№ 51: How Not to Write a Hot Take

Also escaping 'covenant' overload, ecclesiocentrism, and visits to Charlotte, Governor's Island, and the Bruderhof

Alastair: We are now most of the way through our current US stint. At the end of this month, after some time in Birmingham with Theopolis and a few days in Connecticut with Susannah’s extended family, I will return to the UK, where various family members will be visiting. Hopefully, there will be a chance to catch our breath.

On the evening of Sunday 15th I was to fly down to Charlotte where, at relatively short notice, I was going to help Joseph Minich lead a group of Davenant students in a course on political theology. As I did not have to leave for the flight until late in the afternoon, after church Susannah and I wandered in Central Park for a while.

Susannah had been wanting to visit the Sargent and Paris exhibition in the Met for several weeks and, as we had an hour and a half to spare, we took the opportunity to visit it. Having the Met on our doorstep is one of several advantages of living where we do.

John Singer Sargent was an expatriate American painter, renowned for his portraits. The exhibition focuses on his work as a society painter in Paris, from May 1874 until the middle of the 1880s.

After his training in the Academy of Florence did not work out, Sargent returned to Paris, where he enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts. During his period as a student there and in the years that followed, he travelled widely, and especially influenced by the Impressionists, painted various landscapes, seascapes, local people, and other outdoor scenes.

Sargent’s work was also influenced by that of Diego Velázquez, a leading Spanish Baroque artist. Indeed, Sargent produced several copies of Velázquez paintings, of which the Met exhibition had a few on display. Perhaps most striking of these is his version of Velázquez’s most famous work, Las Meninas.

The heart of the exhibition are the portraits he produced from 1879 to 1884, a period of exceptional productivity and rising fame for Sargent. His portraits of children are perhaps peculiarly arresting: The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit and Edouard and Marie-Louise Pailleron both captivate and unsettle the viewer.

The exhibition leads up to Sargent’s renowned Portrait of Madame X, famous in large measure for the controversy that its unveiling occasioned. Before you arrive at it, however, the exhibition tells of the rise of the figure of La Parisienne, the fashionable woman of Paris society. Several portraits of such women from contemporaries of Sargent contextualize Sargent’s own treatment of the subject.

Madame X presents the figure of Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, a glamorous socialite who was celebrated in Paris society, an American expatriate like Sargent himself. When exhibited in 1884, Sargent’s painting of Gautreau was the cause of considerable scandal, largely on account of the suggestive manner of her appearance (in the original version of the painting, the right strap of her dress had fallen to the side of her shoulder). Gautreau herself was mortified by the public’s reaction and rejected the portrait, even though she had initially considered it a masterpiece. Sargent left for London, taking the portrait with him.

I left for the airport shortly after returning to our apartment. Unfortunately, my flight was greatly delayed, so I did not arrive at the Airbnb in Charlotte until the very early hours.

Over the course of the week that followed, I led the students through a discussion of the biblical witness on political theology and through readings from a series of texts: Brad Littlejohn’s Called to Freedom, Richard Hooker’s The Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, Oliver O’Donovan’s The Ways of Judgment, Johannes Althusius’ Politica, and James Wilson’s Lectures on Law.

The Airbnb in which we were staying was next to Lake Norman and, as the weather was glorious for much of our stay, we kayaked on the lake and enjoyed the sun. I had not expected to be back in the Charlotte area just a couple of weeks after having been there for the Davenant Conference, but it was great to spend more time with Joseph Minich and to teach some Davenant students. I continue to be impressed by the calibre of the students Davenant’s programmes attract.

On the Friday evening, I was to fly out from Charlotte to return to New York. While the airport itself is a pleasant one, in my personal experience, flights to and from Charlotte Douglas International Airport have, perhaps more than any other airport, been afflicted by delays and cancellations. Once again, my flight was hit by a succession of delays and I did not arrive back until the early hours.

The Friday had been my birthday and, as I had not been with Susannah for it, she decided that we would have a celebratory outing on the Saturday instead. We were joined by our friends Ben and Sarah Miller, whom we had bumped into on our flight back from Charlotte a couple of weeks earlier.

Susannah used to work with the Harbour School on Governor’s Island and, as neither I nor the Millers had visited it, she took us there for the day. For my birthday last year, Susannah had taken me on Clipper City, the schooner on which she used to work. It seemed fitting that this year we visited another important place for her that I had not yet seen.

After the Millers arrived, we took the Subway to South Ferry, where we caught the ferry to Governor’s Island. On the way, we passed the ventilation building for the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel that is used as the Men in Black’s headquarters in the movies.

On the island, we first went to Fort Jay, a bastion fort that once served to defend the Bay. Governor’s Island had been occupied by the British during the Revolutionary War. Various gun emplacements and earthen fortifications had been set up there by both the revolutionaries and the British. After the War, Fort Jay was first built, initially with wood and earth, named for John Jay.

The fort would later be given stone and brick walls and became part of a network of defensive forts for the Harbour. During the Civil War it held Confederate prisoners of war. In the 1930s, the barracks in the fort were converted to family apartments. The fort was closed in 1964.

There is a sense of surreality on Governor’s Island. Within sight of Wall Street, it has a farm, a site devoted to composting, and events such as an annual Jazz Age lawn party (Susannah wants me to go with her next year). It has a former barracks, Liggett Hall, which was one of the largest such buildings in its time, and lots of other former residential accommodation and service buildings. As so many of the buildings are protected yet abandoned, the island feels a little spooky in places.

The New York Harbour School, a public high school with which Susannah used to work, now occupies a large and attractive building on the island. The Harbour School is a unique establishment, which I am sure Susannah would like to describe at some point. During her time there, they started the Billion Oyster Project, intended to restore oyster reefs to the harbour. Oysters are a keystone species and crucial for the health of the harbour. Manhattan used to have a level of biodiversity comparable to that of places like Yellowstone and the ecological work of the Billion Oyster Project is playing a small part in restoring something of what was lost to human settlement and use.

The majority of Governor’s Island—103 of its 172 acres—is artificial, formed using material excavated from the Subway in the 1890s and early 1900s by the Army Corps of Engineers. More recently, the southern part of the island was landscaped, with four small hills being formed, from which one can enjoy stunning views out over the Harbour.

After wandering around other parts of the island, we went up Outlook Hill, from which we could see across to New Jersey, the Statue of Liberty (while surrounded by New Jersey waters, the Statue itself belongs to New York, much to Susannah’s relief), Ellis Island, and the skyscrapers of lower Manhattan.

We walked the long way around the island back to the ferry, returning to the city. We walked towards Pier 15, and shared a meal, before the Millers headed home. It could not have been a happier day.

The next day, Susannah was tired after church, but I briefly met up with some of our friends in Central Park. After parting from them, I spent some more time wandering through the Park, going to Bethesda Terrace, which has beautiful Minton tiles which were made within a short walk of our home in Stoke-on-Trent.

This was a week for exploring parts of Central Park we had not previously properly explored. On Thursday we spent a couple of hours in the northern part of the park, visiting Fort Clinton, the Conservatory Garden, the Huddlestone Arch, the North Woods, and several other parts off our regular beaten paths.

Central Park has so many delightful corners, several of which we have yet to visit together.

On Friday morning, we went to Grand Central Station, one of the most splendid buildings in the city, from which we travelled up the Hudson to the Bruderhof’s Mount Community.

It was the Plough Young Writers’ Weekend. Susannah was delivering a few talks and encouraged me to come with her. Although I did not participate in any of the sessions, I got to know several of the students during the meals and various leisure times.

The Bruderhof’s Mount Academy is a four-year high school next to the Hudson River, in an imposing building that was once a Redemptorist seminary. The Redemptorists had moved to the site from Baltimore, after losing too many of their number to tuberculosis. Seeing the building from the front, one could imagine it in a Wes Anderson movie (we had watched The Phoenician Scheme at the cinema with Hannah Long earlier in the week).

On the first evening, after the opening sessions, we gathered on the roof of the building for snacks and socialization.

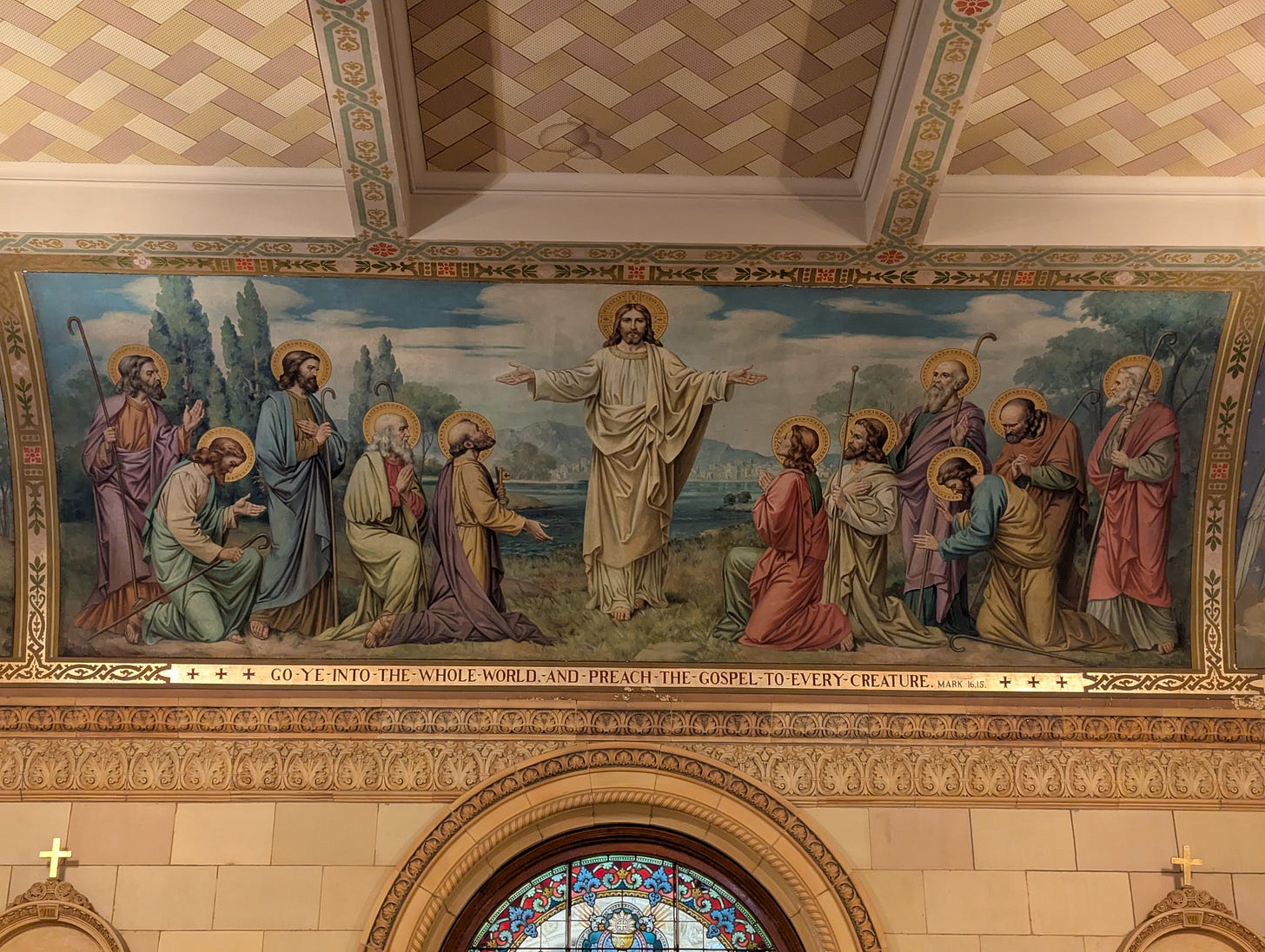

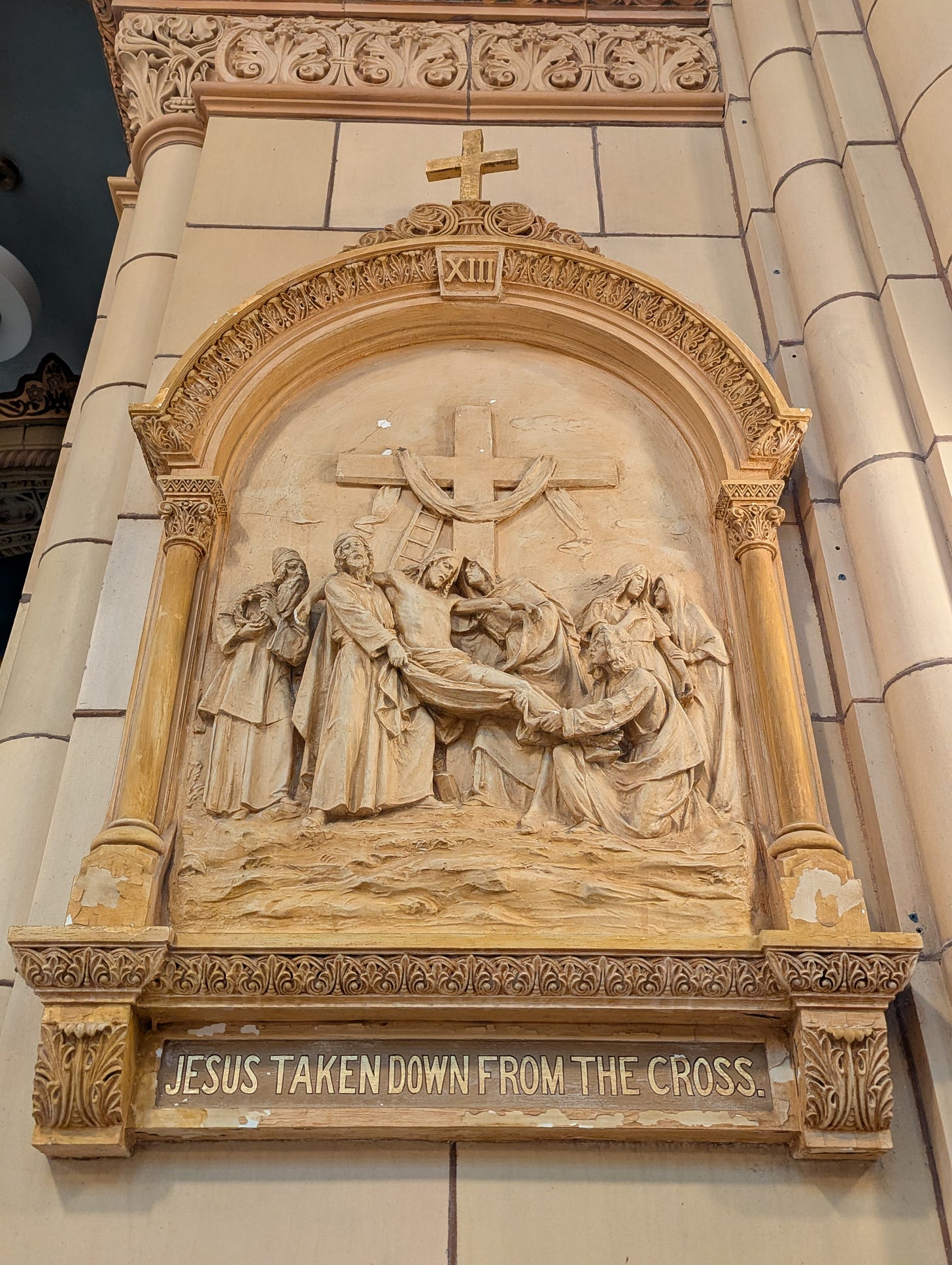

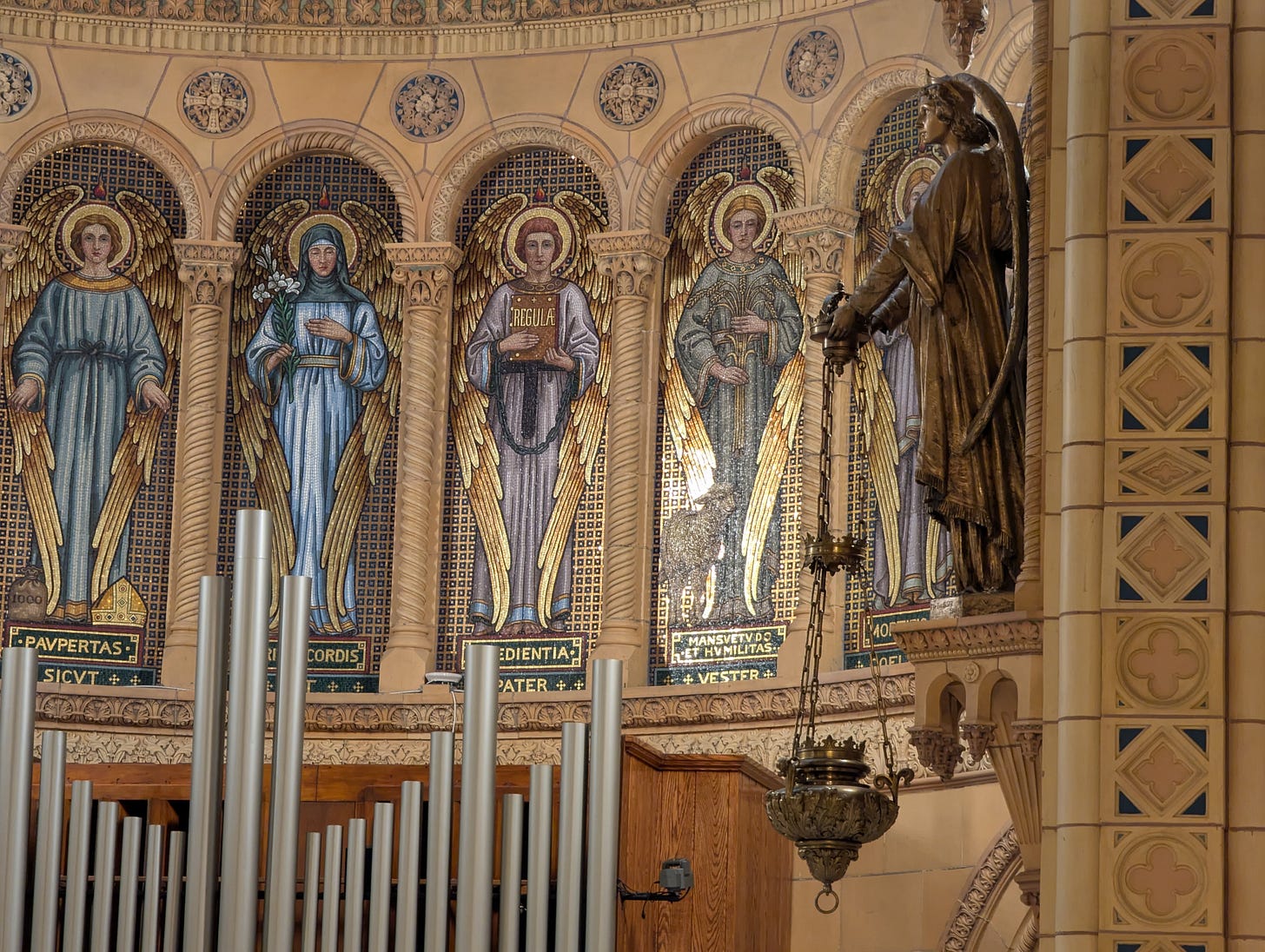

During our visit, we were treated to a tour of the building. The chapel is remarkable, with a domed glass window, mosaics of spiritual virtues, elegant stonework, and impressive paintings and stations of the cross.

On Saturday afternoon, we went to the Bruderhof’s nearby camping lodge, enjoying a barbecue, activities next to the lake, foosball, and lots of stimulating conversation. The young writers were a wonderful group, and it was a privilege to get to speak with several of them over the course of the weekend.

In the evening, we had more conversation down on the shore of the Hudson.

On Sunday morning, we joined the Mount Community for breakfast and worship, before returning to the city on the train. The whole train journey was taken up with further conversation with some of the attendees of the weekend.

It was my first visit to the Mount Community (the fifth Bruderhof community I have visited) and, over our brief stay, I was once again impressed by the witness of the Bruderhof’s life, by their commitment to lifelong education and the forging of wider bonds, and by their tremendous imagination, creativity, and good humour.

How to Write Something Much Better than a Hot Take

Susannah: The following is a tweaked version of the writing advice/handout I gave to the Young Writers (Young is defined by Plough as the Catholic Church defines it: there were some people there in their 30s) at the weekend up at the Mount. Keep your eyes open for the upcoming Plough Substack, which will include more such writing advice, as well as providing frameworks for how to pitch, how to self-edit, and thoughts, asides, and insights from our editors!

###

Say you’ve gotten an idea for a thinkpiece. You’ve seen something on Twitter or read something in WaPo. It’s made you Mad and given you a Big Idea about What’s Wrong With the World. Probably it’s the fault of Disembodiment or Disenchantment. It’s certainly traceable to the Lack of Thick Community and is probably traceable to Nominalism.

Sample: Young people aren’t going on dates any more. William of Ockham’s intellectual errors explain why.

Here’s what you should do. Write down your hot take, briefly, and then put it aside. Demote it from Pitch or Take to Topic. It is not yet a Pitch. And your Take may be correct, but you don’t know that yet. Hold it as a hypothesis, however half-baked it is, but hold it lightly.

And then ask yourself these questions. Write in response to them: names, phone numbers, addresses, and notes, paragraphs, other questions. These questions will not finish your piece for you. But, when you write in response to them, and collect the results of your research, they will generate the ingredients that you will need to write something that is actual magazine journalism and has the chance to be good.

Where is anything related to this physically happening? Can I go there?

How can I test my hypothesis? If I were wrong, how would I know?

What have some people who are wiser than me and who disagree with me and with each other said about this topic?

Who has expertise in this topic?

Who can I talk to who has been doing something practical related to this topic for more than three years?

What scenes - as in a play - would illustrate this topic?

What in my life makes me care about this topic?

What is the most vivid personal anecdote that you can tell that would explain that?

If I don’t have a vivid personal anecdote about this topic, who would? What is their anecdote?

What secrets related to this topic can I find out?

What statistics related to this topic can I track down?

What institutions related to this topic exist and how can I get involved with them? (infiltration, interview, business records.)

Who has written about something related to this topic 50 years ago? 100? 500? 2300?

What fiction or poetry has been written about this topic?

What are counterexamples to the problem this stood out to me about this topic?

What else is going on that might be a confounding factor: what affects this topic?

Who can I talk to who has experienced the dire consequences of this topic, or other aspects of this topic, firsthand?

What community can I visit where this topic is being suffered or countered? Who are the key people in that community?

What adventure or caper can I go on to explore this topic?

What historical parallels to this topic are there? Who are those people and what are those stories?

What are the Golden Nugget quotes from interviews or other texts related to this topic that I almost certainly will want to include?

Finally, for a Plough piece: How can what I have uncovered in this investigation help readers to live as though another life were possible?

Exercises:

1. Go through your piece or pitch. For each assertion that you make, think of a scene or conversation which would allow you to show that assertion being the case. Then go look for where those scenes or conversations would be, if they existed. Be open to being extremely surprised. Be open to finding that your Take was uninformed. Be open to the world being complicated. Be open to being wrong.

2. Read Joan Didion’s “Slouching Towards Bethlehem.” Identify in it the Cranky Hot Take she probably originally came up with. Then notice what she did with that. A crucial insight in your life as a writer is that having the same opinion about the hippies as Joan Didion does not make you Joan Didion. And in any case you would not want to be Joan Didion.

3. Read Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia, Michael Frayn’s Copenhagen, & Will Arbery’s Heroes of the Fourth Turning. Identify the Hot Take or Big Thinkpiece that each could have been. Notice how the ideas/themes from that Hot Take or Big Thinkpiece are made into scenes & characters & dialogue, and made more complicated.

‘Covenant’ Overload

Alastair: There are few terms with greater currency among Reformed theologians than ‘covenant’. The term principally names the gracious relationship that God established with humanity, the substance of which is seen in Christ, unified across the entire history of salvation, yet variously administered in different periods of history.

Filling out this concept of covenant in much Reformed theology, one may find reference to concepts such as the ‘covenant of works’ and the ‘covenant of redemption’. The covenant of works, as defined by chapter VII of the Westminster Confession of Faith, is a covenant ‘wherein life was promised to Adam; and in him to his posterity, upon condition of perfect and personal obedience.’ This covenant of works was broken in the Fall, yet the covenant of grace (which is generally what is referred to when covenant theologians speak of ‘the covenant’) is founded upon Christ’s fulfilment of the requirements of the covenant of works as the Second Man and Last Adam. Often referred to as his ‘active obedience’, Christ’s perfect keeping of the law—the covenant of works being seen in the moral requirements of the Ten Commandments (whether or not the Mosaic covenant is seen as a ‘republication’ of the covenant of works)—is imputed to his people, granting them righteous standing with God and eternal life.

Some go further, speaking of a ‘covenant of redemption’ that grounds God’s work of salvation in history. The covenant of redemption is understood as the eternal intra-Trinitarian agreement or plan that provides the basis for the covenant of grace. As such, it presents the covenant of grace (which some would identify with the covenant of redemption under a different aspect) as resting on the surest and firmest of grounds: God’s own eternal purpose within himself, determined before time began. God’s purpose is not contingent in its establishment upon created or historical events, circumstance, or persons. This offers the utmost assurance of the reliability of divine grace.

Besides speaking of the ‘covenant’ in the senses above, covenant theologians can speak of various historical ‘covenants’ (the Noahic covenant of Genesis 9, the Mosaic covenant established at Sinai, the Davidic covenant of 2 Samuel 7, etc.), foregrounding these in their account of the history of redemption. These are commonly understood as different administrations or dispensations of the one covenant of grace (although there are debates about whether the Mosaic covenant is a ‘republication’ of the covenant of works in some circles, for example). Prior to the advent of the Gospel, these dispensations foreshadowed and administered the grace of Christ.

Treating ‘covenant’ as a principle with which we have purchase upon the biblical witness is not peculiar to covenant theology. The very terms ‘Old Testament’ and ‘New Testament’, pervasively used by Christians of all stripes, use the principle of covenant to frame the material of Holy Scripture itself. Covenant theologians tend to take the concept further, privileging and foregrounding covenants more broadly (not just old and new) as a structuring device for their narration of the history of God’s dealings with humanity, developing the concept of the covenant of grace (as a sort of meta-covenant administered within various other covenants), and sometimes further concepts such as the covenant of works and covenant of redemption, and extensively deploying the concept and vocabulary of covenant to refer to the economy of grace within their lives and communities.

Beyond the architectonic importance that the concept it names enjoys in covenant theology, ‘covenant’ is among the most popular terms in many Reformed or Presbyterian circles. If you have ever seen ‘covenant’ in the name of a church or institution, or attached to some theory, publication, or movement, there is a considerable likelihood that the entity in question is Reformed or Presbyterian.

In Reformed theology, the concept of ‘covenant’ also implies an emphasis upon the continuity and unity of God’s gracious dealings with humanity across various historical dispensations. Especially in an American context, ‘covenant theology’ contrasts with ‘dispensationalism’, a position that has been widely held among evangelical and fundamentalist Baptists: dispensationalism holds to sharper divisions between eras of God’s dealings in history and between the people(s) of God under these different administrations. In addition, the term ‘covenant’ can be liberally deployed as a qualifier—’covenant children’, ‘covenant home’, ‘covenant family’, ‘covenant community’, etc.—to refer to the intergenerational, communal, and ecclesial form of the economy of grace. In contrast to most evangelicals, Reformed Christians tend to emphasize the way God’s grace is typically given through natural channels of communities and families. Reformed Christians will typically appeal to both these things—the continuity of God’s gracious dealings through history and the economy of that grace in the more communal context of faithful families and churches—to justify the baptism of the infants and young children of believing parents.

The term ‘covenant’ has been various defined and used among ‘covenant theologians’. For instance, O. Palmer Robertson, in his influential treatment of the subject, The Christ of the Covenants, defines covenant as ‘a bond in blood, sovereignly administered’. Such a definition does not cover all things referred to as ‘covenants’ (whether theological notions such as the covenant of redemption or more secular uses of the term in Scripture and elsewhere). Other biblical theologians have given attention to the parallels between Ancient Near Eastern suzerain treaty forms and things such as God’s covenant with Israel at Sinai.

In our current Theopolis podcast series on the book of Hebrews, we got into a discussion of the concept in the context of the use of the term in that epistle. Peter Leithart subsequently shared some thoughts on the subject, remarking on the fact that the term ‘covenant’ is fairly uncommon in the New Testament, with most occurrences being in the book of Hebrews and there largely in chapters 8-10. Without simply dismissing later theological uses of the term, Leithart encourages us to reflect upon the fact that New Testament teaching largely operates without explicit reference to the covenant, suggesting that ‘covenant’ may not be ‘quite the all-encompassing concept that Reformed folk think it is’.

The use of the term ‘covenant’ in Hebrews largely relates to the contrast between two covenants—the old covenant that was broken and the ‘better covenant’ brought in by Christ. It arguably does not speak of the ‘covenant of grace’ as such, but of a historical shift between two specific covenant orders.

Of course, it is important to bear in mind here, as my friend John Barach notes, that theologians will often develop stipulated meanings for terms adopted from Scripture, which serve important purposes within their theological frameworks, but whose meanings diverge from their scriptural uses. In such instances it is important to register the divergence, but we do not need to jettison the stipulated theological senses on account of differing biblical usage. That Scripture does not use the term ‘covenant’ in the way that covenant theologians do does not render covenant theologians’ use of the terminology illegitimate.

Nonetheless, it is often healthy to take such familiar terms, compare them to biblical usage, and consider whether they have limitations. In the case of the term ‘covenant’, we might perform the experiment of substituting it with the term ‘relationship’. When grounded by specific referents—‘the relationship established at Sinai’, ‘the new relationship brought in by Christ’, etc.—such a term would be quite meaningful. Likewise, one of the strengths of covenant theology is its recognition that God’s dealings with humanity across history are part of a unified ‘relationship’.

However, as covenant theology has leaned into the latter sense—of the continuity of a single ‘covenant of grace’ as ‘the covenant’—it has been tempted, not least on account of the spatializing tendencies of systemic theology in the modern period, to veer in the direction of less grounded and historical accounts. A theological emphasis upon the unity of the covenant across history has functioned theologically to dampen expressions of its historical development. Yes, such approaches suggest, there are different dispensations of the covenant in history, but there is one underlying covenant of grace and, while redemption is accomplished in history, behind its varying administrations, the underlying covenant is unchanging. Concern for a sort of enduring meta-covenant can obscure a historical narrative for which covenant is arguably not present during certain critical periods (e.g. from creation until Noah) and where much narrative development does not seem to be an outworking of it as a theme.

While many Reformed biblical theologians have done sterling work in recovering the importance of the continuity of God’s dealings with humanity as that of a developing reality through time rather than of a single unchanging reality above time, even when trying to do justice to the history of redemption, the master concept of ‘covenant’ has often encouraged a drift in the latter direction.

Seeing the various covenants of history in terms of the one covenant of grace, which in turn is understood largely in terms of the principle of redemption, also tends to obscure different thematic throughlines. As James Jordan has observed, the entirety of Scripture could be read with the theme of maturation being dominant or perhaps holy war, moving from the rebellion of the serpent to the defeat of the dragon. Considering covenants individually, one could argue, for instance, that some of them represent movement into fuller sonship more than they do redemption, even if the work of redemption is presupposed by, a prerequisite for, or advanced in some manner by them.

I have increasingly tended towards accounts of the development of God’s acts in history that foreground the movement of creation towards glorious consummation as humanity created in the image of God is raised to its full stature in Christ. Hugely important though and integral though it is, redemption is not the most dominant note here: the dominant note is the Word taking flesh, in the fullness of its Christological, anthropological, ecclesial, and cosmic import.

Thinking of ‘the covenant’ as such has encouraged thinner and narrower understandings. Substituting the term ‘relationship’ for ‘covenant’ and speaking about ‘the relationship’ in the way that covenant theology often speaks of ‘the covenant’ as a single transhistorical reality, it would be clear that, while perhaps a useful term with which to gesture towards the whole, it is far too vague to be loadbearing. It either needs to be concretized—in a narrative, for instance—or, alternatively, it needs to be more specified as a meta-concept.

The loadbearing capacity of the concept ‘the covenant’ can be sought in different ways. The more general concept could be theologically narrowed. For instance, one could say that ‘covenant’ is not merely a relationship, but a vowed bond sovereignly and unilaterally established by God, with ‘the covenant’ finding its substance in Christ. While not altogether misguided, the practical effect of this is to thin out the concept considerably. The narrowing of the concept comes at the expense of the fuller reality encountered in the biblical narrative.

Alternatively, ‘the covenant’ could serve as convenient shorthand for the story of God’s dealings with humanity across the entirety of history, from its origin in his eternal purpose until the consummation of this in the new heavens and new earth. In such an approach, ‘the covenant’ is doing considerably less loadbearing as a master concept, mostly serving as a convenient blanket term to cover various other concepts and narrative realities that are doing the bulk of the heavy-lifting.

Illustrating the difference, a son could meaningfully talk about his ‘relationship’ with his father, in a way that comprehended everything from the period of his early infancy to that of his adulthood where he acted as the recognized representative of his father. That relationship is appropriately considered as a single and unified thing. However, were one to lean heavily upon an underlying meta-relationship that is variously expressed in different periods of life, the significance of the growth could easily be underplayed. The single, unified relationship between the son and his father is better considered in terms of a unity through time, as the unity of a narrative (as we might speak of a personal identity), rather than of a sort of core meta-relational reality that is unchanged through history.

Covenant terminology is concentrated in places in Scripture where God is either establishing or promising a new form of relationship with his people or in places where the people are being condemned for breach of that relationship. As a concept, it tends to foreground the formal and legal dimensions of God’s relationship with his people. The forensic concerns of much historic Reformed theology have naturally made such a framework attractive. However, where ‘covenant’ is highly privileged as a conceptual framework, it will subtly—and sometimes not so subtly—pull our understanding of our relationship with God in directions that overemphasize legal dimensions.

Scott Swain helpfully observes the presence of so-called ‘covenant formulae’ at critical junctures within the New Testament:

For this is the covenant that I will make with the house of Israel after those days, declares the Lord: I will put my laws into their minds, and write them on their hearts, and I will be their God, and they shall be my people. Hebrews 8:10 (citing Jeremiah 31:33)

And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, “Behold, the dwelling place of God is with man. He will dwell with them, and they will be his people, and God himself will be with them as their God.” Revelation 21:3

The one who conquers will have this heritage, and I will be his God and he will be my son. Revelation 21:7

Such statements are not inappropriately called ‘covenant formulae’, not least as they generally illustrate God’s self-binding vowed commitment to his people in a formal and defined relationship. However, it is important to notice the way that such statements can gesture towards thicker and more prominent motifs such as sonship, divine (in)dwelling, marriage, communion, kingship, and the like.

To illustrate some of my concerns here, it might be helpful to consider marriage, which is, by many definitions, a form of covenant. A marriage is a legal and formal union, typically entered into through a covenant ceremony, with witnessed vows, and official binding documents. This reality of marriage is most prominently experienced in a wedding and the other formalities surrounding the official registering of a marriage. It might also come to the foreground in a situation where the marriage has broken down and the couple are divorcing.

The entire reality of a marriage can be viewed from the vantage point of this understanding. A wedding is not merely the first episode in a marriage, but a perspective from which the whole marriage can be seen. Every day and in every act one relates to one’s spouse, one could see oneself as living out one’s marriage vows. However, while such a perspective may be important, if it were accented or prioritized to the exclusion of others, it would prove quite limiting and distorting. The relationship between a husband and wife typically both precedes and greatly exceeds its formal and legal character as a marriage. Were the formal and legal character always foregrounded, one can imagine that something might have gone awry. The actual living out of married life mostly does not have the felt character of fulfilling mutual vows, but of enjoying and growing in a shared life. The vows may ground and adumbrate this, but ‘vow-keeping’ does not best characterize its content and animating reality. Marital vows must be kept, but most of the time they are kept indirectly, simply as one devotes oneself to one’s spouse, rather than as one tries to keep one’s vows.

Were a couple frequently to appeal to their wedding vows in their marriage, one might wonder whether there was a lurking insecurity or failure of love. Even though one could argue that the wedding vows are foundational, much of the reality is found in the superstructure that is confidently built upon them. One does not always have to unearth the foundations to find a secure base to rest upon. One should generally be confident in both the strengths of the foundations and that which has already been built upon them.

Just as the formal, legal, and vowed character of a marriage can offer a perspective upon the whole reality, while narrowing our sense of the reality if not routinely accompanied by other perspectives, so ‘covenant’ is most valuable when employed as one highly revelatory vantage point among others. The problems arise when it is treated as the controlling perspective upon everything.

Returning to the covenant formulae, when God declares ‘I will be his God and he will be my son’, for instance, the recipient of this word can appropriately be assured that their standing with God and adopted sonship ultimately rests upon something truly secure—upon ‘covenant’. However, important though the continued assurance of legal standing with God is, the reality of sonship will mostly be known more directly in things such as fellowship and communion, blessing, inheritance, and empowerment without the constant conceptual intermediation of covenant.

We should also consider the way that the biblical narrative presents God’s gracious relationship with people as something that can precede and exceed ‘covenant’. God calls and makes great promises to Abram before he ever establishes his covenant with him. One could argue that, much as the story of a couple’s love and life together typically precedes their entrance into the covenant bond of marriage, with marriage serving to ground, give form to, and extend their existing love and commitment, so covenant arises from and serves a deeper divine purpose of love, a purpose that may not itself be best described as ‘covenantal’ in character. Further, although Gentiles were formerly ‘strangers to the covenants’ (Ephesians 2:12), this does not mean that God had no gracious dealings with them, and did not already love them. Indeed, it was precisely because “God so loved” them that he did what was necessary to bring them into his New Covenant.

Reformed theology’s preoccupation with forensic categories and desire for clear assurance of standing with God represent concerns to which ‘covenant’ legitimately and powerfully answers. However, were we to consider the relationship God has formed with us more expansively, many other blessings might come into view and we might also be less susceptible to various distortions of understanding. Reducing the loadbearing of the category of ‘covenant’ may be helpful for many Reformed people in doing this.

Remarks on ‘Ecclesiocentrism’

‘Ecclesiocentrism’ is a term I have seen used in various ways. It responds in part to visions of Christian social transformation that practically or theoretical put political and social reconstruction and conflict in central position, marginalizing or subordinating the church. In other frameworks ecclesiocentrism responds to, the church is presented as one institution alongside others—family, state, business, etc. Now, there is something to such frameworks, inasmuch as they can address the dangers of clericalism and ministers overreaching their bounds.

However, there is something distinctive about the Church, as the sanctuary and the symbol of the kingdom. I believe it is quite possible—and important—to articulate this with two kingdoms and visible/invisible church distinctions. Understood in such a manner, the Church desacralizes present-age politics. The Church provides an inassimilable presence amidst the kingdoms of the world, testifying to a greater and higher kingdom. It is in distinctive local and regional forms, with ‘present-age’ ecclesial polities, yet symbolizes and relates to a reality that exceeds them.

Ecclesiocentrism suggests that the Church itself is not politically neutral or insipid. It represents a peoplehood, a polity, and an authority. It also represents these in ‘present-age’ ways that herald a coming reality. These temporal dimensions are key for the ‘-centrism’.

Ecclesiocentrism tests and relativizes ‘present-age’ polities (including the present-age structures of churches themselves). But it also informs (without dictating), blesses (without sacralizing), and renews (without eternalizing) them.

Historically, the Church has powerfully formed societies, peoples, and nations (e.g. Bijan Omrani’s recent book discusses the way the Church served to create England). Ecclesiocentrism, however, does not refer to a clericalist order, but to a society that finds the source of its life in the sanctuary, and its destiny in the age to come.

A key effect of this is to humble the pretentions of various kingdoms that might present their own implicit eschatologies or visions of true catholicity. The Church unsettles these by its faithful existence. One might think here of the description of Christian’s presence amidst the kingdoms of this present age in Mathetes’ Epistle to Diognetus.

Now, such ecclesiocentrism is quite compatible with the pursuit of Christian civilization. Indeed, it would encourage it, while resisting all attempts to identify the higher order it symbolizes with any present-age polity. Even in a Christian polity, we remain sojourners in part.

This is important for addressing the dangers that arise from people who put too many of their chips in the success of Christian civilization. Christian civilization may be highly worthwhile, yet prioritizing it over its vital spiritual source can lead to many damaging consequences.

The Church symbolizes and relates to something that surpasses and exceeds the kingdoms of this present age, so is not in straightforward competition with them, as two political entities of the same kind and on the same plane may be. However, as the stone cut without hands that shatters the empires and becomes a mountain filling the earth in Daniel 2, the kingdom of Christ is not an apolitical entity. Christian activity flows from a higher political reality and practices a different politics, but not political quietism.

And, just as ecclesiocentrism resists sacralization of ‘present-age’ politics, by stressing the distinctive nature of the eschatological, heavenly, and spiritual order to which the Church relates, it can also resist the confusions that lead to clericalism.

Some forms of ecclesiocentrism need better distinctions between visible and invisible Church, two kingdoms, and the present age and that which is to come. The universal kingdom of Christ the Church symbolizes needs to be clearly distinguished from a universal clerical kingdom. Church government is also a polity of this present passing age. Yet the Church itself will endure, into the world of the new heavens and new earth that it already figures forth in part in this age.

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ Mere Fidelity 2.0 is well into its swing now. Derek, James Wood, and I were joined by Professor John Bolt to discuss Herman Bavinck and the Reformed Ethics translation project. We had a great episode with Jason Blakely, who considered the work of the late Alasdair MacIntyre with Brad East, Derek, and me. Andrew and I also recorded a show with just the two of us, on the deep weird of the book of Daniel.

❧ The Theopolis podcast series on Hebrews continues, with Jesus, High Priest of a Better Covenant (Hebrews 8:1-7) and What is a Covenant? (Hebrews 8:6-13).

❧ I concluded my Theopolis series on time.

James Jordan, Time, and Wisdom

❧ I have produced the following video of a past Argosy reflection.

Eight Lessons from the Psalms in the Book of Hebrews

Upcoming Events

❧ Much of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

❧ This year’s Theopolis Ministry Conference is entitled ‘Singing the City of God’ and is on the subject of music in the life of the Church. You can find out more about it here.

❧ Alastair will be leading an online workshop for Theopolis in October and November on the subject of Pentecost. It is only $150 for ten hours of classes.

❧ At the end of September and beginning of October, Alastair will have events in Langley, BC, in Columbia, SC, in Birmingham, AL, and in Franklin, TN. Watch this space!

❧ At the end of October and beginning of November, we will be in Marseille in the South of France.

Much love,

Alastair and Susannah

That writing advice is greatly appreciated. I've felt for a while that I'm at a standstill in my own development as a writer; your suggestions are, I'm sure, going to make a huge difference to me. Thank you very much!

I look forward to hearing more about the Plough Substack as well.

Thank you for sharing your writing advice.