Susannah: I’m inserting my update before Alastair’s, because while his Cambridge photos are wonderful, my Venice photos get pride of place.

The friends and family and extended-universe wellwishers who are (I assume) our subscribers already probably know about my somewhat inexcusable annual trip to Venice for Carnevale. I went first in 2020, and the last two days were shut down by COVID; Alastair’s and my couplehood dated from just a couple of days after that, and so returning to Venice reminds me of the magic of the new life that started with our engagement and marriage—sometimes it does feel as though I left New York in early February of 2020 and then the whole world became reenchanted—both in a horrible way because of the pandemic and lockdowns, and in a wonderful way because of Couplehood. This is always the thing that you think is going to happen on a vacation: you think you’re going to slip into another world or be caught up in a sort of magical-realist spy plot or … something; falling in love, and then marrying, is that something.

So I went back to Venice, and spent 16 days there and in Trieste, and rather than give you a blow-by-blow I will just add a ton of pictures.

The first thing you notice about Venice is Venice. It is the city itself that is the wonder, that you have to figure out: how does this work? How could what I am seeing possibly be? How can it be this beautiful, but also, how does it possibly happen?

On a practical level, you simply can’t just throw up your hands and get an Uber as you could elsewhere: you are on your own legs and/or on other people’s boats, and you have to organize how to get around. And your phone probably will have virtually no signal, which seems only appropriate. When it does have signal, your precise location on a Google map will always be a bit of a gamble: the dot that is you will swoop all over the sestiere trying to guess where you are, and never really come to a definitive conclusion, and differences in feet and inches matter, because if you go down one eighteen-inch-wide passageway you will get to San Marco whereas if you go down the eighteen-inch-wide passageway just a few inches to its left, you will be lost in a warren of such alleys and sotoportegi.

The second thing you notice of course, around Carnevale, is the people.

And that’s before you actually find your own friend group. I was staying in an AirBnB with five other women, friends from New York, which was a lot of fun but by the end of the time the apartment had become an absolute chaos of backstage grownup theater kid makeup and costuming ephemera. We’ve all to some degree learned to sew in order to make or tailor or reinvent costumes, and while we’d gotten most of our making done in the months leading up to Carnevale, there are always last minute adjustments to make.

I’d used some scrap pieces of silk damask that I’d bought last year from Benevento, a wonderful hundred and fifty year old fabric store on Strada Nuova, to make little bags that work with most costumes to give to Carnevale friends.

These were really simple projects that I used to teach myself how to use my new sewing machine, how to work with fabric like that, which is a bit tricky, and how to design, as I didn’t use a pattern; distributing these was a lot of fun, though nearly everyone I gave one too was a better seamstress than I am; Carnevale is very much a gift economy, as all the skills of costuming and all the social niceties and all the tips for doing this very very inexpensively and all the tricks of existing in Venice, not to mention all the invitations and so on, are not things one can teach oneself; there’s very much a “pay it forward” attitude, which has kept the particular friend group that does the private parties going since 1979 when the custom of Commedia dell’Arte flavored Carnevale was renewed.

It had been a feature of Venetian life since 1162, reaching its peak in the 18th century before being banned under the Habsburgs in 1797, in part because masks were seen as politically dangerous, which they honestly probably were. Though periodic small private attempts were made throughout the 19th century to revive Carnevale, it was not until 1979 that a very energetic and passionate group of friends succeeded in doing so, and then the City threw its weight behind the revival.

The classic Carnevale costume “era” is early 18th century, and there is a distinct Commedia dell’Arte flavor to the costumes and the masks: each mask shape is linked to one of the stock characters in Commedia dell’Arte, though the most classic shapes are still the Bauta, traditionally white and worn with a tricorn, and the Moretta, traditionally black; the Moretta is also called the Muta, because you hold it on by keeping a button attached to the inner surface between your teeth, making it impossible to talk.

It is always a delight to see Carnevale folk; some of them are old friends now, people whom I’ve met each year and sometimes in New York or elsewhere at different times of the year. They tend to converge at Florian’s, on their way to one or other party.

Finally, there are the parties themselves, culminating in the Tuesday evening final night; this year, the theme for that was Vivaldi, with bautas and tricorns optional but encouraged.

There was a Clown Dinner, with various Clown Games as activities, organized by one of my friends: another mutual friend said “Oh well actually there’s this family of clowns who are here who are friends of mine, can they come?” and of course they could, so we got to hang out with the Morgans, who are indeed a family of clowns and acrobats who all live together in a giant blue castle in Laurel Canyon; the patriarch, Gary Morgan, whose parents were in Vaudeville, came over and we had a lovely chat after he learned that my father was in the business; I cannot tell you how much I want to introduce David Black to this man. Any of you who know my dad will know why this is a friendship that needs to happen.

It was at this point that I decided I had to reread Susannah Clarke’s novel Piranesi, for reasons which are if you have read the novel very obvious. And if you haven’t, no spoilers.

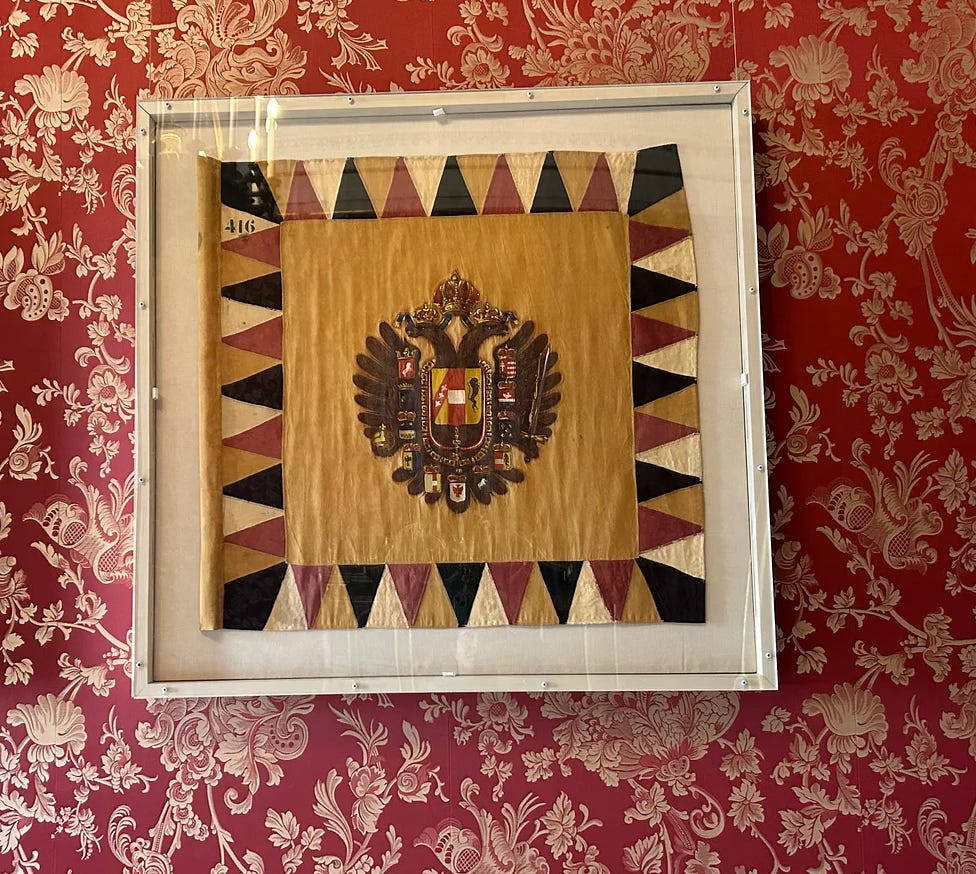

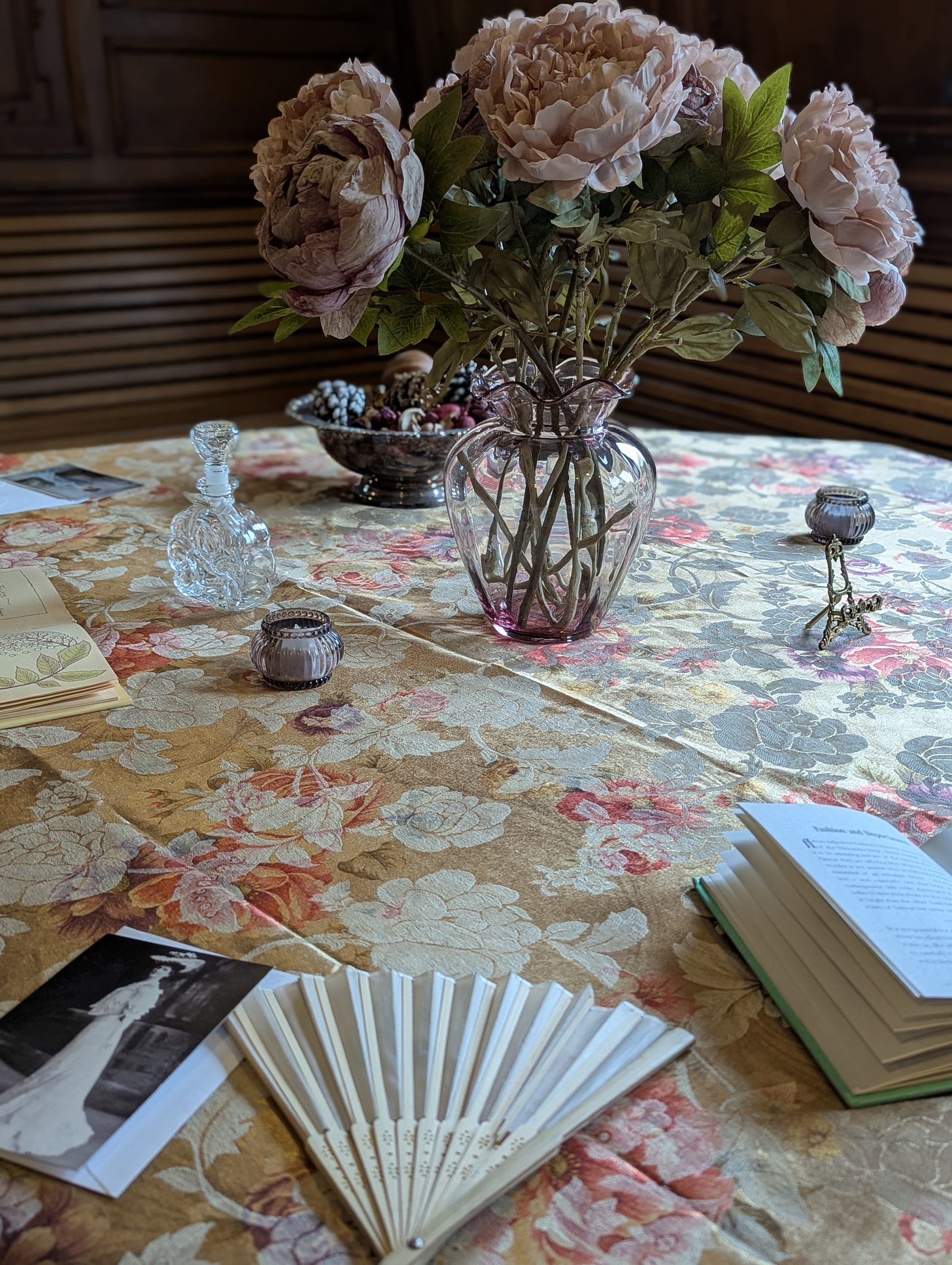

Part of the fun of the parties is seeing the interiors of the palazzi that they’re held in, seeing these rooms used as they ought to be used, as they were originally used. But we also, this year, wanted to do a bit more Museum-ing, and so went to the Palazzo Reale, the Royal Palace, on the opposite side of the Piazza San Marco to the Palazzo Ducale, the Doge’s Palace, which Alastair and I had visited last year.

Nowhere in Venice is the sense of poignancy and pain at the lost Republic so present as here. The huge complex of buildings, having been begun in 1537, was originally of course not a palace for a king or emperor: there were no such things in Venice. Rather they were public buildings: a library, offices and residences for the procurators who oversaw the government of the different districts of the city, and so on. It was Napoleon—you probably have the basic outline of this story—who brought the Republic low; she fell to his armies in 1797. He decreed that, as he was now emperor of (inter alia) Venice, it would be most appropriate for the buildings to be converted into the palace of an emperor. That lasted from 1807-1814, with the remodeling being completed several months before Napoleon’s (first) defeat, and it’s not clear that he ever actually slept in the place before he was shipped off to Elba, though he left his blue and gold and bees all over it; I do like them a great deal.

After he was (finally) dispatched after Waterloo to St. Helena and the horsetrading of the Congress of Vienna sorted itself out, Venice was given to the Habsburgs—more specifically to Francis I in his aspect of King of Lombardy-Venetia (which was, much to the surprise of the Lombards and the Venetians, apparently a thing one could be). They lasted, with Venice a very truculent part of the Austrian and then the Austro-Hungarian Empire, till 1866, when in the Third Italian War of Independence, Venice was incorporated into the recently invented Kingdom of Italy, which meant that the building was the home of Victor Emmanuel II of the House of Savoy. After the First World War, it became offices of the City of Venice, now understood as the capital of the Veneto region in the nation-state called Italy.

It’s now been restored, with different bits reflecting different eras of that past, and it’s a very weird, though beautiful, experience when you’ve seen the proud, secret, sinister Palazzo Ducale to see this chocolate box of a royal and imperial residence.

I also visited a museum dedicated to Leonardo da Vinci’s machines, and the Museum of the Palazzo Grimani, the home of a family of doges and dignitaries from the 16th century on which was having a special exhibit dedicated to Cabinets of Curiosities, and the Maritime Museum, which seemed to be more or less the municipal collection of model ships plus several donated and very personal collections of maritime related ephemera, and which dedicated a frankly puzzling amount of space to the close relationship between the Venetian and Norwegian navies over the course of the centuries, and … many other things.

The rest—well, it’s miscellany. The life of Venice.

And then I went to Duino and got what turned out to be COVID, so I just kind of languished for several days and read an Umberto Eco novel, and then came home. Getting COVID just seems so … cringe, at this point. Passé. But it was very mild and only lasted two days and I’m sure the Adriatic air helped. I thought it was a much milder case of the same flu I had in December. But no, it was our old enemy, the Coronavirus, as annoying and disruptive as Napoleon himself during the Hundred Days, and calling up a similar sense of “Are we doing this again? I thought we’d dealt with you already.”

Alastair: Writing this, less than three weeks after our last post was published, I am slightly surprising to discover that so little time has passed. The past weeks have been filled with work and other activities. Once again, we have both been on the road for much of the time. Susannah was in Venice for the start of it (see above), we spent a few days in Cambridge, and I also visited Belfast last week.

While Susannah was in Venice, I mostly had a regular writing and teaching routine. I joined my parents for pancakes on Shrove Tuesday, but largely worked at home. Before Susannah returned, my sister-in-law and nephew visited me and my parents for a day. We shared a meal at Toby Carvery. I had scheduled a local book group discussion of Josef Pieper’s Leisure: The Basis of Culture with a friend, but a couple of people who had hoped to join us did not make it, so we postponed the discussion and talked about other things instead.

Susannah was arriving back that day—Monday 10th—but, when she did, discovered that the fever that she had had a few days prior had actually been COVID. As we had quarantined from each other, I travelled down to Cambridge as planned early the next morning, while Susannah decided to wait out the full period of possible contagiousness.

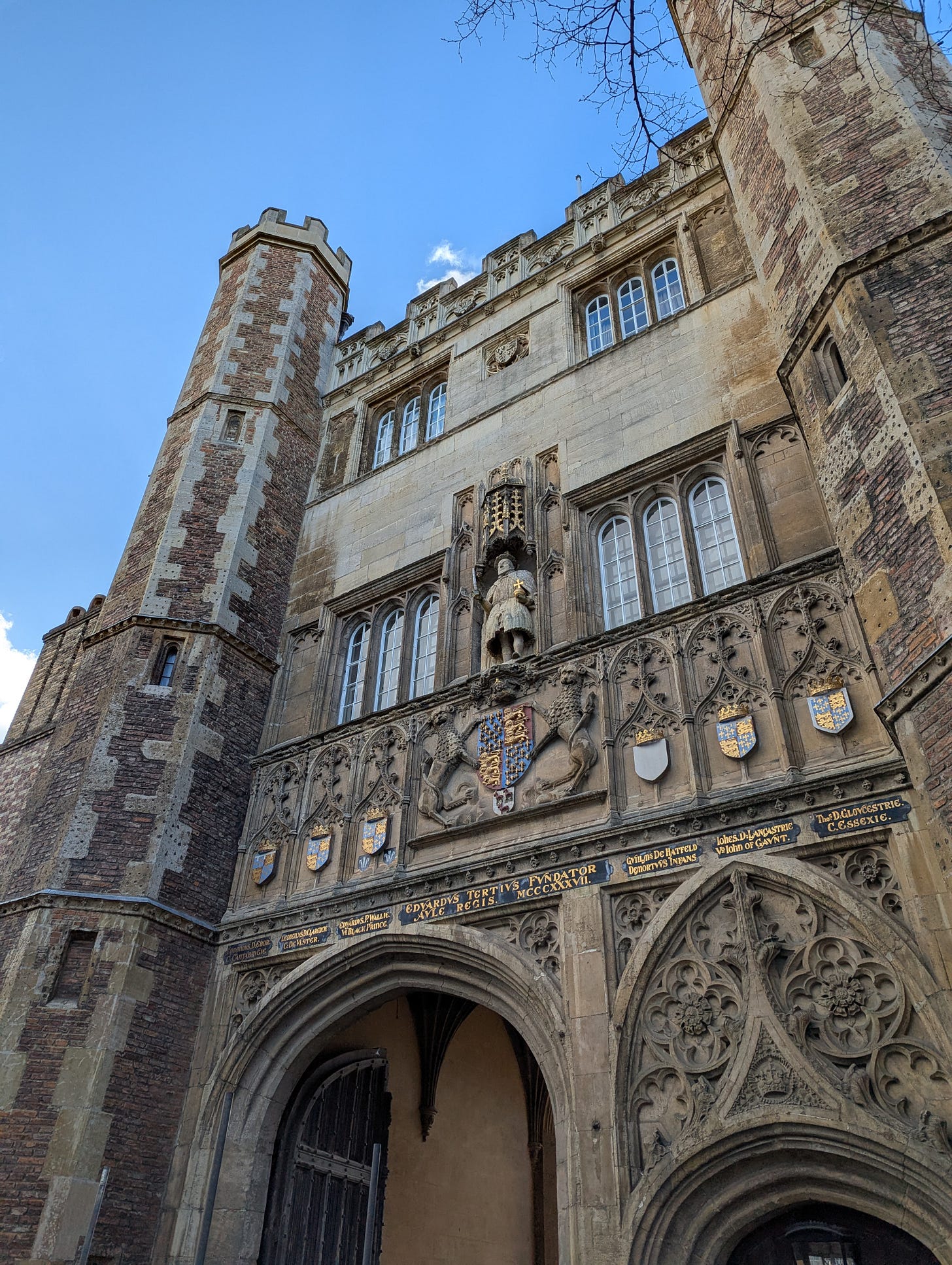

Cambridge has always been one of my favourite places. This time, the enjoyment of visiting was increased by the chance to spend time with many friends and acquaintances—we had literally about a dozen encounters with people we had not expected to see there! Among several others, as I was crossing a road on the way into the town on the Tuesday, an American acquaintance who is finishing a PhD on the book of Hebrews and happened to be stopped at the lights on his bicycle called my name and we arranged to have a coffee.

We stayed at Tyndale House. Although we have several friends who are scholars associated with it, it was our first time visiting the place. Tyndale House is an important centre for biblical research, with a world-class community of scholars. Many of you may be familiar with people like Peter Williams, and with my Theopolis friend and colleague James Bejon, who is also associated with Tyndale. During our stay, we had the privilege of getting to know some more of the scholars and workers at Tyndale and hearing about the exciting developments and projects going on there. If you would like to find out more about the work going on at Tyndale, you might enjoy listening to their podcast or consider signing up for their magazine, which Peter Williams aptly described as a sort of Christian National Geographic.

After arriving, I went into town, where I briefly looked around and then worked for a few hours, before returning to do some more reading in preparation for the classes I was teaching in the next few days.

Our visit to Cambridge had been planned, in large measure, around our friend Esther Meek, who was over from America. We had met up with Esther, a Christian philosopher, in NYC a year and a half ago, during which time we had discussed the idea of us spending some time together on the other side of the Atlantic. She had a series of talks that she was giving in Cambridge over the week, but had a day beforehand to explore some of the area.

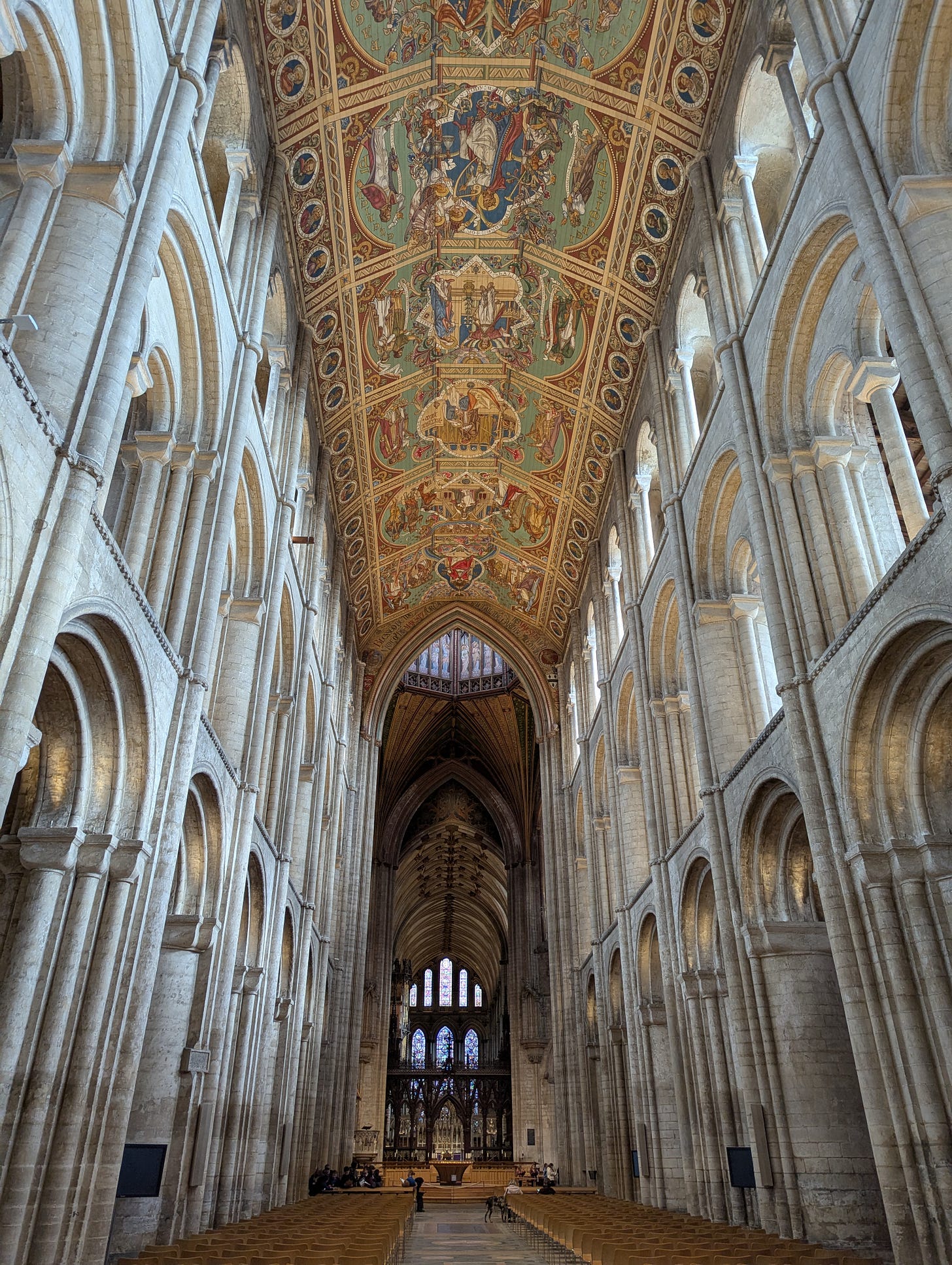

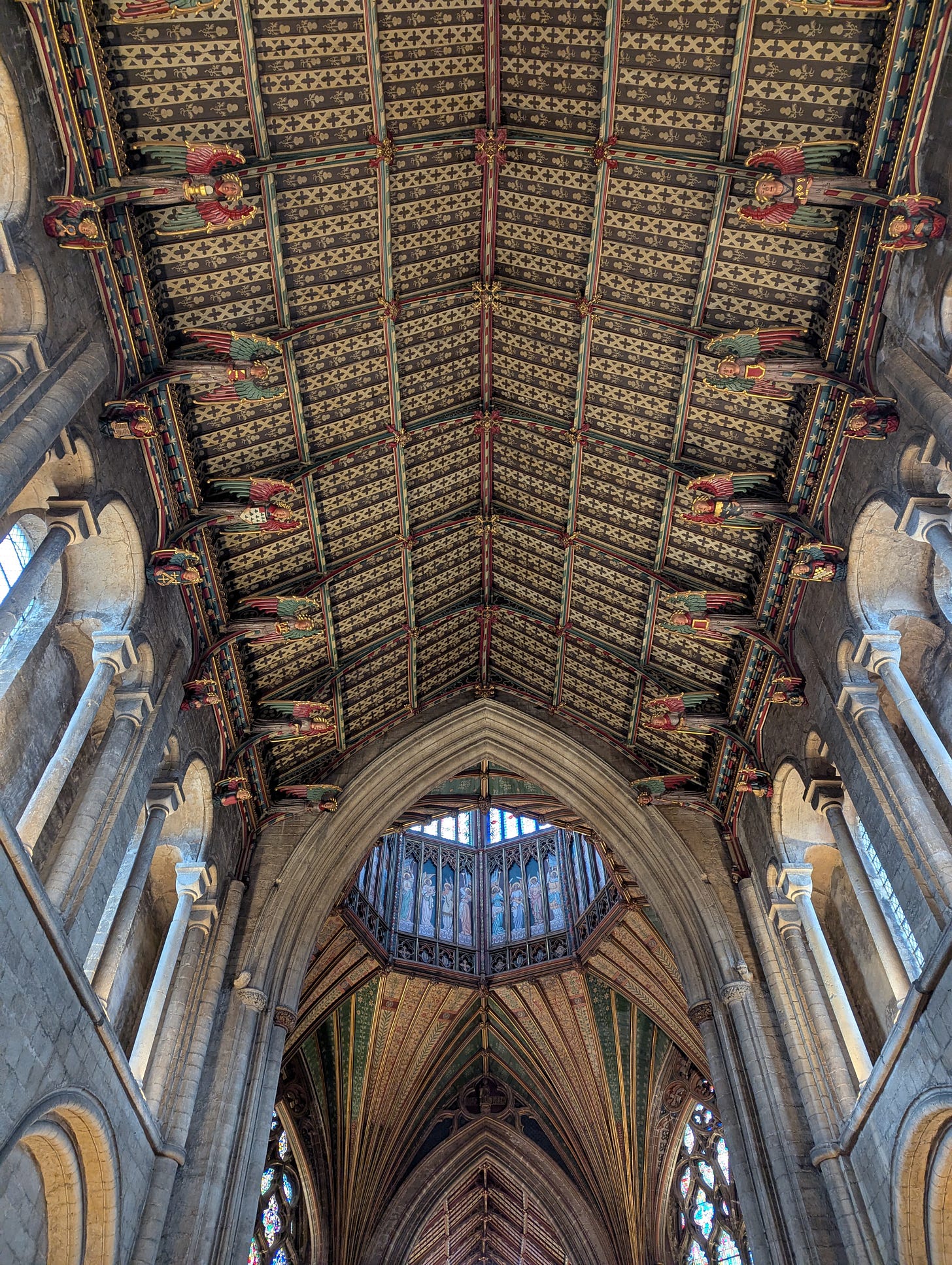

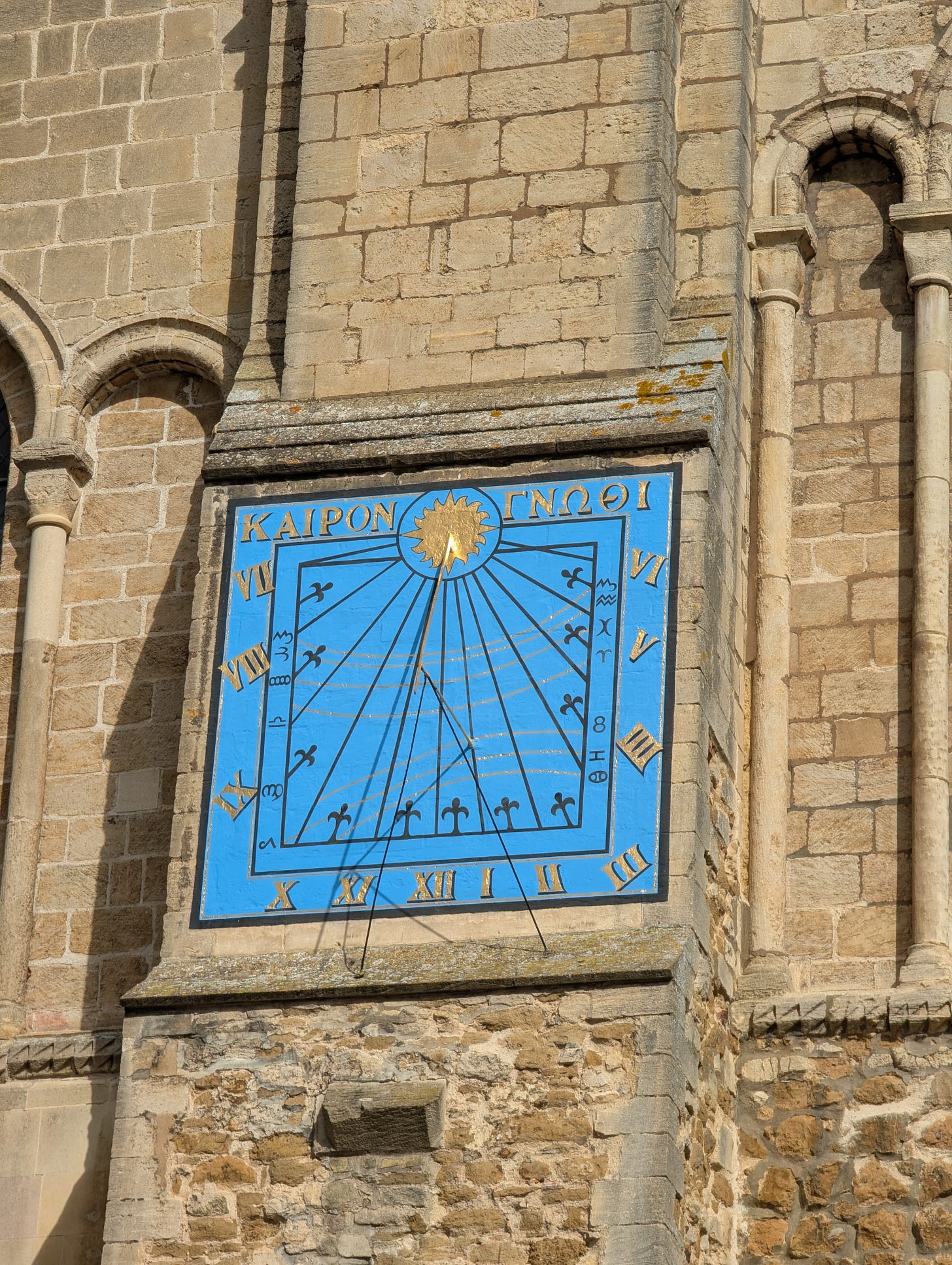

Although we were both disappointed that Susannah was not there to spend the day with us, we decided to go ahead and spend it in Ely, a delightful cathedral city near to Cambridge, with around 20,000 inhabitants (it is one of the ten smallest cities by population in the UK).

Ely was originally built on an island, the highest land in the Fens. After the Fens were drained, it ceased to be an island. Besides its cathedral—one of the finest in the country, by my judgment—Ely is famous as the place that Oliver Cromwell called home from 1636 to 1646.

We arrived at the cathedral just as some children from a local school were about to begin a musical performance, so we walked around the cathedral and the surrounding buildings first. The area was exceedingly wealthy during the medieval period, with its monastery being one of the richest in England. There are several beautiful medieval buildings in the vicinity of the cathedral.

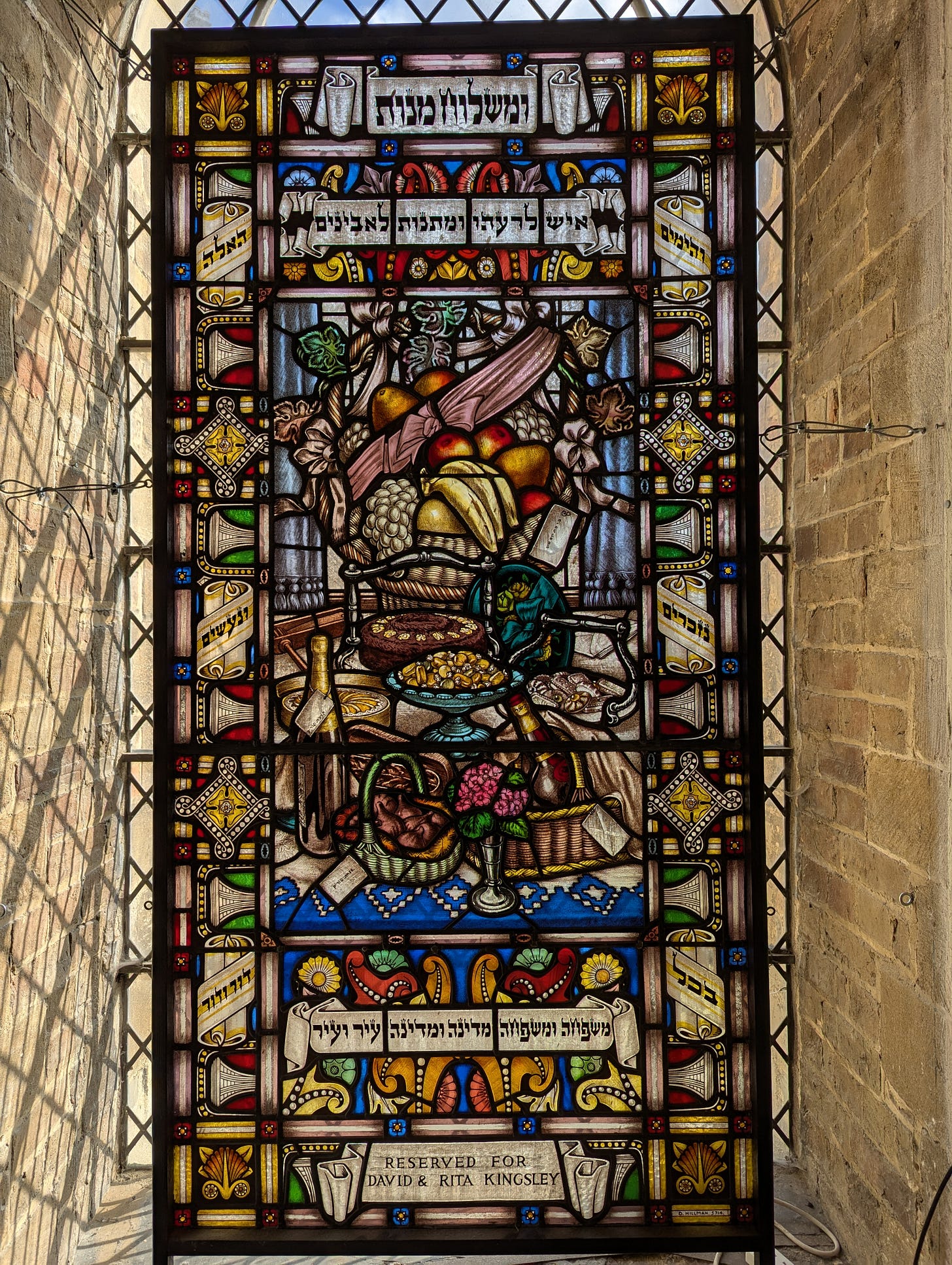

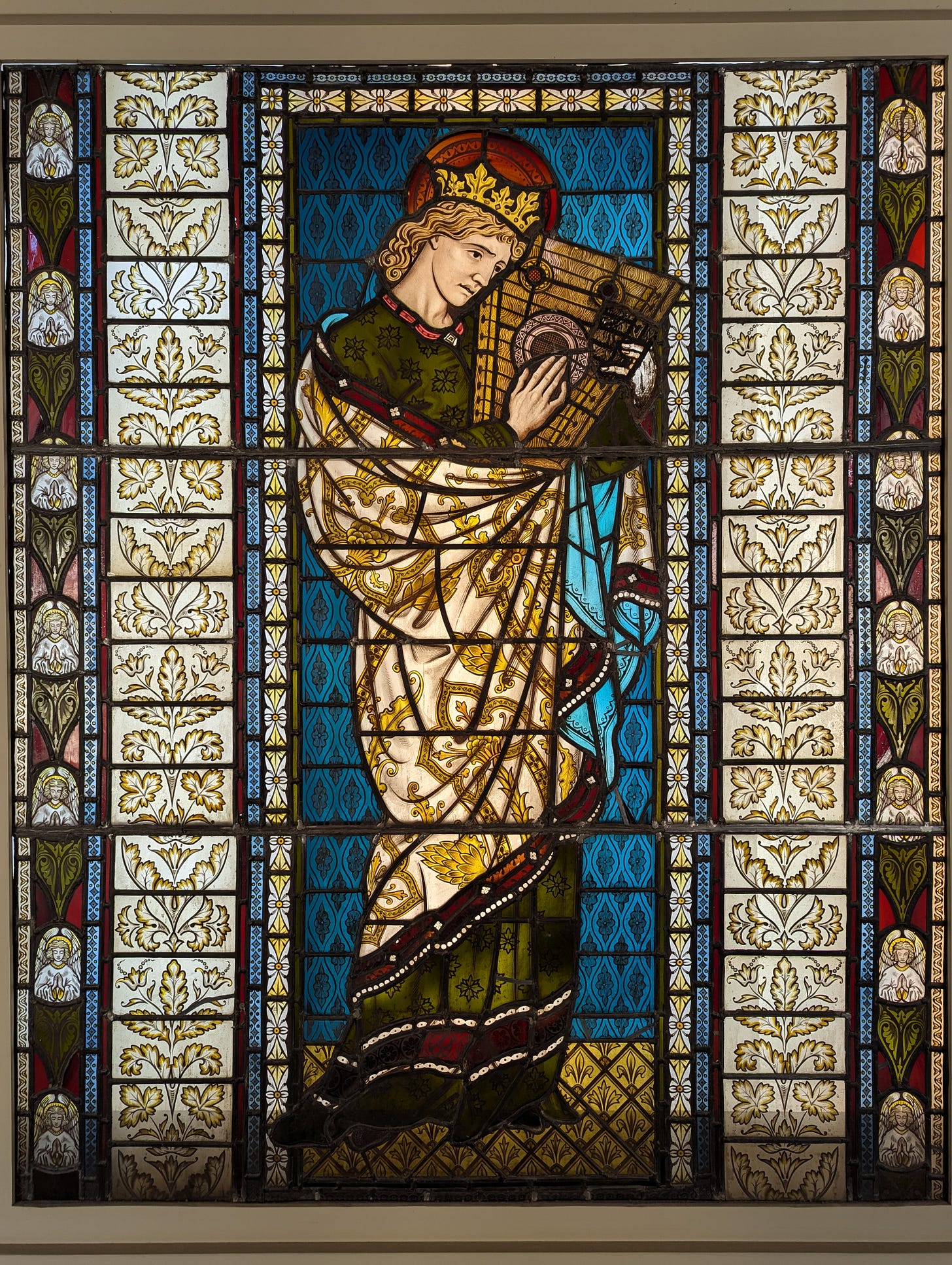

As the main part of the cathedral was not open for tours while the children’s performance was still ongoing, we visited the stained glass museum in the triforium of the cathedral. The children were in fine voice, although some of their repertoire, especially sea shanties such as ‘A Drop of Nelson’s Blood’ was incongruous in the context! The museum is the only one of its kind in the UK, with a marvellous collection. As elsewhere in the cathedral, it especially showcased the splendour of Victorian craftsmanship.

We decided that, while we were waiting for the cathedral to reopen for tours, we would have a full English breakfast at a pub.

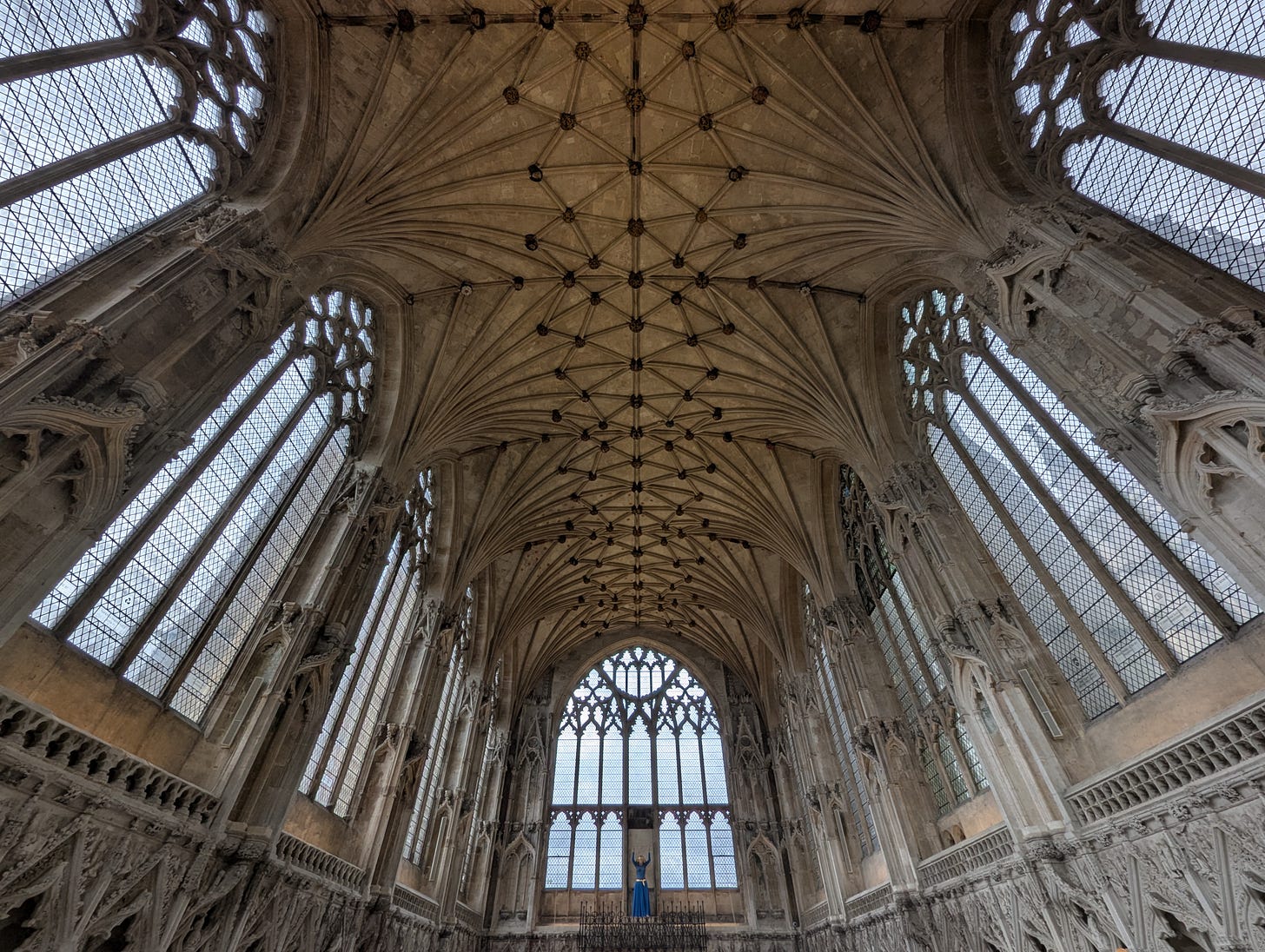

On our return, I booked a ticket for an Octagon tour, while Esther decided to have a guided tour of the ground floor of the cathedral. Before our tours began, we visited the Lady Chapel, where they had a display of clerical vestments.

The Lady Chapel is a gloriously ornate building, light and spacious, larger than any other lady chapel in the country. Once decorated with numerous figures painted in bright colours, almost all were defaced during the Reformation.

The construction of the Lady Chapel likely contributed to the collapse of the central crossing tower of the cathedral, which fell during February 1322. However, this occasioned the construction of what is the most distinctive and renowned feature of Ely Cathedral: the Octagon.

The Octagon was one of the wonders of the medieval world, a masterpiece of engineering and a design of awe-inspiring beauty. In the place of the old tower, they constructed a vast octagonal structure, with a lantern of stained glass windows above it to let the light in. It is a marvel of light and creative brilliance.

The tour group ascended a spiral staircase near the Lady Chapel, stopping at a lower level to drop off bags and other belongings. From there we could see the ceiling of the north transept more closely. We then went up another level, walking out onto the roof of the north transept and across to the extremely narrow staircase of the octagon tower. The staircase led to the interior of the wooden lantern structure, where vast wooden beams supporting the structure surrounded a central walkway. This walkway went around the exterior of the octagon that one sees from the inside of the cathedral.

Looking up from the ground of the cathedral, one sees the eight sides of the octagon, each with four angel panels, surmounted by a stained glass window. The Octagon tour takes you to the other sides of the angel panels, two of which our tour guide opened. From their vertiginous height one could see down into the cathedral.

We then went up a further level, to the roof of the octagon, where we saw the other side of the lantern. The West Tower of the cathedral is much taller than the Octagon Tower, but the latter still afforded spectacular views over the surrounding countryside.

After walking around the lantern on the roof of the Octagon Tower, we returned to the ground floor of the cathedral, where I took some more time to admire the timber boarded ceiling of the nave. The ceiling was first installed by the Victorians and painted without a fee by a gentleman artist, Henry Styleman Le Strange. After his death, his friend Thomas Gambier Parry (who also painted the angels in the octagon, as an illustration of Psalm 150) completed it.

After looking through the cathedral shop, Esther and I went to a café for tea and cake. From there we meandered down to the riverside and back to the train station.

That evening, James Bejon and I went out for a drink and caught up in person for the first time in a few years. We see each other online every fortnight for our Theopolis podcast recordings, but it was wonderful to see him again in the flesh. He had just successfully defended his PhD thesis, so there was occasion for celebration too.

The next morning, I went into the town, where I met up with the friend I had (almost literally) bumped into on his bicycle on Tuesday for a coffee and a long conversation about the book of Hebrews and other things. Susannah arrived from Stoke just as we were parting.

Susannah always comes alive in a place like Cambridge. We walked around, visited the Cambridge University Press bookstore, and a few second-hand and antiquarian bookstores, one of which, G. David, dates to the end of the nineteenth century and has an incredible selection of volumes. Susannah and I stayed there until after its closing time. We then met up with our friend Devon for a pub meal. We last saw Devon with several other Tyndale folk at the coronation in May 2023 and it was wonderful to reconnect with her.

I left early for the office hour for my Davenant Psalms course, while Susannah and Devon went to evensong.

We started the next day with a full English breakfast in the town and some more wandering and shopping for books, before returning to Tyndale for coffee, where we caught up with Peter Williams, James Bejon, and a couple of others. After chatting with them for a while at Tyndale, we went on to Selwyn College for lunch.

After that, we headed back into town, where we worked for a little while before having another coffee with our friend Dru Johnson, who was over from the US. We last spent time with Dru at a memorable meal in NYC with Ari Lamm, when Dru was still teaching at King’s College, and we had not anticipated seeing him on this side of the Atlantic.

Later that evening, we joined another friend who was up from Portsmouth for a meal. Again, I left early to get back to teach my Psalms course. However, I had not realized that the clocks had changed in the US over the weekend (ours have yet to change), so started the class an hour late—the first time I have made that mistake!

We were leaving the next (Saturday) morning. However, before we left we had the privilege of hearing Esther Meek speaking at Tyndale House, where several other friends and acquaintances whom we had not anticipated seeing were also in attendance. Esther is a Christian epistemologist. Although I had attended her Theopolis intensive course, Susannah had not heard her speak in person before, and was deeply impressed. Esther is a brilliant and grandmotherly philosopher and hearing her is always a delight. We managed to catch up with some of our existing friends and acquaintances beforehand and during the coffee break, and also met a couple of new people. Unfortunately, we were unable to stay for Dru’s talk, as we had to head back to Stoke.

Last week we had a few days of a regular schedule, but on Thursday morning I had to leave for Belfast, as I was one of the two examiners of a PhD at Union Theological College the next morning. I flew from Manchester Airport, so thankfully avoided all the chaos that struck Heathrow the following day.

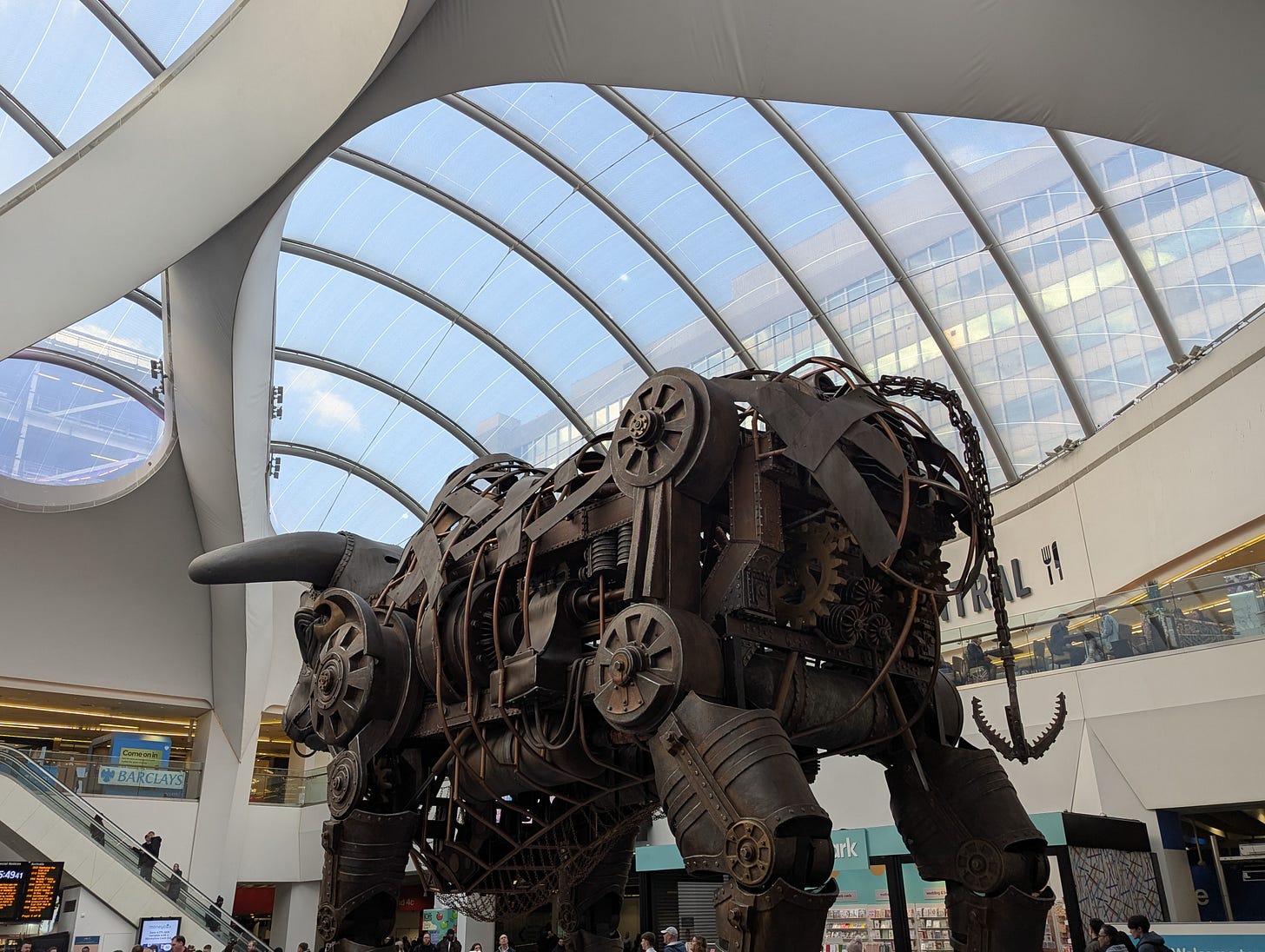

It was my first time visiting Belfast in over twenty-five years and I was extremely impressed by the city. We occasionally visited Northern Ireland when I was a child growing up in the Republic of Ireland, but that was during the Troubles and my childhood memories of visiting Belfast always involved some vague sense of the threat of violence (the scars of which were visible in various places). As a city, Belfast seems to be doing very well for itself.

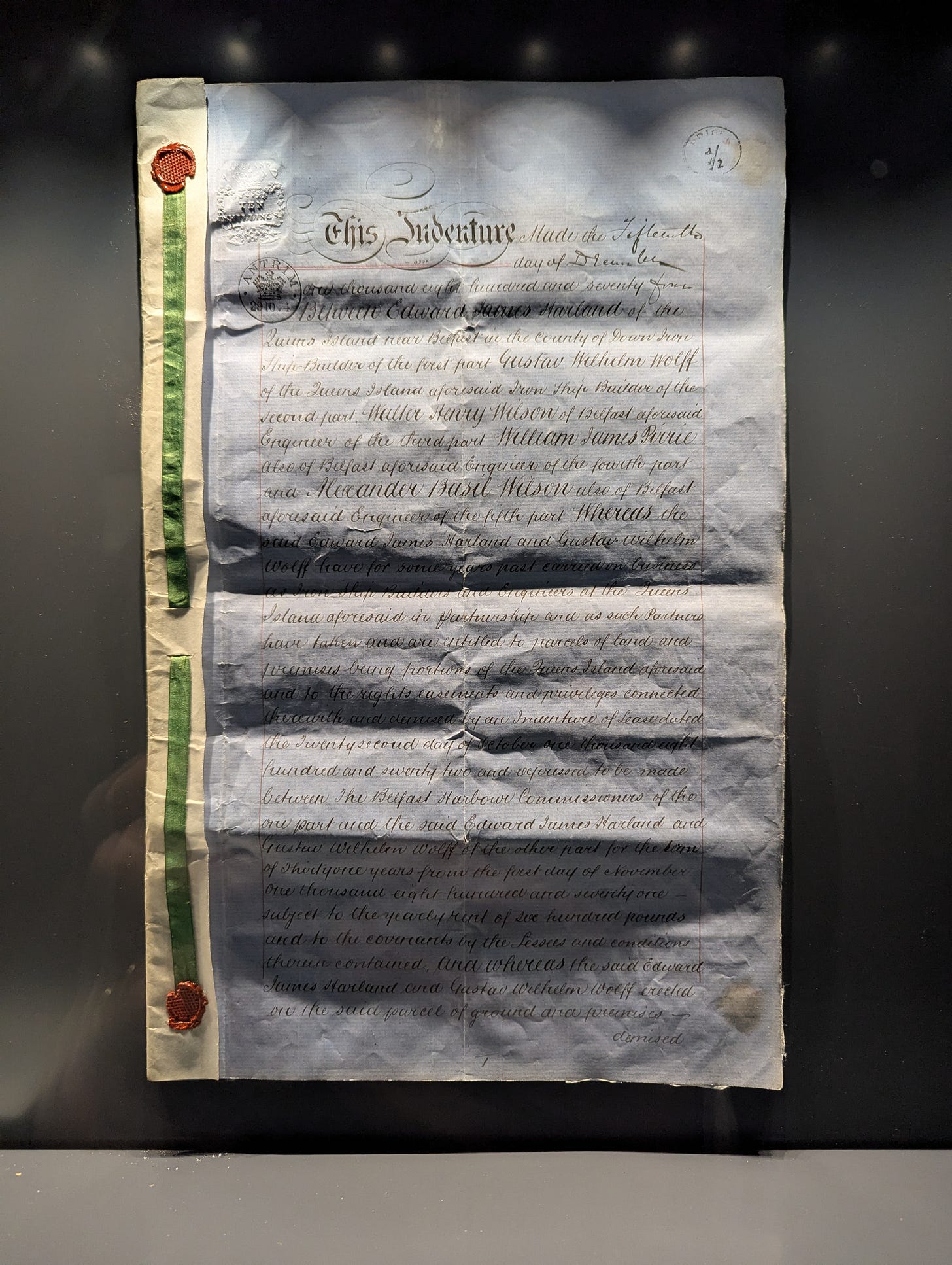

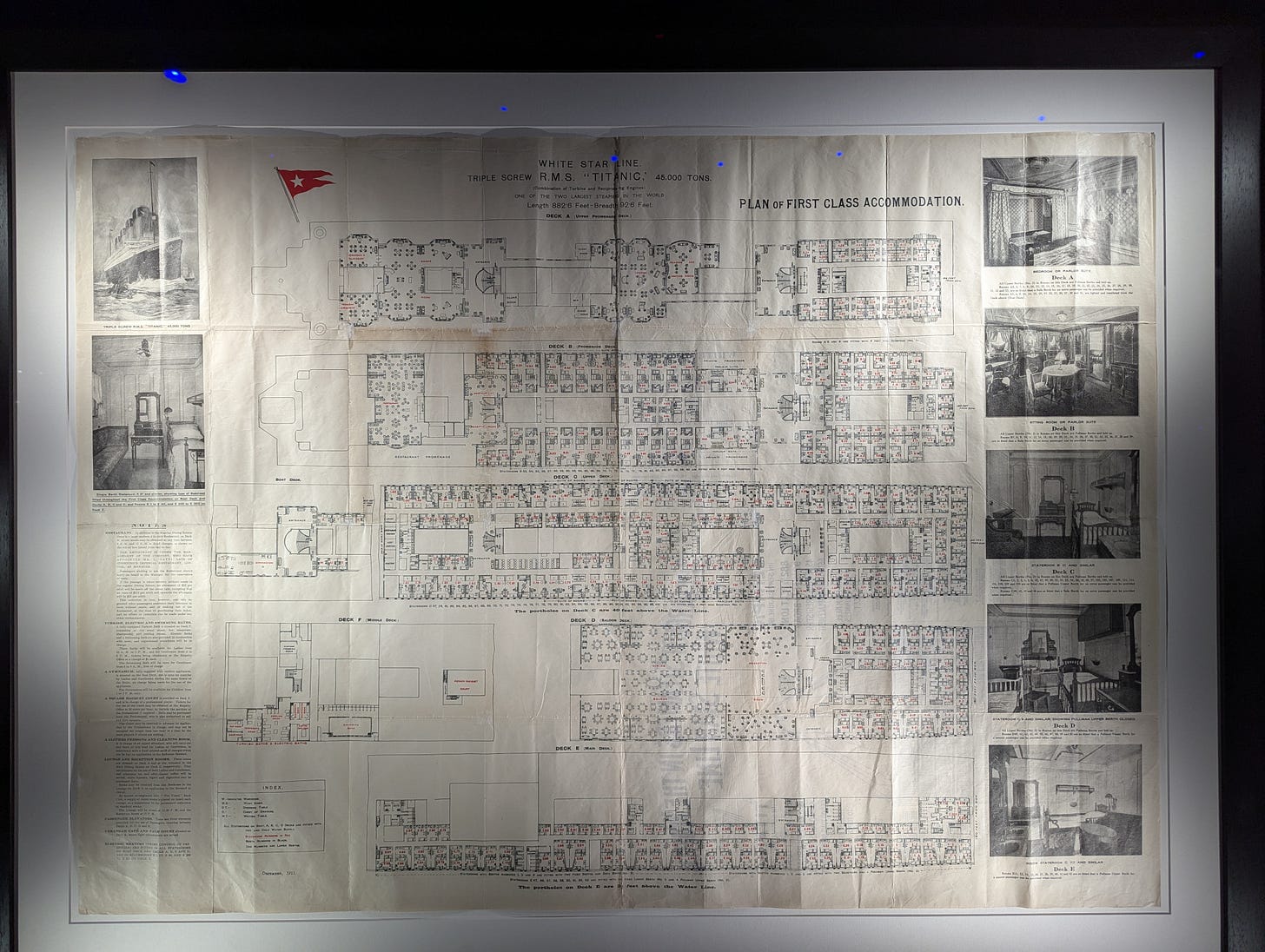

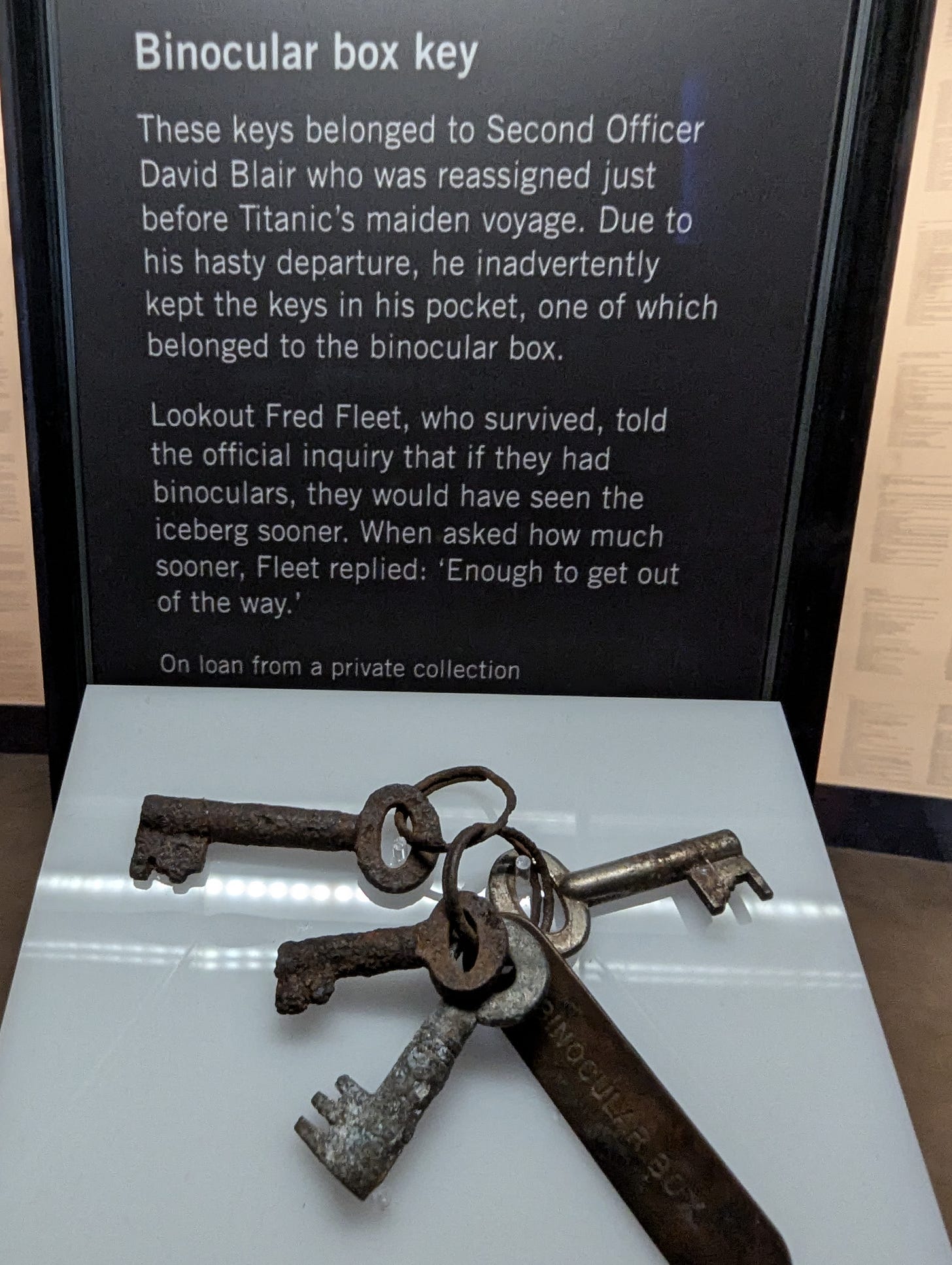

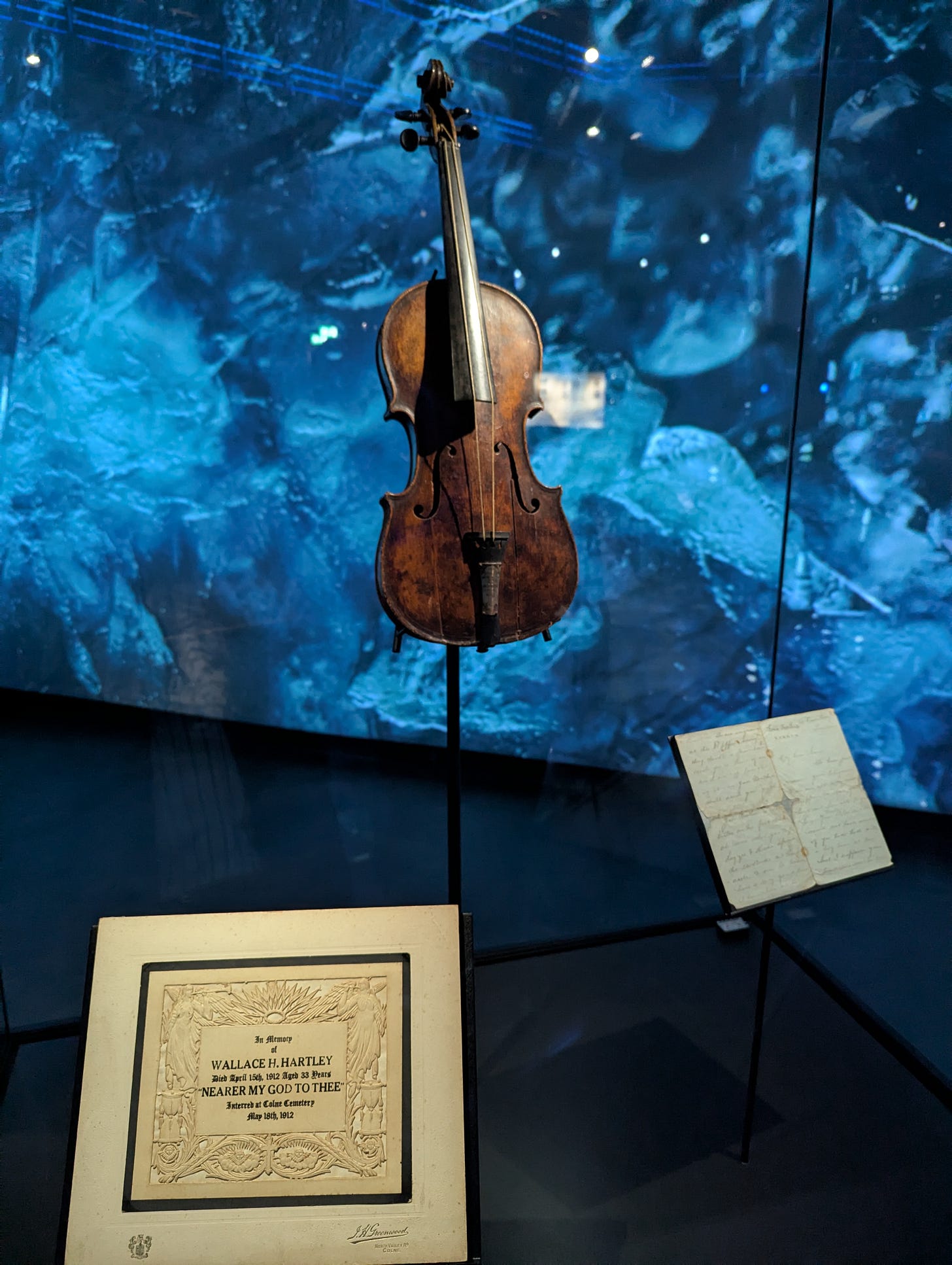

I went straight from the airport to the Titanic Belfast museum, next to the Harland & Wolff shipbuilding yard where the famous vessel was constructed. The RMS Titanic represents an important bond between Belfast and my two hometowns: Belfast built her, a Stoke man, Edward John Smith, captained her, and she sank en route to Manhattan. Before going into the museum, I walked around the shipbuilding yard and also around the dry dock of the SS Nomadic.

Titanic Belfast is easily one of the finest museums of its kind I have visited. It tells the incredible story of Belfast’s shipbuilding history. Belfast used to be the largest shipyard in the world and, in its heyday, employed over 35,000 people. Harland & Wolff’s iconic gantry cranes, Samson and Goliath still dominate the horizon.

The museum recounts the history of Harland & Wolff, introduces visitors to the processes of shipbuilding, and, in a series of engaging and brilliant exhibits, leads visitors through the story of the construction of the Titanic, the character of life on board, its departure from Belfast, its fateful maiden voyage, the disaster of its sinking, the discovery of its wreck, and its afterlife in the public imagination. You ascend a mock gantry, ride a mini-car through the bowels of a shipbuilding factory, have a 360-degree video tour through the levels of the Titanic, see replica rooms from the vessel, and much else.

One of the most powerful parts of the museum for me came after the museum’s display of Robert Ballard’s discovery of the wreck. The route opened out into a large two-storey chamber, around which a staircase descended to the level below. On the walls were moving images of the building of the ship and of persons who went down with her, with background music. Hung in the centre was a large model of the Titanic slowly rotating, beneath which a video of the wreck could be seen through the glass floor. The lower level of the room was surrounded by evocative exhibits from the ship.

From the museum, I made my way into the city along the Maritime Mile. Belfast has an attractive waterfront, as the River Lagan flows through the city and out into the Irish Sea. Along the route there are several pieces of stained glass art commemorating the TV show Game of Thrones, much of which was filmed in the city and the surrounding region.

I crossed the Lagan Weir Bridge next to the Custom House and the Big Fish and then made my way towards Belfast City Hall. Besides its shipbuilding, Belfast used to be the world’s leading city for linen manufacture and the grandeur of the architecture of the city centre and the various civic buildings testifies to its historic importance. Belfast also appears to be thriving at the moment.

I stayed in an Airbnb overnight. I had toyed with the idea of getting up early and climbing up to McArt’s Fort to look out over the city. However, it was overcast and my time was limited, so I decided to leave that for another trip—I would love to return with Susannah before long. I read for a while instead and then slowly wandered through the park and the Botanic Gardens and met up with my fellow examiner for a coffee.

After being talked through the process of the examination by the principal of the college, we examined the PhD thesis for two hours. The candidate was very competent and clearly knew his research and the field well and answered thoughtfully and confidently, which made our task largely a pleasant one.

Following the examination, we went to a restaurant for a meal and were given a brief tour of the college. The college, the theological college for the Presbyterian Church in Ireland, is in an imposing Renaissance Revival building. I was amazed to discover that its library was the Chamber of the House of Commons for the Northern Ireland Parliament for fourteen sessions between 1921 and 1932.

Before returning to the airport, I looked through the SS Nomadic, which had closed before I had been able to visit the day before. The Nomadic was a former tender of the Titanic and is the last remaining White Star Line vessel. It is still undergoing restoration, but gives a small window into the class and luxury of the vessels that she was designed to serve.

From leaving Belfast, I arrived home in two and a half hours.

The last few days have been quiet ones. We discovered a new antiques store in walking distance of our home and joined my parents for a meal after church on Sunday, but have mostly been working.

Yesterday afternoon we visited Trentham Gardens, as the weather was glorious and we had not visited in a while. After briefly looking around the shopping village, we walked around the lake. The gardeners at Trentham do an incredible job and, virtually every time we visit, we notice something new that they have added, along with signs of the shifting seasons. This time we saw several new wicker sculptures.

They are reintroducing beavers in the area and, even though we did not see any, we were excited to see several signs of their presence. There were also a pair of pheasants.

Hebrews and Christian Psalm-Singing

In my experience, some of the more interesting lines of investigation are opened when two or more books that you were reading, or subjects you were studying, start unexpected conversations between themselves. Over the past few weeks, I have been teaching my Davenant Hall course on the Psalms; at the same time, our Theopolis podcast series on the book of Hebrews has been getting underway. While it is not my first time noticing the prominence of the Psalter in the book of Hebrews, it had not formerly hit me just how important psalms are within it.

No book is more quoted in Hebrews than the Psalter: there are quotations and allusions to psalms on virtually ever page. And many of the quotations are not merely passing references, but are closely considered and repeatedly cited as the author of Hebrews develops his central arguments. Much of Hebrews is exposition of the Psalms, not mere scattered allusion or citation.

Key passages from the psalms for Hebrews include Psalm 2:7—

I will tell of the decree: The Lord said to me, “You are my Son; today I have begotten you.”

This text is cited in both Hebrews 1:5 and 5:5, which relate it to Christ’s exaltation and appointment to his royal priestly office.

Psalm 102:25-27, cited in Hebrews 1:10-12, introduces an important theme for the book—the expected eschatological reordering of all things, a theme that becomes especially prominent in chapter 12. We might also hear an anticipation of Hebrews 13:8—‘Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today and forever.’

Of old you laid the foundation of the earth, and the heavens are the work of your hands. They will perish, but you will remain; they will all wear out like a garment. You will change them like a robe, and they will pass away, but you are the same, and your years have no end.

Two texts from Psalm 110, verses 1 and 4, are given attention in the argument of Hebrews:

The Lord says to my Lord: “Sit at my right hand, until I make your enemies your footstool.”

The Lord has sworn and will not change his mind, “You are a priest forever after the order of Melchizedek.”

The second text, which speaks of the enduring priesthood of Melchizedek, provides the scriptural backdrop for the considerations of 5:6-10 and 6:13—7:28.

Psalm 8:4-6 comes to the foreground in 2:5-9, where Hebrews relates it to Christ’s incarnation and exaltation:

what is man that you are mindful of him, and the son of man that you care for him? Yet you have made him a little lower than the heavenly beings and crowned him with glory and honor. You have given him dominion over the works of your hands; you have put all things under his feet…

Hebrews riffs upon Psalm 95:7-11 in 3:7 to 4:11.

Today, if you hear his voice, do not harden your hearts, as at Meribah, as on the day at Massah in the wilderness, when your fathers put me to the test and put me to the proof, though they had seen my work. For forty years I loathed that generation and said, “They are a people who go astray in their heart, and they have not known my ways.” Therefore I swore in my wrath, “They shall not enter my rest.”

Psalm 40:6-7 is deployed in a surprising way in 10:5-14, where it is related to Christ’s perfect self-offering.

In sacrifice and offering you have not delighted, but you have given me an open ear. Burnt offering and sin offering you have not required. Then I said, “Behold, I have come; in the scroll of the book it is written of me...”

Alongside these more extensive uses of the Psalms are several other citations and allusions. For instance, Psalm 22:22 is cited in 2:11-12, Psalm 45:6-7 in 1:8-9, and Psalm 118:6 in 13:6. Even these, however, are not merely passing references, but provide indications of the remarkable way that the author of Hebrews reads the Psalms.

There is no better way to learn how to read the Scriptures than by following the Scriptures’ own example. We can learn typological and Christological reading of the Old Testament scriptures from passages such as 1 Corinthians 10, extending such a pattern of reading to texts beyond those referenced by Paul in that passage. The books of John and Revelation offer an allegorical reading of the Song of Songs. And the book of Hebrews teaches us how to read the Psalms in the light of Christ.

A detailed treatment of the reading of the Psalms in the book of Hebrews would take longer than I have here. [Susannah: Because obviously we are terribly concerned about keeping these substacks to a sensible length.] Fortunately, after having taught on the subject in a recent class of my Davenant course on the Psalms, a student alerted me to Daniel Stevens’ book, Songs of the Son: Reading the Psalms with the Author of Hebrews, which has just been released by Crossway. I have since purchased a copy, although I have yet to read through it (skimming a few sections, it looks very helpful—I suspect it would further flesh out much that I discuss below). Rather than handling each text individually, I want to make a few general points about how Hebrews teaches us to read the Psalms.

1. The Psalms are fulfilled in Christ

Hebrews presents Christ as the one in whom the psalms are fulfilled. The Psalter opens with a pair of psalms that establish core themes of the book. Several New Testament authors reference or allude to Psalm 2, relating it to Christ’s exaltation. In Acts 4:24-28, the apostles present the gathering of the rulers and the crowds against Jesus in the crucifixion as the fulfilment of Psalm 2:1-2—

And when they heard it, they lifted their voices together to God and said, “Sovereign Lord, who made the heaven and the earth and the sea and everything in them, who through the mouth of our father David, your servant, said by the Holy Spirit, “‘Why did the Gentiles rage, and the peoples plot in vain? The kings of the earth set themselves, and the rulers were gathered together, against the Lord and against his Anointed’—for truly in this city there were gathered together against your holy servant Jesus, whom you anointed, both Herod and Pontius Pilate, along with the Gentiles and the peoples of Israel, to do whatever your hand and your plan had predestined to take place.

Hebrews 1:5 and 5:5 both relate Psalm 2:7 to the exaltation of Christ, much as Acts 13:33 sees its fulfilment in the resurrection. There are various allusions to Psalm 2 in the book of Revelation, of course, most notably in passages such as 2:26-27, 12:5, and 19:15, which present Christ as the divinely appointed Messiah in Psalm 2 who rules with the rod of iron.

That the author of Hebrews quotes several verses of various psalms suggests that he is not merely cherry-picking decontextualized scriptures that can be applied to Jesus, but that a more consistent reading of the psalms in the light of Christ undergirds his use of specific verses and passages. For instance, both verses 1 and 4 of Psalm 110 are cited in different parts of Hebrews (1:13; 5:6). Likewise, the extensive use of psalms like Psalm 110 in several parts of the New Testament suggest that such readings were not idiosyncratic, but common in the early Church.

The Christological reading of the Psalms in Hebrews also includes a passage like Psalm 8:4-6, which is generally read as referring to humanity more broadly (Hebrews 2:5-8). Hebrews, however, treats the passage as relating to Christ most fully. I think it is helpful here to recall that Psalm 8 is a psalm of David and that, in being raised to the throne, David is a representative man enjoying something of the dominion to which man was appointed in Genesis 1:26-28. This makes the move to Jesus as the representative Man in whom humanity’s destiny is realized a very natural one.

2. Christ is addressed in the Psalms

In Matthew 22:41-45, Jesus argued with the Pharisees from Psalm 110:1, arguing that David’s son could not have been the figure addressed in the opening verse of the psalm, as David called him ‘Lord’. Hebrews approaches the Psalms in a similar manner, attentive to the different implied speakers of its words and those being addressed. Jesus is the one of whom Psalm 110:1 is spoken—‘Sit at my right hand, until I make your enemies your footstool’ (Hebrews 1:13).

Hebrews makes similar points about other texts from the Psalms, especially in the opening chapter: Jesus is addressed in Psalm 2:7 (verse 5), Psalm 45:6-7 (verses 8-9), and Psalm 102:25-27 (verses 10-12). The author of Hebrews traces a line of biblical reflection here. He moves from the exaltation of the Son (Psalm 2:7), to the declaration of his Sonship in the words of the Davidic covenant, but as the archetype of which David’s throne was the ectype (2 Samuel 7:14), to the worship due to him by the angels (Deuteronomy 32:43), to the enduring and superior character of his throne from Psalm 45, with its themes of royal marriage and enthronement. Psalm 102:25-27 follows this line of biblical reflection, perhaps connected to the preceding reference from Psalm 45 by the unreferenced association of Psalm 102:12 with 45:6—‘But you, O Lord, are enthroned forever…’ Perhaps he also sees—as James Bejon noted in one of the recent episodes of our Hebrews study on the Theopolis podcast—a significant shift from ‘Lord’ to ‘God’ in Psalm 102:24, suggesting a change in speaker or addressee.

As the themes introduced by Psalm 102’s treatment of the transformation of the heavens and earth are taken up again in chapter 12, the use of the quotation from Psalm 102 in Hebrews 1 frames the book’s eschatological themes by the supremacy and unchanging character of Christ: ‘Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today and forever’ (13:8).

3. Christ is the chief Speaker of the Psalter

In Hebrews 10:5-7, the author of Hebrews places the words of Psalm 40:6-7 upon the lips of Christ as he came into the world. The psalmist’s words are read as applying chiefly to Christ’s incarnation.

In singing the Psalms, we borrow the words of psalmists, chiefly David, to speak of our own experiences. Especially when singing the psalms of David, the identity of the psalmist might itself be important for our singing of them. As the anointed king, the destiny of the people is to be realized in David and his seed, David’s own personal struggles are paradigmatic for others, and, importantly, David’s words anticipate and strain towards their full realization in his greater Son.

The New Testament presents the words of the Psalms as principally being the words of Christ. They are inspired by the Spirit of Christ. As David speaks of his experience, by the Spirit he prophetically anticipates Christ. David’s representative character is eclipsed by the far more representative character of Christ. And Jesus is the paradigmatic righteous suffering king that David foreshadows.

The Psalter begins with a portrayal of the righteous man, who meditates upon God’s Law day and night, and with the faithful king that the Lord has established over the nations on Zion’s hill. Both these figures are anticipated in David, the ‘sweet psalmist of Israel’, yet only fully realized in Christ.

Psalm 40 is a great example of the hermeneutic that this implies in action. The figure of the faithful suffering king is ultimately seen in Christ’s taking of flesh and his self-offering.

4. Christ is the ground and the paradigm of the new covenant

The Old Testament scriptures anticipated a time when the resistance of the people’s hearts to the Law of God would be overcome, as the Lord would place his Law within their hearts (Deuteronomy 30:6; Jeremiah 31:33; Ezekiel 11:19-20; 36:26-27). When reading the psalms, we have an anticipation of this new covenant reality in the figure of the psalmist, who meditates upon and delights in the Law of the Lord and treasures it in his heart.

…his delight is in the law of the Lord, and on his law he meditates day and night… (Psalm 1:2)

The mouth of the righteous utters wisdom, and his tongue speaks justice. The law of his God is in his heart; his steps do not slip. (Psalm 37:30-31)

With my whole heart I seek you; let me not wander from your commandments! I have stored up your word in my heart, that I might not sin against you. (Psalm 119:10-11)

The law of the Lord is perfect, reviving the soul; the testimony of the Lord is sure, making wise the simple; the precepts of the Lord are right, rejoicing the heart; the commandment of the Lord is pure, enlightening the eyes; the fear of the Lord is clean, enduring forever; the rules of the Lord are true, and righteous altogether. More to be desired are they than gold, even much fine gold; sweeter also than honey and drippings of the honeycomb. (Psalm 19:7-10)

Notably, the author of Hebrews concludes his quotation of Psalm 40 just before verse 8, which reads:

I delight to do your will, O my God; your law is within my heart.

Like cutting off a familiar piece of music before the end of a passage, though unsounded, the unplayed notes still hang in the air. That Hebrews immediately moves to discussing Jeremiah 31:33’s promise of the new covenant and the Law written on the heart is no accident. Christ is the Man of the new covenant, the Man with God’s Law in his heart, who renders true and perfect obedience to God. He is the One in whom the words of the Psalms discover their true Speaker. His coming is the new covenant arriving in person.

And, as the words of Psalm 40 are taken up by Christ to describe his incarnation and self-giving, not only is the ground of the new covenant revealed, but also the exemplary character of Christ as the founder and perfecter of faith (Hebrews 12:2), who is the pattern and the realization of the obedience to which we are called and in which we are formed. The Psalms, so read, will also come into their own as the natural expression of the new covenant. What does it look like to have the Law written on your heart? Singing psalms in which you express your delight in, meditation upon, and treasuring of God’s Law.

…be filled with the Spirit, addressing one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody to the Lord with your heart… (Ephesians 5:18-19)

Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly, teaching and admonishing one another in all wisdom, singing psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, with thankfulness in your hearts to God. (Colossians 3:16)

5. The words of the psalter speak directly into our situation

In one of the most challenging passages of the New Testament, the author of Hebrews charges and exhorts the hearers of his epistle using the words of Psalm 95:7-11. For most of chapters 3 and 4 of his epistle he expounds and addresses the psalm to their situation. The psalm, which looks back to the rebellions of Israel in the wilderness, and chiefly to their refusal to enter the Promised Land, is directly applied to Christians who might be tempted to turn back when facing growing persecution.

The ‘rest’ of the psalm, which refers to the Promised Land from which the unfaithful Israelites were excluded in Numbers 14:20-38, is applied to the ‘rest’ of the new covenant, and also related to the ‘rest’ of God established at the first Sabbath of creation. The Christians hearing the epistle being read need to press forward with a sense of urgency, not wanting to miss out on what God has in store for them: entrance into the true Promised Land (cf. Hebrews 11:13-16) and the completion of human labours in Christ, who realizes the original rest and dominion held out to Adam.

Like 1 Corinthians 10:11—Now these things happened to them as an example, but they were written down for our instruction, on whom the end of the ages has come—the author of Hebrews implies a typological reading of Israel’s experience, which foreshadows that of the Church and, consequently, can speak directly into the Church’s experience.

6. Christ leads the worship of his people

One of the most striking uses of a psalm in Hebrews is seen in 2:12, which quotes the words of Psalm 22:22—I will tell of your name to my brothers; in the midst of the congregation I will praise you. Hebrews uses this verse to prove Christ’s kinship with those whom he redeems—he is not ashamed to call them brothers (2:11).

Once again, the choice of psalm here is noteworthy. While only one verse of it is quoted, Psalm 22 was a prominent Messianic psalm for the early Church and is clearly referenced within the crucifixion narratives of the gospels, with its words on the mouths of Jesus, the crowd, and the evangelists. Most famously, its opening words are on Jesus’ lips on the cross: ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’ (Matthew 27:46; Mark 15:34). The taunt of the mockers in Psalm 22:7-8 is on the mouth of the passers-by in Matthew 27:39-43. The division of garments mentioned in Psalm 22:18 is recorded as a narrative event in Matthew 27:35. Any attentive reader of Matthew’s crucifixion account in particular should recognize it as Christological commentary on Psalm 22.

When the New Testament cites the Old, we should typically not hear its citations as isolated references. So often New Testament citations of the Old are calculated to evoke wider passages and their associations. When reading Hebrews 2:12, where the psalmist of Psalm 22 declares his praise for his deliverance in the midst of his brethren, we should probably hear the entire narrative of the psalm in the background (we might also hear an allusion to Psalm 22:24 in Hebrews 5:7). The deployment of this reference follows the description of Christ as the man who ‘tasted death for everyone’ (2:9). Christ’s singing in the midst of the congregation of his brethren is a triumphant manifestation of the fruit of his redemption. As Christ leads his people in song, his own vindication is being declared and the spoils of his victory displayed.

I have considered the attention that the author of Hebrews gives to the speakers in the Psalms, and the fact that the voice of Christ is the chief of its voices. Colossians 3:16 quoted above might also suggest a close connection between Christ’s speech and the words of the psalms. When we sing the psalms, we take the words of Christ within and make them our own. Yet those words do not cease to be Christ’s and our singing of the psalms can be a form of his dwelling in—and singing through—us.

In a wonderful short book, From Silence to Song: The Davidic Liturgical Revolution, Peter Leithart observes the way that the worship of Israel was described in places like 1 Chronicles 25:2 and 2 Chronicles 7:6 as David’s worship, ministered by the Levites.

On the one hand, the musicians performed “under the hand” of David; on the other hand, David himself praised Yahweh “by their hand.” Levitical praise is the King’s Song before his “Father,” even if it is performed by Levites. And it was David’s song even though David was not present.

Leithart proceeds to connect this with the use of Psalm 22:22 in Hebrews 2, suggesting that it presents Christ as the One who leads the worship of his people:

Gathered for worship, united in song, the body of Christ, along with the Head, is Christ offering praise to His Father. The Greater David gives praise by our hand.

7. We take the words of the psalms as our own

The final citation of a psalm in Hebrews is found in 13:6, which quotes Psalm 118:6—

The Lord is on my side; I will not fear. What can man do to me?

Psalm 118 tells a story of the psalmist’s distress and the Lord’s deliverance, leading to a glorious expression of praise. The Lord rescues the psalmist from death and from his adversaries and the psalmist praises him for his goodness. It is another psalm that is read as Messianic in the New Testament, especially the words of verse 22—The stone that the builders rejected has become the cornerstone—which is related to Christ in Matthew 21:42, Mark 12:10, Luke 20:17, Acts 4:11, and 1 Peter 2:6-7. The words of verse 26 of the psalm—Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!—are also famously quoted in the gospels’ accounts of the Triumphal Entry (Matthew 21:9; Mark 11:9; John 12:13) and in Jesus’ words of judgment upon Jerusalem (Matthew 23:39; Luke 13:35).

In the use of Psalm 118:6, Hebrews plots the experience of the embattled hearers of his epistle onto the story of the psalm. The confidence of the psalmist expressed in the quoted verse draws upon all the messianic themes within the original psalm and their fulfillment in Christ, and upon the pattern of redemption the psalm describes. In Hebrews 13:6 we are invited to take the words of the psalm as our own, declaring them with assurance and confidence.

The psalms, understood in such a way, are the form that God has given us in which we can express our joyful response to his redemption and victory. And strengthened by the confidence expressed in the psalm, we will be assisted to live in light of the reality it proclaims. In Psalms as Torah: Reading Biblical Song Ethically, Gordon Wenham speaks of the power of ‘prayed ethics’. To pray—or, better, to sing—psalms is self-involving and performative. He writes:

In praying the psalms, one is actively committing oneself to following the God-approved life. This is different from just listening to laws or edifying stories. It is an action akin to reciting the creed or singing a hymn. It involves strong commitment, and this is why I think that the psalms have been so influential in molding Jewish and Christian ethics in the past, and why as scholars we should again study them for their ethical content.

When Hebrews tells its hearers to declare the words of Psalm 118:6 with confidence, it is charging and equipping them to commit themselves to a certain posture. In this, among other ways, taking the words of the psalms as our own assists us in living faithfully as Christians and conforms us to Christ, whose words they are.

8. The Psalms are our sacrifice of praise

Sacrifice is, of course, a central theme of the book of Hebrews. In Christ, the sacrifices of the old covenant, which could never take away sins, are fulfilled in a once-for-all sacrifice that forgives sins, perfects worshippers, and opens a new and living way into the presence of God. Consequently, there is no need for a continued offering for sin.

However, although we no longer offer bulls, goats, and other animal sacrifices, sacrificial practices remain central in the life of the Church. In contrast to much Christian theology, in Leviticus, sacrifice did not focus upon the act of killing of sacrificial animals. Rather, the central acts of sacrifice were actions with the blood of the sacrificial animal, the ascending of the sacrifice in fire, and communion meals. Such patterns remain in the worship of the Church, even though they are now humanized. Christ’s blood is ritually applied to us in baptism and in continued confession and absolution of sins. When Hebrews says that ‘we have an altar’ from which we have an exclusive right to eat (13:10), we should hear a reference to the celebration of the Supper, where Christ offers us his body and blood.

In describing the ‘sacrificial’ worship of the new covenant at the conclusion of the book, the author of Hebrews broadens the application of principles of sacrifice. We participate in the sacrifice of Christ (as we eat from the altar outside the camp) and we also do good to and share what we have with others, ‘for such sacrifices are pleasing to God’ (13:16). Through Christ we also ‘continually offer up a sacrifice of praise to God, that is, the fruit of lips that acknowledge his name’ (13:15).

As Leithart observes in From Silence to Song, already in the old covenant, animal sacrifice was being progressively more humanized through the addition of music and song, especially by David. The place of song, and particularly psalms, in Christian worship should be understood accordingly. Song can memorialize the deeds of the Lord, like sacrifices could act as memorials. Song can represent the offering of the worshipper in true and joyful commitment of heart, the sort of offering described in Psalm 40:6-8. Most importantly, considering what we have discussed to this point, singing psalms can be a form of union with the risen and exalted Jesus Christ. The ‘fruit of lips’ that acknowledge God’s name spring forth from and articulate transformed hearts that have his Law written within them. And this was always the sacrifice that God most desired.

God desired the wholehearted offering of the true embodied worshipper, an offering that is finally given in Christ (Hebrews 10:5-14). In Christ’s self-offering, our offering of ourselves in him is made possible. As we sing the psalms, nothing less than this should be our animating vision.

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ The Theopolis podcast series on Hebrews continues, with the following episodes: The One Who has the Power of Death (Hebrews 2:14—3:2), Do Not Harden Your Hearts (Hebrews 3:3-19), and They Shall Not Enter My Rest (Hebrews 3:7-14).

❧ I have an article in the latest issue of Plough: ‘The Divine Rhythm of Work and Sabbath’.

Man’s work was supposed to flow out of and back into fellowship with God: it was ordered out from and into the sanctuary. However, after humanity’s rebellion in the Fall, human labor went awry, adopting a different character. Alienated from God, human labor lost its primary orientation to communion, becoming acquisitive, driven by a desire for material possessions, power, and status. Capacities that were created for beneficent rule were twisted to the ends of domination over others, and labor became entangled with systems of bondage. Mutual recognition, companionship, and belonging through fellow labor curdled into rivalry and division. Work once blessed with fruitfulness was reduced to frustration and futility. Labor degraded into unrelenting toil. The earth no longer readily answered to the efforts of the man, and now, alienated from the Giver of Life, man’s labors were constantly slipping down into the pitiless maw of death. The labor of women in childbirth became hedged about with the risk of death, for mother and baby alike. The book of Ecclesiastes, which meditates upon the condition of man in a world under the power of death, describes how man’s greatest works are washed away and forgotten beneath the advancing tides of time.

❧ Christian Leithart invited me to write for his Good Work zine (which you should subscribe to here). I have an article in the new ‘Make Do and Mend’-themed issue.

How is our sense of divine presence in the world further transformed as our attention is increasingly saturated with virtual, immaterial, and infinitely digitally replicable “objects,” especially as many of those objects are generated by artificial systems, with minimal conscious human thought involved? In the growing capacity of mindless AI systems to generate texts and images—and even physical objects—we might feel a mockery of man’s place in the world, likely portending a further estrangement of humanity from what once was our lifeworld.

The “worlds” we inhabit are increasingly those of meaningless, impersonal, and insubstantial things. The objects that fill these “worlds” no longer feel grounded in a divinely created reality, not least because they no longer feel truly human. As one might walk upon the snow and ice upon a vast lake, unconscious of the depth of the water below, so the thin objects of our “worlds” can mask the forgotten yet fathomless depths of a Creation that draws its inmost being from its transcendent Maker. He is the One who holds all in being, who gives to each its unique existence, who orders each towards its appointed end, and represents the perfection that grounds all lesser goods.

❧ I wrote a response in the latest Theopolis Conversation.

In the contemporary world, we tend to measure value in money. However, the household is not commensurable, nor exchangeable, nor fungible; the labour proper to it is neither abstractable nor alienable. It is a network of life, which can extend and expand far beyond the four walls of a house. For instance, in the early Church, several women were patrons or hosts of churches, their own households spreading out to support communities and institutions beyond. The woman in Proverbs 31 forms her own household, yet her household is expansive, extending into the economic, civic, and political life of her society. The contrast with the work of the woman who earns a salary working for a corporation is not chiefly to be found in the location of their respective work, but in their ownership of their work: the Proverbs 31 woman is building up her own household and community, securing the commonweal of her family and neighbourhood.

❧ Empathy has been a live subject over the last few weeks, not least after Elon Musk claimed that ‘the fundamental weakness of Western civilization is empathy’ on the Joe Rogan Experience. Joe Rigney’s new book on the subject, The Sin of Empathy: Compassion and Its Counterfeits, came out and I was asked to review it for The Dispatch.

The historian of emotion Thomas Dixon observes the shift from a formerly sophisticated, highly structured, and typically theological account of our psychology, which distinguished between categories such as passions, appetites, desires, and affections and the large array of species of feeling within them (see, for example, the deadly sins and their corresponding virtues), to the dominance of the flattened-out, largely unordered, and secularized category of “emotions.” (See, for example, the few simple emotions portrayed in the Pixar film Inside Out.) As such a paradigm has gained popular traction, the subtle variations of an emotional lexicon that employed many terms such as rage, wrath, resentment, and fury has been subsumed to the basic emotion of “anger.” One might here wonder whether “empathy” might be getting the same treatment—that is, turning into a simplistic denominator for the motives of left-leaning politics, as people on the left have often attributed right-leaning politics to the emotion of “anger.”

❧ I have produced videos of some past Argosy reflections.

On ‘Empathy’

Characteristics of Dysfunctional Communities

A Lenten Reflection on the Cross

❧ I advertise my forthcoming Davenant course here:

Upcoming Events

❧ Much of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

❧ Alastair’s next Davenant Hall course, on Bible Reading Skills for Narrative Texts, is still open for registration (albeit with a late registration fee). The course begins on April 7th.

❧ We will be down in London for a Plough event on April 1st: ‘Why We Work: A Discussion with Alastair Roberts and Sebastian Milbank’. If you are in the area you should join us! Or you can watch the livestream.

Much love,

Alastair and Susannah

Well, if I'm going to say farewell to meat, I'd definitely like to go out in such a cosplay bang first. That was fun.

Wow, I feel like I just had an intensive educational experience! This was a gift, thank you for all the pictures of Venice! My favorites were the Pre-Raphaelite/Guinevere-lookalike maidens, and the shots of the city that look like Canaletto paintings. 😊