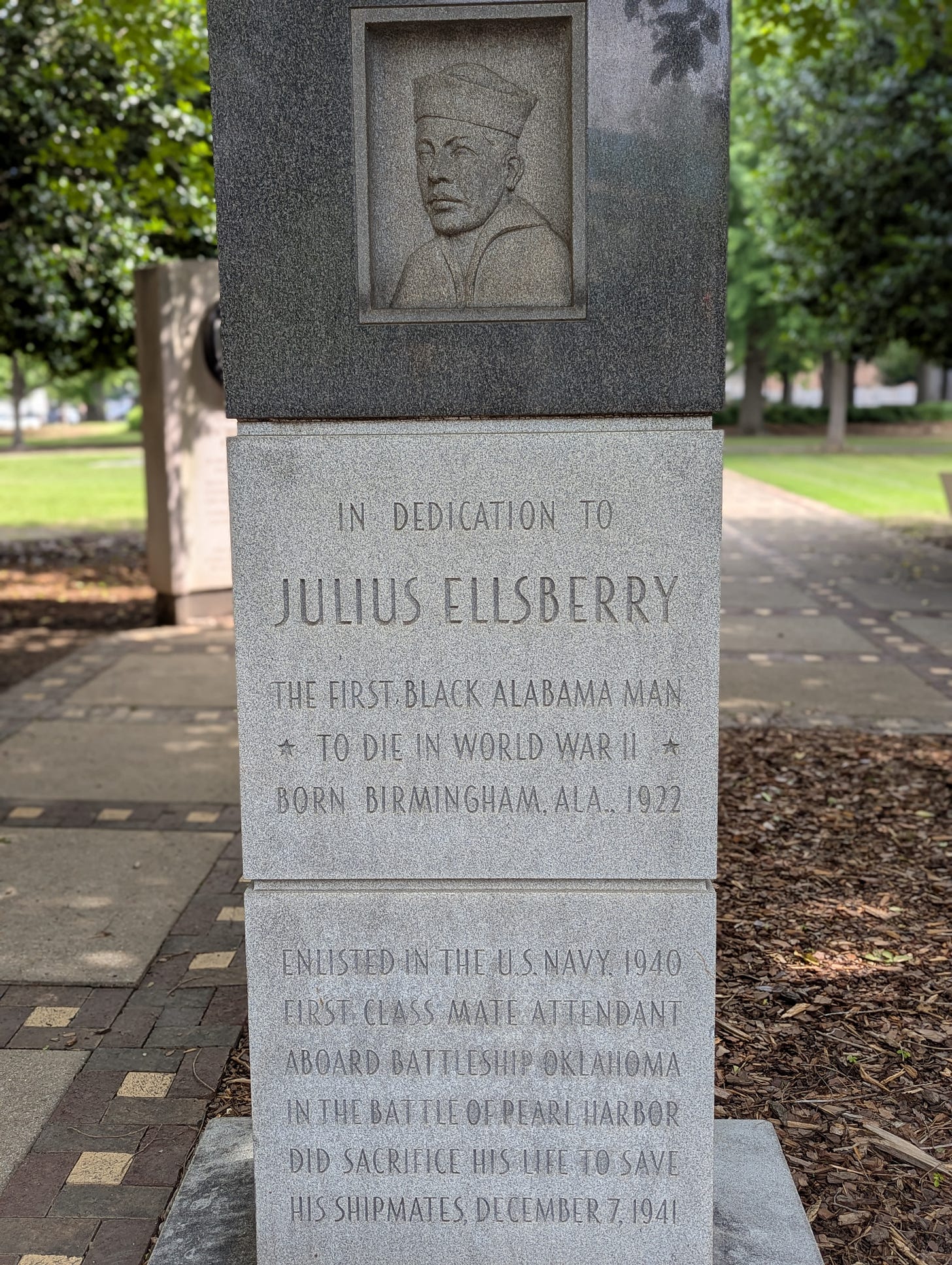

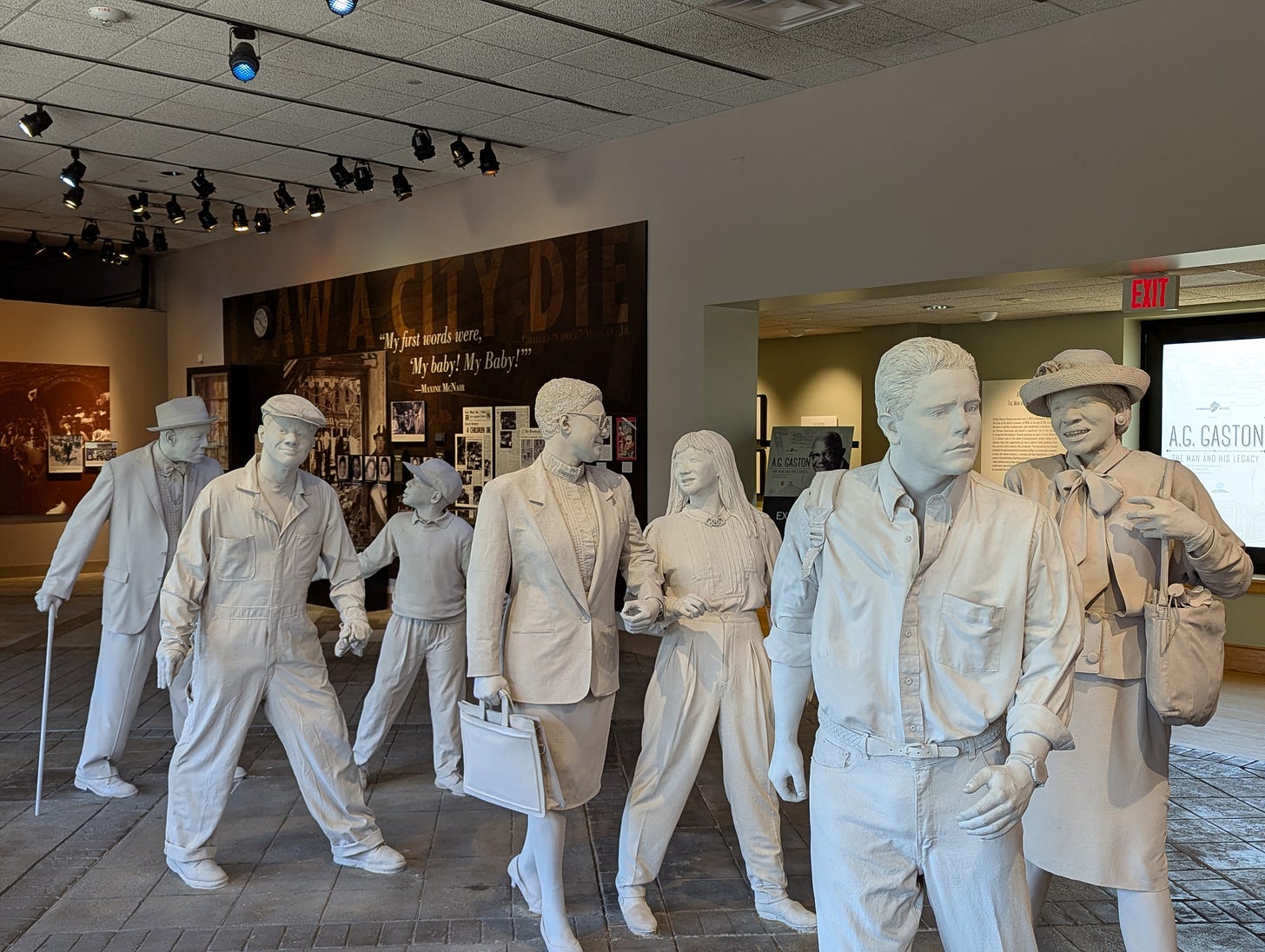

We arrived in Birmingham on the Wednesday, the day before the opening meal of the colloquium, so stayed with Susannah’s former pastor and his family in the city. Having most of the next day off, we decided to pay a visit to the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute.

We arrived a few minutes before the museum opened, so we walked around Kelly Ingram Park. The park is situated across the road from the 16th Street Baptist Church, an important location in Birmingham’s Civil Rights history. It now contains several sculptures commemorating the Civil Rights struggle.

Most notably, on the side of the park directly opposite the 16th Street Baptist Church, it has the Four Spirits sculpture, a memorial to the four girls that were killed in the 1963 bombing of the church.

Walking through the Civil Rights Institute was a moving experience. It tells the story of the Civil Rights movement, focusing upon Birmingham’s part within it.

Visiting the museum on the eightieth anniversary of VE Day was a sobering reminder of the importance of the victories that our societies have won against notable evils in the past, and the imperative that we never lightly value nor carelessly neglect their gains. We have much to consolidate, repair, and build upon in what we have inherited. We heard about the appointment of Cardinal Robert Prevost as the new pope while standing on the steps of the 16th Street Baptist Church waiting for our Uber.

We met with another friend that afternoon, for an all-too-brief yet stimulating conversation. The next few days were devoted to discussion. We flew back to New York on Saturday, arriving in the early hours of Sunday morning.

Although we did struggle to drag ourselves out of bed after our very early morning arrival, Manhattan was gloriously sunny and I was excited to be back at our church here. After the meeting, we joined our friend Hannah and her mother, who was visiting the city, for gelato.

This afternoon (Monday), we met up with Hannah and her parents at Columbus Circle for a walk through Central Park. A couple of years ago, they visited us in the UK and it was great to catch up with them here. The weather here is pleasantly hot, but without yet being sticky and humid, as it tends to be in the summer. We continue to feel incredibly grateful to have such beauty on our doorstep.

Teaching as Feeding

Alastair: In evaluating Christian teaching, merely considering the truth value of isolated statements or the accuracy of certain teachings is not sufficient. Recognition of this reality will both make us more alert to forms of damaging teaching and wiser in our teaching of others.

Christian teaching is often compared to food in Holy Scripture and elsewhere. As with food, there are errors that can be apparent within an individual serving or teaching. However, many errors only become apparent when one considers a longer-term diet.

There are teachers who serve teaching that, taken by itself, might be very worthwhile. Yet, as they keep serving the same narrow teaching and fail to serve other much needed or counterbalancing teaching, they communicate a form of error and their hearers will be malnourished.

You cannot say everything at once, nor should you try to. However, over time you should say a lot of things that help people properly to understand aspects of your teaching that, taken by themselves, are not balanced (yet may be important parts of a balanced diet). It may often be necessary to express a point in a more forceful and less qualified way, while providing qualifications and a sense of how it fits into a more balanced picture elsewhere.

The analogy of teaching and feeding people also highlights the importance of taking responsibility for our hearers’ spiritual health and providing them with a good and balanced diet. One thing that has become more apparent to me over time is that many people, especially online, merely consume teachings according to their appetites and so will selectively latch onto elements of teaching that appeal to them, while refusing the ‘greens’—those less appetizing teachings that are nonetheless essential for a balanced diet.

This is one reason why pastors are so important. Random teachers online can be like fast food restaurants. They can serve highly appetizing teachings, often because they take no responsibility for their customers’ wider diet. There may be nothing inherently wrong with an individual serving of their teaching. Yet, if you were to start living off such teaching, it would soon prove very unhealthy. I have written about my own experience of severe spiritual malnutrition through consuming far too much of certain non-essential elements of a Christian diet, while neglecting the essentials.

Especially in the context of the religious marketplace created by mass and social media, it is very easy for teachers to gain prominence and large audiences through some special sauce of their own that they add to their teaching. Everything they teach will have that distinctive flavouring, often catering to an appetite for confirmation in some identitarian or ideological position. Teaching might consistently return to feminist or masculinist themes, for instance, so that it is more appealing to one sex or the other. In a restaurant, every individual typically gets to choose whatever dish seems most appetizing to them. However, when eating at the family meal table, everyone needs to eat much the same thing; the dishes cannot cater for individuals’ food fads, and picky eaters are rightly judged. A pastor’s teaching needs to feed the seventy-year-old grandmother in the congregation, not merely the sixteen-year-old boy. While each person may ‘inhabit’ the teaching differently, according to their different needs and circumstances, the teaching itself should be ‘catholic’ and, as such, a source of unity and commonality.

A further consideration beyond that of the diet of a family is its food culture, the ways it practices and understands food production, preparation, and eating. Even where all the elements of a balanced diet may be present in a family, it is still possible to have a disordered relationship with food. Failure to eat together, hurried eating, anxieties and disorders around diet and weight, ingratitude, resistance to eating certain unfavoured foods, overeating and under-exercising, constant snacking, are all problems that might have analogies in relation to Christian teaching, perhaps especially in contexts where the ease of access to teachings for us so exceeds our involvement in contexts of practice. We can constantly snack on appetizing Christian teachings online, while failing to metabolize them through practice. When people have experienced contexts where, despite broad orthodox teaching, feeding on that teaching has been an unpleasant chore, where the teaching has consistently been an occasion of division and fighting, where it has not been put into practice, or where the goodness of the food has not been matched with care and skill in the preparation, presentation, and consuming of it, they can often react against the teaching itself. Too many people’s exposure to Christian teaching has been bland and unappetizing slop; the required nutrients may be present, but little joy is to be found in eating it.

As social media creates lots of alienating interactions with people who differ from us, it also encourages a preoccupation with, and teaching focused on, the errors of theological opponents. However, such ‘medicinal’ teaching, which seeks to develop resistance to other groups’ errors, is seldom edifying in the way that Christian teaching ought to be. We are raised to be healthy and strong chiefly by a full and balanced diet of solid food, rather than by lots of medicines designed to protect us from all diseases. Health requires more than the counteracting of disease. There are occasions when we will need medicine, but such occasions are exceptional. Likewise, spiritual health comes chiefly, not from a diet of medicine against all errors that are circulating, but from regular servings of balanced Christian teaching.

When people see some disease or error in the Church at large or in wider society, they can get invested in crusades against it. In such situations, it is easy for the breadth of a healthy Christian diet to be abandoned. The immediate perceived problem at hand becomes such a preoccupation that all teaching starts to be distorted in reaction to it. This problem is exacerbated as the people who become preoccupied with such diseases often end up addicted to the medicine. Repeatedly hearing about the evils of our opponents and the magnitude of their errors can give us a rush of self-righteousness and justified anger, but it is seldom good for us. Medicines, if they are to be of service to health, need to be carefully prescribed and also kept out of the hands of people who would abuse them. Once again, this is one of the challenges of an online context, where audiences are vague and largely self-selecting: it is difficult to prescribe more medicinal truths effectively in such a context.

It is also possible to take certain much-needed medicinal teachings and treat them as universal remedies, or viewing an increasing array of disorders as downstream of the problems they are designed to address. At a point, people who adopt such an approach can move from overhyping a valuable treatment to becoming akin to snake oil salesmen.

Likewise, as such medicinal teachings so often address dysfunctions that are endemic in some opposing camp, a preoccupation with them can often come with a resistance to applying closely related medicinal teachings to one’s own camp. I have remarked upon the dangers of this with the currently popular ‘empathy’ critique, for instance. In its original form in Edwin Friedman’s work, the critique has a much broader application than it is currently given in the work of those who use it to focus upon the errors of those to their left, with many natural and searching applications to dysfunctions on the right. While such a medicinal teaching may be appropriately prescribed to many people on the left, if health, rather than partisanship, is our primary concern it will be extensively prescribed to characteristically right-leaning diseases. It will also be accompanied by an edifying balanced diet that produces health and resilience that reaches much deeper than partisan concerns.

Christian teachers, especially pastors, have a calling to feed people a full and balanced diet of truth in a form that encourages them to delight in it. They need to provide them with occasional well-prescribed medicinal teachings against widespread errors, without being preoccupied about ill-health, allowing such teachings to displace positive teaching, or to prescribe according to the appetite of hearers. Recognizing the value of faithful pastors and the distinctive role that they perform in this area should lead us to accord them special honour, and to be more mindful of the dangers that can accompany some other forms of Christian teaching, especially if we are engaged in it (here I speak chiefly to myself).

Milestone

Today is our third wedding anniversary. These last years have been the happiest in our lives. We could not feel more blessed to share a life together and to face the various adventures that the future holds for us hand in hand. Thank you all for your prayers, support, and encouragement. We are immensely grateful to have such good friends.

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ The Theopolis podcast series on Hebrews continues, with the following episodes: After the Order of Melchizedek (Hebrews 5:1-10), Warning Against Apostasy (Hebrews 5:11-14), and Maturity and Falling Away (Hebrews 6:1-12).

❧ My latest God’s Story Podcast episode in the Zechariah series is on Zechariah 12.

❧ I have written a piece for Logos on liturgy and ethics.

To many, an emphasis on liturgy might seem to be more of a liability than a support for ethics. Admittedly, the relationship between liturgy and ethics can easily be framed negatively. Citing passages from the prophets such as Amos 5:21–27 or Isaiah 1:11–17, where God declares his displeasure in rituals performed by unjust, oppressive, idolatrous, and otherwise unfaithful worshipers, liturgy might be thought of as empty form or mere motions, too often masking hard hearts and unjust hands.

Yet there is another way to consider the prophetic denunciations of such hypocritical worship: It is precisely because of the proper marriage between liturgy and ethics that the hypocritical practice of the former is so abhorrent. The truth of liturgy is not found in bare form, but in comprehensive transformation and reorientation of life and, where the latter is absent, the former is made into a mockery. Liturgy orders us towards practice and is confirmed—and occasionally falsified—in it.

Read the whole thing here.

❧ I was invited back onto the Thank God for Nostr podcast for a conversation on social media.

❧ I have started a new video series for Theopolis.

James Jordan and Time

Time and the Clock

Upcoming Events

❧ Much of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

❧ We are hoping to attend the Davenant Conference this year. It will be held in Resurrection Presbyterian Church, in Matthews, North Carolina, on June 6th and 7th. We would love to see some of you there!

❧ This year’s Theopolis Ministry Conference is entitled ‘Singing the City of God’ and is on the subject of music in the life of the Church. You can find out more about it here.

Much love,

Alastair and Susannah

Thanks so much for this lively historical summary—it was a great refresher but with more details that I knew heretofore.

Every week when we recite the Nicene together in worship, I raise my voice a little bit, with slight ire, at the phrase "NOT MADE!" I think my wife gets slightly embarrassed. But I still feel slightly miffed thinking about it every time.