№ 22: Niece-Maxxing

In which Susannah mostly sort of ignores geopolitics and Alastair has thoughts on victimhood and agency. Also, Jeroboam.

Dear Friends,

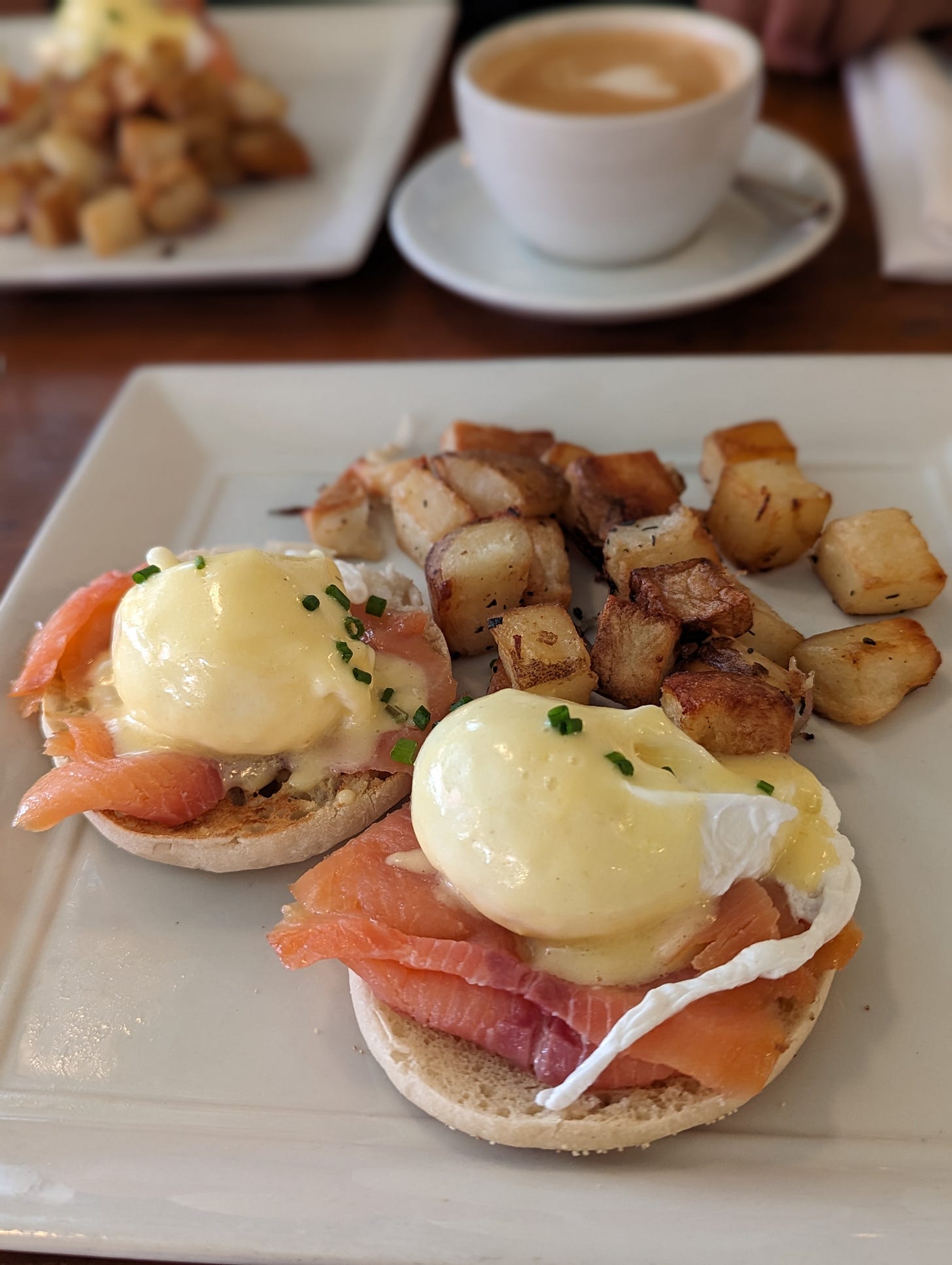

I’m writing you from yet another airport departure lounge. The thing is, Alastair has this strong belief that these substacks should encompass seasons of our lives, which means that a neat bow at the end of a couple of weeks is the end of a phase, marked by (usually) one of us following the other of us to wherever the other of us is. In this case, that’s Susannah (me) following Alastair across the Atlantic to England, after an extra three weeks in the US in which I basically stalked our eight-month-old niece. (Went to LA to visit for four days, then when she and her parents [yes, I love them very much too, but she’s cuter] came East, followed them up to our dad & stepmother’s place in Upstate New York, and then hung out with them MORE in NYC.)

I miss Alastair very much but again… the baby is an EXTREMELY good baby. And I probably won’t see her for another four months, at which point she’ll … I don’t know, be in high school, or be the Speaker of the House.

I said no geopolitics and that’s mostly true but the thing is, starting about a month before the war, I had begun getting… curious, I guess, about my own Jewishness; about what it means to be Christian and Jewish at the same time (if that’s a thing). Just in time for that question to get … a lot weirder. I’m thinking and reading. And the question of Zionism seems somewhat separate, although a lot more pressing now than it was a month ago.

Among the things I have read in the last three weeks:

Jonathan Sacks, A Letter in the Scroll (well, half)

Rich Cohen, Israel is Real

George Eliot, Daniel Deronda (again, half: no spoilers. This one is because Mom is currently reading it and as soon as I started getting embroiled in “I’m an Anglican! But also, I am a Jew!” interior drama she prescribed it to me.

Bits of:

Jon D. Levenson, The Love of God: Divine Gift, Human Gratitude, and Mutual Faithfulness in Judaism

Daniel Gordis, God Was Not in the Fire: The Search for a Spiritual Judaism

…and a whole bunch of other miscellaneous things.

Anyway, that’s my current status. I would be very grateful for any book recommendations, advice, thoughts, and so on.

Last night, coming home for my final night at the apartment until we return in late February, it became clear as I approached the street that something was UP. What was up was two blocks worth of absolutely crazy Halloweening: I’d say thirty brownstones decorated into trick or treating palaces, everyone out on stoops giving out candy. I took a shift in front of our building, talking to neighbors and learning about this new and terrifyingly energetic block association that has taken off since the pandemic. Alastair and I are going to join. I’ll let you all know if, as seems not impossible, it turns out to be some sort of real estate based cult.

In half an hour of candy distribution we probably had at least fifty kids come by—and it was mostly young kids with parents, plus older kids without and the occasional teen.

This is localism on steroids. I don’t even know what this is. I’ve never seen the Upper West Side be quite this ferocious about Halloween—gotta say I’m in favor.

That we won’t be here for Christmas is painful—but it will be so good to spend Christmas with Alastair’s family back in England.

Alastair: We really have been neglectful of this Substack of late; it has been over a month since we last posted here. Susannah and I have been on different sides of the Atlantic for much of the time. I arrived back in the UK on the 10th, while Susannah doesn’t return for a couple of days yet.

The last week or so before I left New York was an enjoyable one. As we knew that we wouldn’t be back together in New York until spring of 2024, we filled the evenings and weekends remaining to us with lots of activities and time with friends and family.

On September 28th, we attended the launch of The Liberating Arts: Why We Need Liberal Arts Education, a new book from Plough. Roosevelt Montas, Jessica Hooten Wilson, Zena Hitz, and Jonathan Tran all gave thought-provoking talks, which were followed by a stimulating panel discussion and question and answer session.

I found myself thinking about some of the issues raised in the evening over the days that followed. In particular, I was led to reflect upon an issue that almost all the speakers circled, without ever addressing it head on. The speakers emphasized the ideas, values, visions, and sensibilities that are conducive to the study of the liberal arts. However, the importance of formative communities and their constitutive practices seemed to me to be a matter worthy of greater exploration. For instance, in something like the practice of Sabbath or Sunday both Christians and Jews are formed into ideals of democratized ‘leisure’ (in the thicker sense of that term) and communal contemplation. Sabbath frees us all from the tyranny of the quotidian, hallowing a time for collective meditation upon that which transcends the immediate. Churches and certain other religious communities can also foster a sense of humanity, present an extensive and aspirational social horizon, and afford hospitable contexts for formation in the liberal arts that would be lacking without them. While not everyone within them will devote themselves to rigorous study of the liberal arts, it is in such contexts that they will most flourish and in which their true ends will be most apparent.

On the Saturday my latest Davenant Hall class, on John and Revelation began—we are now four weeks into it. It has been delightful to look at the book of John in depth again; it is an incredibly rich text and, every time that I revisit it, I am struck by some new facet to it that I had missed before.

On Sunday morning, before the main service, I taught the second of my three-part series on reading the Bible, exploring the subject of symbolism in Scripture. In the afternoon, I met up with a friend for a meal. Due to my teaching commitments, I hadn’t been able to join Susannah on her brief trip upstate. Unfortunately, she didn’t have her key with her, so I had to head back home to let her in!

We joined several other friends for a birthday party in the city that evening.

The rest of our final week together in New York was a busy one, but we were able to meet up with some friends who moved into our area for evening prayer on the Thursday. On the Friday evening, we had some friends over for a video evening, watching The Lady Eve. As I have never watched any screwball comedies and have seen very few musicals, Susannah has been concerned to address these gaps in my education. Over the week, we also finally finished watching through Jeeves and Wooster

I had decided to delay my return to the UK until after the wedding of some friends of ours—and one of Susannah’s closest friends. The wedding was a remarkably joyful one; the groom even composed a piece of music especially for the occasion. We had arrived at the wedding in a downpour, but the weather had cleared up by the time we left the reception and we passed a pleasant few hours in the city, walking around and browsing in the Strand for a while.

Sunday was my last full day in the city before I flew out. I delivered my final study on reading the Bible, discussing typology and theology. It was a blessing to have such a thoughtful and engaged group and I hope that I will have similar opportunities again in the future.

In the afternoon, some good friends of us came over and cooked a meal for us and we played Black Orchestra together, in which we succeeded in defeated Hitler. Getting into playing board games again has been delightful.

Before I left on Monday, we had a long walk in Central Park. The flight and train ride back went smoothly, although I was wiped out on my return, having not slept at all.

The weeks since returning to the UK have been relatively quiet. I have been settling into a routine again: lots of reading, writing, and recording. I have also appreciated the opportunity to see family again.

My friend Dave visited on the 15th and I enjoyed a meal with him and his family in the evening. Dave and I have known each other for the best part of twenty-five years now. We set up a Bible study group shortly after we first got to know each other, which was extremely formative for both of us. It is always a blessing to see him again.

Stoke is an extremely deprived city, but it has its attractive aspects. There also seems to have been some money invested in our area over the past months, and several of the stores that have not closed are undergoing renovations, which is an encouraging sign for an area that is generally rather lacking in them.

Since my return, it has been wonderful to spend more time with my parents. My dad’s health continues to deteriorate markedly and he often falls and struggles to do many basic tasks. However, being able to see a lot of him and my mother during these days is a blessing for which we all feel particularly grateful. On Wednesday the 18th, we had afternoon tea together with my sister-in-law Fernanda, who was helping my mother with some work in the house.

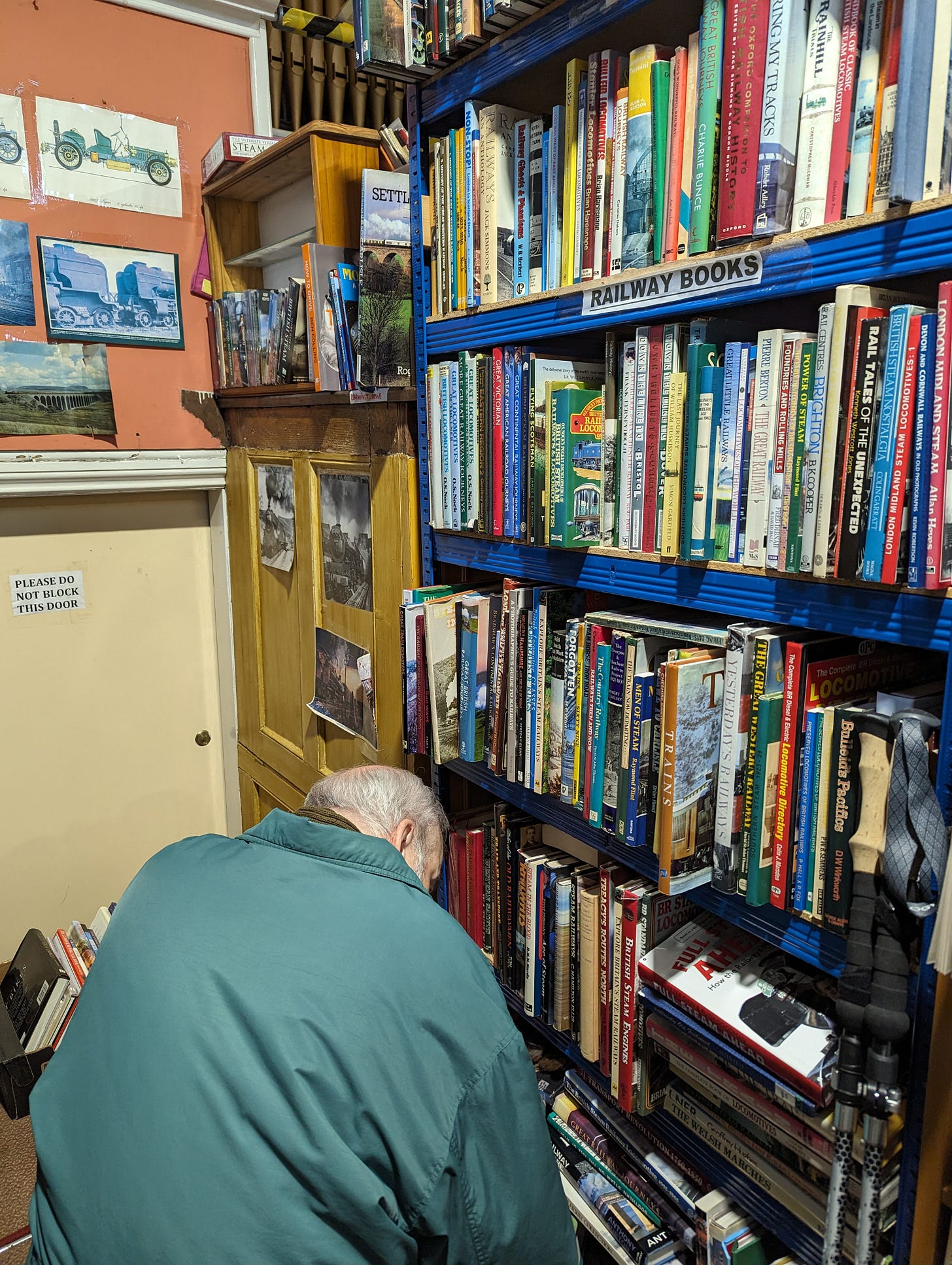

This last Friday, we went to the Alsager Book Emporium together to donate some of the remaining books from my father’s library. We have spent countless hours over the years browsing their shelves together, and this time I was able to pick up several great volumes for an astonishingly low price.

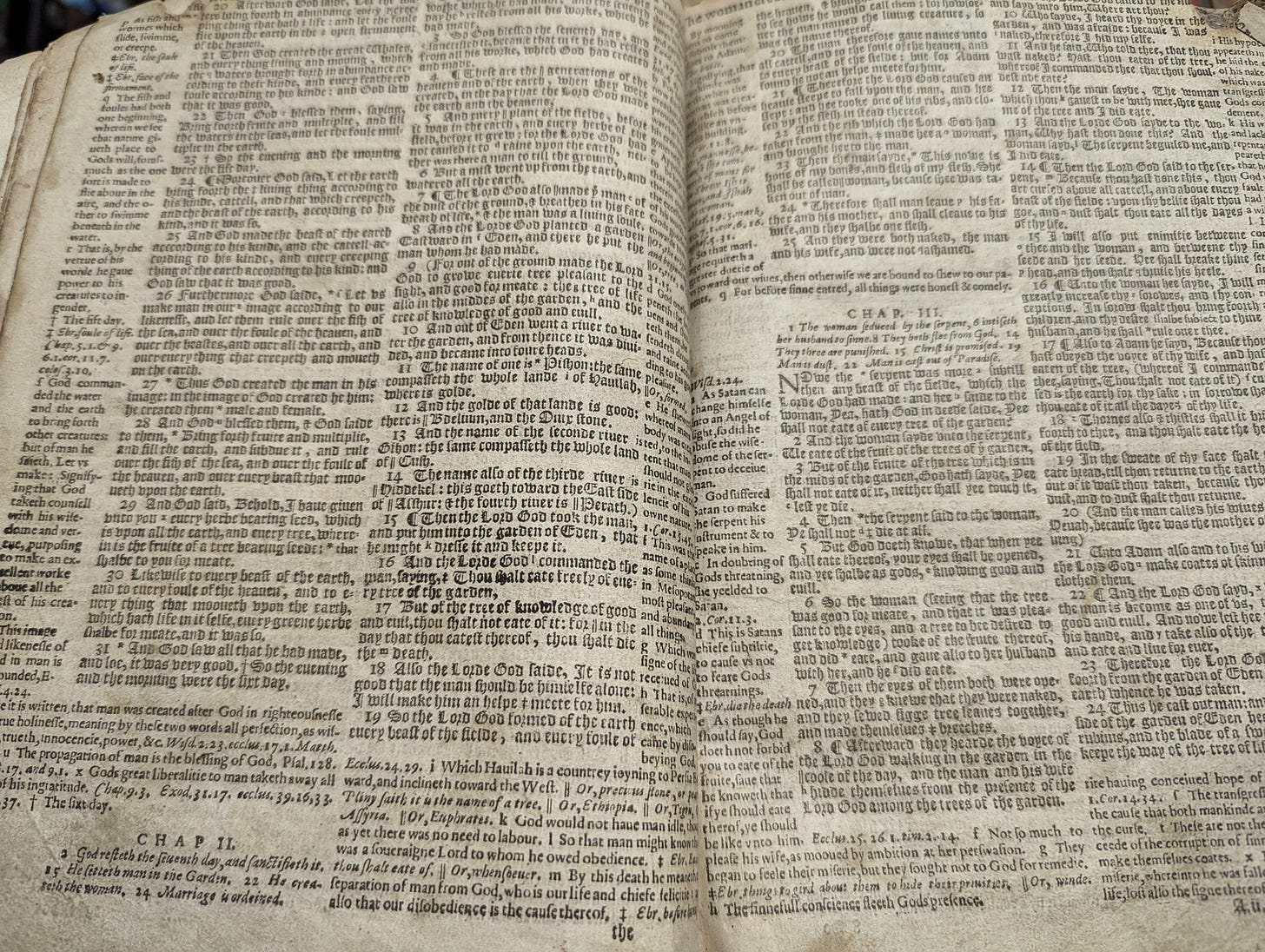

They also had a copy of a Geneva or ‘Breeches’ Bible from the end of the sixteenth century, through which, as someone who has long been enthusiastic about old Bibles, I greatly enjoyed looking.

I preached on Sunday, on the animating reasons for Christian living, from 1 Peter, after which I had a meal with my parents. The last few days I’ve been trying to get as much on top of my backlog of work as possible, in preparation for Susannah returning tomorrow.

Restoring Responsible Action

The horrific atrocities committed by Hamas on October 7th, the immense loss of life in the conflict that has followed, especially in the Israeli bombing of Gaza, and the various reactions to the situation in the US and the UK have been greatly occupying our thoughts and provoking our prayers over the past weeks. It has been both dismaying and revealing to observe not only the extreme polarizing effect the news has had in the US and UK, but the fierce and vocal antisemitism that has surfaced in its wake.

Even within the years since 2010, several bloody wars have occurred in the Middle East. Over half a million people have died in the Syrian Civil War, over 350,000 in the Yemeni Civil War, and over 150,000 in Iraq. While these conflicts have received a lot of attention in Western media, their impact upon the Western consciousness has been arguably relatively minor by comparison with that of the current conflict between Israel and Hamas.

The state of Israel, the Jewish people more generally, and the plight of the Palestinians are realities. But they are also media events that have served as powerful props in domestic and international political and ideological psychodramas. They have come to stand as concrete symbols of and lightning rods for broader commitments and tensions. This, of course, takes many different forms. For some Christians, most notably dispensationalists, the Jewish people and the state of Israel are the often-effaced objects of benign projections on account of the expected role that they will play in an envisaged eschatology or through a sort of religious orientalism. Israel is seen as the ‘Holy Land’, within which many of the most sacred sites of Christianity and Islam are found. Many other forms of Christianity over the centuries, on account of Christianity’s historical origins in conflict with other Jewish sects and their doctrines, and its subsequent development into a Gentile-dominated movement, have treated the Jews as the archetypal foils and antagonists for true Christian religion.

Within Western antisemitisms Jews have long variously served as contradictory symbols of capital, culturally destructive intellectualism and ideology, atheism, archetypally false religion, malign and self-serving elite powers, and unassimilated particularism or globalizing cosmopolitanism. After the Holocaust, Jews have borne great symbolic freight as the foremost historic victims of extreme European nationalism and xenophobia, especially in their fascist forms—‘Never Again’.

The exceptional status that the Jews occupy in the Western imagination cannot be dismissed as nothing more than a projection. As a people, the Jews are and have been genuinely exceptional in many respects: they have been an immense influence in the development of Western society and thought, and they stand in a unique relationship to Western society and to Christian and Islamic religion.

For many on the left, the state of Israel has become the great symbol of ‘settler-colonialism’, the power of Western imperialism, nationalism, whiteness, fascism, apartheid, and genocide. The Palestinians are an archetypal oppressed party and, in the agglomerative coalitions of contemporary progressivism, symbolically function as the vanguard of the great struggle against Oppression and Oppressors in all their guises. Struggles related to race, gender and sexual identity, socioeconomics, religion, colonialism, and nationhood can all be projected onto their plight, often in ways that might leave spectators scratching their heads.

As Palestine becomes the screen onto which a vast array of forms of oppression are projected—each having an existential urgency for those who feel themselves to be suffering from them—Palestinian liberation will come to represent a matter of absolute justice, beyond debate, negotiation, complexity, or compromise. As the obstacle to this for many, the very existence of the state of Israel—and even of Jews—can come to be felt as something akin to a moral offence.

In light of this, any consideration of the Israel and Palestine situation requires of us a difficult exploration of deep and dark recesses of the Western imagination (this is not the place and I am not the one to discuss the complex role the situation evidently plays in the Islamic imagination). As a concrete focus and object of deep impulses of Western imaginations, much is revealed about our societies and ways of perceiving and inhabiting the world by our various responses to the situation in Israel and Palestine.

There are few things more effective in forging and galvanizing identities than wars. Such conflicts can come to define us and can also exert a powerful pull upon our judgments, drawing them into the orbit of our party’s interests. It has been illuminating and troubling to see over the past weeks how concern for or recognition of justice in one side’s cause in a conflict can lead many to regard the mere registering of evils or injustices committed against and/or suffered by those of another side to be threatening. In other quarters, a desire to avoid necessary yet complex judgments has led people to deplore such things as abstract ‘cycles of violence’ and try to apportion blame as evenly as possible, not reckoning with the very different relations in which parties stand to the situation. It is possible—and indeed essential—to avoid flattening out issues morally with evasive rhetoric or false equivalences, while keeping a firm grip on our sense of and concern for the humanity of those on the ‘other side’, whichever side we consider that to be. This is necessary not least when discussing matters such as a ceasefire, enabling us to see the scale of suffering on different sides, while also being clear about the shape of conflict.

So many of the questions surrounding Israel and Palestine are immensely thorny. The just interests and rights of two parties seem to have been placed in intractable conflict and great evils, atrocities, and injustices have been suffered (and sometimes committed) by people on both sides. There are incredibly difficult issues here, which those of us who are viewing from a distance and with limited understanding of the background are not equipped to litigate, even were it our place to do so. I will, however, bear testimony to the importance of long interactions and conversations with dear friends of ours with commitments and interests on differing sides of this present conflict. These have been morally clarifying.

While many of the issues in the broader conflict are fraught and difficult to judge well, this doesn’t mean that every moral question related to these conflicts is a difficult one. And, while those of us in the West should be very wary of casting definitive judgments about the Israel/Palestine situation more generally, it is important that we get certain key judgments right, especially as they have come to impinge upon our own politics, institutions, and ethnic relations. Whatever real background gives context to Hamas’s actions on October 7th, the actions themselves were deplorably wicked, Hamas is unequivocally culpable for them, and little possibility for peace seems to exist while they continue to function as the representatives of the Palestinian cause and interests.

It is important to cross-examine and understand the impulses of our thinking at such times. For instance, one thing that has become more evident is the power of fundamental conceptual frameworks, into which disparate realities will get forced and by which they will be assessed. In particular, the past month has exposed ways that agency gets distorted in certain frameworks.

The oppressor/oppressed binary tends to deny true agency on both sides. On the one hand, the agency of oppressors, as it is premised upon and perpetuates injustice, is fundamentally illegitimate, so cannot truly be moral or responsible, only variously blameworthy. When power gets pathologized, powerful people—or people who are rhetorically or politically placed into the “powerful” group—can increasingly become preoccupied with managing their own complexes of guilt and pursuing atonement, rather than with confidently, prudently, and responsibly exercising good power and authority that serves the common good. The oppressed, on the other hand, get presented as victims determined by the perverse agency of their oppressors, free of blame because lacking in self-determined agency, yet consequently lacking in true moral agency or responsibility.

In such a framework, morality can be sought in radical internalization of guilt and blameworthiness, abnegation of legitimate agency and selfhood, and/or hyper-deferential treatment of perceived oppressed persons on the oppressor side. On the side of the oppressed, it can come from leaning into one’s own victimhood and commitment to accusation of oppressors. Responsible and good moral agency is barely a possibility in such a system (of course, such systems can be applied in inconsistent, non-totalizing, and arbitrary ways). Even when those who identify with victims gain real power, they can disavow or displace it in various ways.

People who are granted to wield real power or authority, yet cannot fully be held responsible or accountable for it, also enjoying some immunity to challenge on account of their identification with or even as victims, are incredibly dangerous. Great power without a corresponding great responsibility is a huge liability.

Such perverse visions have very much been in evidence in debates about Israel and Hamas/Palestine. When armed men of an ‘oppressed’ class burn defenceless infants of an ‘oppressor’ class alive, it reveals aporiae in many approaches to intersectionality. Likewise, when people in the West identifying with the ‘oppressed’ class in the Middle East are increasingly intimidating a smaller minority in their own societies they regard as identified with a middle eastern ‘oppressor’ class. The questionable character of the categories becomes more evident in such circumstances.

The last month has exposed some of the moral bankruptcy of certain of the critical theories that are dominant in many quarters of the academy and society. As victims, Hamas cannot truly be blamed and, as they are deemed fundamentally illegitimate, Israel cannot exercise agency in response. When an official spokesman for Hamas recently declared that, as Hamas are victims, everything they do is justified, he was expressing a perverse logic that is, in related forms, deeply embedded in many quarters of our own societies. Sadly, where Palestinian authorities hold such an attitude to their agency, it is not at all clear to me how any ‘peace’ can be had, or even if there can currently be any live case for a Palestinian state (despite the Palestinians’ legitimate moral claims to one more generally).

The dynamics of such situations can also bear similarities to situations of abuse. Vicious and abusive parties can easily lay responsibility for their violence and abuse at the feet of people who ‘provoked’ them. Such a dynamic has been evident in the way that belligerent supporters of Palestine have been appeased by British authorities in certain contexts. Recognizing the capacity and willingness of such groups to engage in violence and other disruptions of the police, such authorities have sought to remove anything that might excite their anger, such as posters of hostages. In such a situation, it will be those challenging the abuser who will be held responsible for the breach of the ‘peace’ that occurs when the abuser is provoked and explodes. The abuser will not be held responsible, because everyone is too afraid of and/or powerless against them.

If, operating within the framework I’ve described, Israel were to assume a posture of victimhood, it could also shrug off the moral responsibility that should characterize the actions of those with power, laying all responsibility at the feet of Hamas, who first acted against them. All responsibility for lives lost in collateral damage supposedly belongs to Hamas and if, by comparison with Hamas, Israel is less indiscriminate and brutal in its methods, they must be the good guys. In such situations, it is very easy to grade ourselves on a curve: provided that we think ourselves less vicious than our adversaries, we must be the good guys and our actions must be just.

While the purposeful intention of the deaths and suffering of innocents, as on October 7th, is very different from actions of war aimed at combatants and military targets—loosely observant of principles of discrimination and proportionality—in which civilians are killed, in such situations subtle casuistry can easily dull consciences to the moral gravity of such shedding of blood. While some such actions of war may be ‘justified’ in some sense, we should not allow ourselves to be hardened to the reality that they nonetheless represent grave ‘evils’ (in a slightly broader sense of the term) and must never be regarded permissively. Those who engage in such actions must register their weight, mourning them, recognizing the immense accountability of all who shed blood, and soberly seeking God’s mercy. It is also important that an intoxicating sense of the justice of one’s cause does not lead to blindness or indifference to prudential consideration of the real-world consequences of one’s actions. Somehow war must aim at a realistic and workable peace.

And, of course, though some actions in war that lead to shedding of blood are justified—not all are. Jus in bello is most important when it is most difficult to carry out. That’s when the rubber meets the road. Even in terms of international laws of warfare, which are less demanding than Christian and Jewish principles of just war, there must be a contrast between civilians and combatants. Military actions must be proportionate to the military advantage they seek. Military action must be deemed necessary to the end of defeating the enemy. That Hamas did not even make an attempt at the just prosecution of war, that their espoused principles are to violate the distinction between civilian and combatant, and to make war in the most brutal way possible against innocent targets, makes it all the more urgent that Israel refuse these tactics entirely.

It is imperative we recognize the perverse character of the way that the oppressed/oppressor framework tends to operate and adopt a very different approach, one which allows us to identify the agency and responsibility proper to various parties and to hold all to a proper degree of moral accountable. Beyond this, we need to encourage and equip people to move towards higher forms of agency: elevating moral capacity, self-control, ownership of action, etc. This encouragement must not be chiefly accusatory but liberative, idealizing growth of the capacity to act well (here one might question whether Israel’s policies have sometimes involved a deliberate encouragement of the perversion of Palestinian agency, to legitimate denying them any).

The perverse and dangerously simplistic moral framework I am describing, though currently very evident in discourse surrounding Israel, Palestine, and Hamas, has considerably broader effect and numerous iterations.

We need something better.

Jeroboam’s Inverted Exodus

The story of Jeroboam is the story of an exodus gone wrong. In him we see aspects of the characters of Joseph, Moses, and Aaron.

Jeroboam is a gifted young man of the tribes of Joseph. He is raised to prominence—over the forced labour of the house of Joseph—by an increasingly Pharaonic King Solomon (1 Kings 11:28).

Encountered on a journey in the open country by the prophet Ahijah, a garment is torn and Jeroboam is given a vision of future power over his brothers (1 Kings 11:29-39), much as in the story of Joseph in Genesis 37.

As the Judahite Solomon seeks to kill Jeroboam, he flees to Egypt (1 Kings 11:40).

Like Moses, hearing of the death of the man who sought to kill him, Jeroboam returned to the land and delivered a message to the king, calling for him to loosen their burdens—‘let my people go!’ (1 Kings 12:2-5). The king’s heart, however, was hardened by the Lord and he increased the burdens.

After the split of the kingdom, Jeroboam played the part of Aaron. He established two golden calves: ‘behold your gods, O Israel, who brought you up out of the land of Egypt’ (1 Kings 12:28-30; cf. Exodus 32). He instituted a false feast and excluded the Levites from the idolatrous service.

The man of God out of Judah is like a new Moses. He spoke of the breaking of the altar. It will be reduced to dust and its ashes poured out, like the tablets of stone were broken and the dust of the destroyed calf poured on the waters in Exodus 32, after the people’s sin with the golden calf.

The Lord declared that he would ‘burn up the house of Jeroboam’ in 1 Kings 14:10. Jeroboam’s son Abijah died and then his son Nadab was cut off after two years, with all of the rest of Jeroboam’s house. Nadab and Abijah should remind us of Aaron's burnt sons, Nadab and Abihu, who were burned up by the Lord in Leviticus 10.

Recent Work

Alastair

❧ For the fiftieth anniversary of J.I. Packer’s classic Knowing God, we had Dr Fred Sanders on the Mere Fidelity podcast to discuss evangelical spirituality. Kevin Vallier, author of All the Kingdoms of the World: On Radical Religious Alternatives to Liberalism and leading critic of integralism’s philosophy of church and state relations, joined us for a discussion of it. We recently devoted an episode to Andrew’s scintillating new book, Remaking the World, and now it is Matt’s turn with his Called Into Questions: Cultivating the Love of Learning Within the Life of Faith, an updated version of an older book. We were joined by special guest Brad East for the discussion.

The Theopolis Podcast’s series on Deuteronomy continues with episodes on Deuteronomy 18: Priests and Levites, Deuteronomy 18: Abominable Practices, and Deuteronomy 19: Cities of Refuge.

❧ My series on the book of Revelation with the God’s Story Podcast continues with episodes on the vision of the Woman and the Dragon in chapter 12 and the sea and land beasts in chapter 13.

❧ I wrote a blurb for Samuel Bray and Drew Keane’s How to Use the Book of Common Prayer: A Guide to the Anglican Liturgy:

This is a wonderfully clear and accessible guide, ably communicating the purpose of Christian liturgy, the rationale of the prayer book, and how it can be used most fruitfully. For any who are new to the Book of Common Prayer, this volume will serve to open a treasure to them; for those already familiar with it, it will deepen their understanding and appreciation.

I have written several blurbs for books over the last year, and probably should include them here in the future.

❧ The last video in my three-part series on the Exodus was posted by Theopolis.

❧ If you want a taste of the recent Exodus course that I taught for Theopolis, you can get it here: The Exodus Pattern in Scripture.

❧ My talk from the recent Protestant Theology of the Body conference is now available, along with the other talks from the conference, on the Greystone website.

❧ My article ‘Decoding the Bible’s Begats’, previously published in Plough, is in the November/December issue of The Catholic Response.

❧ In a summer with five weddings and two engagement parties, marital themes in Scripture have been very much on my mind! As I’ve been teaching on the books of John and Revelation, they’ve also been prominent in my mind in considering those books. I produced a short video for Theopolis discussing them.

❧ A couple of years ago, I was interviewed by Christian Heritage London and they published it a few weeks ago. You can listen to it here and watch a brief clip of it here.

❧ Digital Liturgies: Rediscovering Christian Wisdom in an Online Age is a superb new book by Samuel James. Within it he explores some of the ways that the Internet, especially social media, is shaping us and what we might do about this. It is very readable and accessible and will be valuable for a wide audience. He joined me to discuss it.

❧ My friend Jack Franicevich, a deacon and curate at Cornerstone Valparaiso and adjunct professor of writing at Valparaiso University, joined me to discuss his new book, Sunday: Keeping Christian Time. We talked about the scriptural teaching concerning the Sabbath, and how it relates to and can inform Christian understandings of Sunday, and of time more generally. Listen to the episode here.

❧ Neil Shenvi and Pat Sawyer joined me for a discussion of their new book, Critical Dilemma, and of their concerns about rising ideological movements in churches and other Christian contexts.

Upcoming Events

❧ Alastair will be speaking at the International Presbyterian Church presbytery meeting in York on the 25th November.

❧ The third UK Davenant Convivium will be on the 24th January, with Oliver O’Donovan as the keynote speaker.

❧ My Hilary Term Davenant Hall course, starting in early January, will be on ‘The Bible and Politics’:

The words and teachings of the Bible are frequently deployed and appealed to in our political discourses. Yet such engagement with the Bible is typically superficial and merely rhetorical; while the Bible affords shallow prooftexts and resonant turns of phrase, it is seldom serving as a deep and guiding source of wisdom in our political thinking. In recent decades, after a long period of neglect, the importance of the Bible’s influence in historic political reflection has received growing attention. In addition to considering such retrievals of the Bible’s significance as a political text for historic thinkers, this course will seek to discover more of the Bible’s enduring insight and generative potential for political reflection. We will investigate some of the variegated ways that the Bible encourages, serves, and directs our political reflection and consider how we can engage with its voice most responsibly and profitably.

❧ Most of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Susannah and Alastair

Susannah, this interview with a Jewish Christian, Wayne Weissman, might be of interest to you: https://hishill.org/captivate-podcast/interview-with-guest-speaker-and-his-hill-board-member-wayne-weissman/

Oh great, thank you very much. Now I'm going to be looking for counterfeit Exoduses everywhere in biblical tales of malefactors. :-)

9/11 for me coincided with a time of adult regeneration and a slow, long crawl to understand the God of the bible which I'm still working through. This recent atrocity seems to be an aftershock and I'm really glad how it has prompted me, along with many others apparently, to re-examine Christian-Jewish relations. I found James Wood's recent piece in Ad Fontes to be really helpful.

"All responsibility for lives lost in collateral damage supposedly belongs to Hamas and if, by comparison with Hamas, Israel is less indiscriminate and brutal in its methods, they must be the good guys"

This was one of my takeaways from watching Ben Shapiro's speech at the Oxford union. One doesn't have to adopt moral equivalency to be struck by the difficulty in the maneuver of claiming a mantle of absolute impeccability by dint of relative sin-superiority. I don't think it's a peculiarly Jewish way of looking at ethics, but rather a fallen, universal way. If there is a better example of works righteousness, I can't think of it. What a burden it must be.

For some reason or another my mind has been aflame also by what I am hearing in the rhetoric about anti-semitism and Zionism. It seems in the minds of many that the absolute legitimacy of the founding of the modern state of Israel is inextricably bound, and conflated, with the right of those people to defend themselves. When I hear this from Americans it troubles me, because it is contra the insights of the founders who recognized the universal right of self-defense as a gift from God, apart from the will of any state. So, God forbid, if the citizens of Israel were pushed out of the state, they cannot defend themselves?

This is where I think the Christian ethic of continual sojourn is superior. Rights come from God and the state must simply bow and exert its energies to defend those rights, not grant or establish them. Human rights are not handcuffed to a person's citizenhood in any way. Going the opposite direction, to me it seems, always seems to legitimate blood-and-soil religion and civics.