№ 41: A Marseille Visit

Also retrieval, infohazards, voting and virtue ethics, and being prepared to 'die'

Alastair: Over the summer, my brother Mark turned forty. To celebrate the milestone, Mark invited me and our other two brothers to spend a week with him in the South of France, where he lives with his wife and their two daughters, Jane and Olivia. Our youngest brother, Peter, was unable to make it, but my brother Jonathan travelled from Hamburg and I came over from the UK.

The last time I visited Marseille was on the second week of our honeymoon. We had spent the first week in Vienna and had failed to book an Airbnb for the night of our arrival in Marseille, so stayed with my brother and his family before travelling on to Cassis, where we spent the next week. That was also the first time that I had met my new niece, Olivia. She is now an energetic and chaotic three and a half years old. Time flies!

We had originally planned to spend the week exploring Corsica, but we ended up changing our plans, choosing to stay in Marseille instead and visit some surrounding cities and other locations. This worked out for the best: besides saving us money, it allowed us to spend some time with my sister-in-law and two nieces, to have a more varied itinerary, and also meant that I was able to worship with them at the church they attend.

The weather was truly glorious—warmer than most British summer days, even at the beginning of November—which enabled us to get a lot of walking done.

I arrived into Marseille late on the Sunday evening. Jonathan, Mark, and I began the next day by walking much of the way into the centre of Marseille from their apartment. We spent a couple of hours around the Old Port and Noailles, buying gifts and seeing some sights.

We had considered visiting Château d’If, but it was not open for visitors, so we took a boat out to the Frioul archipelago, passing the château on our way.

After a meal near the harbour, we climbed up to the fort at the top of the island, from which we enjoyed spectacular views out over the sea, the coastline, and the other islands.

There was a complex of old military fortifications, gun emplacements, and collapsed buildings on the site, which had formerly served to defend Marseille harbour. Many of the fortifications had been built by the Nazis during the Second World War, which added a further layer of interest.

We had a few hours before we our return ferry departed, so we explored the area thoroughly, venturing into some tunnels and climbing and clambering around the ruins. There were several dramatic vistas to be enjoyed from some of the vantage points our route afforded us.

After a couple of hours of walking, we crossed over to the connected island, although, with the light fading and our departure time rapidly approaching, we were not able to get to the lighthouse we had hoped to reach. We did pick some cactus, though. The next day Jonathan cooked the cactus and we also ate some of its fruit. I had tasted neither before and, although they were not anything to write home about, they were quite palatable.

The following day we all went to the Alpilles National Park and Les Baux-de-Provence. It was my niece Jane’s birthday, so we met up with her grandparents for a day out.

We started the day by visiting an old bauxite mine, a cavernous space with immense walls, all carved out of the rock. The mine has been converted into an immense light show, with a dramatic and awe-inspiring series of displays projected onto its surfaces. Having attended Durham’s Lumiere festival on numerous occasions, I am familiar with such dramatic light displays, but had never seen anything on such a scale. I am not aware of any comparable attraction elsewhere.

There were displays on the Egyptians and on famous artworks, among other things, all accompanied by music and other sound effects. We were all quite amazed by the spectacle!

After leaving the mine, we found a location for a picnic and had some birthday cake for Jane. Having finished our picnic, we then walked back into the maze of rocks and trees that lay behind our picnic spot, climbing some of the rocks with the kids.

Not far from the mine is a castle, situated on a commanding rocky outcrop, standing sentinel over the Les Baux valley. From our picnic spot, we made our way up to the quaint mountain village, through whose narrow and winding streets one could ascend to the castle.

The scale of the castle and of the landscape in which it is situated, is difficult to convey in words or capture in pictures. To get to the different parts of its higher levels, we needed to ascend staircases up the soaring rockface. The vertiginous height was dizzying, but the views were remarkable.

On one side of the castle was the village, from which you could descend into the Val d’Enfer, so named because Dante took inspiration from it for his depiction of hell in his Inferno. On the other side was a large expanse of lush fields and vineyards, stretching out to the horizon.

Mark returned to the entrance to the village with Alice and Olivia, but Jonathan, Jane, and I spent a little more time exploring the castle, before rejoining them, after which we drove home.

All my brothers are active outdoorsmen, but Jonathan, who is perhaps the most active of us, wanted to run across the mountainous route of the Calanques from Marseille to Cassis. The next day he set out earlier, while Mark, Jane, and I had a more leisurely start to the morning and drove along the coast to Cassis.

Cassis was the place where Susannah and I had enjoyed the final part of our honeymoon, so it naturally holds a lot of happy memories. Had she planned things a little more carefully, she might have been able to join me for the trip. [Susannah: I’m reading every word of this draft, you know.] I made sure to remind her of this regularly, sending her pictures of and making video calls from some of the more picturesque places we visited over the week!

Cassis is a delightful seaside town in the Calanques, with stunning scenery, lots of places to hike and walk, a large market, and the beauty of the Mediterranean, scintillating beneath a brilliant sun. While waiting for Jonathan to arrive, I looked around some of its streets, reminding myself of our honeymoon.

I bumped into Jonathan while wandering around and then we joined Mark and Jane on the beach, where Jane had been swimming. After a little while longer on the beach and a long wait for the bus, we drove back to Marseille.

On the Thursday, Alice, Olivia, and Jane joined Jonathan, Mark, and I for a trip to Aix-en-Provence, which I had not visited since Mark and Alice’s wedding. They used to live in Aix, so I was familiar with the place, but was delighted to have the opportunity to see it again. We spent the first hour or so looking through the market, where I managed to find a replacement tablecloth for one Susannah and I had bought during our honeymoon, but which had been damaged.

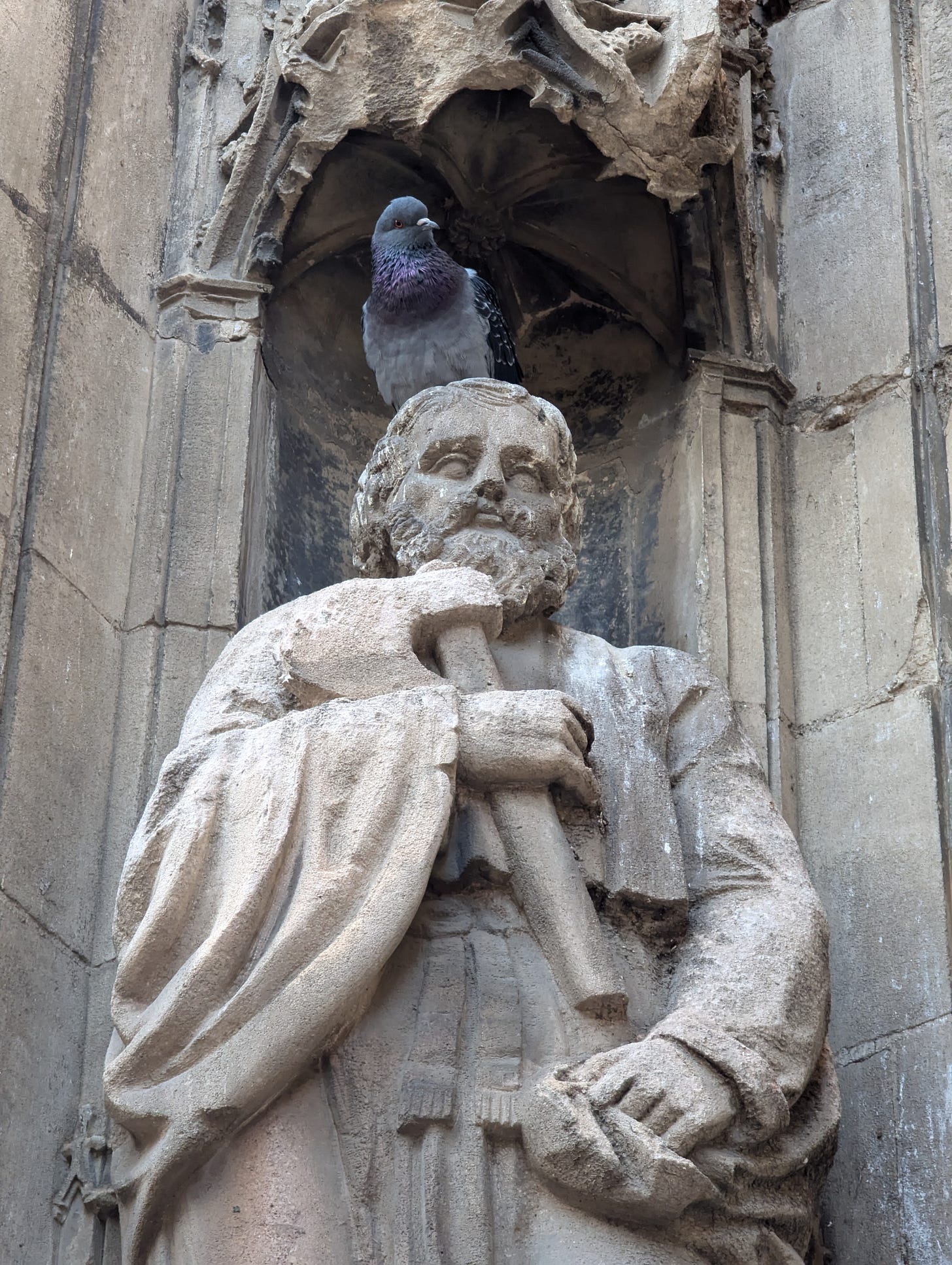

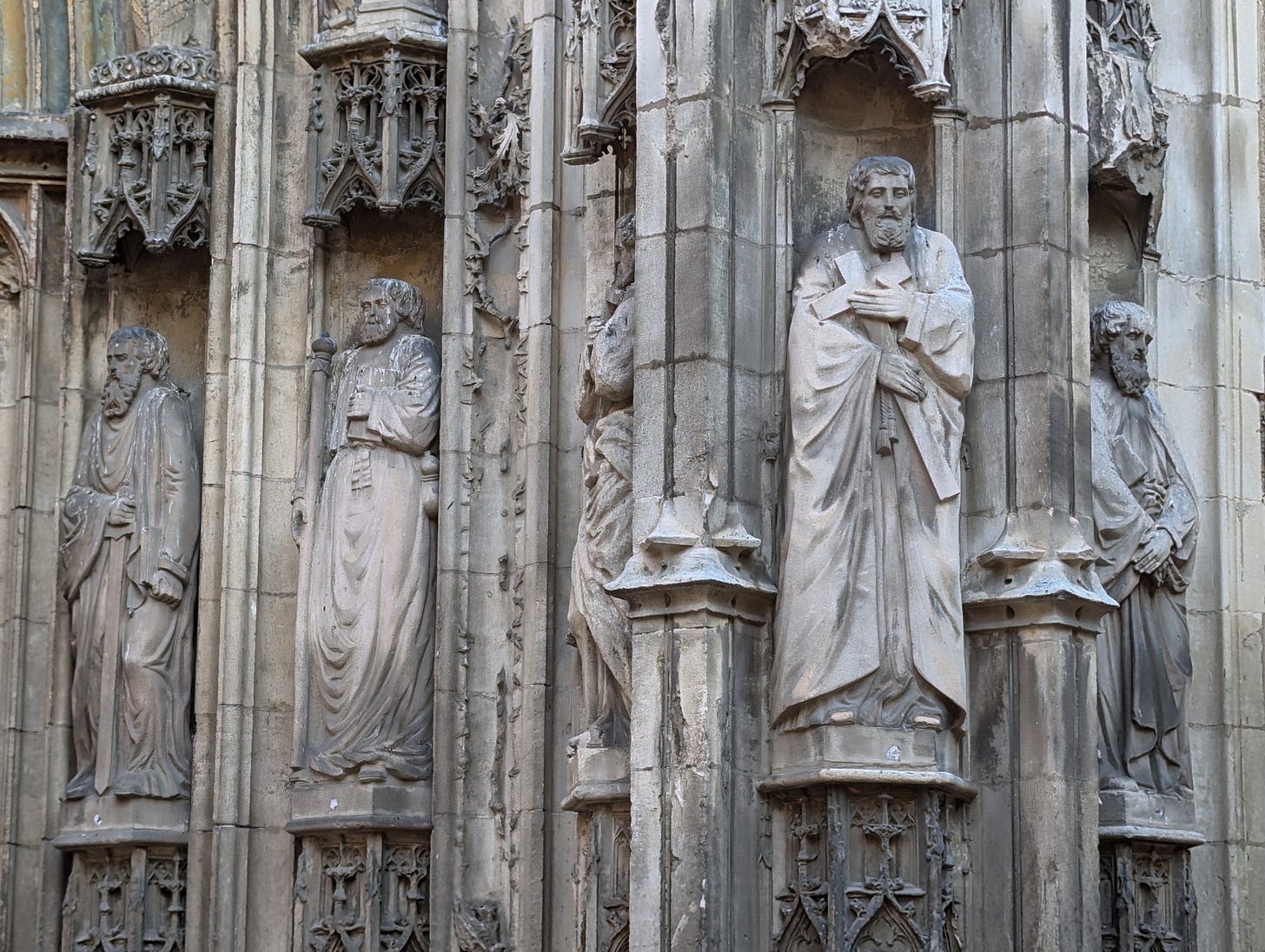

From the market, we had a meal at an incredible Israeli restaurant, explored a church, visited a couple of bookstores for Jane (who definitely has the Roberts bibliophile gene!) and enjoyed a coffee. Jane got her face painted, and then we visited the cathedral.

Susannah is long-suffering with my incessant urge to comment upon the architecture and town-planning of every place we visit. In her absence, my brothers had to suffer my remarks, but Aix is a beautiful city and, like many such places, benefits from the fact that much of it is quite inhospitable to motor vehicles. In my experience, once you start to notice this, it becomes clear that it is a common theme for many of the most attractive places one can visit.

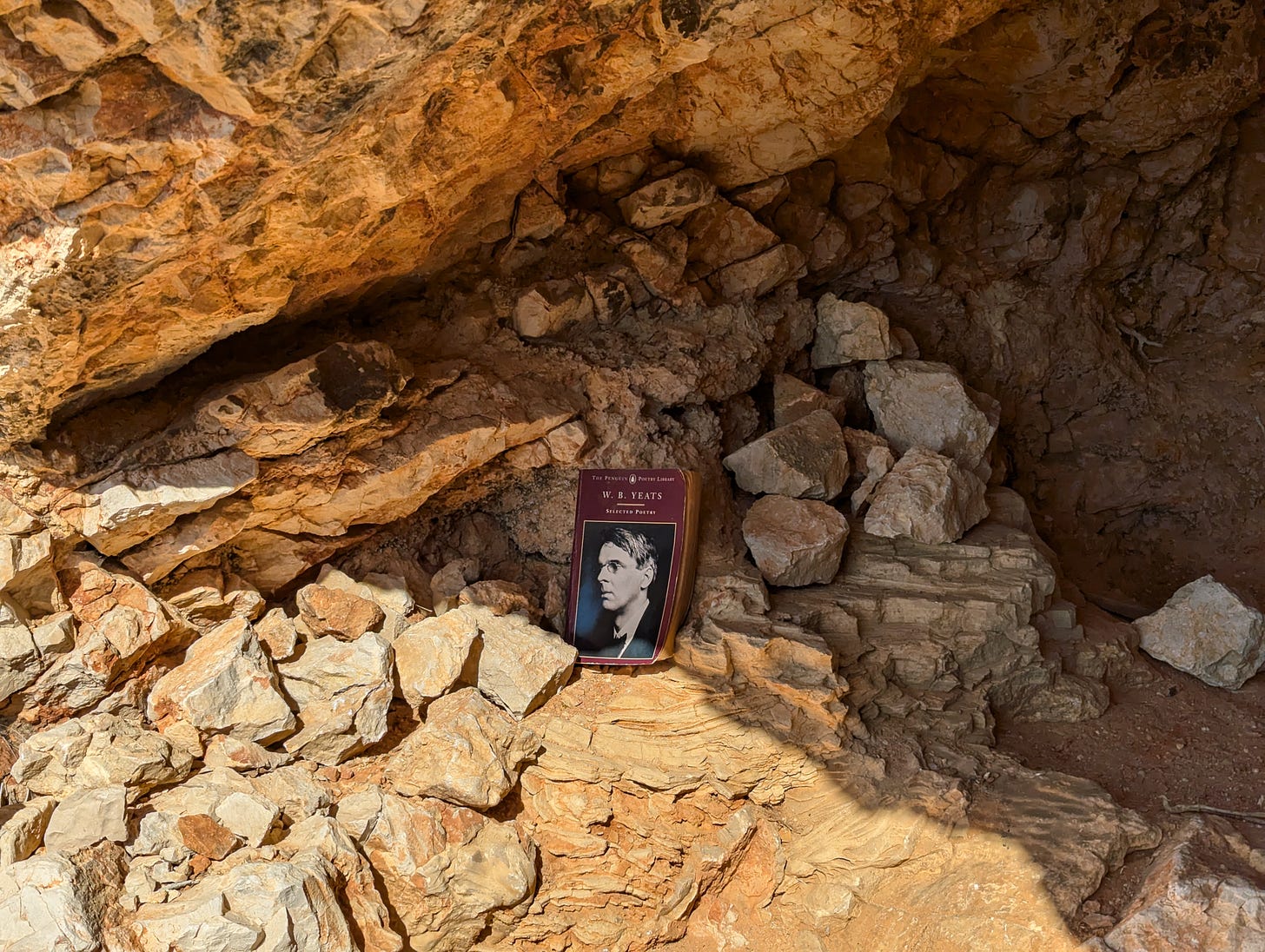

The next day Jonathan was taking things easier in the morning, so Mark and I went out to explore one of the nearest calanques to them, in Sormiou. Hiking over the top of the calanque, we had incredible views down into two coves. We then descended down into one of them, where we happened upon a small cave in the cliffside.

Surprisingly, we found that a thoughtful visitor had left a copy of selected poems of W.B. Yeats within it. We enjoyed a pleasant break in the cave, before climbing back up and returning to the car.

We passed the afternoon more quietly. Jonathan wanted to run out to Pointé Rouge, where we planned to meet to watch the sunset.

As we were late setting out, when we arrived Mark and I were hard pressed to climb up to the clifftop lookout point before the sun went down. However, scrambling up as fast as we could, we managed to make it in time and had a spectacular view from a splendid lookout point. The thrill of the height and the adrenaline of the dash to get there only added to the experience.

As things got darker, we climbed back down, meeting up with Jonathan again at the bottom. He had climbed high up on the Calanques, which, with the decreasing light and visibility, proved to be quite a hairy experience at certain points! We then drove back, meeting up with Alice and the girls on a beach near their apartment.

After full days of walking and exploring, I had quite a lot of the evenings free and space to myself, so I was able to get a fair amount of work done over the course of my trip. On the Friday evening, for instance, I taught my class for Davenant.

Jonathan returned home to Hamburg on the Saturday morning and, after dropping him off at the airport, Mark and I drove out to Nîmes, which I had not yet visited. Nîmes is a fascinating city. It was an important site in Roman times and has several Roman buildings of immense size, most notably its coliseum, which, to my knowledge, is the best-preserved building of its kind and still in regular use.

While on the way to Nîmes, I was informed that the first of my biblical reflections had been translated into French, which was exciting to hear. Lord-willing, over the next few years the entirety of my biblical commentary will be released in French.

Arriving in Nîmes, we went straight to the coliseum and devoted a couple of hours to exploring it.

The coliseum took longer to explore than I had expected. While I have seen countless impressive Roman ruins over the years, I cannot recall having had the experience of walking around a Roman building of remotely comparable proportions of in such good repair. At many points one could imagine oneself back in Roman times, ascending the stairs and passages, to come out into the din of a vast crowd surrounding the arena.

We walked the entire circuit of the upper levels of the coliseum, before descending down and going out into the arena.

Directly opposite the coliseum was a hotel and café, surrounded by a large seating area. Mark and I both ordered a Viennese coffee—sparking other memories of our honeymoon—and enjoyed the view. Behind us was the coliseum. On the table next to us a group of soldiers in the French Foreign Legion sat down. Around us, people were reading newspapers, or walking beneath the shade of the trees by the café. Even besides the coliseum, the architecture surrounding us was glorious. It was a welcome reminder that civilization still persists in some isolated pockets.

After finishing our coffees, we went to explore more of Nîmes. Although we did not go into the Maison Carrée, we went to its square and walked around it. We had been toying with the idea of visiting Avignon, but decided to leave Avignon for another day, choosing instead to go through the park to the old Roman tower at the summit.

It was my first time visiting Nîmes, and Mark had not explored much of it, so it was a real treat for both of us. Going up through the park to the tower in the late afternoon light was very special. We came across a man playing the hurdy gurdy on the way; it turned out that he was not a busker, but just wanted to play in the surroundings of the park.

The tower had needed to be rebuilt after its foundations were dangerously compromised after someone had dug beneath it, believing that a prophecy of Nostradamus indicated it was the site of some hidden treasure. Now it has a spiral staircase at the centre of it, ascending to the top, from which you can look out over the entire city.

After an Indian meal—at Mark’s request, as Indian food is less common in French—we drove back to Marseille.

Sunday was my last full day in Marseille and we took it very easily. After church in the morning and a meal, we lounged around for much of the rest of the day, reading, playing boardgames, and enjoying time with Olivia and Jane.

It was a huge blessing to have such time with Mark and Jonathan, and with Mark’s family. My brothers and I have always been close and, although we live in different countries, whenever we spend time together, I feel a renewed sense of immense gratitude for them and the bond we continue to share.

After all the activity of the Marseille trip, the subsequent time has been quite noneventful. I have mostly been writing, reading, producing various podcasts and videos, teaching classes, supervising student projects, and generally engaging in the typical quotidian activities of life in Stoke-on-Trent. In Susannah’s absence, I have temporarily returned to a bachelor’s life, doing my own cooking again, which has been fun. [Susannah: To be clear, he is a wonderful cook, and would cook for us all the time if I let him, but I am still enjoying myself cooking for both of us too much to let him do so frequently. I’m sure I’ll get over this at some point.] I had been expecting that some acquaintances would be staying for much of the week after my return, but they ended up changing their plans, so things were quieter than I had expected.

On the Saturday after my return, I made a trip into Hanley, the main town of the Potteries. Stoke-on-Trent generally suffers from extreme economic decline, and Hanley is definitely one of the parts of the city where this decline is more visible. Bethesda Chapel, a former Methodist, once known as the ‘Cathedral of the Potteries’, had an open day in the morning and, as I had never seen inside the building, I wanted to take advantage of the opportunity.

Bethesda Chapel once seated around 2,500 worshipers but, with dwindling numbers and rising maintenance and repair costs, the Chapel closed in 1985. More recently, there have been attempts to restore the building, or at least to arrest its deterioration.

Unfortunately, the building’s prospects are limited due to its lack of a suitable car park. Many of the worshipers at the chapel would formerly have walked from nearby terraced housing, but most of the local housing no longer exists, churchgoing has radically declined from the highwater mark that such a building represents, and, as there are two large theatres in short walking distance of it, it would be difficult for it to operate effectively as another such location. Talking with one of the volunteers in the chapel, I discovered that key decisions about the future of the building were being made, but its fate was still unclear.

Looking around Hanley, one sees occasional indicators of what the Potteries used to be, but recent years have witnessed a marked decline in the town’s appearance and fortunes. There is almost a palpable depression hanging over the place. However, talking with volunteers in the chapel and with my Uber driver on the ride home, I was encouraged by the fact that many people, like me, still care about the place, and are doing what they can to preserve and restore its treasures.

The next weekend, I travelled up to Stockport, where I spoke at a conference on the Saturday. I delivered three talks of around fifty minutes each on the theology of the body. After the afternoon was over, I had a meal with one of the pastors of the church and his family, before going to my accommodation for the evening. Stockport is less than half an hour from Stoke, and it was a blessing to see what the church there is doing, and to have encouraging conversations with a number of Christians there. One of the buildings where the church there meets is in an old mill, which naturally appealed to my love of industrial heritage!

The next day I delivered two sermons (the audio of one of which is linked below). Between the two, I had a wonderful meal with a couple, a pastor of the church, who had invited me, and his wife, whom I first knew as the daughter of one of the elders of the church I had attended since I was sixteen. After the second service, I caught the train back to Stoke.

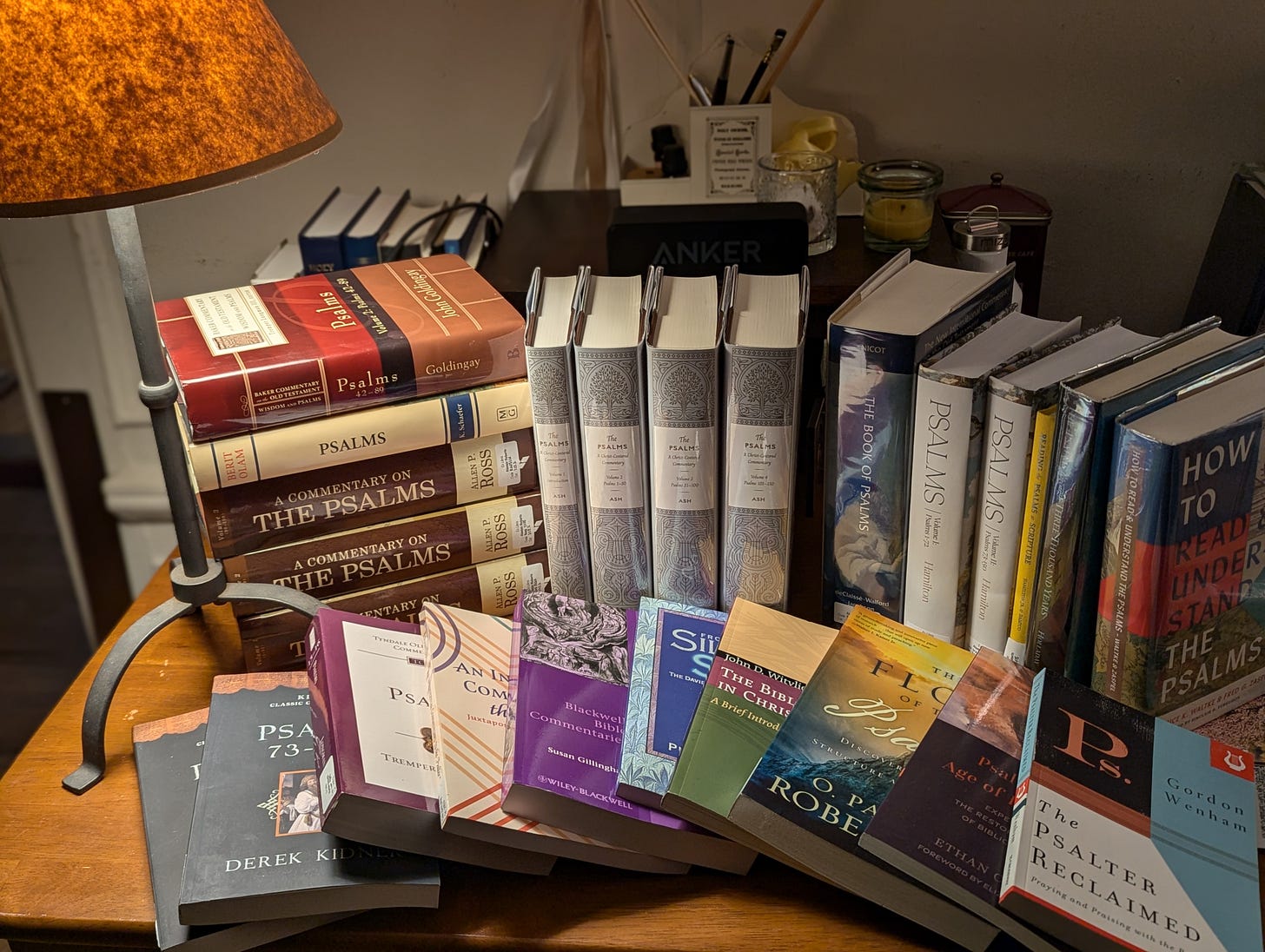

The week that followed was another very busy one, during which Stoke also experienced its first snow of the winter. Among many other things, I have been planning my next Davenant course, on the subject of the Psalms. I am increasingly excited by the prospect of teaching that course, which will be a wide-ranging treatment of the book and contents. If you are interested in taking the course, it is now open for registration!

On top of my work, I was dashing to finish knitting a blanket for my father, which I wanted to give to him before I left for the US. It was my fourth such creation in about a year and a half. In the early hours of Saturday evening, I finally completed it. After church on Sunday, I joined my parents for a meal in their apartment, where I gave it to him. Although I was very sad to be parted from them for another few months, I was once again reminded of God’s goodness in enabling me to spend so much time with them in this season of their lives. We were also able to pray for a while together before I left.

I am currently writing this while on a Virgin Atlantic flight from Manchester to New York. By the time this is posted, I will be back with Susannah, looking forward to another Christmas in the US. The busyness of the last fortnight will only increase as we move into December.

Saturday, 30th November: I arrived back into New York on Monday evening. The week since then has been very full, mostly with work. I have been writing, recording, preparing for my upcoming Davenant course, and sorting out things in my new office space.

We celebrated Thanksgiving with Susannah’s father and stepmother and a friend, eating a wonderful meal in the Players Club. After that we met up with Susannah’s stepmother’s sister and her family. It has been wonderful to be back with Susannah again, after so long apart. The last few weeks have been significant ones for her, and she will be sharing her news in another post soon.

Retrieval Done Poorly

The Reformed theological ‘retrieval’ movement has been the subject of several important debates recently.

Commenting upon the recent goldrush upon old Reformed political and ethical works, Ryan Hurd registered some of the concerns people have about poor editions, editors, and sloppy AI-assisted translation work, but went on to say

most concerning is that these works, already carefully curated and excised out of a very large and complex tradition—and thus inherently inclined to misappropriation—will not be read so as to actually apprehend whatever these texts are saying, but will rather be misread out of context (inter alia) and usurped so as to support whatever current political fads are now in fashion.

The Protestant tradition does not have a texts problem; it has a reading problem.

There are a multitude of great texts that are out of print, in archaic English, or in some other language. It has been a privilege to work for an organization such as the Davenant Institute, committed to the retrieval of such works—identifying, translating or modernizing, publishing, and teaching them. So much of our theological heritage is inaccessible or forgotten and it is encouraging to work alongside many who are doing sterling work to open it up.

While these works were in Latin, some foreign language, older English, or out of print, there was a natural barrier to accessing them. To discover or access them, you would typically need to be proficient in and to read them in Latin. The Latin would slow readers down and encourage more careful reading. To develop proficiency in the language and with terminology more specific to the genre of text, one would also typically have developed familiarity with several other comparable works, and would be better able to read them on their own terms. Outside of a more academic context of engagement and a more scholarly readership, such works would be largely inaccessible. This relatively high bar for access generally restricted the texts to skilled readers, who would ideally be held accountable by similarly skilled peers. Likewise, the fact that one could only discover many of the works through extensive familiarity with a broader body of primary and secondary literature, chasing down footnotes, scouring shelves, reading specialist journals, and locating rare copies of old texts, meant that, by the time that a book came into your hands, you were likely to have a good sense of its place within the broader corpus.

It is encouraging to see many of these works being made accessible to wider audiences. However, Ryan is right to draw attention to some of the attendant dangers and trade-offs of increased accessibility. Scholars are by no means all careful or good readers and many lay people are, yet, with a high bar of entry and with shared disciplines of, some degree of accountability to peers, and exposure to critics in their reading there are both selection effects and controls that tip the balances more in favour of careful reading.

Retrieval will always be curation, whether it acknowledges itself to be so or not, and this is one of the criteria by which it must be assessed. When works are made readily accessible to people apart from scholarly familiarity with their place in a wider corpus, they are much more vulnerable to misappropriation. This problem is compounded when the appropriation of the texts of a tradition is subject to narrow or partisan contemporary preoccupations and published for audiences with little sense of the principles by which texts were selected for retrieval and a wider history of their reception.

For instance, many have commented upon the way that the retrieval of Puritan theology in the second half of the twentieth century tended to excise much of the political and sociological material of the corpus and the retrieved sources. While the works that were recovered were of great value, and the criteria of such retrieval projects were not entirely unreasonable (material of spiritual counsel and theology having a more perennial character), where readers were unaware of material that was being neglected or excised in the retrieval projects, a distorted impression of the Puritans and their concerns could easily arise. Recovery of some of their political and sociological works can consequently be a helpful corrective.

However, here Ryan’s concern about ‘current political fads’ is important to register. The politicization of retrieval is a dangerous thing, conducive to careless reading and motivated misreading. When texts are appropriated for political ends, their reading can easily be resituated, outside of the world of skilled readers of differing and cross-examining perspectives in the academy and into more tribal and activist contexts where usefulness becomes the chief criterion of their reading and appropriation.

More recently, some engaged in retrieval of political and sociological works for popular audiences have attacked a principle of curation. The purpose of retrieval, they argue, is to publish all the texts in accessible forms and let the chips fall where they may. Of course, retrieval is an activity that is labour-intensive, expensive, and demanding considerable time and skill. Decisions must be made about which texts to prioritize, and those decisions are reasonably subject to some scrutiny.

As an extreme instance—important even if not representative—Sacra Press, a small new publisher, is publishing Cajus Fabricius’s work of Nazi apologism, Positive Christianity in the Third Reich (it seems that Fabricius later changed his mind about the Nazis). Now, such a work (which is available for free online) might be of interest to a historian, although its place within the Christian tradition is purely one of deep shame, if it belongs at all. At a stretch, one could perhaps imagine a large scholarly press publishing it along with other works of Nazi propaganda, in an edition designed for researchers of the period. However, Sacra Press is a tiny outfit, with only ten titles, with a self-declared mission ‘to renew the Christian West by publishing the sacred truth for a new day.’ Fabricius’s work is offered on a page with the tagline: ‘Welcome to the Armory. Select your weapons and join the fight.’ Publishing such a book raises comparable questions to those that would be raised by a small Christian publisher republishing an old scholarly text arguing against the resurrection; whatever the scholarly significance of the text, the choice of such a publisher to publish it raises serious questions about the character of its mission and the historical works to which it wants readers to give their attention.

Retrieval cannot be a neutral enterprise. The criteria by which some engaged in retrieval select and prioritize texts may be poor, but everyone will be operating with some criteria. No one is simply engaged in a neutral recovery of some entire corpus (not least because the boundaries of the corpus of any tradition will be contestable). Nor are those engaged in such retrieval usually persons with a liberal commitment to maximal free speech and radical confidence in the invisible hand of the public square to sort out truth from error. They usually believe that certain books should be restricted in their circulation and kept out of the hands of wider audiences. Choices are being made, and those choices should be acknowledged.

Some have also recently even presented their work of retrieval as a rebellion against the current corrupt ‘gatekeepers’ and scholarly curators of the tradition. They are, they maintain, simply returning the tradition to the masses, its rightful owners. Seeking to discredit the current acting custodians of the tradition, they hubristically cast themselves as their replacement, while dissembling their own forms of mediation. Far from the benevolent act they present it to be, they are undertaking a revolution in which a broader scholarly guild is replaced by their tribal clique, who hope to become sole curators of the tradition. It is important to bring the tradition to a wider audience, but full responsibility and accountability should be taken for the work of curation that will never cease to be both required and exercised. Texts must be selected, their place in a wider corpus communicated, their contents taught, skills of reading inculcated, and practices and disciplines of reading established. Where people are not acknowledging the necessity of these tasks and reckoning with the contestability of their proper performance, they are likely either abdicating crucial tasks or dissembling a power move. Supposedly throwing open the gates to unregulated information and inviting people to do their own research, as has occurred in the Internet Age, does not create a sane and well-informed public, but paranoid and confused sheep without shepherds, led this way and that by unreliable persons and groups who put themselves forward as faithful guides, while discrediting most others.

While there is likely a greater alignment of the horizons and concerns of writer and reader when it comes to spiritual or theological works, the social and political lineaments and concerns of our world are vastly different from those of the past, so conversations between the two, while valuable, are a much trickier business. In the appropriation of such sociological and political texts, there is a greater danger of ventriloquizing our contemporary preoccupations into the tradition. This is one of the concerns raised by John Ehrett’s article ‘The End of Protestant Retrieval’, another text that sparked the recent discussions. Within his article, Ehrett considers attempts to ‘retrieve’ the Reformers’ political and sociological thought four or five centuries later. The contextual deliberations of political theologians in the Reformed tradition, while informed in many respects by perennial principles and involving jurisprudential reasoning from which we might learn much, can certainly not be readily ‘ported’ into modern society. In this regard, it must be distinguished from their properly theological thought, whose relevance more clearly persists.

We might perhaps compare such material to the case law of Scripture, which addresses a society radically different from our own. The case law is inspired scripture and must be closely considered as such (as we have been doing in our ongoing podcast series on the book of Deuteronomy—now around sixty hours in length!). However, it does not function in the same way as the Ten Words of the covenant. Attempts simply to ‘port’ old covenant case law to modern society (such as those exemplified by the theonomic reconstructionist movement) are typically misguided, even if we should be studying and learning from such case law.

Especially in the movement commonly known as ‘Christian Nationalism’, there have been attempts to recover aspects of political and sociological thought from the Reformed tradition and to apply them more directly to contemporary polities and societies. As this thought is seen to represent ‘the tradition’, it is presumed to have an authority that, if not dispositive of contemporary sociological and political questions, clearly ought to weigh heavily in our deliberations.

Seldom is sufficient attention given to just how radically our world differs from that of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and the ill-fittingness of many political categories chiefly designed for such a world to our own. As I have put it in the past:

The years from 1650 to 1950… involved a series of interconnected vast and disjunctive social transformations in the West, including, among many other things, the Scientific Revolution, the rise of capitalism, the Age of Imperialism, the Enlightenment, the Age of Revolution, the Industrial Revolution, the rise of the market society, electrification, near universal literacy, antibiotics and other transformative developments in healthcare, mass urbanization, railways, automobiles, and planes, the invention of the telegraph and the phone, of the steam printing press, the radio, and the television, two world wars, and innumerable ideological and political developments in large measure catalyzed and precipitated by these upheavals.

Especially in an American context, for instance, when we talk about the ‘nation’, there is a vast divide between what we are referring to and the sorts of polities considered in the writings of seventeenth century theorists. Again, this certainly does not mean that we have nothing to learn from reflecting upon their works, but we must not be naïve about the dangers of simplistic applications of their political and sociological considerations to our radically different world.

Much of what is needed here are the sorts of historical, empirical, and scholarly sensibilities that make us attentive to the contingency and particularity of our social, cultural, and political contexts and patient and attentive in our handling of texts from very different worlds. Current attempts at the retrieval of political thought tend to be overly rationalist, often operating chiefly at the level of abstract words, categories, and logic, and, overidentifying words with things, obfuscating the complex lineaments of the actual realities of which they are supposed to speak. It is all very well to have an elaborate theory of ‘nationhood’, for instance, but where historical and empirical considerations of the specific character of a polity or people are lacking, this may prove little more than a Procrustean bed. The sorts of real-world entities to which terms like ‘nation’ get attached in contemporary discourse are profoundly different from those of the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries.

And, in contrast to more ideological political projects, careful stock must be taken of our historical and social contexts when considering political proposals. As Rowan Williams comments on the work of Richard Hooker (see my discussion of Hooker here):

But what Hooker’s thesis also reminds us of in a contemporary context is the perennial seductiveness of a radical program uninterested in what has made us the subjects we now are. Changing polities is a futile exercise if we are not prepared to come to terms with the history that conditions and limits us, that gives us the very language in which to pose political questions. Ignore this, and you end up with the modern version of primitivist positivism (we can both discover and return to an age before the distortions of dualist/patriarchal/exploitative consciousness) or timeless rationalism (the principles of liberal secularist democracy are obvious, and the dissenter—the Muslim, for instance—is not really a partner in reasonable conversation). Hooker at least obliges us to think about how we came to pose our questions like this, and how, therefore, our questions and aspirations are continuous with those of our history. To ask, for instance, why monarchy ever looked like a compelling model of how to direct human beings to a goal of happiness may be of more political use than a bald dismissal of it. If we are able to “talk” with our history, assuming some common human ground about ultimate goods being sought, we should be able to see how history is both ourselves and other—rather this than that attitude which, by assuming the obvious reasonableness of where we are now and how we talk now, simply sees history as an unsuccessful approximation to the triumphant “sameness” of modernity (and so also sees the non-standardly-modern aspects of the present world as primitive or retarded). Hooker does at least insist that what we are is made, that we cannot reconstruct “original positions,” and that whatever political futures we desire have to be reworkings of what historical limitation has constructed for us, even if—as we hope—they can be more than repetitions.

Much of the value of ‘retrieval’ is found in the way that it can equip us for such ‘talking with our history’. It pushes against our presentism, against the many ways in which our immediate contexts set our priorities, establish our agendas, direct our attention, frame our questions, and drive us by its urgency. The real value of the political and sociological thought of past ages is more often than not found less in its usefulness as ammunition for pressing contemporary disputes as for it alerting us to the historical contingency of our concerns and questions. This requires a degree of suspension of our preoccupations and, while fruitful conversation can and should occur between our social concerns and questions and those of past ages, good historical instincts help to ensure that both poles of such a conversation enjoy their proper integrity.

This is one of the reasons why the subjection of the work of retrieval to presentist political preoccupations and projects should be a cause of dismay. Such a subjection undermines good reading: we will end up listening for things that are useful to us in texts, rather than listening to them and opening ourselves up to new vantage points from the encounter (while we must make choices about which texts to prioritize, good criteria will typically variously relate to their aptness for encouraging true conversation, e.g. leading voices in the history or texts that are particularly stimulating of insight). The Church and the academy need to be resistant to co-option by political causes for this reason.

The focus of my own vocation is largely on the reading of Holy Scripture. I have consistently seen how badly a preoccupation with pressing social and political concerns will distort and constrain people’s reading of it. We must attend to the Scriptures (and the tradition) on their own terms if we truly want their insights. Those insights have much to say to our social and political concerns, but we will only truly open ourselves up to them when we are prepared to suspend our own agendas.

Both the church and the academy serve good reading by resisting the urgency of the current political moment, making the space and the time for disciplined reflection upon realities, texts, and principles that don’t exist to serve our social and political interests and causes. Out of such disciplined reflection, one will repeatedly find new light is shed upon contemporary issues, enabling us to see them from an angle we had not formerly done. This happens most effectively when we are not approaching texts for their usefulness to our political agendas.

The task of retrieval is immensely worthwhile. However, where texts are selected according to their serviceability for narrow contemporary ends, we lose much of its value.

‘Infohazards’ and the Danger of Knowledge without Formation

The following thoughts arose from considerations independent of the above discussion of retrieval. They should not be read as a straightforward commentary upon the retrieval debate, although they clearly are not without some relevance to it.

The concept of the ‘infohazard’ has entered popular online parlance, referring to knowledge that is dangerous to know. The ‘danger’ in view can be of varying kinds, and those to whom the knowledge poses a danger can differ. For instance, we might consider the danger posed to society if knowledge of how one could create effective chemical weapons from common kitchen products were spread. Examples of ‘infohazards’ could be multiplied if we focused upon knowledge that we keep from children for their own safety, good, and the good of those around them. We probably all remember the frustration of being told as children that we were not old enough to be told something or to be exposed to certain media, yet, in retrospect, we probably recognize that in many cases, these restrictions were for our wellbeing and we are thankful that they existed.

To my mind, the most interesting (and illuminating) deployment of this concept has been in reference to forms of knowledge that increase the likelihood people will cause some form of harm to themselves or be psychologically or morally damaged by the knowledge itself.

A drug addict finding out or being told where they can obtain substances that they will be tempted to use to their own harm is an example of potentially destructive knowledge. Another would be true information that might tempt someone to despair. ‘Trigger warnings’, while greatly misused, do have reasonable application in situations where matters are being discussed that might cause a person distress for which they are unprepared; these are often instances of, or closely related to, ‘infohazards’.

There are situations where we might look more closely at some context and discover an unsettling hidden truth. Having done so we might ‘know too much’ and find ourselves faced with moral quandaries and duties those who never look too closely will not. For instance, you might accidentally overhear a private conversation, investigate matters more, and discover that your boss is engaging in criminal activity. It may be good that the hidden truth of your boss’s criminal activity comes to light, but coming to know it will make your life considerably more unpleasant and complex, even bracketing the external threats you might face for knowing it. You will face choices, for instance, between a now complicit silence or following your sense of duty to blow the whistle, which could likely lead to loss of your job and many friendships.

There are also ‘infohazards’ that involve exposing people to facts or ideas they are unprepared for, which can cause them moral harm. Often this is a particular danger for the young and immature, for people with a limited sense of contextualizing truths, or weak morals. Likewise, some people, sometimes on account of mental illness or disorder, are particularly susceptible to developing destructive and obsessive preoccupations. Care must be taken when exposing them to certain ideas and facts.

An example here might be things that feed destructive paranoia and distrust in people, whether ideologies of suspicion or rumours about what their friends and acquaintances are saying behind their back. ‘Knowledge’ of such a kind can destroy marriages, friendships, communities, and polities, not least because they invite and/or cultivate certain broader ways of perceiving the world, practices of suspicion and distrust that are not easily overcome, but which constantly pursue and find further facts with which to confirm themselves.

Whether in its discussion of wisdom, or various forms of sin and folly, Scripture is alert to how approaches to knowledge can feed and strengthen either virtues or vices. The beginning of wisdom is the fear of the Lord, principally a posture of heart, and the disorder of those who reject this will not be remedied by the accumulation of further ‘knowledge’. As Paul recognizes in 1 Corinthians 8:1-2, the wrong form of ‘knowledge’ can puff up in pride, can lead people to cause spiritual harm to others, or carelessly to dabble in things that might cause spiritual harm to themselves. In other cases, it is the vice of lust that produces prurient interest. In others, ‘knowledge’ is less about serving the vice of pride or lust than that of wrath. There are those whose quest for ‘knowledge’ is driven by the vice of wrath, by a love of contention and rivalrous desires for power and wealth. Paul describes such a kind of person in 1 Timothy 6:4-5—

He has an unhealthy craving for controversy and for quarrels about words, which produce envy, dissension, slander, evil suspicions, and constant friction among people who are depraved in mind and deprived of the truth, imagining that godliness is a means of gain.

The danger of infohazards can be compounded for the curious, who are attracted to that which is dangerous, transgressive, forbidden, off limits, or difficult to access.

For some, the danger is that knowledge of certain (even true) facts will lead them to hate or despise their neighbour, causing moral harm to themselves, and risking them causing various forms of harm to their neighbour. There are many young men, for instance, who have fallen into misogyny in such a manner. Some psychological wound that they have suffered—perhaps a romantic rejection—may have become infected with bitterness and now they are preoccupied with voices, ideas, and facts that confirm them in the animus they have against women. There is no shortage of instances of injustice against men at the hands of women or examples of vicious and sinful behaviour by women, and men who have been infected by the bitterness of misogyny will constantly feed it with them. There are also so-called ‘hatefacts’, politically incorrect or incendiary facts, or facts that fuel hatred of some other group.

Christian pastors and spiritual instructors should be aware of the serious threat that certain facts, ideas, and teachings can pose to the faith and spiritual health of people who are not prepared for them, even though those facts, ideas, or teachings might be quite familiar and unthreatening to many. A lot of theology, for instance, deals with issues that might badly unsettle the sincere faith of young or simple Christians. Ideally, many should reach a point where they are mature and knowledgeable enough to tackle such matters, but it is irresponsible carelessly or recklessly to expose people to things that will harm them because they are not sufficiently prepared.

There is a sort of uncritical valorization of knowledge and its dissemination in many circles, especially online with its democratic and anti-elite commitments. The mere fact that the Internet makes it incredibly difficult to limit people’s access to dangerous and unfiltered ‘knowledge’ can be treated as if it were a natural fact of the universe, with any resisting it being hopeless and retrograde obscurantists. While we might face losing battles on such issues and perhaps appear weird and backward in fighting them, the profound disorder of what has come to be regarded as ‘normal’ must be registered.

We should recognize that the Internet produces a Wild West environment, within which the quest for ‘knowledge’ more often than not proceeds untamed by any formation in virtue that once mediated the deposit of tradition. This is perhaps a fact of life. It is also a deep disorder.

As it is a near fact of life, we must carefully and prudently operate in such a disordered environment, rather than merely lamenting it. Yet to perceive it truly, we must also lament it.

Such a posture is often mischaracterized as elites and scholars wanting to control and hold down the masses. Rather, the issue is that formation in virtue is key in education; when pursuit of knowledge is merely feral, vicious, or driven by mere curiosity, people are deprived of education and will almost invariably be malformed as a result. The Internet undermines the ‘distemporariness’ of the teacher and the learner and the processes by which the good teacher guides their students into a form of knowledge that is good for their souls. It throws information at people and robs them of mature guides. Indeed, the Internet specializes in the spreading of ‘knowledge’ designed to subvert and discredit authorities, with little concern to establish good authorities in place of bad. Much ‘conspiracy theorizing’ comes with such dangers.

Not all forms of knowledge are good. And there are certainly ‘unsafe’ forms of knowledge. This does not mean that such knowledge should be completely off-limits, but treatment of it needs to be careful and restricted to people who will handle it responsibly and with awareness of and alertness to the dangers that comes with careless treatment.

Christian teachers especially should recognize education as moral formation and be very alert to the dangers of ‘information’ detached from guidance into virtue, or of uncritical celebration of ‘knowledge’ as such. As the reality of ‘infohazards’ alerts us to, truth isn’t ‘safe’; we are operating with live ammunition and eternal souls. We must speak and act accordingly.

Voting and Virtue

In our previous post, I shared a few thoughts challenging understandings of voting that focus narrowly upon moral approbation of parties, candidates, and platforms. Here, I want to consider another dimension of the meaning of voting, hopefully with the added advantage of not implying any specific political subtext.

My best argument for having a minimal baseline for candidate quality (and refusing to vote lesser-of-evils when it isn’t met) is that the ability of your vote to change the outcome of an election is much (so very much!) smaller than its ability to change your own mind and heart. Don’t yoke yourself to any person or cause that will constantly tempt you into compromising your own beliefs or defending evil, purely for the sake of winning a short-term victory.

“Where your treasure is, there will your heart be also.”

I should state clearly at the outset that I really do not think such an argument should generally be dispositive for the question of whether or not (and for whom) we vote. Faced with the moral questions and fierce ethical arguments surrounding voting, it is easy to feel that, whichever way we vote or not, we are complicit in evil somehow. At such times, we can remember that, as sinners in a fallen world, this is a fact of our lives. We should seek to serve God and love our neighbours. We should keep the politics of this age in its proper place. We should not put our trust in any princes or parties. We should consider the options carefully and then vote or not vote prudently. And then we should sleep the sleep of the justified.

However, I think Edward’s claim in his short thread about the possible power of a vote is correct and should be very seriously weighed. I also think considering Edward’s point helps to highlight some of the key differences between the way that pastors and the way that people who are more directly concerned with politics and its study can approach questions of the morality of voting and why both ought to be heeded.

Edward considers the act of voting more from a sort of virtue ethics perspective. Your vote gives a stake in a candidate or party and from this stake one can find oneself drawn into a tribe, invested in persons of dubious character, committed to arguing for lesser(?) evils, etc.

The act of voting, for this approach, is not viewed in a vacuum, but in terms of its typical place in a larger series of actions, associations, and attachments, and the ways that these can serve as processes of formation.

I do not think it should be hard to recognize the measure of truth here. Politics can be one of the most powerful formative realities upon people. It is not difficult to recognize that, for all people might talk about ‘lesser evils’, too few actually handle such with the moral seriousness and care befitting ‘evils’. And, if we are in some way invested in them, those evils, unless we are very careful, can steadily shape us.

By contrast with this approach, people who are more focused upon the realm of politics, rather than that of spiritual formation, will be more likely to consider voting in a narrower act-focused way: as a standalone moral dilemma, with little consideration of the character of the agent or the broader framing of the action. For instance, it might be argued as follows: Society has called upon us to choose. This is a necessary process for its governance and will lead to a single result. If you determine not to vote, or to vote for someone who could never win, you are abdicating your role in pursuing the best for your society.

However, what Edward considers that such approaches generally do not, is that a vote seldom stands in isolation as an act. If we are to consider what a vote means, we need to do so within the cluster of realities that typically surround it. For instance, while people may justify their voting by appeal to moral principles and worthy ends, the actual dynamics of voting have a great deal to do with more enduring group affiliation, loyalty, and stake. It is not an isolated moral judgment or act.

We could compare this discussion to the difference between a debate about just war theory and whether acts of lethal force can be justified in the abstract and consideration of war as a formative reality for those engaged in it. The latter, it seems to me, raises tougher issues.

War is a realm of profound moral danger. Wars must be fought and I think Christians can often be justified in fighting in them. However, war often produces calloused consciences. Its imperatives can shut down moral vision and pervert judgment. It is a realm of ‘evils’.

Politics, it seems to me, is not altogether dissimilar. As we engage in it, we put our souls and consciences in a position of jeopardy. It may be necessary to choose between evils in a fallen world—we may even have a moral duty to do so. However, it is a dirty and dangerous business.

There are times when, it seems to me, we must fight. We might also need to choose lesser evils. However, it is essential we are deeply alert to those ‘evils’ and give a full accounting of them. We should not merely discount them when we consider greater evils we sought to avert or avoid.

No light excuses should be accepted here. Responsibility for choosing a lesser evil need not be considered in terms of ‘guilt’, but it is a real responsibility and must be reckoned. We expose ourselves to serious assessment—though not necessarily condemnation—in such acts.

That it can be just and even necessary to fight does not mean that fighting is good or to be desired. As something that involves moral dangers, we should, if possible, seek to avoid it and, if at all possible, to bound the realms—and the times—within which fighting occurs.

Sending women and children to fight wars, for instance, exposes more vulnerable members of society to the formative power of war. Likewise, realms and times of peace and non-combatants need to be set apart from war. King David, as a man of blood, could not build the temple.

Too many people approach things like just war permissively, as if the fact that it might be moral to fight meant that we could engage in it unreservedly. Or that mourning, sorrow, and penitence should not be a necessary accompaniment to those situations where we must shed blood.

Our society, with things such as various extensions of the franchise, the rise of mass media, and, more recently, with radical democratization of the means of publication, has greatly extended the realm and times of, and the participants within, political (ant)agonism. Political conflict has become a persistent and pervasive formative reality in our society, with little lingering awareness of how destructive this can be to virtue and the common good.

Pastors, as persons charged with guarding and discipling souls should be highly alert to this.

I am not opposed to voting in principle and have certainly voted before, even if my preferred and usual practice is not to vote. Voting is necessary for society, but knowing my vote will not have an effect is a mercy for which I have often been grateful.

In response to a Kantian logic of universalizable moral imperatives, I treat this as similar to a situation where a nation needs to go to war, yet should ideally keep those it sends to war to a minimum. If you are not needed or would make no difference, you probably should not volunteer.

Of course, there are numerous ways to be politically involved that do not entail choices between evils. You could write to representatives, campaign for policy changes, support worthy causes, etc. You could also seek to push back against the totalization of political antagonism.

I have written before about the sobering experience of realizing what investment in political antagonism did to my soul. The last few years, it has also been sad to see its effects upon many in movements such as Christian Nationalism.

I think politics is very important and that Christians can—and in many cases should—actively and righteously participate in it. Caring about politics is not sinful or idolatrous. However, politics is an inherently dangerous realm of activity and we must watch our souls. If Christians are to do politics, they need to do so in a manner alert to its moral dangers. Pastors really are needed here. Without delegitimating the necessary work and choices politics requires, they can be rare voices in the wilderness of societies that are given over to it.

Politics and the Willingness to ‘Die’

I have been thinking a lot about the potential spiritual dangers of (often necessary) political investment of late. One of the key questions that we need to ask ourselves when choosing between evils—as we sometimes must—is at what point we are prepared to ‘die’.

‘Dying’ might be a matter of losing our livelihood, our reputation, our friends, or our place at the table. It might be a matter of our side losing. It might be submitting to persecution. It might be our institution collapsing. It might be the surrendering of our legacy.

Faced with the possibility of ‘death’, most people recoil and will choose some other ‘evil’. It is such a fear of ‘death’, for instance, that helps people rationalize covering up or allowing abuse: they feel that too much is at stake to risk confronting it. When faced with the ‘evil’ of turning the other way as some seemingly unimportant people are abused by a leader and the ‘evil’ of your institution and movement imploding, losing your job, and many of your friends rejecting you if you expose it, the former feels existentially ‘lesser’ to many.

In politics or war, the elevation of expediency and the imperative of victory over principle can be heightened by the sense of justice having been suspended on all sides to some degree, by the greatness of the stakes, and by the pressing urgency of action.

Willingness to countenance ‘death’ rather than committing certain ‘evils’ is key to Christian faith, integral to the meaning of martyrdom. We ought not shrink from a righteous ‘death’ for love of our lives (Revelation 12:11), preferring to lose the whole world over our souls. Jesus teaches us not to resist by evil means (Matthew 5:39). And this entails willingness to suffer evil without retaliation. As Paul asks the Corinthians about such situations, ‘Why not rather suffer wrong? Why not rather be defrauded?’ (1 Corinthians 6:7).

Christian willingness to suffer great harm rather than sin or give up their souls is not something that can easily be compartmentalized from the political realm. Indeed, it has often been most powerfully displayed in such a context. Especially when it comes to things like politics, war, or other contexts where the stakes feel existential, the question of those points where we would willingly suffer ‘death’ rather than take certain actions is a critical one.

People who are unwilling to ‘die’ are liable to lose sight of principles, unprepared to suffer harm for what is right. Ends justify the means and, while they might minimize them when they can, they will countenance all sorts of evils when the stakes feel high enough. Such people will also typically lack moral courage. They have too much of a fear of ‘death’, so will not do what is right when it might really cost them, or at those points when it might really hurt (the ‘death’ in question is not generally of the kind that will win earthly honour).

Our preparedness to suffer ‘death’ is a great test of Christian faith, because we believe in the God who raises the dead, who vindicates martyrs.

This said, we do not rush to martyrdom. We resist righteously where we can. We are shrewd. However, these have their limits. I think that Christians can—and should—be actively involved in some wars and political conflict. The sort of masochism that weakly welcomes ‘persecution’ without any resistance is shameful, but an important part of our political witness remains our willingness to suffer harm.

Further, some of the most courageous and renowned Christian acts of witness have involved a laying down of weapons or refusal to use unjust political means. For instance, St Boniface telling his companions to lay down their arms and not use lethal force to protect their lives. We do not need to be principled pacifists, to deny any legitimacy to self-defence, or to forego political action, to recognize that such acts of witness raise our eyes to something higher and more enduring than any earthly stakes, and perhaps also give us pause in our own actions.

There are greater stakes. There is a higher kingdom. There is a more enduring people. None of these things mean that our earthly struggles or politics do not matter, or are never to be fought for! But we should be prepared to lose and to die under certain circumstances. And therein lies a liberating power for faithful and principled action.

As Luther put it in his great hymn, ‘A Mighty Fortress’:

Then let them take our lives,

goods, children, husbands, wives,

and carry all away;

theirs is a short-lived day,

ours is the lasting kingdom.

And, as our Lord said,

If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross daily and follow me. For whoever would save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will save it. For what does it profit a man if he gains the whole world and loses or forfeits himself?

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ Mere Fidelity has been quieter of late. Matt, Derek, and I have all been extremely busy. We recorded one episode with Amy Mantravadi, on her new book, Broken Bonds: A Novel of the Reformation: Book 1 of 2. We also had a question-and-answer episode with our Patreon supporters. The big news, which Matt shared at the end of the episode with Amy, is that he is leaving the podcast at the end of the year. Derek and I plan to continue producing the podcast, but will be taking a hiatus at the beginning of 2025, during which time we will establish the form that the podcast will take in the future.

❧ The Theopolis Podcast’s Deuteronomy series has also been quieter, as Peter Leithart has been travelling. We are within sight of the end of the book now, after nearly seventy episodes. Our latest episode is Deuteronomy 33: Moses’ Final Blessing on Israel and Deuteronomy 33: Moses’ Final Blessing on Israel, Part 2.

❧ I recently wrote a lengthy piece for the Theopolis website on Pentecost and the Gift of a New Politics.

O’Donovan noted the way that Jesus’ kingdom mission can appear to many to be ‘apolitical’, as it left the seeming primary threat of the colonial oppressors unaddressed. Behind such an impression there commonly lurk misguided notions of the nature of true political power, typically regarding the essence of power to be coercive force. However, the power of Jesus’ kingdom has a character that radically exceeds this (even if it certainly does not entirely exclude it). The power of Rome, to which the known world was in thrall, was not powerful enough, not ‘political’ enough. Jesus granted his people a power that radically exceeded Rome’s in its affordance of the resources required to ground a community’s life.

❧ The good folks at What Would Jesus Tech? invited me to join them for a wide-ranging discussion on the topic of ‘God’s Preferred Medium’.

❧ My biblical reflections are being translated into French. Translations of 2 John, 3 John, and Jude are now available on YouTube.

❧ The latest episodes in my God’s Story Podcast series on Zechariah have been published. With them we tackled Zechariah 5 and Zechariah 6.

❧ I preached on John 3:22-36. For anyone who wants to listen to someone who argues for short sermons preach for around forty-five minutes, here is your opportunity!

❧ I am asked to blurb books from time to time, but never think to share my blurbs here. One recent book I blurbed was Michael Niebauer’s Four Mountains: Encountering God in the Bible from Eden to Zion:

Niebauer conveys both the unity of the witness of the Bible across its texts, but also draws us up to the higher realities that are its true end. From the bracing mountain-top vantage point to which this book guides its readers, a vast scriptural terrain unfolds in its splendour and beauty.

❧ I recorded a version of my reflection ‘The Anglicanism of C.S. Lewis’, which I first wrote for the Anchored Argosy back in February, and a version of which was later published on Ad Fontes.

❧ I have produced videos of several other reflections from this Substack.

Desacralizing and Evangelizing Politics

Some Lessons from Richard Hooker

Jesus the Bridegroom in John

John 21: A Fitting Epilogue

It’s About Time

Upcoming Events

❧ Alastair will be participating in the next session of Davenant’s ongoing Lilly Grant-funded program working on congregational life in a digital age.

❧ Alastair will be speaking at Hephzibah House on the evening of December 11th.

❧ Alastair’s next Davenant course, ‘The Psalms: A Bible in Miniature’, is now available for registration:

In his introduction to his lectures on the Psalms, Martin Luther described the Psalter as ‘a little Bible’, declaring that ‘in it is comprehended most beautifully and briefly everything that is in the entire Bible.’ For nearly three millennia, the psalms have been at the heart of the worship of the people of God. This course will consider the place of the Psalter within the scriptural canon and the life of the Church and its members. It will equip students to read and, more importantly, to sing with greater understanding and benefit. While deepening students’ appreciation of individual psalms, this course aims to give students a firmer theological grasp upon the role and use of the Psalter as a whole, its ordering to Christ, and the ways that it can transform our relationship to Holy Scripture more generally.

❧ Much of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Alastair and Susannah

Your work has always had the benefit of gatekeeping via wordcount. This is much appreciated, and certainly not a waste with regard to clarity.

When I found your work in uni a decade ago, it was a theological lifeline. Most of the people who have been willing to step into my life as mentors during my youth had or have since rejected God. When I look at the cratering of faith in my generation overall and among my peers specifically, it seems you vastly overestimate the maturity and quantity of the guides already in existence. Not everyone is suited to high level theology, political or otherwise, but word gets around as to whether certain people find it important at all, with the usual cascading effects. As for the American experience, early guides often include youth pastors, a role where immaturity is frequently mistaken as a feature rather than a bug. All in all, no need to be bearish on people trying to understand and apply God's word in the modern context, the Spirit has used lesser motives.

Thank you for your reflections, especially pertaining to retrieval. God bless!