№ 42: An Obituary and Advent

Advent hermeneutics and the Temple as a symbol of absence and expectation

Susannah:

Joel Keehn: an Obituary

My uncle Joel Alexander Keehn died just under a month ago, in a hiking accident in the state park near his and my aunt’s house. He was 64, right in the middle of a very full life, just about to become a grandfather for the first time. It still feels surreal to write, but I wanted to write a little bit about him because that’s what I can do.

He was a journalist, an editor at Consumer Reports. The love and respect that his colleagues there have for him are wonderful: a whole other side of him than that we in the family normally saw. Nearly sixty of his colleagues showed up to the wake. He had specialized in the CR health and healthcare beat, and had taken part in or led many investigations that have filtered down into popular culture and practice: the dangers of some kinds of plastics in food, and so on. He recently led an investigation into a Fisher Price baby seat that had, because of poor design, suffocated 32 infants. Thanks to the investigation, a recall was issued for the baby seat and it was redesigned. I had never thought of his work this way, but, as one of his colleagues pointed out, even that one report had likely saved hundreds of infants’ lives. “He probably saved thousands of lives over his career,” another colleague said. What he did was really the bread and butter of CR journalism: they regard themselves as something like the watchdogs of the FDA; one of their rare bylined articles was by Ralph Nader, in a piece related to his book Unsafe at Any Speed, whose work led to seatbelts in cars being legally required and culturally normalized.

In his honor, I want to be a better member of my own editorial team, and a better journalist.

He and my aunt, and their three kids, always embodied to me a particular way of being that I admired: they’re all fully engaged with life, pitching in, doing projects. There were always projects: cords of wood to be split, outbuildings to be built, paths to lay out in the wild poison ivy-ridden area below the dam at our family’s lake house. He loved plans, the more elaborate the better, and he loved planning adventures for his family. He would get ideas - for a meal, for a road trip, for keeping chickens - and never be put off because an idea was too much trouble, too much of a schlep, too much effort. He put enormous effort into all parts of his life, and that blessed all of us. He followed through. But the effort never felt grim: it was joyful effort, even playful.

I can’t write everything: there have been some beautiful and wonderful parts of this that are too precious and family-private to write about. I love him so much. I am so grateful for him and for the family.

Other News

Our Winter issue is out! Educating Humans is packed. Highlights:

The Bruderhof school’s showdown with the SS, in 1933, led them to re-locate all their school-aged kids to the Alps of Liechtenstein, to prevent them from getting forced into Nazi schools and indoctrinated.

The American College of Building Arts, in Charleston, South Carolina, is a school for philosopher-carpenters, aiming to recreate the educational model of the Medieval trade guilds.

Teaching literature and writing in an age of AI: Phil Christman makes a plea for the ongoing importance of the human as opposed to the robotic English teacher.

A high school science teacher uses the forests and waterways of Upstate New York as his classroom.

Rabbi Meir Soloveichik gave the graduation talk for the Bruderhof’s high school, telling them about the time Joshua Bell played his Stradivarius in the New York subway.

Once a year, it’s Lernvergnügenstag: a “day for the joy of learning”, when curricula go out the window, teachers offer middle schoolers seminars in whatever they most want to teach, and students choose among the seminars based on what they most want to learn.

I did an interview with Peter Gray, whose life’s work has been the defense of children’s free play in a world of increasing supervision and safetyism.

Check out the issue - there’s a lot more too!

Alastair: I posted an update on my news less than two weeks ago, so do not have much to add here: this post is largely devoted to Susannah’s news. In the week following our last Substack post, I had a relatively typical yet busy week of work and continued to settle back into life in New York. We also started to prepare for Christmas, including braving mindnumbingly awful Christmas songs to purchase decorations and items for Christmas creations. [Susannah: We went to Michael’s, the craft store, and I think Alastair is a little traumatized.]

We had a friend to stay overnight on Friday. On Saturday night we joined Hannah Long and some other friends to watch Terrence Malick’s astonishing 2005 film, The New World. I had seen it several times before, although it was Susannah’s first time. Indeed, it was her first time watching any Malick movie. She will definitely be watching more!

After church on Sunday, we met up with some friends for a meal. Later that afternoon, I left for Newark Airport, from which I flew down to Greenville. The last couple of days I have been with my great friend Joseph Minich at the latest ‘Congregational Life in a Digital Age’ gathering. Over a year, several pastors in the area are joining a group to talk through a series of texts relating to technology, society, and the Church, in a project co-ordinated by the Davenant Institute.

For this event we were staying in a house on the top of White Oak Mountain, the first peak of the Blue Ridge Mountains. When not obscured by heavy clouds, as it was for much of the time, there are stunning views over the surrounding countryside, although the drive up was certainly hairy at various points!

During this session, we discussed Artificial Intelligence, techno-optimism, our changing experience of reality online, and a large range of topics flowing out from these, using a few set texts (such as Jon Askonas’s The New Atlantis ‘What Happened to Consensus Reality?’ essay series) to stimulate and shape our conversation. The group of pastors are wonderful people and, beyond the formal discussion time, we enjoyed many stretching and encouraging conversations.

Tomorrow—I am writing this on Tuesday the 10th—I fly back to New York, where I am speaking at an event in the evening at Hephzibah House.

Advent Hermeneutics

I have been revisiting the subject of hermeneutics recently. A few days ago, we recorded our penultimate episode of Mere Fidelity before our forthcoming hiatus, Kevin Vanhoozer joining us to talk about his superb new book, Mere Christian Hermeneutics: Transfiguring What It Means to Read the Bible Theologically. A quote from the Pentecostal New Testament scholar Gordon Fee was also circulating on social media around the same time: “A text cannot mean what it could never have meant for its original readers/hearers.” These two things both provoked the following thoughts, which were also considerably coloured by just having begun the Advent season.

Fee’s statement seems to be designed to defend something important. It is evident that there are interpretations of Scripture that seem to impose alien meanings upon texts, meanings that cannot be sustained by the actual sense the words have in any proper context, which do not arise organically from them, and which wrest the words away from the original historical context within which they were given. Those of us who take the meaning of the Scriptures seriously do not want to do violence to it, nor to impose our own meanings upon it. Statements like Fee’s are often provoked by concerns that the text retain the integrity of its voice over against us, that people not ventriloquize their own favoured or fancied meanings into the word of God. Yet, despite Fee’s clear good intentions and the necessity of addressing such errors, to my mind his statement misses the mark in various ways.

At the outset, it should be noted that I am focusing upon a single and isolated claim of Fee’s, which is far from the entirety of his extensive thought on such matters. Elsewhere in his work, one finds evidence of a more nuanced and sophisticated account of hermeneutics, which addresses some of the issues that I raise in what follows. My purpose here is not to engage with Fee in particular, but rather to take his statement—a statement that represents a commonly held judgment—as a springboard for a consideration of some principles of biblical hermeneutics more generally. In many respects, the quoted statement of Fee is representative of the sort of statement one would expect from interpreters committed to a grammatical historical hermeneutic, concerned to read texts in their original literary and historical contexts.

While such an approach seems commonsensical to many, it is not without its problems. The Apostle Paul, for instance, throws something of a spanner in the works in places like 1 Corinthians 10:11, when he writes: “Now these things happened to them as an example, but they were written down for our instruction, on whom the end of the ages has come.” Such a claim unsettles the presumed primacy of the original audience. It suggests that the narrative of the Exodus, while serving a purpose for its first hearers, was written chiefly with a future audience in mind. Indeed, Paul suggests that even the recorded events of the Exodus themselves occurred in anticipation of a later community who would undergo a homologous yet greater deliverance, the historical account exemplary and instructive for them.

Understood in such a manner, the ‘original audience’ should have perceived the historical narrative of the Exodus to have something of a prophetic character, its greater import yet veiled. When the anticipated greater Exodus occurred, the historical account of the first Exodus would be read in a new light, its meaning unfolding in dramatic ways. The deliverance would not merely be an awaited redemption, but an event of hermeneutic disclosure.

The Apostle Peter makes a similar point to Paul’s in 1 Peter 1:10-12—

Concerning this salvation, the prophets who prophesied about the grace that was to be yours searched and inquired carefully, inquiring what person or time the Spirit of Christ in them was indicating when he predicted the sufferings of Christ and the subsequent glories. It was revealed to them that they were serving not themselves but you, in the things that have now been announced to you through those who preached the good news to you by the Holy Spirit sent from heaven, things into which angels long to look.

Of course, while the words of the prophets may principally have been recorded to serve the Church, they served to encourage the faithful of old to strain forward in hope, longing, and expectation for the awaited redemption, diligently investigating and considering the anticipatory revelation they had received.

In a previous post, I commented upon the importance of time in Christian interpretation and the degree to which it is commonly neglected. This is doubtless true when it comes to hermeneutics, for which implicitly or explicitly spatialized metaphors can often be dominant. The ‘meaning’ of a text is spoken of as something that is not conditioned by or changed over the passage of time. Perhaps there are different later ‘applications’, or maybe a new ‘layer’ of meaning is built upon the original, but the notion of the meaning of a text itself undergoing changes can give conservative Christians the collywobbles.

Now, as I have noted above, their concerns here are understandable and, to a large extent, justified. If the meaning of a text were to develop in ways that undermined or radically subverted their original sense, there would certainly be grounds for legitimate concern. I hope that, as we think more carefully about what is in view here, its character will seem much less unsettling.

What I am discussing should not actually be overly difficult to understand, as the principles here are much the same as those that apply to a host of other texts and situations, even if we are dealing with a special case. The Holy Scriptures may be a more pronounced example of certain dynamics, but the dynamics themselves really are familiar.

Let us consider a few illustrative cases.

First, reading—or, perhaps better, hearing—poetry, one will often find that the meaning of a poem arrives over the course of its performance. There will be phrases or expressions that hang unresolved in the air, ambiguous until later lines disclose their true sense. Sometimes a poem wrongfoots you; a word you instinctively took with one sense is revealed to have a different unexpected one, forcing you to reinterpret. Yet the ‘meaning’ of such expressions is not merely their final resolved sense, but includes the earlier unresolved ambiguities.

People talk about the importance of considering ‘context’ in order to discern meaning, yet often fail to appreciate its temporal character, conceptualizing it in a more spatialized fashion. Context, however, is something that often unfolds through time and we will appropriately read or interpret that which comes earlier in terms of that which follows, or that which is anticipated to follow. Likewise, because of the nature of time, we can significantly reevaluate something if a text, a narrative, or events move in a different direction from that which we anticipated. This is little more than a common species of reading in context and the way in which the meaning of something is in large measure contingent upon what surrounds it, both ‘spatially’ and temporally.

Second, we might consider the experience of listening to a truly sublime symphony or opera, composed by someone of surpassing genius and goodness. The ‘meaning’ of the music is constantly arriving, never fully present. Throughout, while delighting in the glory of what has arrived, you are anticipating more.

You probably do not know how the composer will resolve everything, but even in the most difficult passages, you can be confident in the composer’s achieving a resolution that will be both surprising and moving in its effectiveness. The ‘meaning’ of such a piece can only truly be known by submitting oneself fully to—and participating in—a process of disclosure.

Third, when reading a novel, perhaps especially something like a detective novel, second and later readings of a novel will be shaped by our knowledge of its final dénouement. When we know where the narrative is going, it rightly shapes our reading of earlier passages and provides a rule for reading them. The earlier passages must be read in light of and towards the ending. They are not brute textual realities, but ordered towards the resolution. Likewise, on our first read of a novel, our reading will constantly be shaped by anticipation and speculation. We know that the novel is working towards a conclusion and that details that initially seem insignificant or confusing to us will likely make sense by the end. We might say that we ‘do not yet know what they mean’, although we also recognize that they are also purposeful in the more immediate context in the narrative where we first encounter them. They might be intentional clues or misdirection on the part of the author, for instance: the meaning is not merely what they are in light of the whole.

Holy Scripture operates in much the same way. Its meaning unfolds through time in a way that is beautiful. We should revisit earlier parts of Scripture in the light of what follows and read or reread them accordingly. This approach to reading naturally gives rise to the quadriga or fourfold sense of Scripture.

As we take the process of unfolding seriously, we take the literal and historical sense seriously. Among other things, this involves concern to preserve some sense and integrity of the meaning to the ‘original audience’, even as we might recognize a primacy to the meaning as it appears to the ‘final audience’, to those who perceive earlier events in the light of the whole narrative. For instance, following the example of Rabbi David Fohrman, I often encourage people to read certain texts while presuming that they did not know what happened next, asking them what they would have expected to follow. Such a practice makes us more attentive to the process of progressive unfolding, in ways that prevent the vantage point provided by the final conclusion from blinding us to the actual movement of showing. Readings like this, however, are never the final readings, but are always provisional readings on the way.

As the story climaxes in the coming of Christ, allegorical reading is necessary—it is all somehow about him and must be read towards him. Taking this seriously, and along with a robust doctrine of divine inspiration, we will not satisfy ourselves with treating Old Testament Scripture as a mere historical record, but will be searching for the ways Christ is revealed and anticipated throughout.

As the story is about the formation of a new holy people, ultimately formed in Christ, it must all be read tropologically. As Paul read the narrative of the Exodus as a narrative of Christ, he also read it as a narrative designed to lead the Church into holiness of life.

As the story ultimately is resolved in the new heavens and new earth, with the descent of heavenly realities, it must also all be read anagogically. In this regard, the full sense of the Scriptures is still awaited, even if truly seen afar off, especially as a foretaste has been granted us in Christ’s first advent and the gift of his Spirit. We recognize that heavenly, future, and Spiritual realities are prefigured in this age in earthly and fleshly ones. There remains an element of mystery here and, much as the saints of old might have reflected upon the words of the prophets, pondering what form of fulfilment they might have, so we read much of Scripture uncertain about what the age to come will involve, yet confident that it will bring with it a sense of profound disclosure, recognition, and resolution.

Understood in such a manner, the fourfold sense of Scripture is not some weird or alien hermeneutical imposition upon the text, but the application of relatively commonsensical principles of interpretation to a text whose unity is found in the Lord of history who inspired it and orchestrated the events recorded within it.

It might be worth thinking about what this means when applied more specifically. For instance, the book of Joshua—the account of the conquest of Canaan—if it is to be read as part of the canon of Scripture, must be read as ordered towards the end of the Scripture and its narrative. An emphasis upon the literal sense of the book ensures, among other things, that its initial force be taken seriously, to some degree carried forward, and not retrospectively overwhelmed, fundamentally subverted, or merely discounted.

Yet we know that it must be read as a part of a profoundly unified story that leads to Christ. The literal sense of the text cannot be held as profane and secular—merely a religious account of Late Bronze Age wars in the Ancient Near East, even if part of a history into which Christ might come at some later point—but must bow to Christ. Truly to understand the book of Joshua, we must interpret it as being about Christ. ‘Typology’ is a recognition that history is prophetic and that events such as the conquest of Canaan find their principal referent in later events. As New Testament texts such as Acts, Hebrews, or Revelation all evidence in different ways, the events of Joshua were interpreted by the earliest Church as being about Jesus and his deliverance; the very name Jesus hearkens back to the leader of the conquest.

The narrative of Joshua also needs to be read as something ordered towards the holiness of the people of God, written for their moral instruction, and in some manner exemplary for them. Again, it is not enough merely to maintain that it is not fundamentally at odds with our moral formation—to be able to defend Christian ethics from the book of Joshua as if from a threat. In some manner the text must serve and ‘be about’ our holiness. Likewise, it must also be a narrative ordered towards and consistent with the final dénouement of the Scriptures in the new heavens and the new earth. The Promised Land anticipates a greater promise, of ‘new heavens and a new earth in which righteousness dwells.’

Read superficially, the book of Joshua may not seem to invite such readings. However, such readings are not merely permissible, but required of us, if indeed we are to read Joshua as Holy Scripture and take its unity and the unity of the divine purpose seriously. Were we to detach Joshua from Holy Scripture, one could perhaps imagine it being the first phase in the story of a rise of a militaristic empire. Read in light of such a story, we would accentuate facets of Joshua that reading it in light of Christ will tend to downplay.

Considering these neglected dimensions of hermeneutics, part of what our hearing of Scripture needs to recapture is a posture of longing and expectancy, and a practice of alertness to the distant horizons of the text. We need to hear Scripture in the season of Advent, as it were. Seeking the meaning of any passage of Scripture requires us to have a sense that the meaning has not yet fully been revealed, even if we already see something of the final form of it in Jesus and the holiness of life imparted by the work of the Spirit. This should yield a longing ‘Maranatha!’ as a natural hermeneutical impulse.

Advent Absence

Jim Salladin, the rector of our church in Manhattan, is one of my favourite preachers. Over the last couple of weeks, he has been focusing upon Advent themes, working with the book of Haggai in particular. Had I been tasked with choosing a book to focus upon over Advent, Haggai would not have been my first choice. However, Jim’s sermons have provided a strong case for it.

Haggai challenged the returned exiles of Judah to commit themselves to the task of restoring the temple. The Babylonians had destroyed Solomon’s Temple and, while the people had returned to Jerusalem several decades after the fall of the city and were in the process of rebuilding their own houses, the temple remained in ruins. Within the book of Haggai, as Jim has emphasized, the Jews’ failure to rebuild the temple was akin to foreclosing the story of Advent.

In his sermons, Jim has brought out a variety of elements of the book. However, this observation and line of consideration particularly grabbed my attention. In Haggai 2, the prophet tied the rebuilt temple to promises of future divine coming in blessing and judgment. While the Lord filled the tabernacle after its construction at the end of Exodus 40 and Solomon’s Temple at its dedication in 1 Kings 8:10-11, no comparable event is recorded of the post-exilic temple. Rather, a promise is giving of a future awaited filling in Haggai 2:6-9:

For thus says the Lord of hosts: Yet once more, in a little while, I will shake the heavens and the earth and the sea and the dry land. And I will shake all nations, so that the treasures of all nations shall come in, and I will fill this house with glory, says the Lord of hosts. The silver is mine, and the gold is mine, declares the Lord of hosts. The latter glory of this house shall be greater than the former, says the Lord of hosts. And in this place I will give peace, declares the Lord of hosts.

The post-exilic temple, then, rather than representing the continuation of a historical theophany, as the institution of the tabernacle continued the theophanic event of Sinai, was a symbol of an awaited coming of the Lord, a site defined more by anticipation and hope than by memory. Haggai, of course, is not the only place where the temple becomes a focal point of expectation. Isaiah 2 speaks of the nations going up to the mountain of the Lord in the latter days. Ezekiel describes an eschatological temple around which the nation would be reformed and from which cleansing waters would flow. Malachi declares that the Lord would suddenly come to his temple (3:1-4), purifying its worship and bringing judgment.

Throughout their history, the tabernacle and the later temples were an ordering, training, and elevating of the gaze of the people of God. In Solomon’s prayer of dedication for his temple, for instance, we find an implicit theology of the temple, as he is careful to distinguish the pedagogical symbolic presence of the Lord in his earthly temple from his actual being. 1 Kings 8:27-30—

But will God indeed dwell on the earth? Behold, heaven and the highest heaven cannot contain you; how much less this house that I have built! Yet have regard to the prayer of your servant and to his plea, O Lord my God, listening to the cry and to the prayer that your servant prays before you this day, that your eyes may be open night and day toward this house, the place of which you have said, ‘My name shall be there,’ that you may listen to the prayer that your servant offers toward this place. And listen to the plea of your servant and of your people Israel, when they pray toward this place. And listen in heaven your dwelling place, and when you hear, forgive.

When we speak of God ‘dwelling’ in the temple, we must recognize the improper sense of such terminology, while also appreciating the importance of the ordering of Israel’s worship, understanding, life, and affections through the Lord’s express commitment to it as his ‘house’. After the exile, however, while some sense of the Temple as God’s dwelling place clearly remains, the temple increasingly functions as a symbol of promised and awaited Advent. There is a movement from the Lord being regarded as dwelling in his temple to the Lord having promised to come to his temple.

As such, the ‘presence’ to which the Jews were ordered was reinscribed in a symbol of absence. Whether in the Israelites’ treatment of the Ark of the Covenant at the Battle of Aphek at the beginning of 1 Samuel, or Judah’s trust in the temple evidenced in the prophet’s sermon in Jeremiah 7, there was always a danger of the temple producing an immanentized sense of the Lord’s presence, placing God in a bottle, as it were. The post-exilic temple was less susceptible to this.

The temple continues to be extremely important in the New Testament, but the symbol of the Temple undergoes further clarification, being connected with the body of Christ and the Church, for instance, and treated as a symbol of a heavenly reality. In this process, our gaze is elevated and focused. The eschatological sense of the Temple’s significance that becomes more prominent in the post-exilic period is developed. Indeed, the destruction of the physical building of the Temple that Jesus declares and which the events of his death anticipate is a continuation of this process of purification of vision.

Although the physical building and fleshly sacrifices of the Temple have now been removed, the ordering and the movements that they informed and guided continue and are intensified as they are both more humanized and more Spiritualized (the capitalization being important here). And the Advent significance that came into clearer view in the Second Temple period has only increased in its importance. In many ways, the Church, an assembly and community described as a new temple, must be keenly aware of absence at its heart. This absence is not a hollow, inert, ambiguous, or miserable emptiness, but a space crackling with expectancy, longing, and desire for the One who has promised to come to us. In the Advent season, we should attend to this absence and feel it with a renewed keenness, an absence for whose form Christ’s coming could be the only fitting answer.

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ Mere Fidelity is nearing its hiatus. Derek, Matt, and I had a conversation on Richard Hays’s new book, The Widening of God’s Mercy, and the controversy surrounding it. Kevin Vanhoozer also joined us to talk about hermeneutics; his latest book, Mere Christian Hermeneutics: Transfiguring What It Means to Read the Bible Theologically, has just been released.

❧ The end is now clearly in sight for Theopolis Podcast’s Deuteronomy series. Our latest episode is Deuteronomy 33: Moses’ Final Blessing on Israel, Part 3.

❧ In anticipation of my forthcoming course on the psalms, I recorded a version of my reflection Psalm-Singing and Our Encounter with Scripture

❧ Susannah, Rhys Laverty, and Jake Meador joined me for a discussion of the recent Davenant Press book, Life on the Silent Planet: Essays on Christian Living from C.S. Lewis’s Ransom Trilogy, to which they all contributed.

Upcoming Events

❧ Alastair will be at the Theopolis Fellows Program in Birmingham, Alabama from the 12th to the 18th January.

❧ Alastair will be speaking at New College Franklin on January 20th.

❧ Alastair will be speaking at Hephzibah House this evening (December 11th).

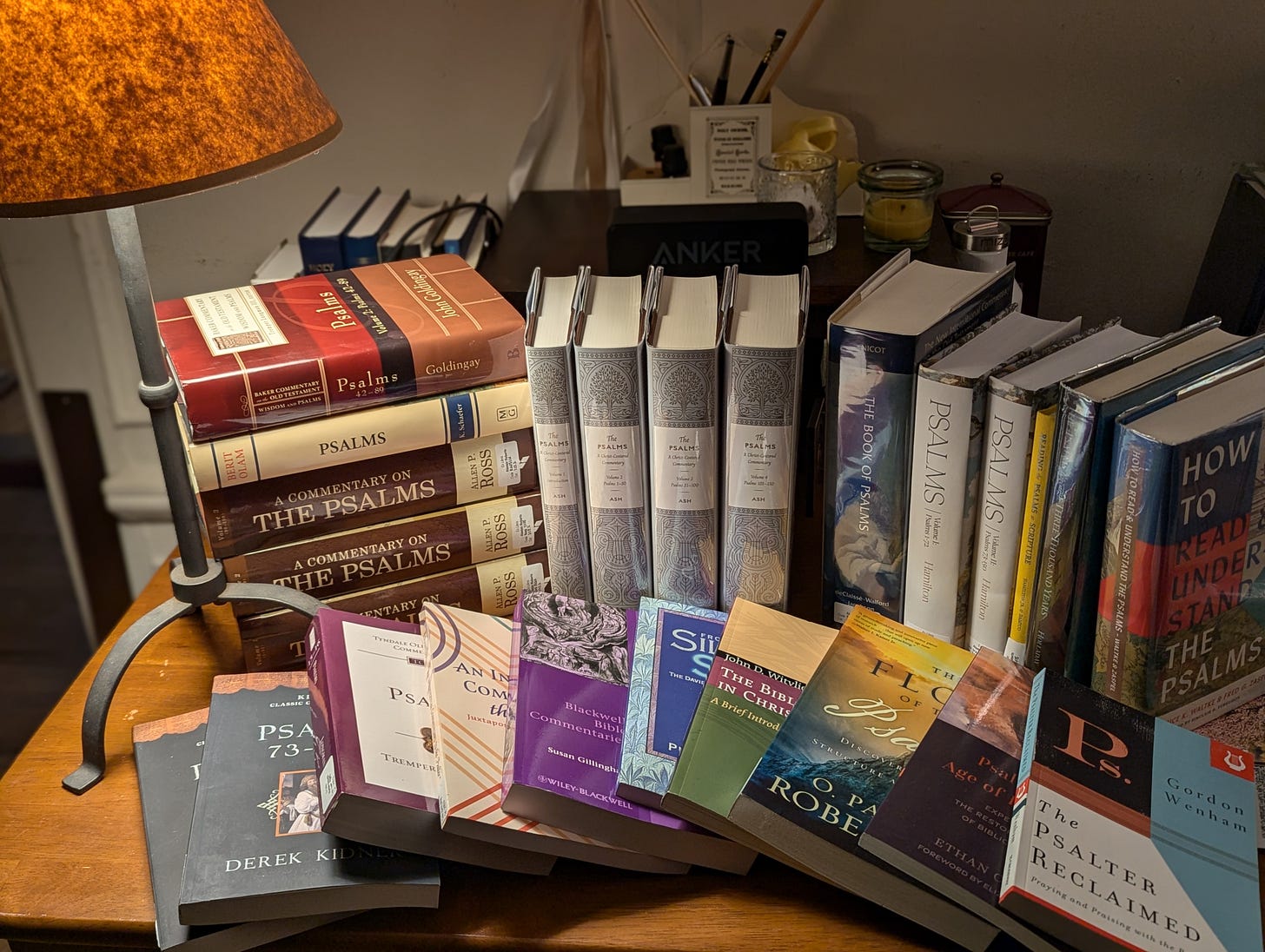

❧ Alastair’s next Davenant course, ‘The Psalms: A Bible in Miniature’, is now available for registration:

In his introduction to his lectures on the Psalms, Martin Luther described the Psalter as ‘a little Bible’, declaring that ‘in it is comprehended most beautifully and briefly everything that is in the entire Bible.’ For nearly three millennia, the psalms have been at the heart of the worship of the people of God. This course will consider the place of the Psalter within the scriptural canon and the life of the Church and its members. It will equip students to read and, more importantly, to sing with greater understanding and benefit. While deepening students’ appreciation of individual psalms, this course aims to give students a firmer theological grasp upon the role and use of the Psalter as a whole, its ordering to Christ, and the ways that it can transform our relationship to Holy Scripture more generally.

You can see the syllabus here: this will be a really deep dive into the Psalms and the literature surrounding them.

❧ Much of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Alastair and Susannah

So, just to be clear, this is what a post mostly dedicated to Susannah looks like?

Seriously though, very helpful and interesting reflections all around. I'm most excited, however, about the introduction to Mallick's films. I was slow to appreciate them, but I love most of what I have seen and consider "Tree of Life" perhaps the best film ever made.

"The New World" is profoundly humane. One of my favorites.