Dear friends,

Susannah: I gave a talk last night at KGB Bar on East 4th Street — a standard friend group hangout owned by a Ukrainian who named it during the Ironic Post-Soviet Period of NYC nightlife and who now rather regrets his choice of name. It’s a great place, and (without realizing that I was going to give a talk there) two friends miscellaneously showed up, along with the co-owner of the bar/building, a friend, who in my first lockdown, in late February 2020, when I was just back from Venice/England/Vienna and in quarantine in an airbnb on the Upper West Side, brought me masks, during a time when we were all completely freaking out and didn’t know how to be at all chill about covid and also there were no masks available in the city.

ANYWAY, it was great to see everyone. The event was Episode 25 of the Dead Ladies Show, a series of public talks that started in Berlin & moved to Manhattan in like 2019. Women (and the occasional man - there was a guy in this batch of talks who spoke on Jessi Combs, who set the car-racing land speed record for women) give talks on women who they think should be better known. Here is my talk! Enjoy. (Spoiler: St. Monica of Thagaste did not set any land-speed records that I know of.)

ALSO:

If instead of (or in addition to) reading about St. Monica, you would like to hear Leah Libresco & me grilling Freddie deBoer about the state of the Left in America, metaethics and the basis on which he believes human beings to have value, see our podcast here!

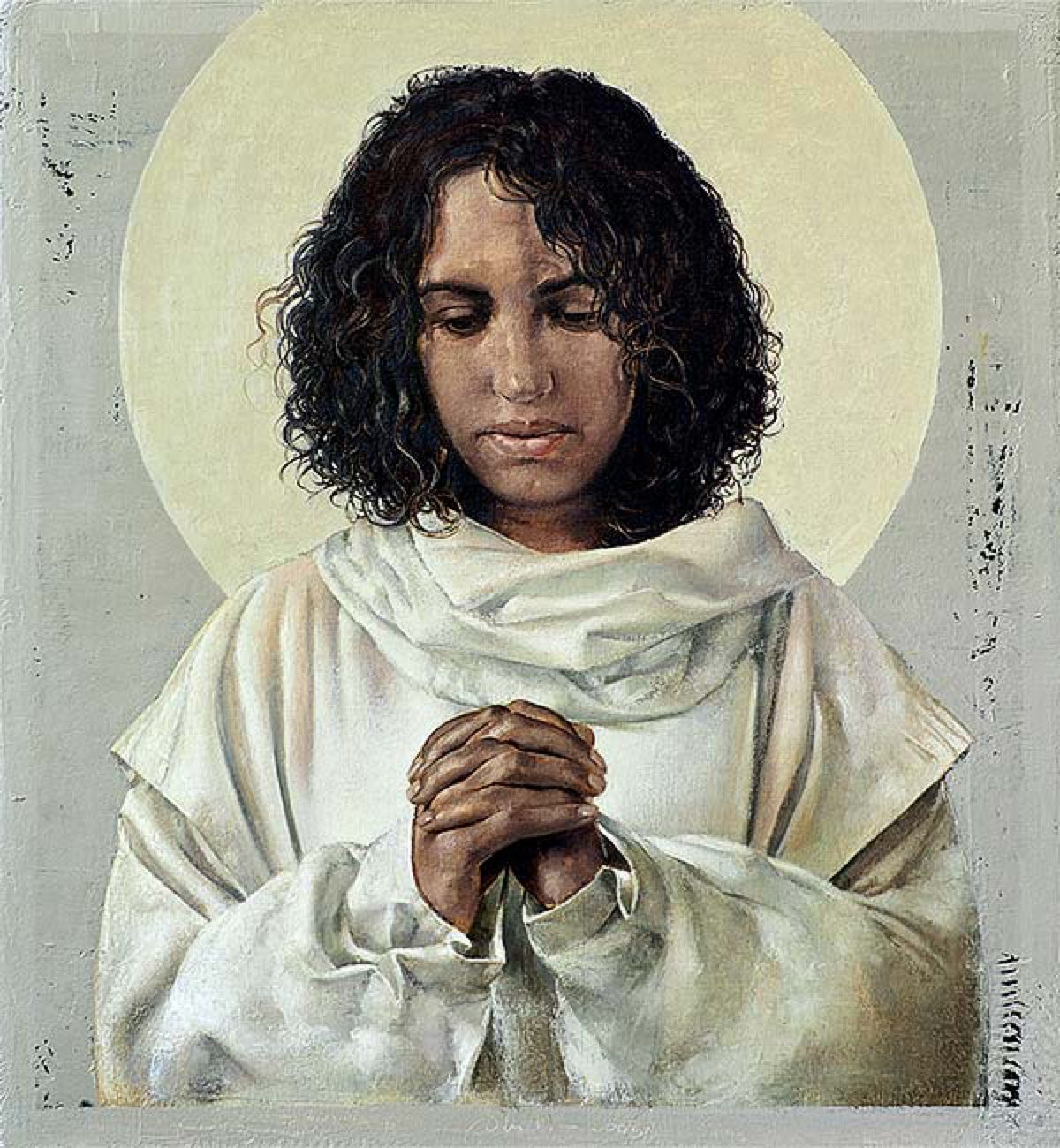

Monica of Thagaste, 330-387 AD

Truly, O LORD, I am Your servant; I am Your servant, the son of Your maidservant; You have loosed my bonds.

Psalm 116:16 (ESV)

Some people’s stories seem to hinge on a single event: their behavior in that one moment, at that one extremity, shows us who they are, however much that heroism has been built by previous habits. Think of Desmond Doss, unarmed, darting out into the open, under sniper fire at Hacksaw Ridge on Okinawa in 1945, to field-treat and haul to safety man after downed man.

The stories of others are not like that. It is their persistence, their patience, their sheer faithfulness in hope over years and years which tells us who they are. Monica, the mother of Augustine of Hippo, is one of these.

Born in Thagaste in what is now Algeria in 332 AD, Monica was an ethnic Berber, whose parents had raised her as a Christian. Her marriage to the Roman pagan Patricius was difficult; he was unfaithful, quick-tempered, and, as his name suggests, very much the Roman patrician, though he could be kind. This marriage, and what it implied, illuminates the world in which it took place.

Monica was born five years before the Emperor Constantine died, nineteen years after he had passed the Edict of Milan which granted Christians, and all others in the Empire, freedom to practice their religion. Two years before she was born, Constantine had moved the capitol of the Empire from Rome to Constantinople - sort of. Administratively. Not imaginatively. Rome was still Rome.

What was Rome? What was this world, this empire? It’s hard for us to picture, because we think in terms of continents: Europe, Africa, Asia. We think of the ocean as something that separates places.

For them, our world, with its land routes and continental, nation-state focus, would have looked inside out. The Mediterranean was their subway system, and the world was all the stops along its coasts, plus places up to around 100 miles inland. Of course there were other places in the world, but nowhere that really mattered. Thagaste was around 45 miles inland from the coast. It was of course in Africa, but no less Roman, no less part of the Empire, than Sicily was, or Crete. An Empire that was, as was apparent to everybody, changing fast. You might even say it was falling, though they would not have said so.

What the legalization of Christianity meant was that someone like Monica, born to Christian parents who had lived through the time of persecution, could practice her faith openly. Her parents could also balance their piety with their ambition, marrying their daughter to a high-born Pagan Roman (though one who was persistently strapped for cash). He was part of the old-fashioned, conservative Pagan establishment, and the difference in vision for marriage and standards of conduct meant that Monica’s marriage was not an easy one.

This culture was profoundly civilized: it had flush toilets, enormous public works, rapid and efficient trade routes, cities packed with apartment buildings, heated bath houses, and a kind of Roman monoculture everywhere: every city in the empire had its amphitheater where gladiators still died for the pleasure of the spectators, and players still played the Greek plays. It was also profoundly brutal, most particularly in its attitudes towards the lower classes, sex and children. The Roman paterfamilias had the power of life or death over his household, and had no real obligation to fidelity to his wife: building up the prominence of the family was his primary job, and that meant that unhealthy or unwanted children could be refused membership in the family. Infanticide was not made illegal until 374. Prostitution was legal, as was slavery.

Every civilization has of course warring visions of the good within it, and pre-Christian Roman civilization did not entirely despise pity or weakness. It only mostly did. In any case, the idea of a servant king, a God who died on a cross like a slave, was still deeply bizarre and offensive to people like Monica’s husband.

All of this was tottering. Two years after infanticide was outlawed, in 376, a large number of barbarians from the Germanies entered Roman territory, and the armies of the Western Empire were gradually worn down; the generation after Augustine would see it become what we would call an entirely failed state, its territories subject to the whims of warlords who would over the next several centuries become Europe’s kings. These kings were strangers to the hyperconnected cosmopolitan pagan culture of the empire - we would find them more alien in some ways than Augustine’s father.

But we would find them in other ways more familiar: it was in their reigns that slavery in Christendom was very gradually abolished, a project only completed a couple of centuries before it was reintroduced in the New World. The abolition of slavery had not even been an ambition for the Roman world, nor had chastity, nor fidelity in marriage, nor the care for each human, however outcast and poor, as one made in the image of a God who himself had been born poor and had been cast out.

The code of chivalry, with its attempt to unite the vision of Christian gentleness and humility and care for the poor with Roman honor and the warrior ethos of the Northern barbarians, was one that the successor civilization to that of Augustine always struggled to live out. But it struggled with the help of the sacraments of the church which Augustine would do so much to help build.

But that was all far in the future. Here, now, in Thagaste, Monica found herself a Roman patrician woman, with deep hopes for her eldest son’s future as an important man, a Roman citizen destined for public life, and a Christian: she did not think these things needed to be in conflict. Augustine the teenager was eventually going to need to be married: he would marry, she decided, eventually. “She was afraid that a wife should prove a clog and hindrance to my prospects,” Augustine explained. “Not those hopes of the world to come, which my mother reposed in You, Lord; but the hope of learning, which both my parents were too desirous I should attain; my father, because he had next to no thought of You, and of me prideful ambitions; my mother, because she accounted that a usual course of study would not only be no hindrance, but even some help towards attaining You. This is at least how I suspect they were thinking, recalling, as well as I can, the dispositions of my parents.

Monica is a very, very familiar type of person. I feel like I know her. Yes, she was Christian. Yes, she wanted Augustine to know Jesus. She also wanted him to be a credit to his family, to get a prestigious degree, to make a name for himself, to get a really good position, to marry later in life and very well and give her lots of patrician-class grandchildren. She was the North African Roman equivalent of an Upper East Side tiger mother and frankly, I can relate.

Augustine was glad enough to leave the house at age 17 to go to Carthage to study rhetoric: it was essentially a pre-law program, though, as with many pre-law students, he never would become a lawyer.

Carthage, 300 BC (600 years before Augustine’s time)

Roman Carthage, c. 300 AD

Carthage Harbor Ruins, contemporary

Monica had the happiness of seeing her husband repent of his screwing around and domestic abuse and be baptized before his death just after Augustine left home: it was an answer to prayer. But her worries were not over. Augustine had, unusually, not been baptized as a child; it seems no one had ever gotten around to it. At school, Augustine, now a long way from his childhood faith, toppled entirely into the kind of respectable debauchery in which many college students find themselves. One thinks of a kind of Late Classical Carthaginian Brideshead Revisited scene, in which the role of, say, Bloomsbury is played by Manichaeism, and the role of the Catholic Church is played by herself.

This part of his life went on for seventeen years. Rather than practice law, he became a teacher of rhetoric, getting posts in Carthage, where the students were hooligans, and Rome, where they tended to not pay their bills. Finally he landed a professorship of rhetoric at Milan, then the premier city in the Western empire. Academic success, intellectual spelunking amidst the most recondite and fashionable of fourth-century Mediterranean heresies, and sexual adventures were extremely attractive. I mentioned Manichaeism: this was Augustine’s philosophy of choice.

Mediolanum/Milan, 4th century AD

“Philosophy” and “religion” were during this time not particularly distinguishable, which had not been the case in say Socrates’ Athens. In the late classical Roman Empire, what you had was a set of competing schools of thought that were also communities and ways of life. Some of them, like Christianity, were at least in theory all-in: you were baptized and then didn’t keep going to the Temple of Jupiter. Some were more pick-and-mix. They also came in varying degrees of nerdiness. I would say that Manichaeism was among the nerdiest of the options. It was newer than Christianity, founded just before Augustine picked it up by the Parthian prophet Mani, and in the form that Augustine knew it presented itself as more intellectual.

It features an elaborate dualistic cosmology: the world is not the creation of a single good God but is instead the site of an epic struggle between a good principle of light and spirit, and a bad principle, which gave rise to both matter and evil. Mani claimed to be teaching the hidden truth behind all other religions: Christianity, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Marcionism, Judaism, Gnosticism, Greek, Roman and Babylonian paganism, and all the popular mystery cults out there. It was making a bid for the position of the Final Boss of religions, with Mani presented as the final prophet after Zoroaster, Moses, the Gautama Buddha, and Jesus.

But Augustine was also interested in Neoplatonism, and in a contrast to the dualistic Manichean cosmos where there is nothing behind the war of equal forces, the vision of the One, of the Good that has no rival, the Good that is completely beautiful and desirable, that is Being itself, haunted him.

The thing about Manicheism, at least as Augustine practiced it, is that you can basically do what you want. Unlike in Christianity, in Manicheism the material world is evil, which means that sex is always evil, even in marriage, so, since there’s not actually an innocent way to live, you might as well not worry that much about it. Augustine certainly didn’t.

Monica did. She worried, and she prayed, and she hassled him. And she cried. And she prayed. And she didn’t give up.

“I cannot sufficiently express the love she had for me,” wrote Augustine years later, “nor how she travailed for me in the spirit with a far keener anguish than when she bore me in the flesh… My mother, your faithful one, wept to you on my behalf more than mothers are accustomed to weep for the bodily deaths of their children. And you heard her her, O Lord…”

Monica wanted to take charge of the situation; she wanted to get Augustine married off to a suitable woman; she wanted some suitable pastor to talk sense into him. God had His own plans. They took a lot longer than she would have wanted. But she did not lose hope.

And she had consolations. At one point, staying in Augustine’s house in Carthage (she tended to follow him around), she had a dream. She was standing on a measuring rod, grieving. A “bright youth” approached her, joyful and smiling, asking her what the matter was. She told him: her son was unsaved, a heretic and living in sin. The youth told her to be at peace, and indicated that she should look, that “where she was there [Augustine] was also.” Sure enough, she looked, and there, in the vision, was Augustine, standing on the same rule.

She told him the dream. “Maybe,” he speculated with deliberate obtuseness, “it means you’re going to become a Manichean.” She put the kibosh on this interpretation. “For it was not told to me that ‘where he is, there you shall be,’ but ‘where you are, there he will be.’” The answer, her certainty, said Augustine later, “moved me more than the dream itself.”

She sought allies, theological debaters who could best her son the intellectual on his own terms. This was St. Augustine: it would have been a tough job. One bishop declined the attempt. “Leave him alone for a while. Only pray God for him. He will of his own accord, by reading, come to discover” the truth.

This was extremely good advice, one feels: Augustine was then at the height of his cage-stage Manichaeism, and would have chewed and spit out a standard bishop like a piece of gristle. But Monica really wanted the debate; she wept as she begged him. He eventually told her to go away, saying however, “As you live, it is impossible that the son of such tears should perish.”

St Augustine Leaving St. Monica and Embarking for Italy, 1465, Benozzo di Lese di Sandro Gozzoli

It was Augustine himself, not Monica, who finally ran into St. Ambrose. He was the bishop of Milan, where Augustine had just moved for his new teaching gig. Augustine had been used to thinking of Christianity as something a little embarrassing, a little boring, and also as something that poked at his conscience. He knew about it already. It was his mother’s religion. He’d been there and had moved on. He was on an intellectual and spiritual quest, and anyway the Latin into which the scriptures had been translated was not as sophisticated as the Latin of his beloved philosophers.

Ambrose knocked him back on his heels. Augustine describes the shoddiness, the flashiness, of the Manichean teachings, as compared to the Christianity that Ambrose taught. This was the real thing: compared to it, Manichaeism seemed like an incoherent and shallow game. He told his mother about this new teacher, and Monica immediately recognized that here was a man who could finally give Augustine a run for his money intellectually, whose mind, whose own curiosity, erudition, and philosophical hunger had been fulfilled in, rather than stifled by, the way of Christ.

Here was a man who could speak to Augustine of the Neoplatonic Good that has no rival who is at the same time the God of the Jews and the Man who died on the cross, and did not stay dead. The Logos of Plotinus and the neoplatonists is the principle of Reason by which all order in the world comes: and it’s him to whom we are introduced in person in the Gospel of John, something of which Plotinus had never dreamed. Christianity itself, shockingly, this religion with its Jewish historical specificity, its stories and its patriarchs and its saints, its mystical-erotic poetry and songs and law codes and court histories and visions, emerges as the goal, the telos, of all philosophy: hidden in plain sight, where he had never thought to look

“You have made us for yourself,” Augustine would write much later, addressing God, “and our hearts are restless until they rest in You.”

St. Augustine, Philip de Champaigne, 1645

Ambrose’s greatness was not merely intellectual: he was a courageous opponent of the abuse of state power, even in these rocky early years of Christianity’s legality. In 390, when Emperor Theodosius gave tacit consent to the massacre of 7000 men in Thessalonica (present day Thessaloniki) by Roman troops in Greece following the lynching of a garrison commander by the people of the town, Ambrose, horrified, excommunicated the emperor, barring him from the Cathedral in his own imperial city of Milan and refusing him communion until he had repented and made some kind of reparations to the citizens.

Ambrose barring Emperor Theodosius from the Cathedral, Anthony van Dyck, 1620

It wasn’t just Ambrose, though. Monica herself was Augustine’s main debating partner. Mother and son carried out what sounds like a persistent argumentative correspondence: they did not stop arguing about theology for seventeen years, and after they began to agree about it, they still didn’t stop talking about it.

St Augustine & St. Monica, Gioacchino Assereto,

Augustine, meanwhile, had embarked on a thirteen year long commonlaw marriage to an unsuitable lower-class woman whom he loved deeply; in 372, in Carthage, she bore him a son. They named the boy Adeodatus, “Given by God;” he was cherished.

Monica was not thrilled. Her son was not going to throw himself away on a woman who was no better than a concubine, who was moreover not a Roman citizen. She refused to approve their marriage, and instead somewhat behind Augustine’s back, arranged his betrothal to a Roman girl of very good, very rich family. The girl was at the time too young, which meant that her plan entailed Augustine waiting another two years or so; in any case he was still in love with Adeodatus’ mother. In obedience to his own mother, he did not marry her, but he didn’t marry the other girl either. He never did marry. He became a celibate priest instead.

Monica’s refusal to accept Adeodatus’ mother as a fitting wife for her son, her refusal to encourage Augustine to make her grandson legitimate, are indications of her own imperfectly crucified pride.

But she did love her grandson as well. She certainly welcomed him into her home; when Augustine and his concubine had, to their mutual agony, parted, the boy had stayed with his father. Her prayers for Augustine and (surely) for Adeodatus were, finally, fulfilled when, on Easter Sunday of 387 AD, they were both baptized into the Christian church. Augustine was 33 years old.

It had been Monica he told first when he had, finally, converted, when the words from Romans like a set of instructions gave him the way of life and the will to walk it. “She was filled with joy,” says Augustine; “You ‘changed her grief into joy’ far more abundantly than she desired, far dearer and more chaste than she expected when she looked for grandchildren begotten of my body.”

I cannot do more than touch on Augustine’s journey here. Monica’s own voyage, once she saw her son and grandson into the safe harbor of the Church, was coming to its end. Over the course of one long night, she and her son had one last long conversation in speculative theology, clambering around in the high and shining realities of Catholic metaphysics as they were, in that dawn and still wet with dew, first being worked out: as the astonishing implications of the Good becoming a baby in Mary’s womb, of Reason learning to speak at her knee, were being drawn. Standing together at the window of their rented house in Ostia, Rome’s harbor city, looking out into the garden, as the new day dawned, they were “searching together in the presence of the truth which is Yourself.”

Ruins of a Private House, Ostia Antica

She came down with a fever five days later, and soon knew that she was dying. She had wanted to be buried with her husband back in Thagaste, but told Augustine not to bother with that - “Nothing is distant from God, and there is no ground for fear that at the last day He will not acknowledge me and raise me up.” She died nine days after the beginning of her illness, in 387, at the age of 56.

Augustine was clearsighted about her; he did not think she was perfect; he, above all others, knew that her love for him, her fidelity in prayer, her hope and trust of God, had had their origins in God’s own love, in his grace. “In her unceasing prayer,” he said, “she as it were presented to you your bond of promises. For your mercy is forever, and you deign to make yourself the debtor obliged by your promises to those to whom you forgive all debts.”

We know Monica almost entirely through the eyes of her son: her story is interwoven throughout his Confessions. She comes through as herself - the faithful, loving, stubborn, somewhat prideful Christian North African/Roman matriarch; pious, philosophically adventurous herself, ambitious, and loving.

She also is cast as many others; she partakes in their natures too - and who’s to say that Augustine was wrong in so casting her?

She was the Widow of Nain, seeking from Jesus the life of her dead son. She was Dido, from whom Aeneis fled from Carthage to Rome. Perhaps above all, she was the Persistent Widow of Jesus’ parable about the value of doggedness in prayer: the one of whom the unjust judge said, “Though I neither fear God nor have regard for people, yet because this widow keeps on bothering me, I will give her justice, or in the end she will wear me out by her unending pleas.’”

She is, after Augustine himself, and God, the main character of his Confessions.

But we have one other testimony to her.

In the summer of 1945, two boys were digging a hole to plant a post for a soccer goal in the courtyard outside the church in Santa Aurea in Ostia. Their shovel hit a stone. On that stone was an inscription. It was Monica’s funerary marker, with her epitaph.

Her body had been long since moved to the city of Rome proper, to the Basilica dedicated to her son. The text had been known because it had been recorded at the time of its composition and inscription. But the stone itself had been lost. A translation of the Latin reads:

Here the most virtuous mother of a young man set her ashes, a second light to your merits, Augustine. As a priest, serving the heavenly laws of peace, you teach the people entrusted to you with your character. A glory greater than the praise of your accomplishments crowns you both – Mother of the Virtues, more fortunate because of her offspring.

Adeodatus died shortly after his baptism. She had through Augustine no surviving grandchildren. It is not fanciful to think, though, that all those – surely there must be hundreds of thousands – who have converted after reading the Confessions, and all those billions who have found their household in the church which her son did so much to build, and all those whose hearts found rest in the doctrines of God’s grace which he articulated – that all of these, all of us, are her grandchildren.

Ostia: The Road to Rome

-Fin-

Alastair: In the fortnight or so since we last posted here, autumn has fully arrived in New York City. The intolerably sticky heat in which we travelled down to DC for the Protestant Theology of the Body conference has passed, to be replaced by a persistent drizzle. To this Englishman, it almost feels like home!

As does our apartment. We entertained guests here for the first time on Sunday, something which we had postponed doing until most of our boxes had been unpacked and the clutter removed from the hall.

Last week was my last week of travelling for teaching for a while. Besides returning to the UK on October 9th, I will be much more settled for the next few months. Online teaching recommences this Saturday and I am also revisiting various writing projects that I had to put on hold over the summer. If I am fortunate, I might even be able to get into a routine again.

After returning from DC, besides supervisory commitments for several students and a backlog of other work and correspondence, I had to complete my preparation for my Theopolis Intensive course on the Exodus. That occupied much of that week.

On Monday, September 11th, we visited the 9/11 Memorial with our friend Paul Shakeshaft, who was in the city for a few days. We visited the Memorial on the anniversary of the attacks last year too. Once again, it was sobering to reflect upon how they represented a watershed between the world of the 90s and the very different world that we now inhabit, also precipitating and exemplifying many of the changes that would come.

The atmosphere at the Memorial on the anniversary is, unsurprisingly, more pronounced. There were a lot of service people in the vicinity, especially around O’Hara’s Pub. The Tribute in Light, twin beams projected into the sky in commemoration of the towers, was also very moving to see.

We mentioned our visit to the Memorial in our first proper post on this Substack: it is now one year old. We’ve been very thankful to have somewhere to record our adventures: without this Substack, it would be very easy to forget some of the work we’ve done, places we’ve visited, and people we’ve met. Looking back through older posts, we are reminded of how blessed we have been, and how full our life together is.

On Tuesday afternoon, we passed a pleasant couple of hours in the city; it was a beautiful early autumn day and we met up with Paul again and spent some time in Bryant Park and browsing in a bookstore. With the intense travel commitments of my previous US stint, my month back in the UK, and the DC trip, it has been welcome to make the most of living in the centre of NYC again.

Last week was my Theopolis Intensive course on the Exodus: twenty hours of uninterrupted recorded lectures, with lots of extra interaction outside of class time. It was the second Intensive course I had taught. It was quite exhausting, but also welcome to tackle the subject in depth again. In writing Echoes of Exodus with Andrew Wilson a few years ago, I had sent Andrew about 150,000 words of notes, which had been whittled down into around 30,000 words for the book. The course I taught for Theopolis was even more expansive than that. It should be available on the Theopolis App before long.

Although packed with teaching commitments, my visit to Birmingham was also very enjoyable. On the Thursday evening, I attended a delightful performance of The Importance of Being Earnest by students from the Westminster School at Oak Mountain, directed by Christian Leithart.

Before I flew out of Birmingham, one of the students in the Exodus course generously took me around Birmingham Botanical Gardens, which I had not previously visited. If you ever visit Birmingham, you should consider devoting a few hours to a walk in the Gardens. For me, the Japanese garden was the highlight. We visited a restaurant after the Gardens and I ordered some shrimp and grits, not wanting to miss the opportunity before leaving the South.

Among the things I’ve especially appreciated about this stint in the US is the fact that I have been able to attend our church all but one of the Sundays that I have been here; I won’t miss another before I return to the UK. It is very special to be able to visit churches elsewhere, and encouraging to see what God is doing in many different contexts. However, with so much travelling, those occasions when we get to attend our own home church mean a lot more. On Sunday, I delivered the first of three talks on Bible reading skills for a group before the morning service.

One of the most surprising things about the first year or so of marriage has been how few boardgames we’ve played, despite the fact we both love such games. We even have three unopened boardgames that we have yet to play. We spent most of Sunday afternoon chatting, devouring snacks, and playing 6 nimmt! with our friends, the first of many such occasions, I suspect. I am really looking forward to it!

Yesterday evening, Susannah delivered a talk on St Monica of Thagaste, the mother of St Augustine of Hippo, at the Dead Ladies Show. It was superb and you can read it below.

Dido in the Confessions

In other posts, I have addressed objections that some raise against the use of typology, symbolism, and elaborate literary artistry in the biblical histories. The presence of pronounced symbolism, typology, and literary artistry, the argument goes, would compromise the reliability of such accounts as historical reports, revealing them to be elaborate fictions and literary contrivances.

There are many points that can be made in response to such claims, perhaps most importantly that, convenient or not, such symbolism, typology, and literary artistry is clearly present in the biblical text at many points and has been recognized throughout the history of the Church. Though clearly well-intentioned and sincerely held, convictions that they might make our arguments for historical reliability marginally harder than they would be in their absence mostly serve to close our eyes to manifest features of the biblical narratives, lightly jettisoning long-established Christian approaches to the Scriptures for the sake of greater apologetic effectiveness with modern persons.

Nonetheless, concerns about the presence of symbolism, typology, and elaborate literary artistry in historical narrative are understandable and not unreasonable for modern persons to hold. These things really violate modern beliefs about responsible historiography, as we conceive of history rather differently from ancient readers (as Joshua Berman emphasizes). The difference has less to do with a tolerance for fictionalizing than it does with our much thinner conception of what history is intended to be: for moderns, history is not expected to serve as exhortation and the authoritative communication of meaning. For biblical and ancient history, literary artistry, symbolism, and typology all served such an end, presenting events in ways that excited deeper insight and gave authoritative direction.

It can be illuminating to observe the use of such artistry, symbolism, and typology in historical and bibliographical works beyond the Bible. One such work is St Augustine’s Confessions. Although he was writing a faithful autobiographical account, Augustine was concerned to communicate deeper meaning to his readers. Consequently, he carefully crafted his narrative in a way designed to accentuate meaningful parallels and to explore symbolic and typological associations.

Perhaps the most obvious example of this is Augustine’s treatment of an incident from his teenage years, his theft of pears from a garden. While the reader might minimize the affair as a relatively minor instance of juvenile delinquency, Augustine ruminates over his actions and the desires that drove them, treating the episode as one in which the deeper character of sin’s workings can be seen. The attentive reader will appreciate the way that Augustine, in presenting his stealing of fruit as an archetypal sin, develops an implicit parallel between it and the sin of the first couple in the Garden of Eden. They might also recognize an intentional symmetry and juxtaposition between his stealing from the pear tree and the fact that he heard the words that led to his conversion between a fig tree in another garden.

In chapter 13 of Book 1 of his Confessions, Augustine describes how moved he was by the tears of mythical Dido at the departure of Aeneas from Carthage, while being insensitive to his own grave spiritual condition.

For certainty the first lessons, which formed in me the enduring power of reading books and writing what I chose, were better because more solid than the latter, in which I was obliged to learn by heart the wanderings of Aeneas, forgetting my own wanderings, and to weep for the death of Dido, who slew herself for love, while I looked with dry eyes on my own most unhappy death, wandering far from Thee, O God, my life. For what is so pitiful as an unhappy wretch who pities not himself, who has tears for the death of Dido, because she loved Aeneas, but none of his own death, because he loves not Thee?

O God, the light of my heart, Thou hidden bread of my soul, Though mighty husband of my mind and of the bosom of my thought, I loved Thee not. I lived in adultery away from Thee, and all men cried unto me, Well done! well done! For the friendship of this world is adultery against Thee. Well done! well done! men cry, till one is ashamed not to be even as they. For this I had no tears, but I could weep for Dido ‘slain with the sword and flying to the depths,’ while I was myself flying from Thee into the depths of Thy creation, earth returning to earth. And if I was forbidden to read these tales, I grieved; because I might not read what caused me grief. Such lessons were thought more elevating and profitable than mere reading or writing. What madness is this!

Having earlier mentioned this famous episode from the Aeneid, Augustine powerfully evokes it in his description of his own departure from Carthage in chapter 8 of Book 5. Like Aeneas, Augustine departs secretly by night for Rome, so that he won’t be detained by the woman who loves him. The woman left behind in Carthage weeps inconsolably at the loss.

The alert reader should recognize the brilliant way in which Augustine uses the story of Aeneas and Dido and the Aeneid more broadly as an intertextual foil against which to tell his own. Augustine is, like Aeneas, a restless wanderer, seeking a true home. He is shipwrecked in Carthage, detained by a woman’s love, before leaving for Rome.

Augustine’s spiritual wandering and his final discovery of rest in God takes up and purifies the pagan myth of Aeneas. Beyond a simple and sterile transposition of that myth into a frame for his autobiography, by placing the Aeneid and his own story in conversation, Augustine invites us to explore a rich and illuminating interplay between them. The juxtaposition of Dido and Monica, for instance, heightens our sense of Augustine’s insensitivity to the state of his soul and to his own mother’s tears for him. However, in juxtaposing Dido and Monica, Augustine can also alert his reader to the necessity of the parting, as her restless man, unwittingly driven by a greater hand of destiny, must be driven on towards it. Book 5, chapter 8:

The wind blew and filled our sails, and the shore receded from our gaze. There was she in the morning, wild with sorrow, besieging Thine ears with complaints and sighs which Thou didst not regard, for by my desires Thou wast drawing me to the place where I should bury my desires, and her carnal yearning was being chastened by the appointed scourge of grief. For she loved to keep me with her, as mothers are wont, yes, far more than most mothers, and she knew not what joy Thou wast preparing for her out of my desertion. She knew not: therefore she wept and cried, and by that anguish revealed the taint of Eve, seeking with groans what with groans she had brought forth. Yet when she had made an end of accusing my deceit and my cruelty, she fell again to praying for me, and so returned to her house, while I went on my way to Rome.

Monica’s tears are those of a distraught mother, one animated by an unusually strong natural affection. But they are also tears of a Christian mother, who with new groaning seeks the spiritual birth of the child she once delivered in physical pain. As such, her tears are both elevated and efficacious. Unlike the tears of Dido, her spiritual groaning will see its fruit and the gift of her son to her, not chiefly in their physical reunion, but in their spiritual: ‘where you are he will be.’

Through these parallels and contrasts, Augustine is also inviting us as his readers to reflect critically upon ourselves. Monica’s tears in Carthage are not merely a poignant episode, but, as in Augustine’s earlier reference to his tears over the story of Dido, summon readers to a voyage of the soul, investigating the nature of their own affections.

In this faithful history? There is no reason to doubt that it is. However, Augustine’s concern in telling his story exceeded that of merely accurately conveying a series of notable events. He wrote in a manner designed to excite reflection and self-examination. He used literary artistry, symbolism, and typology to suggest, reveal, and accentuate associations and contrasts, all in order that his readers might be led to insight, seeing deeper stories within Augustine’s story and learning how faithfully to tell their own.

The biblical writers do much the same.

Recent Work

Alastair

❧ My one-time co-author and podcast cohost, Andrew Wilson, has just released a new book, Remaking the World: How 1776 Created the Post-Christian West. We devoted an episode of Mere Fidelity to discussing it. The next episode followed up on a thread that was raised in that discussion: Are Mediocre Christians Allowed?

❧ Our Deuteronomy series on the Theopolis podcast continues with episodes on Deuteronomy 17: Priests, Judges, and Kings and Deuteronomy 17: Laws Concerning Israel’s Kings.

❧ On the subject of kings, the recordings of the talks from this summer’s National Convivium have been published, including among them my talk offering theological reflections on the coronation of HM King Charles III.

❧ I’m back on the God’s Story Podcast, with episodes on the seven trumpets of Revelation: part 1 and part 2.

❧ If you want a small taster of some of the material that I covered in my recent Theopolis Intensive on Exodus, you might be interested in this video, the first of a short series.

And this is the second.

❧ One of my lectures from the course, on the Exodus pattern in Scripture, has also been posted on the Theopolis podcast channel.

Upcoming Events

❧ Alastair’s John and Revelation Davenant Hall class begins this Saturday.

❧ Alastair flies back to the UK on October 9th.

❧ Most of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Susannah and Alastair

What a mom.

6 Nimmt! Such a wonderfully infuriating game.