№ 9: Ascending the Scriptural Path

Also Epiphany and the contrasting strengths and weaknesses of US and UK Protestantism

Dear friends,

I (Susannah) am writing this from New York City, to which we’ve finally both returned after two weeks (for Alastair, and one for me) in South Carolina - for more on that, see below!

We’re in the middle of Epiphanytide, the season after Epiphany, January 6, which marks the day that the Magi found Jesus back home in Nazareth and gave him gifts: gold, frankincense, and myrrh; gold because he is a king, frankincense because that’s the incense that you offer to a god and also what priests offer to god, and myrrh because that’s what’s used for burial: he was going to die.

I am such a fan of the Magi. The whole thing is very weird. A bunch of Zoroastrian magicians/astrologers show up at Herod’s court in Jerusalem and say, not very tactfully, “Where is he who has been born king of the Jews? We saw his star when it rose and have come to worship him.”

A) Why Zoroastrians B) I thought astrology was a big nope in the Bible/for Jews and Christians C) What on earth is going on here? “We saw his star when it rose:” the only sensible response is “you what with the what now?”

People have various theories about why these miscellaneous non-Jewish astrologers had what was apparently Gentile backchannel knowledge of the Jewish messiah. One theory is that they had had it handed down to them from Daniel, who had famous run-ins with Nebuchadnezzar’s court astrologers/magicians, and who was still alive when Babylonia was conquered by the Medes and the Persians; the Persian Empire, Cyrus’ empire, was Zoroastrian. It’s all very weird, and is not enough to make me take up astrology, but it does make you wonder.

In a kind of big-picture way, which slightly contradicts the above account, the Magi are often thought of as “the best the Gentiles can do on their own,” the best we can do with natural reason and science/wisdom traditions/philosophy. And that is, apparently, pretty good. Plato got pretty far along, theism-wise. You can get to approximately the right place, and then you have to ask directions. And it’s at that point, when you ask directions, that the surprising stuff starts: you knew by natural reason that there was a God, but naturally, you looked for him in a king’s court, and he wasn’t there. This is where revelation has to step in: the King of the Jews was actually the toddler in Nazareth.

It’s a wonderful and bizarre story, and gets shoved in with the Christmas story because Jesus is still little when it happens, and because there are presents involved, but it’s not really part of it. And this is the part of the year we’re in right now: the part where the Gentiles have gotten as far as they could, and that was pretty good, but they needed revelation to get where they needed to be. It’s a good time of year to read popular cosmology books, in my opinion, so that’s what I’ve been doing.

Holding Literal and Spiritual Reading Together

Alastair: There has often been a perceived antagonism between so-called ‘literal’ or ‘historical grammatical’ readings of Scripture (‘historical grammatical’ isn’t straightforwardly synonymous with ‘literal’) and readings termed ‘allegorical’, ‘figural’, ‘typological’, ‘symbolic’, or ‘spiritual’. It has long been a concern of mine to maintain that, not only is there is no opposition in principle between careful ‘literal’ reading of Scripture and such readings, but that attentive hearing of the literal sense of Scripture will consistently move us in such directions.

Such a movement is not to the abandonment of the literal sense (whether the proper or improper literal sense), nor an evacuation of its import, which has always been a danger of the spiritual sense wrongly applied. Indeed, the New Testament can make truly startling claims about events such as those of the Exodus, for instance, recognizing Christ’s presence and agency at the heart of the events recorded in the Pentateuch. While it is common to see events such as the Exodus as figures of the spiritual realities of Christ and his kingdom, in 1 Corinthians 10, for instance, the Apostle Paul reads the spiritual realities associated with the antitype back into the type:

For I do not want you to be unaware, brothers, that our fathers were all under the cloud, and all passed through the sea, and all were baptized into Moses in the cloud and in the sea, and all ate the same spiritual food, and all drank the same spiritual drink. For they drank from the spiritual Rock that followed them, and the Rock was Christ.—1 Corinthians 10:1-4

While the antitype is an escalatory realization of that which the type anticipated, the type and antitype are not discontinuous realities. Christ, the Apostle implies, was present and active in the historical events of the Exodus and the conquest. While the events of the Exodus were types of a greater reality, the reality was also mysteriously present and operative within its anticipatory types.

Revisiting the Old Testament account, we may recognize ways in which Paul (perhaps assisted by the Jewish legend of the moving rock) could have grounded his claims within the scriptural account. As Peter Leithart observes, the Pentateuchal account associates the Lord and the Rock, notably in Moses’ song in Deuteronomy 32 (verses 4, 15, 18, 30-31) but also in the Lord’s standing before Moses when he struck the rock in Horeb (Exodus 17:6), perhaps as the theophanic Angel of the Lord (Exodus 23:20ff.) or as the glory cloud.

The association of that rock with the other rock of Numbers 20, another notable miraculous rock at a place called ‘Meribah’ from which Moses was instructed to summon forth water for the entire congregation, suggests that, even if they were not physically the same rock, symbolically they were (perhaps we might also speculate about the connection between this rock and the rock in whose cleft Moses sheltered in Exodus 33:21-22 and the rock from which the tablets may have come). The typological character of the rock is further suggested by the seriousness of the Lord’s directions concerning the contrasting manners in which the waters were to be summoned from it. Likewise, that Paul would connect the rock with Christ makes a lot of sense when we consider the way that the Lord associated himself with the struck rock in Exodus 17 and Moses’ use of the term ‘Rock’ as a name for the Lord. In short, the spiritual reading of the Rock is encouraged by the very events recorded in the scriptural narrative and not merely imposed by later readings.

The rock gave the people water to drink and preserved their lives in the wilderness, as an expression of the Lord’s own personal presence and provision. In John’s gospel especially, both Jesus and the Evangelist may be drawing upon the accounts of the Rock in the wilderness. Much as he describes himself as the true manna in John 6, Jesus presents himself as the one from whom the living water of the Spirit will come (John 4:10; 7:37-39). When struck with the spear, blood and water flow from the side of Jesus, a detail upon which the Evangelist places such significance that he stresses the reliability of the witness to it (John 19:34-35). Allusions to Ezekiel 47 and the water flowing from the side of the temple may also be behind the account of the great catch of fish in John 21. Jesus is the true temple (John 2:20-22) and the one from whom the eschatological living waters will flow (cf. Zechariah 14:8).

The events of the Exodus gestured beyond themselves in ways that invited the Israelites to experience them as anticipations of greater deliverances and realities they still awaited; much as the miracles and signs Jesus performed during his earthly ministry, they were genuine promissory foretasting of what would later be enjoyed in fuller measure. While they signified something greater, an escalatory development beyond themselves, that development would by no means be discontinuous with them: we cannot treat the events of the Exodus as signs empty of the realities to which they related. Christ was truly present with and leading the Israelites in the wilderness (1 Corinthians 10:9; Jude 5).

Our understanding of the Old Testament must operate accordingly: spiritual hearing of the Exodus must neither neglect the concrete events to which the scriptural accounts bear witness, nor treat regard the literal, ‘exoteric’ sense of those accounts as something to be effaced or displaced by an alien allegorical sense imposed upon them. Rather, the spiritual sense emerges from meditation upon the literal sense and the historical realities to which it refers.

Such a position opposes both those who emphasize a mere historicity and the exoteric sense to the exclusion of allegory and those who pursue allegory to the erasure, evacuation, or denigration of the exoteric sense and the events it records.

A challenge here is recognizing the groundedness, the continuity, the temporal development, and the escalation of the meaning of the Scripture. Perhaps we can compare it to a long trek through wooded and rocky terrain towards the summit of a great mountain. As you follow the path, there will be occasions when you attain some partial and limited vantage point from which you have a clearer view of parts of the route that you have travelled and perhaps also a glimpse of your intended destination. However, much of the time your vision will be restricted to the path immediately in front of you. As you steadily ascend the mountain, your range of vision will likely expand and the route that you have taken will become both more visible and understandable.

When you finally attain the top of the peak, the entire path that led you to that point, formerly only perceived in parts, can unfold as a visible unity. Your perspective is not that of a detached observer, nor is it any longer the limited perspective of the walker on the way. Your vantage could only be reached by walking the path that led you to the point where you are standing, but, as you look down upon it in its totality from your high elevation, the path now assumes a very different aspect. From the point of the path’s destination, both the end of the path and its unity become apparent. The path was always designed to get you to the point that you are standing, a point from which the terrain you passed through, which constrained and obstructed your vision, opens before you and can be seen anew.

So it is with our reading of Scripture. The path of the Scripture leads us to Christ, from whom all takes on a new aspect. However, to attain to Christ, we must attentively follow and regard the path which scriptures furnish us, not straying from the letter of the scriptures, keeping our feet firmly on the ground of their historical witness, confident in the promise that they will grant elevation to those who faithfully follow their path. Such attention is rewarded when the person enjoying the elevated vantage point afforded by the New Testament—a vantage point only enjoyed by those who never ceased to be grounded upon the scriptural path—can marry their remembered vision when looking up and forward to their current vision looking down and back.

Protestants Across the Atlantic

Living, traveling widely, and having attachments on both sides of the Atlantic, I spend a lot of time considering both the UK and the US and their Christian subcultures from inside and outside perspectives. As the countries share a common language and have extensive cultural overlap, divergences and interactions between the US and UK can be fascinating and illuminating.

My intellectual formation as a Christian was one in which American influences arguably played a disproportionate large role. My father had an extensive library and many business and other dealings with American Christians. The contemporary theology that shaped me principally came from US theologians and writers. When I became more active in online theology fora and in blogging, almost all my interlocutors were American. Although I studied at British academic institutions the theological conversations that were most formative of my theological interest were American. These conversations bridged something of the gap between the world of the thoughtful and well-read lay person and the world of theological scholarship.

Outside of the Internet, such conversations have always seemed extremely few and far between in the UK. The US has marked problems in the areas of Christian catechesis, education, and formation, but they are far less systemic and pervasive than corresponding problems in the UK. Although the typical Christian in the US has an embarrassingly low level of literacy in the faith, American Christians have much more potential for increasing such literacy than their British counterparts.

Robust networks of Christian schools and homeschoolers, serious catechesis, all-age Sunday schooling, and institutions advancing lay theological literacy are virtually non-existent in the UK, while there are many places where these things are occurring in the US. Such lay Christian education, perhaps assisted by the more selective and market-driven character of ecclesial affiliation in the US, can be effective at producing settings with a relatively high general level of Christian literacy.

Compared to the US, there are virtually no resources and institutions serving the ends of intensive and extensive lay education and formation in the UK. My audience is overwhelmingly American, for instance, because there is such a limited audience for such work in the UK. My work isn’t produced for an academic audience, but there isn’t an extensive theologically literate audience of lay persons in the UK. There are also few platforms and institutions supporting such work in the UK. Indeed, while the UK has produced several leading theological communicators over the past century, these communicators are often most popular in the US.

However, despite the fact it feels like a wasteland when it comes to lay education, the UK has been very effective at producing leading Christian thinkers and public voices—and, ironically, even lay educators!—especially among Protestants. Despite being more secular socially and rarely exceeding a low level of theological general literacy in its churches, the UK has punched well above its weight in producing the elite of conservative Protestant thinkers.

If you look at the academic background of a great many leading American conservative Protestants, you’ll routinely find that they did doctoral studies in a UK—or occasionally European—university. Likewise, if you consider some of the towering influences upon American conservative Protestantism theological thought, you will also notice British figures are rather overrepresented among them: men like C.S. Lewis, F.F. Bruce, John Stott, J.I. Packer, N.T. Wright, Carl Trueman. It is worth considering why.

I see several dynamics at work. The UK has top-tier universities where conservative Protestant thought can truly occur in public. This tends to be more effective at producing rigorous thinkers of the highest calibre. It also allows for greater prominence. By contrast, when they were met with institutional and cultural hostility, conservative Protestants in the US, partly on account of their greater numbers and resources, were in much more of a position to leave public and mainline institutions and devote themselves to their own ‘subaltern counterpublics’. In the UK, evangelicals remained in the mainline Church of England and did not abandon ‘impure’ institutions for their own pure ones.

Through the combined push-and-pull pressures of the hostile marginalization of them within or ejection of them from the mainline denominations and the attraction of their subaltern counterpublics, conservative Protestants in the US largely ceased to do their thinking in public, retreating to the greater safety of their own institutions. One effect of this was the siloing of much conservative Protestant thought in the US. Having a smaller pond to yourself can offer protection from predators and pollutants, but it is also more likely to be stagnant, marginal, or to inhibit the growth of some beyond a certain point. People who, in a different context, would have the intellectual calibre to rise to some measure of public prominence cannot do so when constrained by the modest bounds of their own small pond. More could be said about the way that such entities tend to arise much more readily in the US on account of the fact that American conservative Protestants are a vast constituency (likely larger than their British counterpart by at least an order of magnitude), which functions more according to market principles.

This can be especially inhibiting for conservative Protestant academics in the US. There are some brilliant thinkers who are constrained by the fact that they are operating in very small ponds with few real academic peers and no meaningful academic elite to which to aspire. This leaves them lonely and isolated, devoting too much time to engagement with interlocutors of low theological calibre. Their audiences can be overly friendly to them or petty, preoccupied with pointless conflicts in which such promising thinkers can get snarled up.

This is one of several reasons for the appeal of Rome for many Protestants in academia. Rome has not siloed its thought to the same degree as conservative Protestants and is much better at cultivating and institutionally sustaining an academic elite, so there is the promise of intellectual rigour, true intellectual peers, and a meaningful public influence extended to those who swim the Tiber. This will be attractive to many. Likewise, the lower quality of academic discourse that conservative Protestant subaltern counterpublics can sustain is likely also a factor discouraging some first-rate thinkers from considering a vocation as Protestant intellectuals at all. The calibre of academic discourse in American conservative Protestant circles has so often been so low compared to other fields of American academic discourse.

We must consider the power of network effects upon the quality of an intellectual culture and how this affects the growth and can increase the capacity of the best thinkers. Thought—and communication more generally—is one of those areas where repeated partially receptive exposure to robust opposition or alternative viewpoints can be strengthening. This can be important for public engagement. Those formed in more public institutions will be much more adept at communicating in idioms that are accessible and understandable to a wider audience, who might not share their specific theological commitments. Such persons will probably be better prepared to communicate the faith to thoughtful non-Christians, being more accustomed to such communication in general.

Further, thought is an area where the quality and scope of one’s interlocutors will greatly constrain or expand your own potential. The most productive intellectual environments draw extremely selectively from a vast population and allow for highly specialized elite formation. When an institution or context routinely and selectively brings people of the rarest aptitude into direct and extensive sharpening interactions in an intellectually catalysing environment remarkable things can be achieved. When contexts are drawing much less selectively from smaller constituencies and greatly restricting direct exposure to smart opponents, there will be a much lower ceiling upon the levels of excellence, prominence, and influence that can be achieved.

Indeed, the presence and prominence of poorly-formed thinkers of lower aptitude in such contexts can act as a constant drag on the potential of intellectual conversations within them. If you can reasonably presume that your interlocutors are all quite familiar with, say, Plato or Aquinas, and have considerable philosophical acumen, you will be freed to have conversations on a completely different level than you would if your time was occupied with addressing the most elementary misunderstandings and there were no high hurdle of knowledge and expertise required for entry into the conversation.

Although many American conservative Protestant thinkers may feel the lack of a culture conducive to high-level academic thought, public engagement, and intellectual growth and companionship, it is important to consider the trade-offs here. In part at the cost of such things, American conservative Protestants have proven much more effective than their British counterparts in cultivating a broader Christian intellectual formation. They may not achieve the intellectual peaks that Protestant thought might be able to achieve in some British academic institutions, but they are doing a much better job of mitigating the depths of lay Christian ignorance and protecting the Church from dangerous exposure to error than their British counterparts are!

In the UK, where there are so few institutions and resources devoted to extensive lay Christian formation, although there can be great exemplars of Christian thought in public, for most Christians theological formation is slight or near non-existent. And without a robust culture of lay education and the institutional structures and resources to support it, British lay educators will tend to be drawn to the US.

Without institutions of their own, British Christians can be highly susceptible to assimilation or mute deference to prevailing cultural values and, where there is resistance, it is often much less effective and more ad hoc than it is in the US. Not having their own ‘ponds’, they are forced to the margins of the big pond of a more general British society.

Living between the US and UK, I would love to see Christians in the US take some lessons from the UK, to start to resist their self-siloing, and do their thinking more in public.

I would love to see Christians in the UK take lessons from the US and seriously pursue lay formation. This would likely require moderating their investment in some more public institutions, as homeschooling or Christian schooling became more common, for instance, without forgetting that one of the strengths of British Christianity is the fact Christians are genuinely invested in public institutions.

Boundaries are a key issue here. Healthy formation of faithful children requires more effective and extensive boundaries and protection than British Christianity provides. The American approach, by contrast, can be overly dependent upon boundaries. The British approach can produce a Christianity that is weakened by overexposure to hostile environmental pressures. The American approach can produce a Christianity that is weak through underexposure to the sort of pressures that can spur growth, not being receptive enough to its critics.

What we all need to develop are the sorts of boundaries that render us robust enough to operate non-reactively in hostile environments, maintaining a healthy spiritual self-regulation, while not being impermeable or hostile to our environment. We need to grow through routine thoughtful exposure to sharpening criticism and opposing viewpoints, exposure which isn’t simply antagonistic but retains some receptivity.

Although Tim Keller’s approach is certainly not without its weaknesses, it has this strength over its critics. A commitment to receptive, charitable, and thoughtful engagement in public, beyond simple opposition, offers a more expansive repertoire with which to address wider society than most pugilist alternatives. It can also produce more rigorous thinkers. As the society at large grows more hostile, thinking in public may come with increasing costs and offer fewer rewards, but we should be under no illusions that we are sacrificing or losing some exceedingly valuable goods when we retreat or are driven from public intellectual discourse. Nor should we be unaware of the inhibiting effect that pugilist impulses—wherever they arise upon the political spectrum—can have upon careful thought. They tend greatly to limit the scope of attentive and receptive engagement with alternative viewpoints and reduce scholarship to the underwriting of party interest.

It isn’t hard to see the deterioration of thought that typically occurs when a group’s world of thought and discourse splits off from the mainstream, from the public, and/or from a shared world with its critics, increasingly serving chiefly to confirm an audience in their priors. The challenge then—one facing British and American Christians on different fronts—is that of maintaining healthy self-definition in public. We need to resist self-siloing or excessive entrenching of ourselves against our cultures, while also resisting overexposure or assimilation to them.

As someone whose work occurs in the space between lay, ordained, and academic audiences, who operates in both the US and the UK, who sees considerable strengths and weaknesses in conservative Protestantism on both sides of the Atlantic, and who is actively forming new networks and connecting with existing ones, these are matters that frequently occupy my thoughts.

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ On the Theopolis podcast we have discussed the twelfth and thirteenth chapters of James Jordan’s classic book on the reading of Scripture, Through New Eyes. We looked at the Garden of Eden and Noah and his Ark.

❧ Susannah joined the Mere Fidelity cast for a discussion of MAID in Canada and the ethics of ‘assisted dying’. Andrew, Matt, and I debated the apparent antisemitism of 1 Thessalonians 2:14-16 the week before.

❧ I had the privilege of appearing on Ari Lamm’s wonderful Good Faith Effort podcast, for a delightfully expansive exploration of the question of how to read the Bible.

❧ A two-part treatment of mine on the subject of the Sabbath was published on The Biblical Mind website over the last fortnight. You can read the first half here and the second half here. Within the pieces I make a broader argument about the way that the Old Testament works and consider what it means to meditate upon it.

Throughout Scripture we see condensations and expositions of the law and persons’ understanding of the law manifested in their facility in moving between the two. At times, wisdom is demonstrated in the ability to comprehend the entire law in condensed principles. Most famously, when asked which of the commandments was the greatest, Jesus summed up the entire law in two great commandments: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind” and “you shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Matthew 22:36–40). At other times wisdom is demonstrated in the perceptive and creative application of more abstract principles to a variety of specific circumstances.

The law itself has a structure that invites and encourages sustained meditation upon and familiarity with the relationship between condensed principles and expounded applications, between specific commandments and the larger system, and between positive practice and negative proscriptions. Perhaps the most significant example of this is found in the book of Deuteronomy, where the Ten Words of the covenant (commonly referred to as the “Ten Commandments”) in chapter 5 are followed by twenty-one chapters of exposition (chapters 6 to 26), within which various dimensions of each of the Words’ application are expounded in succession.

❧ I joined Peter Mommsen and Susannah on the PloughCast to discuss my recent Plough article on Matthew’s genealogy.

Happenings and Doings

We’ve spent much of the past fortnight at the Davenant House, in the picturesque foothills of the Blue Ridge mountains. Alastair has been recording a twenty hour-long lecture series for Davenant—‘An Introduction to Biblical Wisdom’. Watch this space: it should be available for purchase in the next couple of months!

It was Alastair’s first time back to Davenant House in three and a half years; Susannah had never been there before and fell in love with the place. The Davenant Institute as an organization has been incredibly important to us both—and played no small part in bringing us together—and its distinctive ethos is quite tangible at the Davenant House.

Besides the lectures and preparation for them, and the regular work and teaching that we had to do (in total, Alastair recorded over thirty hours of material over the last two weeks), we enjoyed spending time with and getting to know the students doing residential stints at the House. Spending time at the Davenant House and with some students in person brought home to us both again how privileged we are to be involved with the work of Davenant.

Brad and Rachel Littlejohn and Michael and Lynette Hughes and their families are the most delightful hosts and it was wonderful to have the opportunity to spend proper time with them all again after so long. We ate well, had thoughtful conversation, and played lots of board games and baked a few desserts with the children.

While at the House, we were also able to catch up with several friends in the area and to make some new friends. We visited Greer and Greenville, seeing the stunning Falls Park, being treated to a meal at the Between the Trees restaurant in the imposing new Grand Bohemian Lodge, and browsing in M. Judson Booksellers.

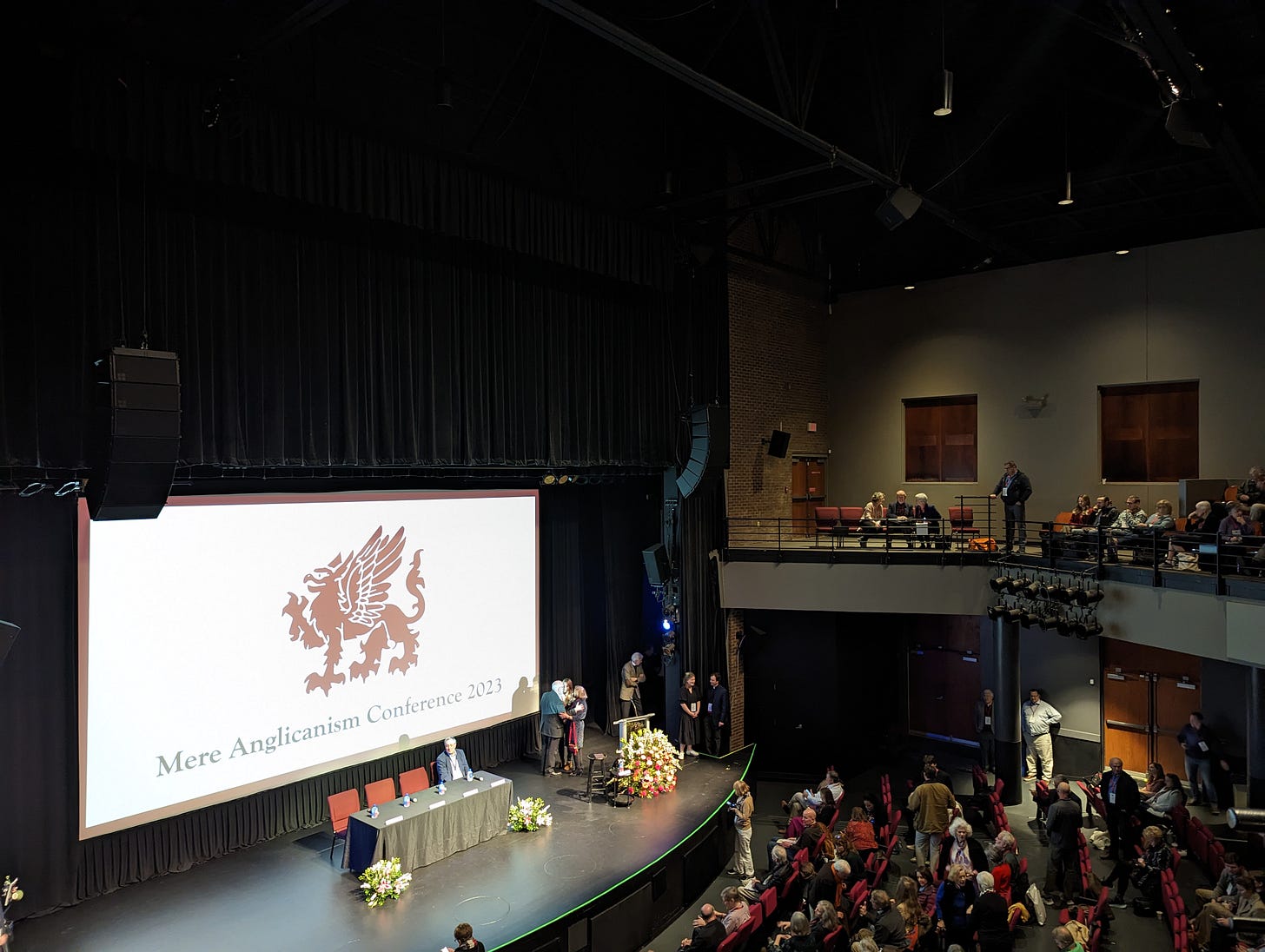

Susannah returned to New York on the 21st, but Alastair stayed on until Thursday, travelling down to Charleston for the Mere Anglicanism conference on Friday with Brad and Paul Shakeshaft. The conference, focused on C.S. Lewis, was superb. They got to hear Simon Horobin, Jerry Root, Michael Ward, and Alister McGrath. The Festival Eucharist service at St Philip’s Church, with Archbishop Foley Beach as celebrant, was memorable, with some of the most wonderful music Alastair has ever heard in a church service, not least because the choir and musicians were matched by spirited congregational singing. Alastair had never seen Charleston before and wants to visit again; as a city it has such a distinctive character and charm and, of the dozens of US cities he has visited, it is likely to become one of his favourites.

During and after the conference, Alastair had the opportunity to meet and catch up with several friends and acquaintances. One of the highlights was meeting up with Kenneth Padgett, a PhD student whose project he will probably be supervising. Kenneth is the co-founder of Wolfbane Books and Alastair, Brad, and Paul had the privilege of hearing his remarkable conversion story and also about the thoughtful creative process by which Kenneth, his co-author, Shay Gregorie (whom they also had the delight of meeting), and their illustrator, Aedan Peterson go about creating their children’s books, which, whether considered on a theological or an artistic level, are truly outstanding.

After Alastair arrived back in NYC late Sunday afternoon, we enjoyed the latest in a series of evenings in which Hannah Long is introducing us and other friends to classic movies, especially Westerns. Last night we watched Sullivan’s Travels (1941) and Ride the High Country (1962).

Upcoming Events

❧ Some exciting news on the Davenant front: through a new collaboration between the Davenant Institute and Union Theological College (Belfast), Alastair will now be supervising PhD students at Union.

❧ The forthcoming Theopolis Workshop on ‘Numberology’ is open for registration.

Numbers are found all over the Bible, in many different forms: in death tolls, ages of famous individuals, enumerations of geographical features, in the counting or ordering of hours, days, and years, in physical measurements, quantities of materials, among many other examples. They are found in stories, in visions and prophecies, in genealogies, in censuses, and elsewhere. Some are clearly visionary and symbolic, others concrete and historical.

This course will demonstrate their importance as frequent and integral elements of the biblical text and its narratives. It will explore the ways that numbers are seamlessly related to the literary, theological, and typological forms of Scripture, and vehicles of its theological and spiritual communication. Students will learn skills by which they can discern the import of various biblical numbers, while also developing the caution and care that will help them to guard against speculative excesses or departures from the biblical form of numerology.

❧ Watch this space for Alastair’s Davenant Hall course on ‘A Biblical Theology of the Sexes’, starting in mid-April.

❧ If you like the sound of the Davenant House, you can join Alastair when he returns there to teach at the summer program in June!

❧ Most of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Susannah and Alastair

Just when I'm sitting down to do some sermon work on Mark 2:23ff, along comes this with the links to your pieces on the Sabbath - nice timing, guys! Also, re those articles I find this acronym a great short-hand: LAW = Love At Work (in its favour is a brevity that allows for elaboration). Blessings to you both.

Just wanted to say, thank you both for all the hard work you put into sharing your love and your scholarship.

I'm not Catholic or Protestant but I am deeply grateful to learn ever more about scripture from a scholar who has deep faith in addition to the knowledge gained over years of study.