№ 43: Our God Contracted to a Span

A postliberal conference, the flu, and reflections upon the infant Jesus

Alastair: This is the second Substack post in just under a fortnight, which is almost unprecedented for us. We should be posting a review of the year in another week’s time, so I am hoping that you all will not be tired of us!

I flew back to New York from my time at Davenant on Wednesday the 11th. Susannah was flying out to the UK that evening, so we had a couple of hours after my arrival back before she had to leave.

That evening, I spoke at Hephzibah House, which may have been my first time back there since our wedding reception. I spoke on the importance of embodiment in Christian faith. There was a good turnout, including several friends and acquaintances. After my talk there was a question-and-answer time, with some very thoughtful questions from the audience (one concerning the way to approach situations where museums have bodies that have not been adequately handled according to their cultures’ customs, for instance). Several people came up to me afterwards with further questions.

On Thursday morning, Derek, Andrew, Matt, and I recorded our final episode of Mere Fidelity with the full original cast. We have been podcasting together for over ten years now and, although we have thousands of listeners, I think we have always been driven primarily by how much we value our conversations together. Matt is a dear friend and, although we will remain in very frequent contact, it is sad to see the ending of a conversation that has lasted over a decade. Derek and I will return at some point next year, after a few months’ hiatus. Andrew will still be an occasional participant, but the podcast will have to be reimagined.

On Friday evening, I went to a performance of Handel’s Messiah in Central Presbyterian Church, in which one of our friends was singing. It was a superb performance, intensifying my Advent mood. The evening ended with a few Christmas carols in which we were all invited to join, during which I got a few photos.

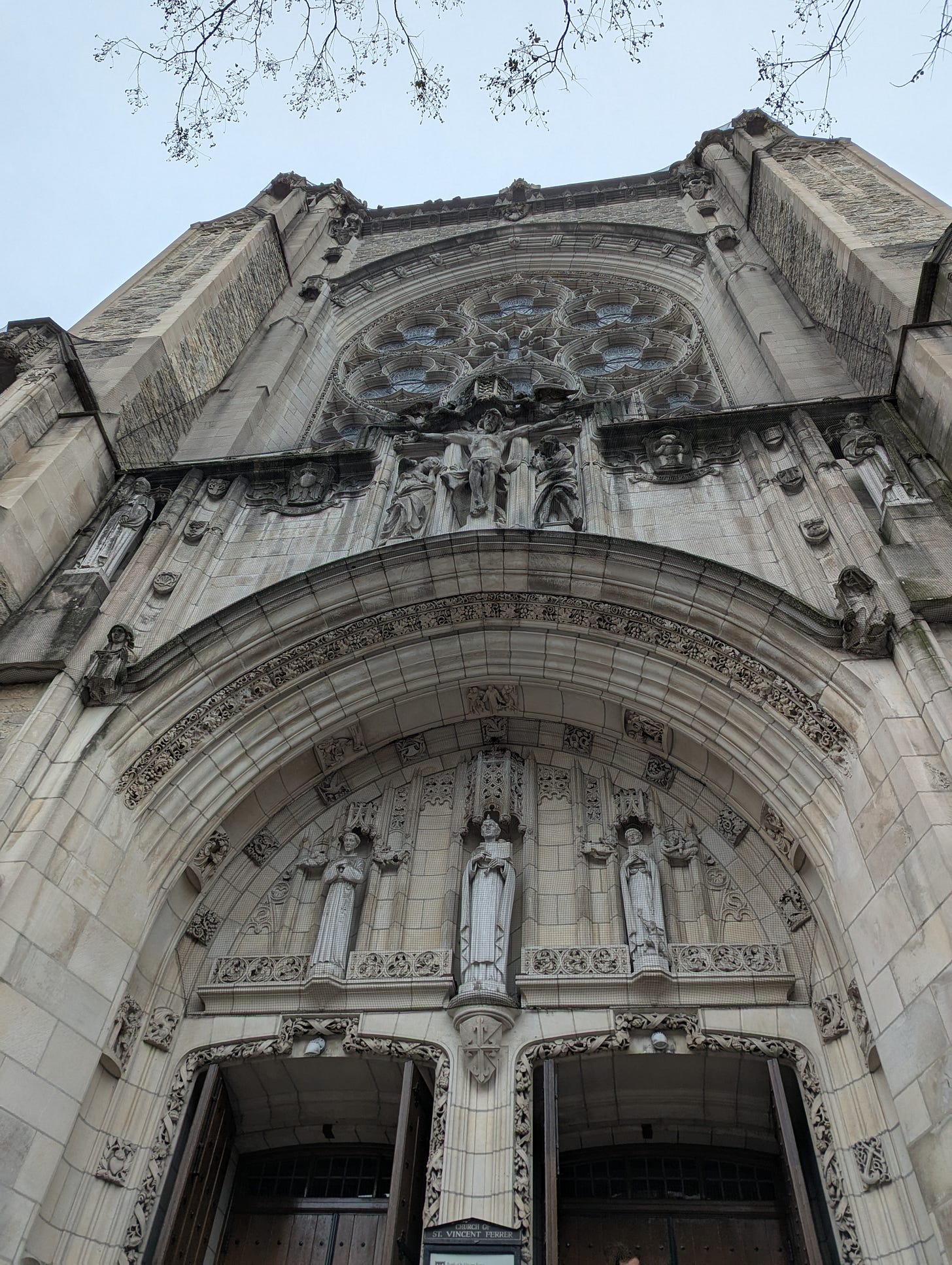

After church on Sunday, I met up with a friend in the city. He remarked to me that the skull of St. Thomas Aquinas was on display in St Vincent’s for that hour and, not wanting to miss such a fortuitous opportunity, I suggested that we visit it. After some time queueing, we were ushered forward to a rail on one side of a golden reliquary with small glass panes (another couple of people knelt on the other side), and requested to keep our time brief. Through these panes one could faintly see the skull of the saint, although it was more clearly visible from the front. There are two skulls reputed to be Thomas’s: one presumes that only one is actually his. Of course, I am now personally invested in this question. People were touching religious objects to the glass, a practice that aroused very Protestant sentiments in me. I prayed briefly to the One to whom Aquinas dedicated his brilliant mind, that I would, in my modest capacities, faithfully follow the saint’s example.

Following the visit, we went for a meal and had a fascinating—and rather mind-bending—discussion about group theory and the numerical logic of the days of creation. My friend left me with some incredibly promising lines of consideration about the days of creation that I had not formerly explored. Later that evening, I attended the Christmas party in our building and got to meet some of the other residents with my mother-in-law. I also finished knitting a scarf.

Susannah arrived back from her conference in the UK on Monday evening. I had been very eager to see her again, having been away from each other for over a week, save for a brief overlap on the Wednesday. Unfortunately, she came back with what seemed like a heavy cold, but which later turned out to be a nasty flu. She has been quarantining herself since then, although it finally seems as though she has turned the corner. The superintendent had been painting my office, and for the first few days there was still the smell of paint, but I have been sleeping there for the past week.

The rest of the week has been quiet, occupied with writing and some added chores to keep everything running while Susannah has been unwell and her mother away. We had been expecting to go upstate to spend some time with her father and stepmother, but that had to be delayed. I met up with a couple of friends during the week and did some Christmas shopping. This morning we woke up to snow, we had the final Pesher group for the Theopolis Fellows Program, and Susannah was finally up to going for a walk in the afternoon.

Susannah: Well, Alastair’s told my tale of woe, which was certainly very interesting as I was going through it but which I will not subject you to. Well, actually I will. I had a fever and a horrific cough (the cough is still here, though less, but as I am out of the time when I could be contagious I no longer feel as though it is weaponized.) There were a couple of days when the fever coyly went away in the morning but came back by evening, which was frustrating. It felt more hallucinatory than anything else; I kept having what seemed to be deep insights into important questions and then forgetting them. I did a lot of googling about what exactly it is that we feel when we feel sick: Why did my body ache? Why did I feel like all I wanted to do was watch episodes of 30 Rock? Was I being lazy?

Well it turns out that your body aches because your white blood cells, every time they grab on to a little virus guy and merc him, release a chemical which makes your muscles feel sore. There are things called cytokenes that are involved. This made me feel a lot better about the muscle soreness, because it took on the character of powder smoke over the sea after Nelson fired a broadside: it stings your eyes, but it’s evidence that the little Corsican’s fleet is being wasted. Also there is a well documented thing called “sickness behavior” which other animals do to, which is being antisocial and curling up and not wanting to do anything but watch episodes of 30 Rock, or whatever the equivalent is if you are a marmoset or whatever.

Once I convinced myself I wasn’t being lazy I happily watched episodes of 30 Rock and rested until, the last day of the fever, I got so bored that I just could not manage to not work, so I did some work and that seemed to put the kibosh on the whole thing, which lasted through a weekend and most of a week.

However what is a lot more interesting than that (though I know you were all mesmerized) was the conference that I had gone to Cambridge (the UK one) to do. The TLDR on the conference was that I and several of my cronies had determined that we wanted to re-take some key ideas related to Christian communitarianism or “postliberalism” which had been hijacked by the American “Christian nationalist” Right. We felt the need to make a strong stand against the populist and hypernationalist ideas that had been kicking around, and to speak up against the racialist and antisemitic political theology that has been gaining ground in the States, as well as against the rise of the post-Christian Right, and to promote a positive vision of a politics anchored in the transcendent but open to pluralism and protective of the goods - freedom of conscience, procedural justice - which we associate with liberalism.

Our claim is that these goods can’t actually rest on the anthropology and metaphysics that liberalism offers, and so they must in order to be preserved be grounded in better, pre-liberal philosophy. What, after all, is a human right? Where is it when it’s at home? If you’re a materialist, on what basis do you say that a law is unjust? If you’re operating from a purely naturalistic framework, what is it about humans that we should treat them any differently than viruses?

Also we wanted an excuse to gather together a collection of interesting people, and for some reason we had (months ago) decided that Advent was the time to do it. Surely, we thought, no one would have other plans, during Advent.

We held the conference in Corpus Christi College in Cambridge, which is where, in 1939, TS Eliot gave the lectures that would become The Idea of a Christian Society; that felt portentous (the good kind of portentous). The formal dinner Saturday night was in Ridley Hall’s dining room; half the people at my table knew Alastair’s work, which made me very smug.

I was on a panel responding to John Milbank; Michael Gove chaired. Other panels included Paul Kingsnorth and Tara Isabella Burton and others on “Imagination and Action: Combating the Machine;” as well as panels on geopolitics and energy, economic democracy, global capitalism and the ecological crisis, civil society, Christianity in a pluralist polity, the idea of Left Conservatism, and many other topics. One of the speakers on the second day was Tom Holland (the historian, not Spiderman.) He’s extremely personable and fun to be around.

“So let me ask you a question,” he said to my friend Tom Chacko on being introduced. “Can I deduct a dinosaur on my taxes?”

“It depends on what you’re using it for,” said Chacko gravely.

“At the moment it’s just on my desk,” said Holland. He had bought it at a local auction house right near his childhood home, when he was visiting his parents recently, for the very low reserve price, and was still riding the high of being a dinosaur owner. We did not gain clarity about the tax status of the dinosaur, but we did go on to cover many other topics, both in the tea breaks and in the Milbank/Holland/Roberts/Burton discussion at the end of our table in the restaurant dinner after the end of the conference.

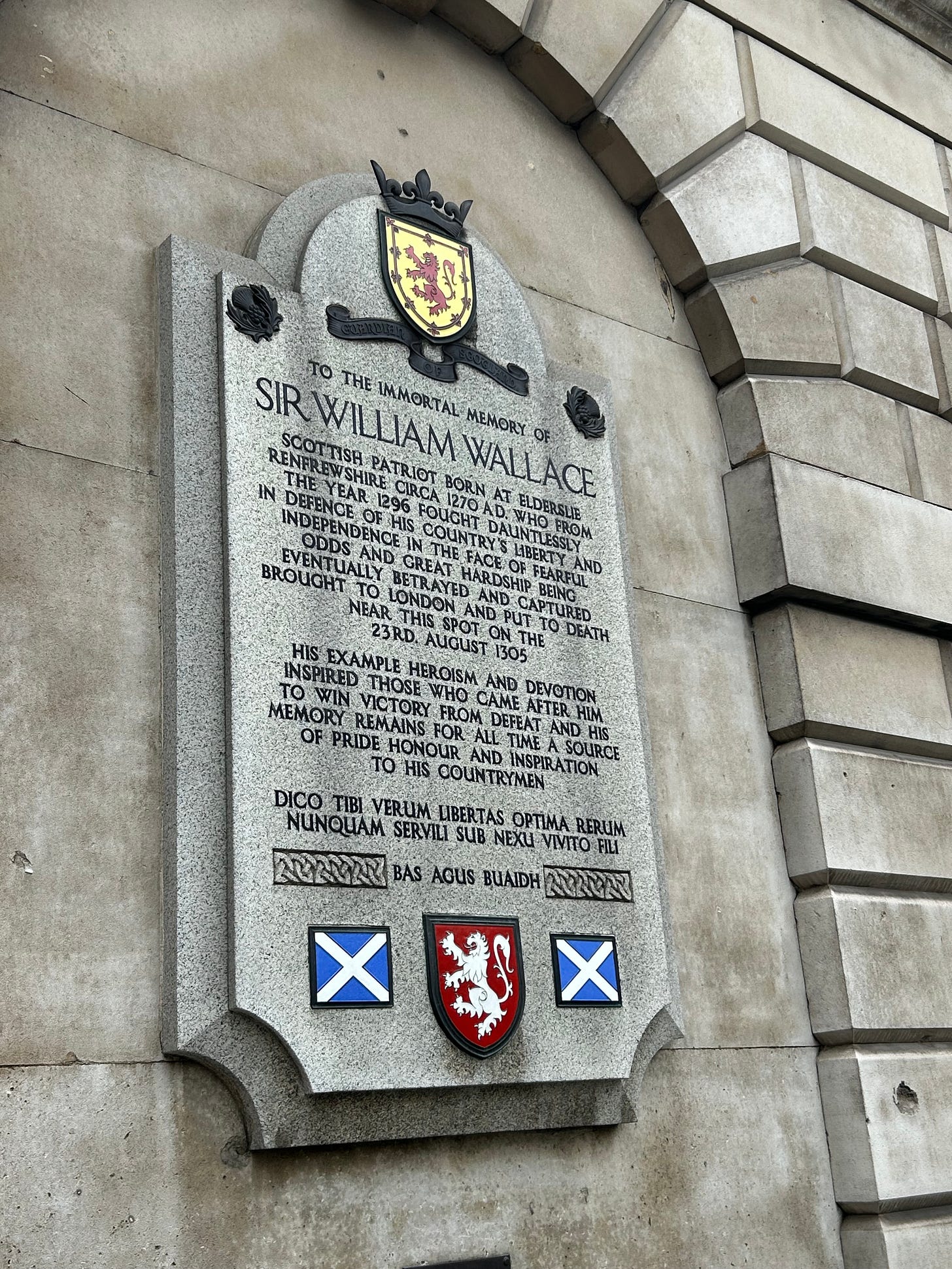

He invited Tara and me to church with him the following day, which meant that we had to wake up at a reasonable hour and take the train into Kings Cross and thence to Smithfield, where St. Bartholemew the Great is, which is the church Holland drops in on when he drops in on church. We got to the area about half an hour early, and Holland gave us a quick personalized local history tour of the area: the association I had with Smithfield was of Wat Tyler getting killed there by the then-Mayor, and his rebels being halted; it’s also, though, the location of William Wallace’s execution and other executions as well. And many other things.

Holland is not Christian, exactly (one of the things we talked about was metaethics; we got to the beginning of the conversation about materialism that starts with the direct perception of there being laws that are unjust and just, and with the reality of numbers as immaterial objects, but I was by that second day of the conference so exhausted that I just couldn’t quite go the distance; it’s a conversation that covers a lot of the ground of David Bentley Hart’s Experience of God, plus a bunch of Ed Feser, and it just takes quite a bit more stamina and less incipient fever than I had in me at the time), but he’s very Christian-friendly. He also has experienced several Marian miracles: he prayed in the Lady Chapel in St. Barts this time last year when he had just gotten a cancer diagnosis, the surgical treatment of which was going to leave him disabled; upon reexamination, the tumor was easy to snip out and he is fine; he also experienced another similar possible-miracle there. He is disconcerted by this: he was, he says, a year ago a firm atheist. Now, he is questioning his atheism. It could be a coincidence, he says, but it “seems ungrateful to Mary” to insist that it is so. (He has told this anecdote in public before so I don’t think I’m doing anything wrong in sharing it.)

He told this to Nick Cave, the singer from the Bad Seeds, who is a friend and a fellow St. Bart’s congregant, and who himself converted twenty years ago. “Nick said that I was right and it was ungrateful to Mary,” said Tom. “When I was an atheist,” he says, “I was a very Protestant atheist. So I don’t exactly know what to make of this.” It does seem to me to be a bit of trolling by God.

When we arrived at the church, post-mini-history tour, the door was opened for us by a man with a face like a gravedigger: tall, gaunt, dressed all in black, longish black/grey Snape hair, cheekbones projecting over cavernous hollows, a rocky landscape of a face. He nodded at us. Oh, I remember thinking, how nice - he must be some elderly pensioner who the church pays a bit extra to in order to be the door-keeper during services, or a sexton or something. I had a whole narrative about this in my head. But it was Nick Cave.

St. Bart’s is London’s oldest parish church, 900 years old; Holland pointed out how you can see the architecture transition from the earlier Romanesque to the Gothic; the Romanesque with its modest vaults and door and window arches, curved rather than pointed; the feel is of a cellar, but, despite the stone-damp clay smell, a cozy holy cellar where a friar might keep his barrels of wine.

The service was lovely, a sung mattins service, and Tara and I miscellaneously ran into another friend there, and then three others who had come on purpose to join us but who had independent connections to the parish, and several other friends-of-friends; NYC/London Anglo-Catholic Nerd World is, once again, a very small place. but I was by that time absolutely exhausted, and so Tara took off for the airport (she was, again randomly, on the same plane as the friend we’d met at church), Tom went off to lunch with Nick, and I fetched myself up at the Bruderhof-adjacent community in Brixton where I tend to stay when I’m in London and they’ll have me.

I’d been planning to do some Christmas shopping that afternoon or the next day, but in the event I ended up feeling very strange and sleeping for fourteen hours and waking up just in time to get to Heathrow, and then, by the time I had touched down in NYC, the Strangeness had resolved into a rather high fever, so by the time I actually made it back to the Upper West Side, the whole of the conference felt rather hallucinatory. Had Michael Gove actually chaired my panel? Had Tom Holland bought a dinosaur and experienced several Marian miracles? Was Nick Cave moonlighting as a gravedigger in Smithfield? Had Lord Maurice Glasman spoken at a panel and then spent the rest of the time cracking jokes and chain-smoking in the pub yard near the Corpus lecture hall, the yard of the pub where Watson and Crick went immediately after discovering DNA; where, upon walking in, they had said “we’ve discovered the code of Life” and asked for a pint? What was real?

For one thing, the British Interplanetary Society is apparently real and nearby the Brixton community, because I got a photo of it.

The conversation I didn’t have with Tom (the one about metaethics and math and reason, the one where you start with the fact that whatever else is true, materialism can’t possibly be true, because numbers and proportions and logical relations exist —you can use them to get to the moon and make buildings that don’t fall down and help work out the structure of DNA and so on— but can’t be pointed to in the material world; where is Eight? Or Fifty Seven? Or Half?) is one that I have a tendency to lean into in the autumn of each year, when I become very Classically Theistic and think about God as the Logos, as Reason Itself, as the One, as something like math, in fact. Reason: this is, as St Thomas says, “what men call God.” The Good, the One, the True.

This is a very salutary exercise, and it is also extremely good preparation for Advent, and then Christmas: that beginning of the year when we are reminded that the Christian claim is that the Universal Principle of Reason, Being Itself, lived and grew for nine months inside a Jewish teenager and then became a tiny sleepy newborn zonked out on colostrum in a stable in Bethlehem. The God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, with the beginnings of a nursing blister and Mary’s own antibodies beginning to beef up his naive immune system.

Christmas is the peak time of the thing I used to think of as the Good Spooky, which I now know as holiness: It’s the dark of the year and something impossible is happening, something beyond impossible: not just supernatural, more than supernatural. And we can, around the edges of our experience of the feast, sometimes perceive it: we are invited in. It’s the most familiar of Christianity’s public faces, and just because of that, when you convert, it becomes the strangest: I’ve described before how, the Christmas after the year I converted, I sang Hark, the Herald Angels Sing and even though I had sung it probably every year before that, I had never heard the lyrics before, not really: the feeling is like those dreams where there’s an extra room in your childhood house that you somehow never noticed, or maybe an entire extra wing.

Veiled in flesh the Godhead see

Hail th’incarnate deity

Pleased as Man with man to dwell

Jesus, our Emmanuel

But I will let Alastair write more about that.

God Come to Us in the Infant Christ

There is no shortage of accounts of the gods or other heavenly beings manifesting themselves in human form. Pagan mythologies are replete with accounts of gods appearing in human form and interacting, even to the point of having sexual relations, with human beings. The Bible is no exception to this pattern. At various points in Scripture, heavenly visitors appear in human form. The bodies of angelic visitors seem to have been capable of typical human bodily functions: the angels who visited Abraham and Lot in Genesis 18 and 19 were able to eat meals, for instance.

One could even imagine a situation in which the Most High God—not merely members of lower tiers of deities or angels—himself appeared in human form as such a heavenly visitor or messenger, interacting with us as one with the same appearance. Indeed, throughout the history of the Church, many have seen the pre-incarnate Christ in some of the figures described in the Old Testament.

Other myths spoke of demigods, persons with mixed ancestry—part human, part god—or of mortals who underwent apotheosis, being raised up to a divine status. Greek demigods, such as Perseus, Achilles, Heracles, and Aeneas, might come to mind here, along with figures like Cú Chulainn or Erlang Shen from other mythologies. The biblical literature includes curious accounts such as those of Enoch’s translation or Elijah’s fiery ascension, events which some suppose elevated them to the status of immortals, inspiring extensive speculation. We might also consider the cryptic account of the ‘sons of God’ who took the daughters of men in Genesis 6:1-4. There is an ancient reading of this, most famously narrated in the book of Enoch, that reads the sons of God as the heavenly Watchers, who produced the Nephilim through sexual relations with human women.

Heavenly visitors temporarily assuming human forms for some specific purpose, demigods arising from the promiscuity of lascivious or rebellious deities, or the elevation of divinely favoured mortals: all provided paradigms for understanding gods appearing in the likeness of men. Indeed, as I have noted, the biblical narrative itself—and far more so the eccentric extrabiblical traditions that developed out of it—have several instances of such events.

Considered against such a colourful backdrop, one might consider the story of the Incarnation as merely a more dramatic instance of familiar tropes. Recent decades have seen a burgeoning interest, both in academia and popular literature, in ways that occasionally psychedelic texts of Second Temple Judaism and early Christianity can complicate our categories for understanding divine, angelic, and human natures and the possibilities of their relations. Sharp boundaries between the mortal and the immortal, the heavenly and the earthly, and in some cases even the Divine and the creaturely are unsettled by beings that traverse, transgress, or are intermediate for such categories.

Scholars are not mistaken to note the way that the New Testament explores and develops such themes, connecting Jesus with various Old Testament stories of theophanic angels, heavenly messengers, God’s Spirit descending upon heroes, miraculous births, ascended prophets, along with various traditions of Wisdom or the Logos. Yet the multiplicity of such themes is part of the point. Along with the numerous human motifs—Last Adam and Second Man, Melchizedekan High Priest, Davidic Messiah, Prophet like Moses, etc., etc.—each of these tells us something about how Christ is to be understood, but none exhaust the New Testament’s account of him. The very multiplicity of the categories is provoked by the insufficiency of each one of them. Christ fulfils, yet also exceeds, all such paradigms and archetypes.

The early Church’s preoccupation with the question of the Incarnation was driven by its concern to speak truthfully about the mystery of Jesus Christ, which lies at the heart of the Christian message. The seemingly abstruse philosophical categories and distinctions produced by its often-fierce debates might seem to be indicative of a theological fastidiousness divorced from all reality. However, more than anything else, they were motivated by the importance of ordering the Church’s confession and life around the great and glorious mystery of Christmas.

In confessing their faith that God became Man in Jesus of Nazareth, the early Church was generally not articulating its convictions in societies that could not imagine gods appearing as men, but in societies with no shortage of such fancied beings. There was a menagerie of intermediate and other heavenly beings, among whom Jesus could be classed. Perhaps Jesus was an angel who appeared as a man, a human Messiah who was elevated and empowered by God, a human being temporarily possessed by the divine Spirit, a lesser divinity generated by the Supreme Being, or perhaps his humanity was an insubstantial and illusory appearance generated by God. The challenge of the Church was not to allow its confession to be compromised by adopting any of the lesser options on offer, but to assert a mystery that exceeded any myth’s imaginings.

For instance, Mary was and remained a virgin in the conception of Jesus; no sexual relation occurred between her and God. Jesus was not some hybrid of humanity and divinity, an intermediate third thing, but fully man and fully God. Nor was Jesus a human person, who was possessed, as it were, by the Christ at his baptism, or exalted to divine status at the resurrection, as teachers of Adoptionism variously taught. Christ’s human nature was not like a dispensable avatar, but truly united with his divine nature. Christ’s human nature, as the tradition has insisted, was ‘anhypostatic’—not being personal in itself—but ‘enhypostatic’—being personal by virtue of the Second Person of the Trinity taking the nature to himself. All such claims served to close off culturally live options for conceptualizing the person of Jesus, ensuring that people did not fall short of the mystery.

No one less than the Most High God himself—the Supreme Being, not some second tier deity—became man. No softening of monotheistic confession or the claims of classical theism were to be countenanced: God is not one of the petty deities of the myths, beings that, while immortal, had origins, limits, and passions. The union of God and Man in Jesus of Nazareth was personal and enduring, neither temporary nor dispensable as that of a deity with their avatar might be. The union was genuine, not merely an insubstantial appearance. It entailed no diminution of the divinity, hybridization of the divinity and humanity, or evacuation of the humanity.

The meaning of Christ’s Incarnation is to be found, not so much in the similarities between it and the other accounts and paradigms on offer in Scripture, as in the differences. Any class or category that might seek to contain Christ as one among other members is burst like a wineskin filled with new wine.

For instance, in considering Old Testament angelic or even divine visitations in human form, the bodies of such visitors neither seem to have pre-existed nor continued beyond their use for a particular visitation. They had neither human origins nor histories; there was no enduring bond with the heavenly being who appeared in their form either. The body was a temporary avatar for a limited end. A body fully suitable and prepared for the purpose could be assumed and then immediately discarded afterwards. For such visitations, the body was purely functional and dispensable.

While we might occasionally see allusions to angelic visitations in New Testament accounts of Christ, the place that the flesh of Christ occupies within the gospel accounts and the Christian theological imagination is quite distinctive. The story of the gospels is, in large measure, a story of Jesus’s body. Throughout the accounts of virgin conception, birth, Baptism, Transfiguration, Crucifixion, burial, Resurrection, and Ascension, Jesus’s body is not a dispensable appearance assumed for limited ends, but central to the narrative. Salvation is accomplished in the flesh of Jesus. The fact that the Second Person of the Trinity does not merely temporally assume human flesh, but that, even after the resurrection, he continues to share our nature is an important Christian claim, setting our account of the Incarnation apart from almost all other accounts of deities coming in human likeness or flesh.

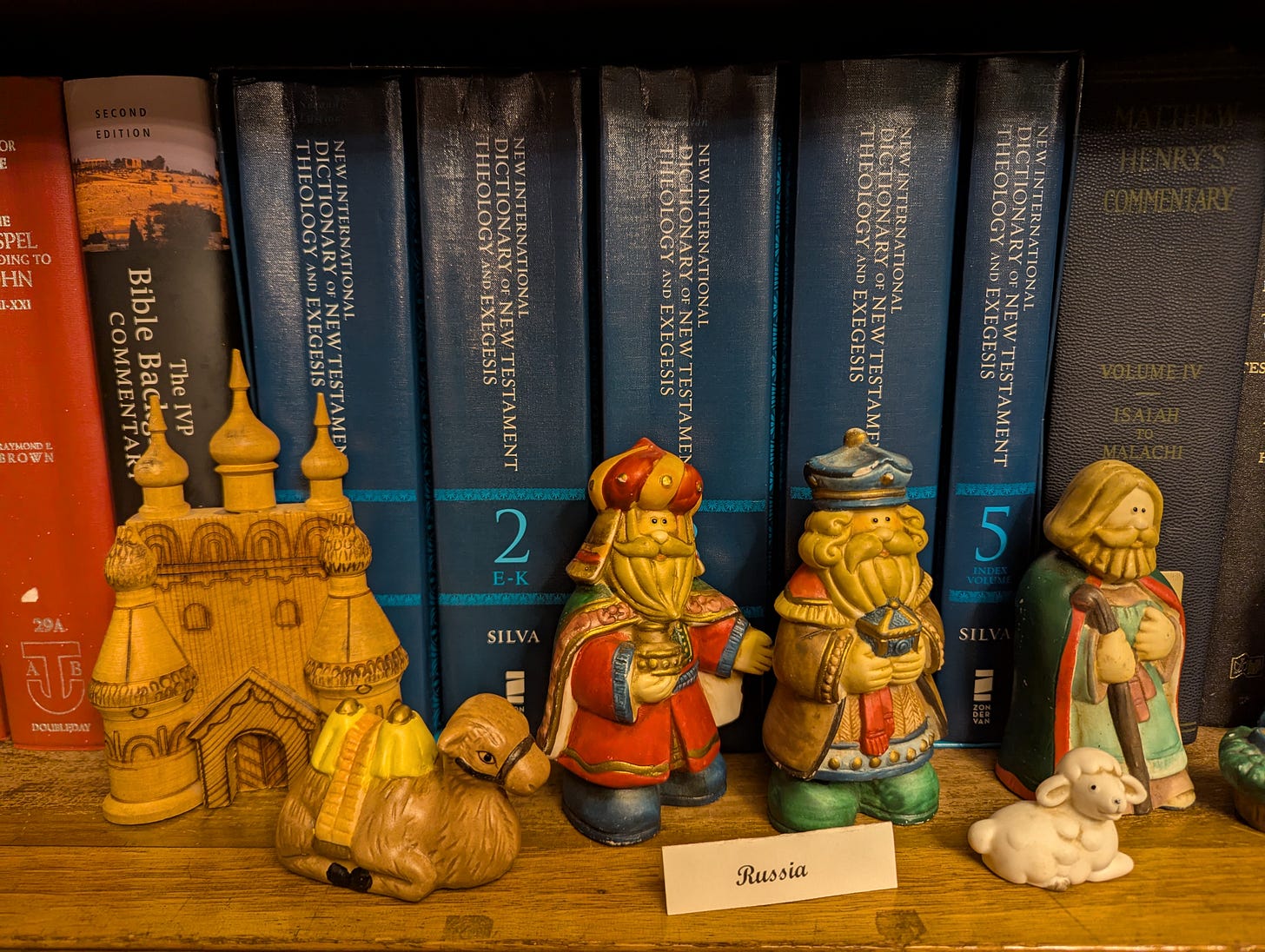

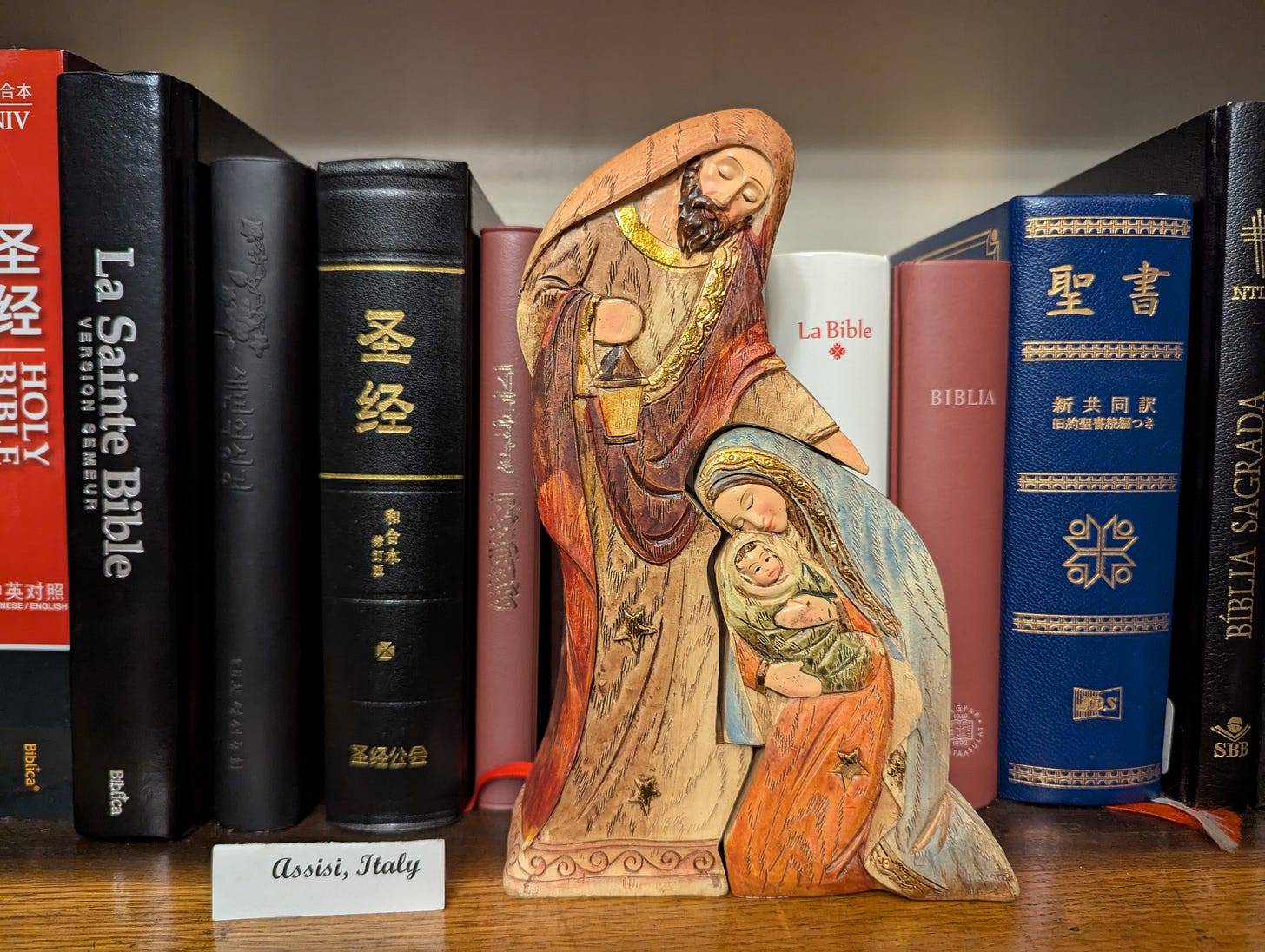

Over Christmastide, my mind is often drawn to such matters. The mystery of the Incarnation—or at least certain facets of it—is perhaps most powerfully seen in the infant Jesus. While Jesus came as a man, it matters greatly that he first came as an infant.

Prevailing accounts of human nature are commonly implicitly ordered around able-bodied adult males, who most conform to the ideal of independent rational agents. However, deeper and less considered truths about our humanity can be seen when we centre the infant, which we all were once and in which enduring truths about ourselves are disclosed. In the infant, our radical dependence upon, connection to, and entanglement with others is unavoidably seen. In the sleeping newborn gently cradled by its mother, we see our vulnerability, exposure, and openness to others. In the loving gaze of parents at their tiny child, we see the given and unchosen roots of our existence and what we represent for others.

These things do not cease to be true of adults, but our capacity to see them may gradually be impaired. As we mature, our self-expression, our choices, our agency and actions, our self-consciousness and subjectivity, our social standing and station, our thoughts and beliefs, our affections and desires, and other such things can so dominate our sense of who we are that we can become inured to the importance of our most fundamental dependent and given bodily existence. Perhaps only in the final season of our lives, where the stubborn reality of the body once again asserts itself over all these things, will we consciously reckon with this truth.

There are theological truths about the Word made flesh and God in Christ that may appear in their sharpest focus in the image of the cradled infant Jesus.

In the infant Jesus, we see that God takes our condition upon himself. He enters our humanity in its fullness. He does not merely assume a mature adult body, for the purpose of three years of teaching ministry, followed by his death and resurrection. Rather, he is conceived in the womb, born, and passes through infancy, childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. He truly becomes one of us, not merely appearing in our form, as an angel might do for a divinely appointed mission of limited duration.

Matthew’s gospel begins with a genealogy. Being born as an infant to specific parents, Jesus takes not merely generic human flesh but a particular human heritage and history to himself. He assumes a givenness that is constitutive of and common to our humanity, shouldering the burdens, the legacy, and the destiny of a lineage. Jesus is not a mere tourist in our nature, donning our likeness as we might some exotic cultural garment. He is born as the son of Abraham and the son of David.

The words of Isaiah 7:14 are recalled in the opening chapter of Matthew:

“Behold, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall call his name Immanuel” (which means, God with us). Matthew 1:23

A couple of chapters after this prophecy, in Isaiah 9:6, words famous from many services of lessons and carols are recorded: “For to us a child is born, to us a son is given; and the government shall be upon his shoulder, and his name shall be called Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace.”

These prophecies, first given to a king and people greatly unsettled by the threat of invasion during the Syro-Ephraimite War, are related to Jesus by Matthew. In the first context of the prophecy, a child to be born—some have speculated Hezekiah—would be the Lord’s assurance of the survival of his people and the Davidic dynasty and would also represent a timeline for the transformation of their situation.

In Matthew’s allusion to these prophecies, God’s entrusting of himself to his people is more evident. If the birth of a royal son to David’s house was a sign of God’s presence in Isaiah’s day, Jesus coming as an infant is much more so. Infants, in their extreme dependence, are given and entrusted to their parents. In coming as a weak and helpless infant, Jesus is ‘given’ to humanity in a far more profound way than he could be otherwise. Mary’s cradling and nursing of the God-Man is a startling image of the intimacy that is established between God and humanity in the Incarnation.

In the birth of an infant, we are made alert to time in a new way, experiencing the reality of our belonging to a generational life that extends far beyond our lifespans. The newborn infant is a sign of continuation and of newness, of the enduring of a family and its shared life and of a fundamental transition and reordering within it. Infants are creatures of time in profound and manifest ways and can, at least temporarily, open their parents’ eyes to the fact that they are too. As Neil Postman once wrote, ‘Children are the living messages we send to a time we will not see.’ In the infant, the parents see something of themselves that will endure beyond their passing, but also experience the beginning of that ‘passing’ in the dawn of a new generation. In the child, we see something of an awaited future in the present. The various people who saw the infant Jesus saw him as a symbol of hope, his infant presence a promissory assurance of his future work. In the infant Jesus, people saw a sign of the Lord’s coming to his people, keeping the promises made to their fathers. They also saw the advent of a new age and a new kingdom. In coming as an infant, Jesus both entered into time in its deeper sense and manifested God’s advent in time in ways that no other form of coming could.

The birth of a child, following the pangs of delivery, is an apocalyptic advent of joy after pain. Birth is attended by joy and entails transformation. The coming of a new child into your world transforms that world. That Jesus first comes in the darkness of the womb and the world—his birth heralded by angels to nighttime shepherds and his presence sought by wise men following a star—is noteworthy. Birth is a key scriptural metaphor, both for the climactic and apocalyptic deliverance of God awaited by his people (Isaiah 66:7-14), and for the work of Christ. As I have noted before, Luke and John both parallel Christ’s birth, or the notion of birth, with Christ’s resurrection. Christ’s coming transforms the world and brings true joy—‘good news of great joy that will be for all the people.’

In the famous ‘Christ hymn’ of Philippians 2:5-11 we read:

Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross. Therefore God has highly exalted him and bestowed on him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.

This Christmas, take some time to tarry over the import of the words ‘being made in the likeness of men’ in verse 7. The Son of God did not merely come to us as a mature adult, in control of all his faculties, but in the way that we come into being, as weak and dependent infants, knit together in our mothers’ wombs. As adults we can recoil at the prospect of such radical dependence upon others; to our pride, the prospect of ‘being a burden’ might be the most feared indignity of old age. The manner of Christ’s coming—as an infant—is a sign of his humility. Though the King of kings, he first comes to us, not in the pride, pomp, and power of a great emperor, but as a helpless child.

Finally, infants, in their radical vulnerability, dependence, weakness, and meekness, are symbols of peace. The child depends for their survival upon the establishment of a peaceful and hospitable world around them and it is in the death or killing of infants that the violence of the world is most tragically and horrifically manifest. The story of Jesus’s infancy includes accounts of brutal violence against defenceless young children, in the massacre of the Holy Innocents. However, in the baby at the heart of the story, there is a symbol of peace, of God’s life entrusted to man as a sign of a world beyond such cruelty and conflict. He is the Prince of Peace, his coming a sign of peace among men and reconciliation of God and man.

As we reflect upon the Incarnation this Christmastide, let us see within the infant Jesus God truly become man and, in the newborn Christ, God’s sign of his full identification with and presence to us, of his coming in ‘the fullness of time’ and of hope for an awaited future already present in him, of promised joy to the world, of divine humility, and of longed-for peace.

Happy Christmas!

Recent Work

Alastair:

❧ The final episode of Mere Fidelity before our hiatus has now been released: The One Thing Necessary. For over ten years, Matt Lee Anderson has been our cohost and conversation partner on Mere Fidelity and a dear friend. Derek and I plan to reform the podcast next year, but there is no way we can replace Matt, although he may visit from time to time. We will really miss him.

❧ We have reached the conclusion of the Theopolis Podcast’s Deuteronomy series. Our final episodes on the book are Deuteronomy 33-34: Final Blessings and Death of Moses and A Deuteronomy Wrap-Up and a New Series Announcement. You can see the entire series here.

❧ I reviewed Jordan Peterson’s new book, We Who Wrestle With God, in the latest issue of First Things.

Peterson’s is a Jungian approach. He sees the Bible as a distillation of the collective unconscious and its archetypes, disclosing deep truths that are of vital and perennial importance. Peterson is a man who regards myth as a matter of immense gravity, and the Bible contains the myths that, more than any others, have been the life-giving springs of Western civilization. As he argues in the preface to We Who Wrestle with God, when the West is unsettled, it is to these myths that we must return for civilizational renewal—though of course, other myths also have an important role, and Peterson often draws parallels between the Bible and stories drawn from pagan mythologies. Despite points of contact, this approach clearly contrasts with a Christian understanding, within which the Holy Scriptures are uniquely divinely inspired and authoritative.

❧ The question of whether it is appropriate to say that David raped Bathsheba frequently surfaces on social media. I reflected on the question here.

❧ In the latest episodes of the God’s Story Podcast, I discussed Zechariah 7 and Zechariah 8 with Brent Siddall.

❧ Since our last post, I have recorded the following reflections:

Advent Hermeneutics

Advent Absence

Upcoming Events

❧ Alastair will be at the Theopolis Fellows Program in Birmingham, Alabama from the 12th to the 18th January.

❧ Alastair will be speaking at New College Franklin on January 20th.

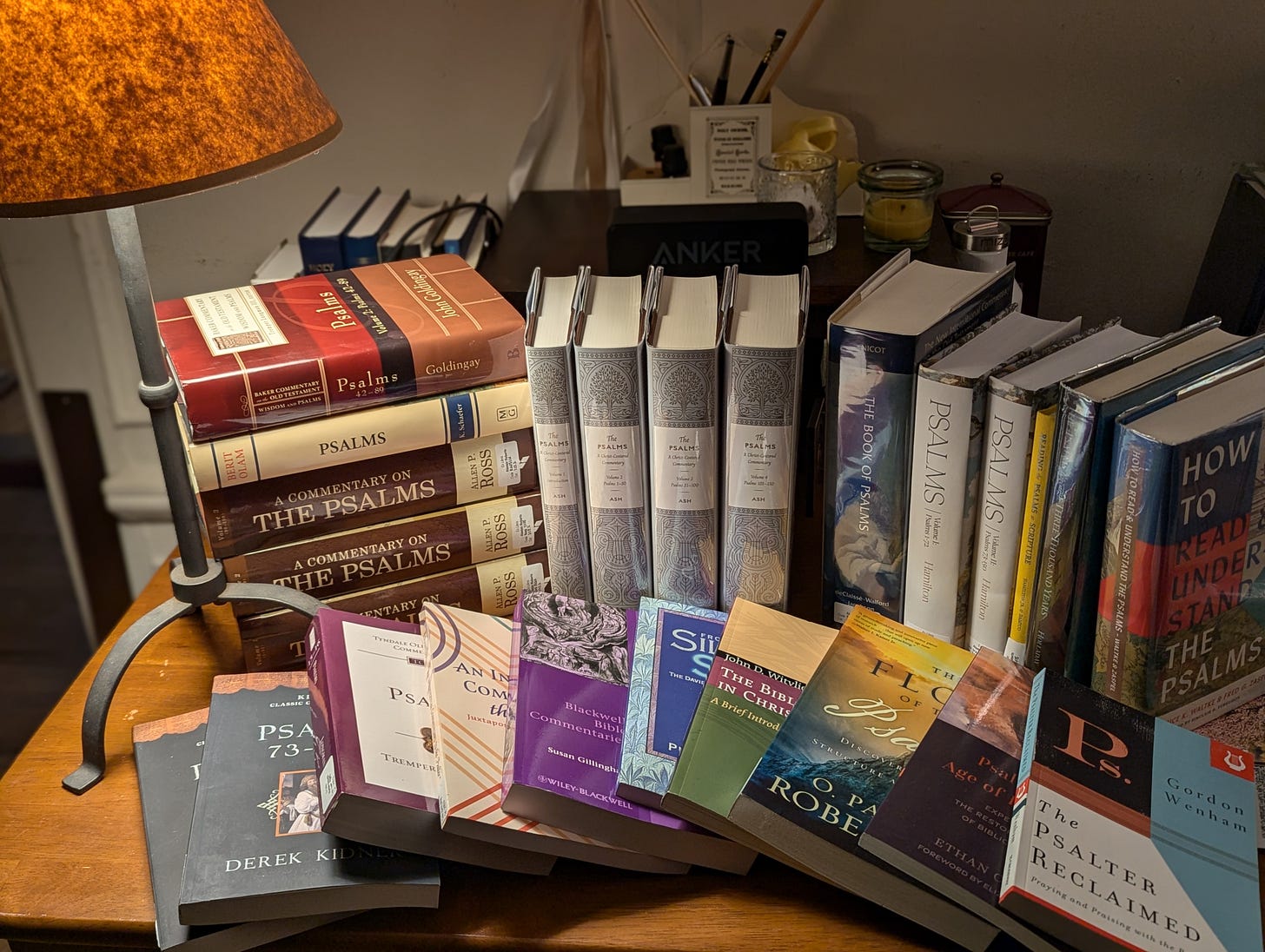

❧ Alastair’s next Davenant course, ‘The Psalms: A Bible in Miniature’, is now available for registration:

In his introduction to his lectures on the Psalms, Martin Luther described the Psalter as ‘a little Bible’, declaring that ‘in it is comprehended most beautifully and briefly everything that is in the entire Bible.’ For nearly three millennia, the psalms have been at the heart of the worship of the people of God. This course will consider the place of the Psalter within the scriptural canon and the life of the Church and its members. It will equip students to read and, more importantly, to sing with greater understanding and benefit. While deepening students’ appreciation of individual psalms, this course aims to give students a firmer theological grasp upon the role and use of the Psalter as a whole, its ordering to Christ, and the ways that it can transform our relationship to Holy Scripture more generally.

You can see the syllabus here: this will be a really deep dive into the Psalms and the literature surrounding them.

❧ Much of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Alastair and Susannah

To Alastair and Susannah: thanks for sending your detailed writings now for some time. I am not any where near on the academic or literary level that you both express so fluently each time but have found of real interest. Most impressed w/ the stunning photography and detail of observations and random buauty and humour in the pictures. Thanks so much Carol

Okay, this is the content I signed up for. Now I'll never be able to be sick again without thinking of HMS Victory's 42 pounders.

This postliberal thing has really turned into our chew toy, hasn't it? And for good reason. The inadequacy of bald liberalism seems evident by now, to the observant. But why do we say it still has good in it that we want to preserve, if at root it cannot satisfy? That's harder to answer. Perhaps it's true that the liberalism we have today was sprinkled with enough Christian salt to make it a decent framework for a while, as God prepares his people for a better move.

It seems to me that the natcons are right with us on making that correct initial observation; liberalism cannot by itself satisfy. But then it seems to me their answer to the problem is worse than just living with liberalism. Their answer is usually pure, unadulterated atavism, which is the opposite of a biblical life view, which is radically future-oriented.

I'm right with the natcons in the belief that political units have got to be shepherded in history so that they conform to the kingdom. I'm right against them in the belief that you can slap a Jesus bumper sticker onto whatever national constitution, and that will do the trick.

The Swiss have many admirable qualities that the Christian west could emulate, but I don't think that simply banning minarets, as they've done, is the answer. To me that reeks of aestheticism rather than principled establishment. Yet: the Swiss have a communal culture which Americans, for example, would benefit from studying. Both Americans and Swiss have a lot of guns, which any nation needs to defend itself; yet the Swiss have much fewer murders, and a healthy and respectful gun culture, compared with the US.

The difference? I don't think it's better rules & regulations, as a natcon might say. I think it's self-government: the ultimate liberal government, without which none of the other governments work.