Dear friends,

I’m wearing seersucker and it’s after Labor Day: I apologize. I didn’t want to hide this from you, our readers. Shame is not always a bad thing. It can help us to become better people, and not wear seersucker after Labor Day.

On the other hand I just got a gel manicure for the first time, which has leveled up my power considerably. I had no idea.

I’m writing this on the Amtrak back from DC, where Alastair and I went for a conference and for the 10th anniversary celebration of the Davenant Institute. We met up with probably twenty friends we hadn’t seen in some cases since before COVID, including several who had known us separately before we were together: this is always a lot of fun. Also I got to cuddle many friends’ babies and we got to hang out with two of our favorite older children. (Cosette and Atticus, that’s you.)

Alastair: We are currently on a train, travelling back from a packed weekend in DC. Having travelled down to DC on a very hot and humid day by Megabus, we determined that we weren’t going to put ourselves through the unpleasant experience of such a bus journey so soon, so decided that we would return by train instead.

When last we posted, I was still in the UK and Susannah was in New York. Being back in the UK gave me the opportunity to enjoy a few weeks of a slower and more predictable routine, which I had been greatly missing. I spent some more time with my parents, going for a walk at Smith’s Pool in Fenton and other such things.

I also spent a morning with Tim Vasby-Burnie, walking near Oakamoor, a place I don’t recall visiting previously. Once again, I was reminded of how blessed we are with beautiful countryside in Stoke-on-Trent’s vicinity. We really need to make more of an effort to explore more of the surrounding region in the future, especially now that we have bikes. Just before returning to the US, I exchanged my bike with another bike from the neighbour from whom I originally bought it, as he now has back issues that made the other bike unsuitable for him. As I travelled down to London the day after, I have yet to cycle any distance on it, so am looking forward to that.

Stoke-on-Trent is, of course, famous for its eponymous potteries and for several years I have been building my own pottery collection, making the most of the sales and seconds in some of the potteries in our near neighbourhood. In Susannah’s absence, she wasn’t there to police me, so I picked up several new items in Portmeirion’s marquee sale. Although I only moved to Stoke in my later teens and have lived elsewhere for most of my adult life, I’ve always returned to Stoke and my collection of (chiefly) Portmeirion has represented something of my personal bond with and pride in the city. A few months ago, I picked up some heavily discounted seconds at Burleigh, which I brought over to New York in my check-in luggage. Fortunately, they made the journey intact. Whenever we eat from it, I now feel something of my bond with the Potteries.

The day before I flew back to New York, I preached at a wedding for the first time (yes, another wedding!). I had decided to preach on the connection between John 2 and Revelation 19. Besides these being readings for the wedding service, as my forthcoming Davenant course is on John and Revelation and as nuptial themes in the Johannine literature have been much on my mind of late (as you already know if you have been following this Substack) it seemed an apt topic.

The wedding was in St James Clerkenwell in London and was a glorious and happy occasion, with a superb choir, and followed by a reception in the Museum of the Order of St John, a beautiful and grand venue. The couple considerately placed me on the informally named ‘theology table’ for the reception, where much stimulating conversation was enjoyed.

My flight was delayed the next morning, which gave me the opportunity to attend Emmanuel Church in North London with my host, in their new building. Having visited them several times before, it was an unexpected blessing to be back there again.

Being back in the sweltering humidity of New York, I was soon pining for the generally mild and overcast weather I had left behind. Were it not for the existence of air conditioning, I doubt I would be able to survive long outside of the temperate climes of the UK. It was, however, wonderful to be reunited with Susannah after our longest period away from each other since we married.

Once again run down by lots of work, travel, and lack of sleep, I picked up a cold on my return to the US—my brain is still feeling rather dull and foggy. We didn’t have long in New York before we had to go down to DC, where I was speaking at a theology conference and we were attending a celebration of the Davenant Institute’s ten year anniversary.

Such trips are always intense yet delightful, affording us the opportunity to reconnect with many old friends, make several new ones, and to meet various people who appreciate our work. There are generally several new babies to meet and growing toddlers to see, which is always a source of entertainment and diversion, especially for Susannah! As so much of our work occurs in private settings—writing, researching, or recording in the solitude of our studies—and we have a relatively low profile in our primarily contexts, it is also humbling but profoundly encouraging to encounter people who tell us of the difference that our work has made for them.

We had some wonderful hosts, who had given us an open invitation to stay with them several months ago. Finally having the opportunity to take them up on their generous offer, we had a really refreshing stay.

Arriving on Thursday, we were able to take Friday to meet some online friends in person for the first time. We enjoyed a meal with a group at Bobby and Kristin Jamieson’s house and hung out with my Mere Fidelity colleague Matt Lee Anderson, who was one of the other speakers at the conference. The last time we met up with him was also in DC, back in January 2020, before we were together. On the Friday evening we attended a private reception for the conference.

The conference, hosted by the Church of the Resurrection, and sponsored by the Greystone Theological Institute, the Lydia Center, and the Institute of Religion and Democracy, was a great success, and will doubtless spark further conversation, collaborations, and endeavours. I gave the final talk of the day, on the rites of circumcision and baptism as they relate to a theology of flesh and bodies.

The celebration of the Davenant Institute’s tenth anniversary was later that evening. The work of Davenant has been such an essential part of both of our personal stories—also playing a crucial role in bringing us together—over the past decade. The anniversary celebration was a blessing, and a reminder of many past blessings. We both owe Davenant, the mission it has undertaken and the community it has developed and supported, an immense debt.

As I mentioned earlier, the journey down to DC on Megabus was pretty grim. Travelling back by train instead gave us a few more hours to enjoy with some friends—and with one of Susannah’s godsons—after church.

The Birth of Comedy

Susannah: Anyway. I wrote a thing. It’s long. It’s strange. It’s a trip. It’s about Nietzsche and Homer and Hesiod and Pindar and Bronze Age Pervert and contemporary neofascist vitalism and the emptiness at the heart of the post-Christian Right and Herakles and Odysseus and Orpheus and Eurydice and Hadestown and the Nephilim and Jesus. I really love it and I hope you’ll read it. Also it’s 13K words.

What did the Greeks hope for? What did they believe?

And what could that possibly have to do with us?

Circumcision and the Order of Bodies

In my talk yesterday (‘Redeeming the Flesh: The Conscription of the Body in the Story of Salvation’), I considered the significance of circumcision and baptism as they relate to the reality of our embodied physicality and sociality. In the Bible, the flesh and the body are not individualistic realities: we are bound together in solidarities of flesh and belong to social bodies. Furthermore, our flesh and our bodies are always already freighted with meaning, attachments, and history.

Our bodies have a priority: before I develop subjectivity, agency, or volition, I am a body. In my body I am related to the world and to other bodies. My body is both me and world, self and other. While we often equate the self with subjectivity, in the body the self also has an objectivity.

In Genesis the very name ‘Adam’ relates the first man to the earth—the adamah—from which he was fashioned: he is the earthling, the child of the earth. The connection between the human being and the earth is one to which we are recalled on several occasions in Scripture—“you are dust, and to dust you shall return.” Biblical poetry also expresses this bond in various places, especially in the association it draws between the womb and the earth: “Naked I came from my mother’s womb, and naked shall I return” or “My frame was not hidden from you, when I was being made in secret, intricately woven in the depths of the earth.”

The Bible speaks of the bond between a husband and a wife as a ‘one flesh’ union: in my very physical existence, I embody the union of my parents. Indeed, my body once found its home within and participated in the body of my mother and, even after birth, drew its sustenance from hers. Although I am a unique individual self, in ways mysterious both to them and to me, I also bear something of my parents’ legacy in my very DNA, recognizable in everything from aspects of my appearance to peculiarities of my personality.

There is a sort of grammar to the given reality of bodies. In modern societies that focus on and privilege individual selves and their autonomous self-defining choices, treating the order of bodies as existing downstream of these, it is easy to forget or resist the fundamental unchosen realities that lie at the origins of each one of us: male and female bodies and their asymmetric relations, conception, gestation, and birth. Such realities are inassimilable to many of the conceptual artifices that govern our societies.

The body’s objectivity, materiality, exteriority, and priority, and its embeddedness in the natural order, in a tradition, society, and culture are simultaneously preconditions for, yet also resistance to, the freedom of my subjectivity and action. The body constantly alerts us to the givenness of the self, to the fact that we are neither autonomous nor self-defined, but receive our identities—our being and our relational place in the world—chiefly from without. My freedom to ‘speak’ my own self necessarily presupposes that self has always already itself been ‘spoken’ and, having itself been spoken, also been spoken to. I must always express myself as an answer to the address of others from the unchosen site of identity and meaning that is my body.

The body has a character comparable to a Möbius strip, its interiority and exteriority continuous with rather than opposed to each other. Shame, for instance, can have a visceral bodily presence for us; we feel exposed and may even flush with embarrassment when the gaze of another rests upon us.

The Bible is attentive to bodies and the order of bodies in ways that can embarrass or offend modern sensibilities. It might shock us, for instance, that the ritual sign of the covenant made with Abraham was the cutting off of the foreskin of the penis. As we think of bodies chiefly as the means of individual agency and the realm of individual expression, a rite performed upon infants without any understanding or volition in the matter, and exclusively upon males, offends moral instincts that are so engrained for us that we have likely never questioned nor examined them. Such a rite suggests that bodies are not interchangeable avatars of individual persons, their particularities matters of indifference. They can be the bearers of natural—in this case, gendered—import and ordered to or implicated in other bodies. Identities can also meaningfully be borne by—and even ritually placed upon—the body of persons who did not choose them.

In circumcision, male bodies are singled out. However, women can be implicated in the circumcision (or lack thereof) of their male kin, as in the very strange story of Moses’ wife Zipporah and her emergency circumcision of their son (Exodus 4:24-26). Circumcision treats bodies in a manner that is alien to moderns: as exceeding individuality in their mutually implicatory character, as naturally meaningful, and as bearing given identities and unchosen duties. Circumcision accentuates the bodily givenness of the bonds between parents and their children, between males and females, and between persons and their bodies as sites of meaning which they must honour. Without some sense of the natural grammar of bodies, circumcision is incomprehensible.

As Howard Eilberg-Schwartz has observed, circumcision is a ‘fruitful cut’, symbolically fitting Abraham and his household to bear fruit for God. Circumcision (by analogy with ‘circumcised’ fruit trees (cf. Leviticus 19:23-25) is a symbolic ‘pruning’ of Abraham’s household, so that it might be like a domesticated vine of the Lord’s planting. Circumcision marks out the entire household of Abraham from their neighbours: it is not merely an external sign of private religious belief. In being performed upon the male sexual organ, it also heightens our alertness to and addresses that organ’s particular symbolic connotations. Circumcision is, among other things, a taming of phallic power: a domestication of unruly and violent male sexuality, a humbling of virile dominance, and the placing of fecundity within the bounds of covenant promise and law.

As moderns we have highly developed concerns for the dignity, moral equality, integrity, inviolability, individuality, and autonomy of persons, historically hard-won concerns that it would be foolish and dangerous for us to jettison. Nevertheless, such concerns must ultimately be grounded in and consistent with the natural order and grammar of bodies. Where they are not, they are always at risk of alienating ourselves from our own humanity, sundering the bonds between parents and children, diminishing the loving bond between the sexes by which the two halves of humanity are united and the species perpetuated, and estranging us from our own bodies. Reflecting upon the Abrahamic rite of circumcision is one way to alert us to the forgotten or neglected bodily substrate of all human society.

Recent Work

Susannah: Ok, it’s been a while since I did a roundup, but I’ll at least give you all a sampling.

❧ Following the publication of my Birth of Comedy piece, I was invited onto two different podcasts to discuss it. Brent Siddall interviewed me for the God’s Story Podcast and Aaron Irber discussed it with me on the I Might Believe in Faeries podcast.

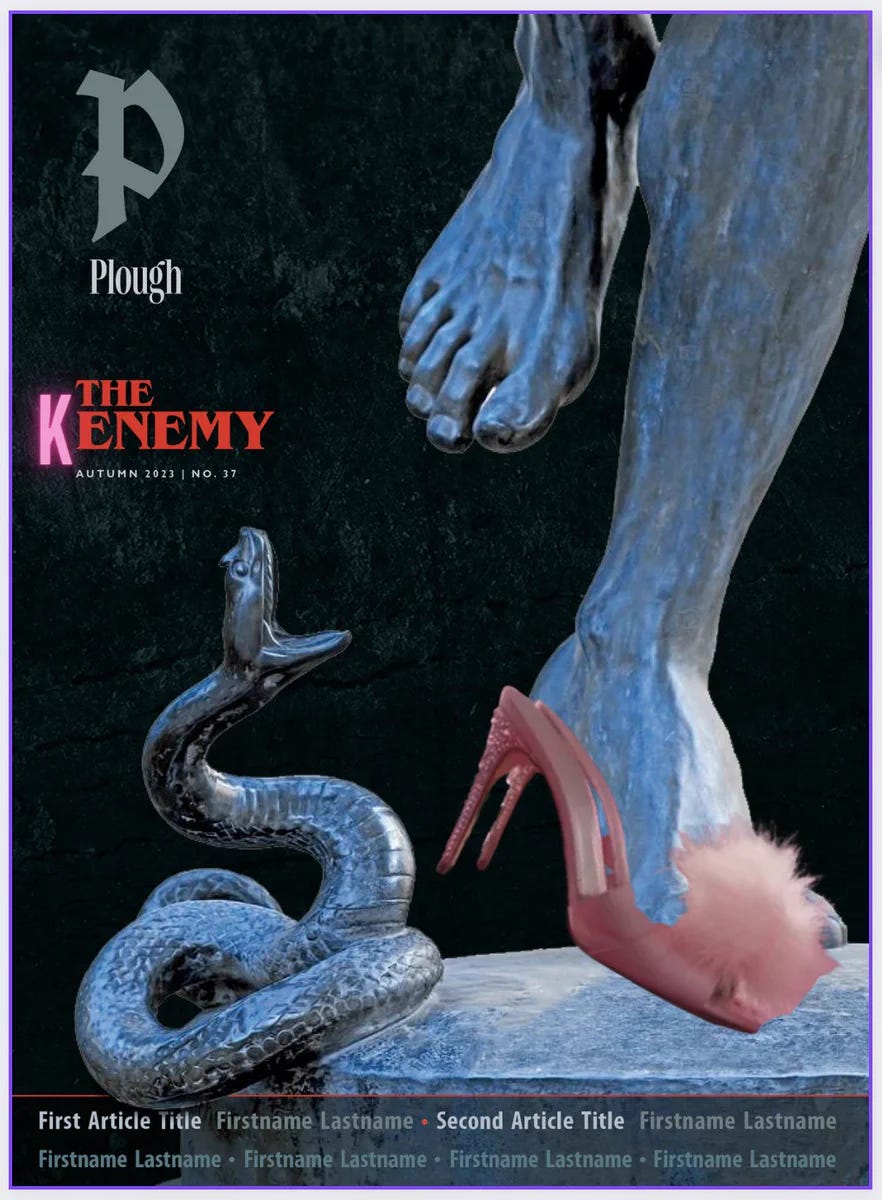

The latest issue of Plough is on the theme of The Enemy. We’ve got pieces on political enemies, how and why to love enemies, and, of course, on the Devil. There are a number of pieces in this I’d recommend.

❧ Ben Crosby, a friend who’s an Anglican pastor in Canada, writes about the political and ethical complications of loving one’s enemies, an idea that is unpopular on both left and right today - and calls us nevertheless to do so.

❧ Mary Townsend writes about how hatred works. Can you love the sinner and hate the sin? Does that even make sense?

❧ Timothy Kiederling writes an investigation of who specifically Jesus’ enemies were - those he called his followers to love.

❧ Leah Libresco writes about one of her jobs: being a “midwife to argument,” helping college students to fight well about the most fraught issues of our time.

❧ Sarah Clarkson writes about her experience of mental illness: what does it mean for one’s mind to be one’s enemy? How can one love the enemy that is one’s mind?

❧ Zena Hitz asks: What is time for? What is the use of leisure? And answers by looking to St. Augustine.

❧ For that issue, I wrote an obituary for Tim Keller, a Presbyterian pastor in New York. Tim was an inspiration: he refused to play the culture war game and instead focused on preaching the gospel, in a way that was accessible to New Yorkers.

We’ve also come out with a bundle of podcasts recently.

❧ I spoke with Phil Christman and Leah Libresco about effective altruism: is this an inhumane approach to charity, or a sensible one?

❧ Alastair and I talked about Mary of Bethany and the virtue of magnificence.

❧ Clare Coffey and Dan Walden were hilarious about the demented world of multilevel marketing.

❧ Is AI Demons? Paul Kingsnorth, Madoc Cairns, Alan Koppschall and I tackle the big questions.

❧ How does going back to the Greek to translate the New Testament, as David Bentley Hart has done, change how we understand Jesus’ teachings on money? DBH comes on the pod to answer. (NB I disagree with some of his takes but… look, that’s DBH. He was very charming.)

❧ Those were all pods related to our Money issue. The first Podcast linked to our Enemy issue has obviously got to be on Barbie. Was the movie a confused mess or deeply insightful? Hannah Long, Leah Libresco, Alastair and I say: Why not both?

Alastair: Besides the Barbie podcast, here are a few things I have produced since our last Substack post.

❧ Our latest Mere Fidelity episode was on Matthew Barrett’s latest book, The Reformation as Renewal: Retrieving the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church.

❧ Our Deuteronomy series on the Theopolis podcast continues with episodes on Deuteronomy 15: Biblical Slavery, Deuteronomy 16: Passover, the Feast of Weeks, and the Feast of Booths, and Deuteronomy 16: Justice and False Worship.

❧ I posted a video within which I gave a brief update and read a section from one of our recent Substack posts.

John and Revelation Course

The gospel of John stands out from the other gospels both in content and style. Reading it, you have probably had a sense of some of these differences. Perhaps the relative prominence of encounters with individuals, the importance of signs, the lack of parables, etc.

Familiar as we are with the other gospels, we might wonder why John chose to tell his story in such a distinctive way, framed differently from the other gospels, with different points of emphasis and different prominent themes. What was John intending to achieve?

At several points in reading John's gospel, you might also have been struck by a sense of déjà vu, a sense you've encountered certain scenes, words, or images before. You might wonder whether there is some allusion you could be catching, which might prove key to deeper meaning.

Perhaps you have also had a sense of a greater design in the structuring of the book. There are some episodes and scenes that seem to be juxtaposed with each other. Are there literary patterns and structures to be discovered?

Or maybe you've been enthralled by the profound and rich Trinitarian theology that seems to be implied in the text and want to plumb some of those depths. How might close attention to John's gospel inform our theology proper?

The book of Revelation is commonly claimed to have come from the same hand as John's gospel. What features of the books grant greater weight to this claim? Are there deeper connections to be observed? How might recognition of these enrich our reading of both books?

Revelation is dense with scriptural allusion (but not citations). How do we handle such allusions responsibly and how might they open up the meaning of difficult visions? What Old Testament background is most important for understanding Revelation?

Again, John presents the Triune God in complex and shifting imagery—the Lamb, the throne, the seven spirits, etc. How might such visionary imagery inform and be handled by our doctrine of God?

There seem to be several archetypal figures in the book of Revelation and lots of really weird symbolism. How does symbolism work in Scripture? How does Revelation relate to less symbolic books?

The end of Revelation recalls the very beginning of the Bible: a garden city, the bringing together of a man and a woman, water flowing out, God's presence in the midst, the tree of life, etc. How does Revelation function within the greater canon and serve as its capstone?

You might also have wondered about what events and time Revelation was predicting, how to weigh the claims of futurists, preterists, idealists, and historicists. What and when is the millennium? How does Revelation's eschatology relate to the rest of the New Testament?

All these issues and much more will be addressed in my forthcoming Davenant Hall course on John and Revelation. We will be exploring these challenging and rewarding texts in depth, in ways that might radically change how you read Scripture in the future.

Upcoming Events

❧ Next weekend I travel to Birmingham to teach a course on Exodus for Theopolis.

❧ Alastair’s Davenant Hall course on John and Revelation, which I have already mentioned, starts soon. If you are interested, you can register for the course here (registration closes on the 13th!).

❧ Most of Alastair’s work is as an independent scholar, funded by Patreon donors. His primary goal is to create thoughtful yet free Christian material for the general public, most notably his largely-completed chapter-by-chapter commentary on the whole Bible (available here and here). If you would like to support his continuing research, teaching, writing, and other content production, you can do so here.

Much love,

Susannah and Alastair

Reading your comments on the body, something struck me. For a long time I have taken the text "he learned obedience through what he suffered" and turned it over in my hand, trying to understand it. He suffered, of course, but how did he have to learn to obey? Being sinless? Well, his circumcision, for one. An act upon the body perpetrated not by himself, but on him by others. Yet, it was suffering, and also, it was obedience, by his parents, but to his credit. Brings to mind that often we learn to believe through the act of obedience before we fully believe.

It could be fun to compare and contrast circumcision, with the piercing of the ear with the awl to the door frame. Another type of fruitful bodily suffering.

Loved, loved, the essay. "They loved vitality because they had none".

The BAP atavists are saying "why were the former days better than these?" We know how that always turns out. They also don't seem to recognize the Hebrew shoulders their bronze age heroes are standing upon. Makes sense... if one doesn't recognize their Father, they won't really recognize any of their ancestors, either.

Fustel de Coulanges tells a story, I think about the battle of Arginusae, where an Athenian admiral was sentenced to death for not recovering the bodies of drowned sailors after the sea battle. The Athenians were furious and wanted a scapegoat, as they believed interring the dead sailors would protect the city. The admiral foreglimmered Christian ethics by opting to preserve his living sailors, as recovering the bodies in a brewing storm would have put them at mortal risk. I'm reminded of Christ saying "let the dead bury the dead". A teaching driving a stake into the heart of ancestor worship. None of us could really truly honor our mothers and fathers with that idolatrous conception running amuck in ancient society. Christ freed us from that bronze age perversion. And about a thousand other dark perversions.

If you ever get enough head of steam to write another 13k words, please delve into the comedy a bit more! Only a people who could be taught the true truth of what drinking blood means, could have produced Don Quixote.