Dear friends,

Alastair: When we first ventured forth on this Substack expedition, we expected to post once every fortnight. It has rather been longer than that since our last missive, in large part because the last few weeks have been so eventful for us. This makes it difficult to compress an account of all of its happenings into a single post, a challenge that only grew as we delayed writing it due to other pressures!

We thought that we would devote most of this post to pictures from the last few weeks, interspersed with notes.

Happenings and Doings

Neither of us had visited the Bruderhof community at Darvell in East Sussex before and did so for the first time about three weeks ago. It was a very meaningful visit for us and we were shown great kindness. We experienced a notable sense of the presence of God in our lives during our visit there; it has with that one visit become a special place for us.

My father’s seventieth birthday was on the 4th and my brother Jonathan and his family visited from Hamburg to celebrate it. My brother Peter and his wife, Fernanda, also joined us for a few days. It was my first time seeing Jonathan and his family in three years and Susannah’s first time meeting them. She especially enjoyed getting to know her new niece and nephew!

Celebrating my father’s seventieth birthday has reminded me once again of how immense of a blessing and influence he has been—and continues to be—in my life. No one who knows my father has any doubt about where my love of books and theology comes from! One of the advantages of living in Stoke-on-Trent is being in easy walking distance of my parents’ home. As I get most of my mail delivered there, I have regular cause to visit and to receive my father’s chiding for my failure to bring his beloved daughter-in-law with me. Wanting to spend time with us both together—or, rather, to get to spend more time with Susannah—and knowing our morning routine, on Wednesday he walked to Starbucks and intercepted us there.

One danger of a commitment to third spaces!

In our previous post, we mentioned that we were going to be joining some friends on a walk near Shrewsbury. The walk was last Saturday and the day could not have been more perfect. We hiked for about four hours on a route around the Long Mynd in the Shropshire hills.

Our walking party ended up in a pub for a well-earned meal, and we ended the day in Shrewsbury, which is a picturesque market town, with one of the more impressive train stations in our area.

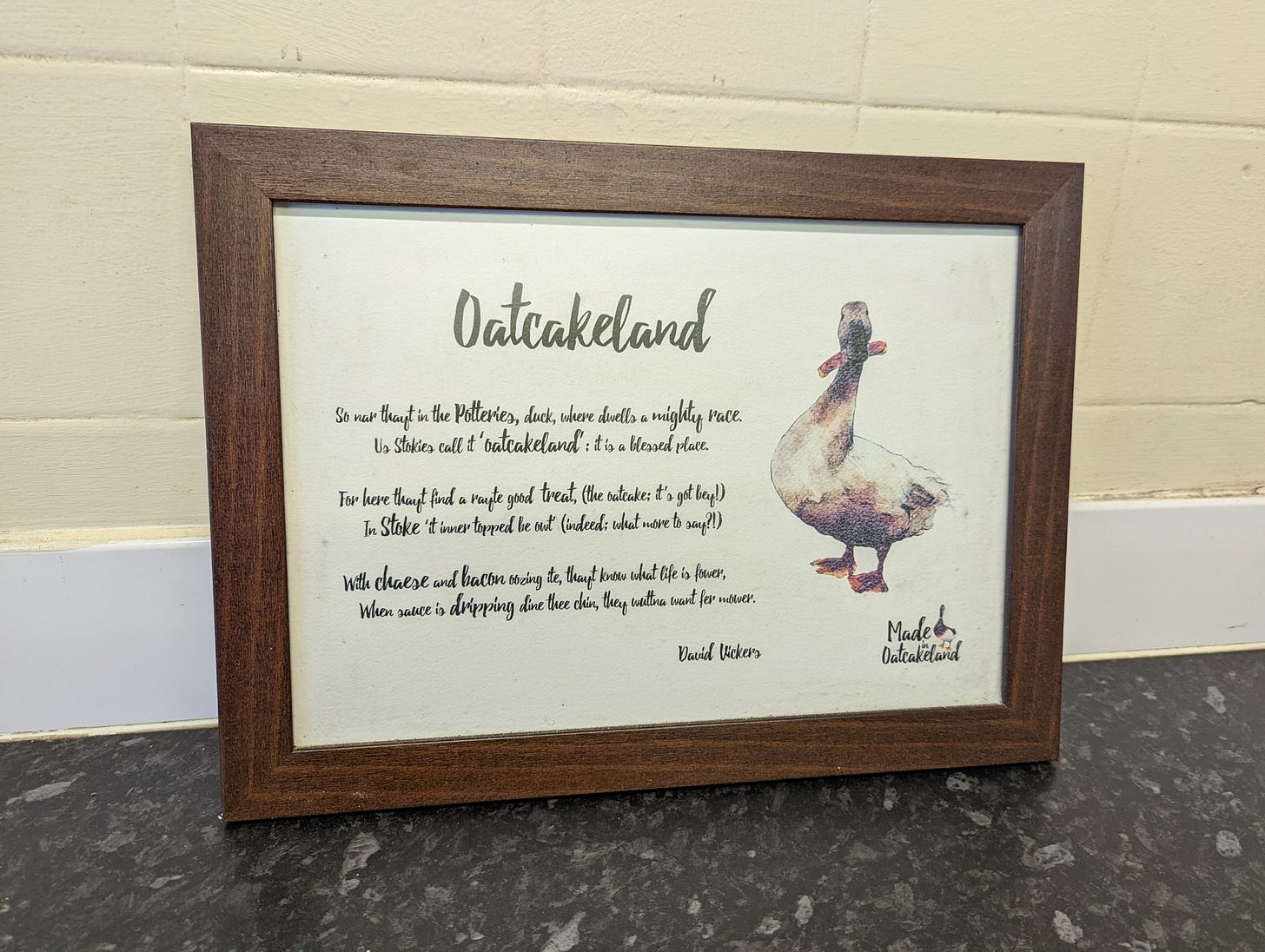

Our home city (one of them—the other of course is New York City) of Stoke-on-Trent is an amalgamation of six towns: Hanley, Fenton, Burslem, Longton, Stoke-upon-Trent, and Tunstall. Famous for its potteries—it is still widely called The Potteries—it used to be a heavy industrial city, with important coal-mining and steel works in the area. Almost all of the heavy industry has now closed down and the potteries employ only the smallest fraction of their former workforces. Nevertheless, it has its own quintessential culture, dialect, and way of life.

It is not difficult to find things to love about Stoke. It is enviably situated in the country. As Stoke is a key station on the West Coast Mainline, Manchester and Birmingham are both accessible in well under an hour and London in about an hour and a half. Some of the most spectacular countryside in England is also on our doorstep in the Peak District.

As a polycentric city, Stoke is perfect for pedestrians like us. We can walk to everything that we need in under fifteen minutes. Stoke-on-Trent City Council also just announced plans for a very light rail system throughout the city, which will make things even more convenient.

We walk a lot every day, especially at the moment, as the colours and the light of autumn is so arrestingly beautiful. As Susannah mentioned in our previous post, Trentham Gardens with its grounds that were designed by Capability Brown, is less than ten minutes away from us.

There are many other pleasant places nearer by, in easy walking distance.

Perhaps surprisingly, much of Stoke’s appeal comes from the way that it has repurposed and reclaimed the material legacy of its industrial past.

With its potteries, Stoke used to have such terrible air quality that one could not see from one side of the road to the other. James Greenwood described the experience of Longton’s air quality in 1875:

As I approached the place from Fenton, the choking smoke that blew from Longton in my direction forced me to cover mouth and nostrils with my pocket-handkerchief; but, advancing towards the main street, I discovered the utter futility of the precaution. It was as idle as shutting one’s mouth with the head held under water as a safeguard against getting drowned.

There was not the least use in sneezing and coughing; there was literally nothing for it but to breathe chimney smoke, or to turn and flee to purer air before it was too late…

I have not the faintest hope of doing justice, by any description of which I am capable, to the smoke of Longton... the moment it beset me I became a victim to its obfuscating influence, and, filled with smoke in every crevice and cavity, had for the time barely sense remaining to gasp and grope my way.

The nearest approach to it that I had ever previously experienced was a very foggy day in London. But London fog is a mild and pleasant mixture compared with the subtle concoction that comes pouring out of the pottery kilns.

The city used to have vast and unsightly slag heaps from its mining operations. As a formerly prominent site of heavy industry, the city also has lots of old railways in the area and the Caldon canal and the Trent and Mersey canal running through its heart.

Bottle kilns that once belched smoke are now attractive and distinctive landmarks of the Stoke-on-Trent urban environment. Slag heaps and other industrial wasteland have been reclaimed as parks, there are several vintage railways in the area, formerly polluted sites like Trentham Gardens have been restored, the grand architecture of our industrial past can be appreciated in ways that would have been impossible in the grime and soot of past centuries, and the canals now provide glorious calming paths through the city. We walked along the canal just down the road from our house a couple of days ago and took a few pictures.

Recent Work

Alastair: Over on the Theopolis podcast, having finished our recent series on the Epistle of James, we devoted two episodes to questions from our listeners. In the first of the two episodes, we discussed church office, the absent Ark of the Covenant in the second Temple, and Paul’s behaviour in Acts 23. In the second we discussed the difficult question of what to look for in a church when we are considering joining it and the question of how to regard the choice of church more broadly.

Within the podcast, one of my cohosts, Jeff Meyers, reminded us of a passage of C.S. Lewis’s book The Screwtape Letters. Framed as the correspondence between an older and younger demon, Screwtape and Wormwood, the book humorously explores various ways in which Satan and his minions seek to waylay the righteous by their cunning. In one of the letters, Screwtape rebukes Wormwood for his failure to address the commitment of his ‘patient’ to his local parish church:

May I ask what you are about? Why have I no report on the causes of his fidelity to the parish church? Do you realise that unless it is due to indifference it is a very bad thing? Surely you know that if a man can’t be cured of churchgoing, the next best thing is to send him all over the neighbourhood looking for the church that “suits” him until he becomes a taster or connoisseur of churches.

The reasons are obvious. In the first place the parochial organisation should always be attacked, because, being a unity of place and not of likings, it brings people of different classes and psychology together in the kind of unity the Enemy desires. The congregational principle, on the other hand, makes each church into a kind of club, and finally, if all goes well, into a coterie or faction. In the second place, the search for a “suitable” church makes the man a critic where the Enemy wants him to be a pupil… So pray bestir yourself and send this fool the round of the neighbouring churches as soon as possible.

Recently, I reflected a little upon the significance of evangelicalism’s widespread abandonment of parochial ecclesiastical order, perhaps most famously exemplified in John Wesley’s ‘The world is my parish’ statement. Lewis’s sense that rejection of—and, perhaps also by implication, absence of—parochial order risked elevating principles of affiliation that were considerably less catholic than locality seems to me to offer important insight into a characteristic weaknesses of evangelicalism as a movement.

In England, our fundamental reality of ‘place’ is something that has been powerfully formed by the Christian church. Throughout the country, church towers and steeples serve as landmarks. The graveyards surrounding many church buildings manifest the deep intergenerational rootedness of Christian communities in specific places. Minster communities served as model communities and seeds of wider habitations. Historic routes of pilgrimage are found in various parts of the land. The entirety of England is divided into bounded parishes and dioceses.

Unsurprisingly, the USA presented a very different situation due to various peculiarities of its history and geography: its vast extent, the unevenness and recency of its settlements, the greater mobility of its population, the moving frontier, and the organization of so many of its towns and cities around the automobile. A more footloose form of church order was always going to have advantages over a parochial system in many parts of such a country.

However, the sort of church order that typically develops in societies for which the automobile, mass media, democracy, and the free market are the more powerful socially organizing principles will be distinctive and susceptible to specific problems. As Lewis appreciated, without commitment to a robust parochial order, people are likely to affiliate on ideological, socioeconomic, temperamental, factional, generational, political, racial, or other grounds, in ways that are quite divisive of the Body of Christ. As such division resides in the very manner of the generation of such churches, it can continue to be operative even when people don’t leave or divide from the churches that they join.

In such an environment, the organic connection between a community firmly collectively grounded in a physical place and the church’s ordained ministries can easily become attenuated and the weight of the concept of ‘church’ can come to rest more heavily upon its ordained ministries, informal congregational life being limited in its scope. Rather than being a thick and concrete reality into which the ministries of the church operate, ‘community’ must increasingly be ‘astroturfed’, being an ersatz sociality generated by the church to attract potential congregants. That such a form of church order would be more susceptible to personality cults developing around leaders should also not surprise us.

Churches and their attendees can come to relate as if they were businesses and consumers. Rather than pastors speaking to their locality in its breadth, they can focus on appealing to critical segments of a vaguer religious marketplace with other local congregations as competitors. Christians can start to think of their churches as if they existed to serve their consumer preferences. Such churches will also have very different sorts of relationships to their neighbourhoods, something that will often be manifest even in the functionality, anonymity, and insularity of their buildings. Because locality is considerably less of a principle of their existence, there may be rather less of a natural pressure upon them to be good neighbours and servants at the heart of a community over several generations. With a weaker rootedness in locality, I suspect evangelicalism has also been more prone to being overwhelmed by its own form of consumer culture, with media, celebrities, large events, and the like filling the absences of thicker community and local culture. It has also made it less apt to bear the tradition of the church in its catholicity, as that catholicity constrains its ability to target itself to specific groups.

I have long been fascinated by the ways that material reality in its various forms—technology, geography, economic reality, etc.—drives many things that we regard in narrowly ideological terms. Ecclesiology is an exemplary case here: whatever people’s doctrines of the church and whether we welcome them or not, I suspect that by far the greatest factors shaping the form of church order we work within are material ones. It would be welcome to see more conversations about our doctrine of the Church and reflection and deliberation concerning its practices registering this.

Now, of course, things are seldom so straightforward on the ground. People can be trapped in parishes filled with nominal Christians and it might be prudent from them to travel to worship elsewhere. In many other contexts, people have put down deep roots in a locality quite apart from any parish system. And few evangelicals are not seeking to counteract any of the characteristic weaknesses that I mention.

❧ I am one of the writers published in the Davenant Institute’s recent volume, Protestant Social Teaching: An Introduction. I joined my friends on the Ad Fontes podcast to discuss my chapter. We got into all sorts of questions, including the way that the rite of circumcision relates to the Apostle Paul’s—and St Augustine’s—teaching about ‘the flesh’. I’ve also written on my understanding of the Abrahamic sign of circumcision here. I further discuss the significance of the circumcision of Christ in the gospel of Luke in this video.

❧ Things have been relatively quiet on the Mere Fidelity front recently, especially as Derek has been on paternity leave. We had a long Q&A session (exclusive for our Patreon supporters) and our latest episode was an interview with Dr Todd Hains, discussing his new book, Martin Luther and the Rule of Faith: Reading God's Word for God's People. Peter Leithart joined us for this week’s episode to discuss his new book, On Earth as in Heaven: Theopolis Fundamentals.

❧ Over the last few weeks I’ve taken up a large new knitting project, my first in several months.

Upcoming Events:

Today we start the latest session of the Civitas group. Run by the Theopolis Institute, Civitas is a series of extensive discussions of political theology that has been ongoing for a few years now, with a group of select group of participants from different viewpoints, working to develop a common vision.

We will be up in Durham (not North Carolina!) to visit our godson from the 2nd to the morning of the 8th November. After that we will be down in London again. If you are in either of those areas and would like to meet up, get in touch with us!

Until next time,

Alastair and Susannah

Thank you for sharing your love for your people and your place.

I also appreciated this section of your newsletter -- I have long been fascinated by the ways that material reality in its various forms—technology, geography, economic reality, etc.—drives many things that we regard in narrowly ideological terms. Ecclesiology is an exemplary case here: whatever people’s doctrines of the church and whether we welcome them or not, I suspect that by far the greatest factors shaping the form of church order we work within are material ones. It would be welcome to see more conversations about our doctrine of the Church and reflection and deliberation concerning its practices registering this.

It would be interesting to hear voices from South Asia, Southeast Asia, and other areas speak to this issue.

There is a certain logic here about how churches should work in a parish model and entertain a centered geographical presence in a neighborhood. Alastair and Susannah present a pretty common argument about how unintentional many evangelical or other churches are about "neighborhood". What you say perhaps rings true in a most basic sense. Churches should be a part of their community. But, in America and elsewhere we live in very different times and places than the ideal Stoke-on-Trent life put forward here. The interesting thing for myself is that western rural Pennsylvania looks much like central England.

However, England's countryside looks the way it does for a lot of reasons that depend on a global imperial footprint over the last several hundred years and the rise of global capitalism more recently. We should also probably remember that England is part of a restored nation and continent whose beauty looks the way it does because of post-World War II modernization and development, literally billions of mid-twentieth century American dollars borrowed by the UK for that very purpose. You knock the gentrification and colonizing ways of American evangelical churches from the very perch your own country and churches established with us and tried to perfect all across the world.

The church of Christ can certainly work within a parish-based system but not every locale renders such a model sufficient for kingdom work or remains all that helpful. What would parish life look like in Hong Kong or Mexico City? Or, how about Dallas, Texas or New York City? There is certainly something to be said for purposeful living in a particular community and intentionally serving a particular neighborhood, but what really is a neighborhood in today's society?

I ask the age-old question about who is our neighbor and what is a neighborhood because it's still very relevant to the purpose and life of the church. Times and places change, so how does the church effectively serve its sphere of influence in a world where borders, locale, and even the notion of face-to-face proximity are often disappearing into thin air. Living as a community is certainly important but what does that look like in the vast open spaces of rural America compared to the isolated garden life of central England? And, what of America's swelling metroplexes and the myriad number of smaller cities and towns that dot a landscape forty times the size of England alone?

Further, what of hangouts on Discord or the massive communities of video game enthusiasts that themselves are the size of the very cities and towns in question or even larger? How about the Facebook groups and constant communication and presence we enjoy from others online? The public square has moved from the town square and seats of castle-inspired power to Twitter, Facebook, and many other "places" that exist on massive server farms quite apart from the physical location of the community's existence.

So, in one sense I'd very much like to agree with you here but given the state of our technological society and its continued sociotechnological innovation I don't see how the parish system as framed is going to work in any way similar to how it has in the past. We might also consider that the parish system developed in what we call Europe today more broadly not because it was biblical necessarily but because relevant social institutions decentralized as the Roman Empire fell to pieces. Something had to take Rome's place and the parish system gradually developed as a result along with monasteries and feudal societies. The other historical question we might ask is whether the parish system has really worked in England at all since only about 2-3% of the people even go regularly to a parish church in a country that was once thoroughly Christian. Are we really to believe that the very system of ecclesial life in question had nothing to do with the vast unfaithfulness that exists in what was once the very model of Christendom?

Such a contention seems sociologically problematic and so there is more here to discuss. Britain is what she is today precisely because of her work in the rest of the world, a social and political superstructure she was very instrumental putting in place. The church has an obligation as a matter of mission to the whole world and especially to the world that English Protestantism as a matter of empire and economic endeavors made possible. The genteel life of Stoke-on-Trent exists because all the industrial manufacturing that once clouded its skies now takes place in places like Malaysia, Vietnam, China, and Mexico. Those communities face all the challenges of a booming industrialization while English clerics might rejoice in what a beautiful green place Shakespeare's home now is. But, the truth is that the neighborhoods of Shanghai and Guadalajara are filled with people that don't know Christ and aren't the product of a near two thousand year presence of Christianity in their neighborhoods.

So, I get it. We need to be intentional in our communities but we can't treat this topic with the sort of green-treed picture heavy romanticized appraisal of neighborhood that makes us think we all should live in a Shire like nice little hobbits with that occasional episcopal visit by Gandalf, dragon fireworks and all. We do ourselves and the church no favor by pretending life is something other than what it is now or that we ought to concentrate in the main on those physically closest to us. Our mission is the Great Commission and not setting up and maintaining a great neighborhood or town. And, look, I live in a post-industrial town in western Pennsylvania that could double for whatever you find in the English countryside minus what has been there over a thousand years. But, our focus can't merely be where we live because the gospel in the main has never been just about that reality. The gospel does transform neighborhoods and cities but we don't do that without keeping our focus on the continued proclamation of God's word to the whole world.