№ 11: Venetian Sojourn

In which Susannah does something truly ridiculous. On not hearing the Bible as 'history'.

Dear Friends,

Those of you who know our backstory know that Alastair and I got together right at the beginning of COVID. Like everyone, I’d heard about COVID - but it was a news story until the morning of Sunday, February 23, 2020, when I woke up in Venice to find the city full of carabinieri wearing masks, to the news that that coming night’s party would be the last of Carnevale, the final two nights being cancelled.

Alastair had been planning to come to Trieste to visit me at an apartment I was meant to have through the end of February. But anyone coming to Northern Italy in late February of 2020 was, it quickly became apparent, a bad idea. So I went to England instead, and by the time I left eight days later, we were a couple.

(I very nearly got myself stranded in Europe because a) it seemed romantic and b) I was neurotically worried about being Patient Zero in NYC, but by that time, NYC was already undergoing its first spike, nearly as bad as Italy itself, and everyone was being told to get back to their home countries, so I skedaddled home.)

In 2021, Carnevale was cancelled entirely, and in 2022, Alastair and I were deep in the throes of wedding planning during February, so this year was my first time back.

Carnevale is the week or so leading up to Mardi Gras, Shrove Tuesday, the day before Ash Wednesday, the beginning of Lent. Carnevale in Venice is distinctive: it’s not the mad rager with floats and beads that you get (I’m told) in Rio or New Orleans; it’s instead a series of historical and themed private costume parties, decorous, but absurd in their own way. The music tends to be period - baroque for Versailles, English country dances for the Regency party - and to change to contemporary stuff later in the evening (Boney M is heavily represented.)

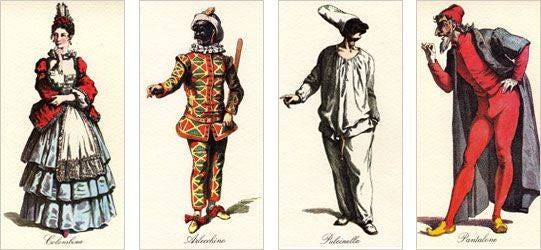

The characters in which people appear vary wildly, but many of the most common ones come from Italian Commedia dell’Arte - you get Harlequin and Columbine, Pulcinella, Pantalone, Pierrot (a French import), Il Capitano, and, ominously in 2020, Il Dottore.

I don’t actually know if before 2020 he was very frequently cast as a plague doctor with the distinctive “crow” mask, but that’s what he’s evolved to now.

But there are as many other characters as there are obsessive historical costuming weirdos throughout Europe and America. The most common era, the sort of Carnevale Ground State, is late eighteenth century. But different parties call for different costumes.

This incarnation of Carnevale actually dates back to 1979, and the parties we go to are friend-group parties that have been passed down since then, held in rented palazzi.

The first day I got there, though, I had a small dinner with friends. But before THAT, we had to do what you do before every party: wherever else you end up, whatever else you’re doing, first you have aperitivo at Caffe Florian.

Founded in 1720, Florian was most famously the haunt of Casanova; today, it’s where you meet before each party.

That first night, we went afterwards to Il Poste Vecchie, a restaurant founded in 1500 where, yes, Casanova also apparently ate (he’s not as prevalent in Venice as Mozart is in Salzburg but it’s a similar kind of thing.)

The rest of the week was parties - not every night for me; I was, by certain definitions, moderate. And I even did work during the day; it’s very possible.

Throughout the week, throughout the city, in all the calli and campi, people are in costume. The whole city becomes a party - again, not in a crazed way; people bow to each other in the street, and curtsey, or avert their eyes mysteriously.

But the best thing about Venice isn’t the parties and it isn’t the costumes: it’s the city itself. It’s magical - which is a silly and easy thing to say, but it’s true. For those of you who’ve read Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi (and I know that’s a lot of you, what with the rash of Piranesi-reading that happened in 2021), Venice is the House: it’s a city that’s a unified thing, like a single palace, full of strange statuary and with its ground floor awash in a tidal sea.

Like the House, it is filled with meaning. It isn’t just a place like a geographical fact; it’s a place like an intention, like the setting of a story, like a story itself.

When I went in 2020 I wandered around in the slightly dysfunctional daze that one gets in a new city when one doesn’t speak the language. This time was different: I felt as though I knew how the city worked, and indeed in general I got where I needed to be and got done what I needed to get done.

But - and this was crucial - what I didn’t have was cell service. I’d just gotten a new phone before leaving the States; it was time, and I got it for more or less free. But Verizon locks your phone for sixty days from the time they transfer your plan to a new one, for esoteric business competition reasons, presumably, so you can’t just hit them up for the latest iPhone and then trot off to get a TMobile plan.

And so no Italian SIM card for me. And in the painful process of discovering this, in various TIM and Vodaphone kiosks throughout Venice, somehow my Verizon plan itself got de-linked from my new phone. (This took six hours on the phone to Verizon to finally fix two days ago).

So basically what I had was a tiny computer which could get WiFi, if there was WiFi around, but no cell service for love or money.

There was WiFi in precisely two places (that I knew of, eventually): my AirBnb, in the garret of a crumbling palazzo on the Grand Canal just off the San Marcuola vaporetto stop, and the Hard Rock Cafe off the Piazza San Marco.

What this meant was that, for the entire time I was in Venice, I was a Normal Human Being. I had to live like - well, like we used to live. Like Casanova lived, and Mozart, and like your parents lived, and like you may remember living.

My friends, I used a paper map. I had to ask directions. I had to make plans, and stick to them. I had to orient myself and have a sense of direction. I had to NOT BE GORMLESS. And I had to do it all whilst wearing 18th century stays, which isn’t backwards and in heels, but it’s not nothing.

It wasn’t exactly like an Outward Bound orienteering experience where you have to make fire with sticks and a bowie knife and catch animals and eat them, and navigate by the moss on trees, or whatever it is you have to do, but it wasn’t exactly NOT like that either. (There was, I’ll say, a good deal more lip stain and Prosecco than there is on an average Outward Bound trip – again, from what I understand.)

I know that when you opened this Substack what you were not really looking forward to was an account of my cell service troubles, but that’s not the point. The point is - this was seriously a Matthew Crawford-style Shop Class as Soulcraft experience, I was interacting with the physical world in an unmediated way; this was character building stuff, man. I am now a better person, slightly (though to be honest it was probably balanced out by the Versailles party on the final night.)

I recommend it to all of you, though there may perhaps be more straightforward ways of accomplishing the same thing (turning off your phone I guess.)

Anyway, it was a lovely time, and I am now of course deep in the Carnevale friend group groupchat planning next year’s costumes, and this is all very ridiculous, and I could make a strong claim about the crucial importance of Carnevale for the Christian liturgical year, and it wouldn’t be wrong, but I’ll skip it. You can find that elsewhere.

Now I’m back home in Staffordshire, and Alastair and I went for a walk yesterday after church. And the crocuses are in bloom.

Meanwhile, the “Pain and Passion” issue of the magazine has launched, and while there are many things that I’ll highlight for you in our next issue, I am very proud in particular of Pete’s interview with Tom Holland here.

Recent Work

Alastair: The past fortnight was one during which the vast majority of my work was for some exciting long or medium term projects that won’t appear for a while, in teaching and meetings, catching up on correspondence, rearranging my shelves to accommodate Susannah’s growing library in UK, or assisting in various friend’s projects. I also updated my computer, bought a bike from a neighbour, and started a new knitting project.

That said, I have kept up with my regular podcasting.

❧ Abigail Favale, the author of the recent book The Genesis of Gender: A Christian Theory joined us on Mere Fidelity for a discussion of her work and the topic of sex, gender, and prevailing gender theories and paradigms. At Matt’s request, we also had an in-house discussion of 2 Thessalonians 2, the identity of the Man of Lawlessness, and how this can be integrated into the framework of New Testament and biblical eschatology more broadly.

❧ The Theopolis Podcast’s series on James Jordan’s seminal book Through New Eyes continues with episodes on the World of the Temple and the Worlds of Exile and Restoration.

What We’re Reading: On Not Hearing the Bible as ‘History’

Alastair: A week ago, I was privileged to make the online acquaintance of Ezra Zuckerman Sivan, whose work on the relationship between the story of David and Bathsheba and the story of Judah and Tamar I mentioned in our previous Substack post. In an incredibly stimulating and expansive conversation on Zoom, he recommended some of the work of Joshua Berman to me and, over the last few days, I’ve been enjoying dipping my toes in some of Berman’s work, more specifically parts of his Created Equal: How the Bible Broke with Ancient Political Thought, his Ani Maamin: Biblical Criticism, Historical Truth, and the Thirteen Principles of Faith, and his Narrative Analogy in the Hebrew Bible: Battle Stories and Their Equivalent Non-Battle Narratives.

Berman is an observant reader of Scripture, with perceptive insights on many passages. For instance, a few days ago I was a guest on a podcast on which I discussed the unsettling story of the Levite and his concubine in Judges 19, a passage to which Berman devotes a chapter in Narrative Analogy in the Hebrew Bible.

In her ground-breaking work on the book, E.T.A. Davidson has observed the way in which the narratives of Judges routinely function as glosses or commentary upon each other and upon other scriptural narratives. Without an appreciation of this, much of the richness of the book will pass us by. For instance, Delilah’s attempts to get Samson to reveal the secret of his strength are designed to recall Samson’s earlier feats, while the 1,100 pieces of silver in the story of Micah in chapter 17 should remind us of the same sum in the story of Samson in the preceding chapter.

Paying close attention to shared vocabulary and symmetrical events, Berman comments upon the way that the story of Judges 20-21 and the war with the Benjaminites replays the themes of the story of the Levite’s concubine. Both the concubine and the Benjaminites are the victims of some evil or disaster (19:23, 20:12/20:41), encircled (19:22/20:43), hunted to exhaustion (19:24-25/20:43), abused (עלל—19:25/20:45), fall (19:26, 27/20:44, 46—נפל), and are cast (19:25/20:48—שׁלח). Both meet their demise in connection with the sun's rising (19:25, 26, 27/20:43), destroyed on the threshold of their former shelter, the concubine outside the house and the Benjaminites just outside of Gibeah (19:25/20:43-44). Israel reflects upon both events similarly (20:12/21:3). Look more closely and further parallels emerge, such as the fact that both the concubine and the Benjaminites flee to a place where they remain for four months (19:2/20:47). Recognizing such parallels, the attentive hearer will be led to ponder upon what they might mean.

Perhaps one of the areas where Berman is most helpful is in his criticism of higher criticism (my first exposure to Berman was likely his introduction to Umberto Cassuto’s The Documentary Hypothesis and the Composition of the Pentateuch). While there are aspects of Berman’s approach with which most conservative Christian readers would take issue, his defence of Scripture against the charges of higher critics is powerful and he puts his finger on some crucial issues with which all thoughtful readers of Scripture—Christian or Jewish, liberal or conservative—should engage.

In the past, I have observed that modern conservative and liberal Christians largely share assumptions concerning history that seem to be foreign to the scriptural text. Even though the text intends faithfully to bear witness concerning concrete events that occurred in time and space, the way the authors of Scripture and its original readers seem to approach this is strange to moderns, violating many of our basic conceptions of the sort of thing that history is. It is this that Berman most highlights.

Berman reminds us that concepts and categories have origins and developments and that many of those we take for granted in the modern world may be without straightforward precedent or clear analogy in the Scripture or the world of its authors. He gives the examples of ‘belief, law, history, author, fact, fiction, story, religion, and politics’ [xxiii, emphasis original]. While not altogether without parallel within it, none of these concepts as they function in the modern world can simply be mapped onto concepts that were operative in the world of the Scriptures. Without appreciation of this, it is easy to impose anachronistic demands and expectations upon the Scriptures, demands and expectations that—whether in the conservative cause of salvaging them from criticism or the liberal cause of savaging them with criticism—may lead us to distort or discount Scriptures that could fruitfully be understood on their own premodern terms.

Berman lists some of the underexamined assumptions with which we are accustomed to approach a supposed work of ‘history’: the assumptions that we hold concerning the content of such a work, the author of such a work, and ourselves as readers of such a work. Regarding the first, the content of such a work, Berman points out the way that rhetorical flourishes, symbolism, embellishment, and preaching or moralizing are all deemed inappropriate in works of history by moderns. On the second, the authors of works of history, Berman observes the way that we expect historians to be masters of the academic discipline of history and its critical methodology, but do not believe that they are thereby warranted to command or demand anything of us as their readers. Finally, readers of history approach their reading material as consumers and judges, who read voluntarily as those who reserve to themselves the right to be the arbiters of the meaning of the events recorded. ‘In our world, the historian or journalist provides the facts; the reader determines the meaning’ [19].

Berman argues that this approach to the writing and reading of history is more peculiar to the modern age. Premodern ‘history’—within Scripture and in other ancient histories—was chiefly exhortation:

These writers never wrote with the disinterested aim of chronicling the past for its own sake. Rather, the deeds of the past were harnessed for rhetorical effect to persuade readers to take action in the present, to believe in the powers of a deity to deliver salvation, to exhibit bravery or other civic virtues. [20]

A person was qualified to recount the deeds of the past, not chiefly on account of their mastery of historiography, but on account of their standing in the community (as office holders, military heroes, esteemed men of letters, etc.). Unlike contemporary historians, they weren’t expected to provide a full account of their sources or to prove in detail the accuracy of their claims. Berman notes:

In our world, the primary encounter is between the reader and the facts he or she reads. In the pre-modern world, the primary encounter is between the reader and the authority of the exhorter. [24]

Their accounts were not expected to be clear and unembellished presentations of carefully sourced and substantiated facts, with minimal rhetorical flourish, symbolism, and literary artistry, their interpretations of events being submitted to the judgment of their readers. No, as texts written chiefly to exhort, by figures with standing in their communities, they addressed their hearers or readers with authority, giving their accounts of events in ways designed to persuade and to move their audiences in the present.

This approach might in certain respects be closer to a modern historical movie than a modern academic work of history. Such a movie, even while it may seek to be very faithful to the reality and require extensive research, won’t provide detailed sources, allows a degree of embellishment, reordering, and dramatizing of its material, is artistically designed to move and inspire its audiences rather than merely to inform them, and doesn’t approach those audiences primarily as judges of the history that it portrays. Historians watching such movies may applaud the faithfulness of their portrayals, while recognizing that the faithfulness of such works will be assessed by rather different, even if not entirely foreign, criteria from those applied to their own. Of course, in other respects Scripture is a very different thing from such modern artistic portrayals of past events so, in avoiding the limitations of one modern analogue, we should beware of thoughtlessly adopting the limitations of another.

Any attentive reader of Scripture shouldn’t take long to recognize that, even though it is very concerned faithfully to communicate past events and is also often written by eyewitnesses of some of those events (and/or persons who knew several such eyewitnesses), it is very different from the kinds of historical writing to which we are accustomed (and much more akin to the historical writings of its own time). The accounts of Scripture don’t, as contemporary histories, humbly present their account of the facts before the bar of the discipline of history, their reliability and meaning to be judged by their hearers according to principles of sound method. No, they speak as authoritative and trustworthy witnesses that call for faith from their hearers.

Those accustomed to trying to get ‘behind’ various historical accounts to discover the underlying facts and adjudicate competing interpretations will frequently be dismayed by the degree to which Scripture obstructs their way, leaving us little choice but to submit to or disregard its authoritative testimony. While harmonization of accounts may be possible and we should not presume embellishment, Scripture routinely portrays events in ways that seem more concerned to communicate their theological import than the simple facts of the history. What was the nature of Judas’s death? Matthew and Acts give us very different accounts and, while they can be harmonized, the difficulty and awkwardness of such harmonization suggests that Matthew and Luke were rather less interested in the supposedly pure historical details of Judas’s suicide—‘what actually happened’—than in portraying the event so as to accent aspects of its theological and typological import.

Of course, the theology and typology must be grounded in real events, but textual mediation is inescapable. While assuring us of the grounding of our faith in concrete historical realities, Scripture portrays events in ways that neither invite nor really facilitate reconstruction of ‘what actually happened’, as moderns can tend think of this—as discrete and unadorned facts detached from frameworks of meaning and authority. Its account of the past is not a recounting of historical facts but an authoritative portrayal designed to summon people to faithfulness in the present and to equip them to perceive the meaning of events.

In reading the Scriptures ‘as history’ (in the modern sense of that term), both liberals and conservatives can fail to treat them on their own terms. Conservatives, for instance, in reading biblical narratives as ‘history’, frequently miss their theological, typological, symbolic, literary, and hortatory character. The ‘authority’ of such narratives can get thinned down to their reliability as historical sources in the modern sense. On the other hand, those who appreciate the literary artistry and symbolism of the biblical narratives can lurch towards dismissing them as faithful accounts of the past.

While Berman’s approach to these issues differs from mine, he identifies the crux of so many of the problems with modern readings of Scripture, whether conservative or liberal.

Upcoming Events

❧ This Saturday we plan to be in Shrewsbury for a walk and pub lunch with Tim Vasby-Burnie and others. If you are interested, sign up here.

❧ Tim has also arranged a 'Psalm Roar' at St. George's Church in Shrewsbury for the 22nd April. The evening before, I'll be delivering a talk on the theology of the psalms and of psalm-singing. Sign up for the event here!

❧ The forthcoming Theopolis Workshop on ‘Numberology’ is still open for registration, as is the Davenant Hall course on ‘A Biblical Theology of the Sexes’.

❧ Alastair will be returning to Davenant Hall to teach the summer program in June.

❧ Most of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Susannah and Alastair

Alastair, I cannot say I truly understand the entirety of what you've written here, but it doesn't mean I don't appreciate it. As I alluded to in another comment, I had a crisis of faith in seminary, and it wasn't until I found and fell in love with the early church fathers and mothers that I found my footing again. However, it doesn't mean I don't struggle to wrap my head around this very topic, that our views of historicity are foreign to the biblical writers, yet that doesn't mean the texts are errant or flawed. I've just had to learn what it means to have faith that the words we've been given are tried and true. Not a mindless and heartless faith, mind you, but one that has been tested, time and time again.

I've also learned as a parent, even if I *did* believe the Scriptures were errant, I don't think I could ever teach my children that Jesus is the way, the truth, and the life, but also say we can't trust the Bible as the Word of God in the same breath. Not saying that's the only reason I believe what I do, but it definitely made me reckon with it all.

I've just read this post after following the link from your most recent update.

I am currently wrestling a great deal with many of the issues of the relationship between history and artistry described here and in your recent post.I really resonate with what David Marshall says above and suspect I am I a very similar place.

I found all you have said above helpful.

I would love to understand better. I'd be very grateful if you could point me in the direction of articles/books you think explore the issues well.

Thanks for all the time you find to serve random readers in your busy schedule.