№ 54: Foraging and the Fall

Non-Pauline biblical theologies of the Fall

Alastair: We are just about to travel back to the US for a brief stint, and have an intense schedule for a couple of weeks.

[Susannah: I am not at all clear that he didn’t choose this title for the Substack as a deliberate ambiguity.]

The time since we posted our last Substack, on August 30th, while full and active, was also a refreshing return to more settled life. Since the beginning of June, we have had a succession of stimulating and enjoyable yet exhausting trips and events, and have desperately needed to catch our breath. While we have been snatched away from it again, the slower rhythms of life in Stoke-on-Trent have afforded us a welcome respite.

Although I appreciate travel and being in different places, there are few things I value more nowadays than a more settled routine and sleeping in our own bed, especially as so much of our life is on the move. Despite our peripatetic and highly social lifestyle, by temperament I can be quite an introvert and homebody; indulging that from time to time is not unwelcome. I have been teaching my latest Davenant Hall course, have preached in our church, supervised students, recorded podcasts, read books, prepared talks, written articles, and spent time with my parents. We have done some radical organization of the house and have sorted out several tasks that had been hanging over us.

The Chatsworth County Fair was on at the end of August and, having visited Chatsworth a couple of weeks earlier, Susannah was excited to go to it. We invited my brother Peter and his wife but, as she could not make it, a friend of theirs joined us instead.

Peter picked us up in Stoke. We drove through Leek and out into the Peak District, past the Roaches and some other memorable walking spots.

There are few things more lovely than the scenery of the Peak District, whether bathed in the bright noonday light which, dappled by scudding clouds, randomly accentuates the various features of the landscape, or seeing those features afire in the warm hue of a sinking sun. Looking out over it, the sense of space is exhilarating.

While I have done a fair amount of walking in and exploration of the Peak District in the past, Susannah and I really have not done much together. Travelling through the countryside and passing its picturesque villages, we are more determined to do so in the future. Being surrounded by such beauty lifts the spirits.

The fields in front of Chatsworth House were a sea of cars. We found a place to park, crossed a bridge and entered the fair. Just past the entrance were dozens of old military vehicles and some military reenactors, all eager to tell visitors something about the groups they were dressed up as.

I am not sure that I have ever visited a fair as extensive as the Chatsworth County Fair. There were many hundreds of stalls, with a vast array of food, country wear and other outdoor clothing, clubs and societies, craftspeople selling their wares and demonstrating their skills, and anything else that you (or your dog) could wish for. Besides this, there were historic vehicles, carnival rides, exhibitions and a large range of competitions and events.

We immediately went to some of the food stalls, from which we bought lunch. The fair was so vast that we knew we could only experience a limited amount of it, but threw ourselves fully into experiencing the things in front of us and did not worry overmuch about anything that we might be missing.

We saw some military bands with drummers and pipers competing and, in the grand ring, a dog herding geese.

Beyond the grand ring, there were stalls with birds of prey, conservation groups, a man with ferrets, people demonstrating historic farming equipment, fencing techniques, and many other such things. [Susannah: Fencing as in rural barrier building, rather than swordfighting, sadly.]

We were thrilled to discover that the British Stickmaker’s Guild is a thing that exists. Such an organization answers to a natural impulse deep in many young boys’ hearts.

The fair had much in common with an American county fair, but was also quintessentially English in countless ways. There were throngs of people spread over the 122 acres of the showground, with practitioners of heritage crafts, and a sense of ways of life, people, places, and traditions that go back centuries.

We spent an hour or so exploring the stalls before returning to the grand ring, where there were more military marching bands and some delightful mischief and mayhem with dogs. As stores were preparing to close, I was also given a batch of remaining fudge that one store owner was about to throw out. [Susannah: He was SO excited about this.]

We decided to leave a little earlier, before the main body of traffic departed from the fair. We drove to the nearby town of Bakewell, famous for its eponymous tart, visiting The Old Original Bakewell Pudding Shop. We wandered around the town for a while, ending up in a pub, where we enjoyed a pint. [Susannah: The Eponymous Tart sounds like the title of a racy Restoration comedy. Something by Congreve.]

It had been raining earlier, but it stopped, the sun came out, and we were treated to a rainbow. Bakewell is a charming little town, with lots of limestone, sandstone, and gritstone buildings that one would associate with the Peak District. The stone captures the warmth of the evening light, giving the place a magical glow.

Peter wanted to go straight back to Manchester, so we drove back to his house, giving us the opportunity to say hi to my sister-in-law, who had been unable to join us. Susannah was also able to cuddle one of their rabbits. Peter then dropped us off at the train station, where we caught the train back to Stoke.

The next week was a busy one, within which we enjoyed a settled routine. We visited my parents a couple of times and got a lot of work done.

As I mentioned in our previous Substack post, I discovered a huge crabapple tree in one of our local parks. On the Wednesday, Susannah and I returned to it. Susannah discovered that the park has a huge selection of fruits, berries, and the like—crabapples, damsons, pears, haws, sloes, blackberries, etc.—and something clicked into place in her subconscious.

I introduced her to an app that helps one to identify plants and their uses and, in the one concession that she has made to the usefulness of AI, since then she has been using it incessantly and compulsively to discover every single useful plant or tree in our vicinity. [Susannah: This is how the robots get me. In my very attempt to touch grass. Just shameful.]

Foraging has been the absolute dominant theme of the past fortnight. We have spent hours exploring the park, picking fruit and berries, and identifying various plants and trees. While living in the city, we are immensely grateful to have so many places to forage on our doorstep, within five minutes’ walk of our house.

On the Saturday we left Stoke early and travelled down to London, where we were going to spend the weekend. We wandered from Euston Station to Foyles, where we browsed for a while, before going to Piccadilly Circus and down Regent Street St James’s and across the Mall towards St James’s Park.

Walking alongside Horse Guards Road, we saw a crowd gathered opposite the Churchill War Rooms. From what I later gathered, they were filming part of Greta Gerwig’s forthcoming adaptation of The Magician’s Nephew. I suspect that the scene was the pursuit of Queen Jadis, but set in the 1950s, rather than the Edwardian period of the original novel.

We met up with some friends at the Emmanuel Centre, from which we made our way, past Westminster Abbey, towards Parliament Square and the Houses of Parliament.

We made our way to our friends’ house, where we were having dinner and staying that night. They have an adorable new baby and, as we had not yet met him, Susannah was very eager to make his acquaintance! Our high expectations were not disappointed.

The next morning, we went back into the centre of London, having a full English breakfast at a pub near Paddington Station. We walked to St Paul’s Cathedral, where we worshipped.

An Excursus on Watling Street

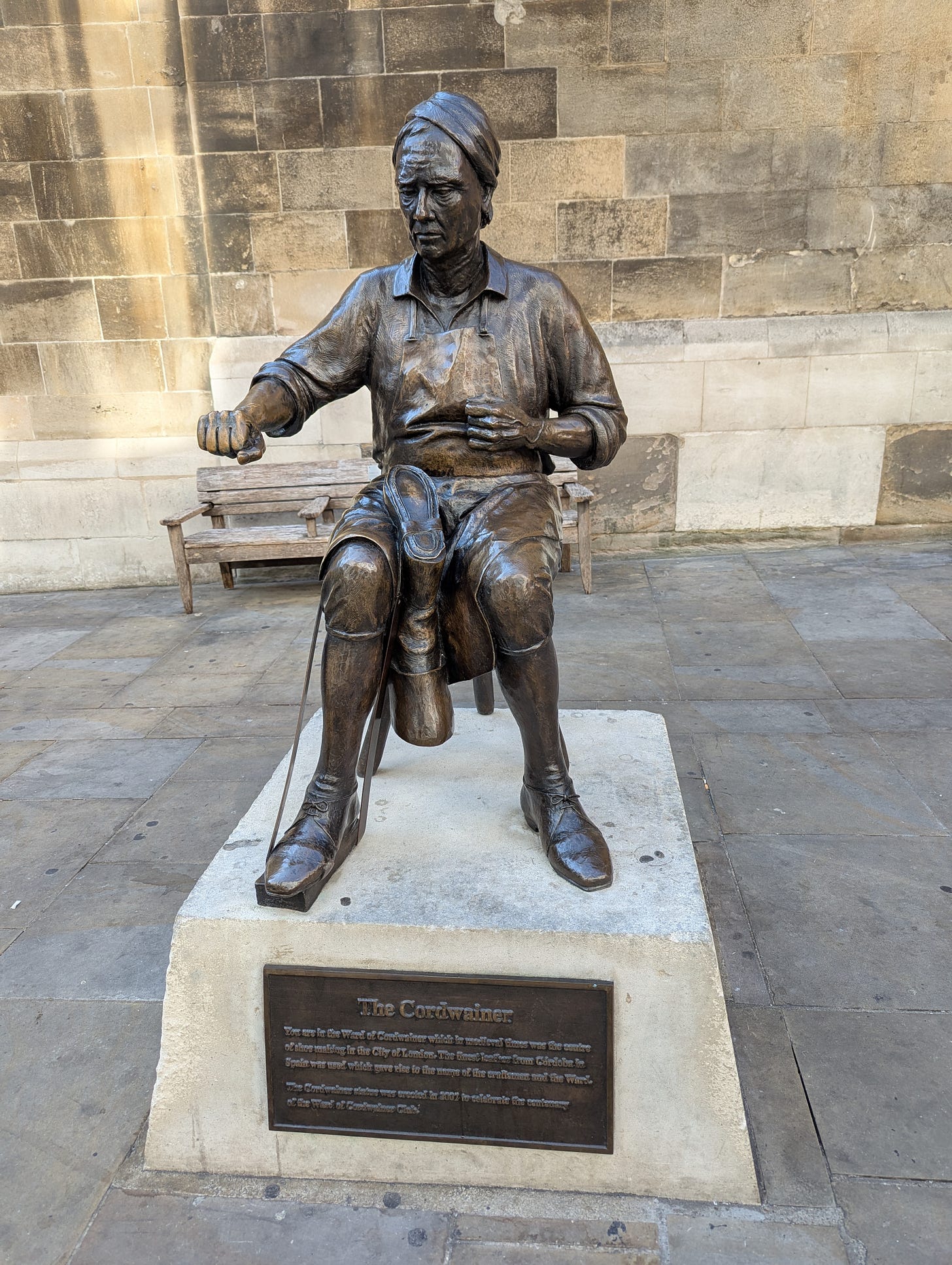

Susannah: To get to St. Paul’s from Paddington, you end up walking down Watling Street (or you do if you get a bit lost, anyway.) It is an unassuming street, lined with dog-friendly pubs and upmarket coffeehouses, a butcher, a nail salon, a sushi place. It is also one of England’s main paved Roman roads, which had been established as a main road on this island for centuries before the Romans came.

Watling Street starts at Dover on the English Channel and runs Northwest to London, where it crosses the Thames, and then North and West again nearly to Wales, ending at the bank of the Severn. The crossing (probably) used to be a natural ford from just about where St Thomas’ Hospital is in Lambeth to what was called Thorney Island, where Westminster Abbey is. The Tyburn, the tributary of the Thames that cut the island off from the rest of the city, was culverted and covered in 1848 and now enjoys a useful if considerably less picturesque life as the King’s Scholar’s Pond Sewer.

Iron Age and maybe even Bronze Age Britons walked the route we were walking. After AD 43 Roman legions walked it, and paved it. It was along Watling Street, about 100 miles up the road from London, in AD 62, that the Roman governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus defeated Queen Boudicca’s ill-fated rebellion.

Just a few yards from the dog-friendly pub and the sushi place is the office building of Bloomberg’s European headquarters. It’s built, as is the case with so many modern London buildings, on the site of a bomb crater, a souvenir from the Luftwaffe. It took London years to rebuild after the war, and it wasn’t until 1954 that a marble head of the god Mithras was unearthed on the site, on the last planned day of a dig that archeologists were attempting to get in before the city’s strata were once again sealed over by owned and lived-in buildings. The find of the head led the team to look more closely at the site, and what they found was the remains of a Mithraeum, a temple to Mithras built by a Roman Londoner some time in the 3rd century AD. The cult of Mithras was wildly popular with the Roman Legionaries, and so it makes perfect sense for the strange, underground, windowless worship space to be built along the street that was Londinium’s lifeline to Rome.

After Roman government stuttered, faltered and then finally failed, the road, well-paved and wide, remained as a reminder of that civilization.

In 383, Magnus Maximus had been governor of the province of Britannia; he did the late Roman Empire thing of attempting a bid at imperial power, and somewhat surprisingly succeeded. But the way he succeeded was to bring his troops, all the legions he was meant to be using to keep the Pax Romanum in Britannia, to Gaul, where he did battle with and defeated the Western Roman Emperor, Gratian. Local warlords took charge, presumably; in 410, the British rose up against and deposed all Roman government officials. They sent an appeal for military assistance to Emperor Honorius. He refused. Even if he had wanted to help, he couldn’t. Imagine being a Briton in, say, 411 AD, seeing one of those Roman paving stones heaved up by.one winter’s frost, and realizing that the army and empire that had laid it down would not be coming to make the repair.

The name comes from this time — from the several centuries of semi-anarchy after the Romans left. Wæcelinga Stræt as a name is an encapsulation of what this time was like: Stræt was the Old English word for any paved as opposed to dirt road, and it comes from the Latin Strata; Latin and paved roads, the Anglo-Saxons understood, belonged to the same world. The Wæcelingas were a tribe: the people of Wæcla (and who was he?) whose home ground was near the Roman city of Verulamium in Hertfordshire. Bede, writing in Latin in 731, refers to the city as Verulamium; it comes up in his account of the England’s protomartyr, Alban. He writes:

Passus est autem beatus Albanus die .X. Kalendarum Iuliarum iuxta ciuitatem Uerolamium, quae nunc a gente Anglorum Uerlamacæstir siue Uaeclingacæstir appellatur, ubi postea, redeunte temporum Christianorum serenitate, ecclesia est mirandi operis atque eius martyrio condigna extructa.

The blessed Alban suffered death on the twenty-second day of June, near the city of Verulamium, which is now by the English nation called Verlamacaestir, or Vaeclingacaestir, where afterwards, when peaceable Christian times were restored, a church of wonderful workmanship, and altogether worthy to commemorate his martyrdom, was erected.

A century and a half years later, in the late 9th century, King Alfred commissioned an an Old English translation of Bede: this was part of Alfred’s mini-Renaissance, his DIY end of the dark ages, an attempt to translate major works from Latin into English to help his subjects have access to the Christian and classical works. That translation is the one that gives us Wætlingaceaster: another one of those evocative names. Ceaster is from the Latin Castrum, for military camp, as in Winchester and Westchester, and Verulamium had indeed been such a fortified town, with the usual Roman complement of forum, basilica, and theater; with the usual amenities of heated baths and flush toilets, fully connected to the imperial hub by the cursus Romanum. In the months before her defeat, as Tacitus tells us, Boudicca had sacked and burned the town, around the same time that she burnt London, and a layer of black ash can be found in the soil of the fields around the town that is now named St. Albans.

Alban was a Roman citizen of some note, living in Virulamium at around AD 300. Things were heating up for Christians at that time — it might have been related to Diocletian’s persecution that began in 303, or it might have been some more local crackdown. A Christian priest, fleeing from a Roman official, seeks shelter in Alban’s house. Though he is a pagan and not particularly interested in the new religion, he hides the priest; they talk; and as the weeks go by, he is converted. The soldiers are approaching, and Alban switches clothes with the priest, presenting himself as the man they’re looking for, and the priest escapes. The soldiers lay hold of him and bring him before the Roman judge, who realizes the switch that has been made, and is outraged at Alban’s apostasy from the worship of the Olympians and disrespect of Roman authority.

Bede tells what happens next like this:

When he saw Alban, being much enraged that he should thus, of his own accord, dare to put himself into the hands of the soldiers, and incur such danger on behalf of the guest whom he had harboured, he commanded him to be dragged to the images of the devils, before which he stood, saying, “Because you have chosen to conceal a rebellious and sacrilegious man, rather than to deliver him up to the soldiers, that his contempt of the gods might meet with the penalty due to such blasphemy, you shall undergo all the punishment that was due to him, if you seek to abandon the worship of our religion.”

St. Alban, who had voluntarily declared himself a Christian to the persecutors of the faith, was not at all daunted by the prince's threats, but putting on the armour of spiritual warfare, publicly declared that he would not obey his command. Then said the judge, “Of what family or race are you?”—“What does it concern you,” answered Alban, “of what stock I am? If you desire to hear the truth of my religion, be it known to you, that I am now a Christian, and free to fulfil Christian duties.”—“I ask your name,” said the judge; “tell me it immediately.”—“I am called Alban by my parents,” replied he; “and I worship ever and adore the true and living God, Who created all things.”

After our records once again get better, after the confusion of tribal hunting grounds and little Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and landholdings that succeeded the Empire’s retreat, after the waves on waves of Vikings finally showed signs of wanting to settle down from their centuries of piracy and rapine, Watling Street remained: it was the Northeastern boundary of Mercia and of Wessex, and thus the Southwestern border of the Viking settler kingdom that Guthrum established. After the Battle of Edington in 878, it marked the Southwestern border of the Danelaw, the region that by King Alfred’s treaty with Guthrum was to be governed under Danish law in exchange for the allegiance of the ex-Vikings, now attempting to be law-abiding farmers, to the Anglo-Saxon crown.

It was the Northern and Western boundary too of the Forest of Arden, the great wood that encompassed much of Warwickshire, and parts of Shropshire, Staffordshire, and Worcestershire, unless indeed it was Cockaigne, or Arcadia. Its distinct character lies in the fact that it is bordered by, but not served by, the Roman roads. It is enclosed by them: Icknield Street, the Salt Road, the Fosse Way, and Watling Street. But they don’t run into it. It is a heart at the center of the island. It is where the action of As You Like it is set, and where Amiens sings:

Under the greenwood tree

Who loves to lie with me,

And turn his merry note

Unto the sweet bird's throat,

Come hither, come hither, come hither:

Here shall he see

No enemy

But winter and rough weather.

Who doth ambition shun

And loves to live i' the sun,

Seeking the food he eats,

And pleased with what he gets,

Come hither, come hither, come hither:

Here shall he see

No enemy

But winter and rough weather.

Icknield Street, the Fosse Way, and Watling Street, as well as Ermine Street, were the four roads in England protected by the King’s Peace under the Laws of Edward the Confessor. Although the text of the laws we have is almost certainly specious, the peace itself, and the special status of the four ways, are likely accurate.

On October 15, 1066, the day after his great battle, William of Normandy went from Hastings to Dover, and then followed Watling Street toward London. He’d killed King Harold Godwinson and expected to be able to just waltz in to the city, but the Witengamot had hastily proclaimed Edgar Aetheling as king. This put backbone into the English, and the defiant Londoners and men of Kent, confronted William’s Normans at Southwark, preventing him from continuing along Watling Street across the Thames.

The spot where they denied him access to the ford was just about exactly where the Tabard Inn was built, 241 years later, in 1307. We have a description of the inn from some 80 years after this, when the innkeeper was a man called Harry Bailey (which is also George Bailey’s younger brother’s name, from It’s a Wonderful Life.) The description goes like this:

Bifil that in that seson on a day,

In Southwerk at the Tabard as I lay,

Redy to wenden on my pilgrymage

To Caunterbury with ful devout corage,

At nyght were come into that hostelrye

Wel nyne and twenty in a compaignye

Of sondry folk, by áventure y-falle

In felaweshipe, and pilgrimes were they alle,

That toward Caunterbury wolden ryde.

The chambres and the stables weren wyde,

And wel we weren esed atte beste.

And shortly, whan the sonne was to reste,

So hadde I spoken with hem everychon,

That I was of hir felaweshipe anon,

And made forward erly for to ryse,

To take oure wey, ther as I yow devyse.

That way, the way taken by Chaucer’s pilgrims, from Westminster to Southwark down South and East to Canterbury, was also the way that Thomas Becket himself traveled dozens of times back and forth from his episcopal seat at Canterbury to his audiences with an increasingly enraged Henry II. It was, of course, Watling Street.

Susannah had never properly visited St Paul’s before, although she had often seen it from outside. The cathedral is one of London’s most iconic buildings, a Baroque building designed by Sir Christopher Wren to replace the earlier cathedral, which had been destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666. Until the building of Liverpool Cathedral in the twentieth century, it was the largest church building by area in the UK. I suspect that many of you have seen pictures of it amidst the smoke of the Blitz.

It was the tallest building in London for over two hundred and fifty years, only being surpassed in 1963. It now no longer makes the top hundred tallest structures in the city. Nevertheless, thanks to planning law its defining presence on London’s skyline is preserved in various ways, particularly in the form of eight protected sightlines (from Alexandra Palace, Parliament Hill, Kenwood House, Primrose Hill, Greenwich Park, Blackheath, Westminster Pier, and Richmond Park), which no new construction can obstruct.

We climbed up to the famous Whispering Gallery, where, beneath the cathedral’s vast dome, a whisper in one part of the gallery can be heard clearly in another, as the soundwaves cling to the walls. The phenomenon of St Paul’s Whispering Gallery was explained by Lord Rayleigh, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist, in the 1870s.

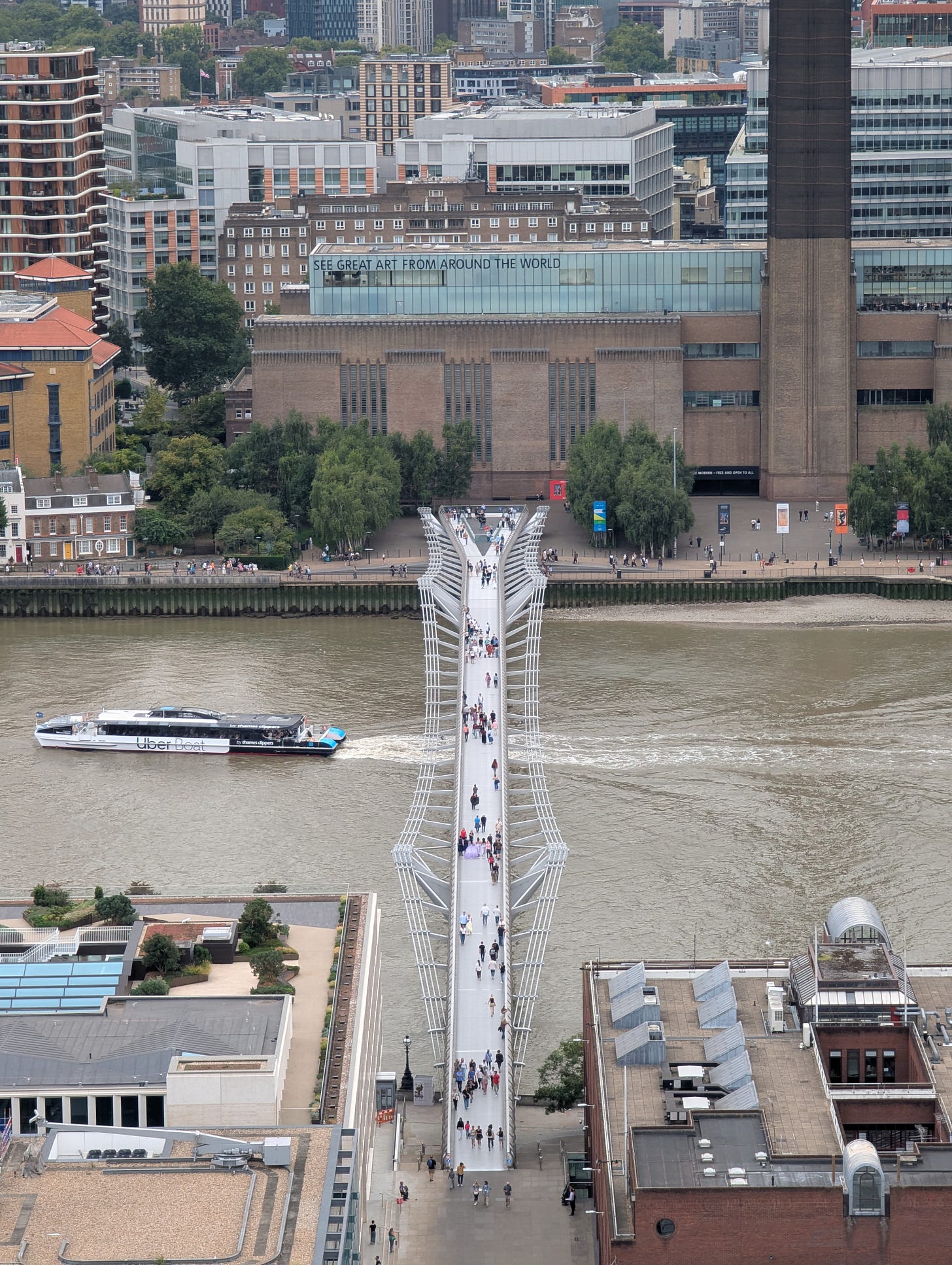

From there we went up to the Stone Gallery, the lower exterior gallery around the dome, from which you can walk around the dome and see the city. The weather was rather overcast for our visit, so we did not see it at its best. However, the views were still remarkable.

We climbed up further inside the dome, all the way to the Golden Gallery above it. Surrounded by a narrow walkway, it affords the most incredible views of the city.

Having climbed the dome, we descended to the Crypt, which contains the tombs of Nelson and Wellington. Seeing the tombs of such national heroes was incredible.

From the cathedral we made our way back to Euston Station, from which we caught our train back to Stoke. Unfortunately, our train was unexpectedly stopped at Rugby, so we had to buy new tickets online and make a dash for another train, which was just about to leave the station.

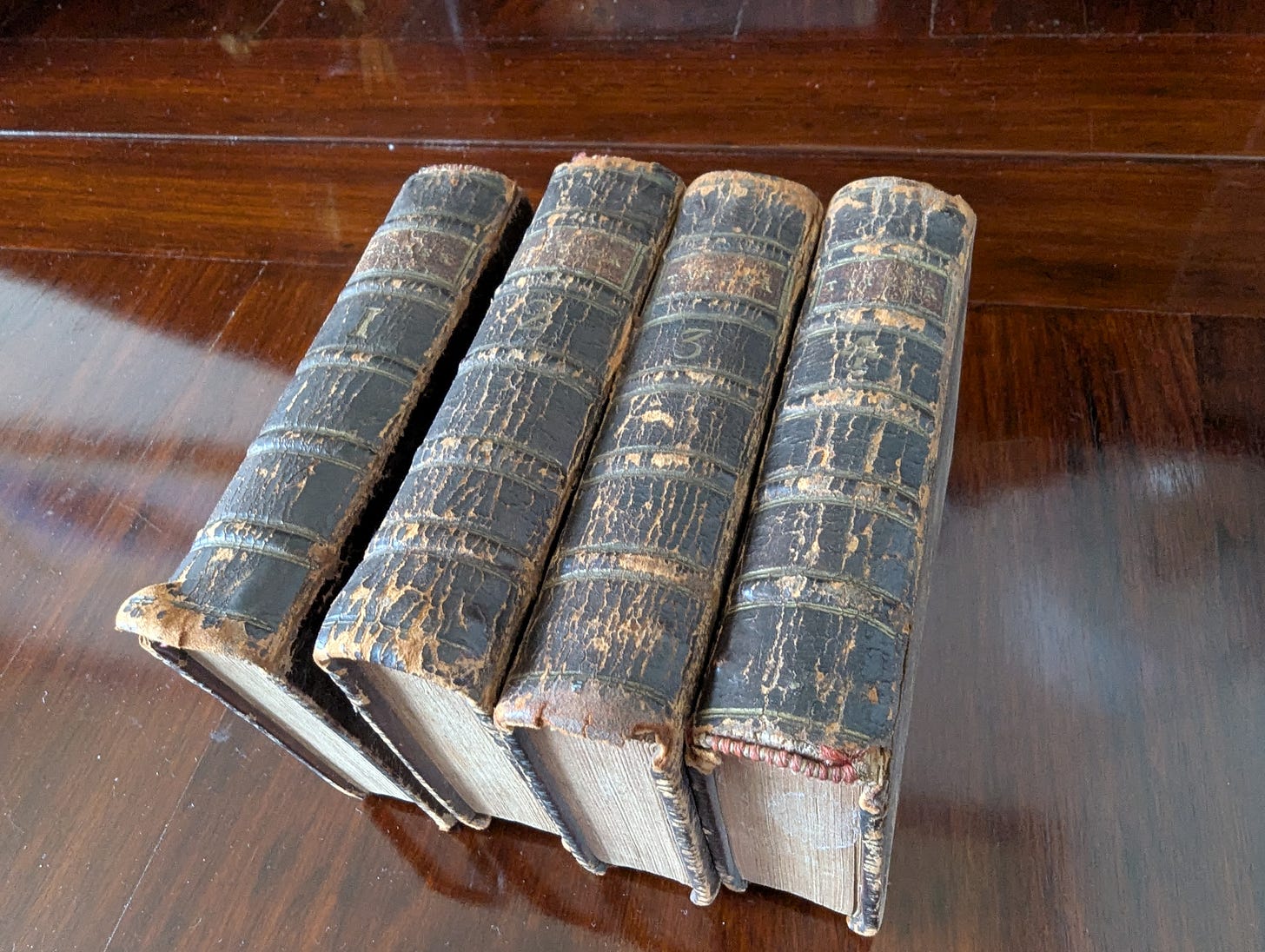

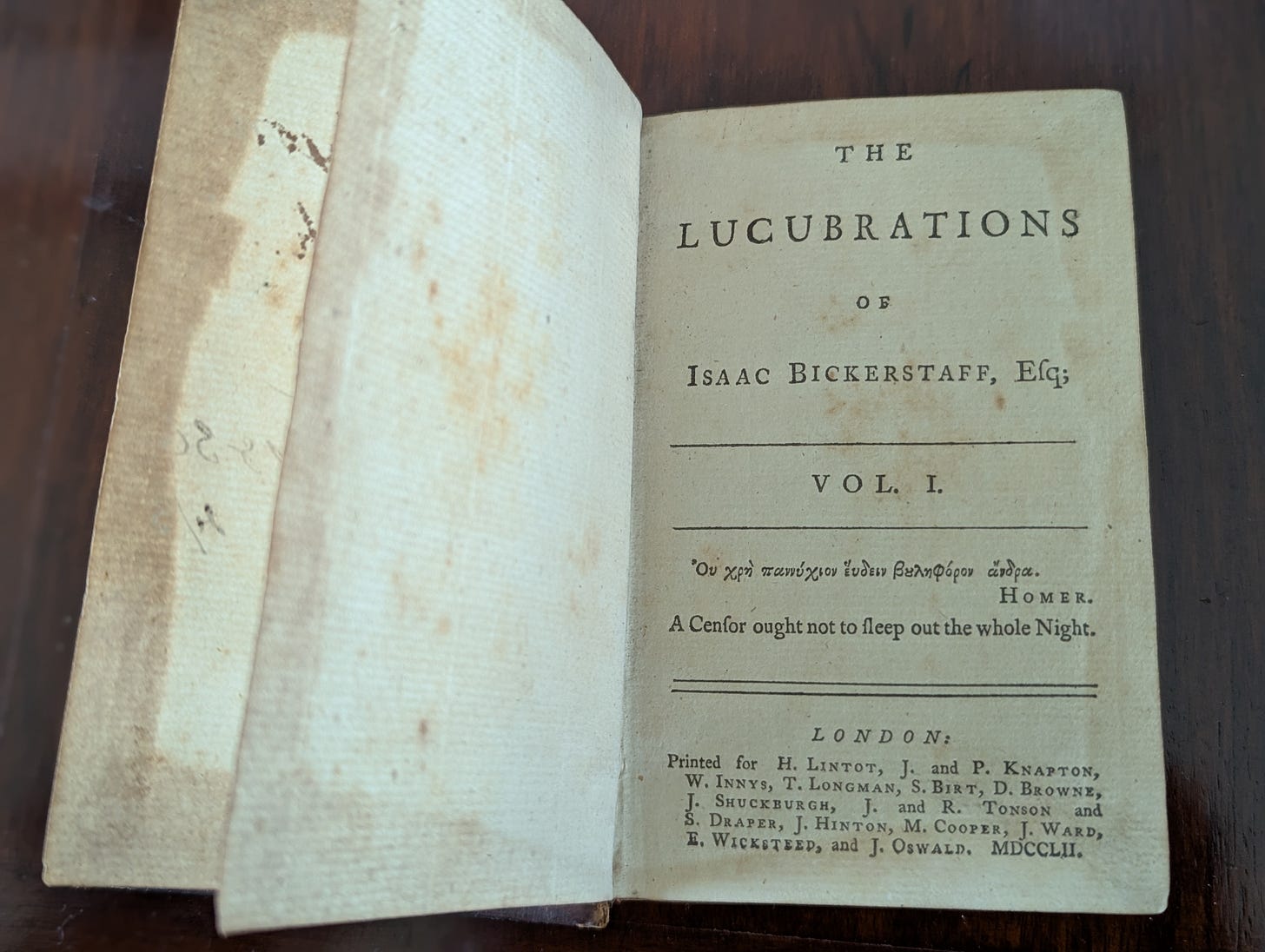

Back in Stoke, we enjoyed another more routine week. On Tuesday, after doing a little more foraging, we walked on to a local antique store. I found a 1752 edition of The Lucubrations of Isaac Bickerstaff, Esq., four volumes for only £8, a small fraction of what they would cost anywhere else. Susannah snapped them up.

Having gotten a taste for antiquing again, Susannah and I revisited Dagfields Crafts and Antiques Centre the next day, the largest centre of its kind in the region. We had a successful trip, especially on the book front.

On Saturday morning, we were treated to a visit from the wonderful Tim Vasby-Burnie, termed the ‘Top Vicar’ by The Rest is History community, and the chief organizer of the Psalm Roars.

We went out to Trentham Gardens, where, reaching the end of the lake, we climbed up to the statue on the hill, enjoying the views out over the estate.

Rather than returning directly to the path around the lake, we explored the woods a little further, as we have only been there a couple of times.

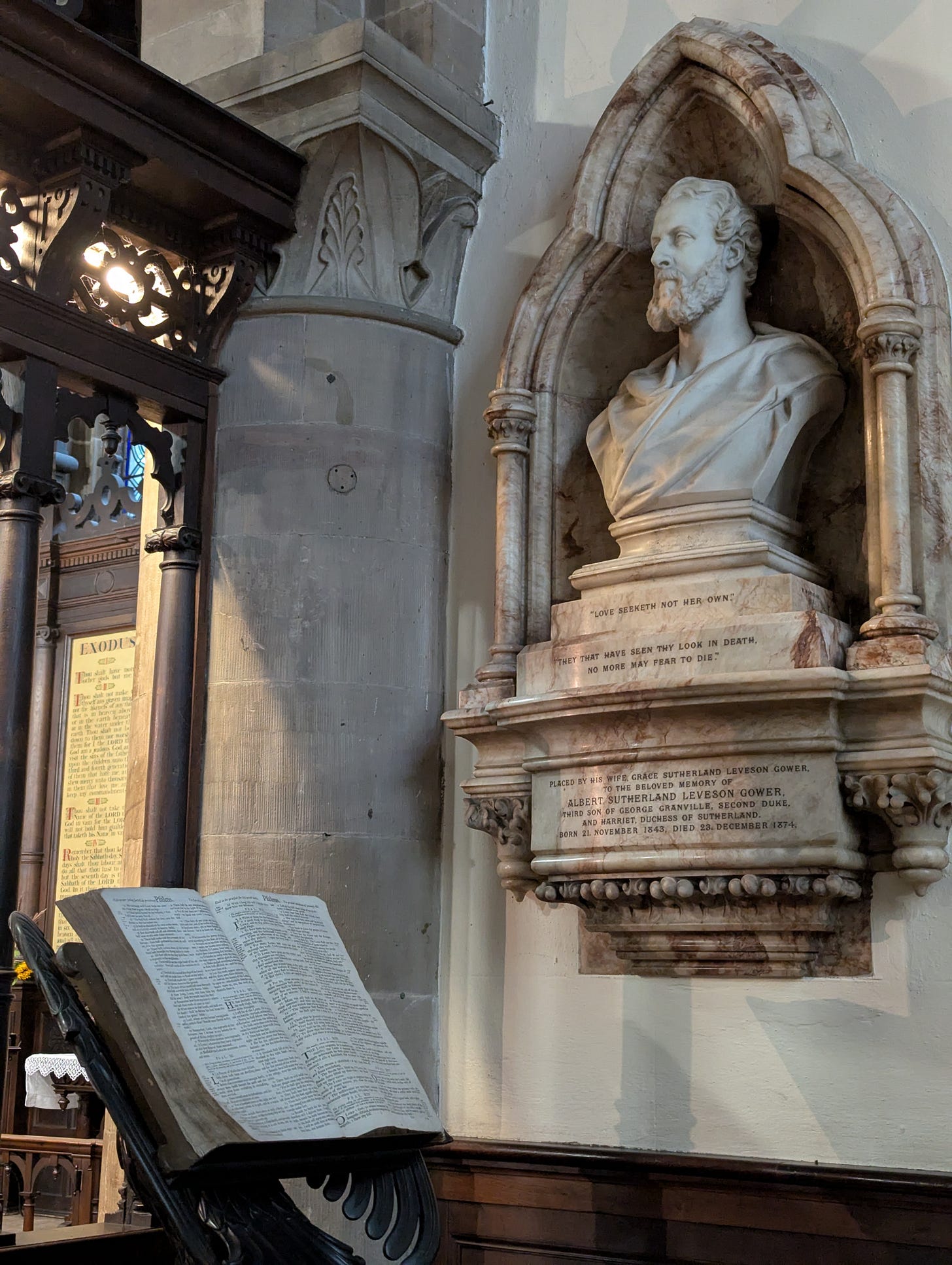

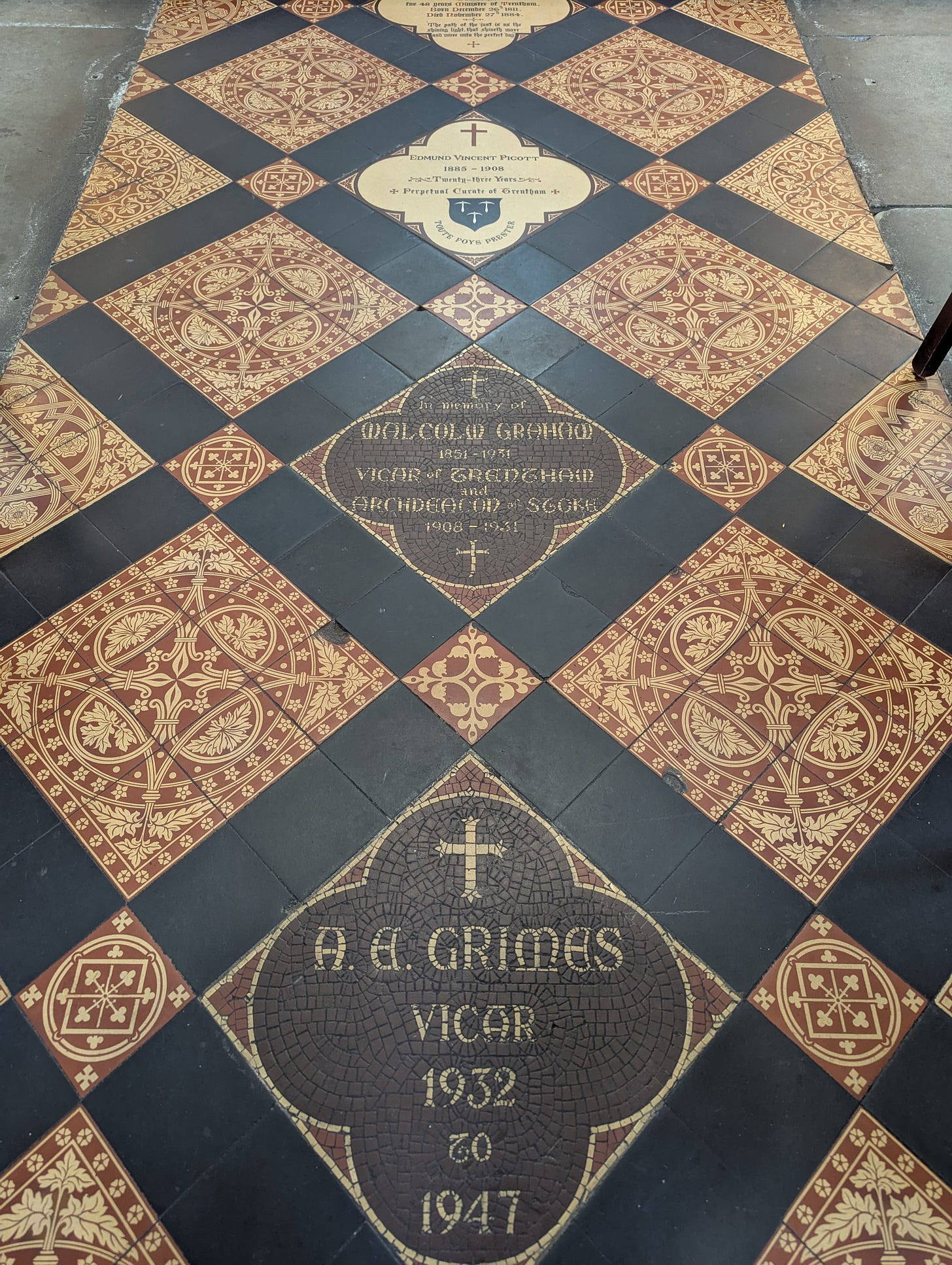

After having walked back to the top of the lake, Susannah left us to go home and return to work, while Tim and I went inside Trentham Parish Church, which was accessible to visitors and had informational displays on its history for Heritage Open Days. We bumped into the rector, whom Tim knew.

The church has a long and fascinating history, being built on the site of a nunnery founded by Saint Werburgh, an Anglo-Saxon princess, in 680. In 1100, an Augustinian priory was founded on the site. The church was on pilgrim routes to Canterbury and Chester.

After the Dissolution of the Monasteries during the reign of King Henry VIII, the priory and its lands passed into the possession of the Leveson family. In 1633, the Priory was demolished to make room for an Elizabethan mansion and walled garden, but the church was restored.

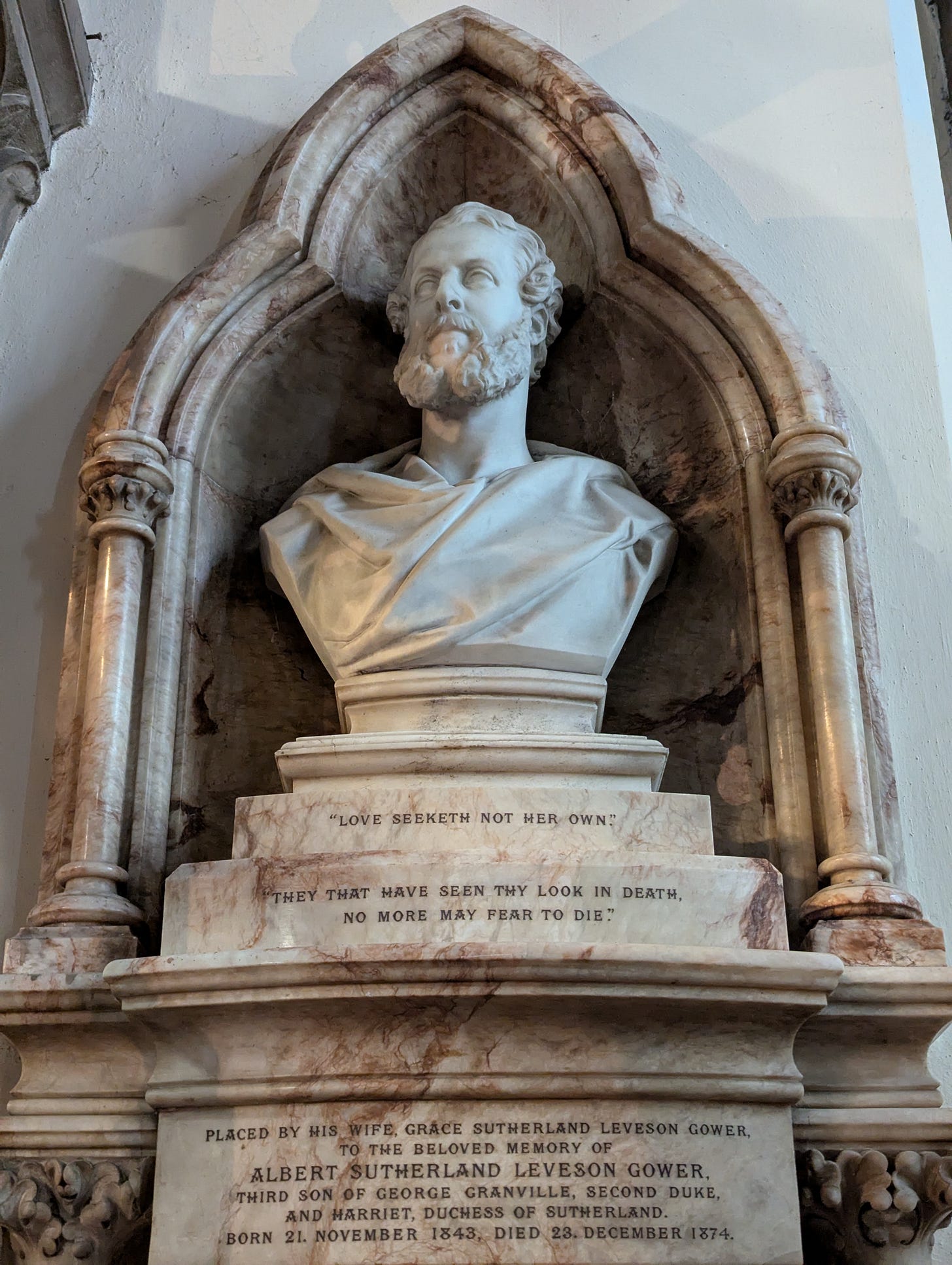

The church, which had fallen into disrepair, was extensively rebuilt by the second Duke of Sutherland in the 1840s. It was both the parish church and a private chapel, being adjacent to the palatial Trentham Hall. Harriet, the Dowager Duchess of Sutherland, has an imposing monument in the family chapel in the church.

Leaving the church, we wandered around the gardens a little more. There had been a brief downpour while we were in the church, but it blew over and the sun came out again.

I was surprised to discover that, beneath a bridge across the river, were the footings of the second oldest cast iron bridge in the world, from 1794, designed by Thomas Farnolls Pritchard for the Earl Gower.

After looking at some of the roses, we made our way to Middleport Pottery, which, in addition to being free to visit for Heritage Open Days, was hosting a market.

Middleport Pottery is very familiar to me, but Tim had not visited it before. With the Trent and Mersey Canal behind it, Middleport Pottery is a window onto Stoke’s past. Restored by the Prince’s Regeneration Trust in the early 2010s, it is now a tourist destination, and has featured in Peaky Blinders and was the location for four series of The Great Pottery Throw Down. Burleigh Pottery is produced and sold at the site.

First built in 1888, pottery continues to be produced at Middleport using the same methods as were used at the time of its founding. It has a working Boulton steam engine, a bath house which once served the workers, and one surviving bottle kiln. The site now houses several independent retailers and a wonderful café, where Tim and I enjoyed some oatcakes before he left.

I went home and joined Susannah, who was foraging in the park. We picked lots of crabapples. Susannah had made an experimental yet successful batch of apple butter with some of our earlier crop.

A former elder in our church had accidentally discovered a community orchard in their area of Newcastle-under-Lyme while walking his dog and had told my parents about it. On Monday afternoon, while my father had an appointment, my mother took us over to the orchard (dropping off my bicycle for repairs along the way), down a lane and then across some unpromising grass path.

My expectations of the orchard were not particularly high, but we were astonished by what we found. Surrounded by a basket willow hedge with woven doorways, were many different apple trees of unusual varieties, with several other fruits—cherries, different species of quinces, medlars, figs, damsons, etc.

Each tree had a metal tag identifying it. The apples included Brownlee’s Russets, Dumelow’s Seedlings, Pitmastons, Blenheim Oranges, Ashmead’s Kernels, Keswick Codlins, and Egremont Russets. All were free to pick and many of the trees were heavily laden with fruit. Having so many different varieties of apples and other fruits, one could harvest things in the orchard from June until early December. It was magical and left us feeling immensely grateful for the thoughtfulness, skill, and generosity of those who had planted and cultivated it.

We dropped Susannah back home, while my mother and I went to pick up my father. It was fortunate that I was with her, as the entrance to the road where the centre my dad was at was closed and we had to take an incredibly circuitous route to access it.

My mother and I visited a nearby site which was open for visitors. Formerly a flint mill, with one thick rectangular and one narrow bottle kiln, some developers are considering regenerating it. The building is quite derelict and, although much of it looks to be structurally sound, the developers have a challenging task ahead of them. However, I am delighted that they are taking it on. So much local heritage is being lost.

We have been joined by a new housemate over the past week. Marquis, who looked after our house when we were away in the US, is a student who attends our church. He returned from a month with family in Zambia and moved in on Monday. We have enjoyed having his company in the house, especially doing morning prayer all together at the start of the day.

On Wednesday evening, Susannah and I went around to my parents for a meal. My father often struggles to speak and to gather his thoughts with his advancing Parkinson’s Disease. On Wednesday, however, he was in good form, and, after the meal, we talked at length about my grandparents and great-grandparents. There were some remarkable stories. For instance, my father recalled meeting up with his brother’s penfriend and her family in the Black Forest. Her father recognized my grandfather, but could not initially figure out from where. He finally figured out that he had been interrogated by him after the war!

This morning, we visited the Trentham Makers’ Market and Susannah also purchased a wide selection of pots, jars, and devices for her jam-making. Since returning to the UK this time, she has been on a maritime crafting kick. Her office is filled with knotting projects, sailcloth bags, and other such things. Her foraging and jam-making kick have further added to the general sense of eccentric fanaticism in the Roberts household.

The Fall Without St Paul

In Romans 5:12-19, the Apostle Paul writes of the redemptive work of Christ:

Therefore, just as sin came into the world through one man, and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all sinned—for sin indeed was in the world before the law was given, but sin is not counted where there is no law. Yet death reigned from Adam to Moses, even over those whose sinning was not like the transgression of Adam, who was a type of the one who was to come.

But the free gift is not like the trespass. For if many died through one man’s trespass, much more have the grace of God and the free gift by the grace of that one man Jesus Christ abounded for many. And the free gift is not like the result of that one man’s sin. For the judgment following one trespass brought condemnation, but the free gift following many trespasses brought justification. For if, because of one man’s trespass, death reigned through that one man, much more will those who receive the abundance of grace and the free gift of righteousness reign in life through the one man Jesus Christ.

Therefore, as one trespass led to condemnation for all men, so one act of righteousness leads to justification and life for all men. For as by the one man’s disobedience the many were made sinners, so by the one man’s obedience the many will be made righteous.

While focused upon the once-for-all work of Christ, within this and texts like 1 Corinthians 15:21-22, the sin of Adam in the garden is presented as an event of decisive and definitive significance for the entire human race.

These texts have provided the chief basis for the doctrine of the Fall in Christian theology. While humanity was created upright, enjoying fellowship with God and the continuing gift of life, mankind sinned in Adam and ‘fell’ from that state. We are all removed from God’s special presence, do not enjoy the same preservation in life, are subject to futility, pain, and toil, and will return to the dust in death. Besides this, our nature, as we inherit it from Adam is corrupt and ‘fallen’, inclined towards evil. Adam’s sin is also typically understood to have introduced a broader disorder and corruption into the world, Adam’s sin and the judgment upon it admitting the powers of Sin and Death, under which the whole creation labours in bondage (Romans 8:20-21).

All human beings are implicated in Adam’s sin; we all share in his alienation from God, in the death he brought, and the guilt of his sin belongs to humanity more generally, not merely Adam as an individual. Every person, even before they sin personally, is born in sin, alienated from God, with a nature inclined to sin, and sharing in humanity’s fall from innocence in Adam.

The doctrine of original sin, and of the Fall more generally, is a prominent and important one within Christian theology. Original sin became highly load-bearing, especially in Western theology, as Augustine of Hippo and others used it to address Pelagianism and connected it to such things as the practice of infant baptism. The doctrine has also typically played a critical role in theodicy, accounting for the origin of evil within a good creation. The prominence of the Fall in Western theology became even more pronounced with the thoroughgoing Augustinianism of the Protestant Reformation, with John Calvin and other Reformers foregrounding ‘total’ depravity in their theologies, the corruption of all human faculties and actions by sin, no part of our nature being immune to its damage. The Reformation’s radical Augustinianism was perhaps most evident in its teaching concerning the unfreedom of the fallen will.

Original sin and the Fall more generally have preoccupied the Western Christian imagination, a fact evidenced in such things as the popularity of the theme in Western art.

However, reading the Old Testament, one could reasonably wonder whether the Fall is given the same significance within it. Beyond the record of the original event and apart from a small handful of texts, some of more debatable import (e.g. Psalm 51:5; Ecclesiastes 7:29; Hosea 6:7), it might seem that it does not make much of an appearance.

It might also be illuminating to consider the ways that the Fall has been handled in other traditions, perhaps especially among Jews and Eastern Orthodox Christians, who, while following many of the same texts, have ended up in different places. The Fall is addressed in a first-century apocryphal Jewish text like 2 Esdras:

And you laid upon him one commandment of yours; but he transgressed it, and immediately you appointed death for him and for his descendants. From him there sprang nations and tribes, peoples and clans without number. 2 Esdras 3:7 (NRSV)

O Adam, what have you done? For though it was you who sinned, the fall was not yours alone, but ours also who are your descendants. 2 Esdras 7:48 (NRSV)

Yet, beyond a few such atypical texts, the doctrine and event of the Fall have not been given the same profile in Jewish theology and readings of Scripture.

The differences between Western and Eastern Orthodox accounts of the Fall are not so pronounced, but still noticeable and noteworthy. In consequence of the influence of Augustinian theology in the West and the greater formative influence of debates about various perceived iterations of Pelagianism, the doctrine tends to be more central in theological frameworks in the West. Further, as forensic categories of thought generally have a lesser, and participatory categories a greater, salience in Orthodox theology, the questions of guilt that shaped the West’s account and use of the doctrine of original sin were less influential.

Such differences and divergences are worthy of consideration, not least because they can help us to identify the more specific forces, figures, debates, ideas, and sources that have shaped our theologies. In particular, the marginality of a doctrine of the Fall in much Jewish thought raises similar questions to those raised by the seeming absence of a strong account of the Fall in the Old Testament. Divergences from Eastern Orthodox Christians might raise different ones. For instance, how might our account of man’s plight differ had Augustine been less influential in the West? Or if death rather than guilt were the more controlling concept? Or if a Pauline theological framework, idiom, and set of concerns were less dominant and, say, Johannine ones more so?

In my theological reflection, I will often mentally bracket certain parts of Scripture, in order better to consider the distinct voices and concerns of other parts, or perhaps, by such temporary imaginative exclusion, better to perceive the contribution made by specific texts and authors.

Before considering the question of the seemingly low profile of a doctrine of the Fall in the Old Testament, we should probably begin by noting the fact that, were one to remove the epistles more generally or just the Pauline epistles more particularly (especially Romans and 1 Corinthians especially) from consideration, we might not find so pronounced doctrine of the Fall in the New Testament either—at least not those aspects that tend to be accented in typical doctrines. Indeed, where the Fall is alluded to outside of the Pauline Epistles in the New Testament, it is part of the devil as the antagonist—as liar, deceiver, murderer, accuser, and tyrant—that might be most foregrounded.

Since therefore the children share in flesh and blood, he himself likewise partook of the same things, that through death he might destroy the one who has the power of death, that is, the devil, and deliver all those who through fear of death were subject to lifelong slavery. Hebrews 2:14-15

Whoever makes a practice of sinning is of the devil, for the devil has been sinning from the beginning. The reason the Son of God appeared was to destroy the works of the devil. 1 John 3:8

And the great dragon was thrown down, that ancient serpent, who is called the devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world—he was thrown down to the earth, and his angels were thrown down with him. Revelation 12:9

In places like John 8 and 1 John 3, we also see the way the themes of opposing seed—the seed of the woman and the seed of the serpent—are connected to this emphasis upon the part of the serpent. The absence of the figure of the serpent or Satan in Romans 5 or 1 Corinthians 15 (although see 2 Corinthians 11:2-3) might result in this dimension of the Fall narrative being underplayed in Western theology, for which these two Pauline texts have been definitive.

As noted above, Paul’s account of Adam’s sin in Romans 5 and 1 Corinthians 15 chiefly functions as the foil for his account of Christ’s redemption: Christ’s act, like Adam’s sin, is a decisive act with consequences for all associated with him. It could be noted that these are not the only texts of such a character in Paul. One might argue that Adam is the implicit foil of Philippians 2:3-11, Christ’s obedience to the point of death on the cross being contrasted with Adam’s attempt to grasp equality with God (verse 6; cf. Genesis 3:5). In that passage, Christ is the paradigm of faithful humanity and his self-giving death the model for all to follow (which Paul imitates in 3:3-11, charging the Philippians to imitate him in 3:17). Viewed in terms of such a text, it is the Fall as the establishment of a participatory pattern of behaviour through a decisive act of rebellion, answered by the establishment of a participatory pattern of blessed faithfulness through a decisive act of obedience, with which it is placed in sharpest relief (we might also consider whether such a reading of Philippians 2 could illuminate neglected facets of Romans 5).

Elsewhere in the Pauline corpus, the Fall is treated in a way that, rather than focusing upon Adam as the representative head of all human beings, differentiates between the parts played by Adam and Eve within it, and the consequences faced by men and women respectively. In Paul’s treatment in 1 Timothy 2, he argues that Adam was not deceived, while Eve was, then alludes to the judgment upon the woman in Genesis 3, as he teaches that Christian women will be ‘saved through childbearing’ (verse 15), likely a reference to the blessing of women in this and perhaps also their participation in the greater redemptive historical ‘childbearing’. In the context, Eve’s deception is also related to Adam’s negligence in his office as guardian of the garden (and implicitly of his wife). This gives far more significance to the particular details of the narrative than typical accounts tend to. In 2 Corinthians 11:2-3, the Fall is presented as an assault upon the Bride. For Paul, such dimensions of the meaning of the Fall are not occluded by his emphasis elsewhere upon the decisive impact of Adam’s sin upon all humanity.

Outside of the epistolatory material of the New Testament, themes from Eden, the Fall, and its aftermath might be felt in the background of accounts such as the temptation of Jesus in the wilderness, images such as the crown of thorns or the ‘brood of vipers’ (seed of the serpent), parables such as the Parable of the Wheat and the Tares, episodes such as the Massacre of the Innocents (Herod playing the role of the satanic antagonist who seeks to kill the Seed of the woman), Jesus’s description of living water proceeding from him and of his flesh that one can eat and live forever, or the revelation of the risen Christ to Mary Magdalene in the garden. Such themes and motifs are subtler than the more direct teaching of the epistles. Within them we might also see the event of the Fall in a rather unfamiliar light, with lesser considered facets of it prominent while familiar facets lie more in shadow. For instance, our focus upon the universality of sin and death because of the Fall might dull our alertness to the importance of the theme of the opposition of two seeds in history in association with it, beyond its narrow application to Christ.

We should note that Paul’s treatment of the Fall in the epistles is not independent of the Old Testament witness. Quite the opposite. Paul presents his teaching as reflection upon the Old Testament narrative. One of the benefits of bracketing the teaching of the New Testament—and the epistles in particular—is that we can revisit the Old Testament and see whether closer attention reveals some of the things that Paul saw in it. Without such attention, we can fall into the error of treating Paul’s teaching as if it were just direct independent revelation, rather than the inspired commentary and argumentation that it is. Truly to understand Paul, we need to be able to articulate—and emulate—the underlying movements of sound thought, logic, interpretation, and rhetoric that produced the text of his epistles. Likewise, when we read the Old Testament attentively on its own terms, fruitful conversations between it and the New Testament treatments of it can be opened up, and those New Testament treatments will not be misunderstood as comprehensive accounts of the meaning of the events upon which they reflect.

This only being a short reflection, rather than a longer paper or a book, I will gesture at a few elements of the Fall and its meaning that I think might come into clearer view were we to consider the Old Testament witness on its own terms. I leave further reflection as a thought exercise for readers, and perhaps as a matter I might return to in the future.

First, the events of the garden in Genesis 2-3 really set the scene for the understanding of man’s standing before God. A world without sin and death, where man dwelt in a paradigmatic sanctuary, has been succeeded by a world of the curse and alienation. Adam’s sin was not merely for himself, but, in consequence of it, all his descendants are exiled from the garden. The questions underlying the entire biblical narrative are set in Genesis 1-3: how can humanity be restored to the presence of God and the human vocation fulfilled? Things such as the Tabernacle and Temple are presented as forms of return to the garden, a way having been opened up through sacrifice.

Second, understood in a narrative frame, the ‘imputation’ of Adam’s sin to his descendants depends less upon some arcane legal framework, whereby he is the individual who covenantally represents the host of humanity, and more upon the simple fact that he is our father. We inherit his standing, share his fallen nature, and live according to the pattern of rebellion that he first set.

Human beings are not created as detached individuals, but we belong to solidarities, suffering the consequences of, sharing in the responsibility of, and living according to the pattern of their actions. More particularly, Adam’s sin does not function as an abstract act of an individual, the guilt of which is attributed to other detached individuals. Rather, Adam is the father of all humanity and so we inherit his standing and his nature. Abel and Cain are born in a state of exile from the garden, cut off from the Tree of Life, from their parents’ former communion with God, and are subject to death. Adam’s failure to guard the garden from the serpent was recapitulated in his son Cain’s failure to guard the garden of his heart from Sin, the beast crouching at its door (4:6-7).

We might consider the way King Jeroboam is repeatedly presented as the one who ‘made Israel to sin’ (1 Kings 14:16; 15:26, 30, 34; 16:13, 26; 21:22; 22:52; 2 Kings 3:3; 10:29, 31; 13:2, 6, 11; 14:24; 15:9, 18, 24, 28; 23:15). Jeroboam founded the northern kingdom of Israel in a way that made idolatry integral to its identity and life and set a pattern in which his descendants consistently walked. Jeroboam’s sin had enduring consequences for his descendants and for the nation that he founded. However, these consequences cannot be separated from the pattern of sin that he established and which they followed.

Third, the Old Testament presents the sin of Adam as something that develops, intensifies, and radiates out. As I have written elsewhere:

We are prone to narrate the coming of Sin as a binary matter: once humanity was at peace and in communion with God and then it disobeyed the law concerning the tree, came under the rule of death, and was alienated from God. There is truth in this telling, but it can miss the fact that Genesis 1-11 describes a gradual and progressive intensification of the grip of Sin upon the world, the Fall of Adam only being the decisive and seminal first stage.

The sin of Adam is followed by events such as the fall of Cain, the fall of the ‘sons of God’, and the fall of mankind at Babel. Each of these sins occurs in a particular realm and context and has its own significance and consequence. In each of these sins we see a new stage in the unravelling of humanity begun by Adam’s sin. They continue the story of Adam’s Fall, but as they develop beyond it, they shouldn’t just be subsumed under it.

The sin of Adam and Eve in eating of the tree is followed by the fratricide of Cain, who leaves the presence of the Lord and founds a city in the name of his son. Cain’s line go on to form a culture based upon violence and bloodshed, typified by the vengeful Lamech (Genesis 4:16-24). The first sin of Adam and Eve, like ink dropped onto a piece of paper, spreads out, until we begin to see the institutionalization of evil in Cain and his offspring. By the time of the Flood, the entire fabric of human society, its institutions, members, practices, and ideologies were so compromised and corrupted that the thoughts and intents of men’s hearts are described as being ‘only evil continually.’

Sin comes into the world through Adam, as Paul argues in Romans 5:12. However, in the account of Genesis, while decisive in setting the path for his descendants, Adam’s sin is just the beginning of a narrative of Sin’s intensification and spread. Sin reaches a height before the Flood, leading to the cutting off of all flesh, sparing only Noah and his family. While the fundamental corruption of humanity continued (Genesis 8:21; cf. 6:5), its growth was curtailed.

This narrative of the spreading and intensification of the Sin that came into the world through Adam underlines the fact that it is not a story of innocent parties being judged on account of another’s sin. Rather, Adam set the solidarity of humanity out on the path of sin and many of his descendants continued and exacerbated his sin, suffering more intense judgments as a result. While Adam’s sin resulted in mankind being subject to death, the Flood was a more final sentence on the antediluvian humanity and humanity after the Flood had greatly shortened lifespans, humanity’s subjection to death being increased. While Adam and Eve were exiled from the garden of Eden, Cain suffered a further exile, being cut off from the wider land of Eden. At the Flood, a far more intensely rebellious humanity was cut off from the entire world.

Fourth, throughout Genesis there is an unfolding conflict between two seeds, between the righteous and the wicked. This is a complex conflict, and the righteous are clearly not without sin. Nonetheless, while all humanity is under sin, the enmity between the two seeds, the conflict between them, and the awaited victory of the seed of the woman has a prominence that tempers such themes of universal sinfulness.

This conflict also accentuates the part played by the serpent as the antagonist, which tends to be downplayed in accounts of the Fall that are developed chiefly under the influence of Romans 5 and 1 Corinthians 15. The Fall is occasioned in large part by a revolution in the heavens and God’s victory over the false gods and powers is required to reverse it.

Fifth, as I explore in detail in this post, the narrative pattern of the Fall is repeatedly recapitulated in the narratives of the Old Testament: the sons of God and the daughters of men in Genesis 6, Abram, Sarai, and Hagar in Genesis 16, Jacob and Esau in Genesis 25, the story of the golden calf in Exodus 32, and several others. The pattern of the Fall is also inverted on several occasions, most notably as women deceive tyrants. For instance, at the beginning of Exodus the serpent figure (Pharaoh) and his seed (the Egyptian soldiers) are seeking to destroy the woman and her seed (the Hebrew women, the midwives, the baby boys, and Moses most especially). The story of the Fall establishes themes that pervade the wider text of the Old Testament.

Sixth, the Fall and its consequences play out, not merely between God and humanity, but in relationships between humanity and the earth, between men and women, between different parties of humanity, between parents and children, between human beings and their own bodies, both male and female, and between human beings and their own wills, as we find ourselves partly bound by patterns of behaviour that we deplore. The judgments that follow the Fall are not merely the judgment of death or that of expulsion from God’s presence, but include the frustration of the man’s labour, the resistance of the earth to his efforts, a tension introduced in the women’s relationship with her husband, the increased difficult of her childbearing, and conflict with the serpent.

Seventh, many, reading the event of the Fall in light of Paul’s claim of death coming into the world through Adam’s sin, have imagined a radical transformation of the entire animal creation through the introduction of predation or, even more radically, the whole cosmos through the introduction of entropy. While Adam’s sin is seen to result in a disharmony between man and creation more generally, a resistance of the creation to human efforts at cultivation, and perhaps offers such thin grounds for speculation about fallen spiritual powers shaping the animal creation, Genesis says nothing about the profound transformation imagined by many.

Augustine, Aquinas, and others have suggested that animal death is not in view in Paul’s statements and that it could have existed the Fall (although we might imagine that, as the creation was made resistant to humanity’s efforts to tame it and demonic forces spread their rule within it, the processes of predation became crueller).

Eighth, in places such as the book of Leviticus, themes of flesh and its impurity and spread of corruption are prominent. Paul’s theological reflection on the ‘flesh’ in his epistles traces similar realities to the rituals of the sacrificial system.

Were we to stop bracketing Paul’s teaching in passages like Romans 5, having considered this Old Testament treatment of the Fall, my sense is that Paul’s teaching might make more sense to us. Some measure of people’s discomfort with the teaching might be relieved, especially as a fuller sense of Adam’s descendants’ natural solidarity with him, inheritance of his standing and nature, following of his pattern, and intensification of his sin were appreciated. Romans 5 could be read in the light of a much fuller account of the Fall; we would appreciate that, in that passage, Paul only touches upon certain aspects of it. Many of the more abstract theological concepts that frame the doctrine of the Fall could also be grounded in a broader narrative, leaving Adam's sin, considered in isolation, less load-bearing for explaining the human plight.

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ On the Mere Fidelity podcast, Derek, Brad, and I addressed the issue of ambition. We also had an episode on the Tabernacle, the Temple, and the Church.

❧ The Theopolis podcast series on Hebrews continues, with the following episodes: Christ’s Sacrifice Once for All (Hebrews 10:1-7) and His Enemies a Footstool for His Feet (Hebrews 10:8-14).

❧ My new series on the Song of Songs with the God’s Story Podcast continues with episodes on chapter 2 and chapter 3.

❧ Echoes of Exodus, the book I co-wrote with Andrew Wilson, was published back in 2018. However, we are delighted that it is still getting attention. The Songtime podcast interviewed me about the book and about the theme of Exodus in Scripture here.

❧ The Buffalo Reformed Podcast interviewed me on biblical typology.

❧ My Plough article ‘The Divine Rhythm of Work and Sabbath’ has been translated into German.

❧ I have recorded a couple of older reflections:

The Red Heifer and the Coherence of Numbers

Christ the Beginning

Upcoming Events

❧ Alastair has events over the next couple of weeks in Langley, BC, in Columbia, SC, in Birmingham, AL, and in Franklin, TN. Watch this space!

❧ At the end of October and beginning of November, we will be in Marseille in the South of France. During this time, he will be preaching at a church in Marseille and may also be delivering some talks in Aix.

❧ Alastair will be leading an online workshop for Theopolis in October and November on the subject of Pentecost. It is only $150 for ten hours of classes.

❧ Alastair will be speaking at L’Abri in Liss on November 21st. He will probably also be preaching that weekend in Salisbury.

❧ He will likely be preaching in Newcastle-under-Lyme—not -upon-Tyne—on November 28th.

❧ Next June, Alastair will probably be speaking in Oregon. He will then be visiting and speaking in Sydney and Perth in Australia.

❧ Much of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Alastair and Susannah

Ferrets, you say? Did they have a ferret legging contest?

https://www.outsideonline.com/adventure-travel/essays/ferret-legging-outside-classic/?scope=anon

All good.

Especially news about The Magician's Nephew!

I've always thought that plot was tailor made for film and wondered why successive film makers kept skipping it.

I look forward to the young worlds and cinematically powerful baddie!!!